Architecture Of Slovenia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The architecture of Slovenia has a long, rich and diverse history.

Modern architecture in Slovenia was introduced by Max Fabiani, and in the mid-war period, Jože Plečnik and Ivan Vurnik. In the second half of the 20th century, the national and universal style were merged by the architects Edvard Ravnikar and Marko Mušič.

Around 50 BC, the Ancient Rome, Romans built a military encampment that later became a permanent settlement called Emona, Iulia Aemona. This entrenched fort was occupied by the ''Legio XV Apollinaris''. Hildegard Temporini-Gräfin Vitzthum, Hildegard Temporini and Wolfgang Haase, ''Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt''. de Gruyter, 1988.

Around 50 BC, the Ancient Rome, Romans built a military encampment that later became a permanent settlement called Emona, Iulia Aemona. This entrenched fort was occupied by the ''Legio XV Apollinaris''. Hildegard Temporini-Gräfin Vitzthum, Hildegard Temporini and Wolfgang Haase, ''Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt''. de Gruyter, 1988.

Google Books, p.343

/ref> In 452, it was destroyed by the Huns under Attila the Hun, Attila's orders, and later by the Ostrogoths and the Lombards.Daniel Mallinus, ''La Yougoslavie'', Éd. Artis-Historia, Brussels, 1988, D/1988/0832/27, p. 37-39. Emona housed 5,000–6,000 inhabitants and played an important role during numerous battles. Its plastered brick houses, painted in different colours, were already connected to a Sewage, drainage system.

After the 1511 Idrija earthquake, Ljubljana was rebuilt in the Renaissance architecture, Renaissance style. Wooden buildings were forbidden after a large fire at New Square in 1524.

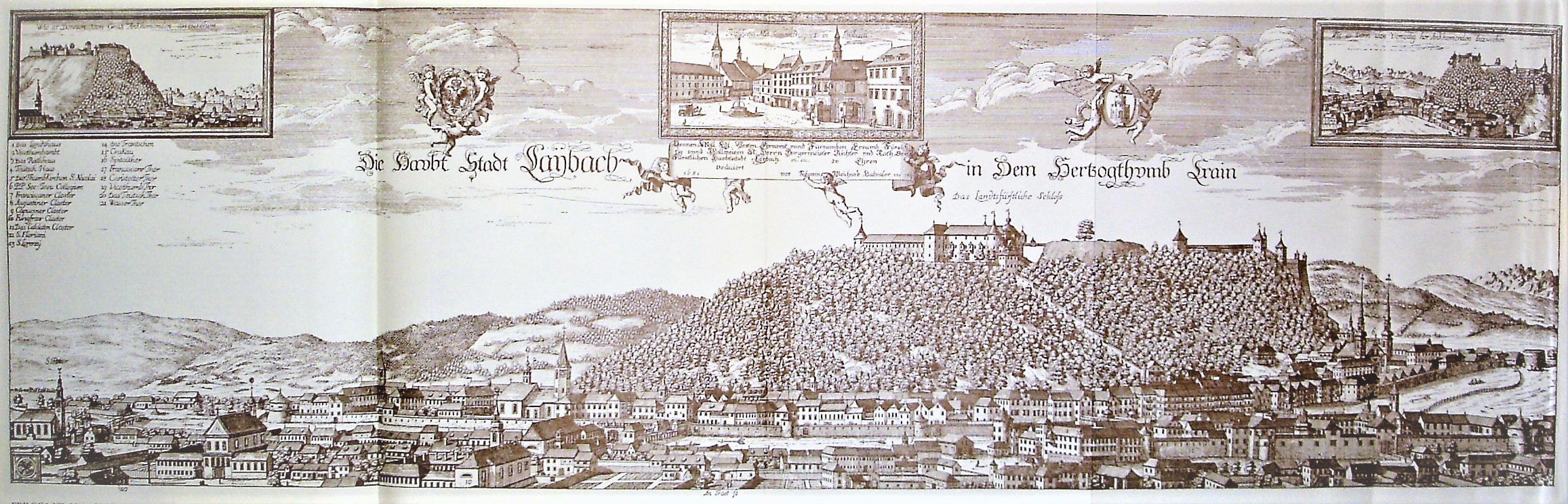

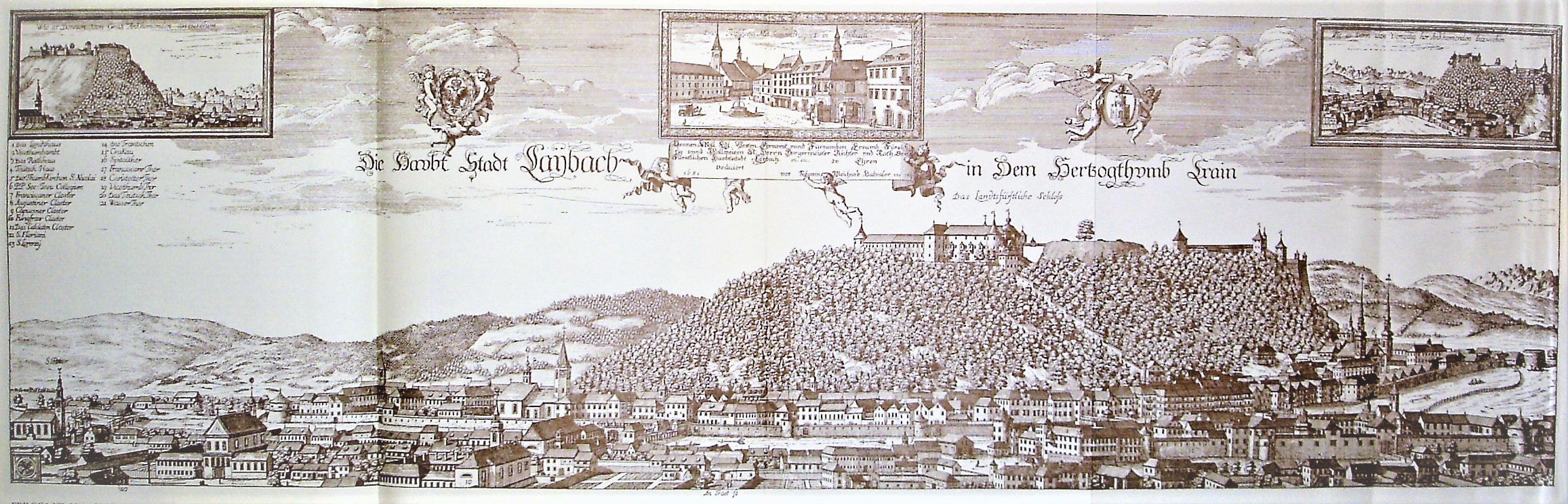

With the Counter-Reformation, in the middle and the second half of the 17th century, foreign architects built and renovated numerous monasteries, churches, and palaces in Ljubljana and introduced Baroque architecture

After the 1511 Idrija earthquake, Ljubljana was rebuilt in the Renaissance architecture, Renaissance style. Wooden buildings were forbidden after a large fire at New Square in 1524.

With the Counter-Reformation, in the middle and the second half of the 17th century, foreign architects built and renovated numerous monasteries, churches, and palaces in Ljubljana and introduced Baroque architecture

File:Pristanišče na Bregu 1765.jpg, Ljubljana in the 18th century

File:Leander Russ - Parade zur Begrüßung des Kaisers in Laibach - 1845.jpeg, Celebration during the Congress of Laibach, 1821

File:Špitalski most, Marijin trg in pogled proti Šmarni gori z gradu 1900.jpg, Ljubljana, c. 1900

Ljubljana - Gornji trg 13.jpg, Gornji trg 13

Ljubljana - Boscheva hiša (Ribji trg 2).jpg, Bosch House, the oldest dated house in Ljubljana. It stands at Fish Square (Ribji trg) 2 and dates to 1528. In 1562, the Protestant reformer Primož Trubar lived here.

Ljubljana (Mestni trg 9) - Lichtenbergova hiša (pročelje).jpg , Lichtenberg House at 9 Town Square in Ljubljana, a Renaissance bourgeois house with a Baroque staircase from the 18th century and an early-Baroque facade from 1540, decorated with reliefs by the sculptor Osbald Kitell.

CekinovGrad-Ljubljana.JPG, ''Cekinov Grad'', a late-Baroque mansion in Tivoli City Park in Ljubljana

Ljubljana City Museum (48701433533).jpg, Turjak Palace, a Baroque aristocratic corner building from the mid-17th century; the neo-Classicist facade dates to the 19th century. The main building of the City Museum of Ljubljana

Mladina, 12 August 2010 Fabiani's first large-scale architectural project was the urban plan for the Carniolan, now Slovenian capital Ljubljana, which was badly damaged by the April 1895 Ljubljana earthquake. Fabiani won a competition against the more historicist architect Camillo Sitte, and was chosen by the Ljubljana Town Council as the main urban planner. One of the reasons for this choice was Fabiani was considered by the National Progressive Party (Slovenia), Slovene Liberal Nationalists as a Slovenes, Slovene. Second reason was that he knew Ljubljana better than Sitte and prepared really good and modern plan. With the personal sponsorship of the Liberal nationalist mayor of Ljubljana Ivan Hribar, Fabiani designed several important buildings in the town, including the L-shaped school in the Mladika Complex facing Prešeren Street (), which is now the seat of the Slovenian Foreign Ministry. Max Fabiani also designed Prešeren Square as the hub of four streets. In place of the medieval houses which were damaged by the earthquake, a number of palaces were built around it. Between Wolf Street and Čop Street stands the Hauptmann House, built in 1873 and renovated in 1904 in the Secessionist style by the architect Ciril Metod Koch. The other palaces include the Frisch House, the Seunig House and the Urbanc House, as well as the Mayer department store, built thirty years later.

File:Winter is back! (16383877756).jpg, Neo-renaissance Villa Samassa, 1871

File:Slovenia - Ljubljana - panoramio.jpg, Neo-renaissance Central Post Office in Ljubljana, built from 1895-1896 by Supančič and Knez according to plans by Friedrich Setz (1837-1907). Stonemasonry works were carried out by Feliks Toman (1855-1939).

File:Ljubljana (5746742826).jpg, Villa Wettach, by Alfred Bayer, 1897, today U.S. Embassy

File:Frankopanska cesta, nekdanja gostilna Reininghaus (4575910564).jpg, Reininghouse, 1903

File:Laibach (14097864343).jpg, House at Dalmatinska by Robert Smielowsky, 1903

File:Tavčar Street No. 4, Ljubljana.jpg, House by Ciril Metod Koch at Tavčar Street 4, 1903

File:Ljubljana BW 2014-10-09 12-22-15.jpg, Hauptmann Building (), a.k.a. the Little Skyscraper (), on Ljubljana's Prešeren Square, renovated in the Vienna Secession style by Ciril Metod Koch in 1904

File:03 2019 photo Paolo Villa - F0197804 - Lubiana - Piazza triplo ponte - casa - Secessione viennese Liberty.jpg,

Nova Gorica, the train station..jpg, Nova Gorica Train Station by Robert Seelig, 1906

Murska Sobota Zvesda Hotel 2015.JPG, Zvezda Hotel in Murska Sobota, 1908

File:Radovljica - hiša Čebelica.jpg, Čebelica house in Radovljica by Ciril Metod Koch

File:15-11-25-Maribor Inenstadt-RalfR-WMA 4252.jpg, ''Velika kavarna'' in Maribor

(In Slovene: ''"Vurnikova hiša na Miklošičevi: najlepša hiša v Ljubljani"''), Delo (newspaper), Delo, 8 April 2011Arhitekturno-slikarski dvojec: Ivan Vurnik in Helena Kottler Vurnik

(Dokumentarno-igrani film TV Slovenija), MMC RTV Slovenia, 8 February 2013 Beginning with the late 1920s and 1930s, Yugoslav architects including Vurnik and Plečnik began to advocate for Modern architecture, architectural modernism and Functionalism (architecture), functionalist, viewing the style as the logical extension of progressive national narratives. Jože Plečnik gave Ljubljana its modern identity by designing iconic buildings such as the National and University Library of Slovenia, Slovene National and University Library building. He also designed other notable buildings, including the Vzajemna Insurance Company Offices, and contributed to many civic improvements. He renovated the city's bridges and the Ljubljanica banks, and designed the Ljubljana Central Market and the Žale cemetery.

Modern and contemporary Slovene architecture. www.culturalprofiles.org.uk 2007

(Archived by WebCite®) Ravnikar, a professor at the Ljubljana School of Architecture, promoted Scandinavian architectural style in Slovenia, particularly Finnish achievements in architecture accomplished by those such as Alvar Aalto. His most notable creations feature prominently in Ljubljana, among them Republic Square, Ljubljana, Republic Square, Cankar Hall, Maximarket department store, and the Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana, Museum of Modern Art.

Prehistory and Antiquity

Around 2000 BC, the Ljubljana Marsh in the immediate vicinity of Ljubljana were settled by people living in stilt house, pile dwellings. Prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps, Prehistoric pile dwellings and Ljubljana Marshes Wooden Wheel, the oldest wooden wheel in the world are among the most notable archeological findings from the marshland. These Pile-dwelling culture of the Ljubljana Marshes, lake-dwelling people lived through hunting, fishing and primitive agriculture. To get around the marsh, they used dugout canoes made by cutting out the inside of tree trunks. Their archaeological remains, nowadays in the Municipality of Ig, have been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site since June 2011, in the Prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps, common nomination of six Alpine states.Google Books, p.343

/ref> In 452, it was destroyed by the Huns under Attila the Hun, Attila's orders, and later by the Ostrogoths and the Lombards.Daniel Mallinus, ''La Yougoslavie'', Éd. Artis-Historia, Brussels, 1988, D/1988/0832/27, p. 37-39. Emona housed 5,000–6,000 inhabitants and played an important role during numerous battles. Its plastered brick houses, painted in different colours, were already connected to a Sewage, drainage system.

Medieval period and early modernity

After the 1511 Idrija earthquake, Ljubljana was rebuilt in the Renaissance architecture, Renaissance style. Wooden buildings were forbidden after a large fire at New Square in 1524.

With the Counter-Reformation, in the middle and the second half of the 17th century, foreign architects built and renovated numerous monasteries, churches, and palaces in Ljubljana and introduced Baroque architecture

After the 1511 Idrija earthquake, Ljubljana was rebuilt in the Renaissance architecture, Renaissance style. Wooden buildings were forbidden after a large fire at New Square in 1524.

With the Counter-Reformation, in the middle and the second half of the 17th century, foreign architects built and renovated numerous monasteries, churches, and palaces in Ljubljana and introduced Baroque architecture

Art Nouveau and Secession style

During the reconstruction that followed the 1895 Ljubljana earthquake, a number of districts were rebuilt in the Vienna Secession style. Public Incandescent light bulb, electric lighting appeared in the city in 1898. The rebuilding period between 1896 and 1910 is referred to as the "revival of Ljubljana" because of architectural changes from which a great deal of the city dates back to today and for reform of urban administration, health, education and tourism that followed. The rebuilding and quick modernisation of the city were led by the mayor Ivan Hribar. Together with Ciril Metod Koch and Ivan Vancaš, Max Fabiani introduced the Vienna Secession style of architecture (a type of Art Nouveau) in Slovenia.Andrej Hrausky, Janez Koželj: ''Maks Fabiani: Dunaj, Ljubljana, Trst.''Mladina, 12 August 2010 Fabiani's first large-scale architectural project was the urban plan for the Carniolan, now Slovenian capital Ljubljana, which was badly damaged by the April 1895 Ljubljana earthquake. Fabiani won a competition against the more historicist architect Camillo Sitte, and was chosen by the Ljubljana Town Council as the main urban planner. One of the reasons for this choice was Fabiani was considered by the National Progressive Party (Slovenia), Slovene Liberal Nationalists as a Slovenes, Slovene. Second reason was that he knew Ljubljana better than Sitte and prepared really good and modern plan. With the personal sponsorship of the Liberal nationalist mayor of Ljubljana Ivan Hribar, Fabiani designed several important buildings in the town, including the L-shaped school in the Mladika Complex facing Prešeren Street (), which is now the seat of the Slovenian Foreign Ministry. Max Fabiani also designed Prešeren Square as the hub of four streets. In place of the medieval houses which were damaged by the earthquake, a number of palaces were built around it. Between Wolf Street and Čop Street stands the Hauptmann House, built in 1873 and renovated in 1904 in the Secessionist style by the architect Ciril Metod Koch. The other palaces include the Frisch House, the Seunig House and the Urbanc House, as well as the Mayer department store, built thirty years later.

Royalist Yugoslav period

architecture of Yugoslavia, Yugoslav architecture emerged in the first decades of the 20th century before the Creation of Yugoslavia, establishment of the state; during this period a number of South Slavic creatives, enthused by the possibility of statehood, organized a series of art exhibitions in Serbia in the name of a shared Slavic identity. Following governmental centralization after the 1918 creation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, this initial bottom-up enthusiasm began to fade. Yugoslav architecture became more dictated by an increasingly concentrated state authority which sought to establish a unified state identity. In 1919, Ivan Vurnik and Jože Plečnik founded the Ljubljana School of Architecture. The 1920s decade is associated with the search for a Slovene culture, Slovene "National Style", inspired by Slovene folk art and the Vienna Secession style. The Cooperative Business Bank Building (Ljubljana), Cooperative Business Bank, designed by Vurnik and his wife Helena Kottler Vurnik who designed the decorative facade in the colors of Slovene tricolor, has been called the most beautiful building in Ljubljana.The Most Beautiful House in Ljubljana(In Slovene: ''"Vurnikova hiša na Miklošičevi: najlepša hiša v Ljubljani"''), Delo (newspaper), Delo, 8 April 2011Arhitekturno-slikarski dvojec: Ivan Vurnik in Helena Kottler Vurnik

(Dokumentarno-igrani film TV Slovenija), MMC RTV Slovenia, 8 February 2013 Beginning with the late 1920s and 1930s, Yugoslav architects including Vurnik and Plečnik began to advocate for Modern architecture, architectural modernism and Functionalism (architecture), functionalist, viewing the style as the logical extension of progressive national narratives. Jože Plečnik gave Ljubljana its modern identity by designing iconic buildings such as the National and University Library of Slovenia, Slovene National and University Library building. He also designed other notable buildings, including the Vzajemna Insurance Company Offices, and contributed to many civic improvements. He renovated the city's bridges and the Ljubljanica banks, and designed the Ljubljana Central Market and the Žale cemetery.

Socialist Yugoslav period

The architecture of Yugoslavia was characterized by emerging, unique, and often differing national and regional narratives. As a socialist state remaining free from the Iron Curtain, Yugoslavia adopted a hybrid identity that combined the architectural, cultural, and political leanings of both Western liberal democracy and Soviet communism. Immediately following the Second World War, Yugoslavia's brief association with the Eastern Bloc ushered in a short period of socialist realism. Centralization within the communist model led to the abolishment of private architectural practices and the state control of the profession. During this period, the governing League of Communists of Yugoslavia, Communist Party condemned modernism as "bourgeois formalism," a move that caused friction among the nation's pre-war modernist architectural elite. Despite being a fervent Catholic, in 1947 Jože Plečnik was invited to design a new Parliament building. Plečnik proposed the ''Cathedral of Freedom'' where he wanted to raze the Ljubljana Castle and to build a monumental octagonal building instead. The unrealized Plečnik Parliament is featured on the Slovene Plečnik Parliament#Cultural significance, 10 cent euro coin socialist realism, Socialist realist architecture in Yugoslavia came to an abrupt end with Josip Broz Tito's 1948 Tito–Stalin Split, split with Stalin. In the following years the nation turned increasingly to the West, returning to the modernism that had characterized pre-war Yugoslav architecture. During this era, modernist architecture came to symbolize the nation's break from the USSR (a notion that later diminished with growing acceptability of modernism in the Eastern Bloc). During this period, the Yugoslav break from Soviet socialist realism combined with efforts to commemorate World War II, which together led to the creation of an immense quantity of abstract sculptural war memorials, known today as Yugoslav World War II monuments and memorials, ''spomenik'' In the late 1950s and early 1960s Brutalist architecture, Brutalism began to garner a following within Yugoslavia, particularly among younger architects, a trend possibly influenced by the 1959 disbandment of the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne. With 1950s decentralization and liberalization policies in Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, SFR Yugoslavia, architecture became increasingly fractured along ethnic lines. Architects increasingly focused on building with reference to the architectural heritage of their individual socialist republics in the form of critical regionalism. Growing distinction of individual ethnic architectural identities within Yugoslavia was exacerbated with the 1972 decentralization of the formerly centralized historical preservation authority, providing individual regions further opportunity to critically analyze their own cultural narratives. The next generation of Slovenian architects was led by Novo Mesto-born Edvard Ravnikar, student of Jože Plečnik.(Archived by WebCite®)

Contemporary period

The international style, which had arrived in Yugoslavia already in the 1980s, took over the scene after the independence.See also

References

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Architecture Of Slovenia Architecture in Slovenia, Cultural history of Slovenia