Archibald Baxter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Archibald McColl Learmond Baxter (13 December 1881 – 10 August 1970) was a

In 1917 the Minister of Defence, Sir James Allen, decided that all men claiming to be conscientious objectors but not accepted as such should be sent to the Western Front. Accordingly, orders were given by Colonel H R Potter, Trentham Camp Commandant, that he along with 13 other conscientious objectors – his two brothers, William Little (Hikurangi), Frederick Adin (Foxton), Garth Carsley Ballantyne (Wellington),

In 1917 the Minister of Defence, Sir James Allen, decided that all men claiming to be conscientious objectors but not accepted as such should be sent to the Western Front. Accordingly, orders were given by Colonel H R Potter, Trentham Camp Commandant, that he along with 13 other conscientious objectors – his two brothers, William Little (Hikurangi), Frederick Adin (Foxton), Garth Carsley Ballantyne (Wellington),

Otago Daily Times, 21 January 2021, retrieved 1 July 20121 More than $100,000 were raised through grants and donations for what will be the first memorial to honour pacifism in New Zealand. The Trust hoped to unveil the memorial on the centenary of the

The Archibald Baxter Trust in Dunedin New Zealand

''Military Personnel File online''

digitised record at Archives New Zealand.

Short autobiographical account published in 1919

Book-length autobiographical account published in 1939

Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

''Field Punishment No. 1''

– 2014 TV Drama featuring the story of Archibald Baxter. * Milne, J.,

Our clever, irreverent and courageous soldiers returned from war and wanted to forget – but we will remember

" ''

New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

and conscientious objector

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for the military–indu ...

.

Early life

Baxter was born at Saddle Hill,Otago

Otago (, ; ) is a regions of New Zealand, region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island and administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local go ...

, on 13 December 1881, to John Baxter and Mary McColl. His father had migrated to New Zealand from Scotland in 1861. Leaving school at 12, Baxter worked on a farm and became Head Ploughman at Gladbrook Station.

During the 1899–1902 Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

New Zealand sent troops to help the British. Baxter considered enlisting, but heard a Dunedin lawyer, possibly Alfred Richard Barclay

Alfred Richard Barclay (8 August 1859 – 10 November 1912) was a New Zealand Member of Parliament for two Dunedin electorates, representing the Liberal Party.

Early life

Barclay was born in Ireland in 1859. He was the eldest son of the Rev. Ge ...

, speak about pacifism before he did so and decided against enlisting. He read pacifist and anti-military literature, forming a Christian Socialist

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words ''Christ'' and ''Chr ...

view. Baxter also heard Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, and was its first Leader of the Labour Party (UK), parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908. ...

speak during his 1908 visit to New Zealand and concluded that war would not solve problems. He convinced six of his seven brothers that war was wrong.

World War I

Conscription

With the introduction ofconscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

under the Military Service Act 1916

The Military Service Act 1916 (5 & 6 Geo. 5. c. 104) was an Act of Parliament, act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom during the First World War to impose conscription in Great Britain, but not in Ireland or any other British jurisdi ...

, Baxter and his brothers refused to register on the grounds that ''all war is wrong, futile, and destructive alike to victor and vanquished.''The Act did not recognise their stand, as the only grounds for a man to claim

conscientious objection

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for the military–indu ...

were:

''That he was on the fourth day of August, nineteen hundred and fourteen, and has since continuously been a member of a religious body the tenets and doctrines of which religious body declare the bearing of arms and the performance of any combatant service to be contrary to Divine revelation, and also that according to his own conscientious religious belief the bearing of arms and the performance of any combatant service is unlawful by reason of being contrary to Divine revelation.''This was a considerable contraction of the exemption allowed under the

Defence Amendment Act 1912

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense indust ...

, which had provided under Section 65(2)

''On the application of any person a Magistrate may grant to the applicant a certificate of exemption from military training and service if the Magistrate is satisfied that the applicant objects in good faith to such training and service on the ground that it is contrary to his religious belief.''The 1916 Act meant that only

Christadelphian

The Christadelphians () are a restorationist and nontrinitarian (Biblical Unitarian) Christian denomination. The name means 'brothers and sisters in Christ',"The Christadelphians, or brethren in Christ ... The very name 'Christadelphian' was co ...

s, Seventh-day Adventist

The Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA) is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbat ...

s, and Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

were to be recognised as conscientious objectors. As Baxter was not a member of one of these, he could not apply for objector status. According to the Act, Baxter was automatically deemed to be a First Division Reservist. The Act also required all eligible males to enroll in the Expeditionary Force Reserve or face up to 3 months imprisonment or a fine of £50. Baxter had not enrolled. Failing to enroll and being convicted of it also meant that Baxter could be immediately called up for service. Failure to report for duty became either desertion or absence without leave, offences under the Army Act.

Baxter and two of his brothers – Alexander and John – were arrested by civilian police in mid March 1917 for failing to enroll under the Act and were first imprisoned in The Terrace Gaol, Wellington. They were subsequently transferred directly to Trentham Military Camp

Trentham Military Camp is a New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) facility located in Trentham, Upper Hutt, near Wellington. Originally a New Zealand Army installation, it is now run by Defence and accommodates all three services. It also hosts Joint ...

when their appeals as conscientious objectors were rejected. On 21 March Archibald and John Baxter and William Little, another objector, refused to put on Army uniform; Alexander Baxter refused to work. All were Court Martialed, all stating that they did not consider themselves soldiers, having never volunteered or taken the oath of allegiance. None was represented by legal counsel. The four were sentenced to 84 days imprisonment with hard labour, served at both the Terrace Gaol and Mount Cook Prison. At the end of their sentence they were to be sent back to Trentham Camp. Back at Trentham after release, Archibald Baxter continued to refuse orders and was sentenced to 28 days detention.

Deportation to the front

In 1917 the Minister of Defence, Sir James Allen, decided that all men claiming to be conscientious objectors but not accepted as such should be sent to the Western Front. Accordingly, orders were given by Colonel H R Potter, Trentham Camp Commandant, that he along with 13 other conscientious objectors – his two brothers, William Little (Hikurangi), Frederick Adin (Foxton), Garth Carsley Ballantyne (Wellington),

In 1917 the Minister of Defence, Sir James Allen, decided that all men claiming to be conscientious objectors but not accepted as such should be sent to the Western Front. Accordingly, orders were given by Colonel H R Potter, Trentham Camp Commandant, that he along with 13 other conscientious objectors – his two brothers, William Little (Hikurangi), Frederick Adin (Foxton), Garth Carsley Ballantyne (Wellington), Mark Briggs (politician)

Mark Briggs (6 April 1884 – 15 March 1965) was a New Zealand labourer, auctioneer, pacifist, socialist and politician. He was born in Londesborough, Yorkshire, England, on 6 April 1884.

In World War I, he was one of the group of 14 New Zealand ...

, David Robert Gray (Hinds. Canterbury), Thomas Percy Harland (Roslyn, Dunedin), Lawrence Joseph Kirwan (Hokitika), Daniel Maguire (Foxton), Lewis Edward Penwright (Geeverton, Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

), Henry Patton (Cobden Greymouth) and Albert Ernest Sanderson (Babylori, North Wairoa) – were to be shipped out. On 24 July they were embarked on the troopship '' Waitemata'' en voyage to Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, where a measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

epidemic on board caused the ship to stop. Archibald, Jack and Sanderson and some troops were taken to hospital, and the ship was condemned by the port authorities as unfit for troops, necessitating the civilian liner ''Norman Castle'' being used to take the main military group, including the other COs, to England.

After recovery, Archibald and the other two COs were taken on the civilian liner ''Llanstephan Castle'', arriving at Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

, Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

, on 26 December. Baxter was still refusing to put on a uniform or do any work for the army. He was kept under detention at Sling Camp

Sling Camp was a World War I camp occupied by New Zealand soldiers beside the then-military town of Bulford on the Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England.

History

The camp was initially created as an annexe to Bulford Camp in 1903; it was originall ...

, Salisbury Plain

Salisbury Plain is a chalk plateau in southern England covering . It is part of a system of chalk downlands throughout eastern and southern England formed by the rocks of the Chalk Group and largely lies within the county of Wiltshire, but st ...

, and then sent to France, Folkestone

Folkestone ( ) is a coastal town on the English Channel, in Kent, south-east England. The town lies on the southern edge of the North Downs at a valley between two cliffs. It was an important harbour, shipping port, and fashionable coastal res ...

–Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

, and on to Étaples

Étaples or Étaples-sur-Mer (; or ; formerly ; ) is a communes of France, commune in the departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais, Hauts-de-France, northern France. It is a fishing and leisure port on the Canche river.

History

Étapl ...

. British newspapers of the time reported that because he had been sent to the front he could be shot for disobeying orders.

There Baxter remained under detention and continued to refuse any military involvement. He had been assigned to E Company of the 28th Reinforcements, led by Captain Frederick Harold Batten, father of the aviator Jean Batten

Jane Gardner Batten (15 September 1909 – 22 November 1982), commonly known as Jean Batten, was a New Zealand Aircraft pilot, aviator who made several record-breaking flights – including the first solo flight from England to New Zealand i ...

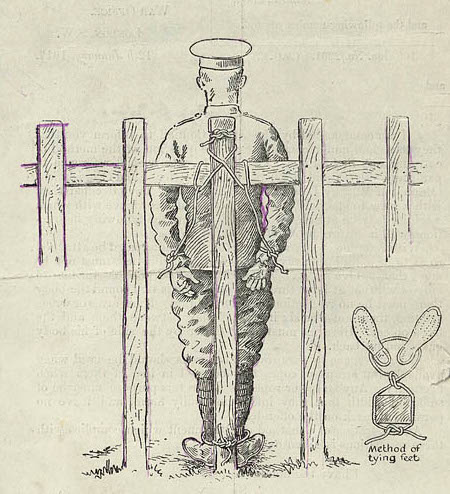

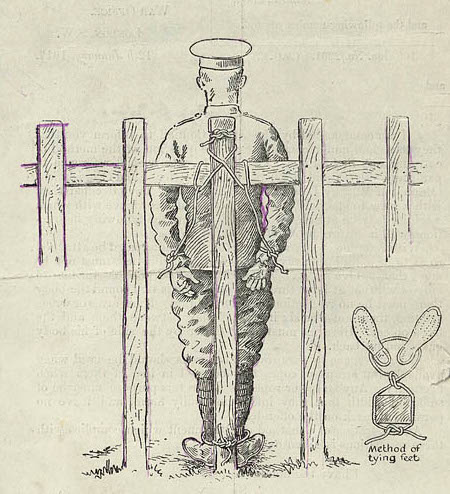

. He was placed under Lt Col George Mitchell, 3rd Otago Reserve Battalion, who investigated his case, questioning him about his beliefs, but ultimately finding that he was considered a soldier by the New Zealand Government. Mitchell told Baxter that if he did not obey military orders he should expect to be punished, as determined by Mitchell. Eventually Mitchell punished Baxter with 28 days of Field Punishment No.1 at Ouderdom (near Ypres in Belgium).

A doctor examined Baxter before the punishment, and despite telling Baxter he thought he was unfit for it, spitefully passed him as fit. Because the personnel at Ouderdom would not punish him, he was moved to ''Mud Farm'' near Dickebusch (also known as Dikkebus) in West Flanders

West Flanders is the westernmost province of the Flemish Region, in Belgium. It is the only coastal Belgian province, facing the North Sea to the northwest. It has land borders with the Dutch province of Zeeland to the northeast, the Flemis ...

, where he was put under two hours punishment each day. Eventually he was sent to Abeele

Abele (also spelled Abeele) is a small village or hamlet in the city of Poperinge, in the Belgian province of West Flanders. The village is located on the territory of Poperinge proper and its "deelgemeente" Watou, but is also partly located on ...

and back to Mitchell. On 5 March Mitchell ordered him up to the lines at Ypres

Ypres ( ; ; ; ; ) is a Belgian city and municipality in the province of West Flanders. Though

the Dutch name is the official one, the city's French name is most commonly used in English. The municipality comprises the city of Ypres/Ieper ...

. Provost Sergeant Booth was put in charge of Baxter and at one time punched him in the face and beat him up, Booth saying he had been ordered to do so. Baxter was placed under Captain Phillips and taken to the Otago Infantry Regiment

The Otago Infantry Regiment (Otago Regiment) was a military unit that served within the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) in World War I during the Gallipoli Campaign (1915) and on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front (1916–191 ...

camp. He was then returned to Booth's supervision.

At one stage Booth, on direction from a Captain Stevenson, placed Baxter by an ammunition dump being shelled by the Germans. Despite a heavy barrage, Baxter was unharmed. After further abusive treatment including starvation, he suffered a complete physical and mental breakdown, and was sent to hospital in England about May 1918. According to his records, by the time he went to hospital he had been assigned to the 3rd New Zealand Entrenching Battalion

Entrenching battalions were temporary units formed in the armies of the British Empire during the First World War. Entrenching Battalions were trained as infantry, but were primarily utilized for manual labour duties such as trench repair, wire l ...

.

Baxter was said to have been diagnosed as suffering from melancholia

Melancholia or melancholy (from ',Burton, Bk. I, p. 147 meaning black bile) is a concept found throughout ancient, medieval, and premodern medicine in Europe that describes a condition characterized by markedly depressed mood, bodily complain ...

. He was returned to New Zealand, but during the voyage was diagnosed as being in good mental and physical health. He arrived on 21 September 1918, and returned to his Otago

Otago (, ; ) is a regions of New Zealand, region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island and administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local go ...

farm after the war.

The physical treatment given to Baxter can to a large extent be directly attributed to the attitudes of the Minister of Defence, Allen; the Commander of New Zealand forces based in England, Brigadiar-General Sir George Richardson, and General Godley, Commander of the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces. Godley gave orders that if Baxter and the others failed to comply, they were to be "summarily punished or dealt with at reinforcement camps, where they are now, and that they are not to be sent up to the front." Neither Allen nor Richardson had any such qualms and were likely to be the reason behind Baxter being taken to the front.

Reaction in New Zealand and England

Concern about the fate of Baxter and the others sent to France began to be raised by the Dunedin branch of the Women's International League. The Canterbury Women's Institute also wrote expressing concern. In late 1917 English Quaker and wife of the late John Ellis, Maria Rountree, wrote about trying to find the fate of the 14 objectors, only to be stonewalled by the Commander of the New Zealand forces, Richardson.Harry Holland

Henry Edmund Holland (10 June 1868 – 8 October 1933) was an Australian-born newspaper owner, politician and unionist who relocated to New Zealand. He was the second leader of the New Zealand Labour Party.

Early life

Holland was born at G ...

MP, citing an article in the ''Dominion'' on 21 November, deduced that the British Government had condemned the New Zealand government's sending of conscientious objectors to the front. The paper had written, "the Imperial authorities have no wish to be troubled with men who will not fight,..". This effectively ended such deportations, but did not mean the release of those already in France.

In February 1918 the National Peace Council of New Zealand, wrote to the Minister of Defence, James Allen, expressing concern about the treatment of Baxter and the others. Of particular concern was the sending of the objectors to the front, where they could be court-martialled and shot for not fighting the enemy. Harry Holland MP also took up their cases, writing to the Prime Minister and newspapers.

As further news came of the inhumane way Baxter had been treated by the military, it was the subject of a Women's International League delegation to the Acting Prime Minister and Minister of Defence, Sir James Allen in June 1918. The treatment of both him and the other objectors continued to be raised after the war by Harry Holland MP and others. In 2014 a docu-drama of his treatment entitled ''Field Punishment No 1'' was televised.

The attitude of the military of the day towards Baxter was summed up in a letter from Colonel Robert Tate, Adjutant-General, New Zealand Military Headquarters, in which he stated ''Regarding Archibald Baxter ... the sympathy of many earnest people who would like to see the lot of the conscientious objector alleviated, is wasted on men axterwho are in no sense conscientious but are merely defiant of all control and willing to be subject to no law but their own inclinations. ...''

Inter-war period

On 12 February 1921 Archibald married Millicent Amiel Macmillan Brown, daughter of the lateHelen Connon

Helen Connon ( 1860 – 22 February 1903) was an educational pioneer from Christchurch, New Zealand. She was the first woman in the British Empire to receive a university degree with honours.

Early life

Connon was born in Melbourne, in 1859 o ...

, and Professor John Macmillan Brown, founding chair of Canterbury College. Brown opposed the marriage due to the disparity in the couple's backgrounds – Millicent, educated overseas, and Archie, who had received only a primary education. Millicent, in her autobiography, stated that she had heard of Baxter in 1918 and became a pacifist a short time later.

During the 1920s the Baxters farmed at Brighton and had two sons, Terence (born 1922) and James Keir

James Keir FRS (20 September 1735 – 11 October 1820) was a Scottish chemist, geologist, industrialist, and inventor, and an important member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham.

Life and work

Keir was born in Stirlingshire, Scotland, in 1 ...

(born 1926). James' middle name was chosen in honour of Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, and was its first Leader of the Labour Party (UK), parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908. ...

, a founder of the Labour Party in Britain, who notably spoke against war at a rally in London on 2 August 1914, two days before Britain (and New Zealand) declared war. James grew up to become one of New Zealand's most famous poets, and both sons became pacifists.

With Millicent's support, he founded the Dunedin Branch of the New Zealand No More War Movement The No More War Movement was the name of two pacifist organisations, one in the United Kingdom

and one in New Zealand.

British group

The British No More War Movement (NMWM) was founded in 1921 as a pacifist and socialist successor to the No-Consc ...

in 1931. The movement sought to end conscription and promote disarmament. His father-in-law died in the 1930s and the Baxters inherited enough from his estate to enable them to travel. They moved to Wanganui

Whanganui, also spelt Wanganui, is a list of cities in New Zealand, city in the Manawatū-Whanganui region of New Zealand. The city is located on the west coast of the North Island at the mouth of the Whanganui River, New Zealand's longest nav ...

, then went to Salisbury

Salisbury ( , ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers River Avon, Hampshire, Avon, River Nadder, Nadder and River Bourne, Wi ...

, England in 1937. Baxter addressed the 5th War Resisters' International

War Resisters' International (WRI), headquartered in London, is an international anti-war organisation with members and affiliates in over 40 countries.

History

''War Resisters' International'' was founded in Bilthoven, Netherlands in 1921 un ...

conference (the last before World War II) in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

, 23–26 July. While living at Salisbury he wrote his account of his World War I experiences, published as ''We Will Not Cease'' in 1939. The family returned to New Zealand in 1938.

World War II

Both of Baxter's sons followed their parents' pacifism. His elder son, Terence, was imprisoned for refusing conscription during World War II. The National Service Emergency Regulations 1940, under which he was called up, were almost as limiting on the grounds for conscientious objection as the 1916 Act. Regulation 21 (2) required the person objecting to prove they held ".. a genuine belief that it is wrong to engage in warfare in any circumstances." The regulation further stated that "Evidence of active and genuine membership of a pacifist religious body may in general be accepted as evidence of the convictions of the objector..." Active and continuous membership of the Society of Friends or Christadelphians prior to the outbreak of war was taken sufficient proof. The Appeal Boards set up under the regulations tended to take a very narrow and sometimes contradictory view of conscientious objectors. After an April 1941 British court case those deemed to be politically based were unlikely to be accepted. The continuation of conscription must have been ironic for Baxter as many members of the now governing Labour Party had been imprisoned during World War I for opposing conscription. The prime minister,Michael Joseph Savage

Michael Joseph Savage (23 March 1872 – 27 March 1940) was an Australian-born New Zealand politician who served as the 23rd prime minister of New Zealand, heading the First Labour Government of New Zealand, First Labour Government from 1935 ...

, had been very vocal opposing conscription during that war.

During the war Baxter was an active member of the Dunedin Branch of the New Zealand Peace Pledge Union

The Peace Pledge Union (PPU) is a non-governmental organisation that promotes pacifism, based in the United Kingdom. Its members are signatories to the following pledge: "War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determine ...

.

Later years

After the war the Baxters continued their involvement with thepeace movement

A peace movement is a social movement which seeks to achieve ideals such as the ending of a particular war (or wars) or minimizing inter-human violence in a particular place or situation. They are often linked to the goal of achieving world pe ...

. They lobbied against nuclear weapons, supported Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says that it has more than ten million members a ...

, and wrote against the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, about which in 1968 Archibald said: ''…the only apparent justification that war ever had was that by destroying some lives it might clumsily preserve others. But now even that justification is being stripped away. We make war chiefly on civilians and respect for human life seems to have become a thing of the past. To accept this situation would be to accept the Devil's philosophy.''During the 1950s–60s the Baxters also took a keen interest in botany, discovering on a trip to

Dunstan

Dunstan ( – 19 May 988), was an English bishop and Benedictine monk. He was successively Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, Bishop of Worcester, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury, later canonised. His work restored monastic life in En ...

a new plant species now known as ''Gingidia baxterae''.

In 1965, Baxter's younger son James convinced both Archibald and Millicent to become Roman Catholics.

Baxter lived in Dunedin until his death on 10 August 1970.

Archibald Baxter Memorial Trust

In 2013 a group in Dunedin, chaired by Kevin P. Clements of theUniversity of Otago

The University of Otago () is a public university, public research university, research collegiate university based in Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand. Founded in 1869, Otago is New Zealand's oldest university and one of the oldest universities in ...

National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, set up the Archibald Baxter Memorial Trust to honour Baxter and other conscientious objectors of the First World War. Ian Fraser is the trust's patron, and trustees include Baxter's granddaughter Katherine Baxter.

The Trust proposed an annual lecture in Baxter's name, an annual essay competition commencing in August 2014, and a memorial in Dunedin in Baxter's honour."Pacifists Deserve Recognition", ''Otago Daily Times'', 30 December 2013 The first lecture was given on 22 September 2014 by Australian historian and author Professor Henry Reynolds of the University of Tasmania

The University of Tasmania (UTAS) is a public research university, primarily located in Tasmania, Australia. Founded in 1890, it is Australia's fourth oldest university. Christ College (University of Tasmania), Christ College, one of the unive ...

. His lecture was titled ''Discovering Archibald Baxter and the thoughts on war which followed''. The topic for the Trust's first essay competition was ''They also served who would not fight'' and was to be set against a backdrop of New Zealand History. There were two age group categories: Junior (New Zealand school years 9–11) and Senior (New Zealand school years 12–13). The senior section was won by Modi Deng of Columba College

Columba College is an integrated Presbyterian school in Roslyn, Otago, Roslyn, Dunedin, New Zealand. The roll is made up of pupils of all ages. The majority of pupils are in the girls' secondary, day and boarding school, but there is also a p ...

and the Junior section by Rhys Davie of Tokomairiro High School

Tokomairiro High School is a co-educational, state secondary school in Milton, New Zealand, Milton, New Zealand, often simply known as "Toko".

History

Founded in 1856 as Tokomairiro School, it is one of New Zealand's oldest schools. It was orig ...

.Work Start on Baxter MemorialOtago Daily Times, 21 January 2021, retrieved 1 July 20121 More than $100,000 were raised through grants and donations for what will be the first memorial to honour pacifism in New Zealand. The Trust hoped to unveil the memorial on the centenary of the

Battle of Passchendaele

The Third Battle of Ypres (; ; ), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele ( ), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by the Allies of World War I, Allies against the German Empire. The battle took place on the Western Front (World Wa ...

in 2017, however resource consent

A resource consent is the authorisation given to certain activities or uses of natural and physical resources required under the New Zealand Resource Management Act (the "RMA"). Some activities may either be specifically authorised by the RMA or ...

was not granted until July 2018. Construction of the memorial, which is estimated to cost $300,000, commenced in April 2021 at a site on the corner of George and Albany Streets, Dunedin and was officially opened on 29 October 2021.

Literature and film

* ''Field Punishment Number One'', David Grant, paintings byBob Kerr Robert Kerr may refer to:

Sportsmen

* Robert Kerr (Australian footballer) (born 1967), former Australian rules footballer

* Robert Kerr (athlete) (1882–1963), Canadian athlete & Olympic medalist

* Robbie Kerr (racing driver) (born 1979), English ...

, Steel Roberts publishers, Wellington, 2008, page 106,

* ''My Brother's War'', David Hill, Penguin, 2012 – the story in this book draws from Baxter's experiences.

* ''Field Punishment No 1'', (2014) – docu-drama based on David Grant's book

See also

*Christian pacifism

Christian pacifism is the Christian theology, theological and Christian ethics, ethical position according to which pacifism and non-violence have both a scriptural and rational basis for Christians, and affirms that any form of violence is inco ...

* Compulsory Military Training in New Zealand

* List of peace activists

This list of peace activists includes people who have proactively advocated Diplomacy, diplomatic, philosophical, and non-military resolution of major territorial or ideological disputes through nonviolent means and methods. Peace activists usua ...

References

Bibliography

* Baker, Paul. ''King and Country Call: New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War''. Auckland, New Zealand,Auckland University Press

Auckland University Press is a New Zealand publisher that produces creative and scholarly work for a general audience. Founded in 1966 and formally recognised as Auckland University Press in 1972, it is a publisher based within the University ...

, 1988,

* Baxter, M. ''The Memoirs of Millicent Baxter''. Whatamongo Bay, Cape Catley Ltd., 1981,

* McKay, F. ''The Life of James K. Baxter''. Auckland, Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 1990,

External links

The Archibald Baxter Trust in Dunedin New Zealand

''Military Personnel File online''

digitised record at Archives New Zealand.

Short autobiographical account published in 1919

Book-length autobiographical account published in 1939

Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

''Field Punishment No. 1''

– 2014 TV Drama featuring the story of Archibald Baxter. * Milne, J.,

Our clever, irreverent and courageous soldiers returned from war and wanted to forget – but we will remember

" ''

stuff.co.nz

Stuff is a New Zealand news media website owned by newspaper conglomerate Stuff Ltd (formerly called Fairfax). As of early 2024, it is the most popular news website in New Zealand, with a monthly unique audience of more than 2 million.

Stuff ...

'', 10 November 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Baxter, Archibald

1881 births

1970 deaths

19th-century New Zealand people

Anglican pacifists

Anti–Vietnam War activists

New Zealand anti-war activists

New Zealand anti–World War I activists

New Zealand Army personnel

New Zealand autobiographers

New Zealand Christian pacifists

New Zealand conscientious objectors

New Zealand pacifists

New Zealand people of Scottish descent

New Zealand people of World War I

New Zealand socialists

New Zealand torture victims

People from Otago