Armagh Rail Disaster on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

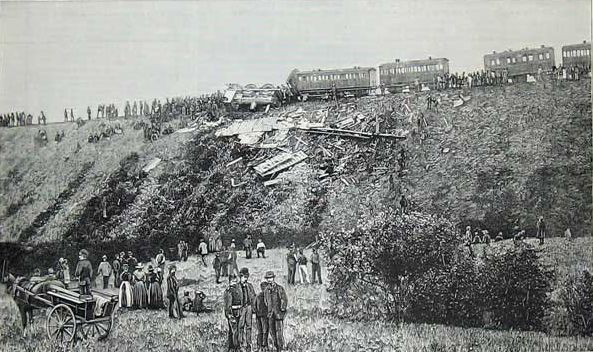

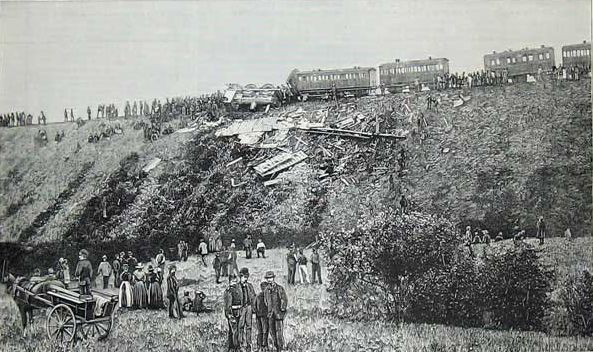

The Armagh rail disaster happened on 12 June 1889 near

The line was operated on the time interval system (rather than block working) so that there was no means at Armagh of knowing that the line was not clear. The required 20-minute interval before letting a fast train follow a slow one having elapsed, the following scheduled passenger train had left Armagh. With an engine of similar performance, but a much lighter train (six vehicles), it was managing about up the gradient when, at a distance of about , the driver of the ordinary train saw the approaching runaway train. He braked his train, and had reduced speed to at the moment of collision.

By now, the runaway train had travelled about . The pursuing driver said he did not believe they had reached more than ; the Board of Trade inspector thought a fair estimate of their speed at the collision. 1½ miles at 1 in 75 is a vertical drop of about and even without any friction or wind resistance, a simple conservation of energy calculation will show that the runaway train coaches could not have reached more than about 56 mph (If this seems too much like original research, note instead that the fall is slightly more than the vertical drop in Box Tunnel; Rolt op cit reports

The line was operated on the time interval system (rather than block working) so that there was no means at Armagh of knowing that the line was not clear. The required 20-minute interval before letting a fast train follow a slow one having elapsed, the following scheduled passenger train had left Armagh. With an engine of similar performance, but a much lighter train (six vehicles), it was managing about up the gradient when, at a distance of about , the driver of the ordinary train saw the approaching runaway train. He braked his train, and had reduced speed to at the moment of collision.

By now, the runaway train had travelled about . The pursuing driver said he did not believe they had reached more than ; the Board of Trade inspector thought a fair estimate of their speed at the collision. 1½ miles at 1 in 75 is a vertical drop of about and even without any friction or wind resistance, a simple conservation of energy calculation will show that the runaway train coaches could not have reached more than about 56 mph (If this seems too much like original research, note instead that the fall is slightly more than the vertical drop in Box Tunnel; Rolt op cit reports

Major General Hutchinson's report into the circumstances of the disaster, with original witness statements

) – Railways Archive Website {{DEFAULTSORT:Armagh Rail Disaster 1889 in Ireland 1880s disasters in Ireland Transport in County Armagh Railway accidents in 1889 Runaway train disasters Armagh (city) History of County Armagh 19th century in County Armagh Accidents and incidents involving Great Northern Railway (Ireland) June 1889 Train collisions in Northern Ireland

Armagh

Armagh ( ; , , " Macha's height") is a city and the county town of County Armagh, in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Primates of All ...

, County Armagh

County Armagh ( ) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It is located in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and adjoins the southern shore of Lough Neagh. It borders t ...

, in Ireland, when a crowded Sunday school

]

A Sunday school, sometimes known as a Sabbath school, is an educational institution, usually Christianity, Christian in character and intended for children or neophytes.

Sunday school classes usually precede a Sunday church service and are u ...

excursion train

An excursion train is a chartered train run for a special event or purpose. Examples are trains to major sporting event, trains run for railfans or tourists, and special trains operated by the railway company for employees and prominent custo ...

had to negotiate a steep incline; the steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, Fuel oil, oil or, rarely, Wood fuel, wood) to heat ...

was unable to complete the climb and the train stalled. The train crew decided to divide the train and take forward the front portion, leaving the rear portion on the running line. The rear portion was inadequately braked and ran back down the gradient, colliding with a following train.

Eighty people were killed and 260 were injured, about a third of them children. It was the worst rail disaster in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

in the nineteenth century, and to this day remains the worst railway disaster in Irish history.The worst railway accident to have occurred in the present-day Republic of Ireland was the Straffan rail accident of 1853, with 18 dead and 2 injured. It is the fourth worst railway accident in the history of the United Kingdom.

At the time, the disaster led directly to various safety measures becoming legal requirements for railways in the United Kingdom. This was important both for the measures introduced and for the move away from voluntarism and towards more direct state intervention in such matters.

Circumstances of the accident

The excursion sets out

Armagh

Armagh ( ; , , " Macha's height") is a city and the county town of County Armagh, in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Primates of All ...

Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

Sunday School had organised a day trip

A day trip is a visit to a tourist destination or visitor attraction from a person's home, hotel, or hostel in the morning, returning to the same lodging in the evening. The day trip is a form of recreational travel and leisure to a location t ...

to the seaside resort of Warrenpoint

Warrenpoint () is a small port town and civil parish in County Down, Northern Ireland. It sits at the head of Carlingford Lough, south of Newry, and is separated from the Republic of Ireland by a narrow strait. The town is beside the village ...

, County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 552,261. It borders County Antrim to the ...

, a distance of about . A special Great Northern Railway of Ireland

The Great Northern Railway (Ireland) (GNR(I), GNRI or simply GNR) was an Irish gauge () railway company in Ireland. It was formed in 1876 by a merger of the Irish North Western Railway (INW), Northern Railway of Ireland, and Ulster Railway. ...

(GNR(I)) train was arranged for the journey, intended to carry about eight hundred passengers.

The railway route was steeply graded and curved, and the first from Armagh railway station involved a steep continuous climb, up a gradient of 1 in 82 (1.22%) and then 1 in 75 (1.33%). Elsewhere on the line, there were gradients as severe as 1 in 70.2 (1.42%).''Report of the Board of Trade (Railway Department) into the circumstances of the collision near Armagh on 12th June 1889'', Maj-Gen C S Hutchinson

Asked to provide rolling stock

The term rolling stock in the rail transport industry refers to railway vehicles, including both powered and unpowered vehicles: for example, locomotives, Railroad car#Freight cars, freight and Passenger railroad car, passenger cars (or coaches) ...

for a special train to take 800 excursionists, the locomotive department at Dundalk

Dundalk ( ; ) is the county town of County Louth, Ireland. The town is situated on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the north-east coast of Ireland, and is halfway between Dublin and Belfast, close to and south of the bor ...

sent fifteen vehicles hauled by a 'four-coupled'the familiar Whyte notation was not yet in use (first used in 1900) (2-4-0

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, represents the wheel arrangement of two leading wheels on one axle, four powered and coupled driving wheels on two axles and no trailing wheels. In most of North America it b ...

) locomotive;http://www.steamindex.com/locotype/gnri.htm gives a ''catalogue raisonée'' of the various engines of the GNR(I). From the details given in the accident report, the excursion train engine appears to have been one of the GNR(I)'s H class however, the instructions to the engine driver

A train driver is a person who operates a train, railcar, or other rail transport vehicle. The driver is in charge of and is responsible for the mechanical operation of the train, train speed, and all of the train handling (also known as bra ...

, Thomas McGrath, were that the train was to be of thirteen vehicles. There were more intending passengers than anticipated and, to accommodate the excursion, the Armagh station master

The station master (or stationmaster) is the person in charge of a Train station, railway station, particularly in the United Kingdom and many other countries outside North America. In the United Kingdom, where the term originated, it is now lar ...

decided to use all fifteen vehicles. McGrath, who had never driven the route before (but had been over it with excursion trains when a fireman

A firefighter (or fire fighter or fireman) is a first responder trained in specific emergency response such as firefighting, primarily to control and extinguish fires and respond to emergencies such as hazardous material incidents, medical in ...

), objected to these instructions, saying that his instructions were that the train was to be of thirteen vehicles at most. According to the driver:

Two other witnesses said that McGrath had asked for a second engine if more carriages

A carriage is a two- or four-wheeled horse-drawn vehicle for passengers. In Europe they were a common mode of transport for the wealthy during the Roman Empire, and then again from around 1600 until they were replaced by the motor car around 1 ...

were added and had been refused by the station master, as none was available; McGrath (in supplementary evidence given "through the railway company's officers") denied this. The station master's evidenceAccident report – evidence of John Foster (the station master) was that the discussion was about adding further carriages to the fifteen with which the locomotive had arrived.It is not clear that all witnesses agreed as to whether brake-vans counted as carriages or vehicles, the string with which the locomotive arrived is variously described as fifteen vehicles, fifteen carriages, and thirteen vehicles and two brake vans The general manager's chief clerk was to accompany the excursion; he suggested that the engine of the routine train that would be following twenty minutes behind could assist the excursion up the bank, or that some carriages could be left to come on with the routine train. Following his conversation with the station master, however, McGrath refused the assistance.

The train therefore set off with fifteen carriages, containing about 940 passengers.The 1881 Census for Ireland reports the population of the parliamentary borough of Armagh to have been under 9,000. The organisers of the excursion subsequently were sent a bill for £39 4s 3d for 941 excursion tickets to Warrenpoint (''Birmingham Daily Post

The ''Birmingham Post'' is a weekly printed newspaper based in Birmingham, England, with distribution throughout the West Midlands. First published under the name the ''Birmingham Daily Post'' in 1857, it has had a succession of distinguished ...

'', Monday 1 July 1889), for which the railway company later apologised The carriages were full, and some passengers travelled with the guards. Tickets were checked before setting off and to prevent people without tickets joining the excursion; once each compartment had been checked its doors were locked.This was described as standard practice for excursions, however it was contrary to Board of Trade recommendations made after a railway fire at Versailles in 1842 (that one door to a compartment should not be locked) and after the Abergele rail disaster

The Abergele rail disaster took place near Abergele, North Wales, in August 1868. At the time, it was the worst railway disaster to have occurred in Great Britain.

The Irish Mail train was on its way from London to Holyhead. At Llanddulas -- t ...

in 1868 (that all doors should be unlocked).

Initially the train made progress up the steep gradient at about but stalled about before the top of the gradient.Accident report – evidence of Thomas McGrath

Dividing the excursion train

To prevent the train rolling back, the brakes were applied. The train did have continuousbrakes

A brake is a mechanical device that inhibits motion by absorbing energy from a moving system. It is used for slowing or stopping a moving vehicle, wheel, axle, or to prevent its motion, most often accomplished by means of friction.

Background

...

, (''i.e.'', all carriages had brakes which could be operated by the driver), but they were of the non-automatic vacuum type. They were applied by creation of vacuum in the brake pipes and released by admitting air to the pipe.

This was the opposite of the arrangement preferred by the Board of Trade ('automatic continuous brakes') in which brakes were held off by vacuum (or compressed air) generated by the engine, so that on loss of vacuum (e.g. from a leaky connection or a connection parting) the brakes came on automatically. The two brake van

Brake van and guard's van are terms used mainly in the UK, Ireland, Australia and India for a Rolling stock, railway vehicle equipped with a hand brake which can be applied by the Conductor (transportation), guard. The equivalent North Americ ...

s, however, (one immediately behind the engine tender, the other at the rear of the train) also had hand-operated brakes, each under the control of a guard. These were applied.according to the guards

The chief clerk directed the train crew to divide the train and proceed with the front portion to Hamilton's Bawn

Hamiltonsbawn or Hamilton's Bawn is a village in County Armagh, Northern Ireland, five miles (8 km) east of Armagh. It lies within the civil parish of Mullabrack and the Armagh, Banbridge and Craigavon District Council area. It had a popu ...

station, about away, and leave that portion there, and return for the second portion. Owing to limited siding capacity at Hamilton's Bawn, only the front five vehicles could be taken on there; so the rearmost ten vehicles would have to be left standing on the running line. Once this rear portion was uncoupled from the front portion, the continuous brakes on it would be released, and the only brakes holding it against the gradient would be the hand-operated brakes in the rear brake van.

For a goods (freight) train in a similar situation, the wheels would have been 'scotched'wedged or chocked, see wikt:scotch#Verb 4 against roll-back, and guard's vans on goods trains carried 'sprags'pieces of wood to place in between wheel spokes in order to prevent rotation, see wikt:sprag#Verb 1 with which to do this. Those on passenger trains with continuous brakes were not required to carry sprags, and the excursion train did not. The guard in the rear van having applied his handbrake then (on the instructions of the chief clerk) dismounted and scotched the wheels of his van with pieces of ballast. He then also scotched the near rearmost vehicle on its righthand wheels and intended to similarly scotch its lefthand wheels before going back down the track with flags and detonators

A detonator is a device used to make an explosive or explosive device explode. Detonators come in a variety of types, depending on how they are initiated (chemically, mechanically, or electrically) and details of their inner working, which of ...

to protect the train from the scheduled service which was to set off from Armagh 20 minutes after the excursion.

The train was screw-coupled; each carriage was first coupled by a loose chain and hook coupling to the next; the slack on this was then taken up by a turnbuckle screw arrangement, until the buffers of the two carriages were touching. To uncouple, there needed to be some slack in the coupling; as the train had stopped all the couplings were under tension. Once the vacuum brake connection to the rear portion was broken, any attempt to introduce slack into the coupling between the two portions would be defeated by the rear portion settling back to rest its weight upon the rear van brakes. To assist uncoupling the front van guard therefore scotched one of the wheels of the sixth vehicle, that is, the front vehicle of the rear portion being detached. Loosening the turnbuckle thus transferred the weight of the rear portion to the scotch on the sixth vehicle, rather than to the rear van brakes. The couplings to the rear of the sixth vehicle remained under tension, and the slack introduced remained in the coupling between the fifth and sixth vehicles, which could be unhooked.

The rear carriages run away

The uncoupling accomplished by the front van guard, the driver attempted to start the front portion away. It rolled back slightly, in the opinion of the front guard – Accident return – evidence of William Moorehead jolting the rear portion; which caused the wheels of the front vehicle of the rear portion to ride up over the stones underneath them. The rear portion had been standing with its couplings tight, but now only the rear two vehicles were in any way restrained, so that the leading eight vehicles of the rear portion fell back on to them. The momentum of the eight vehicles closing on the rear two was sufficient to push them over the stones, crushing them in turn, so that now only the handbrake on the rear brake van was effective. It was overcome by the weight of ten vehicles, and the rear portion began to move downhill and gathered speed down the steep gradient back towards Armagh Station. The train crew reversed the front portion and tried to catch the rear portion and re-couple it, but this proved to be impossible.Collision

The line was operated on the time interval system (rather than block working) so that there was no means at Armagh of knowing that the line was not clear. The required 20-minute interval before letting a fast train follow a slow one having elapsed, the following scheduled passenger train had left Armagh. With an engine of similar performance, but a much lighter train (six vehicles), it was managing about up the gradient when, at a distance of about , the driver of the ordinary train saw the approaching runaway train. He braked his train, and had reduced speed to at the moment of collision.

By now, the runaway train had travelled about . The pursuing driver said he did not believe they had reached more than ; the Board of Trade inspector thought a fair estimate of their speed at the collision. 1½ miles at 1 in 75 is a vertical drop of about and even without any friction or wind resistance, a simple conservation of energy calculation will show that the runaway train coaches could not have reached more than about 56 mph (If this seems too much like original research, note instead that the fall is slightly more than the vertical drop in Box Tunnel; Rolt op cit reports

The line was operated on the time interval system (rather than block working) so that there was no means at Armagh of knowing that the line was not clear. The required 20-minute interval before letting a fast train follow a slow one having elapsed, the following scheduled passenger train had left Armagh. With an engine of similar performance, but a much lighter train (six vehicles), it was managing about up the gradient when, at a distance of about , the driver of the ordinary train saw the approaching runaway train. He braked his train, and had reduced speed to at the moment of collision.

By now, the runaway train had travelled about . The pursuing driver said he did not believe they had reached more than ; the Board of Trade inspector thought a fair estimate of their speed at the collision. 1½ miles at 1 in 75 is a vertical drop of about and even without any friction or wind resistance, a simple conservation of energy calculation will show that the runaway train coaches could not have reached more than about 56 mph (If this seems too much like original research, note instead that the fall is slightly more than the vertical drop in Box Tunnel; Rolt op cit reports Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( ; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history", "one of the 19th-century engi ...

to have rebutted Dionysius Lardner

Dionysius Lardner FRS FRSE (3 April 179329 April 1859) was an Irish scientific writer who popularised science and technology, and edited the 133-volume '' Cabinet Cyclopædia''.

Early life in Dublin

He was born in Dublin on 3 April 1793 th ...

's prediction of for a train going down the tunnel without brakes by showing the correct answer to be )

The engine of the scheduled train overturned, and the connection to its tender was lost. This train was also fitted with 'simple' (non-automatic) continuous vacuum brakes, and these were lost when the engine became disconnected. The train split into two sections, both running back down the gradient towards Armagh. Application of the handbrakes on the tender and on the brake van brought the front and rear halves of the scheduled train to a stop without further incident, a witness telling the inspector "The tender was slightly damaged, but none of the vehicles, and I heard from the guard that a horse in the box next the tender was not injured".

The occupants of the rear of the excursion train were not so lucky. The two rearmost vehicles of the excursion train were utterly destroyed, and the third rearmost very badly damaged. The debris tumbled down a embankment.

Causes of the runaway

Inadequate application of brakes

As part of his investigations, the Board of Trade inspector carried out calculations which established that a train similar to the excursion train could be hauled over the Armagh bank at about by the excursion train engine, and supported this by a practical trial. However, he did criticise the allocation of an engine with only just enough power for such a duty, especially with a driver who had little knowledge of the route. A further practical trial showed that a single brake van, with the brake correctly working and correctly applied, could (without the aid of scotching) hold 10 carriages on the Armagh bank, against both their own weight and a nudge similar to that which witnesses agreed in describing as having been caused by run-back of the front portion of the divided train. Hence, the problem was not the inadequacy of the brake.The immediate cause was the want of the application of sufficient brake power to hold the rear portion of the excursion train, when this portion, consisting of nine coaches and a brake van; which had been separated from the front of the train by direction of Mr. Elliott, was slightly bumped by the front portion of the train when the driver had to set back previously to starting for Hamilton's Bawn.Two witnesses had seen the brake working properly before the train left Armagh, and the brake apparatus had been found in the wreckage and appeared to be in good working order. Nonetheless, the rear portion had run away, and had done so with the braked wheels revolving freely. Therefore, either the brake had not been applied properly by the guard, or it had been tampered with by passengers in the brake carriage. In the circumstances, the guard should be given the benefit of the doubt.

Incorrect response to the excursion train stalling

Responsibility lay primarily with Mr Elliott, the chief clerk. He had directed a course of action which ignored Company rules. These laid down that the main guard should not leave his van until perfectly satisfied that his brake would hold the train (the train should therefore have been allowed to ease back upon the rear brake van); once he had left his brake, no attempt should be made to move the train until he was back at the brake. Meanwhile, the more junior guard should have gone back down the track to protect the train. These precautions had been omitted, to pursue a strategy (dividing the train) which, even had nothing gone wrong, would have had no advantages over awaiting the scheduled train to assist the excursion to Hamilton's Bawn.If Mr. Elliott had therefore only had the prudence to wait where the excursion train stopped near the top of the bank and to send back one of the guards to protect his train, with instructions to ask the driver of the following ordinary train to help the excursion train up the short remaining distance, he would hardly have lost time and would, besides, have avoided the risk inseparable from the delicate operation he unwisely determined to carry out and which should have been resorted to under only most exceptional circumstances and not, as in the present case, where there was so easy a solution of the difficulty.

Other criticisms

Wrong driver, wrong engine

The excursion train (even in the 15-vehicle form in which it set off) should have been able to climb Armagh bank at about . The inspector considered that its failure to do so must have been "due to some want of proper management of the engine" by its insufficiently experienced driver. The locomotive shed foreman atDundalk

Dundalk ( ; ) is the county town of County Louth, Ireland. The town is situated on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the north-east coast of Ireland, and is halfway between Dublin and Belfast, close to and south of the bor ...

was criticised for want of judgment in not sending a more experienced driverHe suggested in his evidence that there had been no problem with the engine but the brakes had been tampered with. No reason was given in the accident return for discounting the possibility that the train had been held back by wrongly applied brakes. ''The Oxford Companion to British Railway History'' notes – in its article on brakes (p 39) – of the simple vacuum system.

It might also be noted that, when the various continuous braking systems had been trialled at Newark in 1875 on one run, the train with vacuum brakes "failed to attain sufficient speed due to imperfect release of the brake blocks". and in his choice of engine. The 2-4-0 supplied would have had insufficient margins (even when hauling a 13-vehicle excursion train) to be sure of maintaining a safe speedThe line was run on the time interval system and it was therefore dangerous to go much slower than the train behind over the more onerous gradients farther up the line. For a 15-vehicle excursion, assistance should have been given by the engine of the regular train.

Failure to provide an assisting engine

The report criticised the "over-confidence" of the excursion engine driver as to the capabilities of his engine and regretted that his better judgment must have been overcome by the words of the Armagh station master. The chief clerk came in for further criticism for not having persisted with his instructions for the regular train engine to provide assistance. There was no direct criticism of the station master; either for having increased the size of the train, or for persuading the engine driver to attempt Armagh bank without assistance.The excursion train

The organisation of this was criticised on a number of points: *Passengers should not have been allowed to travel in the brake vans, "a practice that should be sternly prohibited" *Carriage doors should not have been locked: "a wrong thing" *Given the weight of the train and the gradients on the line, both brake vans should have been at the rear of the train *It should not have been so big:Findings of the inquest

The inquest was completed on Friday 21 June 1889, and made findings of culpable negligence against six of those involved; those at Dundalk responsible for selection of the engine, the driver and both guards on the train, and Mr Elliott who had taken charge. As a result, three of the accused were committed for trial for manslaughter on the following Monday. One guard had been injured in the crash and was presumably still in hospital; the Dundalk personnel were not charged, the 'practical trial' showing that the engine supplied should not have been defeated by Armagh bank if correctly handled having been carried out on Saturday 22 June. The jury are not reported to have made any findings against more senior management of the Great Northern Railway of Ireland. Elliott was tried in Dublin in August, when the jury reported they were unable to agree; on re-trial in October he was acquitted. The cases against the other defendants were then dropped.Recommendation and consequent legislation

Recommendation triggering legislation

The key recommendation was in fact couched as a finding:Regulatory background

For many years the Railway Inspectorate of theBoard of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for Business and Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

had been advocating three vital safety measures (among others) to often reluctant railway managements:

;lock: interlocking

In railway signalling, an interlocking is an arrangement of signal apparatus that prevents conflicting movements through an arrangement of tracks such as junctions or crossings. In North America, a set of signalling appliances and tracks inte ...

of points and signals, so that conflicting signal indications are prevented

;block: A space-interval or absolute block

Absolute block signalling is a British signalling block system designed to ensure the safe operation of a railway by allowing only one train to occupy a defined section of track (block) at a time. Each block section is manually controlled by ...

system of signalling

A signal is both the process and the result of transmission of data over some media accomplished by embedding some variation. Signals are important in multiple subject fields including signal processing, information theory and biology.

In ...

, where one train is not allowed to enter a physical section until the preceding one had left it

;brake: Continuous brakes

A brake is a mechanical device that inhibits motion by absorbing energy from a moving system. It is used for slowing or stopping a moving vehicle, wheel, axle, or to prevent its motion, most often accomplished by means of friction.

Background

...

, to put at the command of the engine driver adequate braking power; this requirement being increased as the technology made it reasonable to 'automatic' (in modern parlance 'fail-safe') continuous brakes which had to be 'held off' by vacuum or compressed air and would be applied automatically if that supply was lost (e.g. if a train were divided).

The Board of Trade had got as far and as fast as it could by persuasion, but an inspector commented in 1880 after the Wennington Junction rail crash:

Questions in Parliament

In the aftermath of the accident, questions to the President of the Board of Trade Sir Michael Hicks Beach revealed that * in the whole of Ireland only one engine and six vehicles were equipped with an automatic continuous brake * in England 18% of the passenger rolling stock had no continuous brake, and a further 22% had non-automatic brakes * in Scotland 40% of the passenger rolling stock were without continuous brakes More specifically, for the Great Northern of Ireland: *in March 1888 there were 208 drivers and firemen employed and 693 occasions on which they worked a 14-hour day or longer, including two in which they worked over 18 hoursThe questioner ( the MP for West Belfast) also alleged which somewhat overstated the case; they had served as guards from time to time in the past. * of the 518 miles of railway it worked, only 23 were worked on the block system T W Russell, House of Commons Debates 15 July 1889 vol338 c392 * It had no engines or vehicles whose brakes met the requirements of the Board of Trade, furthermore:New legislation

The government was already short of parliamentary time in which to pass legislation it was already committed to, and had promised to introduce no further controversial measures. A bill was drafted and introduced, only to be withdrawn when it became clear that some of its other provisions (most notably requiring specified improvements in couplings, so that those engaged in shunting could safely uncouple wagons without having to step into the gap between them) were sufficiently contentious as to jeopardise passage of the non-controversial portions of the bill. For that reason, some Liberal MPs sympathetic to railwaymen's concerns on working hours and the hazards of shuntingamongst them noticeably the MP for Crewe expressed disappointment that the bill did not go far enough. On the other hand, during the second reading Sir John Brunner, 1st Baronet, a Liberal MP made the classic argument against detailed and prescriptive regulation: Nonetheless, within two months of the Armagh disasterParliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

had enacted the Regulation of Railways Act 1889

The Regulation of Railways Act 1889 ( 52 & 53 Vict. c. 57) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is one of the Railway Regulation Acts 1840 to 1893. It was enacted following the Armagh rail disaster.

Safety

It empowered the B ...

, which authorised the Board of Trade to require the use of continuous automatic brakes on passenger railways, along with the block system of signalling and the interlocking of all points and signals. This is often taken as the beginning of the modern era in UK rail safety.

Similar accidents

*Round Oak rail accident

The Round Oak railway accident happened on 23 August 1858 between Brettell Lane railway station, Brettell Lane and Round Oak railway station, Round Oak railway stations, on the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway. The breakage of a defe ...

– 1 in 75; 23 August 1858 – Excursion runaway; brake not applied

* Abergele rail disaster

The Abergele rail disaster took place near Abergele, North Wales, in August 1868. At the time, it was the worst railway disaster to have occurred in Great Britain.

The Irish Mail train was on its way from London to Holyhead. At Llanddulas -- t ...

– 26 August 1868 – Brake broken by rough shunting

* Stairfoot rail accident – 12 September 1870 – Poorly secured wagons runaway due to rough shunting

* Murulla railway accident (26 killed) – 13 September 1926 – Air brake failure

* Bouhalouane train crash (131 killed) – 27 January 1982 – Passenger carriage roll back after being disconnected from a locomotive on a steep slope.

* 13 die near Kisumu

Kisumu ( ) is the third-largest city in Kenya located in the Lake Victoria area in the former Nyanza Province. It is the second-largest city after Kampala in the Lake Victoria Basin. The city has a population of slightly over 600,000. The ...

, Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

, after a passenger train rolls back because of air brake failure – 15 August 2000

* Tenga rail disaster – 25 May 2002

* Igandu train disaster

The Igandu train disaster occurred during the early morning of June 24, 2002, in Tanzania. It is one of the worst rail accidents in African history. A passenger train with over 1,200 people on board rolled backwards down a hill into a slow movi ...

– 24 June 2002

See also

*History of rail transport in Ireland

The history of rail transport in Ireland began only a decade later than that of History of rail transport in Great Britain, Great Britain. By its peak in 1920, Ireland had 3,500 route miles (5,630 km). The current status is less than half ...

* Lists of rail accidents

A rail accident (or train wreck) is a type of disaster involving one or more trains. Train wrecks often occur as a result of miscommunication, as when a moving train meets another train on the same track, when the wheels of train come off the ...

* List of steepest gradients on adhesion railways

This is a list of steep grades along adhesion railways, the most common type of railway that relies on the friction between the drive wheels and the tracks for traction. The inclusion of steep gradients on railways avoids the expensive engineeri ...

Notes and references

Notes ReferencesFurther reading

*External links

Major General Hutchinson's report into the circumstances of the disaster, with original witness statements

) – Railways Archive Website {{DEFAULTSORT:Armagh Rail Disaster 1889 in Ireland 1880s disasters in Ireland Transport in County Armagh Railway accidents in 1889 Runaway train disasters Armagh (city) History of County Armagh 19th century in County Armagh Accidents and incidents involving Great Northern Railway (Ireland) June 1889 Train collisions in Northern Ireland