Arnold Beckman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Arnold Orville Beckman (April 10, 1900 – May 18, 2004) was an American chemist, inventor, investor, and philanthropist. While a professor at

Beckman was born in

Beckman was born in

At the same time that Beckman was approached about infrared spectrometry, he was contacted by Paul Rosenberg. Rosenberg worked at MIT's

At the same time that Beckman was approached about infrared spectrometry, he was contacted by Paul Rosenberg. Rosenberg worked at MIT's

Beckman also saw that computers and automation offered a myriad of opportunities for integration into instruments, and the development of new instruments. Beckman Instruments purchased Berkeley Scientific Company in the 1950s, and later developed a Systems Division within

Beckman also saw that computers and automation offered a myriad of opportunities for integration into instruments, and the development of new instruments. Beckman Instruments purchased Berkeley Scientific Company in the 1950s, and later developed a Systems Division within

File:Beckman Auditorium.JPG, Beckman Auditorium, California Institute of Technology

File:Beckman Ceiling.jpg, Ceiling of Beckman Auditorium, specially designed for its acoustic properties

File:Reflecting Beckman Institute, Caltech.jpg, Beckman Institute at Caltech, reflected in water

File:BeckmanInstitute.jpg, Beckman Institute at University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign

File:Beckman Conference Center, National Academies (USA).JPG, Beckman Conference Center, National Academies

Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation

*

Beckman Coulter

company website

Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation

philanthropic foundation website

Arnold O. Beckman Legacy Project

Chemical Descent Tree for Arnold Orville Beckman

from th

Chemical Genealogy Database

of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Department of Chemistry

Arnold O. Beckman High School

website

Beckman Historical Collection

(Digitized corporate records of Beckman Coulter, Incorporated, as well as personal papers of American scientist and industrialist Arnold Orville Beckman)

Guide to the Arnold O. Beckman Papers

Caltech Archives, California Institute of Technology

Interview with Arnold O. Beckman

Caltech Oral Histories {{DEFAULTSORT:Beckman, Arnold O. 1900 births 2004 deaths 20th-century American inventors American men centenarians American chairpersons of corporations American investors American manufacturing businesspeople American nonprofit businesspeople Philanthropists from Illinois American physical chemists American technology chief executives American technology company founders Businesspeople from California Businesspeople from Illinois California Institute of Technology alumni California Institute of Technology faculty Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences National Medal of Science laureates National Medal of Technology recipients University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign alumni Presidential Citizens Medal recipients American scientific instrument makers Silicon Valley people People from Corona, California People from La Jolla, San Diego People from Newport Beach, California People from Livingston County, Illinois People from Altadena, California 20th-century American businesspeople 20th-century American philanthropists Delta Upsilon members

California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech) is a private research university in Pasadena, California, United States. The university is responsible for many modern scientific advancements and is among a small group of institutes ...

, he founded Beckman Instruments

Beckman Coulter, Inc. is a Danaher Corporation company that develops, manufactures, and markets products relevant to biomedical testing. It operates in the industries of diagnostics under the brand name Beckman Coulter and life sciences under t ...

based on his 1934 invention of the pH meter

A pH meter is a scientific instrument that measures the hydrogen-ion activity in water-based solutions, indicating its acidity or alkalinity expressed as pH. The pH meter measures the difference in electrical potential between a pH electro ...

, a device for measuring acidity (and alkalinity), later considered to have "revolutionized the study of chemistry and biology". He also developed the DU spectrophotometer, "probably the most important instrument ever developed towards the advancement of bioscience". Beckman funded the Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory

Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory, later known as Shockley Transistor Corporation, was a pioneering semiconductor developer founded by William Shockley, and funded by Beckman Instruments, Inc., in 1955. It was the first high technology compan ...

, the first silicon transistor

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to amplify or switch electrical signals and power. It is one of the basic building blocks of modern electronics. It is composed of semiconductor material, usually with at least three terminals f ...

company in California, thus giving rise to Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley is a region in Northern California that is a global center for high technology and innovation. Located in the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area, it corresponds roughly to the geographical area of the Santa Clara Valley ...

. In 1965, he retired as president of Beckman Instruments, instead becoming the chairman of its board of directors. On November 23, 1981, he agreed to sell the company, which was then merged with SmithKline

GSK plc (an acronym from its former name GlaxoSmithKline plc) is a British multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company with headquarters in London. It was established in 2000 by a merger of Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham, wh ...

to form SmithKline Beckman. After retirement, he and his wife Mabel (1900–1989) were numbered among the top philanthropists in the United States.

Early life

Beckman was born in

Beckman was born in Cullom, Illinois

Cullom is a village in Livingston County, Illinois, United States. Cullom is situated twenty miles east of Pontiac which is the county seat, and is one mile west of the Ford County line. The population was 555 at the 2010 census.

History

Cul ...

, a village of about 500 people in a farming community. He was the youngest son of George Beckman, a blacksmith, and his second wife Elizabeth Ellen Jewkes. He was curious about the world from an early age. When he was nine, Beckman found an 1868 chemistry textbook, Joel Dorman Steele

Joel Dorman Steele (May 14, 1836 – May 25, 1886) was an American educator. He and his wife Esther Baker Steele were important textbook writers of their period, on subjects including American history, chemistry, human physiology, physics, as ...

's ''Fourteen Weeks in Chemistry'', and began trying out the experiments. His father encouraged his scientific interests by letting him convert a toolshed into a laboratory.

Beckman's mother, Elizabeth, died of diabetes in 1912. Beckman's father sold his blacksmith shop, and became a travelling salesman for blacksmithing tools and materials. A housekeeper, Hattie Lange, was engaged to look after the Beckman children. Arnold Beckman earned money as a "practice pianist" with a local band, and as an "official cream tester" running a centrifuge for a local store.

In 1914, the Beckman family moved to Normal, located just north of Bloomington, Illinois

Bloomington is a city in McLean County, Illinois, United States, and its county seat. The 2020 United States census, 2020 census showed the city had a population of 78,680, making it the List of municipalities in Illinois, 13th-most populous ci ...

, so that the young Beckmans could attend University High School in Normal, a "laboratory school" associated with Illinois State University

Illinois State University (ISU) is a public research university in Normal, Illinois, United States. It was founded in 1857 as Illinois State Normal University and is the oldest public university in Illinois. The university emphasizes teachin ...

. In 1915 they moved to Bloomington itself, but continued to attend University High, where Arnold Beckman obtained permission to take university level classes from professor of chemistry Howard W. Adams. While still in high school, Arnold started his own business, "Bloomington Research Laboratories", doing analytic chemistry for the local gas company. He also performed at night as a movie-house pianist, and played with local dance bands. He graduated valedictorian of his class, with an average of 89.41 over four years, the highest attained.

Beckman was allowed to leave school a few months early to contribute to the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

effort in early 1918 by working as a chemist. At Keystone Steel and Iron he took samples of molten iron and tested them to see if the chemical composition of carbon, sulfur, manganese and phosphorus was suitable for pouring steel.

When Beckman turned 18 in August 1918, he enlisted in the United States Marines

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines or simply the Marines, is the Marines, maritime land force service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for conducting expedi ...

. After three months at marine boot camp on Parris Island, South Carolina

Parris Island is a district of the city of Port Royal, South Carolina on an island of the same name. It became part of the city with the annexation of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island on October 11, 2002. For statistical purposes, ...

, he was sent to the Brooklyn Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York (state), New York, U.S. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a se ...

, for transit to the war in Europe. Because of a train delay, another unit embarked in place of Beckman's unit. Then, counted into groups in the barracks, Beckman missed being sent to Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

by one space in line. Instead, Arnold spent Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in October and November in the United States, Canada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Germany. It is also observed in the Australian territory ...

at the local YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organisation based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It has nearly 90,000 staff, some 920,000 volunteers and 12,000 branches w ...

, where he met 17-year-old Mabel Stone Meinzer, who was helping to serve the meal. Mabel would become his wife. A few days later, the armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

was signed, ending the war.

University education

Beckman attended theUniversity of Illinois Urbana–Champaign

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC, U of I, Illinois, or University of Illinois) is a public land-grant research university in the Champaign–Urbana metropolitan area, Illinois, United States. Established in 1867, it is the fo ...

beginning in the fall of 1918. During his freshman year, he worked with Carl Shipp Marvel

Carl Shipp "Speed" Marvel (September 11, 1894 – January 4, 1988) was an American chemist who specialized in polymer chemistry. He made important contributions to U.S. synthetic rubber program during World War II, and later worked at developing ...

on the synthesis of organic mercury compounds, but both men became ill from exposure to toxic mercury. As a result, Beckman changed his major from organic chemistry to physical chemistry, where he worked with Worth Rodebush, T. A. White, and Gerhard Dietrichson. He earned his bachelor's

A bachelor's degree (from Medieval Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six years ( ...

degree in chemical engineering in 1922 and his master's degree in physical chemistry in 1923. For his master's degree he studied the thermodynamics of aqueous ammonia solutions, a subject introduced to him by T. A. White.

Soon after arriving at the University of Illinois, Beckman joined the Delta Upsilon

Delta Upsilon (), commonly known as DU, is a collegiate men's fraternity founded on November 4, 1834, at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. It is the sixth-oldest, all-male, college Greek-letter organization founded in North America ...

fraternity. He was initiated into Zeta chapter of Alpha Chi Sigma

Alpha Chi Sigma () is a professional fraternity specializing in the fields of the chemical sciences. It has both collegiate and professional chapters throughout the United States consisting of both men and women and numbering more than 78,000 m ...

, the chemistry fraternity, in 1921 and the Gamma Alpha Graduate Scientific Fraternity in December 1922.

Beckman decided to go to California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech) is a private research university in Pasadena, California, United States. The university is responsible for many modern scientific advancements and is among a small group of institutes ...

(Caltech) for his doctorate. He stayed there for a year, before returning to New York to be near his fiancée, Mabel, who was working as a secretary for the Equitable Life Assurance Society. He found a job with Western Electric

Western Electric Co., Inc. was an American electrical engineering and manufacturing company that operated from 1869 to 1996. A subsidiary of the AT&T Corporation for most of its lifespan, Western Electric was the primary manufacturer, supplier, ...

's engineering department, the precursor to the Bell Telephone Laboratories

Nokia Bell Labs, commonly referred to as ''Bell Labs'', is an American industrial research and development company owned by Finnish technology company Nokia. With headquarters located in Murray Hill, New Jersey, Murray Hill, New Jersey, the compa ...

. Working with Walter A. Shewhart

Walter Andrew Shewhart (pronounced like "shoe-heart";

March 18, 1891 – March 11, 1967) was an American physicist, engineer and statistician. He is sometimes also known as the ''grandfather of Statistical process control, statistical quality con ...

, Beckman developed quality control

Quality control (QC) is a process by which entities review the quality of all factors involved in production. ISO 9000 defines quality control as "a part of quality management focused on fulfilling quality requirements".

This approach plac ...

programs for the manufacture of vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

s and learned about circuit design. It was here that Beckman discovered his interest in electronics

Electronics is a scientific and engineering discipline that studies and applies the principles of physics to design, create, and operate devices that manipulate electrons and other Electric charge, electrically charged particles. It is a subfield ...

.

The couple married June 10, 1925and moved back to California in 1926, where Beckman resumed his studies at Caltech. He became interested in ultraviolet photolysis and worked with his doctoral advisor, Roscoe G. Dickinson, on an instrument to find the energy of ultraviolet light. It worked by shining the ultraviolet light onto a thermocouple

A thermocouple, also known as a "thermoelectrical thermometer", is an electrical device consisting of two dissimilar electrical conductors forming an electrical junction. A thermocouple produces a temperature-dependent voltage as a result of the ...

, converting the incident heat into electricity, which drove a galvanometer

A galvanometer is an electromechanical measuring instrument for electric current. Early galvanometers were uncalibrated, but improved versions, called ammeters, were calibrated and could measure the flow of current more precisely. Galvanomet ...

. After receiving a Ph.D. in photochemistry in 1928 for this application of quantum theory to chemical reactions, Beckman was asked to stay on at Caltech as an instructor and then as a professor. Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling ( ; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist and peace activist. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. ''New Scientist'' called him one of the 20 gre ...

, another of Roscoe G. Dickinson's graduate students, was also asked to stay on at Caltech.

Relationship with Caltech

During his time at Caltech, Beckman was active in teaching at both the introductory and advanced graduate levels. Beckman shared his expertise in glass-blowing by teaching classes in the machine shop. He also taught classes in the design and use of research instruments. Beckman dealt first-hand with the chemists' need for good instrumentation as manager of the chemistry department's instrument shop. Beckman's interest in electronics made him very popular within the chemistry department at Caltech, as he was very skilled in buildingmeasuring instruments

Instrumentation is a collective term for measuring instruments, used for indicating, measuring, and recording physical quantities. It is also a field of study about the art and science about making measurement instruments, involving the related ...

.

Over the time that he was at Caltech, the focus of the department increasingly moved towards pure science and away from chemical engineering and applied chemistry. Arthur Amos Noyes

Arthur Amos Noyes (September 13, 1866 – June 3, 1936) was an American chemist, inventor and educator, born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, son of Amos and Anna Page Noyes, née Andrews. He received a PhD in 1890 from Leipzig University under ...

, head of the chemistry division, encouraged both Beckman and chemical engineer William Lacey to be in contact with real-world engineers and chemists, and Robert Andrews Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan ( ; March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1923 "for his work on the elementary charge of electricity and on the photoelectric effect".

Millikan gradua ...

, Caltech's president, referred technical questions to Beckman from government and businesses. With their blessing, Beckman began accepting outside work as a scientific and technical consultant. He also acted as a scientific expert in legal trials.

In 1964, he accepted an offer to become chairman of the Caltech Board of Trustees, where he'd been a member since 1953.

National Inking Appliance Company

In 1934, Millikan referred I. H. Lyons from the National Postal Meter Company to Arnold Beckman. Lyons wanted a non-clogging ink so that postage could be printed by machines, instead of having clerks lick stamps. Beckman's solution was to make ink withbutyric acid

Butyric acid (; from , meaning "butter"), also known under the systematic name butanoic acid, is a straight-chain alkyl carboxylic acid with the chemical formula . It is an oily, colorless liquid with an unpleasant odor. Isobutyric acid (2-met ...

, a malodorous substance. Because of this ingredient, no manufacturer wanted to manufacture it. Beckman decided to make it himself. He started the National Inking Appliance Company, obtaining space in a garage owned by instrument maker Fred Henson and hiring two Caltech students, Robert Barton and Henry Fracker. Beckman developed and took out a couple of patents for re-inking typewriter ribbon

An ink ribbon or inked ribbon is an expendable assembly serving the function of transferring pigment to paper in various devices for impact printing. Since such assemblies were first widely used on typewriters, they were often called typewriter r ...

s, but marketing them was not successful. This was Beckman's first experience at running a company and marketing a product, and while this first product failed, Beckman repurposed the company for another product.

pH Meter

Sunkist Growers

Sunkist Growers, Incorporated, branded as Sunkist in 1909, is an American citrus growers' non-stock membership cooperative composed of over 1,000 members from California and Arizona headquartered in Valencia, California. Through 31 offices in ...

was having problems with its own manufacturing process. Lemons that were not saleable as produce were made into pectin

Pectin ( ': "congealed" and "curdled") is a heteropolysaccharide, a structural polymer contained in the primary lamella, in the middle lamella, and in the cell walls of terrestrial plants. The principal chemical component of pectin is galact ...

or citric acid

Citric acid is an organic compound with the formula . It is a Transparency and translucency, colorless Weak acid, weak organic acid. It occurs naturally in Citrus, citrus fruits. In biochemistry, it is an intermediate in the citric acid cycle, ...

, with sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless gas with a pungent smell that is responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is r ...

used as a preservative. Sunkist needed to know the acidity of the product at any given time, and the colorimetric methods then in use, such as readings from litmus paper

Litmus is a water-soluble mixture of different dyes extracted from lichens. It is often absorbed onto filter paper to produce one of the oldest forms of pH indicator, used to test materials for acidity. In an acidic medium, blue litmus pape ...

, did not work well because sulfur dioxide interfered with them. Chemist Glen Joseph at Sunkist was attempting to measure the hydrogen-ion concentration in lemon juice electrochemically, but sulfur dioxide damaged hydrogen electrodes, and non-reactive glass electrodes produced weak signals and were fragile.

Joseph approached Beckman, who proposed that instead of trying to increase the sensitivity of his measurements, he amplify his results. Beckman, familiar with glassblowing, electricity, and chemistry, suggested a design for a vacuum-tube amplifier and ended up building a working apparatus for Joseph. The glass electrode used to measure pH was placed in a grid circuit in the vacuum tube, producing an amplified signal which could then be read by an electronic meter. The prototype was so useful that Joseph requested a second unit.

Beckman saw an opportunity, and rethinking the project, decided to create a complete chemical instrument which could be easily transported and used by nonspecialists. By October 1934, he had registered patent application US Patent No. 2,058,761 for his "acidimeter", later renamed the pH meter. The Arthur H. Thomas Company, a nationally known scientific instrument dealer based in Philadelphia, was willing to try selling it. Although it was priced expensively at $195, roughly the starting monthly wage for a chemistry professor at that time, it was significantly cheaper than the estimated cost of building a comparable instrument from individual components, about $500. The original pH meter weighed in at nearly 7 kg, but was a substantial improvement over a benchful of delicate equipment. The earliest meter had a design glitch, in that the pH readings changed with the depth of immersion of the electrodes, but Beckman fixed the problem by sealing the glass bulb of the electrode.

On April 8, 1935, Beckman renamed his company National Technical Laboratories

Beckman Coulter, Inc. is a Danaher Corporation company that develops, manufactures, and markets products relevant to biomedical testing. It operates in the industries of Diagnosis, diagnostics under the brand name Beckman Coulter and life science ...

, formally acknowledging his new focus on the making of scientific instruments. The company rented larger quarters at 3330 Colorado Street, and began manufacturing pH meters. The pH meter is an important device for measuring the pH of a solution, and by 11 May 1939, sales were successful enough that Beckman left Caltech to become the full-time president of National Technical Laboratories. By 1940, Beckman was able to take out a loan to build his own 12,000 square foot factory in South Pasadena.

Spectrophotometry

Ultraviolet

In 1940, the equipment needed to measure light energy in the visible spectrum could cost a laboratory as much as $3,000, a huge amount at that time. There was also growing interest in examining ultraviolet spectra beyond that range. Just as Beckman had created a single easy-to-use instrument for measuring pH, he made it a goal to create an easy-to-use instrument for spectrophotometry. Beckman's research team, led by Howard Cary, developed several models. The new spectrophotometers used a prism to separate light into its absorption spectrum and a phototube to electrically measure the light energy across the spectrum. They allowed the user to plot the light absorption spectrum of a substance, giving a standardized "fingerprint", characteristic of a compound. With Beckman's model D, later known as the DU spectrophotometer, National Technical Laboratories successfully provided the first easy-to-use single instrument containing both the optical and electronic components needed for ultraviolet-absorption spectrophotometry. The user could insert a sample, dial up the desired wavelength of light, and read the amount of absorption of that frequency from a simple meter. It produced accurate absorption spectra in both the ultraviolet and the visible regions of the spectrum with relative ease and repeatable accuracy. The National Bureau of Standards ran tests to certify that the DU's results were accurate and repeatable and recommended its use. Beckman's DU spectrophotometer has been referred to as the "model T" of scientific instruments: "This device forever simplified and streamlined chemical analysis, by allowing researchers to perform a 99.9% accurate quantitative measurement of a substance within minutes, as opposed to the weeks required previously for results of only 25% accuracy." Theodore L. Brown notes that it "revolutionized the measurement of light signals from samples". Nobel laureate Bruce Merrifield is quoted as calling the DU spectrophotometer "probably the most important instrument ever developed towards the advancement of bioscience." Development of the spectrophotometer also had direct relevance to the war effort. For example, the role of vitamins in health was being studied, and scientists wanted to identifyVitamin A

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin that is an essential nutrient. The term "vitamin A" encompasses a group of chemically related organic compounds that includes retinol, retinyl esters, and several provitamin (precursor) carotenoids, most not ...

-rich foods to keep soldiers healthy. Previous methods involved feeding rats for several weeks, then performing a biopsy to estimate Vitamin A levels. The DU spectrophotometer yielded better results in a matter of minutes. The DU spectrophotometer was also an important tool for scientists studying and producing the new wonder drug penicillin. By the end of the war, American pharmaceutical companies were producing 650 billion units of penicillin each month. Much of the work done in this area during World War II was kept secret until after the war.

Infrared

Beckman and his company were involved in a number of secret projects. There was a critical shortage ofrubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds.

Types of polyisoprene ...

, which was used in jeep and airplane tires and in tanks. Natural sources from the Far East were unavailable because of the war, and scientists sought a reliable synthetic substitute. Beckman was approached by the Office of Rubber Reserve about developing an infrared spectrophotometer to aid in the study of chemicals such as toluene

Toluene (), also known as toluol (), is a substituted aromatic hydrocarbon with the chemical formula , often abbreviated as , where Ph stands for the phenyl group. It is a colorless, water

Water is an inorganic compound with the c ...

and butadiene

1,3-Butadiene () is the organic compound with the formula CH2=CH-CH=CH2. It is a colorless gas that is easily condensed to a liquid. It is important industrially as a precursor to synthetic rubber. The molecule can be viewed as the union of two ...

. The Office of Rubber Reserve met secretly in Detroit with Robert Brattain of the Shell Development Company, Arnold O. Beckman, and R. Bowling Barnes of American Cyanamid. Beckman was asked to secretly produce a hundred infrared spectrophotometers to be used by authorized government scientists, based on a design for a single-beam spectrophotometer which had already been developed by Robert Brattain for Shell. The result was the Beckman IR-1 spectrophotometer.

By September 1942, the first of the instruments was being shipped. Approximately 75 IR-1s were made between 1942 and 1945 for use by the US synthetic-rubber effort. The researchers were not allowed to publish or discuss anything related to the new machines until after the war. Other researchers who were independently pursuing the development of infrared spectrometry, were able to publish and to develop instruments during this time without being affected by secrecy restrictions.

Beckman had continued to develop the infrared spectrophotometer after the release of the IR-1. Facing stiff competition, he decided in 1953 to go forward with a radical redesign of the instrument. The result was the IR-4, which could be operated using either a single or double beam of infrared light. This allowed a user to take both the reference measurement and the sample measurement at the same time.

Other secret projects

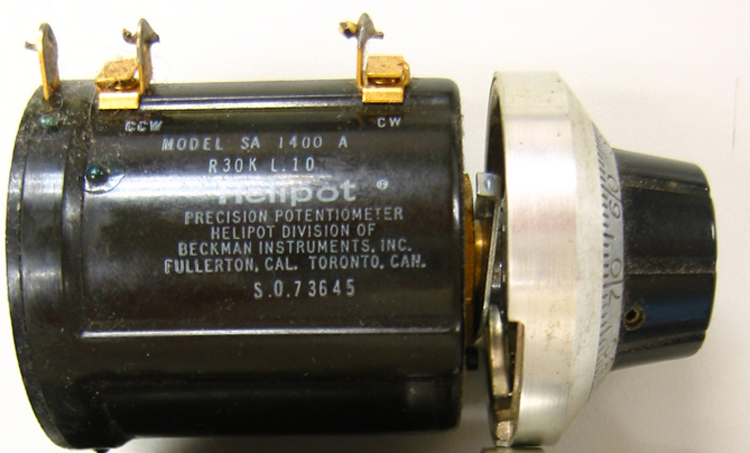

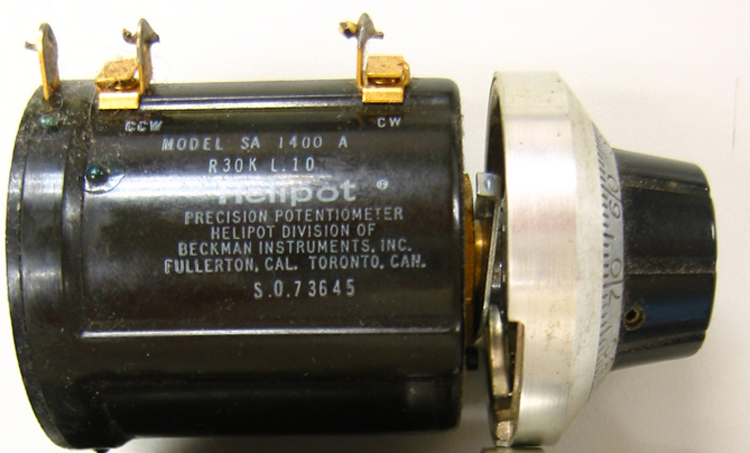

Helipot

At the same time that Beckman was approached about infrared spectrometry, he was contacted by Paul Rosenberg. Rosenberg worked at MIT's

At the same time that Beckman was approached about infrared spectrometry, he was contacted by Paul Rosenberg. Rosenberg worked at MIT's Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 3 ...

. The lab was part of a secret network of research institutions in both the United States and Britain that were working to develop radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

, "radio detecting and ranging". The project was interested in Beckman because of the high quality of the tuning knobs or "potentiometers" which were used on his pH meters. Beckman had trademarked the design of the pH meter knobs, under the name "helipot" for "helical potentiometer". Rosenberg had found that the helipot was more precise, by a factor of ten, than other knobs. Nonetheless, for use in continuously moving airplanes, ships, or submarines, which might be under attack, a redesign would be needed to ensure that the knobs could withstand shocks and vibrations.

Beckman was not allowed to tell his staff the reason behind the redesign, and they were not particularly interested in the problem; he eventually came up with a solution himself. Instead of using a wire wrapped around a coil, with pressure from a small spring to create a single contact point, he redesigned the knob to have a continuous groove, in which the contact point was contained. The contact point could then move smoothly and continuously, and could not be jarred out of contact. Beckman's model A Helipot was in tremendous demand by the military. Within the first year of its production, its sales became 40% of the company's income. Beckman spun off a separate company, the Helipot Corporation, to take on the electronics component manufactory.

Pauling oxygen meter

Linus Pauling at Caltech was also doing secret work for the military. TheNational Defense Research Committee

The National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was an organization created "to coordinate, supervise, and conduct scientific research on the problems underlying the development, production, and use of mechanisms and devices of warfare" in the U ...

called a meeting on October 3, 1940, wanting an instrument that could reliably measure oxygen content in a mixture of gases, so that they could measure oxygen conditions in submarines and airplanes. Pauling designed the Pauling oxygen meter for them. Originally approached to supply housing boxes for the meter by Holmes Sturdivant, Pauling's assistant, Beckman was soon asked to produce the entire instrument.

While the board of National Technical Laboratories was unwilling to support the secret project, whose details they could not be told, they agreed that Beckman was free to follow up on it independently. Beckman set up a second spinoff company, Arnold O. Beckman, Inc., for their manufacture. Creating the oxygen meter was a technical challenge, involving the creation of tiny, highly precise glass dumbbells. Beckman created a tiny glass-blowing machine which would generate a precisely measured puff of air to create the glass balls.

After the war, Beckman developed oxygen analyzers for another market. They were used to monitor conditions in incubators for premature babies. Doctors at Johns Hopkins University used them to determine recommendations for healthy oxygen levels for incubators.

Manhattan Project

Beckman instruments were also used by theManhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

. Scientists in the project were attempting to develop instruments to measure radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'' consisting of photons, such as radio waves, microwaves, infr ...

in gas-filled, electrically charged ionization chamber

The ionization chamber is the simplest type of gaseous ionisation detector, and is widely used for the detection and measurement of many types of ionizing radiation, including X-rays, gamma rays, alpha particles and beta particles. Conventionall ...

s in nuclear reactors. It was difficult to get reliable readings because the signals were weak. Beckman realized that with a relatively minor adjustment – substituting an input-load resistor for the glass electrode – the pH meter could be adapted to do the job. As a result, Beckman Instruments developed a new product, the micro-ammeter.

In addition, Beckman developed a dosimeter

A radiation dosimeter is a device that measures the equivalent dose, dose uptake of external ionizing radiation. It is worn by the person being monitored when used as a personal dosimeter, and is a record of the radiation dose received. Modern el ...

for measuring exposure to radiation, to protect personnel of the Manhattan project. The dosimeter was a miniature ionization chamber, charged with 170 volts. It had a small calibrated scale on top, whose needle was a platinum-covered quartz fiber. The dosimeters were also manufactured by Beckman's spinoff company, Arnold O. Beckman, Inc.

Battling smog

In postwar Southern California, including the area of Pasadena where the Beckmans lived,smog

Smog, or smoke fog, is a type of intense air pollution. The word "smog" was coined in the early 20th century, and is a portmanteau of the words ''smoke'' and ''fog'' to refer to smoky fog due to its opacity, and odour. The word was then inte ...

was becoming an increasing topic of conversation, as well as an unpleasant experience. First characterized as "gas attacks" in 1943, suspicion fell on a variety of possible causes including the smudge pot

A smudge pot (also known as a choofa or orchard heater) is an oil-burning device used to prevent frost on fruit trees. Usually a smudge pot has a large round base with a chimney coming out of the middle of the base. The smudge pot is placed bet ...

s used by orange growers, the smoke produced by local industrial plants, and car exhausts. The Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce was one of the organizations concerned about the possible causes and effects of smog, as it related both to industry (and jobs) and to quality of life in the area. Beckman was involved with the Chamber of Commerce.

In 1947, California governor Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 30th governor of California from 1943 to 1953 and as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presid ...

signed a statewide air pollution control act, authorizing the creation of Air Pollution Control Districts (APCDs) in every county of the state. The Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce asked Beckman to represent them in dealing with creation of a local APCD. The new APCD, when formed, asked Beckman to become the scientific consultant to the Air Pollution Control Officer. He held the position from 1948 to 1952.

The Air Pollution Control Officer in question was Louis McCabe, a geologist with a background in chemical engineering. McCabe initially suspected that smog was a result of sulfur dioxide pollution, and proposed that the county convert the suspected pollutant into fertilizer through a costly process. Beckman was not convinced that sulfur dioxide was the real culprit behind Los Angeles smog. He visited Gary, Indiana, where steps were being taken to address sulfur dioxide pollution, and was struck by the characteristic smell of sulfur in the air. Returning, Beckman convinced McCabe that they needed to search for a different cause.

Beckman got in touch with a Caltech professor who was working on smog, Arie Jan Haagen-Smit

Arie Jan Haagen-Smit (December 22, 1900 – March 17, 1977) was a Dutch chemist. He is best known for linking the smog in Southern California to automobiles and is therefore known by many as the "father" of air pollution control. After serving as ...

. They developed an apparatus to collect particulate matter from Los Angeles air, using a system of tubing intermittently cooled by liquid nitrogen. Haagen-Smit identified the substance they collected as a peroxy organic material. He agreed to spend a year studying the chemistry of smog. His results, presented in 1952, identified ozone and hydrocarbons from smokestacks, refineries and car exhausts as key ingredients in the formation of smog.

While Haagen-Smit worked out the genesis of smog, Beckman developed an instrument to measure it. On October 7, 1952, he was granted a patent for an "oxygen recorder" that used colorimetric methods to measure the levels of compounds present in the atmosphere. Beckman Instruments eventually developed a range of instruments for various uses in monitoring and treating automobile exhaust and air pollution. They even produced "air quality monitoring vans", customized laboratories on wheels for use by government and industry.

Beckman himself was approached by California governor Goodwin Knight

Goodwin Jess "Goodie" Knight (December 9, 1896 – May 22, 1970) was an American politician and judge who served as the 31st governor of California from 1953 to 1959. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as the 35th lieutenant ...

to head a Special Committee on Air Pollution, to propose ways to combat smog. At the end of 1953, the committee made its findings public. The "Beckman Bible" advised key steps to be taken immediately:

* stopping vapor leaks from refineries and filling stations

* establishing standards for automobile exhausts

* converting from diesel trucks and buses to propane

* asking polluting industries to restrict pollutants or move away from cities

* banning open burning of trash

* developing regional mass transportation

Beckman Instruments also acquired the Liston-Becker Instrument Company in June 1955. Founded by Max D. Liston, Liston-Becker had a successful record in the development of infrared gas analyzers. Liston developed instruments to measure smog and car exhaust emissions, essential to attempts to improve Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

air quality in the 1950s.

Beckman helped to create the Air Pollution Foundation, a non-profit organization to support research on finding solutions to smog, and educating the public about scientific issues related to smog.

In 1954, he became a member of the board of directors of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, and chairman of its Air Pollution Committee. He advocated for stronger powers for the APCD, and encouraged industry, business, and citizens to support for their work. He helped the Chamber of Commerce to develop a unified approach to monitoring smog, broadcasting smog alerts, and addressing the smog problem. On January 25, 1956, he became president of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. He identified the two key issues of his term as battling smog, and supporting the collaboration of local science, technology, industry, and education.

Beckman recognized that air quality would not improve overnight. His work with air quality continued for years, and brought him national attention. In 1967, Beckman was appointed to the Federal Air Quality Board for a four-year term, by President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

.

Electronics

John J. Murdock held substantial stock in National Technical Laboratories. He and Arnold Beckman signed a stock option agreement by which Beckman could purchase Murdock's NTL stock from his estate after his death. When Murdock died in 1948, Beckman was able to gain a controlling interest in the company. On April 27, 1950, National Technical Laboratories was renamed Beckman Instruments, Incorporated. In 1952, Beckman Instruments became a publicly traded company on the New York Curb Exchange, generating new capital for expansion, including overseas expansion.Cermets

Helipot Corporation, the spinoff company that Beckman had created when NTL's board were dubious about electronics, was reincorporated into Beckman Instruments and became the Helipot Division in 1958. Helipot researchers were experimenting withcermet

A cermet is a composite material composed of ceramic and metal materials.

A cermet can combine attractive properties of both a ceramic, such as high temperature resistance and hardness, and those of a metal, such as the ability to undergo pla ...

s, composite materials made by mixing ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant, and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcela ...

s and metals

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. These properties are all associated with having electrons available at the Fermi level, as against no ...

. Potentiometers made with cermet instead of metal were more heat-resistant, suitable for use at extreme temperatures.

Centrifuges

In 1954, Beckman Instruments acquiredultracentrifuge

An ultracentrifuge is a centrifuge optimized for spinning a rotor at very high speeds, capable of generating acceleration as high as (approx. ). There are two kinds of ultracentrifuges, the preparative and the analytical ultracentrifuge. Both cla ...

maker Spinco (Specialized Instruments Corp.), founded by Edward Greydon Pickels in 1946. This acquisition was the basis of Beckman's Spinco centrifuge

A centrifuge is a device that uses centrifugal force to subject a specimen to a specified constant force - for example, to separate various components of a fluid. This is achieved by spinning the fluid at high speed within a container, thereby ...

division. The division went on to design and manufacture a range of preparative and analytical ultracentrifuges.

Semiconductors

In 1955, Beckman was contacted byWilliam Shockley

William Bradford Shockley ( ; February 13, 1910 – August 12, 1989) was an American solid-state physicist, electrical engineer, and inventor. He was the manager of a research group at Bell Labs that included John Bardeen and Walter Houser Brat ...

. Shockley, who had been one of Beckman's students at Caltech, led Bell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, commonly referred to as ''Bell Labs'', is an American industrial research and development company owned by Finnish technology company Nokia. With headquarters located in Murray Hill, New Jersey, Murray Hill, New Jersey, the compa ...

research program into semiconductor technology

A semiconductor is a material with electrical conductivity between that of a Electrical conductor, conductor and an Insulator (electricity), insulator. Its conductivity can be modified by adding impurities ("doping (semiconductor), doping") to ...

. Semiconductors were, in some ways, similar to cermets. Shockley wanted to create a new company, and asked Beckman to serve on the board. After considerable discussion, Beckman became more closely involved: he and Shockley signed a letter of intent to create the Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory

Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory, later known as Shockley Transistor Corporation, was a pioneering semiconductor developer founded by William Shockley, and funded by Beckman Instruments, Inc., in 1955. It was the first high technology compan ...

as a subsidiary of Beckman Instruments, under William Shockley's direction. The new group would specialize in semiconductors, beginning with the automated production of diffused-base transistors.

Because Shockley's aging mother lived in Palo Alto

Palo Alto ( ; Spanish language, Spanish for ) is a charter city in northwestern Santa Clara County, California, United States, in the San Francisco Bay Area, named after a Sequoia sempervirens, coastal redwood tree known as El Palo Alto.

Th ...

, Shockley wanted to establish the laboratory in nearby Mountain View, California

Mountain View is a city in Santa Clara County, California, United States, part of the San Francisco Bay Area. Named for its views of the Santa Cruz Mountains, the population was 82,376 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census.

Mountain V ...

. Frederick Terman

Frederick Emmons Terman (; June 7, 1900 – December 19, 1982) was an American professor and academic administrator. He was the dean of the school of engineering from 1944 to 1958 and provost from 1955 to 1965 at Stanford University. He is widely ...

, provost at Stanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth ...

, offered the firm space in Stanford's new industrial park. The firm launched in February 1956, the same year that Shockley received the Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

along with John Bardeen

John Bardeen (; May 23, 1908 – January 30, 1991) was an American solid-state physicist. He is the only person to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics twice: first in 1956 with William Shockley and Walter Houser Brattain for their inventio ...

and Walter Houser Brattain

Walter Houser Brattain (; February 10, 1902 – October 13, 1987) was an American solid-state physicist who shared the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics with John Bardeen and William Shockley for their invention of the point-contact transistor. Bra ...

"for their researches on semiconductors and their discovery of the transistor effect". Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory was the first establishment working on silicon semiconductor devices in what came to be known as Silicon Valley.

Shockley, however, lacked experience in business and industrial management. Moreover, he decided that the lab would research an invention of his own, the four-layer diode, rather than developing the diffused silicon transistor that he and Beckman had agreed upon. Beckman was reassured by his engineers that the scientific ideas behind Shockley's project were still sound. When appealed to by members of Shockley's lab, Beckman chose not to interfere with its management. In 1957, eight leading scientists including Gordon Moore

Gordon Earle Moore (January 3, 1929 – March 24, 2023) was an American businessman, engineer, and the co-founder and emeritus chairman of Intel Corporation. He proposed Moore's law which makes the observation that the number of transistors i ...

and Robert Noyce

Robert Norton Noyce (December 12, 1927 – June 3, 1990), nicknamed "the Mayor of Silicon Valley", was an American physicist and entrepreneur who co-founded Fairchild Semiconductor in 1957 and Intel Corporation in 1968. He was also credited w ...

left Shockley's group to form a competing startup, Fairchild Semiconductor

Fairchild Semiconductor International, Inc. was an American semiconductor company based in San Jose, California. It was founded in 1957 as a division of Fairchild Camera and Instrument by the " traitorous eight" who defected from Shockley Semi ...

, which would successfully develop silicon transistors. In 1960, Beckman sold the Shockley subsidiary to the Clevite Transistor Company, ending his formal association with semiconductors. Nonetheless, Beckman had been an essential backer of the new industry in its initial stages.

Computers and automation

Beckman also saw that computers and automation offered a myriad of opportunities for integration into instruments, and the development of new instruments. Beckman Instruments purchased Berkeley Scientific Company in the 1950s, and later developed a Systems Division within

Beckman also saw that computers and automation offered a myriad of opportunities for integration into instruments, and the development of new instruments. Beckman Instruments purchased Berkeley Scientific Company in the 1950s, and later developed a Systems Division within Beckman Instruments

Beckman Coulter, Inc. is a Danaher Corporation company that develops, manufactures, and markets products relevant to biomedical testing. It operates in the industries of diagnostics under the brand name Beckman Coulter and life sciences under t ...

"to develop and build industrial data systems for automation". Berkeley developed the EASE analog computer

An analog computer or analogue computer is a type of computation machine (computer) that uses physical phenomena such as Electrical network, electrical, Mechanics, mechanical, or Hydraulics, hydraulic quantities behaving according to the math ...

, and by 1959 Beckman had contracts with major companies in the aerospace, space, and defense industries, including Boeing Aerospace, Lockheed Aircraft Lockheed (originally spelled Loughead) may refer to:

Brands and enterprises

* Lockheed Corporation, a former American aircraft manufacturer

* Lockheed Martin, formed in 1995 by the merger of Lockheed Corporation and Martin Marietta

** Lockheed Mar ...

, North American Aviation

North American Aviation (NAA) was a major American aerospace manufacturer that designed and built several notable aircraft and spacecraft. Its products included the T-6 Texan trainer, the P-51 Mustang fighter, the B-25 Mitchell bomber, the F- ...

, and Lear Siegler

Lear Siegler Incorporated (LSI) is a diverse American corporation established in 1962. Its products range from car seats and brakes to weapons control systems for military fighter planes. The company's more than $2 billion-a-year annual sales come ...

.

The Beckman Systems Division also developed specialized computer systems to handle large volumes of telemetric radio data from satellites and uncrewed spacecraft. These included systems to process photographs of the Moon, taken by NASA's Ranger spacecraft.

Philanthropy

The Beckmans became increasingly active as philanthropists, with the stated intention of giving away their personal wealth before their deaths. Their first major philanthropic gift went to Caltech. In supporting Caltech, they expanded on the long-term relationship that Beckman had begun as a student at Caltech, and continued as a teacher and trustee. In 1962, they funded the construction of a concert hall, the Beckman Auditorium, designed by architectEdward Durrell Stone

Edward Durell Stone (March 9, 1902 – August 6, 1978) was an American architect known for the formal, highly decorative buildings he designed in the 1950s and 1960s. His works include the Museum of Modern Art, in New York City; the Parliament ...

. Over a period of years, they also supported the Beckman Institute, Beckman Auditorium, Beckman Laboratory of Behavioral Sciences, and Beckman Laboratory of Chemical Synthesis at the California Institute of Technology. In the words of Caltech's president emeritus David Baltimore

David Baltimore (born March 7, 1938) is an American biologist, university administrator, and 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine. He is a professor of biology at the California Institute of Tech ...

, Beckman "has shaped the destiny of Caltech." The Beckmans are also named in the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology

The Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology is a unit of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign dedicated to interdisciplinary research. A gift from scientist, businessman, and philanthropist Arnold O. Beckman (1900–2004) and ...

and the Beckman Quadrangle at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

The Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation was incorporated in September 1977. At the time of Beckman's death, the Foundation had given more than 400 million dollars to a variety of charities and organizations. In 1990, it was considered one of the top ten foundations in California, based on annual gifts. Donations chiefly went to scientists and scientific causes as well as Beckman's ''alma mater

Alma mater (; : almae matres) is an allegorical Latin phrase meaning "nourishing mother". It personifies a school that a person has attended or graduated from. The term is related to ''alumnus'', literally meaning 'nursling', which describes a sc ...

s''. He is quoted as saying, "I accumulated my wealth by selling instruments to scientists ... so I thought it would be appropriate to make contributions to science, and that's been my number one guideline for charity."

In the 1980s, they funded five major centers:

* Beckman Research Institute (BRI) at the City of Hope National Medical Center

City of Hope is a private, non-profit clinical research center, hospital and graduate school located in Duarte, California, United States. The center's main campus resides on of land adjacent to the boundaries of Duarte and Irwindale, California ...

in Duarte, California

Duarte () is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the city population was 21,727. It is bounded to the north by the San Gabriel Mountains, to the north and west by the cities ...

, United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

.

* Beckman Laser Institute, University of California, Irvine

The University of California, Irvine (UCI or UC Irvine) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Irvine, California, United States. One of the ten campuses of the University of California system, U ...

, in Irvine, California

Irvine () is a Planned community, planned city in central Orange County, California, United States, in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. It was named in 1888 for the landowner James Irvine. The Irvine Company started developing the area in the ...

* Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology

The Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology is a unit of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign dedicated to interdisciplinary research. A gift from scientist, businessman, and philanthropist Arnold O. Beckman (1900–2004) and ...

at the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign

* Beckman Center for Molecular and Genetic Medicine at Stanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth ...

, Stanford, California

Stanford is a census-designated place (CDP) in the northwest corner of Santa Clara County, California, United States. It is the home of Stanford University, after which it was named. The CDP's population was 21,150 at the United States Census, ...

* Beckman Institute, California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech) is a private research university in Pasadena, California, United States. The university is responsible for many modern scientific advancements and is among a small group of institutes ...

, Pasadena, California

Pasadena ( ) is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States, northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is the most populous city and the primary cultural center of the San Gabriel Valley. Old Pasadena is the city's original commerci ...

The Beckmans also gave to:

* The Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center for the History of Chemistry at the Chemical Heritage Foundation (now the Science History Institute

The Science History Institute is an institution that preserves and promotes understanding of the history of science. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, it includes a library, museum, archive, research center and conference center.

It was ...

), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

* The Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center of the National Academies of Science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

and Engineering

Engineering is the practice of using natural science, mathematics, and the engineering design process to Problem solving#Engineering, solve problems within technology, increase efficiency and productivity, and improve Systems engineering, s ...

, in Irvine, CA (1988)

* The Pepperdine University School of Business & Management's MBA program (1988)

After Mabel's death in 1989, Arnold Beckman reorganized the foundation to continue in perpetuity, and developed new initiatives for the foundation's giving.

A major focus became the improvement of science education. Beginning in 1998 the Foundation has provided over $23 million to support K-6 hands-on, research-based science education to school districts in Orange County, California, stimulating schools to integrate science into the K-6 curriculum as a core subject.

Arnold Beckman envisioned the Beckman Scholars and Beckman Young Investigators programs to support young scientists at the university level. Each year, the Beckman Foundation selects a list of universities and colleges, each of which selects student from its institution for the Beckman Scholars Program. The Beckman Young Investigators Program provides research support to promising faculty members in the early stages of academic careers in the chemical and life sciences, particularly those whose work involves methods, instruments and materials that may open up new avenues of research in science. In 2017, the Beckman Postdoctoral Fellows award was launched, similarly aimed at supporting promising young postdoctoral scholars in their chemistry or chemical instrumentation research.

The Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation also supports vision research through its Beckman Initiative in Macular Research and the Beckman-Argyros Award in Vision Research. Supported activities include research into laser surgery and macular degeneration.

Awards and honors

In 1971, Beckman was awarded an honorary Doctor of Science (Sc.D.) degree fromWhittier College

Whittier College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Whittier, California. It is a Hispanic-serving institution, Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) and, as of spring 2024, had 815 ...

.

Arnold Beckman was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

in 1976. In 1982, he received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a nonprofit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest-achieving people in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet one ano ...

. Asteroid 3737 Beckman was named after Arnold O. Beckman in 1983. Beckman was inducted into the Junior Achievement US Business Hall of Fame in 1985. In 1987, he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame

The National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF) is an American not-for-profit organization, founded in 1973, which recognizes individual engineers and inventors who hold a US patent of significant technology. Besides the Hall of Fame, it also operate ...

in Akron, Ohio

Akron () is a city in Summit County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Ohio, fifth-most populous city in Ohio, with a population of 190,469 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The Akron metr ...

. In 2004 he received its Lifetime Achievement Award.

Beckman was awarded the National Medal of Technology

The National Medal of Technology and Innovation (formerly the National Medal of Technology) is an honor granted by the president of the United States to American inventors and innovators who have made significant contributions to the development ...

in 1988. It is the highest honor the United States can confer to a US citizen for achievements related to technological progress President George H. W. Bush presented Beckman with the National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral science, behavior ...

Award in 1989, "for his leadership in the development of analytical instrumentation and for his deep and abiding concern for the vitality of the nation's scientific enterprise.". He had previously been recognized by the Reagan administration as one of about 30 citizens receiving the 1989 Presidential Citizens Medal

The Presidential Citizens Medal is an award bestowed by the president of the United States. It is the second-highest civilian award in the United States and is second only to the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Established by executive order on N ...

for exemplary deeds of service.

In 1989, Beckman received the Charles Lathrop Parsons Award

The Charles Lathrop Parsons Award is usually a biennial award that recognizes outstanding public service by a member of the American Chemical Society (ACS). Recipients are chosen by the American Chemical Society Board of Directors, from a list of ...

for public service from the American Chemical Society

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a scientific society based in the United States that supports scientific inquiry in the field of chemistry. Founded in 1876 at New York University, the ACS currently has more than 155,000 members at all ...

.

He was awarded the Order of Lincoln, the state of Illinois' highest honor, by The Lincoln Academy of Illinois

The Lincoln Academy of Illinois is a not-for-profit, non-partisan organization dedicated to recognizing contributions made by living Illinoisans. Named for Abraham Lincoln, the Academy administers the Order of Lincoln, the highest award given b ...

in 1991. In 1996, Beckman was inducted into the Alpha Chi Sigma Hall of Fame. He was awarded the Public Welfare Medal

The Public Welfare Medal is awarded by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences "in recognition of distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare." It is the most prestigious honor conferred by the academy. First awar ...

from the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

in 1999. In 2000, he received a Special Millennium Edition of the Othmer Gold Medal

The Othmer Gold Medal recognizes outstanding individuals who contributed to progress in chemistry and science through their activities in areas including innovation, entrepreneurship, research, education, public understanding, legislation, and ph ...

from the Chemical Heritage Foundation

The Science History Institute is an institution that preserves and promotes understanding of the history of science. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, it includes a library, museum, archive, research center and conference center.

It was ...

in recognition of his multifaceted contributions to chemical and scientific heritage.

The Arnold O. Beckman High School

Arnold O. Beckman High School is a public school in Irvine, California, Irvine, California, United States, serving 3,013 students from grades 9 through 12. The $94 million facility was opened on August 30, 2004. The World Languages Building ...

in Irvine, California

Irvine () is a Planned community, planned city in central Orange County, California, United States, in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. It was named in 1888 for the landowner James Irvine. The Irvine Company started developing the area in the ...

which has a focus in science education, was named in honor of Arnold O. Beckman. It was not, however, funded by Beckman. The Beckman Coulter Heritage exhibit, which discusses the work of scientists Arnold Beckman and Wallace Coulter, is located at the Beckman Coulter headquarters in Brea, California

Brea (; ) is a city in northern Orange County, California, United States. The population as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census was 47,325. It is southeast of Los Angeles. Brea is part of the Los Angeles metropolitan area.

The city ...

.

Personal life

Beckman married Mabel on June 10, 1925. In 1933, the Beckmans built a home inAltadena, California

Altadena () is an unincorporated area, and census-designated place in the San Gabriel Valley and the Verdugos regions of Los Angeles County, California. Directly north of Pasadena, California, Pasadena, it is located approximately from Downtow ...

, in the foothills and adjacent to Pasadena where they lived for over 27 years, raising their family. After Mabel found out she was unable to conceive a child, the couple decided to adopt children, adopting a three year old daughter Gloria Patricia in 1936 and the next year an infant son they named Arnold Stone. Mabel fell in love with a house by the sea in Corona del Mar

Corona del Mar (Spanish for "Crown of the Sea") is a seaside neighborhood in the city of Newport Beach, California. It generally consists of all the land on the seaward face of the San Joaquin Hills south of Avocado Avenue to the city limits, a ...

near Newport Beach

Newport Beach is a coastal city of about 85,000 in southern Orange County, California, United States. Located about southeast of downtown Los Angeles, Newport Beach is known for its sandy beaches. The city's harbor once supported maritime indu ...

, California. They bought the house in 1960, renovated it, and lived there together until Mabel's death in 1989. Arnold Beckman died May 18, 2004, at the age of 104, in hospital in La Jolla, Calif. Mabel and Arnold Beckman are buried beneath a simple headstone in West Lawn Cemetery in Cullom, Illinois, the small town where he was born.

See also

Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation

*

Fairchild Semiconductor

Fairchild Semiconductor International, Inc. was an American semiconductor company based in San Jose, California. It was founded in 1957 as a division of Fairchild Camera and Instrument by the " traitorous eight" who defected from Shockley Semi ...

(a more detailed history of Beckman's role in the founding of Silicon Valley)

Notes

External links

Beckman Coulter

company website

Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation

philanthropic foundation website

Arnold O. Beckman Legacy Project

Science History Institute

The Science History Institute is an institution that preserves and promotes understanding of the history of science. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, it includes a library, museum, archive, research center and conference center.

It was ...

, including a trailer for ''The Instrumental Chemist: The Incredible Curiosity of Arnold O. Beckman''

*

*

*

*

*

Chemical Descent Tree for Arnold Orville Beckman

from th

Chemical Genealogy Database

of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Department of Chemistry

Arnold O. Beckman High School

website

Beckman Historical Collection

Science History Institute

The Science History Institute is an institution that preserves and promotes understanding of the history of science. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, it includes a library, museum, archive, research center and conference center.

It was ...

br>Digital Collections(Digitized corporate records of Beckman Coulter, Incorporated, as well as personal papers of American scientist and industrialist Arnold Orville Beckman)

Guide to the Arnold O. Beckman Papers

Caltech Archives, California Institute of Technology

Interview with Arnold O. Beckman

Caltech Oral Histories {{DEFAULTSORT:Beckman, Arnold O. 1900 births 2004 deaths 20th-century American inventors American men centenarians American chairpersons of corporations American investors American manufacturing businesspeople American nonprofit businesspeople Philanthropists from Illinois American physical chemists American technology chief executives American technology company founders Businesspeople from California Businesspeople from Illinois California Institute of Technology alumni California Institute of Technology faculty Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences National Medal of Science laureates National Medal of Technology recipients University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign alumni Presidential Citizens Medal recipients American scientific instrument makers Silicon Valley people People from Corona, California People from La Jolla, San Diego People from Newport Beach, California People from Livingston County, Illinois People from Altadena, California 20th-century American businesspeople 20th-century American philanthropists Delta Upsilon members