Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as

Prime Minister of France

The prime minister of France (), officially the prime minister of the French Republic (''Premier ministre de la République française''), is the head of government of the French Republic and the leader of its Council of Ministers.

The prime ...

during the

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliation politics during the

interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

(19181939).

In 1926, he received the

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

along with German Foreign Minister

Gustav Stresemann

Gustav Ernst Stresemann (; 10 May 1878 – 3 October 1929) was a German statesman during the Weimar Republic who served as Chancellor of Germany#First German Republic (Weimar Republic, 1919–1933), chancellor of Germany from August to November 1 ...

for the realization of the

Locarno Treaties

The Locarno Treaties, known collectively as the Locarno Pact, were seven post-World War I agreements negotiated amongst Germany, France, Great Britain, Belgium, Italy, Second Polish Republic, Poland and First Czechoslovak Republic, Czechoslovak ...

, which aimed at reconciliation between France and Germany after the

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

To avoid another worldwide conflict, he was instrumental in the agreement known as the

Kellogg–Briand Pact

The Kellogg–Briand Pact or Pact of Paris – officially the General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy – is a 1928 international agreement on peace in which signatory states promised not to use war t ...

of 1928, as well to establish a "

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

" in 1929. However, all his efforts were compromised by the rise of nationalistic and

revanchist ideas like

Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

and

fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

following the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

.

Early life

He was born in

Nantes

Nantes (, ; ; or ; ) is a city in the Loire-Atlantique department of France on the Loire, from the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. The city is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, sixth largest in France, with a pop ...

,

Loire-Inférieure (now Loire-Atlantique) of a ''

petit bourgeois'' family. He attended the

Nantes Lycée, where, in 1877, he developed a close friendship with

Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet and playwright.

His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the ''Voyages extraor ...

. He studied law at the

Faculty of Law of Paris

The Faculty of Law of Paris (), called from the late 1950s to 1970 the Faculty of Law and Economics of Paris, is the second-oldest faculty of law in the world and one of the four and eventually five faculties of the University of Paris ("the S ...

, and soon went into politics, associating himself with the most advanced movements, writing articles for the

syndicalist

Syndicalism is a labour movement within society that, through industrial unionism, seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes and other forms of direct action, with the eventual goal of gainin ...

journal ''Le Peuple'', and directing the ''Lanterne'' for some time. From this he passed to the ''Petite République'', leaving it to found , in collaboration with

Jean Jaurès.

Activism

At the same time he was prominent in the movement for the formation of trade unions, and at the congress of workers at Nantes in 1894, he secured the adoption of the labor union idea against the adherents of

Jules Guesde

Jules Bazile, known as Jules Guesde (; 11 November 1845 – 28 July 1922) was a French socialist journalist and politician.

Guesde was the inspiration for a famous quotation by Karl Marx. Shortly before Marx died in 1883, he wrote a letter ...

. From that time, Briand was one of the leaders of the

French Socialist Party

The Socialist Party ( , PS) is a Centre-left politics, centre-left to Left-wing politics, left-wing List of political parties in France, political party in France. It holds Social democracy, social democratic and Pro-Europeanism, pro-European v ...

. In 1902, after several unsuccessful attempts, he was elected deputy. He declared himself a strong partisan of the union of the

left in what was known as the ''Bloc'', to check the reactionary deputies of the right.

From the beginning of his career in the

Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

, Briand was occupied with the question of the

separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

. He was appointed the reporter of the commission charged with the preparation of the

1905 law on separation, and his report at once marked him out as one of the coming leaders. He succeeded in carrying his project through with but slight modifications, and without dividing the parties upon whose support he relied.

He was the principal author of the law of separation, but, not content with preparing it; he wished to apply it as well. The ministry of

Maurice Rouvier was allowing disturbances during the taking of inventories of church property, a clause of the law for which Briand was not responsible. Consequently, he accepted the

portfolio of

Public Instruction and Worship in the

Sarrien ministry (1906). So far as the chamber was concerned, his success was complete. But the acceptance of a position in a bourgeois ministry led to his exclusion from the Unified Socialist Party (March 1906). As opposed to Jaurès, he contended that the Socialists should co-operate actively with the Radicals in all matters of reform, and not stand aloof to await the complete fulfillment of their ideals.

He himself was atheist.

He became a

freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

in the

lodge Le Trait d'Union in July 1887 while the lodge did not record his name in spite of his repeated requests.

Le Trait d'Union Orient de Saint-Nazaire lodge had declared him "unworthy of belonging to the great masonic family on 6 September 1889". In 1895 he joined the lodge Les Chevaliers du Travail that was established in 1893.

Prime Minister of France

Pre-war

Briand served as

Minister of Justice under

Clemenceau in 1908–9, before succeeding Clemenceau as

Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

on 24 July 1909, serving until 2 March 1911. In social policy, Briand's first ministry was notable for the passage of a bill in April 1910 for workers' and farmers' pensions. That same year, compulsory sickness and old-age insurance was introduced for 8 million rural and urban workers. However, a law court decision in 1912 that questioned the legality of compulsion "enabled a large proportion of employers and workers to evade the law."

Briand again served as Minister of Justice 1912-13 under the premiership of the rightwinger

Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France. He was a conservative leader, primarily committed to ...

(soon to become

president of the Republic), before again becoming Prime Minister for a few months from 21 January 1913 until 22 March 1913.

First World War

1914–15

At the end of August 1914, following the outbreak of the First World War, Briand again became Minister of Justice when

René Viviani reconstructed his ministry. In the winter of 1914–15 Briand was one of those who pushed for an expedition to

Salonika, in the hope of helping Serbia, and perhaps bringing Greece, Romania, Bulgaria and Italy into the war as a pro-French bloc, which would also act as a barrier to future Russian expansion in the Balkans. He got on well with

Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, who was also, contrary to military advice, keen for operations in the Balkans, and had a long talk with him on 4 February 1915. Briand was the main mover in persuading

Maurice Sarrail to accept the Salonika command in August 1915.

In October 1915 following

an unsuccessful French offensive and

the entry of Bulgaria, Briand again became Prime Minister (29 October 1915), succeeding René Viviani. He also became Foreign Minister for the first time, a post held by

Théophile Delcassé until the final weeks of the previous government. He was also pledged to "''unité de front''", not just between the military and Parliament but also closer links with the other Allies, a pledge met with "prolonged, thunderous applause" by the deputies.

[Greenhalgh 2005, pp. 36, 38–9]

Draft proposals for Allied cooperation, prepared by

Lord Esher and

Maurice Hankey were on the table by the time British Prime Minister

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

visited Paris on 17 November (mainly to discuss Greece, and only his second wartime talks with France; the first had been with Viviani in July 1915).

The opening weeks of Briand's ministry required him to broker an agreement between

General Gallieni, the new War Minister, and

General Joffre, newly (2 December) promoted to "Commander-in-Chief of the French Armies" (''generalissimo'') over ''all'' theatres apart from North Africa.

1916

In the poisonous atmosphere after the opening of the

German attack at Verdun (21 February 1916), Gallieni read an angry report at the Council of Ministers on 7 March criticising Joffre's conduct of operations over the last eighteen months and demanding ministerial control, then resigned. He was falsely suspected of wanting to launch a military takeover of the government. Briand knew that publication of the report would damage morale and might bring down the government. Gallieni was persuaded to remain in office until a replacement had been agreed.

General Roques was appointed after it had been ensured that Joffre had no objections.

The first formal Allied conference met in Paris on 26 March 1916 (Italy did not participate) but initially made little impact, perhaps because Briand had vetoed the British suggestion of a permanent secretariat, or perhaps because there had been three informal sets of Anglo-French talks in the last quarter of 1915, one of which, the Chantilly meeting, had already seen strategy plans drawn up.

Late in March 1916 Joffre and Briand blocked the withdrawal of five British divisions from

Salonika. Briand was widely suspected of wanting to help his mistress

Princess George of Greece, who was born a Bonaparte. In the spring of 1916 Briand urged Sarrail to take the offensive in the Balkans to take some of the heat off Verdun, although the British, preoccupied with the upcoming Somme offensive, declined to send further troops and Sarrail's offensive that summer was not a success. Briand also attended the conference at Saleux on 31 May 1916 about the upcoming Anglo-French offensive on the Somme, with President Poincaré (on whose train it was held),

General Foch (commander, Army Group North) and the British Commander-in-Chief

General Haig.

The first Secret Session of the Chamber of Deputies was held in June 1916 to discuss the shortcomings of the defence at Verdun. The government won a vote of confidence but with a clause demanding "effective supervision" of the army. The Parliamentary Army Commission elected

Abel Ferry as a commissioner (1 August). By October Ferry was presenting his fourth report on army railways, to Joffre's fury.

[Greenhalgh 2014, p. 167-8]

Late in 1916 Roques had been sent on a fact-finding mission to Salonika after Britain, Italy and Russia had pushed for the dismissal of the theatre commander

Sarrail. To Briand's and Joffre's surprise, Roques returned recommending that Sarrail be reinforced and that Sarrail no longer report to Joffre. Coming on the back of the disappointing results of the

Somme campaign and the

defeat of Romania, Roques' report further discredited Briand and Joffre and added to the Parliamentary Deputies' demands for a closed session.

[Doughty 2005, p318-20] In November Ferry presented a report on the shortage of manpower. A secret session was held on 21 November about calling up the Class of 1918 followed by another a week later.

On 27 November Briand proposed that Joffre be effectively demoted to commander-in-chief in northern France, with both he and Sarrail reporting to the War Minister, although he withdrew this proposal after Joffre threatened resignation. The Closed Session began on 28 November and lasted until 7 December. Briand had little choice but to make concessions to preserve his government, and in a speech of 29 November he promised to repeal Joffre's promotion of December 1915 and in vague terms to appoint a general as technical adviser to the government. Briand survived a confidence vote by 344-160 (six months earlier he had won a confidence vote 440-80).

Reconstructed government

On 13 December Briand formed a new government, reducing the size of the Council of Ministers from 23 to 10 and replacing Roques with

General Lyautey. That day his government survived a vote of confidence by 30 votes, and Joffre was appointed "general-in-chief of the French armies, technical adviser to the government, consultative member of the War Committee" (he was persuaded to accept by Briand, but soon found that he had been stripped of real power and asked to be relieved altogether on 26 December), with

Nivelle replacing him as commander-in-chief of the Armies of the North and Northeast.

A Senate Secret Session on 21 December attacked Briand's plans for a smaller war cabinet as "yet another level of bureaucracy"; on 23 December Briand pledged that he would continue to push for a "permanent Allied bureau" to secure constant cooperation between the Allied nations. Briand's reduced War Cabinet was formed in imitation of the small executive body formed by Lloyd George, just appointed Prime Minister of Britain, but in practice Briand's often met just prior to meetings of the main Cabinet.

Painlevé declined the job of War Minister as he would have preferred

Petain as commander-in-chief rather than the inexperienced Nivelle. Like President Poincaré Briand had thought Petain too cautious to be suitable.

Nivelle's appointment caused great friction between the British and French high commands, after Lloyd George attempted to have Haig placed under Nivelle's command at the

Calais Conference in January. Briand only reluctantly agreed to attend another allied conference in London (12–13 March 1917) to resolve the matter. Briand resigned as Prime Minister on 20 March 1917 as a result of disagreements over the prospective

Nivelle Offensive, to be succeeded by

Alexandre Ribot.

1920s

Briand returned to power in 1921. He supervised the French role in the

Washington Naval Conference of 1921–22. Three factors guided the French strategy and necessitated a Mediterranean focus: the French navy needed to carry a great many goods, the Mediterranean was the axis of chief interest, and a supply of oil was essential. The primary goal was to defend

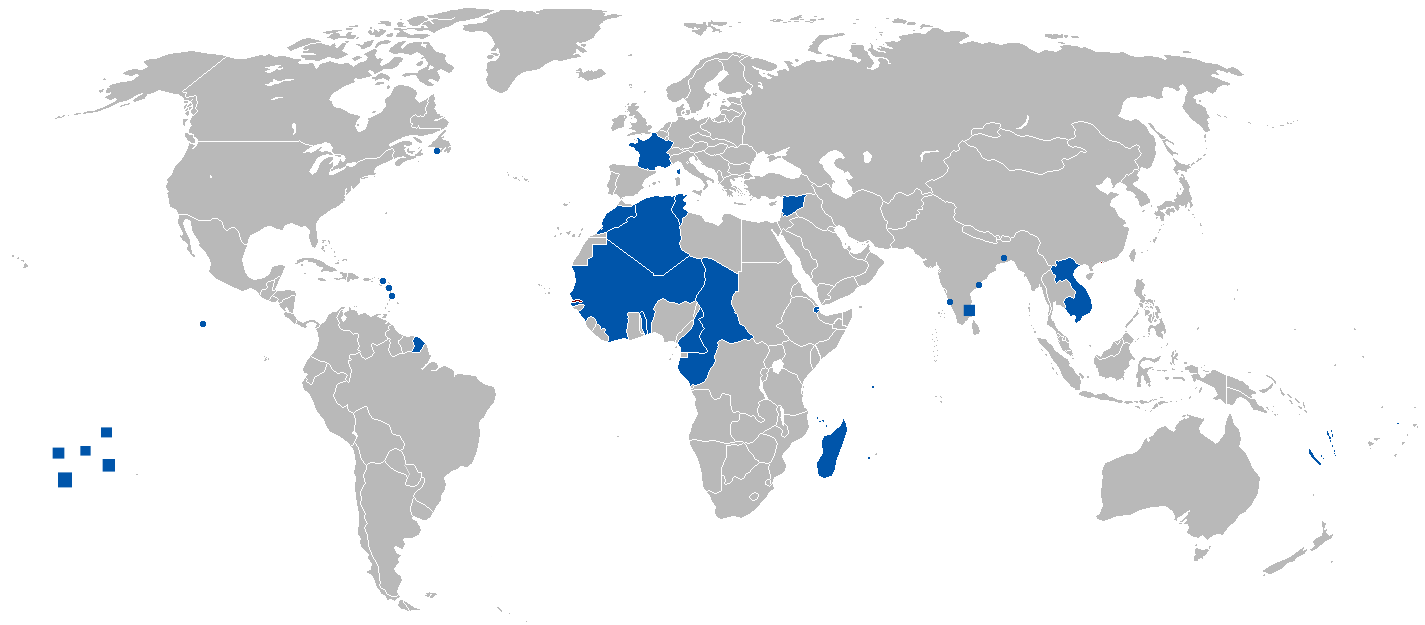

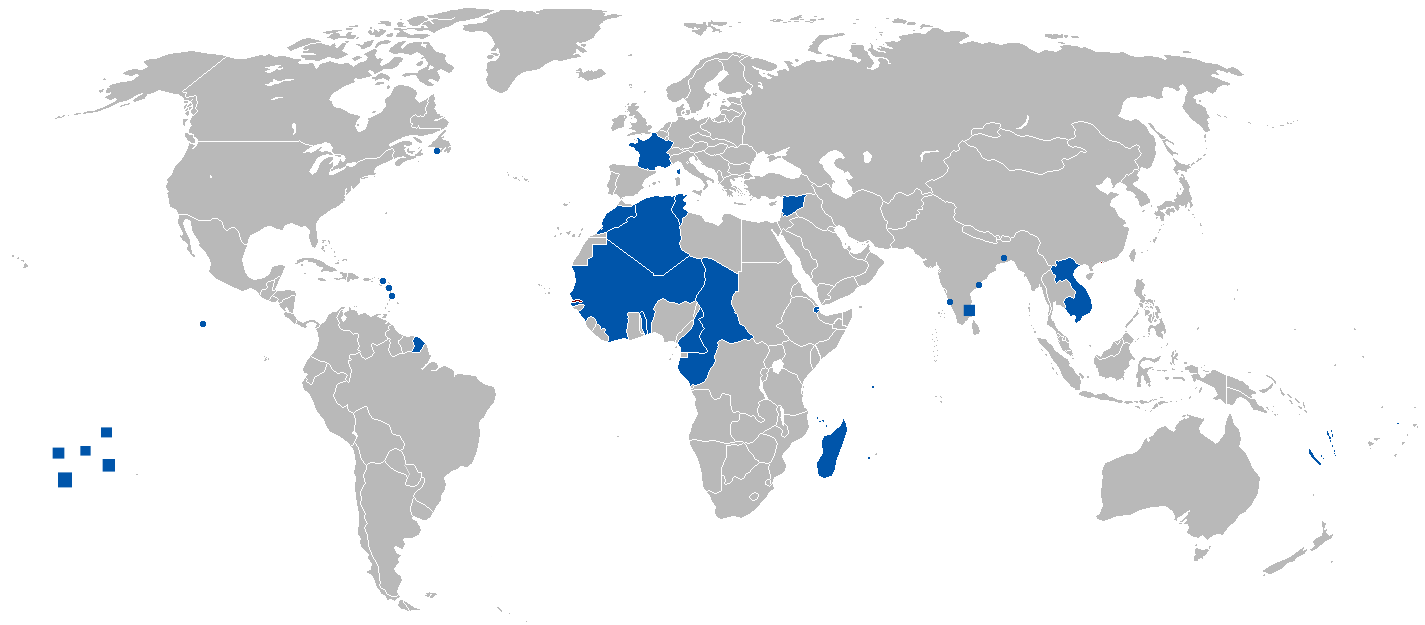

French North Africa

French North Africa (, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is a term often applied to the three territories that were controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In contrast to French ...

, and Briand made practical choices, for naval policy was a reflection of overall foreign policy. The Conference agreed on the American proposal that capital ships be limited to a ratio of 5 to 5 to 3 for the United States, Britain, and Japan, with Italy and France allocated 1.7 each. France's participation reflected its need to deal with its diminishing power and reduced human, material, and financial resources.

Briand's efforts to come to an agreement over reparations with the Germans failed in the wake of German intransigence. The immediate cause of Briand's forced resignation was a seemingly trivial incident during the

Cannes Conference of 1922. Pressured into a game of golf by David Lloyd George he played so badly that opposition factions in the National Assembly were able to portray him as both inept and a British sycophant. He was succeeded by the more bellicose

Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France. He was a conservative leader, primarily committed to ...

. In the wake of the

Ruhr Crisis, however, Briand's more conciliatory style became more acceptable, and he returned to the

Quai d'Orsay in 1925. He would remain foreign minister until his death in 1932. During this time, he was a member of 14 cabinets, four of which he headed himself in 1925–1926 and 1929.

Briand negotiated the

Briand-Ceretti Agreement with the Vatican, giving the French government a role in the appointment of Catholic bishops.

Kellogg–Briand Pact

Aristide Briand received the 1926

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

together with

Gustav Stresemann

Gustav Ernst Stresemann (; 10 May 1878 – 3 October 1929) was a German statesman during the Weimar Republic who served as Chancellor of Germany#First German Republic (Weimar Republic, 1919–1933), chancellor of Germany from August to November 1 ...

of Germany for the

Locarno Treaties

The Locarno Treaties, known collectively as the Locarno Pact, were seven post-World War I agreements negotiated amongst Germany, France, Great Britain, Belgium, Italy, Second Polish Republic, Poland and First Czechoslovak Republic, Czechoslovak ...

(

Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of ...

of the United Kingdom had received a share of the Peace Prize a year earlier for the same agreement).

A 1927 proposal by Briand and United States Secretary of State

Frank B. Kellogg for a universal pact outlawing war led the following year to the Pact of Paris, aka the

Kellogg–Briand Pact

The Kellogg–Briand Pact or Pact of Paris – officially the General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy – is a 1928 international agreement on peace in which signatory states promised not to use war t ...

.

Briand plan for European federation

As foreign minister Briand formulated an original proposal for a new economic union of Europe. Described as Briand's Locarno diplomacy and as an aspect of Franco-German rapprochement, it was his answer to Germany's quick economic recovery and future political power. Briand made his proposals in a speech in favor of a European Union in the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

on 5 September 1929, and in 1930, in his

Memorandum on the Organization of a Regime of European Federal Union for the Government of France.

The idea was to provide a framework to contain France's former enemy while preserving as much of the 1919 Versailles settlement as possible. The Briand plan entailed the economic collaboration of the great industrial areas of Europe and the provision of political security to Eastern Europe against Soviet threats. The basis was economic cooperation, but his fundamental concept was political, for it was political power that would determine economic choices. The plan, under the Memorandum on the Organization of a System of European Federal Union, was in the end presented as a French initiative to the League of Nations. With the death of his principal supporter, German foreign minister

Gustav Stresemann

Gustav Ernst Stresemann (; 10 May 1878 – 3 October 1929) was a German statesman during the Weimar Republic who served as Chancellor of Germany#First German Republic (Weimar Republic, 1919–1933), chancellor of Germany from August to November 1 ...

, and the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, Briand's plan was never adopted but it suggested an economic framework for developments after World War II that eventually resulted in the European Union.

[D. Weigall and P. Stirk, eds., ''The Origins and Development of the European Community'' (Leicester University Press, 1992), pp. 11–15 .]

Governments

Briand's first Government, 24 July 1909 – 3 November 1910

* Aristide Briand – President of the Council and Minister of the Interior and Worship

*

Stéphen Pichon – Minister of Foreign Affairs

*

Jean Brun – Minister of War

*

Georges Cochery – Minister of Finance

*

René Viviani – Minister of Labour and Social Security Provisions

*

Louis Barthou

Jean Louis Barthou (; 25 August 1862 – 9 October 1934) was a French politician of the French Third Republic, Third Republic who served as Prime Minister of France for eight months in 1913. In social policy, his time as prime minister saw the ...

– Minister of Justice

*

Auguste Boué de Lapeyrère – Minister of Marine

*

Gaston Doumergue – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

*

Joseph Ruau – Minister of Agriculture

*

Georges Trouillot – Minister of Colonies

*

Alexandre Millerand –

Minister of Public Works, Posts, and Telegraphs

*

Jean Dupuy – Minister of Commerce and Industry

Briand's second Government, 3 November 1910 – 2 March 1911

* Aristide Briand – President of the Council and Minister of the Interior and Worship

*

Stéphen Pichon – Minister of Foreign Affairs

*

Jean Brun – Minister of War

*

Louis Lucien Klotz – Minister of Finance

*

Louis Lafferre – Minister of Labour and Social Security Provisions

*

Théodore Girard – Minister of Justice

*

Auguste Boué de Lapeyrère – Minister of Marine

*

Maurice Faure – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

*

Maurice Raynaud – Minister of Agriculture

*

Jean Morel – Minister of Colonies

*

Louis Puech – Minister of Public Works, Posts, and Telegraphs

*

Jean Dupuy – Minister of Commerce and Industry

Changes

* 23 February 1911 – Briand succeeds Brun as interim Minister of War.

Briand's third and fourth Governments, 21 January – 22 March 1913

* Aristide Briand – President of the Council and Minister of the Interior

*

Charles Jonnart – Minister of Foreign Affairs

*

Eugène Étienne – Minister of War

*

Louis Lucien Klotz – Minister of Finance

*

René Besnard – Minister of Labour and Social Security Provisions

*

Louis Barthou

Jean Louis Barthou (; 25 August 1862 – 9 October 1934) was a French politician of the French Third Republic, Third Republic who served as Prime Minister of France for eight months in 1913. In social policy, his time as prime minister saw the ...

– Minister of Justice

*

Pierre Baudin – Minister of Marine

*

Théodore Steeg – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

*

Fernand David – Minister of Agriculture

*

Jean Morel – Minister of Colonies

*

Jean Dupuy – Minister of Public Works, Posts, and Telegraphs

*

Gabriel Guist'hau – Minister of Commerce and Industry

Briand's fifth Government, 29 October 1915 – 12 December 1916

* Aristide Briand – President of the Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs

*

Joseph Galliéni – Minister of War

*

Louis Malvy – Minister of the Interior

*

Alexandre Ribot – Minister of Finance

*

Albert Métin – Minister of Labour and Social Security Provisions

*

René Viviani – Minister of Justice

*

Lucien Lacaze – Minister of Marine

*

Paul Painlevé – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

*

Jules Méline – Minister of Agriculture

*

Gaston Doumergue – Minister of Colonies

*

Marcel Sembat – Minister of Public Works

*

Étienne Clémentel

Étienne Clémentel (; 11 January 1864 – 25 December 1936) was a French politician. He served as a member of the National Assembly of France from 1900 to 1919 and as French Senator from 1920 to 1936. He also served as Minister of Colonies fro ...

– Minister of Commerce, Industry, Posts, and Telegraphs

*

Léon Bourgeois – Minister of State

*

Denys Cochin – Minister of State

*

Émile Combes

Émile Justin Louis Combes (; 6 September 183525 May 1921) was a French politician and freemason who led the Bloc des gauches, Lefts Bloc (French: ''Bloc des gauches'') cabinet from June 1902 to January 1905.

Career

Émile Combes was born on 6 ...

– Minister of State

*

Charles de Freycinet – Minister of State

*

Jules Guesde

Jules Bazile, known as Jules Guesde (; 11 November 1845 – 28 July 1922) was a French socialist journalist and politician.

Guesde was the inspiration for a famous quotation by Karl Marx. Shortly before Marx died in 1883, he wrote a letter ...

– Minister of State

Changes

* 15 November 1915 –

Paul Painlevé becomes Minister of Inventions for the National Defense in addition to being Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts.

* 16 March 1916 –

Pierre Auguste Roques succeeds Galliéni as Minister of War

Briand's sixth Government, 12 December 1916 – 20 March 1917

* Aristide Briand – President of the Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs

*

Hubert Lyautey – Minister of War

*

Albert Thomas – Minister of Armaments and War Manufacturing

*

Louis Malvy – Minister of the Interior

*

Alexandre Ribot – Minister of Finance

*

Étienne Clémentel

Étienne Clémentel (; 11 January 1864 – 25 December 1936) was a French politician. He served as a member of the National Assembly of France from 1900 to 1919 and as French Senator from 1920 to 1936. He also served as Minister of Colonies fro ...

– Minister of Commerce, Industry, Labour, Social Security Provisions, Agriculture, Posts, and Telegraphs

*

René Viviani – Minister of Justice, Public Instruction, and Fine Arts

*

Lucien Lacaze – Minister of Marine

*

Édouard Herriot – Minister of Supply, Public Works, and Transport

*

Gaston Doumergue – Minister of Colonies

Changes

* 15 March 1917 –

Lucien Lacaze succeeds Lyautey as interim Minister of War.

Briand's seventh Government, 16 January 1921 – 15 January 1922

* Aristide Briand – President of the Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs

*

Louis Barthou

Jean Louis Barthou (; 25 August 1862 – 9 October 1934) was a French politician of the French Third Republic, Third Republic who served as Prime Minister of France for eight months in 1913. In social policy, his time as prime minister saw the ...

– Minister of War

*

Pierre Marraud – Minister of the Interior

*

Paul Doumer – Minister of Finance

*

Charles Daniel-Vincent – Minister of Labour

*

Laurent Bonnevay – Minister of Justice

*

Gabriel Guist'hau – Minister of Marine

*

Léon Bérard – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

*

André Maginot – Minister of War Pensions, Grants, and Allowances

*

Edmond Lefebvre du Prey – Minister of Agriculture

*

Albert Sarraut

Albert-Pierre Sarraut (; 28 July 1872 – 26 November 1962) was a French Radical politician, twice Prime Minister during the Third Republic.

Biography

Sarraut was born on 28 July 1872 in Bordeaux, Gironde, France.

On 14 March 1907 Sarraut ...

– Minister of Colonies

*

Yves Le Trocquer – Minister of Public Works

*

Georges Leredu – Minister of Hygiene, Welfare Work, and Social Security Provisions

*

Lucien Dior – Minister of Commerce and Industry

*

Louis Loucheur

Louis Loucheur (12 August 1872 in Roubaix, Nord – 22 November 1931 in Paris) was a French politician in the Third Republic, at first a member of the conservative Republican Federation, then of the Democratic Republican Alliance and of the I ...

– Minister of Liberated Regions

Briand's eighth Government, 28 November 1925 – 9 March 1926

* Aristide Briand – President of the Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs

*

Paul Painlevé – Minister of War

*

Camille Chautemps

Camille Chautemps (; 1 February 1885 – 1 July 1963) was a French Radical politician of the Third Republic, three times President of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister).

He was the father-in-law of U.S. politician and statesman Howar ...

– Minister of the Interior

*

Louis Loucheur

Louis Loucheur (12 August 1872 in Roubaix, Nord – 22 November 1931 in Paris) was a French politician in the Third Republic, at first a member of the conservative Republican Federation, then of the Democratic Republican Alliance and of the I ...

– Minister of Finance

*

Antoine Durafour – Minister of Labour, Hygiene, Welfare Work, and Social Security Provisions

*

René Renoult – Minister of Justice

*

Georges Leygues – Minister of Marine

*

Édouard Daladier – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

*

Paul Jourdain – Minister of Pensions

*

Jean Durand – Minister of Agriculture

*

Léon Perrier – Minister of Colonies

*

Anatole de Monzie – Minister of Public Works

*

Charles Daniel-Vincent – Minister of Commerce and Industry

Changes

* 16 December 1925 –

Paul Doumer succeeds Loucheur as Minister of Finance.

Briand's ninth Government, 9 March – 23 June 1926

* Aristide Briand – President of the Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs

*

Paul Painlevé – Minister of War

*

Louis Malvy – Minister of the Interior

*

Raoul Péret – Minister of Finance

*

Antoine Durafour – Minister of Labour, Hygiene, Welfare Work, and Social Security Provisions

*

Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. He served as Prime Minister of France three times: 1931–1932 and 1935–1936 during the Third Republic (France), Third Republic, and 1942–1944 during Vich ...

– Minister of Justice

*

Georges Leygues – Minister of Marine

*

Lucien Lamoureux – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

*

Paul Jourdain – Minister of Pensions

*

Jean Durand – Minister of Agriculture

*

Léon Perrier – Minister of Colonies

*

Anatole de Monzie – Minister of Public Works

*

Charles Daniel-Vincent – Minister of Commerce and Industry

Changes

* 10 April 1926 –

Jean Durand succeeds Malvy as Minister of the Interior.

François Binet succeeds Durand as Minister of Agriculture.

Briand's tenth Government, 23 June – 19 July 1926

* Aristide Briand – President of the Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs

*

Adolphe Guillaumat – Minister of War

*

Jean Durand – Minister of the Interior

*

Joseph Caillaux – Minister of Finance,

Vice President of the Council

*

Antoine Durafour – Minister of Labour, Hygiene, Welfare Work, and Social Security Provisions

*

Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. He served as Prime Minister of France three times: 1931–1932 and 1935–1936 during the Third Republic (France), Third Republic, and 1942–1944 during Vich ...

– Minister of Justice

*

Georges Leygues – Minister of Marine

*

Bertrand Nogaro – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

*

Paul Jourdain – Minister of Pensions

*

François Binet – Minister of Agriculture

*

Léon Perrier – Minister of Colonies

*

Charles Daniel-Vincent – Minister of Public Works

*

Fernand Chapsal – Minister of Commerce and Industry

Briand's eleventh Government, 29 July – 3 November 1929

* Aristide Briand – President of the Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs

*

Paul Painlevé –

Minister of War

A ministry of defence or defense (see American and British English spelling differences#-ce.2C -se, spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and Mi ...

*

André Tardieu –

Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

*

Henry Chéron –

Minister of Finance

*

Louis Loucheur

Louis Loucheur (12 August 1872 in Roubaix, Nord – 22 November 1931 in Paris) was a French politician in the Third Republic, at first a member of the conservative Republican Federation, then of the Democratic Republican Alliance and of the I ...

– Minister of Labour, Hygiene, Welfare Work, and Social Security Provisions

*

Louis Barthou

Jean Louis Barthou (; 25 August 1862 – 9 October 1934) was a French politician of the French Third Republic, Third Republic who served as Prime Minister of France for eight months in 1913. In social policy, his time as prime minister saw the ...

–

Minister of Justice

*

Georges Leygues – Minister of Marine

*

Laurent Eynac –

Minister of Air

*

Pierre Marraud –

Minister of Public Instruction and

Fine Arts

In European academic traditions, fine art (or, fine arts) is made primarily for aesthetics or creativity, creative expression, distinguishing it from popular art, decorative art or applied art, which also either serve some practical function ...

*

Louis Antériou – Minister of Pensions

*

Jean Hennessy –

Minister of Agriculture

*

André Maginot –

Minister of Colonies

*

Pierre Forgeot –

Minister of Public Works

*

Georges Bonnefous – Minister of Commerce and Industry

See also

*

Interwar France

*

List of people on the cover of ''Time'' magazine: 1920s

Notes

References

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Georges Suarez's multi-volume biography of Briand (1938–52) is of particular value to historians as it cites documents lost in 1940 (see Greenhalgh 2005, p. 288).

External links

*

Timeline for the 150th anniversary of Aristide Briand*

, -

{{DEFAULTSORT:Briand, Aristide

1862 births

1932 deaths

Politicians from Nantes

French Socialist Party (1902) politicians

Republican-Socialist Party politicians

French atheists

Prime ministers of France

Deputy prime ministers of France

Foreign ministers of France

European integration pioneers

French interior ministers

Ministers of justice of France

Ministers of war of France

Members of the 8th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

Members of the 9th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

Members of the 10th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

Members of the 11th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

Members of the 12th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

Members of the 13th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

Members of the 14th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

Members of Parliament for Loire

Members of Parliament for Loire-Atlantique

20th-century French diplomats

French Freemasons

French people of World War I

French Nobel laureates

Nobel Peace Prize laureates

World War I politicians

Briand returned to power in 1921. He supervised the French role in the Washington Naval Conference of 1921–22. Three factors guided the French strategy and necessitated a Mediterranean focus: the French navy needed to carry a great many goods, the Mediterranean was the axis of chief interest, and a supply of oil was essential. The primary goal was to defend

Briand returned to power in 1921. He supervised the French role in the Washington Naval Conference of 1921–22. Three factors guided the French strategy and necessitated a Mediterranean focus: the French navy needed to carry a great many goods, the Mediterranean was the axis of chief interest, and a supply of oil was essential. The primary goal was to defend

Aristide Briand received the 1926

Aristide Briand received the 1926