Archibald Roosevelt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Archibald Bulloch Roosevelt Sr. (April 9, 1894 – October 13, 1979) was a U.S. Army officer and commander of U.S. forces in World War I and II, and the fifth child of U.S. President

Archie was born in Washington, D.C., the fourth child of President Theodore "T. R." Roosevelt Jr. and Edith Kermit Carow. He had three brothers, Ted (Theodore III), Kermit, and Quentin, a sister Ethel, and a half-sister

Archie was born in Washington, D.C., the fourth child of President Theodore "T. R." Roosevelt Jr. and Edith Kermit Carow. He had three brothers, Ted (Theodore III), Kermit, and Quentin, a sister Ethel, and a half-sister

Archie volunteered for the

Archie volunteered for the

After United States' entry into World War II on the side of the

After United States' entry into World War II on the side of the

Chapter 7. The Fight for Komiatum

The Australian War Memorial

TOC

) On August 12, 1943, Roosevelt was wounded by an enemy grenade, which shattered the same knee that had been injured in World War I, and for which he had been earlier medically retired, earning him the distinction of being the only American to ever be classified as 100% disabled twice for the same wound incurred in two different wars. At the time of his injury, command of his battalion passed to his executive officer, Major Taylor. Archie returned to his unit in early 1944. For these actions in the Pacific Theater of Operations, Roosevelt was awarded his second and third oak leaf clusters to the

Red Intrigue and Race Turmoil

'' Foreword by Archibald B. Roosevelt.

The Great Deceit: Social Pseudo-Sciences

'' Foreword by Archibald B. Roosevelt. Sayville, NY: Veritas Publishing, 1964.

Quentin and his brother Archie and their father Theodore Roosevelt on film during World War I

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20070304071033/http://www.roosevelt-cross.com/home/index.php Roosevelt & Cross

U.S. Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific – Operation Cartwheel, The Reduction of Rabaul, New Guinea, US Army War College

{{DEFAULTSORT:Roosevelt, Archibald 1894 births 1979 deaths Military personnel from Washington, D.C. American people of Dutch descent United States Army personnel of World War I United States Army personnel of World War II American people of Scotch-Irish descent American people of Scottish descent Bulloch family Harvard University alumni Archibald Bulloch Roosevelt Schuyler family United States Army colonels Recipients of the Silver Star American recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) American segregationists John Birch Society members American conspiracy theorists Sidwell Friends School alumni Ritchie Boys Children of Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

. In both conflicts he was wounded. He earned the Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against a ...

with three oak leaf cluster

An oak leaf cluster is a ribbon device to denote preceding decorations and awards consisting of a miniature bronze or silver twig of four oak leaves with three acorns on the stem. It is authorized by the United States Armed Forces for a spec ...

s, Purple Heart

The Purple Heart (PH) is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the president to those wounded or killed while serving, on or after 5 April 1917, with the U.S. military. With its forerunner, the Badge of Military Merit, ...

with oak leaf cluster, and the French Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

. After World War II, he became a businessman and the founder of a New York City bond brokerage house, as well as a spokesman for conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

political causes.

Early life and family

Archie was born in Washington, D.C., the fourth child of President Theodore "T. R." Roosevelt Jr. and Edith Kermit Carow. He had three brothers, Ted (Theodore III), Kermit, and Quentin, a sister Ethel, and a half-sister

Archie was born in Washington, D.C., the fourth child of President Theodore "T. R." Roosevelt Jr. and Edith Kermit Carow. He had three brothers, Ted (Theodore III), Kermit, and Quentin, a sister Ethel, and a half-sister Alice

Alice may refer to:

* Alice (name), most often a feminine given name, but also used as a surname

Literature

* Alice (''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''), a character in books by Lewis Carroll

* ''Alice'' series, children's and teen books by ...

. Archie was named for his maternal great-great-great-grandfather Archibald Bulloch, a patriot of the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

.

His first cousin was Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt ( ; October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the longest-serving First Lady of the United States, first lady of the United States, during her husband Franklin D ...

and his fifth cousin, once removed was Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

. He was uncle to Kermit Roosevelt Jr., Joseph Willard Roosevelt, Dirck Roosevelt, Belle Wyatt "Clochette" Roosevelt, Grace Green Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt III, Cornelius V.S. Roosevelt, and Quentin Roosevelt II. His sister-in-law was Belle Wyatt Willard Roosevelt, and his grandniece was Susan Roosevelt Weld, the former wife of Massachusetts Governor William F. Weld.

As a child, Archie was very quiet but very mischievous – especially when he was with his brother Quentin; growing up, Archie and Quentin were very close. They rarely left each other's side and had very few fights. But as for the other siblings, Archie was not close to either Kermit or Ethel, because they would gang up on him. Ted would help beat up Kermit for him and would also tell their mother, Edith, about Ethel, who would often get in trouble. Alice was ten years older than Archie, and he barely remembered her being around, since she would often go places with other family members and friends. Archie was an avid reader and very good at putting puzzles together quickly. His father remarked to him, "Archie, my smart boy, never give up your smartness; that goes for you and your brother Quentin."

Archie first attended the Force School and Sidwell Friends School.

After being expelled from Groton, Archie continued his education at the Evans School for Boys,Theodore Roosevelt (1916) A Book-Lover's Holidays in the Open. New York: Charles Scribner's sons. and graduated from Phillips Academy

Phillips Academy (also known as PA, Phillips Academy Andover, or simply Andover) is a Private school, private, Mixed-sex education, co-educational college-preparatory school for Boarding school, boarding and Day school, day students located in ...

, Andover, Massachusetts

Andover is a town in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. It was Settler, settled in 1642 and incorporated in 1646."Andover" in ''Encyclopedia Britannica, The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th ed. ...

, in 1913. He went on to Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

, where he graduated in 1917.

Military career

World War I and years later

Archie volunteered for the

Archie volunteered for the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

during 1917, shipped over to France, and was wounded while serving with the U.S. 1st Infantry Division

The 1st Infantry Division (1ID) is a Armored brigade combat team, combined arms Division (military), division of the United States Army, and is the oldest continuously serving division in the Regular Army (United States), Regular Army. It has ...

. His wounds were so severe he was discharged from the Army with full disability. He had ended the war as an Army captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

. For his valor, Archie received two Silver Star Citations (later converted to the Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against a ...

medal when it was established in 1932) and the French government's Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

.

After the death of his father in 1919, he sent a telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas pi ...

informing all his siblings that "the old lion is dead".

After the end of the war, he worked for a time as an executive with the Sinclair Consolidated Oil Company, as vice president of the Union Petroleum Company, the export auxiliary subsidiary of Sinclair Consolidated. At the same time his eldest brother Ted was Assistant Secretary of the Navy. In 1922, Albert B. Fall

Albert Bacon Fall (November 26, 1861November 30, 1944) was a United States senator from New Mexico and United States Secretary of the Interior, Secretary of the Interior under President of the United States, President Warren G. Harding who becam ...

, U.S. Secretary of the Interior, leased, without competitive bidding, the Teapot Dome Field to Harry F. Sinclair of Sinclair Oil, and the field at Elk Hills, California, to Edward L. Doheny of Pan American Petroleum & Transport Company, both fields part of the Navy's petroleum reserves. The connection between the Roosevelt brothers could not be ignored. After Sinclair sailed for Europe to avoid testifying, G. D. Wahlberg, Sinclair's private secretary, advised Archibald Roosevelt to resign to save his reputation. Eventually, after resigning from Sinclair, Roosevelt gave key testimony to the Senate Committee on Public Lands probing the Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a political corruption scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Warren G. Harding. It centered on Interior Secretary Albert B. Fall, who had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Do ...

, in which Roosevelt was not implicated, but where Sinclair and Doheny both gave "personal loans" to Secretary Fall. Following this, Roosevelt took a job working for a cousin in the family investment firm, Roosevelt & Son.

In the summer of 1932, Archie, former President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

, former Solicitor General William Marshall Bullitt, Admiral Richard E. Byrd, and General James Harbord, among others, formed a conservative pressure group known as the National Economy League, which called for balancing the federal budget by cutting appropriations for veterans in half.

World War II: The Battle for Roosevelt Ridge in New Guinea

After United States' entry into World War II on the side of the

After United States' entry into World War II on the side of the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

following the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

, Roosevelt petitioned President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

to put his battlefield-honed leadership skills to worthwhile use for the American war effort. The president approved his request and he rejoined the Army with a commission as a Major. Roosevelt was given command in early 1943 of the US Army's 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry Regiment also called the 162 Regimental Combat Team, (RCT), 41st Infantry Division in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

commanding this unit until early 1944. Working with the Australian 3rd Division, Roosevelt and his battalion landed in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

's Nassau Bay, on July 8, 1943.

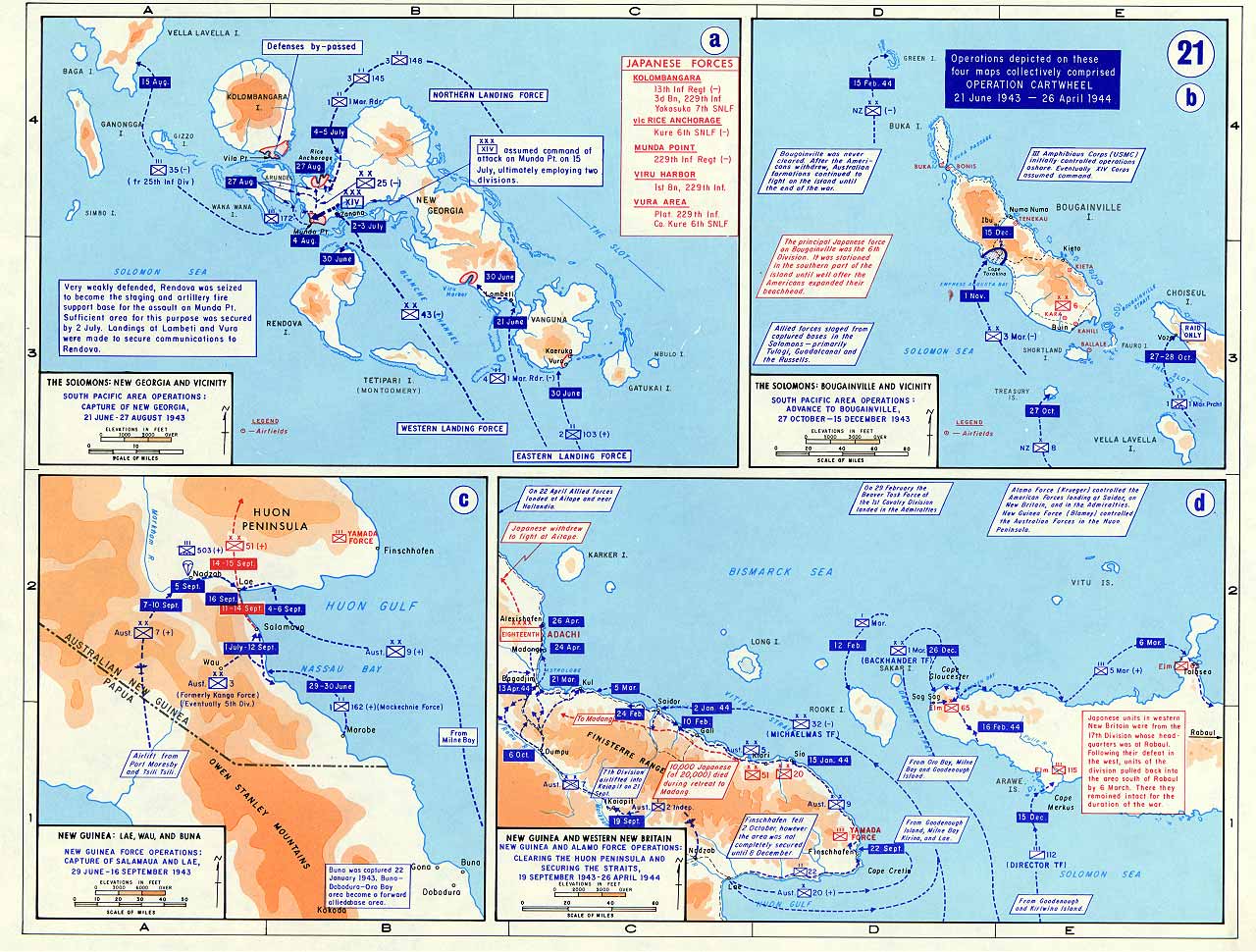

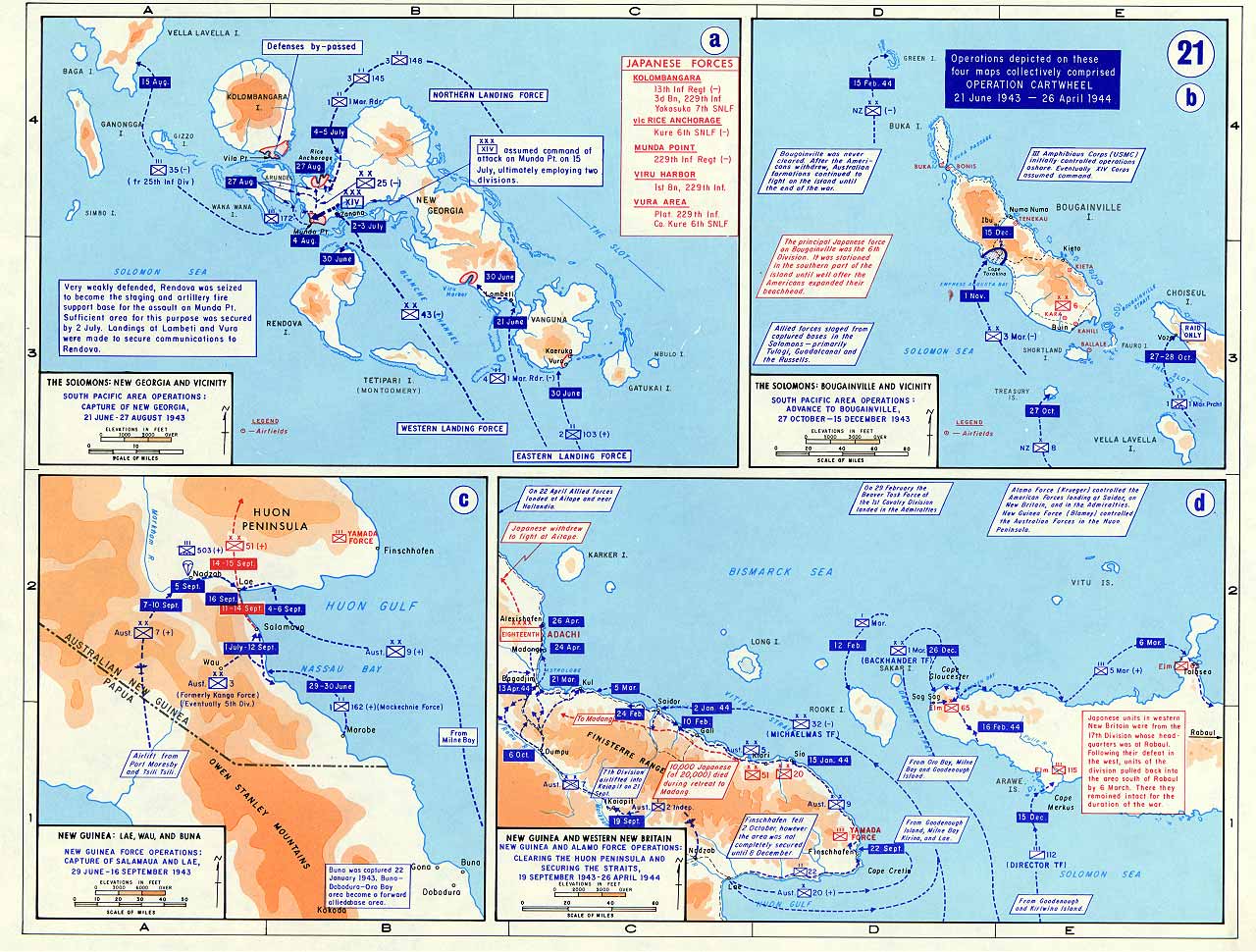

Overcoming significant command ambiguities between American and Australian forces because of overlapping spheres of operation, Roosevelt played an important role in the Salamaua campaign. His service was recognized when one of the hotly contested ridge-lines northwest of the island's Tambu Bay was named in his honor. This piece of key terrain during the campaign was originally referred to as "Roosevelt's Ridge" to mark the ridge nearest his battalion to higher HQ. Later, it was referred to as "Roosevelt Ridge" as it was depicted in the official American and Australian campaign histories as well as the US Army Air Force World War II Chronology. See left map.David Dexter (1961) Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army – Volume Chapter 7. The Fight for Komiatum

The Australian War Memorial

TOC

) On August 12, 1943, Roosevelt was wounded by an enemy grenade, which shattered the same knee that had been injured in World War I, and for which he had been earlier medically retired, earning him the distinction of being the only American to ever be classified as 100% disabled twice for the same wound incurred in two different wars. At the time of his injury, command of his battalion passed to his executive officer, Major Taylor. Archie returned to his unit in early 1944. For these actions in the Pacific Theater of Operations, Roosevelt was awarded his second and third oak leaf clusters to the

Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against a ...

in lieu of additional awards.

Military awards

*Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against a ...

with three oak leaf clusters

* Bronze Star Medal

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious a ...

* Purple Heart

The Purple Heart (PH) is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the president to those wounded or killed while serving, on or after 5 April 1917, with the U.S. military. With its forerunner, the Badge of Military Merit, ...

with oak leaf cluster

* World War I Victory Medal

* Army of Occupation of Germany Medal

* American Defense Service Medal

The American Defense Service Medal was a United States service medals of the World Wars, military award of the United States Armed Forces, established by , by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on June 28, 1941.

The medal was intended to recogniz ...

* American Campaign Medal

The American Campaign Medal was a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on November 6, 1942, by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was intended to recognize those military members who had per ...

* Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with one campaign star

* World War Two Victory Medal

* Army of Occupation Medal

* French Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

1914–1918

Later career

Entrepreneurship in the Investment Sector

Following the end of the war, Archie Roosevelt formed the investment firm of Roosevelt and Cross, a brokerage house specializing in municipal bonds. It is still a going concern with offices inNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, Providence, Buffalo and Hartford.

Activism and controversies

During the early 1950s, Archie became affiliated with a variety of right-wing organizations and causes. He joined theJohn Birch Society

The John Birch Society (JBS) is an American right-wing political advocacy group. Founded in 1958, it is anti-communist, supports social conservatism, and is associated with ultraconservative, radical right, far-right, right-wing populist, and ...

and was the founder of the Veritas Foundation, which was dedicated to rooting out presumed socialist influences at Harvard and other major colleges and universities. Writing in the book ''America's Political Dynasties'' (Doubleday, 1966), Stephen Hess commented: "Archie Roosevelt has, in recent years, added the family's name to many ultra-rightist causes. As a trustee of the Veritas Foundation he was a leader among those seeking to root out subversion at Harvard. He also sent a letter to every U.S. Senator, stating 'modern technical civilization does not seem to be as well-handled by the black man as by the white man in the United States.' Present civil rights difficulties he blamed on 'socialist plotters.'" Roosevelt also compiled 1968's incendiary ''Theodore Roosevelt On Race, Riots, Reds, Crime.'' He was also the chief sponsor behind "The Alliance," a short-lived organization of the 1950s.

In 1953 he joined the Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

The Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), formally the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (NSSAR), is a federally chartered patriotic organization. The National Society, a nonprofit corporation headquartered in Louisvi ...

of which both his father and elder brother had been members.

In 1954, when the Theodore Roosevelt Association made a decision to award the Theodore Roosevelt Medal for Distinguished Public Service to black diplomat Ralph Bunche

Ralph Johnson Bunche ( ; August 7, 1904 – December 9, 1971) was an American political scientist, diplomat, and leading actor in the mid-20th-century decolonization process and US civil rights movement, who received the 1950 Nobel Peace Priz ...

, Archie loudly protested the award. He even went so far as to write and publish a 44-page pamphlet that attempted to prove Bunche had been working as an agent of the "International Communist Conspiracy" for more than two decades.

The Alliance, Inc.

Archie additionally served as president for an organization named The Alliance, Inc., where Zygmund Dobbs was Research Director. The Alliance published books by Dobbs such as ''Red Intrigue and Race Turmoil'' (New York: The Alliance, Inc., 1958), for which Archie wrote forewords. In the foreword to ''The Great Deceit: Social Pseudo-Sciences'', Archie wrote: "Socialists have infiltrated our schools, our law courts, our government, our MEDIA OF COMMUNICATIONS.... the Socialist movement is made up of a relatively small number of people who have developed the TECHNIQUE OF INFLUENCING large masses of people to a VERY HIGH DEGREE." Johnson's book, ''Color, Communism, and Common Sense'', was quoted by G. Edward Griffin in his 1969 motion picture lecture ''More Deadly than War ... the Communist Revolution in America''. In 1958, as president of The Alliance, Inc., Roosevelt wrote the preface forManning Johnson Manning Rudolph Johnson (December 17, 1908 – July 2, 1959)

was a Communist Party USA African-American leader and the party's candidate for U.S. Representative from New York's 22nd congressional district during a special election in 1935. Later, ...

's semi-memoir, semi-polemical tract ''Color, Communism, and Common Sense''.

Personal life

Archie married Grace Lockwood, daughter of Thomas Lockwood and Emmeline Stackpole, at the Emmanuel Church inBoston, Massachusetts

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, on April 14, 1917. The couple spent most of their married life in a pre-Revolutionary house on Turkey Lane in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, not far from Oyster Bay, where they had four children:

* Archibald Bulloch Roosevelt Jr. (1918–1990), who married Katharine W. Tweed, daughter of Harrison Tweed, and later Selwa "Lucky" Showker Roosevelt (b. 1929)

* Theodora Roosevelt (1919–2008), who became a dancer and novelist under the name Theodora Keogh

* Nancy Dabney Roosevelt (1923–2010)

* Edith Kermit Roosevelt (1927–2003), a Barnard College

Barnard College is a Private college, private Women's colleges in the United States, women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college affiliated with Columbia University in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a grou ...

graduate, married 1948–1952 to Alexander Gregory Barmine; parents of Margot Roosevelt

In 1971, Archie's wife, Grace Lockwood Roosevelt, died in an automobile crash near her home on Turkey Lane in Cold Spring Harbor, with her husband at the wheel.

On October 13, 1979, Roosevelt died of a stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

at the Stuart Convalescent Home in Stuart, Florida

Stuart is a city in and the county seat of Martin County, Florida, United States. Located in southeastern Florida, Stuart is the largest of five Municipal corporation, incorporated municipalities in Martin County. The population is 17,425 accordi ...

. He was 85 years old, the last child of Theodore and Edith to die (although his half-sister Alice would outlive him by four months). He is buried with his wife at Youngs Memorial Cemetery

Youngs Memorial Cemetery is a small cemetery in the village of Oyster Bay Cove, New York in the United States of America. It is located approximately one and a half miles south of Sagamore Hill National Historic Site. The cemetery was chartered ...

, Oyster Bay. His tombstone reads: "The old fighting man home from the wars."

Descendants

Roosevelt's grandson is Tweed Roosevelt (b. 1942), who is the chairman of Roosevelt China Investments, and is the President of the Board of Trustees of the Theodore Roosevelt Association.Publications

* Roosevelt, Theodore. ''Theodore Roosevelt on Race, Riots, Reds, Crime.'' Compiled by Archibald B. Roosevelt. West Sayville,New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

: Probe Publishers, 1968.

* Zygmund, Dobbs. Red Intrigue and Race Turmoil

'' Foreword by Archibald B. Roosevelt.

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

: The Alliance, Inc., 1954.

*Zygmund, Dobbs. The Great Deceit: Social Pseudo-Sciences

'' Foreword by Archibald B. Roosevelt. Sayville, NY: Veritas Publishing, 1964.

See also

References

External links

*Quentin and his brother Archie and their father Theodore Roosevelt on film during World War I

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20070304071033/http://www.roosevelt-cross.com/home/index.php Roosevelt & Cross

U.S. Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific – Operation Cartwheel, The Reduction of Rabaul, New Guinea, US Army War College

{{DEFAULTSORT:Roosevelt, Archibald 1894 births 1979 deaths Military personnel from Washington, D.C. American people of Dutch descent United States Army personnel of World War I United States Army personnel of World War II American people of Scotch-Irish descent American people of Scottish descent Bulloch family Harvard University alumni Archibald Bulloch Roosevelt Schuyler family United States Army colonels Recipients of the Silver Star American recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) American segregationists John Birch Society members American conspiracy theorists Sidwell Friends School alumni Ritchie Boys Children of Theodore Roosevelt