Anti-miscegenation Law on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-miscegenation laws are laws that enforce

"Hollywood Loved Sammy Davis Jr. Until He Dated a White Movie Star"

'' Smithsonian'' Retrieved February 23, 2021. In 1958, officers in

An anti-miscegenation law was enacted by the

An anti-miscegenation law was enacted by the

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalizing interracial marriage

Interracial marriage is a marriage involving spouses who belong to different "Race (classification of human beings), races" or Ethnic group#Ethnicity and race, racialized ethnicities.

In the past, such marriages were outlawed in the United Sta ...

sometimes, also criminalizing sex between members of different races.

In the United States, interracial marriage, cohabitation and sex have been termed "miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is marriage or admixture between people who are members of different races or ethnicities. It has occurred many times throughout history, in many places. It has occasionally been controversial or illegal. Adjectives describin ...

" since the term was coined in 1863. Contemporary usage of the term is infrequent, except in reference to historical laws which banned the practice. Anti-miscegenation laws were first introduced in North America by the governments of several of the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

from the late seventeenth century onward, and subsequently, they were introduced by the governments of many U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

s and U.S. territories

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indian reservations in th ...

and they remained in force in many US states until 1967. After the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, an increasing number of states repealed their anti-miscegenation laws. In 1967, in the landmark case ''Loving v. Virginia

''Loving v. Virginia'', 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that ruled that the laws banning interracial marriage violate the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to ...

'', the remaining anti-miscegenation laws were ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

under Chief Justice Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 30th governor of California from 1943 to 1953 and as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presid ...

.

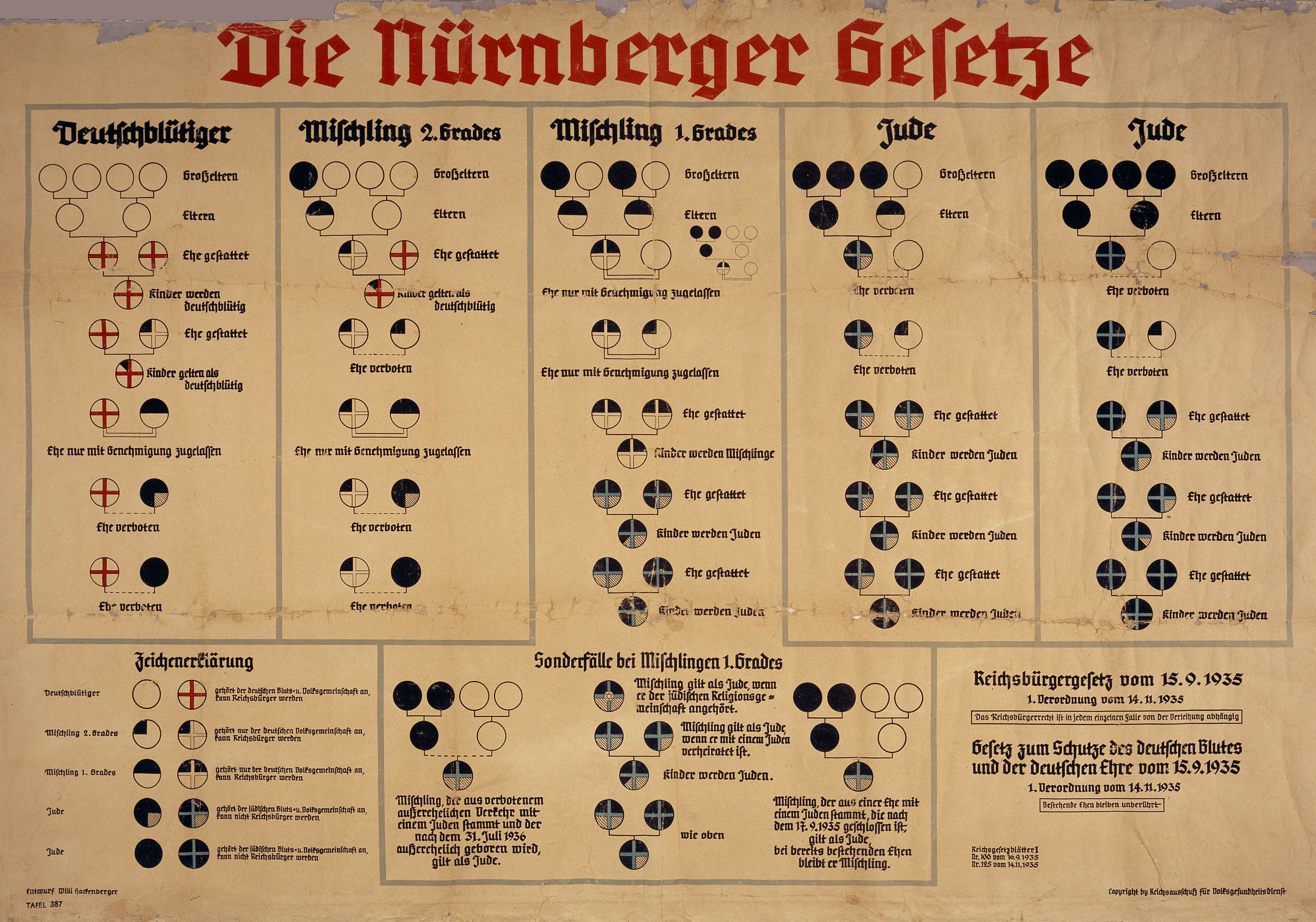

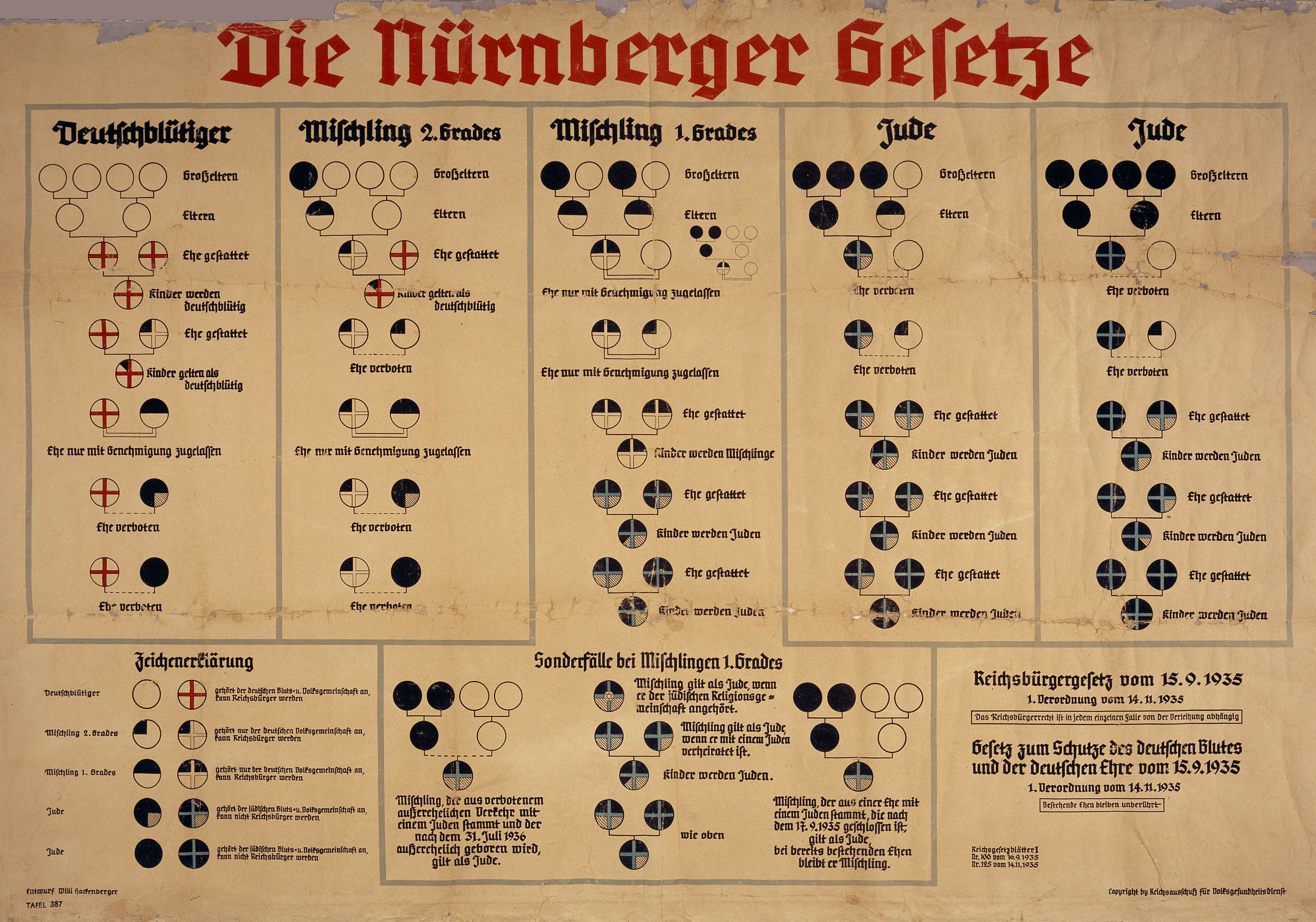

Anti-miscegenation laws were also enforced in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

as a part of the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of the Nazi Party. The two laws were the Law ...

which were passed in 1935, and they were also enforced in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

as a part of the system of apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

which was introduced in 1948.

United States

The first ever anti-miscegenation law was passed by theMaryland General Assembly

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland that convenes within the State House in Annapolis. It is a bicameral body: the upper chamber, the Maryland Senate, has 47 representatives, and the lower ...

in 1691, criminalizing interracial marriage. In a speech in Charleston, Illinois

Charleston is a city in and the county seat of Coles County, Illinois, United States. The population was 17,286, as of the 2020 census. The city is home to Eastern Illinois University and has close ties with its neighbor, Mattoon, Illinois, Ma ...

, in 1858, Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

stated, "I am not, nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people". By the late 1800s, 38 U.S. states had anti-miscegenation statutes. By 1924, the ban on interracial marriage was still in force in 29 states. While interracial marriage had been legal in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

since 1948, in 1957 actor Sammy Davis Jr.

Samuel George Davis Jr. (December 8, 1925 – May 16, 1990) was an American singer, actor, comedian, dancer, and musician.

At age two, Davis began his career in Vaudeville with his father Sammy Davis Sr. and the Will Mastin Trio, which t ...

faced backlash for his relationship with a white woman, actress Kim Novak

Marilyn Pauline "Kim" Novak (born February 13, 1933) is an American retired actress and painter. Her contributions to cinema have been honored with two Golden Globe Awards, an Honorary Golden Bear, a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, and a s ...

. In 1958, Davis briefly married a black woman, actress and dancer Loray White, to protect himself from mob violence.Lanzendorfer, Joy (August 9, 2017"Hollywood Loved Sammy Davis Jr. Until He Dated a White Movie Star"

'' Smithsonian'' Retrieved February 23, 2021. In 1958, officers in

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

entered the home of Richard and Mildred Loving and dragged them out of bed for living together as an interracial couple, on the basis that "any white person intermarry with a colored person"— or vice versa—each party "shall be guilty of a felony" and face prison terms of five years. When former president Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

was asked by a reporter in 1963 if interracial marriage would become widespread in the U.S., he responded, "I hope not; I don’t believe in it", before adding "Would you want your daughter to marry a Negro? She won't love someone who isn't her color." In 1967 the law banning interracial marriage was ruled unconstitutional (via the 14th Amendment adopted in 1868) by the U.S. Supreme Court in ''Loving v. Virginia

''Loving v. Virginia'', 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that ruled that the laws banning interracial marriage violate the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to ...

''. Many states refused to adapt their laws to this ruling with Alabama in 2000 being the last US state to remove anti-miscegenation language from the state constitution. Even with many states having repealed the laws and with the state laws becoming unenforceable, in the United States in 1980 only 2% of marriages were interracial.

South Africa

Early prohibitions on interracial marriages date back to the rule of theDutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

when High Commissioner Van Rheede prohibited marriages between European settlers and ''heelslag'' or full-blooded slave women (that is, of pure Asian or African origin) in 1685. The ban was never enforced.

In 1905, German South West Africa banned the "Rassenmischehe" (racial mixed marriage). These bans had no legal basis in German citizenship laws (issued in 1870 and 1913) and the "decrees ere

Ere or ERE may refer to:

* ''Environmental and Resource Economics'', a peer-reviewed academic journal

* ERE Informatique, one of the first French video game companies

* Ere language, an Austronesian language

* Ebi Ere (born 1981), American-Nigeria ...

issued by either a colonial governor or the colonial secretary", they were "not laws that had received the approval of the Reichstag". Similar such laws were also adopted in the German colonies of German East Africa (1906) and German Samoa (1912).

In 1927, the Pact coalition government passed a law prohibiting marriages between whites and blacks (though not between whites and "coloured" people). An attempt was made to extend this ban in 1936 to marriages between whites and coloureds when a bill was introduced in parliament, but a commission of inquiry recommended against it.

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

's Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act

The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, Act No. 55 of 1949, was an apartheid-era law in South Africa that prohibited marriages between "whites" and "non-whites". It was among the first pieces of apartheid legislation to be passed following the Na ...

, passed in 1949 under apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

, forbade marriages between whites and anyone who was deemed to be non-whites. The Population Registration Act

The Population Registration Act of 1950 required that each inhabitant of South Africa be classified and registered in accordance with their racial characteristics as part of the system of apartheid.

Social rights, political rights, educational ...

(No. 30) of 1950 provided the basis for separating the population of South Africa into different races. Under the terms of this act, all residents of South Africa were to be classified as either a native "white" South African, a "black" immigrant (these typically originating from Bantu lands across the border to the north), or a "colored" person of visibly mixed race parentage. Indians were included under the category "Asian" in 1959. Also in 1950, the Immorality Act

Immorality Act was the title of two acts of the Parliament of South Africa which prohibited, amongst other things, sexual relations between white people and people of other races. The first Immorality Act, of 1927, prohibited sex outside of marri ...

was passed, which criminalized all sexual relations

Human sexual activity, human sexual practice or human sexual behaviour is the manner in which humans experience and express their sexuality. People engage in a variety of sexual acts, ranging from activities done alone (e.g., masturbation) t ...

between whites and non-whites. The Immorality Act of 1950 extended an earlier ban on sexual relations between whites and blacks (the Immorality Act o. 5of 1927) to a ban on sexual relations between whites and any non-whites. Both Acts were repealed in 1985 as a part of the reforms which were carried out during the tenure of P. W. Botha

Pieter Willem Botha, ( , ; 12 January 1916 – 31 October 2006) was a South African politician who served as the last Prime Minister of South Africa from 1978 to 1984 and as the first executive State President of South Africa from 1984 until ...

.

Australia

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, so-calledHalf-Caste Act

''Half-Caste Act'' was the common name given to Acts of Parliament passed in the colony of Victoria (''Aboriginal Protection Act 1886'') and the colony of Western Australia (''Aborigines Protection Act 1886'') in 1886. They became the model fo ...

s in the Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland regulated marriage between indigenous and non-indigenous adults, often requiring permission from an official to marry. Officials were concerned with controlling relations between indigenous women and Chinese fishermen and pearl divers. From the mid-1930s there was a shift to control who Aboriginal peoples could marry, in order to promote assimilation, until 1961 when the federal Marriage Act

Marriage Act may refer to a number of pieces of legislation:

Australia

* Marriage Act 1961, Australia's law that governs legal marriage.

* Marriage Amendment (Definition and Religious Freedoms) Act 2017

Canada

* '' Civil Marriage Act'' passed ...

removed all restrictions.

Asia

China

Laws and policies which discouraged miscegenation were passed during the rule of various dynasties, including an 836 AD decree which forbade Chinese people from having relationships with members of other people groups such as Iranians, Africans, Arabs, Indians, Malays, Sumatrans, and so on.India

While there are no specific provisions regarding the freedom to marry someone who is a member of a different race in theConstitution of India

The Constitution of India is the supreme law of India, legal document of India, and the longest written national constitution in the world. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures ...

, Article 21 of the Constitution, which is a Fundamental Right

Fundamental rights are a group of rights that have been recognized by a high degree of protection from encroachment. These rights are specifically identified in a constitution, or have been found under due process of law. The United Nations' Susta ...

, is widely regarded as to provide that freedom as it comes under "personal liberty", which the Constitution guarantees to protect.

After the events of the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against Company rule in India, the rule of the East India Company, British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the The Crown, British ...

, several anti-miscegenation laws were passed by the British colonial government.

North Korea

After the deterioration of relations between North Korea and the Soviet Union in the 1960s, North Korea began to enact practices such as forcing its male citizens who had married Eastern European women todivorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganising of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the M ...

them.

Additionally, the North Korean government has been accused of performing forced abortion

Forced abortion is a form of reproductive coercion that refers to the act of compelling a woman to undergo termination of a pregnancy against her will or without explicit consent. Forced abortion may also be defined as coerced abortion, and may o ...

s and infanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose being the prevention of re ...

s on repatriated defectors

In politics, a defector is a person who gives up allegiance to one state in exchange for allegiance to another, changing sides in a way which is considered illegitimate by the first state. More broadly, defection involves abandoning a person, ca ...

to "prevent the survival of half-Chinese babies".

Europe

Nazi Germany

The U.S. was the global leader of countries where codified racism was practiced, and its race laws fascinated the Nazis. The ''National Socialist Handbook for Law and Legislation'' of 1934–1935, edited by the lawyerHans Frank

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician, lawyer and convicted war criminal who served as head of the General Government in German-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Frank was an early member ...

, contains a pivotal essay by Herbert Kier on the recommendations for race legislation which devoted a quarter of its pages to U.S. legislation—from segregation, race based citizenship, immigration regulations, and anti-miscegenation. The Nazis enacted miscegenation statutes which discriminated against Jews, Roma and Sinti ("Gypsies"), and Black people. The Nazis considered the Jews to be a race supposedly bound by close genetic (blood) ties to form a unit which one could neither join nor secede from, rather than a religious group of people. The influence of Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

s had been declared to have detrimental impact on Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, in order to justify the discrimination and persecutions of Jews. To be spared, one had to prove one's Aryan descent, normally by obtaining an Aryan certificate

In Nazi Germany, the Aryan certificate or Aryan passport () was a document which certified that a person was a member of the presumed Aryan race. Beginning in April 1933, it was required from all employees and officials in the public sector, ...

.

Jews, Romani and Black people

AlthoughNazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

doctrine stressed the importance of physiognomy and genes in determining race, in practice, race was only determined through the religions which were followed by each individual's ancestors. Individuals were considered non-'Aryan' (i.e. Jewish) if at least three of four of their grandparents had been enrolled as members of a Jewish congregation; it did not matter if those grandparents had been born to a Jewish mother or had converted to Judaism. The actual religious beliefs of the individual himself or herself were also immaterial, as was the individual's status under halakhic

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is based on biblical commandments (''mitzv ...

law.

An anti-miscegenation law was enacted by the

An anti-miscegenation law was enacted by the Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

government in September 1935 as a part of the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of the Nazi Party. The two laws were the Law ...

. The ''Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour'' ('Gesetz zum Schutze des deutschen Blutes und der deutschen Ehre'), enacted on 15 September 1935, forbade sexual relations and marriages between Germans classified as so-called 'Aryans' and Germans classified as Jews. This applied also to marriages concluded in Germany with only one spouse of German citizenship. On 26 November 1935, the law was extended to include, "Gypsies, Negroes or their bastard offspring". Such extramarital intercourse was marked as ''Rassenschande

''Rassenschande'' (, "racial shame") or ''Blutschande'' ( "blood disgrace") was an anti-miscegenation concept in Racial policy of Nazi Germany, Nazi German racial policy, pertaining to sexual relations between Aryan race#Nazism, Aryans and non-A ...

'' ("race defilement") and could be punished by imprisonment — later usually followed by the deportation to a concentration camp

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploitati ...

, often entailing the inmate's death. Germans of African and other non-European descent were classified following their own origin or the origin of their parents. Sinti and Roma ("Gypsies") were mostly categorised following police records, e.g. mentioning them or their forefathers as Gypsies, when having been met by the police as travelling peddlers.

The existing 20,454 (as of 1939) marriages between persons ''racially'' regarded as so-called 'Aryans' and non-Aryans — called ''mixed marriages'' () — would continue. However, the government eased the conditions for the divorce of mixed marriages. In the beginning the Nazi authorities hoped to make the 'Aryan' partner get a divorce from their non-Aryan-classified spouses, by granting easy legal divorce procedures and opportunities for the 'Aryan' spouse to withhold most of the common property after a divorce. Those who stuck to their spouse would suffer discriminations like dismissal from public employment, exclusion from civic society organisations, etc.

Any children — whenever born — within a mixed marriage, as well as children from extramarital mixed relationships born until 31 July 1936, were discriminated against as ''Mischling

(; ; ) was a pejorative legal term which was used in Nazi Germany to denote persons of mixed " Aryan" and "non-Aryan", such as Jewish, ancestry as they were classified by the Nuremberg racial laws of 1935. In German, the word has the general ...

e''. However, children later born to mixed parents, not yet married at passing the Nuremberg Laws, were to be discriminated against as ''Geltungsjude

Geltungsjude was the term for people who were considered Jews by the first supplementary decree to the Nuremberg Laws from 14 November 1935. The term was not used officially, but was coined because the persons were deemed (''gelten'' in German) ...

n'', regardless if the parents had meanwhile married abroad or remained unmarried. Any children who were enrolled in a Jewish congregation were also subject to discrimination as ''Geltungsjuden''.

According to the Nazi family value attitude, the husband was regarded the head of a family. Thus people living in a mixed marriage were treated differently according to the sex of the 'Aryan' spouse and according to the religious affiliation of the children, their being or not being enrolled with a Jewish congregation. Nazi-termed mixed marriages were often not interfaith marriage

Interfaith marriage, sometimes called interreligious marriage or mixed marriage, is marriage between spouses professing and being legally part of different religions. Although interfaith marriages are often established as civil marriages, in so ...

s, because in many cases the classification of one spouse as non-Aryan was only due to her or his grandparents being enrolled with a Jewish congregation or else classified as non-Aryan. In many cases both spouses had a common faith, either because the parents had already converted or because at marrying one spouse converted to the religion of the second (marital conversion

Marital conversion is religious conversion upon marriage, either as a conciliatory act, or a mandated requirement according to a particular religious belief. Endogamous religious cultures may have certain opposition to interfaith marriage and ...

). Traditionally the wife used to be the convert. However, in urban areas and after 1900, actual interfaith marriages occurred more often, with interfaith marriages legally allowed in some states of the German Confederation

The German Confederation ( ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, which had been dissolved ...

since 1847, and generally since 1875, when civil marriage

A civil marriage is a marriage performed, recorded, and recognized by a government official. Such a marriage may be performed by a religious body and recognized by the state, or it may be entirely secular.

History

Countries maintaining a popul ...

became an obligatory prerequisite for any religious marriage ceremony throughout the united Germany.

Most mixed marriages occurred with one spouse being considered as non-Aryan, due to his or her Jewish descent. Many special regulations were developed for such couples. A differentiation of privileged and other mixed marriages emerged on 28 December 1938, when Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

discretionarily ordered this in a letter to the ''Reich's Ministry of the Interior''. The "Gesetz über die Mietverhältnisse mit Juden" () of 30 April 1939, allowing proprietors to unconditionally cancel tenancy contracts with Germans classified as Jews, thus forcing them to move into houses reserved for them, for the first time enacted Göring's creation. The law defined ''privileged mixed marriages'' and exempted them from the act.

The legal definitions decreed that the marriage of a Gentile husband and his wife, being a Jewess or being classified as a Jewess due to her descent, was generally considered to be a ''privileged mixed marriage'', unless they had children who were enrolled in a Jewish congregation. Then the husband was obviously not the dominant part in the family and the wife had to wear the yellow badge

The yellow badge, also known as the yellow patch, the Jewish badge, or the yellow star (, ), was an accessory that Jews were required to wear in certain non-Jewish societies throughout history. A Jew's ethno-religious identity, which would be d ...

and the children as well, who were thus discriminated against as ''Geltungsjuden''. Without children, or with children not enrolled with a Jewish congregation, the Jewish-classified wife was spared from wearing the yellow badge (else compulsory for Germans classified as Jews as of 1 September 1941).

In the opposite case, when the wife was classified as a so-called 'Aryan' and the husband as a Jew, the husband had to wear the yellow badge, if they had no children or children enrolled with a Jewish congregation. In case they had common children not enrolled in a Jewish congregation (irreligionist, Christian etc.) they were discriminated as ''Mischlinge'' and their father was spared from wearing the yellow badge.

Since there was no elaborate regulation, the practice of exempting ''privileged mixed marriages'' from anti-Semitic invidiousnesses varied amongst Greater Germany's different Reichsgau

A (plural ) was an administrative subdivision created in a number of areas annexed by Nazi Germany between 1938 and 1945.

Overview

The term was formed from the words (realm, empire) and , the latter a deliberately medieval-sounding word wi ...

e. However, all discriminations enacted until 28 December 1938, remained valid without exemptions for ''privileged mixed marriages''. In the Reichsgau Hamburg, for example, Jewish-classified spouses living in ''privileged mixed marriages'' received equal food rations like Aryan-classified Germans. In many other Reichsgaue they received shortened rations.Beate Meyer, ''Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der Hamburger Juden 1933–1945'', Landeszentrale für politische Bildung (ed.), Hamburg: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2006, p. 83. In some Reichsgaue in 1942 and 1943, privileged mixed couples, and their minor children whose father was classified as a Jew, were forced to move into houses reserved for Jews only; this effectively made a privileged mixed marriage one where the husband was the one classified as so-called 'Aryan'.

The inconsistent application of ''privileged mixed marriages'' led to different compulsions to forced labour in 1940: Sometimes it was ordered for all Jewish-classified spouses, sometimes for Jewish-classified husbands, sometimes exempting Jewish-classified wives taking care of minor children. No document or law indicated the exemption of a mixed marriage from some persecutions and especially of its Jewish-classified spouse. Thus if arrested, non-arrested relatives or friends had to prove their exemption status, hopefully fast enough to rescue the arrested from any deportation.

Systematic deportations of Jewish Germans and Gentile Germans of Jewish descent started on 18 October 1941. German Jews and German Gentiles of Jewish descent living in ''mixed marriage'' were in fact mostly spared from deportation. In case a mixed marriage ended by death of the 'Aryan' spouse or divorce, the Jewish-classified spouse residing within Germany was usually deported soon after, unless the couple still had minor children not counting as Geltungsjuden.

In March 1943, an attempt to deport the Berlin-based Jews and Gentiles of Jewish descent living in non-privileged mixed marriages, failed due to public protest by their relatives-in-law of 'Aryan kinship' (see Rosenstrasse protest). Also, the Aryan-classified husbands and Mischling-classified children (starting at the age of 16) from mixed marriages were taken by the Organisation Todt

Organisation Todt (OT; ) was a Civil engineering, civil and military engineering organisation in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945, named for its founder, Fritz Todt, an engineer and senior member of the Nazi Party. The organisation was responsible ...

for forced labour, starting in autumn 1944.

A last attempt, undertaken in February/March 1945 ended, because the extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe, primarily in occupied Poland, during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocau ...

s already were liberated. However, 2,600 from all areas of the Reich, not yet captured by the Allies, were deported to Theresienstadt

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ( German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstadt served as a waystation to the extermination c ...

, of whom most survived the last months until their liberation.

With the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945 the laws banning mixed marriages were lifted again. Marriage dates could be backdated, if so desired, for couples who lived together unmarried during the Nazi era due to the legal restrictions, upon marrying after the war. Even if one spouse was already dead, the marriage could be retroactively recognised, in order to legitimise any children and enable them or the surviving spouse to inherit from their late father or partner, respectively. In the West German Federal Republic of Germany 1,823 couples applied for recognition (until 1963), which was granted in 1,255 cases.

France

In 1723, 1724 and 1774 several administrative acts forbade interracial marriages, mainly in colonies, although it is not clear if these acts were lawful. On 2 May 1746, theParlement de Paris

The ''Parlement'' of Paris () was the oldest ''parlement'' in the Kingdom of France, formed in the 14th century. Parlements were judicial, rather than legislative, bodies and were composed of magistrates. Though not representative bodies in the p ...

validated an interracial marriage.

Under King Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir-apparent of King Louis XV), and Mari ...

, the order of the Conseil du Roi

The (; 'King's Council'), also known as the Royal Council, is a general term for the administrative and governmental apparatus around the King of France during the Ancien Régime designed to prepare his decisions and to advise him. It should no ...

of 5 April 1778, signed by Antoine de Sartine

Antoine Raymond Jean Gualbert Gabriel de Sartine, comte d'Alby (; 12 July 1729 – 7 September 1801) was a French statesman who served as Lieutenant General of Police of Paris (1759–1774) during the reign of Louis XV and as Secretary of Stat ...

, forbade "whites of either sex to contract marriage with blacks, mulatto

( , ) is a Race (human categorization), racial classification that refers to people of mixed Sub-Saharan African, African and Ethnic groups in Europe, European ancestry only. When speaking or writing about a singular woman in English, the ...

s or other people of color" in the Kingdom, as the number of blacks had increased so much in France, mostly in the capital. Nevertheless, it was an interracial marriage prohibition, not an interracial sex prohibition. Moreover, it was an administrative act, not a law. There was never any racial law about marriage in France, with the exception of French Louisiana

The term French Louisiana ( ; ) refers to two distinct regions:

* First, to Louisiana (New France), historic French Louisiana, comprising the massive, middle section of North America claimed by Early Modern France, France during the 17th and 18th ...

. But some restricted rules were applied about heritage

Heritage may refer to:

History and society

* A heritage asset A heritage asset is an item which has value because of its contribution to a nation's society, knowledge and/or culture. Such items are usually physical assets, but some countries also ...

and nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

. In any case, nobles needed the King's authorization for their marriage.

On 20 September 1792, all restrictions regarding interracial marriage were repealed by the Revolutionary government. On 8 January 1803, a Napoleonic governmental circular forbade marriages between white males and black women, or black men and white women, although the 1804 Napoleonic code

The Napoleonic Code (), officially the Civil Code of the French (; simply referred to as ), is the French civil code established during the French Consulate in 1804 and still in force in France, although heavily and frequently amended since i ...

did not mention anything specific about interracial marriage. In 1806, a French court validated an interracial marriage. In 1818, the highest French court ('' cour de cassation'') validated a marriage contracted in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

between a white man and a colored woman. All administrative prohibitions were canceled by a law in 1833.

Italy

After thefall

Autumn, also known as fall (especially in US & Canada), is one of the four temperate seasons on Earth. Outside the tropics, autumn marks the transition from summer to winter, in September (Northern Hemisphere) or March ( Southern Hemispher ...

of the Western Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

in the late 5th century, the Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths () were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Western Roman Empire, drawing upon the large Gothic populatio ...

under the Theodoric the Great

Theodoric (or Theoderic) the Great (454 – 30 August 526), also called Theodoric the Amal, was king of the Ostrogoths (475–526), and ruler of the independent Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy between 493 and 526, regent of the Visigoths (511–526 ...

established the Ostrogothic Kingdom

The Ostrogothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of Italy (), was a barbarian kingdom established by the Germanic Ostrogoths that controlled Italian peninsula, Italy and neighbouring areas between 493 and 553. Led by Theodoric the Great, the Ost ...

at Ravenna

Ravenna ( ; , also ; ) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire during the 5th century until its Fall of Rome, collapse in 476, after which ...

, ruling Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

as a dominant minority

A dominant minority, also called elite dominance, is a minority group that has overwhelming political power, political, economic power, economic, or cultural dominance in a country, despite representing a small fraction of the overall populatio ...

. In order to prevent the Romanization

In linguistics, romanization is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Latin script, Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and tra ...

of his people, Theodoric forbade intermarriage between Goths

The Goths were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe. They were first reported by Graeco-Roman authors in the 3rd century AD, living north of the Danube in what is ...

and Romans. Theodoric's effort to separate Goths and Romans was however not successful, as intermarriages and assimilation were common. The Rugii

The Rugii, Rogi or Rugians (), were one of the smaller Germanic peoples of Late Antiquity who are best known for their short-lived 5th-century kingdom upon the Roman frontier, near present-day Krems an der Donau in Austria. This kingdom, like t ...

, a Germanic tribe which supported Theodoric while preserving its independence within the Ostrogothic Kingdom, avoided intermarriage with Goths and other tribes in order to maintain administrative control.

After the publication of the Charter of Race in Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

, laws prohibiting marriage between Italians and non-Europeans were passed in Italy and its colonies. A Grand Council's resolution reiterated the prohibition of marriage between Italians and people belonging to "Hamitic, Semitic, and other non-Aryan races"; it established also a ban on marriage between public servants and foreigners. A list made in summer 1938 classified Negroes

In the English language, the term ''negro'' (or sometimes ''negress'' for a female) is a term historically used to refer to people of Black African heritage. The term ''negro'' means the color black in Spanish and Portuguese (from Latin ''niger ...

, Arabs and Berbers, Mongolians, Indians, Armenians, Turks, Yemenites, Palestinians as non-Aryans.

An analogous legislation was adopted in 1942 in the fascist Republic of San Marino.

Pre-Islamic Iberia

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century, theVisigoths

The Visigoths (; ) were a Germanic people united under the rule of a king and living within the Roman Empire during late antiquity. The Visigoths first appeared in the Balkans, as a Roman-allied Barbarian kingdoms, barbarian military group unite ...

established the Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, Visigothic Spain or Kingdom of the Goths () was a Barbarian kingdoms, barbarian kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic people ...

in Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

, ruling the peninsula as a dominant minority. The Visigoths were subjected to their own legal code

A code of law, also called a law code or legal code, is a systematic collection of statutes. It is a type of legislation that purports to exhaustively cover a complete system of laws or a particular area of law as it existed at the time the co ...

, and were forbidden from intermarrying with indigenous Iberians. This law was abolished in the end of the 6th century however, and by that time so many intermarriages had occurred that any reality of a biologically-linked Visigothic identity were "visibly crumbling", in the words of Gavin Langmuir. The Visigothic nobles and princes married Hispano-Romans and converted to Nicean Christianity, and the connection between Visigoths, their religion and royal authority became obscure.

British colonies

In 1909, the British Colonial Office published a circular known as the "Concubine Circular", officially denouncing officials who kept native mistresses, accusing them of "lowering" themselves in the eyes of the native population. Some colonial officials such as Hugh Clifford, in his 1898 novel ''Since the Beginning: A tale of an Eastern Land'', attempted to defend their relationships with native women as being purely physical, while their relationship with a white wife was "purer". The 1909 circular was part of a wider British movement to maintain an "imperial race" kept at a distance from the native population. However, these efforts did not amount to a rigorous effort to eradicate such practices due to the large number of officials who engaged in such relationships.See also

* Amalgamation (history) *Endogamy

Endogamy is the cultural practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting any from outside of the group or belief structure as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relatio ...

*History of Bob Jones University

Evangelist Bob Jones Sr. founded Bob Jones University out of concern with the secularization of higher education. BJU has had seven presidents: Bob Jones Sr. (1927–1947); Bob Jones Jr. (1947–1971); Bob Jones III (1971–2005); Stephen Jones (ad ...

*Historical race concepts

The concept of race (human categorization), race as a categorization of anatomically modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') has an extensive history in Europe and the Americas. The contemporary word ''race'' itself is modern; historically it was used ...

*Hypodescent

In societies that regard some races or ethnic groups of people as dominant or superior and others as subordinate or inferior, hypodescent refers to the automatic assignment of children of a mixed union to the subordinate group. The opposite pract ...

*Judicial aspects of race in the United States

Legislation seeking to direct relations between racial or ethnic groups in the United States has had several historical phases, developing from the European colonization of the Americas, the triangular slave trade, and the American Indian Wars ...

*Loving Day

Loving Day is an annual celebration held on June 12, the anniversary of the 1967 United States Supreme Court decision ''Loving v. Virginia'' that struck down all anti-miscegenation laws remaining in sixteen U.S. states. In the United States, ...

*Mixed Race Day

In Brazil, "Mixed Race Day" (''Dia do Mestiço'') is observed annually on June 27, three days after the Day of the Caboclo, in celebration of all mixed-race Brazilians, including the caboclos. The date is an official public holiday in three Braz ...

*One drop rule

The one-drop rule was a legal principle of racial classification that was prominent in the 20th-century United States. It asserted that any person with even one ancestor of African ancestry ("one drop" of "black blood")Davis, F. James. Frontl ...

* Race of the future

*Racial hygiene

The term racial hygiene was used to describe an approach to eugenics in the early 20th century, which found its most extensive implementation in Nazi Germany (Nazi eugenics). It was marked by efforts to avoid miscegenation, analogous to an anim ...

*Scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

*Social interpretations of race

Race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 16th century, when it was used to refer to groups of va ...

References

Bibliography

*Further reading

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Anti-Miscegenation Laws Racism Interracial marriage Politics and race Marriage reform Racial segregation