Asiatic Despotism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Oriental despotism refers to the

Oriental despotism refers to the

Oriental despotism refers to the

Oriental despotism refers to the Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

view of Asian societies as politically or morally more susceptible to despotic

In political science, despotism () is a form of government in which a single entity rules with absolute power. Normally, that entity is an individual, the despot (as in an autocracy), but societies which limit respect and power to specific gr ...

rule, and therefore different from the democratic West. This view is often pejorative. The term is often associated with Karl August Wittfogel

Karl August Wittfogel (; 6 September 1896 – 25 May 1988) was a German-American playwright, historian, and sinologist. He was originally a Marxist and an active member of the Communist Party of Germany, but after the Second World War, he was ...

's 1957 book ''Oriental Despotism

Oriental despotism refers to the Western view of Asian societies as politically or morally more susceptible to despotic rule, and therefore different from the democratic West. This view is often pejorative. The term is often associated with Karl ...

'', although this work primarily focusses on hydraulic empire

A hydraulic empire, also known as a hydraulic despotism, hydraulic society, hydraulic civilization, or water monopoly empire, is a social or government structure which maintains power and control through exclusive control over access to water. I ...

s.

First articulated explicitly by Aristotle, who contrasted the perceived natural freedom of Greeks with the alleged servitude of Persians and other "barbarian" peoples, the concept was developed extensively in European thought during the Enlightenment. Notably, Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal so ...

, in his influential '' Spirit of the Laws'' (1748), defined Oriental despotism

In political science, despotism () is a government, form of government in which a single entity rules with absolute Power (social and political), power. Normally, that entity is an individual, the despot (as in an autocracy), but societies whi ...

as a distinct type of governance based on absolute power concentrated in the hands of a single ruler, maintained through fear

Fear is an unpleasant emotion that arises in response to perception, perceived dangers or threats. Fear causes physiological and psychological changes. It may produce behavioral reactions such as mounting an aggressive response or fleeing the ...

rather than law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

or tradition

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common e ...

.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the idea of Oriental despotism served both as a theoretical explanation of supposed Eastern political stagnation and as a rhetorical justification for Western colonial and imperial ventures. It evolved further within Marxist thought as part of the " Asiatic mode of production," depicting Asian civilizations as economically stagnant due to centralized control over land and irrigation. In the mid-20th century, Karl Wittfogel's book ''Oriental Despotism

Oriental despotism refers to the Western view of Asian societies as politically or morally more susceptible to despotic rule, and therefore different from the democratic West. This view is often pejorative. The term is often associated with Karl ...

'' (1957) controversially revived the concept, applying it critically to communist states

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state in which the totality of the power belongs to a party adhering to some form of Marxism–Leninism, a branch of the communist ideology. Marxism–Leninism was ...

like the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, describing their centralized bureaucratic

Bureaucracy ( ) is a system of organization where laws or regulatory authority are implemented by civil servants or non-elected officials (most of the time). Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments ...

control as modern forms of ancient despotic governance.

Today, the term "Oriental despotism" is widely recognized as problematic and Eurocentric, largely discredited by contemporary scholarship that emphasizes its ideological

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

underpinnings rooted in colonialism and Orientalist stereotypes. Nevertheless, the concept remains historically significant for understanding Western perceptions of Eastern political institutions, and continues to influence debates about authoritarian governance, East-West distinctions, and post-colonial critiques of historical narratives.

Classical and early modern origins

The concept of "Oriental despotism" first took shape in classical antiquity as a way for Greeks to contrast their own political ethos with that of the "barbarian" East. InAristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's ''Politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

'' (4th century BCE), despotic monarchy was defined as the absolute rule of a master over slaves, a form of monarchy legitimate and hereditary among those who supposedly accepted servitude, unlike tyranny which was illegitimate rule over the unwilling. Aristotle explicitly theorized that while Greeks, by their nature, would not tolerate absolute domination for long, certain non-Greek peoples (exemplified by the Persians) were "by nature" inclined to obey one all-powerful ruler. Despotism, in this view, was natural and even stable among "barbarous" nations but alien to the freedom-loving Greeks. This Greek stereotype of Asiatic peoples as natural slaves underpinned a lasting dichotomy: the "Oriental" world was cast as inherently despotic, opposed to the liberty and civic life of the West. Ancient writers from Aeschylus to Isocrates had already portrayed the Persian Great King as an autocrat over slavish subjects, and Aristotle's theory codified this into political philosophy, making "Oriental despotism" a byword for the antithesis of Greek polity.

Throughout late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

and the medieval era

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and t ...

, this idea persisted and evolved. After Aristotle's works were rediscovered in medieval Europe, scholastic thinkers like Thomas Aquinas and Marsilius of Padua renewed the Aristotelian notion that certain Eastern realms were naturally suited to despotic rule. By the early modern period, European observers applied the term to contemporary empires. Machiavelli in 1513 (though not using the word "despotism") distinguished the Ottoman "state of slaves" (an absolutist sultanate with no intermediate nobility) from the more pluralistic monarchies of Europe. He noted that a regime like Ottoman Turkey

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Central Euro ...

, where the prince held all authority directly, was hard to conquer but easy to hold, whereas a European kingdom with powerful lords was the opposite: an analysis underscoring fundamental East-West differences in governance.

Political theorist Jean Bodin

Jean Bodin (; ; – 1596) was a French jurist and political philosopher, member of the Parlement of Paris and professor of law in Toulouse. Bodin lived during the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation and wrote against the background of reli ...

systematized these contrasts in the late 16th century. Bodin described a type of sovereignty he called monarchie seigneuriale (seignorial or lordly monarchy) in which the ruler's power over subjects was absolute and "limitless, similar to that of a master over slaves". Although Bodin did not use the word "despotism" explicitly, he cited the Ottoman Empire as the prime example: a government where no private property or fundamental law existed to restrain the sovereign, who was sole owner of all land and goods. This he distinguished from a monarchie royale (royal/legitimate monarchy) like France, where property rights, divine and natural laws, and customary legal limits tempered absolutism. Bodin attributed Oriental-style limitless monarchy not to any innate ethnic trait (as Aristotle had) but to historical circumstance: conquest and subjugation in the wake of war. In his view, despotic monarchy was the oldest and most primitive form of regime, capable of long stability, and not confined to Asia: even Charles V's Spanish colonial empire could be seen as despotic since it arose from conquest and lacked traditional checks. Bodin's formulation thus broadened "Oriental despotism" into a trans-historical category of absolute conquest-states, while reinforcing the notion that the Ottoman sultan's rule was fundamentally different from European kingship.

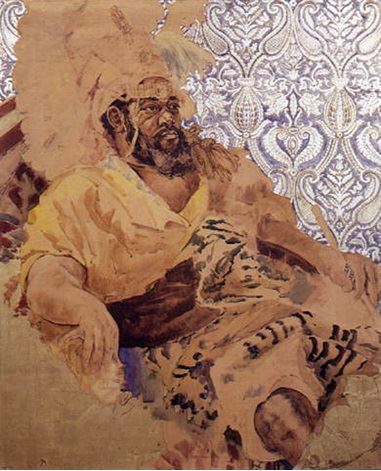

Travelers and missionaries of the 16th and 17th centuries further cemented the concept with empirical detail. Works like Giovanni Botero's ''Relazioni universali'' (1590s) collated reports of Eastern courts and generalized that many Asiatic kingdoms, from Ottoman Turkey and Safavid Persia to Mughal India, China, and Siam, shared a despotic character. This marked an important expansion of the idea beyond the Ottoman example, applying a single model of absolutism across the diverse "Orient". François Bernier

François Bernier (25 September 162022 September 1688) was a French physician and traveller. He was born in Joué-Etiau in Anjou. He stayed (14 October 165820 February 1670) for around 12 years in India.

His 1684 publication "Nouv ...

, a French physician in Mughal India

The Mughal Empire was an early modern empire in South Asia. At its peak, the empire stretched from the outer fringes of the Indus River Basin in the west, northern Afghanistan in the northwest, and Kashmir in the north, to the highlands of pre ...

in the 1660s, gave one of the classic accounts: he depicted the Mughal Empire as tyrannically administered, with crushing taxation

A tax is a mandatory financial charge or levy imposed on an individual or legal person, legal entity by a governmental organization to support government spending and public expenditures collectively or to Pigouvian tax, regulate and reduce nega ...

, no secure private property, and a stark gulf between an all-powerful emperor and the impoverished populace. Bernier argued that the absence of hereditary land rights and the caprice of officials led to economic ruin – a critique that would heavily influence European views of India as the paradigm of oriental misrule. Similarly, Jean Chardin

Jean Chardin (16 November 1643 – 5 January 1713), born Jean-Baptiste Chardin, and also known as Sir John Chardin, was a French jeweller and traveller whose ten-volume book ''The Travels of Sir John Chardin'' is regarded as one of the finest ...

's travels in Safavid Persia

The Guarded Domains of Iran, commonly called Safavid Iran, Safavid Persia or the Safavid Empire, was one of the largest and longest-lasting Iranian empires. It was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often considered the beg ...

(1670s) described an autocratic state where historical contingencies (like the need to suppress an aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

) had concentrated extreme power in the Shah

Shāh (; ) is a royal title meaning "king" in the Persian language.Yarshater, Ehsa, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII, no. 1 (1989) Though chiefly associated with the monarchs of Iran, it was also used to refer to the leaders of numerous Per ...

's hands. Chardin notably downplayed cultural

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

or religious

Religion is a range of social- cultural systems, including designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relate humanity to supernatural ...

explanations: he observed that Persian and Turkish governments differed despite both being Islamic

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

, and concluded that "oriental despotism" took varied forms depending on local circumstances. Such first-hand reports, while sometimes tempering sweeping theories, generally confirmed Europeans' belief that in Asia the ruler's will was law and customary liberties were absent. By 1700, the image of vast Eastern empires ruled by capricious, all-controlling despots, in contrast to Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

's evolving legal-constitutional orders, was firmly established in the Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

imagination.

Enlightenment theories and debates

The 18th-centuryEnlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

made "Oriental despotism" a central concept in political thought. Thinkers of this era used the idea both to analyze Asian governance and to draw contrasts highlighting (or questioning) Europe's superiority. The seminal figure was Charles-Louis de Montesquieu, whose '' Persian Letters'' (1721) and '' Spirit of the Laws'' (1748) gave the classic Enlightenment definition of oriental despotism. Montesquieu argued that of the three basic types of government (republics

A republic, based on the Latin phrase '' res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a state in which political power rests with the public (people), typically through their representatives—in contrast to a monarchy. Although ...

, monarchies

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

, and despotisms) all Asian societies fell into the despotic category. In his taxonomy, a despotism was not merely an abusive monarchy but a distinct form of rule: it was a polity

A polity is a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of political Institutionalisation, institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources.

A polity can be any group of people org ...

in which one individual

An individual is one that exists as a distinct entity. Individuality (or self-hood) is the state or quality of living as an individual; particularly (in the case of humans) as a person unique from other people and possessing one's own needs or g ...

holds all power

Power may refer to:

Common meanings

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power, a type of energy

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

Math ...

, law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

is the ruler's whim, and subjects are treated as passive slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

with no liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

. Crucially, Montesquieu treated this as a system with its own internal logic

In deductive logic, a consistent theory is one that does not lead to a logical contradiction. A theory T is consistent if there is no formula \varphi such that both \varphi and its negation \lnot\varphi are elements of the set of consequences of ...

and stability

Stability may refer to:

Mathematics

*Stability theory, the study of the stability of solutions to differential equations and dynamical systems

** Asymptotic stability

** Exponential stability

** Linear stability

**Lyapunov stability

** Marginal s ...

, not just a degenerated European monarchy. He sought to explain why despotism predominated across the Orient, examining factors from climate to religion. In ''Spirit of the Laws'', Montesquieu famously posited that the vast, fertile plains of Asia and its warm climates facilitated centralized control and pervasive fear

Fear is an unpleasant emotion that arises in response to perception, perceived dangers or threats. Fear causes physiological and psychological changes. It may produce behavioral reactions such as mounting an aggressive response or fleeing the ...

, whereas Europe's cooler

A cooler, portable ice chest, ice box, cool box, chilly bin (in New Zealand), or esky (Australia) is an insulated box used to keep food or drink cool.

Ice cubes are most commonly placed in it to help the contents inside stay cool. Ice packs ...

climate and fragmented geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

bred liberty and moderation

Moderation is the process or trait of eliminating, lessening, or avoiding extremes. It is used to ensure normality throughout the medium on which it is being conducted. Common uses of moderation include:

* A way of life emphasizing perfect amo ...

. He identified "intimidation

Intimidation is a behaviour and legal wrong which usually involves deterring or coercing an individual by threat of violence. It is in various jurisdictions a crime and a civil wrong (tort). Intimidation is similar to menacing, coercion, terro ...

" as the principle

A principle may relate to a fundamental truth or proposition that serves as the foundation for a system of beliefs or behavior or a chain of reasoning. They provide a guide for behavior or evaluation. A principle can make values explicit, so t ...

of despotism (rule by fear) in contrast to honor

Honour ( Commonwealth English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is a quality of a person that is of both social teaching and personal ethos, that manifests itself as a code of conduct, and has various elements such as val ...

in monarchies or virtue

A virtue () is a trait of excellence, including traits that may be morality, moral, social, or intellectual. The cultivation and refinement of virtue is held to be the "good of humanity" and thus is Value (ethics), valued as an Telos, end purpos ...

in republics. Montesquieu also linked political absolutism

Absolutism may refer to:

Government

* Absolutism (European history), period c. 1610 – c. 1789 in Europe

** Enlightened absolutism, influenced by the Enlightenment (18th- and early 19th-century Europe)

* Absolute monarchy, in which a monarch r ...

with social and cultural conditions: for example, he argued that Islam, by uniting spiritual and temporal authority, was an "ally" of despotism (though he acknowledged religion could sometimes restrain a despot by imposing moral rules).

Despite its negative judgment, Montesquieu's analysis was empirical and comparative for its time. He drew heavily on travel literature (citing sources like Bernier and Chardin) to catalogue variations in Oriental governments. For instance, he noted that Persia's succession of despotisms differed from China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

's stable bureaucratic autocracy, yet in his view both shared the essential quality of power without check. Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, in his view, was the natural home of despotism, a vast milieu where geography and history conspired to keep societies stagnant under arbitrary rule. Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, by contrast, was presented as uniquely disposed to freedom

Freedom is the power or right to speak, act, and change as one wants without hindrance or restraint. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving oneself one's own laws".

In one definition, something is "free" i ...

, though Montesquieu did warn that even European states

The list below includes all entities falling even partially under any of the regions of Europe, various common definitions of Europe, geographical or political. Fifty generally recognised sovereign states, Kosovo with limited, but substantial, ...

might lapse into despotism under certain conditions (for example, if a monarch extended his realm too far and eroded intermediate institutions, a scenario he feared in his own era). Published to great acclaim, ''Spirit of the Laws'' made Oriental despotism a standard lens through which Enlightenment Europe viewed the East. Montesquieu's influence ensured that late 18th-century political theory

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and legitimacy of political institutions, such as states. This field investigates different forms of government, ranging from d ...

assumed a basic opposition: Occident

The Occident is a term for the West, traditionally comprising anything that belongs to the Western world. It is the antonym of the term ''Orient'', referring to the Eastern world. In English, it has largely fallen into disuse. The term occidental ...

= moderate government under law, Orient

The Orient is a term referring to the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of the term ''Occident'', which refers to the Western world.

In English, it is largely a meto ...

= unchecked despotic power.

Not all ''philosophes'' agreed on the causes or even the existence of such a stark East-West divide, and the concept

A concept is an abstract idea that serves as a foundation for more concrete principles, thoughts, and beliefs.

Concepts play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied within such disciplines as linguistics, ...

sparked lively debate

Debate is a process that involves formal discourse, discussion, and oral addresses on a particular topic or collection of topics, often with a moderator and an audience. In a debate, arguments are put forward for opposing viewpoints. Historica ...

. Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

, for example, admired certain Asian civilizations and accused Montesquieu of misreading his sources

Source may refer to:

Research

* Historical document

* Historical source

* Source (intelligence) or sub source, typically a confidential provider of non open-source intelligence

* Source (journalism), a person, publication, publishing institute ...

. In a rebuttal

In law, rebuttal is a form of evidence that is presented to contradict or nullify other evidence that has been presented by an adverse party. By analogy the same term is used in politics and public affairs to refer to the informal process by w ...

, Voltaire argued that real Eastern states like Ottoman Turkey did not fit Montesquieu's caricature

A caricature is a rendered image showing the features of its subject in a simplified or exaggerated way through sketching, pencil strokes, or other artistic drawings (compare to: cartoon). Caricatures can be either insulting or complimentary, ...

. Drawing on empirical observation

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how the ...

, he claimed there were laws and constraints in Muslim kingdoms and that Montesquieu had conjured a theoretical despotism that had no matches

A match is a tool for starting a fire. Typically, matches are made of small wooden sticks or stiff paper. One end is coated with a material that can be ignited by friction generated by striking the match against a suitable surface. Wooden matc ...

in history. Other critics with firsthand expertise bolstered this view: the orientalist Abraham-Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron, who had lived in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and Persia, published ''Législation Orientale'' (1778

Events

January–March

* January 18 – Third voyage of James Cook: Sea captain, Captain James Cook, with ships HMS Resolution (1771), HMS ''Resolution'' and HMS Discovery (1774), HMS ''Discovery'', first views Oahu, Oʻahu th ...

) to refute the notion that Oriental rulers were entirely above the law or that private property was absent in Asia. Anquetil showed, for instance, that the Mughal and Persian empires had legal codes and recognized property rights, thereby directly challenging the stereotype of an omnipotent Asiatic monarch owning everything and everyone. Such critiques were motivated not only by scholarly accuracy

Accuracy and precision are two measures of ''observational error''.

''Accuracy'' is how close a given set of measurements (observations or readings) are to their ''true value''.

''Precision'' is how close the measurements are to each other.

The ...

but also by contemporary politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

: as European colonial interests in places like India grew, there was an urgent need to understand Asian systems on their own terms, rather than dismiss them as mere despotisms. Anquetil warned that glibly labeling India despotic insulted a complex civilization, especially at a time when France and Britain were vying for influence there.

Meanwhile, other Enlightenment writers took Montesquieu's thesis in different directions. Nicolas-Antoine Boulanger's ''Recherches sur l'origine du despotisme oriental'' (1761) concurred that Asiatic despotism was real, but rooted it firmly in theocracy

Theocracy is a form of autocracy or oligarchy in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries, with executive and legislative power, who manage the government's ...

(a word coined in that work): he argued that priestly authority and "mystification" of the masses through religion were the ultimate basis of despots' power. Boulanger thus shifted emphasis away from climate and toward religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

as the engine of Oriental absolute rule, reflecting the broader anti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, ...

spirit of the Enlightenment (using "Asiatic tyranny" as a veiled critique of European churchly domination as well). Helvétius and others echoed Boulanger in doubting geography as destiny; they saw despotism as a political construct, often buttressed by superstition, rather than a simple outgrowth of environment. At the Enlightenment's end, Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; ; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French philosopher, political economist, politician, and mathematician. His ideas, including suppo ...

in his ''Sketch for a Historical Picture of Progress'' (c.1794) gave the idea a humanitarian revolutionary twist: he portrayed Orient vs. Occident in stark moral terms and urged "enlightened" European nations to emancipate the peoples subjected to Oriental despotism, whom he saw as trapped in oppression and stagnation. This was an early articulation of what would later be called the "civilizing mission

The civilizing mission (; ; ) is a political rationale for military intervention and for colonization purporting to facilitate the cultural assimilation of indigenous peoples, especially in the period from the 15th to the 20th centuries. As ...

", using the trope of despotic East to justify Western intervention as a benevolent duty.

Notably, China occupied a special place in Enlightenment discussions. The French physiocrats ( economic philosophers) admired China's agrarian bureaucracy and, rather counter-intuitively, held it up as a model of "good" despotism. François Quesnay

François Quesnay (; ; 4 June 1694 – 16 December 1774) was a French economist and physician of the Physiocratic school. He is known for publishing the " Tableau économique" (Economic Table) in 1758, which provided the foundations of the ideas ...

's essay ''Despotisme de la Chine'' (1767) argued that the Chinese emperor's rule was effectively constrained by rational laws and Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Founded by Confucius ...

moral order, making it a benevolent autocracy quite unlike the arbitrary despotisms elsewhere. The physiocrats coined the term "legal despotism

The concept of legal despotism (French language, French: ''despotisme légal'') formed part of the basis of the 18th century French physiocrats' political doctrine, developed alongside their more popularly known (in modern day) economic thought. ...

" or "despotism of evidence", suggesting that an enlightened absolute ruler following natural law could achieve social harmony and prosperity. They thus offered a rare positive re-imagining of Oriental despotism, leveraging Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

reports of China's stable governance to argue that strong central authority was not always tyrannical

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to r ...

but could be virtuous and economically beneficial. This sinophilic strand stood in contrast to Montesquieu's largely negative schema, highlighting that Enlightenment thought about the East was diverse: some saw Asia's autocrats as despised symbols of backwardness, others as exemplars of orderly

In healthcare, an orderly (also known as a ward assistant, nurse assistant or healthcare assistant) is a hospital attendant whose job consists of assisting medical and nursing staff with various nursing and medical interventions. These duties a ...

paternalistic rule.

By the late 18th century, "Oriental despotism" had become a commonplace of Western discourse, so much so that it even bounced back on Europe's own self-analysis. French critics of absolutism, during and after Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

's reign, routinely compared their king to an "Oriental despot" and France to a Persia or Turkey in bondage. Montesquieu's ''Persian Letters'' itself satirized French society through the eyes of Persian visitors, implicitly likening Louis XIV's centralized state to an oriental court. In Britain's imperial debates, too, the trope was invoked: figures like Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

lambasted misrule in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

by warning that Europeans were descending to the level of oriental despots in their treatment of Indians. As colonial administrators gained direct experience in Asia, they sometimes took the concept literally, with significant consequences: British officials in late 18th-century India, imbued with the idea that the Mughal system was one of absolutism without private land ownership, implemented reforms (such as the Permanent Settlement of Bengal

The Permanent Settlement, also known as the Permanent Settlement of Bengal, was an agreement between the East India Company and landlords of Bengal to fix revenues to be raised from land that had far-reaching consequences for both agricultural me ...

in 1793

The French Republic introduced the French Revolutionary Calendar starting with the year I.

Events

January–June

* January 7 – The Ebel riot occurs in Sweden.

* January 9 – Jean-Pierre Blanchard becomes the first to ...

) to create secure property rights, hoping to remedy "oriental" defects. This policy of treating zamindars

A zamindar in the Indian subcontinent was an autonomous or semi-autonomous feudal lord of a ''zamindari'' (feudal estate). The term itself came into use during the Mughal Empire, when Persian was the official language; ''zamindar'' is th ...

(revenue landlords) as English-style proprietors was a direct application of Enlightenment political theory, and it backfired, causing economic disruption and social dislocation. The episode vividly demonstrated how the European idea of Oriental despotism, when imposed as a template on Eastern societies, could misjudge native institutions and produce unintended results. Thus by 1800 the concept was not merely academic: it underpinned real strategies of governance and justified both liberal reforms

The Liberal welfare reforms (1906–1914) were a series of acts of social legislation passed by the Liberal Party after the 1906 general election. They represent the Liberal Party's transition rejecting the old laissez faire policies and enacting ...

and imperial domination in the non-Western world.

19th-century evolutionary frameworks and Marxist theory

Around the turn of the 19th century, the notion of Oriental despotism was absorbed into new grand theories of historical development. Enlightenment universalism gave way toevolutionary

Evolution is the change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, resulting in certa ...

or stadial thinking, and many writers placed despotism as an early stage in humanity's political progression. Late Enlightenment and German Idealist

German idealism is a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary ...

philosophers, such as Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

, J. G. Herder

Johann Gottfried von Herder ( ; ; 25 August 174418 December 1803) was a Prussian philosopher, theologian, pastor, poet, and literary critic. Herder is associated with the Age of Enlightenment, ''Sturm und Drang'', and Weimar Classicism. He was ...

, and above all G. W. F. Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

, repackaged the East-West dichotomy in a developmental schema. Kant, for example, described some Asian states (like China) as static despotic regimes and voiced a growing Sinophobia

Anti-Chinese sentiment (also referred to as Sinophobia) is the fear or dislike of Chinese people or Chinese culture.

It is frequently directed at Overseas Chinese, Chinese minorities which live outside Greater China and it involves immigratio ...

in German thought, suggesting that China's supposedly unchanging absolutism illustrated a lack of progress. Herder associated the predominance of agriculture and settled village life in Asia with political stagnation and despotism, implying that societies pass through an "agricultural despotic" phase before higher forms of civic freedom emerge. These ideas fed into Hegel's influential philosophy of history

Philosophy of history is the philosophy, philosophical study of history and its academic discipline, discipline. The term was coined by the French philosopher Voltaire.

In contemporary philosophy a distinction has developed between the ''specul ...

(lectured 1820s), which placed "Oriental despotism" as the starting point of world-historical development. Hegel taught that the Oriental world was the "childhood of history": the first stage in the evolution of Spirit (Geist

''Geist'' () is a German noun with a significant degree of importance in German philosophy. ''Geist'' can be roughly translated into three English meanings: ghost (as in the supernatural entity), spirit (as in the Holy Spirit), and mind or int ...

), where only one person (the emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

or sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

) is truly free and the rest have no individual autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

. In Hegel's dialectic

Dialectic (; ), also known as the dialectical method, refers originally to dialogue between people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to arrive at the truth through reasoned argument. Dialectic resembles debate, but the c ...

, history is the story of freedom gradually expanding, and in the Orient this process had barely begun. Despotic Asia, he argued, represented a society just out of the state of nature but not yet aware of personal rights; it was a homogeneous mass ruled by an absolute will. The consequence was political immobility: Hegel asserted that Eastern empires (China, India, Persia, etc.) were essentially static and extraneous to the true "development of Spirit," which moved westward to Greece, Rome, and ultimately the Germanic (European) world. "The History of the World travels from East to West," Hegel declared, for Europe is the end of history: the Orient, lacking internal dynamism, remained stuck in time. This schema reinforced an "inexorable connection between despotism and immobility", giving a philosophical

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

rationale to the earlier Enlightenment judgment that Asia was fundamentally different and inferior in political terms. Hegel's prestige helped to canonize the idea that Oriental despotism implies absence of historical progress, a view that dovetailed with 19th-century imperial ideology (the White Man's Burden

"The White Man's Burden" (1899), by Rudyard Kipling, is a poem about the Philippine–American War (1899–1902) that exhorts the United States to assume colonial control of the Filipino people and their country.''

In "The White Man's Burden ...

to bring progress to the stagnant East) and with European justifications of their global dominance.

The most significant adaptation of the concept in the 19th century came from the realm of political economy and Marxist theory

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Western Marxism, which drew f ...

. Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, while initially influenced by Hegel's constructs, reinterpreted Oriental despotism in materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism according to which matter is the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materia ...

terms as part of his theory of the " Asiatic mode of production." Writing in the 1850s about India and China, Marx picked up long-noted features, such as the absence of private landownership and the village-based agrarian economy

An agrarian society, or agricultural society, is any community whose economy is based on producing and maintaining crops and farmland. Another way to define an agrarian society is by seeing how much of a nation's total production is in agricultur ...

, and argued these formed a distinct socioeconomic system

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyses wh ...

. In Marx's analysis, Oriental despotism was rooted in economic structure: because land was traditionally owned by the sovereign (or the community) rather than individuals, and villages were largely self-sufficient, a powerful centralized state was needed to coordinate large public works (especially irrigation) and to extract surplus from an otherwise stagnant rural society. This "Asiatic mode of production", characterized by communal villages, hydraulic agriculture, and state ownership of property, created a stable but stagnant social order. For Marx, it explained why great Asian civilizations had not undergone the same class-driven revolutions as Europe's and had remained frozen in a "primitive" phase of history. He explicitly linked the idea to despotism: the oriental mode of production, Marx wrote, was the material foundation that made an all-powerful despotic state both possible and necessary, fusing economic and political absolutism. This was essentially a secular, structural restatement of Montesquieu's old observation about irrigation and central power. Marx's prime examples were India and China, but he also extended the logic to "parts of Russia" and the Islamic world. In Marx's view, Asian despotic regimes, though often stable for centuries, represented a historical dead-end: a "block" to human progress that would eventually be shattered by external forces. Famously, Marx saw British colonial rule in India as performing a "double mission": it was violently destroying the stagnant Asiatic order, but in doing so it would lay the groundwork for a modern society and integration into capitalist progress. This judgment that colonialism, however brutal, was indirectly enabling India's regeneration out of Oriental despotism, illustrates how deeply the concept had permeated 19th-century

The 19th century began on 1 January 1801 (represented by the Roman numerals MDCCCI), and ended on 31 December 1900 (MCM). It was the 9th century of the 2nd millennium. It was characterized by vast social upheaval. Slavery was abolished in ...

European thought, even among its radical

Radical (from Latin: ', root) may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Classical radicalism, the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and Latin America in the 19th century

*Radical politics ...

critics. Marx's formulation spurred extensive debate within socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

circles and academia

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

, as it implied a unique path of development

Development or developing may refer to:

Arts

*Development (music), the process by which thematic material is reshaped

* Photographic development

*Filmmaking, development phase, including finance and budgeting

* Development hell, when a proje ...

for Eastern societies. In late 19th-century Russia, for instance, intellectuals fiercely discussed whether their own Tsarist

Tsarist autocracy (), also called Tsarism, was an autocracy, a form of absolute monarchy in the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire. In it, the Tsar possessed in principle authority and ...

autocracy was an "Asiatic" despotism following an Asiatic mode of production or a feudal monarchy

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

that could evolve like Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

. Russian "Westernizers" often invoked the concept to disparage Tsarism as a holdover of Mongol-style absolutism that must be overcome, while Slavophiles rejected that label, arguing Russia had its own distinct tradition. Thus, the Western concept of Oriental despotism was not only projected onto Russia by foreigners but was also actively contested within Russian thought, showing the term's provocative reach. Similarly, in the Ottoman Empire's late 19th-century reform era, some Ottoman intellectuals strove to counter European depictions of the Sultanate as hopelessly despotic, by highlighting constitutional moves and Islamic legal restraints that moderated the monarch's power. The idea of Oriental despotism became a yardstick in global political discourse: either a stigma to escape or a diagnosis to be embraced in calls for reform.

Weber, Wittfogel, and Cold War revival

Entering the 20th century, academic interest in "Oriental despotism" waned somewhat associal science

Social science (often rendered in the plural as the social sciences) is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among members within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the ...

developed more nuanced frameworks. Yet key thinkers continued to revisit the idea, particularly in the context of explaining why the West industrialized and modernized while the East (supposedly) did not. Max Weber

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German Sociology, sociologist, historian, jurist, and political economy, political economist who was one of the central figures in the development of sociology and the social sc ...

, the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

sociologist, integrated the concept into his comparative studies of civilization. Weber analyzed ancient economies and argued that environmental and structural factors made Near Eastern and Asian societies develop powerful bureaucratic states that stifled individualism, unlike the city-states and feudal polities of Europe. Echoing older theories, Weber highlighted irrigation as a prime cause: in regions like Pharaonic Egypt or Mesopotamia, the need for large-scale water control led to centralized administrations and a "hydraulic bureaucracy" overseeing canals and flood management. "The crucial factor which made Near Eastern development so different was the need for irrigation systems," Weber wrote, which "demanded the existence of a unified bureaucracy". The result, in Weber's assessment, was the "subjugation of the individual" in Eastern cultures, whereas the Mediterranean world (Greece, in particular) benefited from a freer social environment and a purely secular civic life that enabled the rise of capitalism. He pointed to the patrimonial bureaucracy of Imperial China, characterized by a cadre of officials personally dependent on the emperor, as a model case where a tradition of centralized administration impeded the growth of autonomous cities, merchant classes, or legal-rational authority. Weber gave new scholarly respectability to the idea that Oriental political structures were inherently anti-progressive. By tying political forms to economic rationality, he supported the "European miracle" narrative: a unique combination of factors allowed the West to escape the trap of agrarian despotism and achieve modern capitalism. Weber's work thus revitalized the core notion of Oriental despotism in early 20th-century social science, helping frame the long history of Eastern polities as a contrast case that underscored European singularity.

It was not until the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

era, however, that "Oriental despotism" as a term made a dramatic comeback, and this was largely due to Karl August Wittfogel

Karl August Wittfogel (; 6 September 1896 – 25 May 1988) was a German-American playwright, historian, and sinologist. He was originally a Marxist and an active member of the Communist Party of Germany, but after the Second World War, he was ...

. Wittfogel was a German-American historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human species; as well as the ...

who in 1957 published '' Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power'', the most famous modern work dedicated to the concept. Himself a former Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

, Wittfogel broke with orthodox Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

-friendly Marxism and used the idea of Oriental despotism as a weapon to criticize contemporary communist states. In this sweeping study, he built upon Marx and Weber to argue that " hydraulic civilizations" (societies dependent on large-scale irrigation and water works) tended to develop authoritarian bureaucratic governments he dubbed "oriental despotisms". According to Wittfogel's "hydraulic hypothesis," the technical requirements of managing irrigation in arid or flood-prone regions (like Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China) led to the rise of an all-powerful centralized state apparatus; that bureaucracy, in turn, amassed control over both economy and society, resulting in totalitarian control of a kind unknown in the decentralized West. Wittfogel essentially formalized the idea of a distinctive non-Western path of civilization: unlike the feudal-to-capitalist trajectory of Europe, the Orient followed a "hydraulic-bureaucratic" path culminating in stagnant absolutist empires. He not only surveyed ancient Asian empires but provocatively argued that modern Communist regimes in China and the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

were new incarnations of Oriental despotism. In his view, Marx had been shortsighted to see socialism as a leap forward. Wittfogel claimed the Communist Party-state under Stalin or Mao was structurally akin to the old despotic dynasties, simply with "industrial" means. He described Soviet Russia as a "monocentric" system akin to Asiatic monarchy, in contrast to the "polycentric" pluralism of Western societies. This thesis, arriving at the height of the Cold War, fed into the ideological narrative that communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

represented an Asiatic-like tyranny antithetical to Western freedom.

Wittfogel's ''Oriental Despotism'' was both influential and controversial. Supporters praised its grand comparative sweep and the insight that environmental adaptation (irrigation) could shape political evolution. His work drew explicitly from the lineage of Montesquieu, Marx, and Weber, tying together climate, economic mode of production, and bureaucratic form into one grand explanation. However, many scholars, especially sinologists

Sinology, also referred to as China studies, is a subfield of area studies or East Asian studies involved in social sciences and humanities research on China. It is an academic discipline that focuses on the study of the Chinese civilization ...

and anthropologists

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

, criticized Wittfogel's claims as overly deterministic and empirically flawed. For example, Chinese history experts pointed out that not all major waterworks in China were state-run, that private property and local institutions did exist to significant degrees, and that the term "despotism" oversimplified the complex legal and moral restraints on imperial power. Historian Frederick W. Mote in 1961 famously attacked Wittfogel's thesis as misreading Chinese history, arguing that the growth of Chinese imperial power was not unchecked or unchanging and that the term "despotism" is a dubious fit for traditional Chinese rule. Likewise, British scientist-historian Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, initia ...

, in reviewing Wittfogel, objected that applying a derogatory word like despotism, freighted with Western notions of arbitrary tyranny, distorted our understanding of how Confucian bureaucratic governance actually worked. These critiques were part of a broader mid-20th-century reassessment that warned against uncritical use of the old Orientalist tropes. Nonetheless, Wittfogel's book had a significant impact, especially outside of Asian studies. It kept alive the idea that there was a through-line from ancient Eastern empires to modern totalitarian states: an East-West divide in political culture that resonated with the geopolitics of the 1950s. Wittfogel's revival of "Oriental despotism" demonstrated the enduring allure of this historical concept, even as it was now being adapted to very contemporary debates about freedom and tyranny.

Modern critiques and reframing

By the late 20th century, the concept of Oriental despotism came under sustained attack from new intellectual currents, notably post-colonial studies and revisionist historiography. Scholars in these fields argued that "Oriental despotism" was less a neutral analytical model and more a Eurocentric myth that said more about Western self-justification than about Asian realities. In his landmark 1978 book ''Orientalism

In art history, literature, and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world (or "Orient") by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. Orientalist painting, particularly of the Middle ...

'', Edward Said

Edward Wadie Said (1 November 1935 – 24 September 2003) was a Palestinian-American academic, literary critic, and political activist. As a professor of literature at Columbia University, he was among the founders of Postcolonialism, post-co ...

identified the trope of the "Oriental despot" as a key element of Western imaginings of the East: a stereotype of "the arbitrary power of Asiatic princes" used to portray Eastern societies as stagnant, cruel, and inferior. Said and those influenced by him showed how this image had served as an ideological tool of colonial domination, rationalizing European imperial rule as bringing law and liberty to benighted peoples. From Montesquieu's climate theories to Marx's evolutionary schema and Wittfogel's Cold War polemic, the through-line was a claim of Western superiority and Eastern backwardness. Modern scholarship has been intent on deconstructing these claims. Researchers have highlighted, for example, the constitutional and consultative traditions within Ottoman and Mughal governance, or the civic institutions in Qing China

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the Ming dynasty ...

, which contradict the caricature of entirely unchecked tyranny. They note that terms like "despot" were often pejorative labels affixed by outsiders rather than accepted descriptions by insiders.

In regions once dubbed "oriental despotisms," local reformers and intellectuals had long contested the characterization. In the 19th century, Asian and Middle Eastern thinkers increasingly engaged with Western political ideas and offered their own perspectives: Ottoman constitutionalists argued the Sultan's power should be limited by shari'a and a parliament (hardly a concession to being "natural despots"), Indian nationalists pointed out that pre-colonial India had village self-governance and traditions of consultation, and Chinese reformers in the late Qing and Republican eras strove to show that China could modernize its monarchy or establish a republic, escaping the "Oriental despotic" mold that Westerners ascribed to it. These indigenous debates underscore that "Oriental despotism" was never a self-image, but a contentious external judgment: one that those so labeled often resisted or sought to disprove.

Within Western academia, the late 20th century brought a more critical historiography. Influenced by the " global history" and post-colonial turns, scholars argue that the concept's theoretical force has essentially vanished today. Comparative historians have moved away from rigid East-West dichotomies and instead emphasize economic and cultural connections, indigenous agency, and the diversity of political forms in Asia. For instance, economic historian B. J. O'Leary (1989) revisited the Marxian debates on the Asiatic mode and found them wanting, suggesting that Indian history did not fit a unilinear despotic model and that colonialism's impact was more complex. Area specialists continue to dismantle monolithic notions: Ottoman studies

Ottoman studies is an interdisciplinary branch of the humanities that addresses the history, culture, costumes, religion, art, such as literature and music, science, economy, and politics of the Ottoman Empire. It is a sub-category of Oriental stu ...

reveal a negotiated system of provincial governance and law (far from an omnipotent Sultan free of constraints), while Sinology

Sinology, also referred to as China studies, is a subfield of area studies or East Asian studies involved in social sciences and humanities research on China. It is an academic discipline that focuses on the study of the Chinese civilization p ...

has shown that Qing emperors operated within a framework of Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Founded by Confucius ...

norms and had to earn the "Mandate of Heaven

The Mandate of Heaven ( zh, t=天命, p=Tiānmìng, w=, l=Heaven's command) is a Chinese ideology#Political ideologies, political ideology that was used in History of China#Ancient China, Ancient China and Chinese Empire, Imperial China to legit ...

" by just rule: concepts incompatible with pure arbitrary despotism. Furthermore, anthropologists studying irrigation-based communities found that "hydraulic societies" did not always lead to centralization: small-scale local management was often the norm, undermining Wittfogel's deterministic link between water and authoritarianism.

At the same time, some modern analysts caution that in dismissing "Oriental despotism" entirely, one should not ignore the real patterns of authoritarian governance in many historical Asian states. There remains debate on how to balance recognizing Orientalism's exaggerations with acknowledging that, for example, the Chinese imperial state or Mughal state were more centralized and autocratic in certain respects than contemporaneous European polities. Critics of Said have argued he downplayed the genuine history and function of despotism as a regime type by focusing solely on Western representations. They point out that concepts akin to "despotism" existed in Asian political thought too (for example, Chinese political theory condemned "bao jun" 暴君 (tyrannical rulers) and praised enlightened monarchs who ruled by moral law). Thus the scholarly conversation has shifted to a more nuanced ground: moving beyond the simplistic East-vs-West trope, researchers examine each society's own political idioms and power structures. The term "Oriental despotism" itself, however, is now mostly used in historical context, as an object of study (how and why Western thinkers conceived this idea) rather than as a reliable analytic category.

See also

*Asian values

Asian values is a political ideology that attempts to define elements of society, culture and history common to the nations of Southeast and East Asia, particularly values of commonality and collectivism for social unity and economic good — c ...

* Asiatic mode of production

* Hydraulic empire

A hydraulic empire, also known as a hydraulic despotism, hydraulic society, hydraulic civilization, or water monopoly empire, is a social or government structure which maintains power and control through exclusive control over access to water. I ...

* Tsarist absolutism

References

{{Reflist Orientalism Government in Asia