Arthur Bliss on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

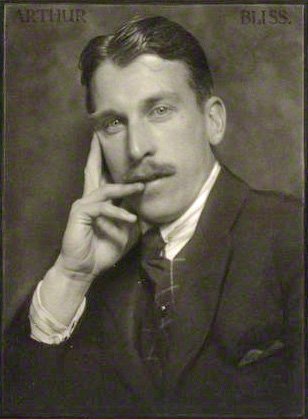

Sir Arthur Edward Drummond Bliss (2 August 189127 March 1975) was an English composer and conductor.

Bliss's musical training was cut short by the First World War, in which he served with distinction in the army. In the post-war years he quickly became known as an unconventional and

Sir Arthur Edward Drummond Bliss (2 August 189127 March 1975) was an English composer and conductor.

Bliss's musical training was cut short by the First World War, in which he served with distinction in the army. In the post-war years he quickly became known as an unconventional and

"Bliss, Sir Arthur Edward Drummond (1891–1975)".

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, October 2009, accessed 21 March 2011 Agnes Bliss died in 1895, and the boys were brought up by their father, who instilled in them a love for the arts. Bliss was educated at Bilton Grange preparatory school, Rugby and

"Bliss, Sir Arthur."

''Grove Music Online'', Oxford Music Online; accessed 21 March 2011. Bliss graduated in classics and music in 1913 and then studied at the

"From Rebel to Romantic: The Music of Arthur Bliss".

''The Musical Times'', August 1991, pp. 383–386; accessed 21 March 2011 When the First World War broke out, Bliss joined the army, and fought in France as an officer in the

"Arthur Bliss".

'' From the mid-1920s onwards Bliss moved more into the established English musical tradition, leaving behind the influence of Stravinsky and the French modernists, and in the words of the critic Frank Howes, "after early enthusiastic flirtations with aggressive modernism admitted to a romantic heart and asgiven rein to its less and less inhibited promptings"Howes, Frank, "Sir Arthur Bliss – A modern romantic",'' The Times'', 27 April 1956, p. 3 He wrote two major works with American orchestras in mind, the'' Introduction and Allegro'' (1926), dedicated to the

From the mid-1920s onwards Bliss moved more into the established English musical tradition, leaving behind the influence of Stravinsky and the French modernists, and in the words of the critic Frank Howes, "after early enthusiastic flirtations with aggressive modernism admitted to a romantic heart and asgiven rein to its less and less inhibited promptings"Howes, Frank, "Sir Arthur Bliss – A modern romantic",'' The Times'', 27 April 1956, p. 3 He wrote two major works with American orchestras in mind, the'' Introduction and Allegro'' (1926), dedicated to the

"Aspects of Bliss".

''The Musical Times'', August 1971, pp. 743–745; accessed 21 March 2011 His last large-scale work of the 1930s was his

''Who Was Who'', A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edition, Oxford University Press, December 2007, accessed 21 March 2011 He composed more film music, and two ballets, '' Miracle in the Gorbals'' (1944), and '' Adam Zero'' (1946). In 1948, Bliss turned his attention to opera, with '' The Olympians''. He and the novelist and playwright J. B. Priestley had been friends for many years, and they agreed to collaborate on an opera, despite their lack of any operatic experience. Priestley's libretto was based on a legend that "the pagan deities, robbed of their divinity, became a troupe of itinerant players, wandering down the centuries".Priestley, J. B

"My Friend Bliss"

''The Musical Times'', August 1971, pp. 740–741, accessed 22 March 2011 The opera portrays the confusion that results when the actors unexpectedly find themselves restored to deity. The opera opened the 1949–50

In addition to his official functions, Bliss continued to compose steadily throughout the 1950s. His works from that decade include his Second String Quartet (1950); a scena, ''The Enchantress'' (1951), for the

In addition to his official functions, Bliss continued to compose steadily throughout the 1950s. His works from that decade include his Second String Quartet (1950); a scena, ''The Enchantress'' (1951), for the

Texts and translations of vocal music by Arthur Bliss

a

the LiederNet ArchiveThe Arthur Bliss society

*

Leicestershire Schools Symphony Orchestra websiteReview

of Cello Concerto

Arthur Bliss @ Boosey & Hawkes"Music from the Western Front"

performance by Chamber Domaine, which includes the Bliss Piano Quartet in A from 1915, given at

Sir Arthur Edward Drummond Bliss (2 August 189127 March 1975) was an English composer and conductor.

Bliss's musical training was cut short by the First World War, in which he served with distinction in the army. In the post-war years he quickly became known as an unconventional and

Sir Arthur Edward Drummond Bliss (2 August 189127 March 1975) was an English composer and conductor.

Bliss's musical training was cut short by the First World War, in which he served with distinction in the army. In the post-war years he quickly became known as an unconventional and modernist

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

composer, but within the decade he began to display a more traditional and romantic side in his music. In the 1920s and 1930s he composed extensively not only for the concert hall, but also for films and ballet.

In the Second World War, Bliss returned to England from the US to work for the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

and became its director of music. After the war he resumed his work as a composer, and was appointed Master of the Queen's Music

Master of the King's Music (or Master of the Queen's Music, or earlier Master of the King's Musick) is a post in the Royal Household of the United Kingdom. The holder of the post originally served the Kingdom of England, monarch of England, dire ...

.

In Bliss's later years, his work was respected but was thought old-fashioned, and it was eclipsed by the music of younger colleagues such as William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton (29 March 19028 March 1983) was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera. His best-known works include ''Façade'', the cantat ...

and Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten of Aldeburgh (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, o ...

. Since his death, his compositions have been well represented in recordings, and many of his better-known works remain in the repertoire of British orchestras.

Biography

Early years

Bliss was born in Barnes, a London suburb now, but then in Surrey, the eldest of three sons of Francis Edward Bliss (1847–1930), a businessman fromMassachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

, and his second wife, Agnes Kennard ''née'' Davis (1858–1895).Burn, Andrew"Bliss, Sir Arthur Edward Drummond (1891–1975)".

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, October 2009, accessed 21 March 2011 Agnes Bliss died in 1895, and the boys were brought up by their father, who instilled in them a love for the arts. Bliss was educated at Bilton Grange preparatory school, Rugby and

Pembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college is the third-oldest college of the university and has over 700 students and fellows. It is one of the university's larger colleges, with buildings from ...

, where he studied classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

, but also took lessons in music from Charles Wood. Other influences on him during his Cambridge days were Edward Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

, whose music made a lasting impression on him, and E.J. Dent.Cole, Hugo and Andrew Burn"Bliss, Sir Arthur."

''Grove Music Online'', Oxford Music Online; accessed 21 March 2011. Bliss graduated in classics and music in 1913 and then studied at the

Royal College of Music

The Royal College of Music (RCM) is a conservatoire established by royal charter in 1882, located in South Kensington, London, UK. It offers training from the undergraduate to the doctoral level in all aspects of Western Music including pe ...

in London for a year. At the RCM he found his composition tutor, Sir Charles Stanford, of little help to him, but found inspiration from Ralph Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams ( ; 12 October 1872– 26 August 1958) was an English composer. His works include operas, ballets, chamber music, secular and religious vocal pieces and orchestral compositions including nine symphonies, written over ...

and Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst (born Gustavus Theodore von Holst; 21 September 1874 – 25 May 1934) was an English composer, arranger and teacher. Best known for his orchestral suite ''The Planets'', he composed many other works across a range ...

and his fellow-students, Herbert Howells

Herbert Norman Howells (17 October 1892 – 23 February 1983) was an English composer, organist, and teacher, most famous for his large output of Anglican church music.

Life

Background and early education

Howells was born in Lydney, Gloucest ...

, Eugene Goossens and Arthur Benjamin

Arthur Leslie Benjamin (18 September 1893 in Sydney – 10 April 1960 in London) was an Australian composer, pianist, conductor and teacher. He is best known as the composer of ''Jamaican Rumba'' (1938) and of the '' Storm Clouds Cantata'', fea ...

.Obituary, ''The Times'', 29 March 1975, p. 14

In his brief time at the college, he got to know the music of the Second Viennese School

The Second Viennese School () was the group of composers that comprised Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils, particularly Alban Berg and Anton Webern, and close associates in early 20th-century Vienna. Their music was initially characterized by late ...

and the repertory of Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), also known as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, patron, ballet impresario a ...

's ''Ballets Russes

The Ballets Russes () was an itinerant ballet company begun in Paris that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. The company never performed in Russia, where the Russian Revolution, Revolution ...

'', with music by modern composers such as Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

, Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism in music, Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composer ...

and Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky ( – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer and conductor with French citizenship (from 1934) and American citizenship (from 1945). He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of ...

.Burn, Andrew"From Rebel to Romantic: The Music of Arthur Bliss".

''The Musical Times'', August 1991, pp. 383–386; accessed 21 March 2011 When the First World War broke out, Bliss joined the army, and fought in France as an officer in the

Royal Fusiliers

The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in continuous existence for 283 years. It was known as the 7th Regiment of Foot until the Childers Reforms of 1881.

The regiment served in many war ...

until 1917 and then in the Grenadier Guards

The Grenadier Guards (GREN GDS) is the most senior infantry regiment of the British Army, being at the top of the Infantry Order of Precedence. It can trace its lineage back to 1656 when Lord Wentworth's Regiment was raised in Bruges to protect ...

for the rest of the war. His bravery earned him a mention in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

, and he was twice wounded and once gassed.

His younger brother, Kennard, was killed in the war, and his death affected Bliss deeply. The music scholar Byron Adams writes, "Despite the apparent heartiness and equilibrium of the composer's public persona, the emotional wounds inflicted by the war were deep and lasting."Adams, Byron. "Bliss on Music", ''Notes'', December 1992), pp. 586–588; accessed 22 March 2011 In 1918, Bliss converted to Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

.

Early compositions

Although he had begun composing while still a schoolboy, Bliss later suppressed all hisjuvenilia

Juvenilia are literary, musical or artistic works produced by authors during their youth. Written juvenilia, if published at all, usually appear as retrospective publications, some time after the author has become well known for later works. Bac ...

, and, with the single exception of his 1916 ''Pastoral'' for clarinet and piano, reckoned the 1918 work ''Madam Noy'' as his first official composition. With the return of peace, his career took off rapidly as a composer of what were, for British audiences, startlingly new pieces, often for unusual ensembles, strongly influenced by Ravel, Stravinsky and the young French composers of Les Six

"Les Six" () is a name given to a group of six composers, five of them French and one Swiss, who lived and worked in Montparnasse. The name has its origins in two 1920 articles by critic Henri Collet in '' Comœdia'' (see Bibliography). Their mu ...

. Among these are a concerto for wordless tenor voice, piano and strings (1920), and ''Rout'' for wordless soprano and chamber ensemble (subsequently revised for orchestra), which received a double encore at its first performance.

In 1919, he arranged incidental music from Elizabethan sources for ''As You Like It

''As You Like It'' is a pastoral Shakespearean comedy, comedy by William Shakespeare believed to have been written in 1599 and first published in the First Folio in 1623. The play's first performance is uncertain, though a performance at Wil ...

'' at Stratford-on-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon ( ), commonly known as Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is situated on the River Avon, north-west of ...

, and conducted a series of Sunday concerts at Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith

The Lyric Theatre, also known as the Lyric Hammersmith, is a nonprofit theatre on Lyric Square, off King Street, Hammersmith, London."About the Lyric" > "History" ''Lyric'' official website. Retrieved January 2024.

Background

The Lyric Theatre ...

, where he also conducted Pergolesi's opera ''La serva padrona

''La serva padrona'' (''The Maid Turned Mistress'') is a 1733 intermezzo by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710–1736) to a libretto by Gennaro Federico, after the Play (theatre), play by Jacopo Angello Nelli. It is some 40 minutes long, in two par ...

.'' Viola Tree

Viola Tree (17 July 1884 – 15 November 1938) was an English actress, singer, playwright and author. Daughter of the actor Herbert Beerbohm Tree, she made many of her early appearances with his company at Her Majesty's Theatre, His Majesty's Th ...

's production of ''The Tempest

''The Tempest'' is a Shakespeare's plays, play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1610–1611, and thought to be one of the last plays that he wrote alone. After the first scene, which takes place on a ship at sea during a tempest, th ...

'' at the Aldwych Theatre

The Aldwych Theatre is a West End theatre, located in Aldwych in the City of Westminster, central London. It was listed Grade II on 20 July 1971. Its seating capacity is 1,200 on three levels.

History

Origins

The theatre was constructed in th ...

in 1921, interspersed incidental music by Thomas Arne

Thomas Augustine Arne (; 12 March 17105 March 1778) was an English composer. He is best known for his patriotic song " Rule, Britannia!" and the song " A-Hunting We Will Go", the latter composed for a 1777 production of '' The Beggar's Opera'', w ...

and Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

, with new music by Bliss for an ensemble of male voices, piano, trumpet, trombone, gongs and five percussionists dispersed through the theatre.Evans, Edwin"Arthur Bliss".

''

The Musical Times

''The Musical Times'' was an academic journal of classical music edited and produced in the United Kingdom.

It was originally created by Joseph Mainzer in 1842 as ''Mainzer's Musical Times and Singing Circular'', but in 1844 he sold it to Alfr ...

'', February 1923, pp. 95–99, accessed 21 March 2011

''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' wrote that "Bliss was acquiring a reputation as a tearaway" by the time he was commissioned, through Elgar's influence, to write a large-scale symphonic work ('' A Colour Symphony'') for the Three Choirs Festival

200px, Worcester cathedral

200px, Gloucester cathedral

The Three Choirs Festival is a music festival held annually at the end of July, rotating among the cathedrals of the Three Counties (Hereford, Gloucester, and Worcester) and originally fe ...

of 1922. The work was well received; in ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', Samuel Langford

Samuel Langford (1863 - 8 May 1927) was an influential English music critic of the early twentieth century.

Trained as a pianist, Langford became chief music critic of ''The Manchester Guardian'' in 1906, serving in that post until his death. ...

called Bliss "far and away the cleverest writer among the English composers of our time"; ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' praised it highly (though doubting whether much was gained by the designation of the four movements as purple, red, blue and green) and commented that the symphony confirmed Bliss's transition from youthful experimenter to serious composer. After the third performance of the work, at the Queen's Hall

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect Thomas Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. Fro ...

under Sir Henry Wood, ''The Times'' wrote, "Continually changing patterns scintillate … till one is hypnotised by the ingenuity of the thing." Elgar, who attended the first performance, complained that the work was "disconcertingly modern."

In 1923 Bliss's father, who had remarried, decided to retire in the US. He and his wife settled in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

. Bliss went with them and remained there for two years, working as a conductor, lecturer, pianist and occasional critic. While there he met Gertrude "Trudy" Hoffmann (1904–2008), youngest daughter of Ralph

Ralph (pronounced or ) is a male name of English origin, derived from the Old English ''Rædwulf'' and Old High German ''Radulf'', cognate with the Old Norse ''Raðulfr'' (''rað'' "counsel" and ''ulfr'' "wolf").

The most common forms are:

* Ra ...

and Gertrude Hoffmann. They were married in 1925. The marriage was happy and lasted for the rest of Bliss's life; there were two daughters. Soon after the marriage, Bliss and his wife moved to England.

From the mid-1920s onwards Bliss moved more into the established English musical tradition, leaving behind the influence of Stravinsky and the French modernists, and in the words of the critic Frank Howes, "after early enthusiastic flirtations with aggressive modernism admitted to a romantic heart and asgiven rein to its less and less inhibited promptings"Howes, Frank, "Sir Arthur Bliss – A modern romantic",'' The Times'', 27 April 1956, p. 3 He wrote two major works with American orchestras in mind, the'' Introduction and Allegro'' (1926), dedicated to the

From the mid-1920s onwards Bliss moved more into the established English musical tradition, leaving behind the influence of Stravinsky and the French modernists, and in the words of the critic Frank Howes, "after early enthusiastic flirtations with aggressive modernism admitted to a romantic heart and asgiven rein to its less and less inhibited promptings"Howes, Frank, "Sir Arthur Bliss – A modern romantic",'' The Times'', 27 April 1956, p. 3 He wrote two major works with American orchestras in mind, the'' Introduction and Allegro'' (1926), dedicated to the Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphia Orchestra is an American symphony orchestra, based in Philadelphia. One of the " Big Five" American orchestras, the orchestra is based at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, where it performs its subscription concerts, n ...

and Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British-born American conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra. H ...

, and ''Hymn to Apollo'' (1926) for the Boston Symphony

The Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) is an American orchestra based in Boston. It is the second-oldest of the five major American symphony orchestras commonly referred to as the " Big Five". Founded by Henry Lee Higginson in 1881, the BSO perfor ...

and Pierre Monteux

Pierre Benjamin Monteux (; 4 April 18751 July 1964) was a French (later American) conductor. After violin and viola studies, and a decade as an orchestral player and occasional conductor, he began to receive regular conducting engagements in 1 ...

.

Bliss began the 1930s with ''Pastoral'' (1930). In the same year he wrote '' Morning Heroes'', a work for narrator, chorus and orchestra, written in the hope of exorcising the spectre of the First World War: "Although the war had been over for more than ten years, I was still troubled by frequent nightmares; they all took the same form. I was still there in the trenches with a few men; we knew the armistice had been signed, but we had been forgotten; so had a section of the Germans opposite. It was as though we were both doomed to fight on till extinction. I used to wake with horror."

During the decade Bliss wrote chamber works for leading soloists including a Clarinet Quintet for Frederick Thurston (1932) and a Viola Sonata for Lionel Tertis

Lionel Tertis, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE (29 December 187622 February 1975) was an English viola, violist. He was one of the first viola players to achieve international fame, and a noted teacher.

Career

Tertis was born ...

(1933). In 1935, in the words of the ''Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' is an encyclopedic dictionary of music and musicians. Along with the German-language '' Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'', it is one of the largest reference works on the history and th ...

'', "he firmly established his position as Elgar's natural successor with the Romantic, expansive and richly scored Music for Strings." Two dramatic works from this decade remain well known, the music for Alexander Korda

Sir Alexander Korda (; born Sándor László Kellner; ; 16 September 1893 – 23 January 1956)

's 1936 film of H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

's ''Things to Come

''Things to Come'' is a 1936 British science fiction film produced by Alexander Korda, directed by William Cameron Menzies, and written by H. G. Wells. It is a loose adaptation of Wells' book '' The Shape of Things to Come''. The film stars Ra ...

'', and a ballet score to his own scenario based on a chess game. Choreographed by Ninette de Valois

Dame Ninette de Valois (born Edris Stannus; 6 June 1898 – 8 March 2001) was an Irish-born British dancer, teacher, choreographer, and director of classical ballet. Most notably, she danced professionally with Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russ ...

, ''Checkmate

Checkmate (often shortened to mate) is any game position in chess and other chess-like games in which a player's king is in check (threatened with ) and there is no possible escape. Checkmating the opponent wins the game.

In chess, the king is ...

'' was still in the repertoire of the Royal Ballet

The Royal Ballet is a British internationally renowned classical ballet company, based at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London, England. The largest of the five major ballet companies in Great Britain, the Royal Ballet was founded ...

in 2011.

By the late 1930s, Bliss was no longer viewed as a modernist; the works of his juniors William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton (29 March 19028 March 1983) was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera. His best-known works include ''Façade'', the cantat ...

and the youthful Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten of Aldeburgh (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, o ...

were increasingly prominent, and Bliss's music began to seem old-fashioned.Palmer, Christopher"Aspects of Bliss".

''The Musical Times'', August 1971, pp. 743–745; accessed 21 March 2011 His last large-scale work of the 1930s was his

Piano Concerto

A piano concerto, a type of concerto, is a solo composition in the classical music genre which is composed for piano accompanied by an orchestra or other large ensemble. Piano concertos are typically virtuosic showpieces which require an advance ...

, composed for the pianist Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

, who gave the world premiere at the World's Fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition, is a large global exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specific site for a perio ...

in New York in June 1939. Bliss and his family attended the performance and then stayed on in the US for a holiday. While they were there, the Second World War broke out. Bliss initially stayed in America, teaching at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

. He felt impelled to return to England to do what he could for the war effort, and in 1941, leaving his wife and children in California, he made the hazardous Atlantic crossing.

1940s

At first, Bliss found little useful work to do in England. He joined theBBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

's overseas music service in May 1941, but was plainly under-employed. He suggested to Sir Adrian Boult

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult, CH (; 8 April 1889 – 22 February 1983) was a British conductor. Brought up in a prosperous mercantile family, he followed musical studies in England and at Leipzig, Germany, with early conducting work in London ...

, who was at that time both the chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBC SO) is a British orchestra based in London. Founded in 1930, it was the first permanent salaried orchestra in London, and is the only one of the city's five major symphony orchestras not to be self-governing. The ...

and the BBC's director of music, that Boult should step down in his favour from the latter post. Bliss wrote to his wife: "I want more power as I have a lot to give which my comparatively minor post does not allow me to use fully."Kennedy, p. 195 Boult agreed to the proposal, which freed him to concentrate on conducting. Bliss served as director of music at the BBC from 1942 to 1944, laying the foundations for the launch of the Third Programme

The BBC Third Programme was a national radio station produced and broadcast from 1946 until 1967, when it was replaced by BBC Radio 3. It first went on the air on 29 September 1946 and became one of the leading cultural and intellectual forces ...

after the war. During the war, he also served on the music committee of the British Council

The British Council is a British organisation specialising in international cultural and educational opportunities. It works in over 100 countries: promoting a wider knowledge of the United Kingdom and the English language (and the Welsh lang ...

together with Vaughan Williams and William Walton.

In 1944, when Bliss's family returned from the US, he resigned from the BBC and returned to composing, having written nothing since his String Quartet in 1941."Bliss, Sir Arthur"''Who Was Who'', A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edition, Oxford University Press, December 2007, accessed 21 March 2011 He composed more film music, and two ballets, '' Miracle in the Gorbals'' (1944), and '' Adam Zero'' (1946). In 1948, Bliss turned his attention to opera, with '' The Olympians''. He and the novelist and playwright J. B. Priestley had been friends for many years, and they agreed to collaborate on an opera, despite their lack of any operatic experience. Priestley's libretto was based on a legend that "the pagan deities, robbed of their divinity, became a troupe of itinerant players, wandering down the centuries".Priestley, J. B

"My Friend Bliss"

''The Musical Times'', August 1971, pp. 740–741, accessed 22 March 2011 The opera portrays the confusion that results when the actors unexpectedly find themselves restored to deity. The opera opened the 1949–50

Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

season. It was directed by Peter Brook

Peter Stephen Paul Brook (21 March 1925 – 2 July 2022) was an English theatre and film director. He worked first in England, from 1945 at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, from 1947 at the Royal Opera House, and from 1962 for the Royal Shak ...

, with choreography by Frederick Ashton

Sir Frederick William Mallandaine Ashton (17 September 190418 August 1988) was a British ballet dancer and choreographer. He also worked as a director and choreographer in opera, film and revue.

Determined to be a dancer despite the oppositio ...

. The doyen of English music critics, Ernest Newman

Ernest Newman (30 November 1868 – 7 July 1959) was an English music critic and musicologist. ''Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' describes him as "the most celebrated British music critic in the first half of the 20th century." His ...

, praised it highly: "here is a composer with real talent for opera ... in Mr. Priestley he has been fortunate enough to find an English Boito", but generally it received a polite rather than a rapturous reception. Priestley attributed this to the failure of the conductor, Karl Rankl

Karl Rankl (1 October 1898 – 6 September 1968) was a British conductor and composer who was of Austrian birth. A pupil of the composers Schoenberg and Webern, he conducted at opera houses in Austria, Germany and Czechoslovakia until fleeing f ...

, to learn the music or to cooperate with Brook, and to lack of rehearsal of the last act. The critics attributed it to Priestley's inexperience as an opera librettist, and to the occasional lack of "the soaring tune for the human voice" in Bliss's music."The Royal Opera – 'The Olympians'", ''The Times'', 30 September 1949, p. 6; Hope-Wallace, Philip, "The Olympians", ''The Manchester Guardian'', 30 September 1949, p. 5; and Blom, Eric, "Priestley for Bliss", ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. First published in 1791, it is the world's oldest Sunday newspaper.

In 1993 it was acquired by Guardian Media Group Limited, and operated as a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' ...

'' 2 October 1949, p. 6 After the Covent Garden run of ten performances,Haltrecht, p. 132 the company presented the work in Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, but did not revive it in subsequent years; it received a concert performance and broadcast in 1972.

Later years

In 1950, Bliss wasknighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

. After the death of Sir Arnold Bax he was appointed Master of the Queen's Music

Master of the King's Music (or Master of the Queen's Music, or earlier Master of the King's Musick) is a post in the Royal Household of the United Kingdom. The holder of the post originally served the Kingdom of England, monarch of England, dire ...

in 1953, to the relief of Walton, who feared he would be asked to take the post. In ''The Times'', Howes commented, "The duties of a Master of the Queen's Music are what he chooses to make of them, but they include the composition of ceremonial and occasional music". Bliss, who composed quickly and with facility, was able to discharge the many duties of the post, providing music as required for state occasions, from the birth of a child to the Queen, to the funeral of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, to the investiture of the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

. Howes commended Bliss's ''Processional'' for the 1953 coronation, and ''A Song of Welcome'', Bliss's first official ''pièce d'occasion''.

In 1956, Bliss headed the first delegation by British musicians to the Soviet Union since the end of the Second World War. The party included the violinist Alfredo Campoli, the oboist Léon Goossens, the soprano Jennifer Vyvyan, the conductor Clarence Raybould

Robert Clarence Raybould (28 June 1886 – 27 March 1972) was an English conductor, pianist and composer who conducted works ranging from musical comedy and operetta, Gilbert and Sullivan to the standard classical repertoire. He also champione ...

and the pianist Gerald Moore

Gerald Moore (30 July 1899 – 13 March 1987) was an English classical pianist best known for his career as a collaborative pianist for many distinguished musicians. Among those with whom he was closely associated were Dietrich Fischer-Diesk ...

. Bliss returned to Moscow in 1958, as a member of the jury of the International Tchaikovsky Competition

The International Tchaikovsky Competition is a classical music competition held every four years in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, Russia, for pianists, violinists, and cellists between 16 and 32 years of age and singers between 19 and 32 years of ...

, with fellow jurors including Emil Gilels

Emil Grigoryevich Gilels (19 October 191614 October 1985, born Samuil) was a Soviet pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time. His sister Elizabeth, three years his junior, was a violinist. His daughter Elena ...

and Sviatoslav Richter

Sviatoslav Teofilovich Richter ( – August 1, 1997) was a Soviet and Russian classical pianist. He is regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time,Great Pianists of the 20th Century and has been praised for the "depth of his interpreta ...

.

In addition to his official functions, Bliss continued to compose steadily throughout the 1950s. His works from that decade include his Second String Quartet (1950); a scena, ''The Enchantress'' (1951), for the

In addition to his official functions, Bliss continued to compose steadily throughout the 1950s. His works from that decade include his Second String Quartet (1950); a scena, ''The Enchantress'' (1951), for the contralto

A contralto () is a classical music, classical female singing human voice, voice whose vocal range is the lowest of their voice type, voice types.

The contralto's vocal range is fairly rare, similar to the mezzo-soprano, and almost identical to ...

Kathleen Ferrier

Kathleen Mary Ferrier (22 April 19128 October 1953) was an English contralto singer who achieved an international reputation as a stage, concert and recording artist, with a repertoire extending from folksong and popular ballads to the class ...

; a Piano Sonata (1952); and a Violin Concerto (1955), for Campoli. The orchestral ''Meditations on a Theme by John Blow'' (1955) was a particularly deep-felt work, and Bliss regarded it highly among his output. In 1959–60 he collaborated with the librettist Christopher Hassall on an opera for television, based on the scriptural story of Tobias and the Angel . It won praise for the way in which Bliss and Hassall had understood and adapted to the more intimate medium of television, though some critics thought Bliss's music competent but unremarkable.

In 1961, Bliss and Hassall collaborated on a cantata

A cantata (; ; literally "sung", past participle feminine singular of the Italian language, Italian verb ''cantare'', "to sing") is a vocal music, vocal Musical composition, composition with an musical instrument, instrumental accompaniment, ty ...

, ''The Beatitudes'', commissioned for the opening of the new Coventry Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Saint Michael, commonly known as Coventry Cathedral, is the seat of the Bishop of Coventry and the Diocese of Coventry within the Church of England. The cathedral is located in Coventry, West Midlands (county), West Midla ...

. Reviews were friendly, but the work has rarely been performed since, and has been eclipsed by another choral work written for Coventry at the same time, Britten's ''War Requiem

The ''War Requiem'', Op. 66, is a choral and orchestral composition by Benjamin Britten, composed mostly in 1961 and completed in January 1962. The ''War Requiem'' was performed for the consecration of the new Coventry Cathedral, in the Englis ...

''. Bliss followed this with two further large-scale choral works, ''Mary of Magdala'' (1962) and ''The Golden Cantata'' (1963).

Throughout his life, Bliss was vigilant on the state of music in Britain, about which he had written extensively since the 1920s. In 1969 he publicly censured the BBC for its plan to cut its classical music budget and disband several of its orchestras. He was delegated by his colleagues Walton, Britten, Peter Maxwell Davies

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies (8 September 1934 – 14 March 2016) was an English composer and conductor, who in 2004 was made Master of the Queen's Music.

As a student at both the University of Manchester and the Royal Manchester College of Music ...

and Richard Rodney Bennett

Sir Richard Rodney Bennett (29 March 193624 December 2012) was an English composer and pianist. He was noted for his musical versatility, drawing from such sources as jazz, romanticism, and avant-garde; and for his use of twelve-tone technique ...

to make a strong protest to William Glock

Sir William Frederick Glock, CBE (3 May 190828 June 2000) was a British music critic and musical administrator who was instrumental in introducing the Continental avant-garde, notably promoting the career of Pierre Boulez.

Biography

Glock was b ...

, the BBC's controller of music.

Bliss continued to compose into his eighth and ninth decades, in which his works included the Cello Concerto (1970) for Mstislav Rostropovich

Mstislav Leopoldovich Rostropovich (27 March 192727 April 2007) was a Russian Cello, cellist and conducting, conductor. In addition to his interpretations and technique, he was well known for both inspiring and commissioning new works, which enl ...

, the ''Metamorphic Variations'' for orchestra (1972), and a final cantata, ''Shield of Faith'' (1974), for soprano, baritone, chorus and organ, celebrating 500 years of St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, setting poems chosen from each of the five centuries of the chapel's existence.

Bliss died at his London home in 1975 at the age of 83. His wife Trudy outlived him by 33 years, dying in 2008 at the age of 104.

Music

Early works

The musicologist Christopher Palmer was censorious of those who sought to characterise Bliss's music as "an early tendency to ''enfant terribilisme'' yielding very quickly to a compromise with the Establishment and a perpetuating of the Elgar tradition". Nonetheless, as a young man Bliss was certainly regarded as ''avant garde''. ''Madam Noy'', a "witchery" song, was first performed in June 1920. The lyric is by an anonymous author, and the setting is for soprano with flute, clarinet, bassoon, harp, viola, and bass. In a 1923 study of Bliss, Edwin Evans wrote that the piquant instrumental background to the gruesome story established the direction that Bliss was to take. The second Chamber Rhapsody (1919) is "an idyllic work for soprano, tenor, flute, cor anglais, and bass, the two voices vocalising on 'Ah' throughout, and being placed as instruments in the ensemble." Bliss contrasted the pastoral tone of that work with ''Rout'' (1920) an uproarious piece for soprano and instrumental ensemble; " the music conveys an impression such as one might gather at an open window at carnival time … the singer is given a series of meaningless syllables chosen for their phonetic effect". In his next work, ''Conversations'' for violin, viola, cello, flute and oboe (1921), Bliss chose a deliberately prosaic subject. It consists of five sections, entitled "Committee Meeting," "In the Wood," "In the Ball-room," "Soliloquy," and "In the Tube at Oxford Circus." Evans wrote of this work that although the instrumentation is ingenious, "much of heinterest ispolyphonic

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice ( monophony) or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords ...

, especially in the first and last numbers."

Bliss followed these works with three compositions for larger forces, a Concerto (1920) and Two Orchestral Studies (1920). The Concerto, for piano, voice and orchestra, was experimental, and Bliss later revised it, removing the vocal part. The ''Melée Fantasque'' (1921) showed Bliss's skill in writing glittering orchestration.

Mature works

Of Bliss's early works, ''Rout'' is occasionally performed, and has been recorded, but the first of his works to enter the repertoire (at least in the UK) is the ''Colour Symphony''. Each of the four movements represents a colour: "purple, the colour of amethysts, pageantry, royalty, and death; red, the colour of rubies, wine, revelry, furnaces, courage, and magic; blue, the colour of sapphires, deep water, skies, loyalty, and melancholy; and green, the colour of emeralds, hope, joy, youth, spring, and victory." The first and third are slow movements, the second a scherzo, and the fourth fugal, described by the Bliss specialist Andrew Burn as "a compositional tour de force, a superbly constructed double fugue, the initial subject slow and angular for strings, gradually becoming an Elgarian ceremonial march, the second a bubbling theme for winds."Burn, Andrew (2006). Notes to Chandos CD CHAN 10380 Burn observes that in three works written soon after his marriage, the Oboe Quintet (1927), ''Pastoral'' (1929) and ''Serenade'' (1929), "Bliss's voice assumed the mantle of maturity … all are imbued with a quality of contentment reflecting his serenity." Of the works of Bliss's maturity, Burn comments that many of them were inspired by external stimuli. Some by the performers for whom they were written, such as the concertos forpiano

A piano is a keyboard instrument that produces sound when its keys are depressed, activating an Action (music), action mechanism where hammers strike String (music), strings. Modern pianos have a row of 88 black and white keys, tuned to a c ...

(1938), violin (1955) and cello (1970); some by literary and theatrical partners, such as the film music, ballets, cantatas and ''The Olympians''; some by painters, such as the ''Serenade'' and the ''Metamorphic Variations''; some by classical literature, such as ''Hymn to Apollo'' (1926), ''The Enchantress'', and ''Pastoral''. Of Bliss's works after the Second World War, his opera, ''The Olympians'' is generally considered a failure. The idiom was judged to be old-fashioned. A contemporary critic, in a broadly favourable review, wrote, "Bliss has wisely cleared his idiom of modern harmonic astringency. He uses quite a lot of common chords and progressions; in fact, he has gone back to the harmony of the musical gods. The result, inevitably, is a certain air of reminiscence."

Among the late works, the Cello Concerto is one of the more frequently played. When its dedicatee, Rostropovich, gave the first performance at the 1970 Aldeburgh Festival

The Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts is an English arts festival devoted mainly to classical music. It takes place each June in the town of Aldeburgh, Suffolk and is centred on Snape Maltings Concert Hall.

History of the Aldeburgh Festi ...

, Britten, who conducted the performance, regarded it as a major work and persuaded Bliss to change its title from "Concertino" to "Concerto". It is an approachable piece of which Bliss said "There are no problems for the listener – only for the soloist".

Both Palmer and Burn comment on a sinister vein that sometimes breaks out in Bliss's music, in passages such as the Interlude "Through the valley of the shadow of Death" in ''The Meditations on a Theme of John Blow'', and the orchestral introduction to ''The Beatitudes''. In Burn's words, such moments can be profoundly disquieting. Palmer comments that the musical forerunner of such passages is probably "the extraordinary spectral march-like irruption" in the Scherzo of Elgar's Second Symphony.

In a centenary assessment of Bliss's music, Burn singles out for mention "the youthful vigour of ''A Colour Symphony''", "the poignant humanity of '' Morning Heroes''", "the romantic lyricism of the Clarinet Quintet", "the drama of ''Checkmate'', ''Miracle in the Gorbals'' and ''Things to Come''", and "the spiritual probing of the ''Meditations on a Theme of John Blow'' and ''Shield of Faith''." Other works of Bliss classed by Palmer as among the finest are the ''Introduction and Allegro'', the ''Music for Strings'', the Oboe Quintet, ''A Knot of Riddles'' and ''the Golden Cantata.''

Honours, legacy and reputation

In addition to hisknighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

, Bliss was appointed KCVO (1969) and CH (1971). He received honorary degrees from the universities of Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, Lancaster

Lancaster may refer to:

Lands and titles

*The County Palatine of Lancaster, a synonym for Lancashire

*Duchy of Lancaster, one of only two British royal duchies

*Duke of Lancaster

*Earl of Lancaster

*House of Lancaster, a British royal dynasty

...

, and London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, as well as from Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

. The London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

appointed him its honorary President in 1958. In 1963, he received the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

.

Bliss's archive is kept at Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University Library is the main research library of the University of Cambridge. It is the largest of over 100 libraries Libraries of the University of Cambridge, within the university. The library is a major scholarly resource for me ...

. There is an Arthur Bliss Road in Newport, an Arthur Bliss Gardens in Cheltenham and a block of flats, Sir Arthur Bliss Court, in Mitcham

Mitcham is an area within the London Borough of Merton in South London, England. It is centred southwest of Charing Cross. Originally a village in the county of Surrey, today it is mainly a residential suburb, and includes Mitcham Common. It ...

, South London.

The Arthur Bliss Society was founded in 2003 to further the knowledge and appreciation of Bliss's music. The society's website includes listings of forthcoming performances of Bliss's works; in March 2011 the following works were listed as scheduled for performance in the UK and U.S.: ''Ceremonial Prelude''; Clarinet Quartet (2 performances); Four Songs for Voice, Violin and Piano; ''Music for Strings''; ''Pastoral (Lie strewn the white flocks)''; ''Royal Fanfares''; ''Seven American Poems''; String Quartet No. 2 (5 performances); ''Things to Come'' Suite (2 performances); ''Things to Come'' March.

Many of Bliss's works have been recorded. He was a capable conductor, and was in charge of some of the recordings. The Library of Cambridge University maintains a complete Bliss discography. In March 2011 it contained details of 281 recordings: 120 orchestral, 56 chamber and instrumental, 58 choral and vocal, and 47 stage and screen works. Among the works that have received multiple recordings are ''A Colour Symphony'' (6 recordings); the Cello Concerto (6); the Piano Concerto (6); ''Music for Strings'' (7); the Oboe Quintet (7); the Viola Sonata (The violin sonata was first recorded in 2010) (7); and ''Checkmate'' (complete ballet and ballet suite (9)).

On receiving the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society in 1963, Bliss said, "I don't claim to have done more than light a small taper at the shrine of music. I do not upbraid Fate for not having given me greater gifts. Endeavour has been the joy".Bliss (1991), p. 209 A hundred years after Bliss's birth, Byron Adams wrote,

See also

*Color symbolism

Color symbolism in art, literature, and anthropology is the use of color as a symbol in various cultures and in storytelling. There is great diversity in the use of colors and their associations between cultures and even within the same culture i ...

Notes and references

;Notes ;ReferencesSources

* * * * * * *External links

Texts and translations of vocal music by Arthur Bliss

a

the LiederNet Archive

*

Leicestershire Schools Symphony Orchestra website

of Cello Concerto

Arthur Bliss @ Boosey & Hawkes

performance by Chamber Domaine, which includes the Bliss Piano Quartet in A from 1915, given at

Gresham College

Gresham College is an institution of higher learning located at Barnard's Inn Hall off Holborn in Central London, England that does not accept students or award degrees. It was founded in 1597 under the Will (law), will of Sir Thomas Gresham, ...

, 26 September 2007 (available as an MP3 or MP4 download, as well as a text file).

*

*

Videos

* A short video of the Leicestershire Schools Symphony Orchestra conducted by Eric Pinkett. * Played on the piano by Sir Arthur Bliss ''Girl in a Broken Mirror'' A documentary featuring the ballet ''The Lady of Shalott'' performed by school pupils from Leicestershire and the LSSO conducted by Eric Pinkett. * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bliss, Arthur 1891 births 1975 deaths Military personnel from the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames 20th-century English classical composers 20th-century English male musicians British ballet composers English male classical composers Brass band composers Composers awarded knighthoods Masters of the Queen's Music Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists Alumni of the Royal College of Music Composers for piano British Army personnel of World War I Grenadier Guards officers Royal Fusiliers officers Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Knights Commander of the Royal Victorian Order Knights Bachelor People educated at Rugby School People educated at Bilton Grange Pupils of Charles Villiers Stanford BBC music executives People from Barnes, London Presidents of the London Symphony Orchestra English male film score composers