Around 6a.m. on 8 October 1895,

Queen Min

Empress Myeongseong (; 17 November 1851 – 8 October 1895) was the official wife of Gojong, the 26th king of Joseon and the first emperor of the Korean Empire. During her lifetime, she was known by the name Queen Min (). After the founding o ...

, the consort of the Korean monarch

Gojong, was assassinated by a group of Japanese agents under

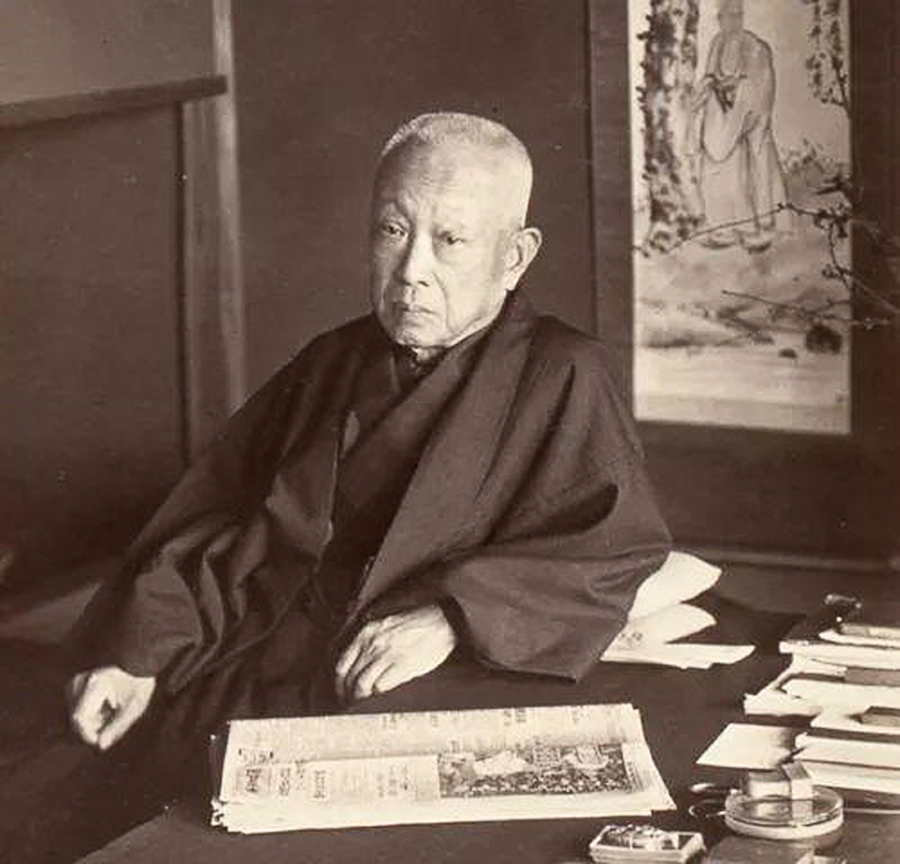

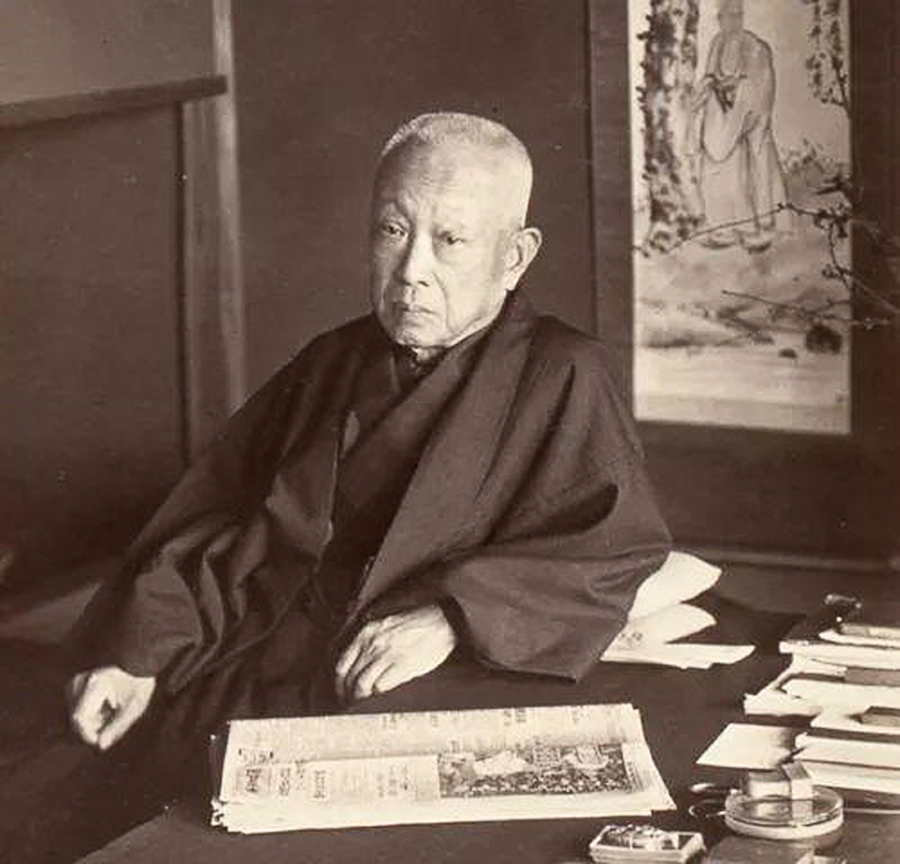

Miura Gorō

Viscount was a lieutenant general in the early Imperial Japanese Army; he is notable for orchestrating the murder of Queen Min of Korea in 1895.

Biography

Miura was born in Hagi in Chōshū Domain (modern Yamaguchi Prefecture), to a ''s ...

. After her death, she was posthumously given the title of "Empress Myeongseong". The attack happened at the royal palace

Gyeongbokgung

Gyeongbokgung () is a former royal palace in Seoul, South Korea. Established in 1395, it was the first royal palace of the Joseon dynasty, and is now one of the most significant tourist attractions in the country.

The palace was among the first ...

in

Seoul

Seoul, officially Seoul Special Metropolitan City, is the capital city, capital and largest city of South Korea. The broader Seoul Metropolitan Area, encompassing Seoul, Gyeonggi Province and Incheon, emerged as the world's List of cities b ...

,

Joseon

Joseon ( ; ; also romanized as ''Chosun''), officially Great Joseon (), was a dynastic kingdom of Korea that existed for 505 years. It was founded by Taejo of Joseon in July 1392 and replaced by the Korean Empire in October 1897. The kingdom w ...

. This incident is known in Korea as the Eulmi Incident.

By the time of her death, the queen had acquired arguably more political power than even her husband. Through this process, she made many enemies and escaped a number of assassination attempts. Among her opponents were the king's father the

Heungseon Daewongun

Heungseon Daewongun (; 24 January 1821 – 22 February 1898) was the title of Yi Ha-eung, the regent of Joseon during the minority of Emperor Gojong in the 1860s. Until his death, he was a key political figure of late Joseon Korea. He was also ca ...

, the pro-Japanese ministers of the court, and the Korean army regiment that had been trained by Japan: the

Hullyŏndae

The Hullyŏndae () was an infantry regiment of the Joseon Army (1881–1897), Joseon Army established under Empire of Japan, Japanese direction as a part of the second Gabo Reform in 1895, the 32nd year of Gojong of Korea's reign. On January 17 i ...

. Weeks before her death, Japan replaced their emissary to Korea with a new one: Miura Gorō. Miura was a former military man who professed to being inexperienced in diplomacy, and reportedly found dealing with the powerful queen frustrating. After the queen began to align Korea with the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

to offset Japanese influence, Miura struck a deal with

Adachi Kenzō

was a Japanese politician active during the Taishō and early Shōwa periods.

He participated in the 1895 assassination of the Korean queen.

Biography

Adachi was the son of a samurai in the service of the Hosokawa clan of Kumamoto Domain. Af ...

of the newspaper ''

Kanjō shinpō

in Shinto terminology indicates a propagation process through which a ''kami'', previously divided through a process called '' bunrei'', is invited to another location and there re-enshrined.

Evolution of the ''kanjō'' process

''Kanjō'' wa ...

'' and the Daewongun to carry out her killing.

The agents were let into the palace by pro-Japanese Korean guards. Once inside, they beat and threatened the

royal family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term papal family describes the family of a pope, while th ...

and the occupants of the palace during their search for the queen. Women were dragged by the hair and thrown down stairs, off verandas, and out of windows. Two women suspected of being the queen were killed. When the queen was eventually located, her killer jumped on her chest three times, then cleaved her head with a sword. Some assassins looted the palace, while others covered her corpse in oil and burned it.

The Japanese government arrested the assassins on charges of murder and conspiracy to commit murder. Non-Japanese witnesses were not called, and the court disregarded evidence from Japanese investigators, who had recommended that the assassins be found guilty. The defendants were acquitted of all charges, despite the court acknowledging that the defendants had conspired to commit murder. Miura went on to have a career in the Japanese government, where he eventually became Minister of Communications.

The killing and trial sparked domestic and international shock and outrage. Sentiment shifted against Japan in Korea;

the king fled for protection in the Russian legation and

anti-Japanese militias rose throughout the peninsula. While the attack harmed Japan's position in Korea in the short run, it did not prevent

Korea's eventual colonization in 1910.

Historiography

The assassination is highly contentious in Korea, where it is remembered as a symbol of

Japan's historical atrocities on the peninsula.

Information about the assassination comes from a variety of sources, including the memoirs of some of the assassins, the testimonies of foreigners who witnessed varying parts of the attack,

the testimonies of Korean eyewitnesses, investigations conducted by Japanese emissaries

Uchida Sadatsuchi and

Komura Jūtarō, and the verdicts of the trials of the assassins in Hiroshima. Evidence for the assassination is written in at least four languages: English, Korean, Japanese, and Russian.

For over a century now, scholars from various countries have analyzed varying portions of the body of evidence and have reached differing conclusions on significant issues.

Evidence has continued to emerge even into the 21st century, which contributes to ongoing debate.

Background

Since

its forced opening by Japan in 1876, Korea had been subjected to a number of great powers competing for influence over it. Powers included the

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

,

Qing China

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the Ming dynasty ...

, the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, and the United States. The strength of each of these powers in Korea changed frequently. Within the Korean government, various politicians, departments, and military units acted according to independent interests and alignments.

One prominent faction was led by the father of King

Gojong: the

Heungseon Daewongun

Heungseon Daewongun (; 24 January 1821 – 22 February 1898) was the title of Yi Ha-eung, the regent of Joseon during the minority of Emperor Gojong in the 1860s. Until his death, he was a key political figure of late Joseon Korea. He was also ca ...

. The Daewongun, wanting a submissive and obedient wife for Gojong, selected an orphan of the prestigious

Yeoheung Min clan

The Yeoheung Min clan () is a Korean clan that traces its origin to Yeoju, Gyeonggi Province. The 2015 Korean census counted 167,124 members of the Yeoheung Min clan.

Origin

The progenitor of the Yeoheung Min clan was long thought to be Min C ...

for the role, and she became Queen Min. She was widely agreed to be politically savvy and sharp, and she began consolidating power. According to observers, she came to wield even more political power than her husband. The queen forced the Daewongun into retirement, and replaced his allies with her own. The Daewongun and queen developed a fierce rivalry. Her gender also played a role in how she was perceived; in both Japan and Korea at that time, women were expected to be relatively secluded and it was uncommon for them to hold significant political power.

The combination of these factors made her the target of retaliation. Both the Daewongun and the Japanese became involved in efforts to suppress her power. Assassination attempts were made against her in the 1882

Imo Incident

The Imo Incident, also sometimes known as the Imo Mutiny, Soldier's riot or Jingo-gunran in Japanese, was a violent uprising and riot in Seoul beginning in 1882, by soldiers of the Joseon Army who were later joined by disaffected members of the ...

and 1884

Gapsin Coup

The Kapsin Coup, also known as the Kapsin Revolution, was a failed three-day coup d'état that occurred in Korea during 1884. Korean reformers in the Enlightenment Party sought to initiate rapid changes within the country, including eliminating ...

. In 1894, the Daewongun struck a deal with Japanese military leader

Ōtori Keisuke

Baron was a Japanese military leader and diplomat.Perez, Louis G. (2013)"Ōtori Keisuke"in ''Japan at War: An Encyclopedia,'' p. 304.

Biography

Early life and education

Ōtori Keisuke was born in Akamatsu Village, in the Akō domain of Harim ...

to purge the queen and her allies, but the plot failed, and the queen regained her influence.

''Sōshi'' and the ''Kanjō shinpō''

Beginning around the 1860s, groups of young men called ' () emerged in Japan and engaged in political violence. They were seen in Japan as violent thugs and looked down upon. They were the product of groups such as the

''shishi'' and rebel

Satsuma Army. Beginning in the 1880s, a number of them moved to Korea. In Korea, they had the right of

extraterritoriality

In international law, extraterritoriality or exterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdict ...

and were thus unbound by Korean law. They, in nationalist groups such as and

Kokuryūkai, acted with impunity especially in the countryside.

A number of the ''sōshi'' became journalists, and became associated with various Japanese newspapers in Korea, namely the ''

Kanjō shinpō

in Shinto terminology indicates a propagation process through which a ''kami'', previously divided through a process called '' bunrei'', is invited to another location and there re-enshrined.

Evolution of the ''kanjō'' process

''Kanjō'' wa ...

''. This newspaper and its employees later became central to the assassination plot.

Instability and the Hullyŏndae

Around 1894, Korea suffered from significant internal instability. The

Donghak Peasant Revolution

The Donghak Peasant Revolution () was a peasant revolt that took place between 11 January 1894 and 25 December 1895 in Korea. The peasants were primarily followers of Donghak, a Neo-Confucian movement that rejected Western technology and i ...

and

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 189417 April 1895), or the First China–Japan War, was a conflict between the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan primarily over influence in Joseon, Korea. In Chinese it is commonly known as th ...

for control over Korea concurrently took place on the peninsula. Around this time, the Japanese trained their own battalions of Koreans on the peninsula: the

Hullyŏndae

The Hullyŏndae () was an infantry regiment of the Joseon Army (1881–1897), Joseon Army established under Empire of Japan, Japanese direction as a part of the second Gabo Reform in 1895, the 32nd year of Gojong of Korea's reign. On January 17 i ...

. Much of the Hullyŏndae were loyal to Japan, and developed a strained relationship with the other Korean security forces. This led to a number of violent clashes between them.

Developing the plot

''Sōshi'' advocacy for the assassination

The ''sōshi'' became fixated on the politically-active Korean queen. According to historian Danny Orbach, a mix of sexism, racism, and political agendas led to members of the ''Kanjō shinpō'' taking the lead in plotting her assassination. They began to romanticize her killing; in his memoirs, founder of the ''Kanjō shinpō''

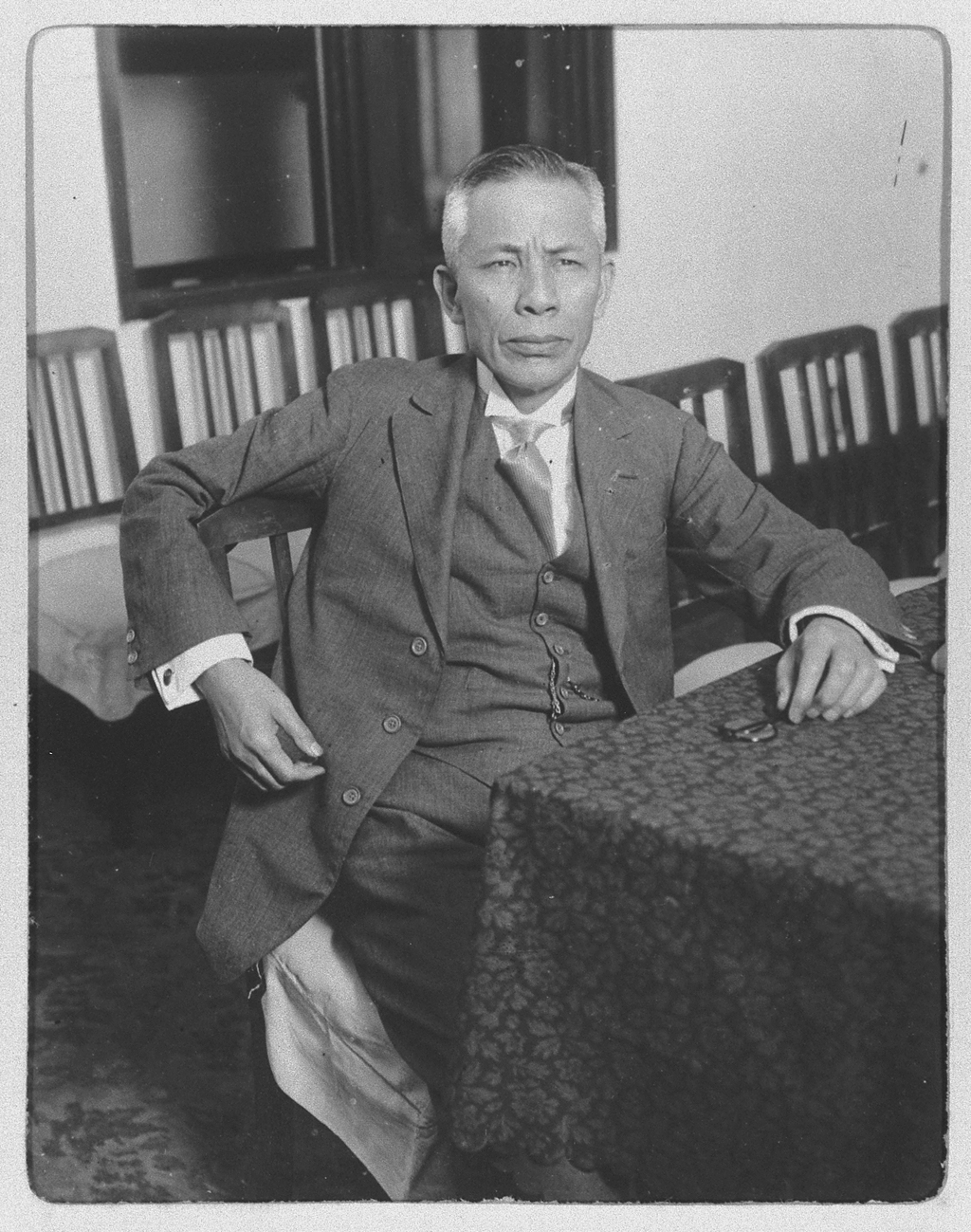

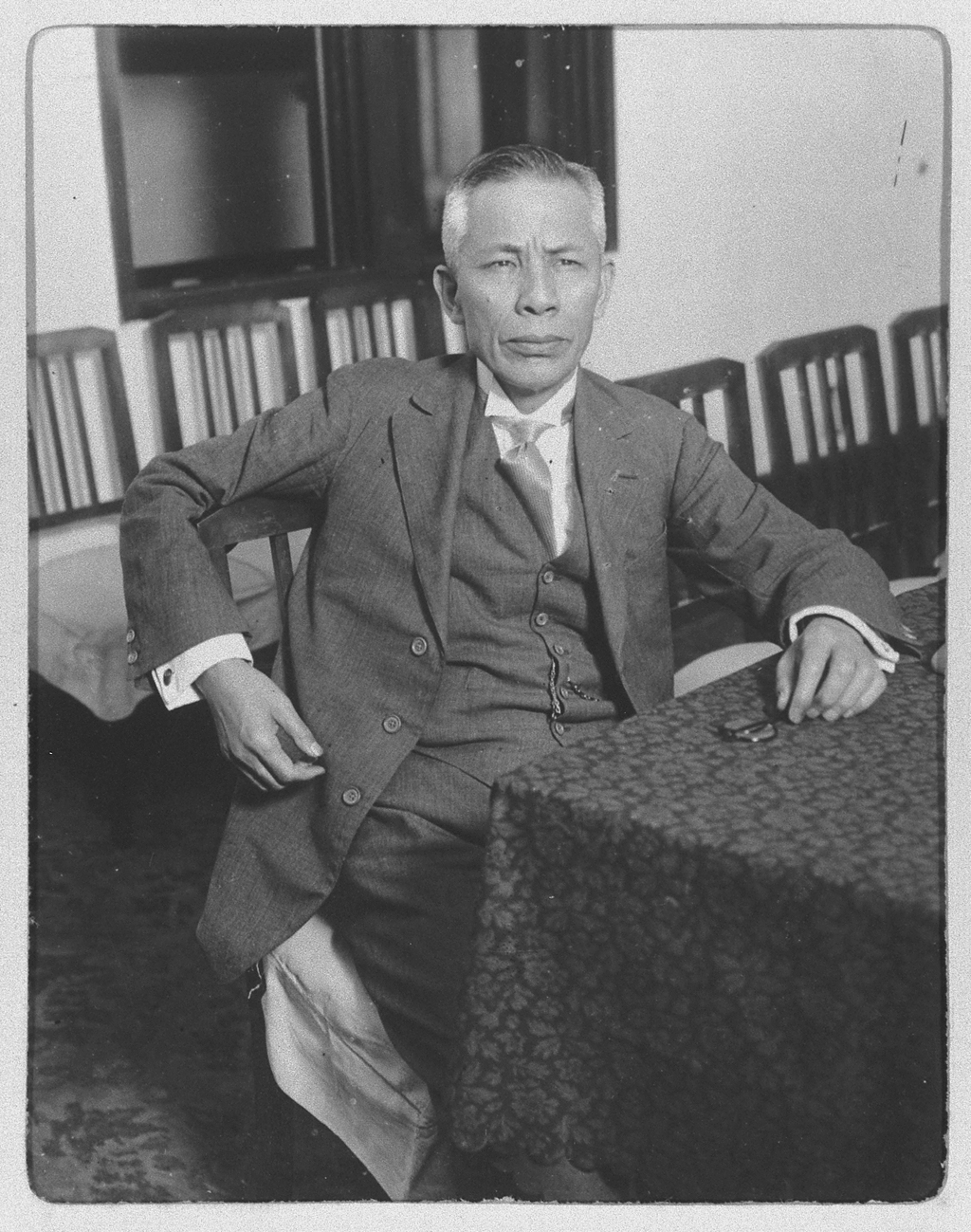

Adachi Kenzō

was a Japanese politician active during the Taishō and early Shōwa periods.

He participated in the 1895 assassination of the Korean queen.

Biography

Adachi was the son of a samurai in the service of the Hosokawa clan of Kumamoto Domain. Af ...

described the queen as "that bewitching beauty, who cunningly, ubiquitously, and treacherously manipulated virtuous men for over a generation". They romanticized the male Daewongun as "the old hero", and juxtaposed him to the image of an evil feminine queen. Adachi and others at the ''Kanjō shinpō'' referred to her in writings as a "fox" or "vixen", and began frequently commenting to each other that she should be killed, which they described as ''hōru'' (; ). Calls for her killing reportedly increased over time.

Miura Gorō

In summer of 1895, the Japanese government replaced its envoy in Korea

Inoue Kaoru

Marquess Inoue Kaoru (井上 馨, January 16, 1836 – September 1, 1915) was a Japanese politician and a prominent member of the Meiji oligarchy during the Meiji period of the Empire of Japan. As one of the senior statesmen ('' Genrō'') in ...

with Miura Gorō. Miura had previously been a soldier and military commander, and he privately professed to loathing politics and politicians.

A number of scholars have argued that the reason for Miura's appointment is uncertain. He professed to having little interest or experience in diplomacy, and the post was difficult and important to Japan.

He refused the post thrice, and by his own admission thought it complicated and confusing. He felt as though he was being pushed to Korea, and reluctantly accepted the position.

When he arrived there, he wrote that he found the queen to be intelligent and condescending to him. Orbach wrote that Miura "felt clueless and helpless" in dealing with her, and that Japan was in fact in a position of weakness in Korea due to Miura's poor performance in his role. Scholars have reasoned that, as a soldier, Miura was aggressive by nature, and therefore chose to act violently.

According to Orbach's analysis, Miura privately despised his superiors, and acted despite their wishes. Miura later wrote of his role in the plot:

Japanese government involvement in the assassination

There is disagreement as to whether the mainstream Japanese government had any role in planning the assassination.

The South Korean ''

Encyclopedia of Korean Culture

The ''Encyclopedia of Korean Culture'' () is a Korean-language encyclopedia published by the Academy of Korean Studies and DongBang Media Co. It was originally published as physical books from 1991 to 2001. There is now an online version of the ...

'', which has been described as one of the most frequently-used encyclopedias for

Korean studies

Korean studies is an academic discipline that focuses on the study of Korea, which includes South Korea, North Korea, and diasporic Korean populations. Areas commonly included under this rubric include Korean history, Korean culture, Korea ...

, has an article on this incident that claims that denial of the Japanese government's involvement mainly comes from historians of Japan.

It further argues that the Japanese government had the incentive to kill the queen, as she was significantly damaging Japan's position in Korea. It points out the odd choice of the inexperienced and militant Miura as the new emissary, and notes that Miura visited Japan for some reason on 21 September, several weeks before the assassination. Miura's visit reportedly led to rumors in Seoul that the queen would be assassinated. Also, the article argues that the broad involvement of the Japanese consular police and military in the plot makes the isolation of the plot implausible.

According to Orbach, a historian of Japan and other places, Inoue and his superiors in Japan were hesitant about assassinating the queen. Orbach provided the reasoning that Inoue had previously offered the queen Japan's protection if she ever felt that she was in danger. British explorer

Isabella Bird

Isabella Lucy Bishop (; 15 October 1831 – 7 October 1904) was an English explorer, writer, photographer and naturalist. Alongside fellow Englishwoman Fanny Jane Butler, she founded the John Bishop Memorial Hospital in Srinagar in modern-da ...

, who was in Korea around this time, wrote of this assurance:

Creating the plan

Around 19 September 1895, Miura met with Adachi. According to Adachi's testimony, Miura euphemistically asked Adachi if he knew of any young men available for a "fox hunt" (), and Adachi enthusiastically agreed. He wrote that "his heart leaped with joy" when Miura shared his plan. Adachi cautioned that the ''Kanjō shinpō'' staff were gentle by nature, and that he wanted to recruit others for the plot. Miura rejected this, and asked that Adachi use all of his employees in the interest of secrecy. Adachi recruited all of the ''Kanjō shinpō'' staff for the task, and a group of other ''sōshi''.

The men were reportedly greatly excited about the coming attack. Journalist Kobayakawa Hideo reportedly almost burst into tears when he was initially told to stay behind, and later claimed that he felt like he was among "heroes of a novel" during the assassination. reportedly told Adachi's wife that she "must be sorry

he wasborn a woman", because she could not join the assassins.

According to the verdict of the preliminary court in Hiroshima, the plan was formally approved in a meeting at the Japanese Legation on 3 October in a meeting between Miura, , and .

The Daewongun's role in the plot

There is disagreement as to what kind of role the Daewongun had in the plot.

According to historians of Japan Orbach and

Donald Keene

Donald Lawrence Keene (June 18, 1922 – February 24, 2019) was an American-born Japanese scholar, historian, teacher, writer and translator of Japanese literature. Keene was University Professor emeritus and Shincho Professor Emeritus of Japane ...

, on 5 October, Okamoto met with the Daewongun and implied that an uprising was imminent. Okamoto offered the Daewongun a series of conditions in exchange for power. How the Daewongun responded is not known; one man later testified during his trial that the Daewongun happily accepted the conditions. Okamoto testified that the Daewongun initially rejected them, but eventually relented.

The ''Encyclopedia of Korean Culture'' does not mention whether this meeting took place, and claims that, overall, the Daewongun did not participate in this plot willingly.

Accelerating the timeline

They originally planned to execute the murder in mid-October, but officers of the Hullyŏndae, especially the Korean commander of the Second Battalion , warned the plotters that the queen was about to take action against them. On the 7th, the Korean war minister advised Miura that the court had ordered the disbandment of the Hullyŏndae. As the war minister had no authority to disband it, he asked Miura to do it. In reply to this request, Miura reportedly angrily yelled, "You fool, never!" and forced him out of the room.

Miura felt that they needed to act quickly, as the Hullyŏndae was critical to their plot. He felt that the queen was going to assassinate pro-Japanese Korean politicians to align Korea with Russia. They decided to kill her on the next day, 8 October.

According to Orbach, Inoue Kaoru reportedly made a final attempt to stop the assassination. Inoue telegraphed Miura and asked him to visit the palace and negotiate a peaceful solution. Sugimura and Miura reportedly gave an evasive reply, writing, "

rnings will not be effective. The situation is very dangerous, and it is difficult to know when an incident will occur".

Assassination

Convincing the Daewongun

According to Orbach and Keene, in the early hours of 8 October, Okamoto, Deputy Consul , Police Inspector

Ogiwara Hidejiro (), and an armed group of men in civilian clothing went to the Daewongun's residence at Gongdeok-ri. They arrived around 2 am, and the leaders went inside to speak with the Daewongun. The negotiations took several hours, and the Japanese negotiators grew impatient. They potentially employed force in getting the Daewongun to agree or move quicker. They boarded him onto a

litter

Litter consists of waste products that have been discarded incorrectly, without consent, at an unsuitable location. The waste is objects, often man-made, such as aluminum cans, paper cups, food wrappers, cardboard boxes or plastic bottles, but ...

, and began carrying him to the palace. On the way, the Daewongun stopped the men and asked to receive their word that the king and crown prince would not be harmed. They were joined by around sixty men on the way. Among those men were around thirty ''sōshi'', Korean civilians, Hullyŏndae, Japanese army officers, and consular policemen.

The ''Encyclopedia of Korean Culture'' writes that the Daewongun and

his son were kidnapped () at this meeting and taken to the palace.

Securing the palace

According to Orbach, Korean collaborators neutralized the palace guards (''siwidae''). Soldiers were quietly reassigned from their posts or convinced to allow the plot. No guards were stationed on the path to the queen.

Around 5 am,

as the sun was beginning to break, some of the Japanese policemen climbed the walls of the palace using folding ladders and opened the gates from the inside. The northwest gate () and northeast gate () were opened first, then the main south

Gwanghwamun

Gwanghwamun () is the main and south gate of the palace Gyeongbokgung, in Jongno District, Seoul, South Korea. It is located at a three-way intersection at the northern end of Sejongno. As a landmark and symbol of Seoul's history as the capita ...

and north gate

Sinmumun

Sinmumun () is the north gate of the palace Gyeongbokgung in Seoul, South Korea. It was used generally by military personnel.

It was built in 1433. Sejong the Great

Sejong (; 15 May 1397 – 8 April 1450), commonly known as Sejong the G ...

followed.

According to the ''Encyclopedia of Korean Culture'', around 300 to 400 guards were stationed at the palace.

Limited gun fights occurred, and the palace guard abandoned their posts for their own safety. A Korean Hullyŏndae commander loyal to the queen,

Hong Kyehun, confronted the attackers. He was shot to death by a Japanese officer. According to ''sōshi'' Kobayakawa, the road became littered with abandoned caps, weapons, and uniforms. The American military advisor to Korea

William McDye attempted to rally several dozen troops to fight, but they disobeyed.

Around 5 am, the collaborating Korean Vice Minister of Agriculture advised the queen to stay put for her own safety, and that the Japanese would not harm her. Gojong awoke and became alarmed by the noise outside. He dispatched a confidant to alert the American and Russian envoys. The assassins surrounded the inner chamber of the palace and blocked all exits.

Searching for the queen

According to historian of Korea

Sheila Miyoshi Jager

Sheila Miyoshi Jager (born 1963) is an American historian. She is a Professor of East Asian Studies at Oberlin College, author of two books on Korea, co-editor of a third book on Asian nations in the post-Cold War era, and a forthcoming book on g ...

, neither Miura nor any of the agents knew what the queen looked like, as they had never seen her before. Jager wrote that Miura testified that a screen had always been erected between the queen and outside visitors. They had heard the queen had a bald spot above her temple. According to the ''Encyclopedia of Korean Culture'', British diplomat

Walter Hillier

Sir Walter Caine Hillier KCMG CB (1849 – 9 November 1927) was a British diplomat, academic, author, Sinologist and Professor of Chinese at King's College London.

Early life

Walter Hillier was born in Hong Kong but educated in England, at ...

testified that the assassins had a photo of the queen.

The assassins needed to search for and deduce who the queen was. According to ''sōshi'' Takahashi Genji, the two main ''sōshi'' factions there, the Freedom Party and Kumamoto Party, had a bet running on who could find the queen first. Orbach reasoned that this probably contributed to the eventual brutality of her killing.

The assassins began frantically searching for the queen, beating the people in the palace for information, and dragging everyone outside of the inner hall. Women were beaten and dragged by the hair and thrown out of windows and off verandas, with some falling around two meters (around 7 feet) onto the ground. Russian advisor

Afanasy Seredin-Sabatin

Afanasii Ivanovich Seredin-Sabatin (Афанасий Иванович Середин-Сабатин) was a Russian steersman-pilot and reporter for an English newspaper, but is best known as the first European (Russian) architect to live and work ...

feared for his life, and asked to be spared by the Japanese. He witnessed Korean women being dragged by the hair and into the mud. According to the official Korean investigation report:

Two court ladies were suspected of being the queen; they were both slashed to death. The Minister of the Royal Household Yi Kyŏngjik () moved to block the ladies' quarters, where the queen was. His hands were sliced off, and he bled to death. The crown princess was thrown down the stairs, and the crown prince was similarly threatened.

Killing of the queen

It is not known who killed the queen. Several people boasted of the achievement, with Keene evaluating some testimonies as unconvincing. It was possibly ''sōshi''

Takahashi Genji (alias Terasaki Yasukichi) or a Japanese army lieutenant.

Takahashi later testified:

According to the testimony of the Korean

crown prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title, crown princess, is held by a woman who is heir apparent or is married to the heir apparent.

''Crown prince ...

, the killer threw her to the floor, jumped on her chest three times, and slashed her with his sword.

It wasn't yet clear to them that they had killed the queen, so they brought a number of women over to examine the body. The women mourned and collapsed in anguish at the sight of her, which the assassins took as confirmation. They then took the body of the queen into a nearby forest, poured gasoline over her, and set her on fire.

Immediate aftermath

The agents looted the palace

and left through the palace's main gate

Gwanghwamun

Gwanghwamun () is the main and south gate of the palace Gyeongbokgung, in Jongno District, Seoul, South Korea. It is located at a three-way intersection at the northern end of Sejongno. As a landmark and symbol of Seoul's history as the capita ...

. They left the palace gradually, and were witnessed by foreign envoys leaving even by 7 am.

People came to investigate the commotion. Editors of the journal ''

The Korean Repository'' wrote that they saw that Gyeongbokgung's front gate was being guarded by Japanese troops, and that a surging crowd of Koreans was inside, with palace women notably among them. An American envoy and Russian colleague wrote of "Japanese with disordered clothes, long swords and sword canes" hurrying around.

Around 6 am,

Miura and the Daewongun then went to the palace. According to Miura, the Daewongun was "beaming with delight". The two went to a separate building to have an audience with Gojong, who was deeply shaken by the attack. The Daewongun gave Gojong a number of documents to sign. In one, he vowed to aid Gojong in expelling "low fellows", saving the country, and establishing peace. A proclamation read:

Gojong reportedly responded to the Daewongun with "you can cut my fingers off, but I will not sign your proclamation". The Daewongun was forced to issue the edict without the royal

seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, also called "true seal"

** Fur seal

** Eared seal

* Seal ( ...

, and published it in the ''Official Gazette''. He received only one endorsement from a minister of his new pro-Japanese cabinet. It was widely rejected by foreign diplomats in Seoul.

Distrust in the palace

The Daewongun and new cabinet pushed for influence in the palace. King Gojong asked foreigners to stay with him, to serve as witnesses to deter further Japanese attacks. The foreigners prevented both Korean and Japanese people from seeing the king or crown prince out of caution.

A loyalist group made an attempt to extract Gojong from the palace. However, one of the plotters who was to open the gate informed the Daewongun of the plot.

Gojong initially suspected the attack to not be of Miura's doing, but to be the initiative of Okamoto and his pro-Japanese advisors:

Kim Hong-jip

Kim Hong-jip (; 1842 – February 11, 1896) was a Korean politician best known for his role as prime minister during the Kabo Reform period from 1895–1896. His name was originally Kim Goeng-jip () which he later changed to Kim Hong-jip ...

,

Yu Kil-chun

Yu Kil-chun (; November 21, 1856 – September 30, 1914) was a Korean politician. Yu lived during the last few decades of Joseon and the Korean Empire, before the occupation of the peninsula by Japan. As a young man, he studied the Chinese cl ...

, Cho Ŭiyŏn, and Chŏng Pyŏngha ().

Miura's response

Numerous witnesses had seen the movement and identity of the attackers, which Orbach argues made a trail back to Miura. Korean royal emissaries rushed over to the Japanese legation to summon Miura. They found Miura and Sugimura already dressed and prepared to go, with a

litter

Litter consists of waste products that have been discarded incorrectly, without consent, at an unsuitable location. The waste is objects, often man-made, such as aluminum cans, paper cups, food wrappers, cardboard boxes or plastic bottles, but ...

prepared for the walk.

Responding to foreign witnesses

In the afternoon on the 8th, Miura was confronted with accusations from other envoys, especially those of Russia and America. Miura claimed that it was not known what had happened to the queen and that she had possibly escaped,

and placed the blame of the incident on the Daewongun and the Hullyŏndae.

The Russian envoy,

Karl Ivanovich Weber

Karl Ivanovich Weber (also Carl von Waeber; , , Liepāja – 8 January 1910) was a diplomat of the Russian Empire and a personal friend to King Gojong of Korea's Joseon Dynasty. He is best known for his 1885–1897 service as Russia's first cons ...

, insisted that Japanese swords had been seen at the crime scene. Miura responded by claiming they were probably the swords of Koreans pretending to be Japanese. On the morning of the 9th, Miura arranged for the new pro-Japanese war minister to claim that Korean rebels had dressed up in Japanese clothes. For this, three Korean scapegoats were executed.

News of the assassination spread slowly. Witnesses McDye and Sabatin shared what they had seen with the foreigner community in Seoul. American journalist

John Albert Cockerill, who wrote for the ''New York Herald'' and happened to be in Seoul at the time, attempted to telegraph news of the killing. However, Miura pressured the telegraph office into not sending the message. On the 14th, the United States finally learned of what had happened. When it asked the Japanese legation to confirm, the legation responded that the attack was purely led by the Daewongun and Hullyŏndae, and that it was not known if the queen had been killed.

Miura was widely disbelieved. A few days afterwards, the Russian and American legations sent marines to protect the king.

Japanese investigation

At 8 a.m. on the 9th, Miura telegraphed Japanese acting foreign minister

Saionji Kinmochi

Kazoku, Prince was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan, prime minister of Japan from 1906 to 1908, and from 1911 to 1912. As the last surviving member of the ''genrō'', the group of senior statesmen who had directed pol ...

with the assurance that the commotion was merely infighting between Korean troops. He told Saionji that it was unknown if the queen was still alive. Saionji asked Miura if any Japanese people had been involved. Miura replied that the queen "might have been" killed, but that Japanese involvement was still uncertain. That evening, he told Saionji that "some Japanese" may have been involved in the incident, but "did not do violence". Miura placed the blame of the incident on the queen, and reportedly hinted that she needed to have been prevented from disbanding the Hullyŏndae and decreasing Japanese influence in Korea.

Fearing a confrontation between the foreign marines and the Japanese forces, Saionji ordered Miura to restrain the ''sōshi'' and to keep the Japanese soldiers in their barracks. The home minister also requested that Prime Minister

Itō Hirobumi

Kazoku, Prince , born , was a Japanese statesman who served as the first prime minister of Japan from 1885 to 1888, and later from 1892 to 1896, in 1898, and from 1900 to 1901. He was a leading member of the ''genrō'', a group of senior state ...

issue an edict banning additional ''sōshi'' from traveling to Korea.

Japanese Consul

Uchida Sadatsuchi, supreme Japanese judicial authority in Seoul, was reportedly enraged by Miura's conduct. He wrote that Miura had treated everyone but the plotters, including others in the Japanese government, as outsiders. Uchida initially considered whitewashing the whole affair, especially as he was still unsure as to whether Japanese people had been involved, but ultimately began his own investigation. Diplomat

Komura Jūtarō was dispatched from Tokyo to investigate the murder. The two concluded that Miura and the others had actually orchestrated the murder, and submitted a candid report to Tokyo on 15 November, with a recommendation that the plotters be punished. Uchida also expelled some of the ''sōshi'' from Korea, which caused him to receive violent threats from parts of the Japanese settler community.

Japanese trial and acquittal

On 17 or 18 October,

the Japanese recalled Miura, Sugimura, Okamoto, and the ''sōshi'' to Japan for trial. After partaking in farewell banquets where they were hailed as national heroes by the Japanese settlers, they boarded a ship to Hiroshima, with some of them reportedly hopeful that they would again be welcomed as heroes. Upon their arrival, they were arrested on charges of murder and conspiracy to commit murder.

Civilian trial

According to Orbach, the trial report is "surprisingly honest" up until the Japanese entry to the palace. It portrayed Miura as having a clear intention to kill the queen. However, the record abruptly ends there.

On 20 January 1896,

the defendants were acquitted of all charges on the grounds of insufficient evidence. This included the charge of conspiracy to commit murder. The verdict cited Article 165 of the Meiji Code of Criminal Procedure (), which gave judges the authority to acquit if they believed evidence was insufficient. Evidence gathered for the trial was also returned to all original owners.

According to Danny Orbach:

The general consensus among recent historians is that the Japanese government likely intervened in the trial. In 2005, a professor at

Seoul National University

Seoul National University (SNU; ) is a public university, public research university in Seoul, South Korea. It is one of the SKY (universities), SKY universities and a part of the Flagship Korean National Universities.

The university's main c ...

discovered a document that reportedly confirmed that

Emperor Meiji

, posthumously honored as , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the List of emperors of Japan, traditional order of succession, reigning from 1867 until his death in 1912. His reign is associated with the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which ...

had received Uchida's report on the assassination around nine days before the trial. Orbach expresses skepticism of this intervention, and argued that there is no direct written proof of the intervention of the emperor or the government, and that if the government intervened it was likely in great secrecy. Orbach also notes that the acquittal was possibly the sole decision of Judge Yoshioka Yoshihide ().

Military trial

Shortly before the civilians were acquitted, the military tribunal of the Hiroshima Fifth Division acquitted all the military personnel involved in the assassination. According to Orbach, the tribunal initially seemed to believe in their innocence, but gradually began to notice significant contradictions in the testimonies. The tribunal asked for the army ministry to send investigators to interrogate military personnel stationed in Korea. However, ultimately the investigators expressed sympathy for what would happen to the defendants and their families if the defendants were to be found guilty. The tribunal reasoned that they were

just following orders, and that Japanese martial law was unclear as to whether subordinates had the right to disobey unjust orders.

After a final consultation with the Japanese government's Army Ministry, the tribunal decided to acquit the defendants. The tribunal ruled that the defendants did not know there was a plot to kill the queen, and that they were only guarding the gates and helping the Daewongun enter the palace.

Fates of the assassins

Most of the assassins returned to Korea and resumed their careers, where they became key voices of the Japanese community there. Adachi remained as president of the ''Kanjō shinpō'' and stayed in Japan to enter parliamentary politics. He eventually became Minister of Communications.

Impact

Increased Russian influence in Korea

On 11 February 1896,

Gojong and the crown prince fled to the Russian legation for safety. Gojong ordered the executions of four of his pro-Japanese cabinet, whom he dubbed the Four Eulmi Traitors. This ended the

Kabo Reform

The Kabo Reform () describes a series of sweeping reforms suggested to the government of Korea, beginning in 1894 and ending in 1896 during the reign of Gojong of Korea in response to the Donghak Peasant Revolution. Historians debate the degree ...

.

Gojong disbanded the Hullyŏndae for participating in the assassination and Capital Guards for failing to stop the Japanese. Until Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War, Japan's position in Korea was significantly weakened by the assassination.

International response

Japan initially received some international backlash for the murder.

However, the backlash was shortlived, with foreign governments determining that forwarding their foreign policy interests in Asia was more important than escalating the issue with the Japanese.

Anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea

The Korean public was outraged when they learned of the assassination. The pro-Japanese Prime Minister

Kim Hong-jip

Kim Hong-jip (; 1842 – February 11, 1896) was a Korean politician best known for his role as prime minister during the Kabo Reform period from 1895–1896. His name was originally Kim Goeng-jip () which he later changed to Kim Hong-jip ...

was confronted by a mob and lynched. Several months later,

Kim Ku

Kim Ku (; August 29, 1876 – June 26, 1949), also known by his art name Paekpŏm, was a Korean independence activist and statesman. He was a leader of the Korean independence movement against the Empire of Japan, head of the Provisional Gove ...

, who later served as the president of the

Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea

The Korean Provisional Government (KPG), formally the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea (), was a Korean government-in-exile based in Republic of China (1912–1949), China during Korea under Japanese rule, Japanese rule over K ...

, assassinated a Japanese man as revenge for the queen's murder.

In 1909,

An Jung-geun

An Jung-geun (; 2 September 1879 – 26 March 1910) was a Korean independence activist. He is remembered as a martyr in both South and North Korea for his 1909 assassination of the Japanese politician Itō Hirobumi, who had previously served a ...

infamously assassinated Itō Hirobumi, and gave this incident as one of his reasons for doing so.

This incident, as well as the , ultimately lead to the rise of various civilian anti-Japanese and anti-government militias called

righteous armies

Righteous armies (), sometimes translated as irregular armies or militias, were informal civilian militias that appeared several times in Korean history, when the national armies were in need of assistance.

The first righteous armies emerged du ...

.

Analysis

Historian of Japan Peter Duus has called this assassination a "hideous event, crudely conceived and brutally executed".

Advisor to Gojong

Homer B. Hulbert wrote of the assassination in 1905. He believed that the mainstream Japanese government was not involved in plotting the assassination. He theorised that the government of Japan were possibly only to blame for having appointed a man of Count Miura's temperament as their representative in Joseon. The arrest of Miura and his Japanese conspirators was sufficient in itself to destabilise their Korean followers' positions.

Seredin-Sabatin's account

In 2005, professor Kim Rekho () of the

Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across the Russian Federation; and additional scientific and social units such ...

came across a written account of the incident by a Russian architect

Afanasy Seredin-Sabatin

Afanasii Ivanovich Seredin-Sabatin (Афанасий Иванович Середин-Сабатин) was a Russian steersman-pilot and reporter for an English newspaper, but is best known as the first European (Russian) architect to live and work ...

in the . The document was released to the public on 11 May 2005.

Almost five years before the document's release in South Korea, a translated copy was in circulation in the United States, having been released by the Center for Korean Research of

Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

on 6 October 1995 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Eulmi Incident.

In the account, Seredin-Sabatin recorded:

Apology

In May 2005, 84-year-old , the grandson of

Kunitomo Shigeaki, paid his respects to Empress Myeongseong at her tomb in

Namyangju

Namyangju (; ) is a city in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. To the east is Gapyeong County, to the west is Guri, and to the north is Pocheon. Namyangju was originally a southern part of Yangju-gun, but was separated into Namyangju-gun in April ...

,

Gyeonggi

Gyeonggi Province (, ) is the most populous province in South Korea.

Seoul, the nation's largest city and capital, is in the heart of the area but has been separately administered as a provincial-level ''special city'' since 1946. Incheon, ...

, South Korea.

He apologized to Empress Myeongseong's tomb on behalf of his grandfather; however, the apology was not well received as the descendants of Empress Myeongseong argued that the apology had to be made on a governmental level.

Since 2009, several South Korean non-governmental organizations have been attempting to sue the Japanese government for its complicity in the murder of Queen Min. "Japan has not made an official apology or repentance 100 years after it obliterated the Korean people for 35 years through the 1910 Korea-Japan Annexation Treaty," the suit alleged. The lawsuit was to be filed if the Japanese government did not accept their demand to issue a special statement on 15 August offering the emperor's apology and promising to release relevant documents on the murder case.

Perpetrators

Groups

* , a joint military unit (

Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

and

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

) who provided security for the Japanese legation. It was commanded by legation minister

Miura Gorō

Viscount was a lieutenant general in the early Imperial Japanese Army; he is notable for orchestrating the murder of Queen Min of Korea in 1895.

Biography

Miura was born in Hagi in Chōshū Domain (modern Yamaguchi Prefecture), to a ''s ...

.

* Japanese Legation Security Police Officers, commanded by legation minister

Miura Gorō

Viscount was a lieutenant general in the early Imperial Japanese Army; he is notable for orchestrating the murder of Queen Min of Korea in 1895.

Biography

Miura was born in Hagi in Chōshū Domain (modern Yamaguchi Prefecture), to a ''s ...

and led by

MOFA at the scene. The Japanese Legation Security Police Officers wore plain clothes during the Eulmi Incident.

* Three battalions of the

Hullyŏndae

The Hullyŏndae () was an infantry regiment of the Joseon Army (1881–1897), Joseon Army established under Empire of Japan, Japanese direction as a part of the second Gabo Reform in 1895, the 32nd year of Gojong of Korea's reign. On January 17 i ...

, commanded by Major (1st battalion), Major Yi Tuhwang (2nd battalion), and Major Yi Chinho (3rd battalion). Hullyŏndae commander Lieutenant Colonel Hong Kyehun did not notice the betrayal by his officers and was killed in action by his own men.

* At least four officers who served as military advisors and instructors of the Hullyŏndae, including . The IJA Keijō Garrison was commanded by the

Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office

The , also called the Army General Staff, was one of the two principal agencies charged with overseeing the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA).

Role

The was created in April 1872, along with the Navy Ministry, to replace the Ministry of Military Af ...

, but Second Lieutenant Miyamoto's crew joined in the Eulmi Incident without permission from the IJA General Staff Office.

* More than four dozen

ronin disguised as Japanese officials, including

Adachi Kenzō

was a Japanese politician active during the Taishō and early Shōwa periods.

He participated in the 1895 assassination of the Korean queen.

Biography

Adachi was the son of a samurai in the service of the Hosokawa clan of Kumamoto Domain. Af ...

. They took the role of a vanguard. According to a secret report by Ishizuka Eizo, most of them originally came from

Kumamoto Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located on the island of Kyūshū. Kumamoto Prefecture has a population of 1,748,134 () and has a geographic area of . Kumamoto Prefecture borders Fukuoka Prefecture to the north, Ōita Prefecture t ...

and were armed with

katana

A is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard and long grip to accommodate two hands. Developed later than the ''tachi'', it was used by samurai in feudal Japan and worn with the edge fa ...

s and handguns. (On 3 December 1965, Japanese politician mentioned part of Ishizuka Eizo's secret report in the ,

House of Councillors

The is the upper house of the National Diet of Japan. The House of Representatives (Japan), House of Representatives is the lower house. The House of Councillors is the successor to the pre-war House of Peers (Japan), House of Peers. If the t ...

).

Individuals

In Japan, 56 men were charged. All were acquitted by the

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui has b ...

court due to a lack of evidence. The factual findings of the Hiroshima investigating court were translated into English and printed, and were cited in scholarly works by 1905.

They included (among others):

* Viscount

Miura Gorō

Viscount was a lieutenant general in the early Imperial Japanese Army; he is notable for orchestrating the murder of Queen Min of Korea in 1895.

Biography

Miura was born in Hagi in Chōshū Domain (modern Yamaguchi Prefecture), to a ''s ...

, Japanese legation minister.

*

Adachi Kenzō

was a Japanese politician active during the Taishō and early Shōwa periods.

He participated in the 1895 assassination of the Korean queen.

Biography

Adachi was the son of a samurai in the service of the Hosokawa clan of Kumamoto Domain. Af ...

, former samurai and head of the ''

Kanjō Shinpō

in Shinto terminology indicates a propagation process through which a ''kami'', previously divided through a process called '' bunrei'', is invited to another location and there re-enshrined.

Evolution of the ''kanjō'' process

''Kanjō'' wa ...

''

* , a legation official

[Peter Duus, ''The Abacus and the Sword'', p.76] and former Japanese Army officer

* , businessman

* Kokubun Shōtarō, Japanese legation officials

* Chief Inspector Hagiwara Hidejiro, Officer , Officer , Officer , Officer , Officer , Officer , Officer , Japanese legation officials (Japanese Legation Security Police)

* , a second Secretary of the Japanese legation, Legation minister Miura's inner circle. In his autobiography "Meiji 17~18 Year, The Record of the torment in Korea (明治廿七八年在韓苦心録)", he unilaterally claims that the Eulmi Incident was his own scheme, not Miura's.

* Lieutenant Colonel

Kusunose Yukihiko

was a general in the early Imperial Japanese Army.

Biography

Kusunose was born as the eldest son to a samurai family of the Tosa Domain (present day Kōchi Prefecture). He entered the Imperial Japanese Army in December 1880, serving in artillery ...

, an artillery officer in the

Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

and

at the Japanese legation in Korea, Legation minister Miura's inner circle.

* ,

[Peter Duus, ''The Abacus and the Sword'', p.111] one of the original ("Society for Political Education") members

*

Shiba Shirō

Shiba may refer to:

*Shiba Inu, a breed of dog

*Shiba clan, Japanese clan originating in the Sengoku period

* Shiba Inu (cryptocurrency), a decentralized cryptocurrency

Geography

*Shiba, Tokyo, a former ward of Tokyo, Japan

*Shiba Park in Tokyo

* ...

(柴四朗), former samurai, private secretary to the Minister of Agriculture and Commerce of Japan, and writer who studied political economy at the

Wharton School

The Wharton School ( ) is the business school of the University of Pennsylvania, a private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia. Established in 1881 through a donation from Joseph Wharton, a co-founder of Bethlehem Steel, the Wharton ...

and

Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

.

He had a close connection with Japanese legation minister

Miura Gorō

Viscount was a lieutenant general in the early Imperial Japanese Army; he is notable for orchestrating the murder of Queen Min of Korea in 1895.

Biography

Miura was born in Hagi in Chōshū Domain (modern Yamaguchi Prefecture), to a ''s ...

because Shiba contributed Miura becoming a resident legation minister in Korea.

* , a physician

* Terasaki Yasukichi (寺崎泰吉), a medicine peddler

*

Nakamura Tateo (中村楯雄)

* ; in 2021, a letter was found which was sent by him to his friend which writes about how the assassination happened and how easy it was.

*

Ieiri Kakitsu (家入嘉吉)

*

Kikuchi Kenjō Kikuchi, often written 菊池 or 菊地, may refer to:

Places

* Kikuchi, Kumamoto

* Kikuchi River, Kumamoto

* Kikuchi District, Kumamoto

People

* Kikuchi (surname)

* Kikuchi clan

* Yoshihiko Kikuchi

* Yusei Kikuchi

Other

* Kikuchi disease, a ra ...

(菊池 謙讓)

*

*

Ogihara Hidejiro (荻原秀次郎)

*

Kobayakawa Hideo (小早川秀雄), editor in chief of ''Kanjō shinpō''

*

Sasaki Masayuki

*

Isujuka Eijoh[Joseph Cummins. ''History's Great Untold Stories''.]

In Korea, King Gojong declared that the following were the 'Eulmi Four Traitors ()' on 11 February 1896:

*

*

Yu Kil-chun

Yu Kil-chun (; November 21, 1856 – September 30, 1914) was a Korean politician. Yu lived during the last few decades of Joseon and the Korean Empire, before the occupation of the peninsula by Japan. As a young man, he studied the Chinese cl ...

*

Kim Hong-jip

Kim Hong-jip (; 1842 – February 11, 1896) was a Korean politician best known for his role as prime minister during the Kabo Reform period from 1895–1896. His name was originally Kim Goeng-jip () which he later changed to Kim Hong-jip ...

*

New pieces of information appeared in 2021 in the form of private letters written by a Japanese consular officer to his best friend in Japan. Eight letters (apparently traded for the stamps on the envelopes) were sent by Kumaichi Horiguchi to Teisho Takeishi detailing Horiguchi's part in the slaying.

See also

*

Japanese occupation of Gyeongbokgung

The Japanese occupation of Gyeongbokgung Palace () or the Gabo Incident occurred on 23 July 1894, during the ceasefire of the Donghak Peasant Revolution and the beginning of the First Sino-Japanese War. Imperial Japanese forces led by Japanes ...

* : Theories that Gojong was poisoned by Japanese agents in 1919.

Notes

References

Sources

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Myeongseong

Assassinations

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

1895 murders in Asia

1895 in Korea

Mass murder in 1895

October 1895

19th century in Seoul

Diplomatic crises of the 19th century

Assassinations in Asia

Japan–Korea relations

Mass stabbings in Asia

Sword attacks in Asia

Mass murder in Korea

Military history of Seoul

Attacks on official residences

Historical controversies

Anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea

Adachi Kenzō

Looting in Korea

History of Gyeongbokgung

Regicides

Attacks on government buildings and structures in Korea

Attacks on residential buildings in Korea

One prominent faction was led by the father of King Gojong: the

One prominent faction was led by the father of King Gojong: the  Beginning around the 1860s, groups of young men called ' () emerged in Japan and engaged in political violence. They were seen in Japan as violent thugs and looked down upon. They were the product of groups such as the ''shishi'' and rebel Satsuma Army. Beginning in the 1880s, a number of them moved to Korea. In Korea, they had the right of

Beginning around the 1860s, groups of young men called ' () emerged in Japan and engaged in political violence. They were seen in Japan as violent thugs and looked down upon. They were the product of groups such as the ''shishi'' and rebel Satsuma Army. Beginning in the 1880s, a number of them moved to Korea. In Korea, they had the right of  The ''sōshi'' became fixated on the politically-active Korean queen. According to historian Danny Orbach, a mix of sexism, racism, and political agendas led to members of the ''Kanjō shinpō'' taking the lead in plotting her assassination. They began to romanticize her killing; in his memoirs, founder of the ''Kanjō shinpō''

The ''sōshi'' became fixated on the politically-active Korean queen. According to historian Danny Orbach, a mix of sexism, racism, and political agendas led to members of the ''Kanjō shinpō'' taking the lead in plotting her assassination. They began to romanticize her killing; in his memoirs, founder of the ''Kanjō shinpō''  Around 19 September 1895, Miura met with Adachi. According to Adachi's testimony, Miura euphemistically asked Adachi if he knew of any young men available for a "fox hunt" (), and Adachi enthusiastically agreed. He wrote that "his heart leaped with joy" when Miura shared his plan. Adachi cautioned that the ''Kanjō shinpō'' staff were gentle by nature, and that he wanted to recruit others for the plot. Miura rejected this, and asked that Adachi use all of his employees in the interest of secrecy. Adachi recruited all of the ''Kanjō shinpō'' staff for the task, and a group of other ''sōshi''.

The men were reportedly greatly excited about the coming attack. Journalist Kobayakawa Hideo reportedly almost burst into tears when he was initially told to stay behind, and later claimed that he felt like he was among "heroes of a novel" during the assassination. reportedly told Adachi's wife that she "must be sorry he wasborn a woman", because she could not join the assassins.

Around 19 September 1895, Miura met with Adachi. According to Adachi's testimony, Miura euphemistically asked Adachi if he knew of any young men available for a "fox hunt" (), and Adachi enthusiastically agreed. He wrote that "his heart leaped with joy" when Miura shared his plan. Adachi cautioned that the ''Kanjō shinpō'' staff were gentle by nature, and that he wanted to recruit others for the plot. Miura rejected this, and asked that Adachi use all of his employees in the interest of secrecy. Adachi recruited all of the ''Kanjō shinpō'' staff for the task, and a group of other ''sōshi''.

The men were reportedly greatly excited about the coming attack. Journalist Kobayakawa Hideo reportedly almost burst into tears when he was initially told to stay behind, and later claimed that he felt like he was among "heroes of a novel" during the assassination. reportedly told Adachi's wife that she "must be sorry he wasborn a woman", because she could not join the assassins.

According to the verdict of the preliminary court in Hiroshima, the plan was formally approved in a meeting at the Japanese Legation on 3 October in a meeting between Miura, , and .

According to the verdict of the preliminary court in Hiroshima, the plan was formally approved in a meeting at the Japanese Legation on 3 October in a meeting between Miura, , and .

It is not known who killed the queen. Several people boasted of the achievement, with Keene evaluating some testimonies as unconvincing. It was possibly ''sōshi'' Takahashi Genji (alias Terasaki Yasukichi) or a Japanese army lieutenant.

Takahashi later testified:

According to the testimony of the Korean

It is not known who killed the queen. Several people boasted of the achievement, with Keene evaluating some testimonies as unconvincing. It was possibly ''sōshi'' Takahashi Genji (alias Terasaki Yasukichi) or a Japanese army lieutenant.

Takahashi later testified:

According to the testimony of the Korean  At 8 a.m. on the 9th, Miura telegraphed Japanese acting foreign minister

At 8 a.m. on the 9th, Miura telegraphed Japanese acting foreign minister