Aspasia Manos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aspasia Manou (; 4 September 1896 – 7 August 1972) was a

Aspasia was born in Tatoi,

Aspasia was born in Tatoi,

/ref> Petros Manos and Maria Argyropoulos were second cousins, both being descendants of the most prominent Greek Phanariote families of

etrieved 16 July 2016 wife of Christos Zalokostas, former Olympian athlete, writer and later an industrialist. From her father's second marriage to Sophie Tombazis-Mavrocordato (b. 1875) (daughter of Alexandros Tombazis and his wife, Princess Maria Mavrocordato), she had one half-sister, Rallou (1915–1988), a modern dancer, choreographer and a dance teacher, who was married to a prominent Greek architect Pavlos Mylonas.

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

aristocrat who became the wife of Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon from 495 to 454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Alexander I Theopator Euergetes, surnamed Balas, ruler of the Seleucid Empire 150-145 BC

* Pope Alex ...

, King of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece was ruled by the House of Wittelsbach from 1832 to 1862 and by the House of Glücksburg from 1863 to 1924 and, after being temporarily abolished in favor of the Second Hellenic Republic, again from 1935 to 1973, when it ...

. Due to the controversy over her marriage, she was styled Madame Manou instead of "Queen Aspasia", until recognized as Princess Aspasia of Greece and Denmark after Alexander's death and the restoration of King Constantine I

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

, on 10 September 1922. Through her marriage, she and her descendants were the only ethnically Greek members of the Greek royal family

The Greek royal family () was the ruling family of the Kingdom of Greece from 1863 to 1924 and again from 1935 to 1973. The Greek royal family is a branch of the Danish royal family, itself a cadet branch of the House of Glücksburg. The famil ...

, which originated in Denmark.

Daughter of Colonel Petros Manos, aide-de-camp to King Constantine I of Greece, and Maria Argyropoulos (Petros Manos and Maria Argyropoulos were both descendants of most prominent Greek Phanariote families of Constantinople and descendants of ruling Princes of Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

, Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ; : , : ) is a historical and geographical region of modern-day Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia was traditionally divided into two sections, Munteni ...

and Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

), Aspasia grew up close to the royal family. After the divorce of her parents, she was sent to study in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

. She returned to Greece in 1915 and met Prince Alexander, to whom she became secretly engaged due to the expected refusal of the royal family to recognize the relationship of Alexander I with a woman who did not belong to one of the European ruling dynasties.

Meanwhile, the domestic situation in Greece was complicated by World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. King Constantine I abdicated in 1917 and Alexander was chosen as sovereign. Separated from his family and subjected to the Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Cretan State, Cretan Greeks, Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. As the leader of the Liberal Party (Greece), Liberal Party, Venizelos ser ...

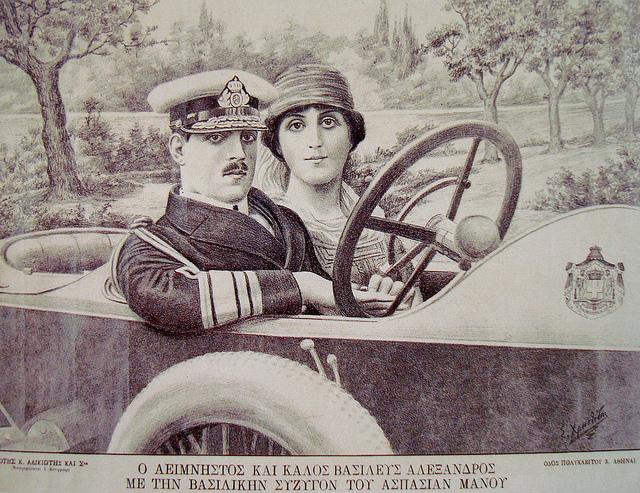

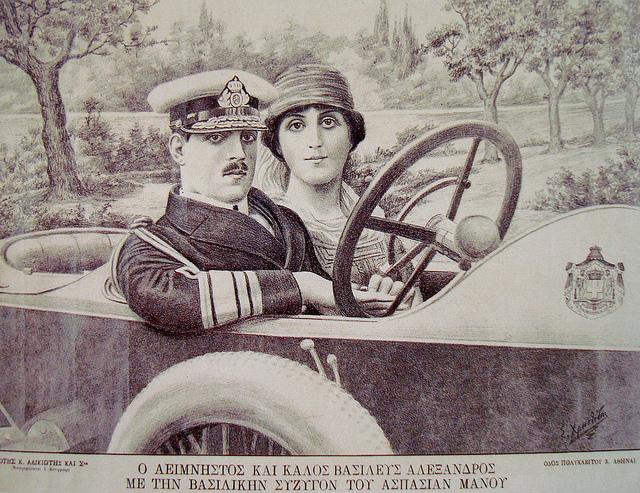

, the new ruler found comfort in Aspasia. Despite the opposition of his parents (exiled in Switzerland) and Venizelists (who wanted the king to marry a British princess), King Alexander I secretly married Aspasia on 17 November 1919. The public revelation of the wedding shortly after caused a huge scandal, and Aspasia temporarily left Greece. However, she was reunited with her husband after a few months of separation and was then allowed to return to Greece without receiving the title of Queen of the Hellenes. She became pregnant, but Alexander died on 25 October 1920, less than a year after their marriage.

At the same time, the situation in Greece was deteriorating again: the country was in the middle of a bloody conflict with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, Constantine I was restored (19 December 1920) only to be deposed again (27 September 1922), this time in favor of ''Diadochos'' (Crown Prince) George. Initially excluded from the royal family, Aspasia was gradually integrated after the birth of her daughter Alexandra

Alexandra () is a female given name of Greek origin. It is the first attested form of its variants, including Alexander (, ). Etymology, Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; genitive, GEN , ; ...

on 25 March 1921 and was later recognized with the title of Princess Alexander of Greece and Denmark after a decree issued by her father-in-law. Nevertheless, her situation remained precarious due to the dislike of her sister-in-law Elisabeth of Romania

Elisabeth of Romania (Elisabeth Charlotte Josephine Alexandra Victoria; , , Romanization, romanized: ''Elisábet''; 12 October 1894 – 14 November 1956) was the second child and eldest daughter of Ferdinand I of Romania, King Ferdinand I an ...

and the political instability of the country. As the only members of the royal family to be allowed to stay in Greece after the proclamation of the Republic on 25 March 1924, Aspasia and her daughter chose to settle in Florence, with Queen Sophia. They remained there until 1927 then divided their time between the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

.

The restoration of the Greek monarchy in 1935 did not change Aspasia's life. Sheltered by her in-laws, she made the Venetian villa ''Garden of Eden'' her main residence, until the outbreak of the Greco-Italian War

The Greco-Italian War (), also called the Italo-Greek War, Italian campaign in Greece, Italian invasion of Greece, and War of '40 in Greece, took place between Italy and Greece from 28 October 1940 to 23 April 1941. This conflict began the Balk ...

in 1940. After a brief return to her country, where she worked for the Red Cross

The organized International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 16million volunteering, volunteers, members, and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ...

, the princess spent World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in England. In 1944, her daughter married the exiled King Peter II of Yugoslavia

Peter II Karađorđević (; 6 September 1923 – 3 November 1970) was the last King of Yugoslavia, reigning from October 1934 until he was deposed in November 1945. He was the last reigning member of the Karađorđević dynasty.

The eldest ...

, and Aspasia became a grandmother with the birth of Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia

Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia (; born 17 July 1945), is the head of the Karađorđević dynasty, House of Karađorđević, the former royal house of the defunct Kingdom of Yugoslavia and its predecessor the Kingdom of Serbia. Alexander ...

in 1945. Once peace was restored, Aspasia returned to live in Venice. Her last days were marked by economic hardship, illness and especially worry for her daughter, who made several suicide attempts. Aspasia died in 1972, but it was not until 1993 that her remains were transferred to the royal necropolis of Tatoi.

Family

Aspasia was born in Tatoi,

Aspasia was born in Tatoi, Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

on 4 September 1896 as the eldest daughter of Petros Manos, a Colonel in the Hellenic Army

The Hellenic Army (, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the army, land force of Greece. The term Names of the Greeks, '' Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the largest of the three branches ...

, and his first wife, Maria Argyropoulos (1874-1930).Manos family/ref> Petros Manos and Maria Argyropoulos were second cousins, both being descendants of the most prominent Greek Phanariote families of

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

and the descendants of the ruling Princes of Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

, Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ; : , : ) is a historical and geographical region of modern-day Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia was traditionally divided into two sections, Munteni ...

and Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

(commonly known as Danubian Principalities

The Danubian Principalities (, ) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th century. The term was coined in the Habsburg monarchy after the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) ...

). Named after her maternal grandmother, Aspasia Anargyrou Petrakis, daughter of Anargyros Petrakis (1793-1876), the first modern Mayor of Athens

The mayor of Athens is the head of Athens#municipality of Athens, Athens. The current mayor is Haris Doukas who assumed office on 1 January 2024.

Kingdom of Greece (1832–1924)

Second Hellenic Republic (1924–1935)

Kingdom of Greece (1935 ...

, she had one younger full-sister, Roxane (born 28 February 1898),''Colonel Petros (Thrasybulos) Manos, 9G Grandson'' in: christopherlong.co.uketrieved 16 July 2016 wife of Christos Zalokostas, former Olympian athlete, writer and later an industrialist. From her father's second marriage to Sophie Tombazis-Mavrocordato (b. 1875) (daughter of Alexandros Tombazis and his wife, Princess Maria Mavrocordato), she had one half-sister, Rallou (1915–1988), a modern dancer, choreographer and a dance teacher, who was married to a prominent Greek architect Pavlos Mylonas.

Early years

After the divorce of her parents, Aspasia left Athens to complete her studies in France and Switzerland.Mateos Sainz de Medrano 2004, p. 176.Van der Kiste 1994, p. 117. Having returned to Greece in 1915, she came to live with her mother. Shortly after, she met her childhood friend, Prince Alexander of Greece, at a party given by the Palace Stable master, Theodoros Ypsilantis. Described by many of her contemporaries as a very beautiful woman, Aspasia immediately caught the attention of the prince who then had no other wish than to conquer her.Secret engagement

Initially, Aspasia was very reluctant to accept the romantic advances of the prince. Renowned for his many female conquests, Alexander seemed to her untrustworthy, also because their social differences impeded any serious relationship. However, the perseverance of the Greek prince, who travelled toSpetses

Spetses (, "Pityussa") is an island in Attica, Greece. It is counted among the Saronic Islands group. Until 1948, it was part of the old prefecture of Argolis and Corinthia Prefecture, which is now split into Argolis and Corinthia. In ancient ...

in the summer of 1915 for the sole purpose of seeing Aspasia, finally overcame her misgivings.

Deeply in love with each other, they became engaged but their marital project remained secret. Alexander's parents, especially Queen Sophia (born a Prussian princess of the House of Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, ; , ; ) is a formerly royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) German dynasty whose members were variously princes, Prince-elector, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern Castle, Hohenzollern, Margraviate of Bran ...

), were very attached to social conventions, making it unthinkable that their children could marry persons not belonging to European royalty.Van der Kiste 1994, p. 118.

World War I and its consequences

Accession to the throne of Alexander I

DuringWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, King Constantine I

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

(who ascended to the throne in 1913 following the assassination of his father, King George I) kept Greece in a policy of neutrality towards the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

and the other powers of the Triple Alliance Triple Alliance may refer to:

* Aztec Triple Alliance (1428–1521), Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan and in central Mexico

* Triple Alliance (1596), England, France, and the Dutch Republic to counter Spain

* Triple Alliance (1668), England, the ...

. Brother-in-law of Emperor William II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as the Hohenzollern dynasty's ...

, the Greek sovereign was accused by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

of being pro-German because he spent part of his military training in Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

. This situation led to a rupture between the sovereign and his Prime Minister, Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Cretan State, Cretan Greeks, Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. As the leader of the Liberal Party (Greece), Liberal Party, Venizelos ser ...

, who was convinced of the need to support the countries of the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

to link the Greek minorities of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

and the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

to the Hellenic Kingdom. In the end, King Constantine was deposed in 1917 and replaced by his second son Prince Alexander, considered more malleable than his elder brother ''Diadochos'' George by the Triple Entente.

On the day of his accession to the throne, 10 June 1917, Alexander I revealed to his father his relationship with Aspasia and asked him for permission to marry her. Very reluctant to approve what he considered a ''mésalliance'', Constantine asked his son to wait until the end of the war to marry. In return, the deposed King promised to be his son's witness at his wedding day. In these circumstances, Alexander agreed to postpone his projected marriage until the restoration of peace. Two days later, Constantine and his relatives arrived at the small port of Oropos

Oropos () is a small town and a municipality in East Attica, Greece.

The village of Skala Oropou, within the bounds of the municipality, was the site an important ancient Greek city, Oropus, and the famous nearby sanctuary of Amphiaraos is sti ...

and went into exile; it was the last time that Alexander was in contact with his family.

A bond considered unequal

Once his family went into exile, Alexander I found himself completely isolated by Eleftherios Venizelos and his supporters. The entire staff of the crown was gradually replaced by the enemies of Constantine I, and his son was forced to dismiss his friends when they were not simply arrested. Even the portraits of the dynasty were removed from the palaces, and sometimes the new ministers called him, in his presence, "son of the traitor". Prisoner in his own kingdom, the young monarch took very badly the separation from his family. He regularly wrote letters to his parents, but they were intercepted by the government and his family didn't receive them. Under these conditions, the only comfort of Alexander was Aspasia and he decided to marry her despite the recommendations of his father and the opposition of the Prime Minister. Indeed, Eleftherios Venizelos, despite being previously a friend of Petros Manos (Aspasia's father), feared that she used her family connections to mediate between Alexander I and his parents.Llewellyn Smith 1998, p. 136. Above all, the Prime Minister would have preferred that the monarch should marry Princess Mary of the United Kingdom to strengthen the ties between Greece and the Triple Entente. However, the relationship of Alexander I and Aspasia did not only have enemies. The Greek royal dynasty was indeed of German origin and to findByzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

ancestors to them they had to go back to the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. In these circumstances, the union of the monarch and his fiancée would effectively Hellenize the dynasty, which would not displease all the Greeks. Finally, in the same foreign powers, particularly the British Embassy, the assumption of this marriage was seen favorably. Indeed, the influence of Aspasia on the sovereign was found to be positive,Mateos Sainz de Medrano 2004, p. 177. because she gave to him the strength to remain in the throne. The official visit of Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn

Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn (Arthur William Patrick Albert; 1 May 185016 January 1942) was the seventh child and third son of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. He served as Gove ...

, to Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

in March 1918 also confirmed the support of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

to the marriage project. The son of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

in fact requested to meet Aspasia and then told Alexander I that if he had been younger, he too would have sought to marry her.

Scandalous marriage

Secret wedding

Faced with the complete opposition of both the government and royal family, Alexander I and Aspasia decided to marry secretly. With the help of Aspasia's brother-in-law, Christos Zalokostas, and after three attempts, the couple managed to be wedded by theArchimandrite

The title archimandrite (; ), used in Eastern Christianity, originally referred to a superior abbot ('' hegumenos'', , present participle of the verb meaning "to lead") whom a bishop appointed to supervise several "ordinary" abbots and monaste ...

Zacharistas in the evening of 17 November 1919. After the ceremony (which also included a civil wedding

A wedding is a ceremony in which two people are united in marriage. Wedding traditions and customs vary greatly between cultures, ethnicities, races, religions, denominations, countries, social classes, and sexual orientations. Most wedding ...

), the archimandrite swore to keep silent about it, but he quickly broke his promise and confessed the whole affair to the Metropolitan Meletius III of Athens. Through her marriage, she and her descendants would become the only ethnically Greek members of the Greek royal family

The Greek royal family () was the ruling family of the Kingdom of Greece from 1863 to 1924 and again from 1935 to 1973. The Greek royal family is a branch of the Danish royal family, itself a cadet branch of the House of Glücksburg. The famil ...

, which originated in Denmark.

According to the Greek constitution, members of the royal family are not only obliged to obtain the permission of the sovereign to marry but also of the head of the Church of Greece

The Church of Greece (, ), part of the wider Greek Orthodox Church, is one of the autocephalous churches which make up the communion of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Its canonical territory is confined to the borders of Greece prior to th ...

. By marrying Aspasia without the consent of the Metropolitan, Alexander I had not complied with the law, causing a huge scandal in the country. Although the marriage of the young couple was retroactively recognized as legal (but non-dynastic) following Alexander's death, Aspasia was never entitled to be known as "Queen of the Hellenes"; she was instead styled "Madame Manos".Van der Kiste 1994, p. 119.

Unequal marriage

Despite his anger at the wedding, Eleftherios Venizelos permitted, initially, that Aspasia and her mother move to the Royal Palace with the condition that the marriage not be made public. However, the secret was soon discovered and Aspasia was forced to leave Greece to escape the scandal. Exiled, she settled first inRome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

and then in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

.Mateos Sainz de Medrano 2004, p. 178. Alexander I was allowed to join her in the French capital six months later. Officially, the monarch made a state visit to the Allies' heads of state gathered at the Peace Conference

A peace conference is a diplomatic meeting where representatives of states, armies, or other warring parties converge to end hostilities by negotiation and signing and ratifying a peace treaty.

Significant international peace conferences in ...

. In reality, the stay was something of a honeymoon for the couple.

Finally, Aspasia and her husband received permission from the government to get back together in Greece during summer 1920. In the Hellenic capital, "Madame Manos" was firstly in her sister's house before moving to Tatoi Palace

Tatoi (, ) was the summer palace and estate of the former Greek royal family. The area is a densely wooded southeast-facing slope of Mount Parnitha, and its ancient and current official name is Decelea, Dekeleia. It is located from the cit ...

. It was during this period that she became pregnant, an event that caused great joy to the couple.

Death of Alexander I

On 2 October 1920, King Alexander I had an accident when he took a walk on the lands of the domain of Tatoi. Amacaque

The macaques () constitute a genus (''Macaca'') of gregarious Old World monkeys of the subfamily Cercopithecinae. The 23 species of macaques inhabit ranges throughout Asia, North Africa, and Europe (in Gibraltar). Macaques are principally f ...

who belonged to the manager of the vineyards of the palace attacked Fritz, the German shepherd dog

The German Shepherd, also known in Britain as an Alsatian, is a German breed of working dog of medium to large size. The breed was developed by Max von Stephanitz using various traditional German herding dogs from 1899.

It was originally b ...

of the sovereign, and he attempted to separate the two animals. As he did so, another monkey attacked Alexander and bit him deeply on the leg and torso. Eventually, servants arrived and chased away the monkeys (which were later destroyed), and the King's wounds were promptly cleaned and dressed but not cauterize

Cauterization (or cauterisation, or cautery) is a medical practice or technique of burning a part of a body to remove or close off a part of it. It destroys some tissue in an attempt to mitigate bleeding and damage, remove an undesired growth, or ...

d. He didn't consider the incident serious and asked that it not be publicized.Gelardi 2006, p. 293.

Beginning on the night of the event, Alexander I developed a high fever: his wound had become infected and soon developed into septicaemia

Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.

This initial stage of sepsis is followed by suppression of the immune system. Common signs and s ...

. With the rapid evolution of his illness, doctors planned to amputate his leg but no one wanted to take responsibility for such an act. Operated on seven times, he was cared for only by Aspasia during the four weeks of his illness. Under the effect of the blood poisoning, the young King suffered terribly and his cries of pain were heard in the entire Royal Palace. On 19 October, he became delirious and called out for his mother. However, the Greek government refused to allow Queen Sophia to re-enter the country. In St. Moritz

St. Moritz ( , , ; ; ; ; ) is a high Alpine resort town in the Engadine in Switzerland, at an elevation of about above sea level. It is Upper Engadine's major town and a municipality in the administrative region of Maloja in the Swiss ...

, where she was exiled with the rest of the royal family, the Queen begged the Hellenic authorities to let her take care of her son but Venizelos remained adamant. Finally, Dowager Queen Olga

Olga may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Olga (name), a given name, including a list of people and fictional characters named Olga or Olha

* Michael Algar (born 1962), English singer also known as "Olga"

Places

Russia

* Olga, Russia ...

, widow of George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George of Beltan (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgoruk ...

, was allowed to travel alone to Athens to be with her grandson. Delayed by rough seas, however, she arrived twelve hours after the King's death, on 25 October 1920. Informed by telegram that night, other members of the royal family learned of the death with sadness.

Two days after the death of the monarch, his funeral service was held in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens

The Metropolitan Cathedral of the Annunciation (), popularly known as the Metropolis or Mitropoli (), is the cathedral church of the Archbishopric of Athens and all of Greece.

History

Construction of the cathedral began on Christmas Day, 1842 ...

. Once again, the royal family was refused permission to enter Greece; in consequence, apart from Aspasia, only Dowager Queen Olga was present at the funeral. The body of Alexander I was buried in the royal burial ground at Tatoi Palace

Tatoi (, ) was the summer palace and estate of the former Greek royal family. The area is a densely wooded southeast-facing slope of Mount Parnitha, and its ancient and current official name is Decelea, Dekeleia. It is located from the cit ...

.Van der Kiste 1994, p. 125.Mateos Sainz de Medrano 2004, p. 179.

Birth of Alexandra and its consequences

Kingdom without a King

Four months pregnant at the time of her husband's death, Aspasia withdrew to the Diadochos Palace at Athens. In Greece, the unexpected death of Alexander I had much more serious consequences: it raised the question of succession and even the survival of the monarchy. Because the King had married without his father's or the head of Orthodox Church's permission, it was technically illegal, the marriage void, and the couple's posthumous child illegitimate according to law. Maintaining the monarchy therefore involved finding another sovereign and, as the Venizelists still opposed Constantine I and ''Diadochos'' George, the government decided to offer the crown to another member of the royal family, the young Prince Paul. However, he refused to ascend the throne, which remained resolutely vacant. With Aspasia's pregnancy approaching its end, some plotted to put her child on the throne and rumours even assured that she was a supporter of this solution. The victory of the monarchists in theelections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

of 1 November 1920 changed everything. Dimitrios Rallis

Dimitrios Rallis (Greek: Δημήτριος Ράλλης; 1844–1921) was a Greek politician, founder and leader of the Neohellenic or "Third Party".

Family

He was born in Athens in 1844. He was descended from an old Greek political family. ...

replaced Eleftherios Venizelos as Prime Minister and Constantine I was soon restored.

Gradual integration into the royal family

The restoration of Constantine I at first did not bring any change to Aspasia's situation. Considered intriguing by part of theroyal family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term papal family describes the family of a pope, while th ...

, especially by her sister-in-law Princess Elisabeth of Romania

Elisabeth of Romania (Elisabeth Charlotte Josephine Alexandra Victoria; , , romanized: ''Elisábet''; 12 October 1894 – 14 November 1956) was the second child and eldest daughter of King Ferdinand I and Queen Marie of Romania. She was Qu ...

who hated her, she was under the suspicion that she wanted to put her unborn child on the throne. The royal family feared the birth of a male child, which could further complicate the political situation at a time when Greece was already at war against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. However, not all members of the royal family shared this distrust: Princess Alice of Battenberg

Princess Alice of Battenberg (Victoria Alice Elizabeth Julia Marie; 25 February 1885 – 5 December 1969) was the mother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, mother-in-law of Queen Elizabeth II, and paternal grandmother of King Charles III. Af ...

, aunt of the deceased Alexander I, chose to spend Christmas of 1920 in the company of Aspasia. For her part, Queen Sophia, who previously strongly opposed her son's relationship with Aspasia, approached her daughter-in-law and awaited the birth of her first grandchild.Vickers 2000, p. 152.

The birth of Alexandra

Alexandra () is a female given name of Greek origin. It is the first attested form of its variants, including Alexander (, ). Etymology, Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; genitive, GEN , ; ...

on 25 March 1921 caused a great relief to the royal family: under the terms of the Salic law

The Salic law ( or ; ), also called the was the ancient Frankish Civil law (legal system), civil law code compiled around AD 500 by Clovis I, Clovis, the first Frankish King. The name may refer to the Salii, or "Salian Franks", but this is deba ...

(which prevailed in Greece), the newborn could not claim the crown and she was unlikely to be used to undermine the dynasty. King Constantine I and Dowager Queen Olga therefore accepted easily that they become the godparents of the child. Still, neither the child nor her mother received more official recognition; only in July 1922, and at the behest of Queen Sophia, a law was passed which allowed the King to retroactively recognize marriages of members of the royal family, although on a non-dynastic

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family, usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A dynasty may also be referred to as a "house", "family" or "clan", among others.

Historians ...

basis. With this legal subterfuge, Alexandra obtained the style of ''Royal Highness

Royal Highness is a style used to address or refer to some members of royal families, usually princes or princesses. Kings and their female consorts, as well as queens regnant, are usually styled ''Majesty''.

When used as a direct form of a ...

'' and the title of Princess of Greece and Denmark. Aspasia's status, however, was not changed with the law and she remained a simple commoner

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

to the eyes of protocol

Protocol may refer to:

Sociology and politics

* Protocol (politics)

Protocol originally (in Late Middle English, c. 15th century) meant the minutes or logbook taken at a meeting, upon which an agreement was based. The term now commonly refers to ...

.Mateos Sainz de Medrano 2004, p. 180.

Humiliated by this difference in treatment, Aspasia approached Prince Christopher of Greece (who also married a commoner), and begged him to intercede on her behalf. Moved by the arguments of his niece-in-law, the Prince talked to Queen Sophia, who eventually changed her opinion. Under pressure from his wife, King Constantine I issued a decree, gazette

A gazette is an official journal, a newspaper of record, or simply a newspaper.

In English and French speaking countries, newspaper publishers have applied the name ''Gazette'' since the 17th century; today, numerous weekly and daily newspapers ...

d 10 September 1922 under which Aspasia received the title "Princess of Greece and Denmark" and the style of ''Royal Highness''.

Fall of the monarchy and wandering life

From Athens to Florence

Despite these positive developments, the situation of Aspasia and her daughter did not improve. Indeed, Greece experienced a serious military defeat against Turkey and acoup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

soon forced Constantine I to abdicate in favor of ''Diadochos'' George, on 27 September 1922. Things went from bad to worse for the country, and a failed monarchist coup d'état forced the new King George II and his family into exile in December 1923. Four months later, on 25 March 1924, the Second Hellenic Republic

The Second Hellenic Republic is a modern Historiography, historiographical term used to refer to the Greece, Greek state during a period of republican governance between 1924 and 1935. To its contemporaries it was known officially as the Hellenic ...

was proclaimed and both Aspasia and Alexandra were then the only members of the dynasty allowed to stay in Greece.

Penniless, Aspasia, with her daughter, chose to follow her in-laws to the exile in early 1924. They found refuge with Queen Sophia, who moved to the ''Villa Bobolina'' in Fiesole

Fiesole () is a town and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Florence in the Italian region of Tuscany, on a scenic height above Florence, 5 km (3 miles) northeast of that city. It has structures dating to Etruscan and Roman times.

...

near Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

shortly after the death of her husband in December 1923. The now Dowager Queen, who adored Alexandra, was delighted, even if her financial situation was also precarious.

From London to Venice

In 1927, Aspasia and her daughter moved toAscot, Berkshire

Ascot () is a town in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead, in Berkshire, England. It is south of Windsor, east of Bracknell and west of London.

It is most notable as the location of Ascot Racecourse, home of the Royal Ascot meeti ...

, in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. They were greeted by Sir James Horlick, 4th Baronet

Lieutenant-Colonel Sir James Nockells Horlick, 4th Baronet, OBE, Military Cross, MC (1886–1972) was the second son of Sir James Horlick, 1st Baronet, Sir James Horlick, first holder of the Horlick baronets, Horlick Baronetcy, of Cowley Mano ...

and his Horlick family, who harbored them in their ancestral seat Cowley Manor.Mateos Sainz de Medrano 2004, p. 181. With her personal savings and the financial support of Horlick, Aspasia bought a small property on the Island of Giudecca

Giudecca (; ) is an island in the Venetian Lagoon, in northern Italy. It is part of the ''sestiere'' of Dorsoduro and is a locality of the ''comune'' of Venice.

Geography

Giudecca lies immediately south of the central islands of Venice, from wh ...

in Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

. Former home of Caroline and Frederic Eden, the villa and its 3.6 hectares of landscaped grounds are nicknamed the ''Garden of Eden'', which delighted the Greek princesses.

Possible second marriage

Widow for many years, in 1933 Aspasia had a romantic relationship with the Sicilian Prince Starrabba di Giardinelli, who asked her to marry him. She was about to accept the proposal, when he suddenly fell ill and died oftyphoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

.

Estrangement from the Greek royal family

Restoration of the monarchy and outbreak of World War II

In 1935, the Second Hellenic Republic was abolished and George II was restored to the throne after areferendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

organized by General Georgios Kondylis

Georgios Kondylis (, romanized: ''Geórgios Kondýlis''; 14 August 1878 – 1 February 1936) was a Greek general, politician and prime minister of Greece. He was nicknamed ''Keravnos'', Greek for " thunder" or " thunderbolt".

Military ca ...

. While several members of the royal family decided to return to Greece, Aspasia chose to remain in Italy, but claimed, in the name of her daughter, her rightful share of the inheritance of Alexander I. Unlike Princess Alexandra, Aspasia was subsequently not invited to the ceremonies which marked the return of the remains of King Constantine I, Queen Sophia and Dowager Queen Olga to the Kingdom (1936), or the wedding of her brother-in-law, the ''Diadochos'' Paul, with Princess Frederica of Hanover

Princess Frederica of Hanover (Friederike Sophie Marie Henriette Amelie Therese; 9 January 1848 – 16 October 1926) was a member of the House of Hanover. After her marriage, she lived mostly in England, where she was a prominent member of ...

(1938). Even worse, Aspasia did not have a plot in the royal cemetery of Tatoi, because the grave of her husband was placed next to that of his parents in order to keep him away from his wife even in death.Mateos Sainz de Medrano 2004, p. 181 and 403

The outbreak of the Greco-Italian War

The Greco-Italian War (), also called the Italo-Greek War, Italian campaign in Greece, Italian invasion of Greece, and War of '40 in Greece, took place between Italy and Greece from 28 October 1940 to 23 April 1941. This conflict began the Balk ...

on 28 October 1940 forced Aspasia and Alexandra to suddenly leave fascist Italy. They settled with the rest of the royal family in Athens. Eager to serve her country in this difficult moment, Aspasia helped with the Red Cross

The organized International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 16million volunteering, volunteers, members, and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ...

. However, after several months of victorious battles against the Italian forces, Greece was invaded by the army of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and the majority of the members of the royal family left the country on 22 April 1941. After a brief stay in Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, where they survived a German bombing raid, Aspasia and her family departed for Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

.

Settling in England and Alexandra's marriage

While several members of the royal family were forced to spend World War II in South Africa, Aspasia obtained the permission of King George II of Greece and the British government to move to theUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

with her daughter. Arrived at Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

in the fall of 1941, they settled in Mayfair

Mayfair is an area of Westminster, London, England, in the City of Westminster. It is in Central London and part of the West End. It is between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane and one of the most expensive districts ...

, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. In the English capital, the Greek princesses resumed their activities with the Red Cross. Better accepted than in their own country, they were regularly received by their cousin Marina, Duchess of Kent (born Princess of Greece and Denmark) and, while he was on leave from the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, met the future Duke of Edinburgh

Duke of Edinburgh, named after the capital city of Scotland, Edinburgh, is a substantive title that has been created four times since 1726 for members of the British royal family. It does not include any territorial landholdings and does not pr ...

(born Prince Philip of Greece), who for some time was looked on as a suitable husband for Alexandra.

However, Alexandra soon met and was attracted to another royal figure. In 1942, the Greek princess met King Peter II of Yugoslavia

Peter II Karađorđević (; 6 September 1923 – 3 November 1970) was the last King of Yugoslavia, reigning from October 1934 until he was deposed in November 1945. He was the last reigning member of the Karađorđević dynasty.

The eldes ...

at an officers gala at Grosvenor House

Grosvenor House was one of the largest townhouse (Great Britain), townhouses in London, home of the Grosvenor family (the family of the Dukes of Westminster) for more than a century. Their original London residence was on Millbank, but after t ...

. The 19-year-old sovereign had lived in exile in London since the invasion of his country by the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

in April 1941. They quickly fell in love with each other and eventually were married on 20 March 1944, despite the opposition of the Queen Mother Maria of Yugoslavia

Maria (born Princess Maria of Romania; 6 January 1900 – 22 June 1961), known in Serbian as Marija Karađorđević ( sr-Cyrl, Марија Карађорђевић), was Queen of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from 1922 to 1929 and Queen of Yu ...

(born Princess Maria of Romania). The ceremony was very modest, because of financial difficulties related to the war, but Aspasia, who always wanted to see her daughter marry well, was delighted.

Shortly after the end of the war, on 17 July 1945, Queen Alexandra gave birth to her only child, Crown Prince Alexander of Yugoslavia

Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia (; born 17 July 1945), is the head of the House of Karađorđević, the former royal house of the defunct Kingdom of Yugoslavia and its predecessor the Kingdom of Serbia. Alexander is the only child of Ki ...

, in Suite 212 of Claridge's Hotel

Claridge's is a 5-star hotel at the corner of Brook Street and Davies Street in Mayfair, London. The hotel is owned and managed by the Maybourne Hotel Group.

History Founding

Claridge's traces its origins to Mivart's Hotel, which was founded ...

in Brook Street, London, which according to some reports was transformed for the occasion into Yugoslav territory by the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

. However, the arrival of the heir to the throne was quickly followed by the deposition of the Karađorđević dynasty and the proclamation of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (commonly abbreviated as SFRY or SFR Yugoslavia), known from 1945 to 1963 as the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as Socialist Yugoslavia or simply Yugoslavia, was a country ...

by Marshal Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito ( ; , ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and politician who served in various positions of national leadership from 1943 until his death ...

on 29 November 1945. This was the beginning of a long period of difficulties, marked by financial instability, the pursuit of vain political projects and the deterioration of relations between Alexandra and Peter II.

Later life

Return to Venice and financial difficulties

After the end of World War II, Aspasia decided not to go back to Greece and she returned to Venice, to live once more on the Island of Giudecca. Back in the ''Garden of Eden'', she found her house partially destroyed by the conflict and began to rebuild. Still without sufficient financial resources and concerned about the situation of her daughter (who granted her at one point the guardianship of her grandson Crown Prince Alexander,), Aspasia led a quiet life, punctuated by a few public appearances during cultural events. Over the years, her financial situation deteriorated even further, and during the winter of 1959–1960, the Princess was no longer able to pay the heating bills. She temporarily left the ''Garden of Eden'' and stayed in the hotels ''Europa'' and ''Britannia'' in Venice.Mateos Sainz de Medrano 2004, p. 182. Shortly after, she was forced to sell some furniture and other valuables to pay off her debts.Alexandra's depression and health problems

Demoralised by exile and financial difficulties, the former King Peter II of Yugoslavia gradually became analcoholic

Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World Hea ...

and relieved his boredom by multiplying his affairs with other women. Worn down by the behavior of her husband, with whom she was still in love, Alexandra developed behaviours increasingly dangerous to her health. Probably prone to anorexia

Anorexia nervosa (AN), often referred to simply as anorexia, is an eating disorder characterized by Calorie restriction, food restriction, body image disturbance, fear of gaining weight, and an overpowering desire to be thin.

Individuals wit ...

, in 1950 the former queen undertook a first suicide attempt, while staying with her mother. After several years of wandering between Italy, the United States and France, Alexandra finally moved permanently to the ''Garden of Eden'' after the death of Peter II in 1970.

Aspasia's health and death

Heartbroken by the fate of her daughter, Aspasia saw her own health gradually deteriorate over the years. Seriously ill, she could not attend the wedding of her grandson with Princess Maria da Gloria of Orléans-Braganza on 1 July 1972. One month later, on 7 August 1972, Princess Aspasia died in the ''Ospedale al Mare'' in Venice. At the time, Greece was ruled by theRegime of the Colonels

In politics, a regime (also spelled régime) is a system of government that determines access to public office, and the extent of power held by officials. The two broad categories of regimes are democratic and autocratic. A key similarity acros ...

and so Alexandra chose to bury her mother in the Orthodox section of the cemetery of San Michele island near Venice. Only after the death of Alexandra, in January 1993, were the remains of Aspasia and her daughter transferred to the Royal Cemetery Plot in the park of Tatoi near Dekeleia

Decelea (, ), ''Dekéleia''), was a deme and ancient village in northern Attica serving as a trade route connecting Euboea with Athens, Greece. It was situated near the entrance of the eastern pass across Mount Parnes, which leads from the northe ...

, at the request of Crown Prince Alexander of Yugoslavia.Mateos Sainz de Medrano 2004, p. 182 and 411.

Notes

References

Bibliography

*Gelardi, Julia (2006), ''Born to Rule : Granddaughters of Victoria, Queens of Europe'', Headline Review *Llewellyn Smith, Michael (1998), ''Ionian Vision : Greece in Asia Minor 1919–1922'', London, Hurst & Co *Mateos Sainz de Medrano, Ricardo (2004), ''La Familia de la Reina Sofía, La Dinastía griega, la Casa de Hannover y los reales primos de Europa'', Madrid, La Esfera de los Libros *Palmer, Alan and of Greece, Michael (1990), ''The Royal House of Greece'', Weidenfeld Nicolson Illustrated *Van der Kiste, John (1994), ''Kings of the Hellenes: The Greek Kings, 1863–1974'', Sutton Publishing *Vickers, Hugo (2000), ''Alice, Princess Andrew of Greece'', London, Hamish Hamilton {{DEFAULTSORT:Manos, Aspasia Manos family 1896 births 1972 deaths 20th-century Greek people 20th-century Greek women Greek royaltyAspasia

Aspasia (; ; after 428 BC) was a ''metic'' woman in Classical Athens. Born in Miletus, she moved to Athens and began a relationship with the statesman Pericles, with whom she had a son named Pericles the Younger. According to the traditional h ...

Nobility from Athens

Burials at Tatoi Palace Royal Cemetery

Princesses of Greece

Princesses of Denmark

Princesses by marriage

Morganatic spouses

Royal reburials

People of the Greco-Italian War

Alexander of Greece