Anti-Fascist Network on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-fascism is a

A

A

and the Italian Anarchist Union emerged between 1919 and 1921, to combat the nationalist and fascist surge of the post-World War I period. In the words of historian

"The First American Anti-Nazi Film, Rediscovered"

''

Anti-fascist movements emerged first in Italy during the rise of

Anti-fascist movements emerged first in Italy during the rise of

In Italy, Mussolini's

In Italy, Mussolini's

Clash of civilisations

, Italian Historical Society Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, p. 4 By the mid-1930s, 70,000 Slovenes had fled Italy, mostly to

The historian

The historian

In the 1920s and 1930s in the

In the 1920s and 1930s in the

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the

The Anti-Fascist Bloc was an organization of

The Anti-Fascist Bloc was an organization of

The anti-fascist movements which emerged during the period of classical fascism, both liberal and militant, continued to operate after the defeat of the

The anti-fascist movements which emerged during the period of classical fascism, both liberal and militant, continued to operate after the defeat of the  The war ends in Italy on 2 May 1945, with the complete surrender of

The war ends in Italy on 2 May 1945, with the complete surrender of

Today's

Today's  '' Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia'' (ANPI; "National Association of Italian

'' Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia'' (ANPI; "National Association of Italian

'Fascism or Revolution!' Anarchism and Antifascism in France, 1933–39

''Contemporary European History'' Volume 8, Issue 1 March 1999, pp. 51–71 * * Brasken, Kasper.

Making Anti-Fascism Transnational: The Origins of Communist and Socialist Articulations of Resistance in Europe, 1923–1924

" ''Contemporary European History'' 25.4 (2016): 573–596. * * Brinks, J. H. “Political Anti-Fascism in the German Democratic Republic.” Journal of Contemporary History 32, no. 2 (1997): 207–17

* * Class War/3WayFight/Kate Sharpley Librar

Interview from ''Beating Fascism: Anarchist Anti-Fascism in Theory and Practice''

anarkismo.net * Copsey, N. (2011) "From direct action to community action: The changing dynamics of anti-fascist opposition", in * Nigel Copsey & Andrzej Olechnowicz (eds.),

Varieties of Anti-fascism. Britain in the Inter-war Period

', Palgrave Macmillan * Gilles Dauvé

Fascism/Antifascism

", libcom.org * David Featherstone

Black Internationalism, Subaltern Cosmopolitanism, and the Spatial Politics of Antifascism

''Annals of the Association of American Geographers'' Volume 103, 2013, Issue 6, pp. 1406–1420 * Fisher, David James. “Malraux: Left Politics and Anti-Fascism in the 1930’s.” Twentieth Century Literature 24, no. 3 (1978): 290–302

* Joseph Froncza

"Local People's Global Politics: A Transnational History of the Hands Off Ethiopia Movement of 1935"

''Diplomatic History'', Volume 39, Issue 2, 1 April 2015, pp. 245–274 * Hugo Garcia, ed,

Transnational Anti-Fascism: Agents, Networks, Circulations'' ''Contemporary European History

' Volume 25, Issue 4 November 2016, pp. 563–572 * Gottfried, Paul. Antifascism: The Course of a Crusade. Cornell University Press, 2021

* * Renton, Dave.

Fascism, Anti-fascism and Britain in the 1940s

'. Springer, 2016. * * Enzo Traverso]

"Intellectuals and Anti-Fascism: For a Critical Historization"

''New Politics'', vol. 9, no. 4 (new series), whole no. 36, Winter 2004 *

United Front Against Fascism records

1945-2021. At th

Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections

Centre for fascist, anti-fascist and post-fascist studies

– Teesside University (archived 24 August 2017)

Remembering the Anarchist Resistance to fascism

{{DEFAULTSORT:Anti-Fascism Anti-fascism, Political movements

political movement

A political movement is a collective attempt by a group of people to change government policy or social values. Political movements are usually in opposition to an element of the status quo, and are often associated with a certain ideology. Some t ...

in opposition to fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, where the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

were opposed by many countries forming the Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international Coalition#Military, military coalition formed during World War II (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers. Its principal members were the "Four Policeme ...

and dozens of resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized group of people that tries to resist or try to overthrow a government or an occupying power, causing disruption and unrest in civil order and stability. Such a movement may seek to achieve its goals through ei ...

s worldwide. Anti-fascism has been an element of movements across the political spectrum and holding many different political positions such as anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

, communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ...

, republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

, social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

, socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

and syndicalism

Syndicalism is a labour movement within society that, through industrial unionism, seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through Strike action, strikes and other forms of direct action, with the eventual goa ...

as well as centrist

Centrism is the range of political ideologies that exist between left-wing politics and right-wing politics on the left–right political spectrum. It is associated with moderate politics, including people who strongly support moderate policie ...

, conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

, liberal and nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

viewpoints.

Fascism, a far-right

Far-right politics, often termed right-wing extremism, encompasses a range of ideologies that are marked by ultraconservatism, authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and nativism. This political spectrum situates itself on the far end of the ...

ultra-nationalistic

Ultranationalism, or extreme nationalism, is an extremist form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains hegemony, supremacy, or other forms of control over other nations (usually through violent coercion) to pursue its specific i ...

ideology best known for its use by the Italian Fascists

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

and the German Nazis

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

, became prominent beginning in the 1910s. Organization against fascism began around 1920. Fascism became the state ideology of Italy in 1922 and of Germany in 1933, spurring a large increase in anti-fascist action, including German resistance to Nazism

The German resistance to Nazism () included unarmed and armed opposition and disobedience to the Nazi Germany, Nazi regime by various movements, groups and individuals by various means, from assassination attempts on Adolf Hitler, attempts to ass ...

and the Italian resistance movement

The Italian Resistance ( ), or simply ''La'' , consisted of all the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social Republic during the Second World War in Italy ...

. Anti-fascism was a major aspect of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

, which foreshadowed World War II.

Before World War II, the West

West is a cardinal direction or compass point.

West or The West may also refer to:

Geography and locations

Global context

* The Western world

* Western culture and Western civilization in general

* The Western Bloc, countries allied with NAT ...

had not taken seriously the threat of fascism, and anti-fascism was sometimes associated with communism. However, the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies and the Axis powers. Nearly all of the world's countries participated, with many nations mobilisin ...

greatly changed Western perceptions, and fascism was seen as an existential threat by not only the communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

Soviet Union but also by the liberal-democratic

Liberal democracy, also called Western-style democracy, or substantive democracy, is a form of government that combines the organization of a democracy with ideas of liberal political philosophy. Common elements within a liberal democracy are: ...

United States and United Kingdom. The Axis Powers of World War II were generally fascist, and the fight against them was characterized in anti-fascist terms. Resistance during World War II

During World War II, resistance movements operated in German-occupied Europe by a variety of means, ranging from non-cooperation to propaganda, hiding crashed pilots and even to outright warfare and the recapturing of towns. In many countries, r ...

to fascism occurred in every occupied country, and came from across the ideological spectrum. The defeat of the Axis powers generally ended fascism as a state ideology.

After World War II, the anti-fascist movement continued to be active in places where organized fascism continued or re-emerged. There was a resurgence of antifa in Germany

Antifa () is a political movement in Germany composed of multiple far-left, Leaderless resistance, autonomous, militant groups and individuals who describe themselves as anti-fascist. According to the German Federal Office for the Protection of ...

in the 1980s, as a response to the invasion of the punk scene

The punk subculture includes a diverse and widely known array of music, ideologies, fashion, and other forms of expression, visual art, dance, literature, and film. Largely characterised by anti-establishment views, the promotion of individual ...

by neo-Nazis

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and racial supremacy (often white supremacy), to att ...

. This influenced the antifa movement in the United States in the late 1980s and 1990s, which was similarly carried by punks. In the 21st century, this greatly increased in prominence as a response to the resurgence of the radical right, especially after the 2016 election of Donald Trump.

Origins

fasces

A fasces ( ; ; a , from the Latin word , meaning 'bundle'; ) is a bound bundle of wooden rods, often but not always including an axe (occasionally two axes) with its blade emerging. The fasces is an Italian symbol that had its origin in the Etrus ...

( ; ; a , from the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

word , meaning 'bundle'; ) is a bound bundle of wooden rods, often but not always including an axe (occasionally two axes) with its blade emerging. The fasces is an Italian symbol that had its origin in the Etruscan civilization

The Etruscan civilization ( ) was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in List of ancient peoples of Italy, ancient Italy, with a common language and culture, and formed a federation of city-states. Af ...

and was passed on to ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

, where it symbolized a Roman king

The king of Rome () was the ruler of the Roman Kingdom, a legendary period of Roman history that functioned as an elective monarchy. According to legend, the first king of Rome was Romulus, who founded the city in 753 BC upon the Palatine H ...

's power to punish his subjects, and later, a magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judi ...

's power

Power may refer to:

Common meanings

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power, a type of energy

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

Math ...

and jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' and 'speech' or 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, the concept of jurisdiction applies at multiple level ...

. They were carried in a procession with a magistrate by lictor

A lictor (possibly from Latin language, Latin ''ligare'', meaning 'to bind') was a Ancient Rome, Roman civil servant who was an attendant and bodyguard to a Roman magistrate, magistrate who held ''imperium''. Roman records describe lictors as hav ...

s, who carried the fasces and at times used the birch rods as punishment to enforce obedience with magisterial commands. In common language and literature, the fasces were regularly associated with certain offices: praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

s were referred to in Greek as the () and the consuls

A consul is an official representative of a government who resides in a foreign country to assist and protect citizens of the consul's country, and to promote and facilitate commercial and diplomatic relations between the two countries.

A consu ...

were referred to as "the twelve fasces" as literary metonymy

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something associated with that thing or concept. For example, the word " suit" may refer to a person from groups commonly wearing business attire, such as sales ...

. Beyond serving as insignia of office, it also symbolised the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

and its prestige.

After the classical period, with the fall of the Roman state, thinkers were removed from the "psychological terror generated by the original Roman fasces" in the antique period. By the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, there emerged a conflation of the fasces with a Greek fable

Fable is a literary genre defined as a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are anthropomorphized, and that illustrates or leads to a parti ...

first recorded by Babrius

Babrius (, ''Bábrios''; ), "Babrius" in '' Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 21. also known as Babrias () or Gabrias (), was the author of a collection of Greek fables, many of which are known today as Aesop's F ...

in the second century AD depicting how individual sticks can be easily broken but how a bundle could not be. This story is common across Eurasian culture and by the thirteenth century AD was recorded in the ''Secret History of the Mongols

The ''Secret History of the Mongols'' is the oldest surviving literary work in the Mongolic languages. Written for the Mongol royal family some time after the death of Genghis Khan in 1227, it recounts his life and conquests, and partially the r ...

''. While there is no historical connection between the original fasces and this fable, by the sixteenth century AD, fasces were "inextricably linked" with interpretations of the fable as one expressing unity and harmony. Italian Fascism

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

, which derives its name from the fasces, arguably used this symbolism the most in the 20th century.

With the development and spread of Italian Fascism, i.e. the original fascism, the National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party (, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian fascism and as a reorganisation of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The party ruled the Kingdom of It ...

's ideology was met with increasingly militant opposition by Italian communists and socialists. Organizations such as ''Arditi del Popolo

The ''Arditi del Popolo'' () was an Italian militant anti-fascist group founded at the end of June 1921 to resist the rise of Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party and the violence of the Blackshirts (''squadristi'') paramilitaries.

''Gli Arditi del Popolo (Birth)and the Italian Anarchist Union emerged between 1919 and 1921, to combat the nationalist and fascist surge of the post-World War I period. In the words of historian

Eric Hobsbawm

Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm (; 9 June 1917 – 1 October 2012) was a British historian of the rise of industrial capitalism, socialism and nationalism. His best-known works include his tetralogy about what he called the "long 19th century" (''Th ...

, as fascism developed and spread, a "nationalism of the left" developed in those nations threatened by Italian irredentism

Irredentism () is one State (polity), state's desire to Annexation, annex the territory of another state. This desire can be motivated by Ethnicity, ethnic reasons because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to or the same as the ...

(e.g. in the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, and Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

in particular). After the outbreak of World War II, the Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

and Yugoslav resistances were instrumental in antifascist action and underground resistance. This combination of irreconcilable nationalisms and leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social hierarchies. Left-wing politi ...

partisans constitute the earliest roots of European anti-fascism. Less militant forms of anti-fascism arose later. During the 1930s in Britain, "Christians – especially the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

– provided both a language of opposition to fascism and inspired anti-fascist action". French philosopher Georges Bataille

Georges Albert Maurice Victor Bataille (; ; 10 September 1897 – 8 July 1962) was a French philosopher and intellectual working in philosophy, literature, sociology, anthropology, and history of art. His writing, which included essays, novels, ...

believed that Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

was a forerunner of anti-fascism due to his derision for nationalism and racism.

Michael Seidman argues that traditionally anti-fascism was seen as the purview of the political left

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social hierarchies. Left-wing politi ...

but that in recent years this has been questioned. Seidman identifies two types of anti-fascism, namely revolutionary and counterrevolutionary:

* Revolutionary anti-fascism was expressed amongst communists and anarchists, where it identified fascism and capitalism as its enemies and made little distinction between fascism and other forms of right-wing authoritarianism. It did not disappear after the Second World War but was used as an official ideology of the Soviet bloc, with the "fascist" West as the new enemy.

* Counterrevolutionary anti-fascism was much more conservative in nature, with Seidman arguing that Charles de Gaulle and Winston Churchill represented examples of it and that they tried to win the masses to their cause. Counterrevolutionary antifascists desired to ensure the restoration or continuation of the prewar old regime and conservative antifascists disliked fascism's erasure of the distinction between the public and private spheres. Like its revolutionary counterpart, it would outlast fascism once the Second World War ended.

Seidman argues that despite the differences between these two strands of anti-fascism, there were similarities. They would both come to regard violent expansion as intrinsic to the fascist project. They both rejected any claim that the Versailles Treaty

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace of Versailles, exactl ...

was responsible for the rise of Nazism and instead viewed fascist dynamism as the cause of conflict. Unlike fascism, these two types of anti-fascism did not promise a quick victory but an extended struggle against a powerful enemy. During World War II, both anti-fascisms responded to fascist aggression by creating a cult of heroism which relegated victims to a secondary position.Seidman, Michael. Transatlantic Antifascisms: From the Spanish Civil War to the End of World War II. Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp.1–8 However, after the war, conflict arose between the revolutionary and counterrevolutionary anti-fascisms; the victory of the Western Allies allowed them to restore the old regimes of liberal democracy in Western Europe, while Soviet victory in Eastern Europe allowed for the establishment of new revolutionary anti-fascist regimes there.

Counterrevolutionary anti-fascism

Counterrevolutionary anti-fascism, also known as conservative and liberal anti-fascism, refers to the opposition to fascism grounded in the defense of democracy, constitutional order, and traditional institutions. Unlike revolutionary anti-fascism, which aims for social and political transformation, counterrevolutionary anti-fascism is focused on preserving or restoring pre-war political systems, such as constitutional monarchies and republics based on Enlightenment ideals. This form of anti-fascism is often associated with prominent figures such asFranklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

and Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

, who opposed fascist authoritarianism while also resisting revolutionary movements that sought to radically change society. It was supported by a broad coalition of groups, including capitalists, trade unionists, social democrats, and traditionalists, all of whom united in their opposition to fascism and their support for political stability.

Counterrevolutionary anti-fascism sought to challenge fascist ideologies and movements, aiming to preserve existing democratic structures and stabilize society. It focused on reinforcing confidence in democratic governance and addressing extremist movements, setting itself apart from revolutionary anti-fascism, which frequently aimed at challenging capitalist systems.

In Britain, conservative anti-fascism primarily concentrated on maintaining democratic governance and marginalizing fascist groups through legal and institutional means. Liberal anti-fascism, on the other hand, opposed fascism through media campaigns, petitions, parliamentary debates, and public discourse. Both forms recognized fascism as a threat to state stability, and both approached revolutionary ideologies, including communism, with caution. British counterrevolutionary anti-fascism in the 1930s was shaped by an alliance that transcended traditional political divisions. Churchill's leadership was pivotal in creating an antifascist front that included both conservative and social democratic figures. This coalition rejected the idea that fascism was the only way to prevent communism and instead promoted a defense of "ordered freedom," which emphasized representative democracy, religious tolerance, and private property. Through organizations like the Anti-Nazi Council, the counterrevolutionary antifascist movement rallied elites across the political spectrum, including trade unionists and churchmen, to oppose fascism and preserve liberal democracy. This broader vision of antifascism, distinct from Marxist and communist approaches, helped shape Britain’s resistance to Nazi aggression.

French counterrevolutionary anti-fascism, particularly in the years leading up to and during World War II, was characterized by opposition to both Italian Fascism and German Nazism. Figures such as Benjamin Crémieux

Benjamin Crémieux (1888–1944) was a French author, critic and literary historian.

Early life

Crémieux was born to a Jewish family in Narbonne, France in 1888. His family had long ties in the region, having 'settled in France as early as th ...

, a Jewish intellectual, criticized Mussolini's anti-parliamentarianism and the Fascist regime's approach to democracy, expressing concern about a potential alignment between Italian Fascism and far-right movements in France. Meanwhile, journals like L’Europe Nouvelle and individuals such as Georges Bernanos

Louis Émile Clément Georges Bernanos (; 20 February 1888 – 5 July 1948) was a French author, and a soldier in World War I. A Catholic with monarchist leanings, he was critical of elitist thought and was opposed to what he identified as d ...

and Charles de Gaulle opposed the policy of appeasement, emphasizing the potential dangers of Fascism's totalitarianism. They also critiqued the French right’s minimization of the threats posed by Hitler and Mussolini and advocated for an anti-fascist stance, which, in some cases, included support for alliances with the Soviet Union despite differing views on Communism. This counterrevolutionary anti-fascism was influenced by concerns over national sovereignty, democracy, and resistance to totalitarian movements.

In the United States, a coalition of liberals and conservatives, particularly under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, opposed fascism through both political and military means, with an emphasis on preserving democratic institutions in the face of growing fascist threats. American counterrevolutionary anti-fascism emerged as a response to the increasing spread of fascism in Europe and the potential for its expansion into the Western Hemisphere. Initially, Roosevelt navigated a delicate balance, adopting limited measures to avoid alienating isolationist sentiment while preparing for the possibility of war. As Germany's expansion progressed, Roosevelt shifted towards providing more active support for Britain and its allies, eventually securing public and political backing for military aid. Despite opposition from isolationists and anti-interventionists, Roosevelt's administration, supported by business and labor leaders, increasingly aligned with anti-fascist forces. This shift in American foreign policy reinforced the country's focus on countering Nazi Germany, reducing the influence of isolationists, and establishing an anti-fascist position. Examples of anti-fascist propaganda in the United States are the films '' Hitler's Reign of Terror'' (1934), often credited as being the "first-ever American anti-Nazi film,"Greenhouse, Emily (May 21, 2013"The First American Anti-Nazi Film, Rediscovered"

''

The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

''. Accessed: March 5, 2015. and '' Don't Be a Sucker'' (1943).

History

Anti-fascist movements emerged first in Italy during the rise of

Anti-fascist movements emerged first in Italy during the rise of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

, but they soon spread to other European countries and then globally. In the early period, Communist, socialist, anarchist and Christian workers and intellectuals were involved. Until 1928, the period of the United front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political and/ ...

, there was significant collaboration between the Communists and non-Communist anti-fascists.

In 1928, the Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

instituted its ultra-left

In Marxism, ultra-leftism encompasses a broad spectrum of revolutionary Marxist currents that are anti-Leninist in perspective. Ultra-leftism distinguishes itself from other left-wing currents through its rejection of electoralism, trade unioni ...

Third Period

The Third Period is an ideological concept adopted by the Communist International (Comintern) at its Sixth World Congress, held in Moscow in the summer of 1928. It set policy until reversed when the Nazis took over Germany in 1933.

The Cominte ...

policies, ending co-operation with other left groups, and denouncing social democrats as "social fascists

Social fascism was a theory developed by the Communist International (Comintern) in the early 1930s which saw social democracy as a moderate variant of fascism.

The Comintern argued that capitalism had entered a Third Period in which proletaria ...

". From 1934 until the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact and the Nazi–Soviet Pact, was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Ge ...

, the Communists pursued a Popular Front approach, of building broad-based coalitions with liberal and even conservative anti-fascists. As fascism consolidated its power, and especially during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, anti-fascism largely took the form of partisan

Partisan(s) or The Partisan(s) may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

** Francs-tireurs et partisans, communist-led French anti-fascist resistance against Nazi Germany during WWII

** Ital ...

or resistance movements.

Italy: against Fascism and Mussolini

Fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

regime used the term ''anti-fascist'' to describe its opponents. Mussolini's secret police

image:Putin-Stasi-Ausweis.png, 300px, Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 1985 to 1989. Both organizations used similar forms of repression.

Secre ...

was officially known as the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism

The OVRA, unofficially known as the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism (), was the secret police of the Kingdom of Italy during the reign of King Victor Emmanuel III. It was founded in 1927 under the regime of Italian fas ...

. During the 1920s in the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

, anti-fascists, many of them from the labor movement

The labour movement is the collective organisation of working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It can be considere ...

, fought against the violent Blackshirts

The Voluntary Militia for National Security (, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts (, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the National Fascist Party, known as the Squadrismo, and after 1923 an all-vo ...

and against the rise of the fascist leader Benito Mussolini. After the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

(PSI) signed a pacification pact with Mussolini and his Fasces of Combat on 3 August 1921, and trade unions adopted a legalist and pacified strategy, members of the workers' movement who disagreed with this strategy formed ''Arditi del Popolo

The ''Arditi del Popolo'' () was an Italian militant anti-fascist group founded at the end of June 1921 to resist the rise of Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party and the violence of the Blackshirts (''squadristi'') paramilitaries.

''.

The Italian General Confederation of Labour

The Italian General Confederation of Labour (, , CGIL ) is a national trade union centre in Italy. It was formed by an agreement between socialists, communists, and Christian democrats in the "Pact of Rome" of June 1944. In 1950, socialists and ...

(CGL) and the PSI refused to officially recognize the anti-fascist militia and maintained a non-violent, legalist strategy, while the Communist Party of Italy

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

(PCd'I) ordered its members to quit the organization. The PCd'I organized some militant groups, but their actions were relatively minor. The Italian anarchist Severino Di Giovanni

Severino Di Giovanni (17 March 1901 – 1 February 1931) was an Italian anarchist who immigrated to Argentina, where he became the best-known anarchist figure in that country for his campaign of violence in support of Sacco and Vanzetti and an ...

, who exiled himself to Argentina following the 1922 March on Rome

The March on Rome () was an organized mass demonstration in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (, PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, Fascist Party leaders planned a march ...

, organized several bombings against the Italian fascist community. The Italian liberal anti-fascist Benedetto Croce

Benedetto Croce, ( , ; 25 February 1866 – 20 November 1952)

was an Italian idealist philosopher, historian, and politician who wrote on numerous topics, including philosophy, history, historiography, and aesthetics. A Cultural liberalism, poli ...

wrote his ''Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals

The Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals, written by Benedetto Croce in response to the Manifesto of the Fascist Intellectuals by Giovanni Gentile, sanctioned the irreconcilable split between the philosopher and the Fascist government of ...

'', which was published in 1925. Other notable Italian liberal anti-fascists around that time were Piero Gobetti

Piero Gobetti (; 19 June 1901 – 15 February 1926) was an Italian journalist, intellectual, and anti-fascist. A radical and revolutionary liberal, he was an exceptionally active campaigner and critic in the crisis years in Italy after the Fir ...

and Carlo Rosselli

Carlo Alberto Rosselli (16 November 18999 June 1937) was an Italian political leader, journalist, historian, philosopher and anti-fascist activist, first in Italy and then abroad. He developed a theory of reformist, non-Marxist socialism inspir ...

.

Concentrazione Antifascista Italiana

(CAI; Italian Anti-Fascist Concentration), officially known as (Anti-Fascist Action Concentration), was an Italian coalition of anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. B ...

(), officially known as Concentrazione d'Azione Antifascista (Anti-Fascist Action Concentration), was an Italian coalition of Anti-Fascist groups which existed from 1927 to 1934. Founded in Nérac

Nérac (; , ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Lot-et-Garonne Departments of France, department, Southwestern France. The composer and organist Louis Raffy was born in Nérac, as was the former Arsenal F.C., Arsenal and FC Girondins de Bo ...

, France, by expatriate Italians, the CAI was an alliance of non-communist anti-fascist forces (republican, socialist, nationalist) trying to promote and to coordinate expatriate actions to fight fascism in Italy; they published a propaganda paper entitled ''La Libertà''.

Giustizia e Libertà

Giustizia e Libertà (; ) was an Italian anti-fascist resistance movement, active from 1929 to 1945.James D. Wilkinson (1981). ''The Intellectual Resistance Movement in Europe''. Harvard University Press. p. 224. The movement was cofounded by ...

() was an Italian anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized group of people that tries to resist or try to overthrow a government or an occupying power, causing disruption and unrest in civil order and stability. Such a movement may seek to achieve its goals through ei ...

, active from 1929 to 1945.James D. Wilkinson (1981). ''The Intellectual Resistance Movement in Europe''. Harvard University Press. p. 224. The movement was cofounded by Carlo Rosselli

Carlo Alberto Rosselli (16 November 18999 June 1937) was an Italian political leader, journalist, historian, philosopher and anti-fascist activist, first in Italy and then abroad. He developed a theory of reformist, non-Marxist socialism inspir ...

, Ferruccio Parri

Ferruccio Parri (; 19 January 1890 – 8 December 1981) was an Italian partisan and anti-fascist politician who served as the 29th Prime Minister of Italy, and the first to be appointed after the end of World War II. During the war, he was also ...

, who later became Prime Minister of Italy

The prime minister of Italy, officially the president of the Council of Ministers (), is the head of government of the Italy, Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is established by articles 92–96 of the Co ...

, and Sandro Pertini

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio "Sandro" Pertini (; 25 September 1896 – 24 February 1990) was an Italian socialist politician and statesman who served as President of Italy from 1978 to 1985.

Early life

Born in Stella (province of Savona) as t ...

, who became President of Italy

The president of Italy, officially titled President of the Italian Republic (), is the head of state of Italy. In that role, the president represents national unity and guarantees that Politics of Italy, Italian politics comply with the Consti ...

, were among the movement's leaders. The movement's members held various political beliefs but shared a belief in active, effective opposition to fascism, compared to the older Italian anti-fascist parties. ''Giustizia e Libertà'' also made the international community aware of the realities of fascism in Italy, thanks to the work of Gaetano Salvemini

Gaetano Salvemini (; 8 September 1873 – 6 September 1957) was an Italian socialist and anti-fascist politician, historian, and writer. Born into a family of modest means, he became a historian of note whose work drew attention in Italy and ab ...

.

Many Italian anti-fascists participated in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

with the hope of setting an example of armed resistance to Franco

Franco may refer to:

Name

* Franco (name)

* Francisco Franco (1892–1975), Spanish general and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975

* Franco Luambo (1938–1989), Congolese musician, the "Grand Maître"

* Franco of Cologne (mid to late 13th cent ...

's dictatorship against Mussolini's regime; hence their motto: "Today in Spain, tomorrow in Italy".

Between 1920 and 1943, several anti-fascist movements were active among the Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, and History of Slove ...

and Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

in the territories annexed to Italy after World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, known as the Julian March

The Julian March ( Croatian and ), also called Julian Venetia (; ; ; ), is an area of southern Central Europe which is currently divided among Croatia, Italy, and Slovenia.

. The most influential was the militant insurgent organization TIGR

TIGR (an acronym of the place-names ''Trieste, Trst'', ''Istria, Istra'', ''Gorizia, Gorica'', and ''Rijeka, Reka''), fully the Revolutionary Organization of the Julian March T.I.G.R. (), was a Militant (word), militant Anti-fascism, anti-fascis ...

, which carried out numerous sabotages, as well as attacks on representatives of the Fascist Party and the military. Most of the underground structure of the organization was discovered and dismantled by the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism

The OVRA, unofficially known as the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism (), was the secret police of the Kingdom of Italy during the reign of King Victor Emmanuel III. It was founded in 1927 under the regime of Italian fas ...

(OVRA) in 1940 and 1941, and after June 1941 most of its former activists joined the Slovene Partisans

The Slovene Partisans, formally the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Slovenia, were part of Europe's most effective anti-Nazi resistance movement Jeffreys-Jones, R. (2013): ''In Spies We Trust: The Story of Western Intelligence ...

.

During World War II, many members of the Italian resistance

The Italian Resistance ( ), or simply ''La'' , consisted of all the Italy, Italian Resistance during World War II, resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social Republic ...

left their homes and went to live in the mountains, fighting against Italian fascists and German Nazi

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

soldiers during the Italian Civil War

The Italian Civil War (, ) was a civil war in the Kingdom of Italy fought during the Liberation of Italy, Italian campaign of World War II between Italian fascists and Italian resistance movement, Italian partisans (mostly politically organized ...

. Many cities in Italy, including Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

, Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

and Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

, were freed by anti-fascist uprisings.

Slovenians and Croats under Italianization

The anti-fascist resistance emerged within the Slovene minority in Italy (1920–1947), whom the Fascists meant to deprive of their culture, language and ethnicity. The 1920 burning of the National Hall in Trieste, the Slovene center in the multi-cultural and multi-ethnicTrieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

by the Blackshirts, was praised by Benito Mussolini (yet to become Il Duce) as a "masterpiece of the Triestine fascism" (). The use of Slovene in public places, including churches, was forbidden, not only in multi-ethnic areas, but also in the areas where the population was exclusively Slovene. Children, if they spoke Slovene, were punished by Italian teachers who were brought by the Fascist State from Southern Italy

Southern Italy (, , or , ; ; ), also known as () or (; ; ; ), is a macroregion of Italy consisting of its southern Regions of Italy, regions.

The term "" today mostly refers to the regions that are associated with the people, lands or cultu ...

. Slovene teachers, writers, and clergy were sent to the other side of Italy.

The first anti-fascist organization, called TIGR

TIGR (an acronym of the place-names ''Trieste, Trst'', ''Istria, Istra'', ''Gorizia, Gorica'', and ''Rijeka, Reka''), fully the Revolutionary Organization of the Julian March T.I.G.R. (), was a Militant (word), militant Anti-fascism, anti-fascis ...

, was formed by Slovenes and Croats in 1927 in order to fight Fascist violence. Its guerrilla fight continued into the late 1920s and 1930s.Cresciani, Gianfranco (2004Clash of civilisations

, Italian Historical Society Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, p. 4 By the mid-1930s, 70,000 Slovenes had fled Italy, mostly to

Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

(then part of Yugoslavia) and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

.

The Slovene anti-fascist resistance in Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

during World War II was led by Liberation Front of the Slovenian People

The Liberation Front of the Slovene Nation (), or simply Liberation Front (''Osvobodilna fronta'', OF), originally called the Anti-Imperialist Front (''Protiimperialistična fronta'', PIF), was a Slovene anti-fascist political party. The Anti-Imp ...

. The Province of Ljubljana

The Province of Ljubljana (, , ) was the central-southern area of Slovenia. In 1941, it was annexed by the Kingdom of Italy, and after 1943 occupied by Nazi Germany. Created on May 3, 1941, it was abolished on May 9, 1945, when the Slovene Parti ...

, occupied by Italian Fascists, saw the deportation of 25,000 people, representing 7.5% of the total population, filling up the Rab concentration camp

The Rab concentration camp (; ; ) was one of several Italian concentration camps. It was established during World War II, in July 1942, on the Italian-annexed island of Rab (now in Croatia).

According to historians James Walston James Walston ...

and Gonars concentration camp

The Gonars concentration camp was one of the several Italian concentration camps and it was established on February 23, 1942, near Gonars, Italy.

Many prisoners were transferred to this camp from another Italian concentration camp, the Rab co ...

as well as other Italian concentration camps

Italian concentration camps include camps from the Italian colonial wars in Africa as well as camps for the civilian population from areas occupied by Italy during World War II. Memory of both camps were subjected to "historical amnesia". The repr ...

.

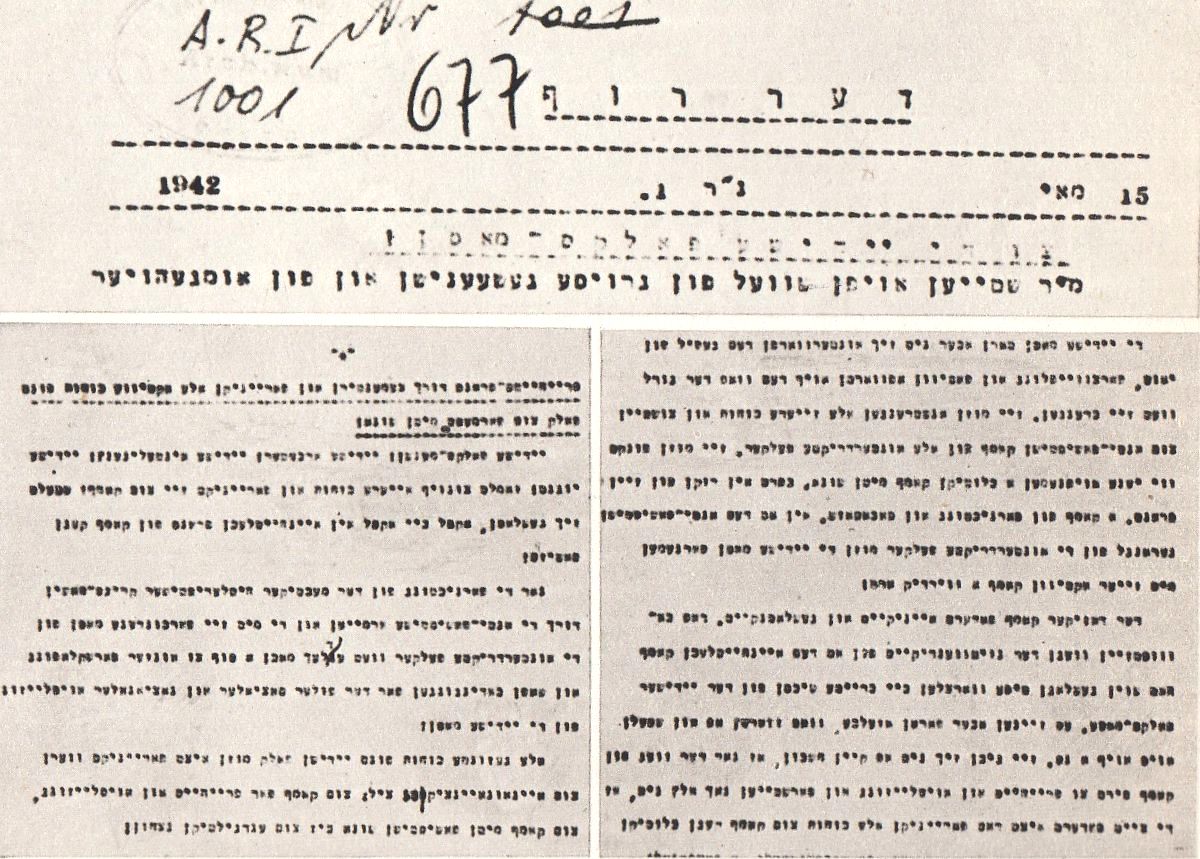

Germany: against the NSDAP and Hitlerism

The specific term anti-fascism was primarily used by theCommunist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (, ; KPD ) was a major Far-left politics, far-left political party in the Weimar Republic during the interwar period, German resistance to Nazism, underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and minor party ...

(KPD), which held the view that it was the only anti-fascist party in Germany. The KPD formed several explicitly anti-fascist groups such as ''Roter Frontkämpferbund

The (, translated as "Alliance of Red Front-Fighters" or "Red Front Fighters' League"), usually called the (RFB), was a far-left paramilitary organization affiliated with the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) during the Weimar Republic. A lega ...

'' (formed in 1924 and banned by the Social Democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

in 1929) and ''Kampfbund gegen den Faschismus'' (a ''de facto'' successor to the latter). At its height, ''Roter Frontkämpferbund'' had over 100,000 members. In 1932, the KPD established the Antifaschistische Aktion

''Antifaschistische Aktion'' (, ) was a communist militant organisation in the Weimar Republic, founded and controlled by the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). ''Antifaschistische Aktion'' opposed anti-Nazi resistance efforts by moderate par ...

as a "red united front under the leadership of the only anti-fascist party, the KPD". Under the leadership of the committed Stalinist

Stalinism (, ) is the totalitarian means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalinism in ...

Ernst Thälmann

Ernst Johannes Fritz Thälmann (; 16 April 1886 – 18 August 1944) was a German communist politician and leader of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) from 1925 to 1933.

A committed communist, Thälmann sought to overthrow the liberal democr ...

, the KPD primarily viewed fascism as the final stage of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

rather than as a specific movement or group, and therefore applied the term broadly to its opponents, and in the name of anti-fascism the KPD focused in large part on attacking its main adversary, the centre-left Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany ( , SPD ) is a social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany. Saskia Esken has been the party's leader since the 2019 leadership election together w ...

, whom they referred to as social fascists

Social fascism was a theory developed by the Communist International (Comintern) in the early 1930s which saw social democracy as a moderate variant of fascism.

The Comintern argued that capitalism had entered a Third Period in which proletaria ...

and regarded as the "main pillar of the dictatorship of Capital."

The movement of Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

, which grew ever more influential in the last years of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

, was opposed for different ideological reasons by a wide variety of groups, including groups which also opposed each other, such as social democrats, centrists, conservatives and communists. The SPD and centrists formed ''Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold

The (, , simply in short) was an organization in Weimar Republic, Germany during the Weimar Republic with the goal to defend German parliamentary democracy against internal subversion and extremism from the left and right and to compel the ...

'' in 1924 to defend liberal democracy

Liberal democracy, also called Western-style democracy, or substantive democracy, is a form of government that combines the organization of a democracy with ideas of liberalism, liberal political philosophy. Common elements within a liberal dem ...

against both the Nazi Party and the KPD, and their affiliated organizations. Later, mainly SPD members formed the Iron Front

The Iron Front () was a German "extraparliamentary" and paramilitary organization in the Weimar Republic which consisted of social democrats, trade unionists, and democratic socialists. Its main goal was to defend democracy against totalita ...

which opposed the same groups.

The name and logo of ''Antifaschistische Aktion'' remain influential. Its two-flag logo, designed by and , is still widely used as a symbol of militant anti-fascists in Germany and globally, as is the Iron Front's Three Arrows

The Three Arrows () is a political symbol associated with the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), used in the late history of the Weimar Republic. First conceived for the SPD-dominated Iron Front as a symbol of the social democratic resi ...

logo.

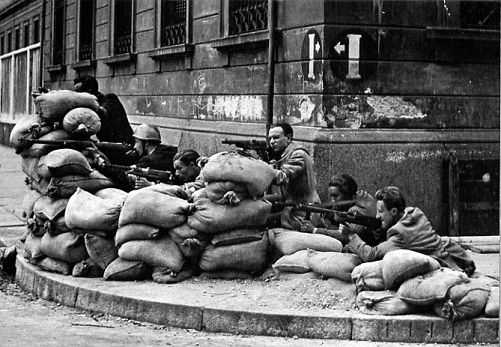

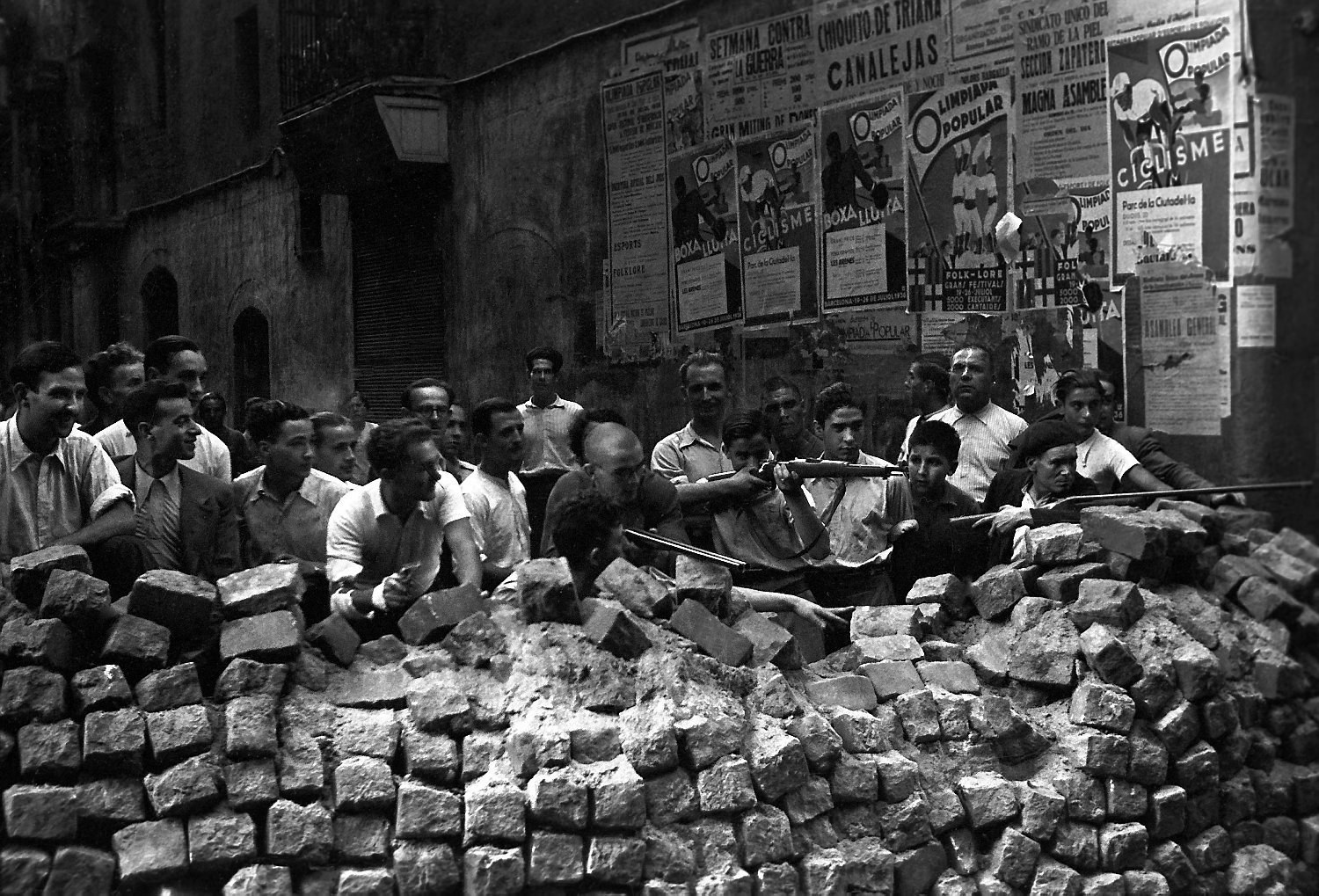

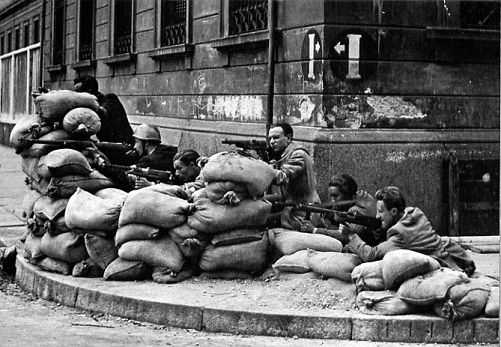

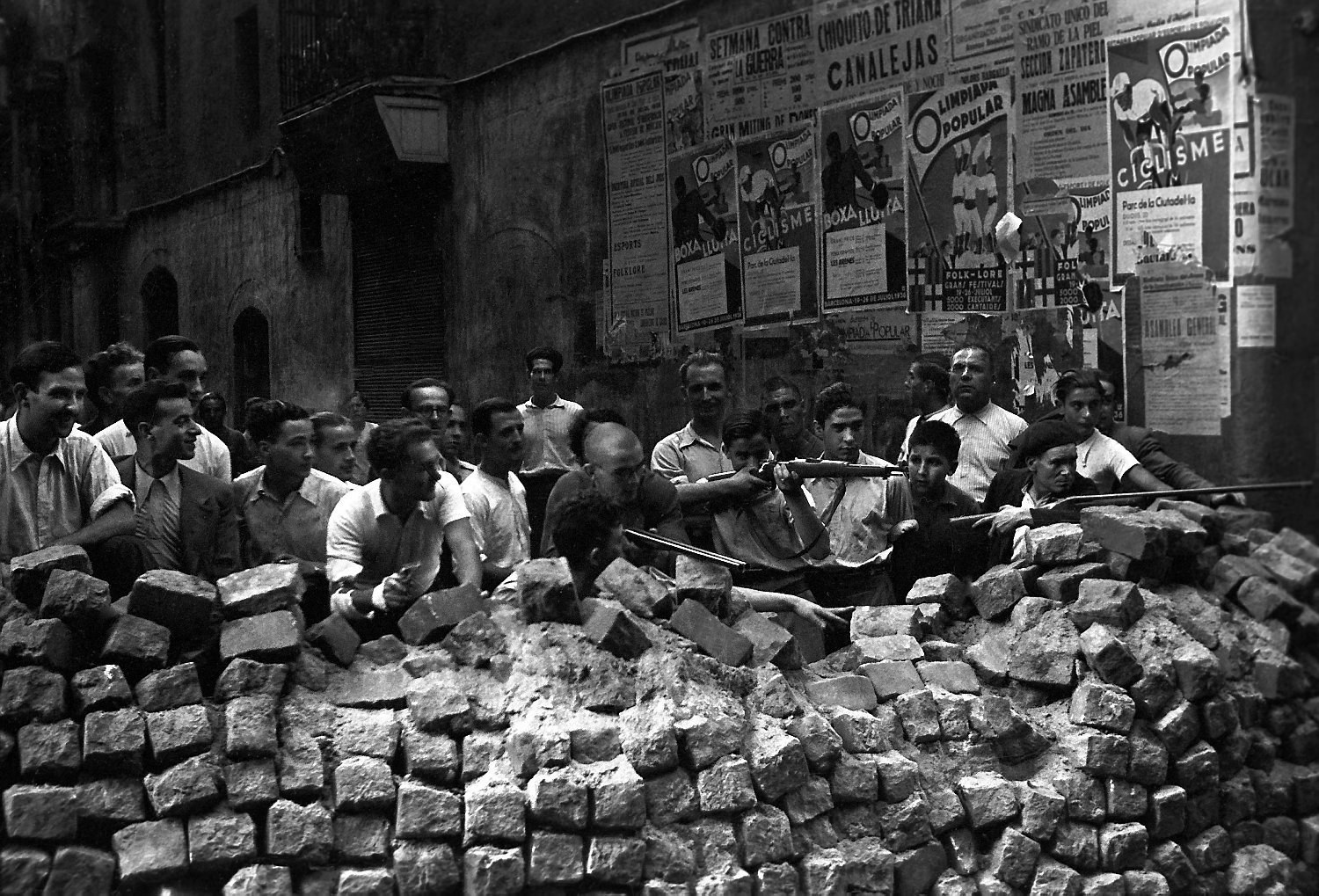

Spain: Civil War against the Nationalists

The historian

The historian Eric Hobsbawm

Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm (; 9 June 1917 – 1 October 2012) was a British historian of the rise of industrial capitalism, socialism and nationalism. His best-known works include his tetralogy about what he called the "long 19th century" (''Th ...

wrote: "The Spanish civil war

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

was both at the centre and on the margin of the era of anti-fascism. It was central, since it was immediately seen as a European war between fascism and anti-fascism, almost as the first battle in the coming world war, some of the characteristic aspects of which – for example, air raids against civilian populations – it anticipated."

In Spain, there were histories of popular uprisings in the late 19th century through to the 1930s against the deep-seated military dictatorships. of General Prim and Primo de Rivera These movements further coalesced into large-scale anti-fascist movements in the 1930s, many in the Basque Country, before and during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

. The republican government and army, the Antifascist Worker and Peasant Militias

The Antifascist Worker and Peasant Militias ({{langx, es, Milicias Antifascistas Obreras y Campesinas, MAOC) were a militia group founded in the Second Spanish Republic in 1934. Their purpose was to protect leaders of the Communist Party of Spai ...

(MAOC) linked to the Communist Party (PCE),De Miguel, Jesús y Sánchez, Antonio: ''Batalla de Madrid,'' in his ''Historia Ilustrada de la Guerra Civil Española.'' Alcobendas, Editorial Libsa, 2006, pp. 189–221. the International Brigades

The International Brigades () were soldiers recruited and organized by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front (Spain), Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The International Bri ...

, the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), Spanish anarchist

Anarchism in Spain has historically gained some support and influence, especially before Francisco Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, when it played an active political role and is considered the end of the golden age of c ...

militias

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or serve ...

, such as the Iron Column

The Iron Column (, ) was a Valencian anarchist militia column formed during the Spanish Civil War to fight against the military forces of the Nationalist Faction that had rebelled against the Second Spanish Republic.

History

The Iron Column ...

and the autonomous governments of Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

and the Basque Country, fought the rise of Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (born Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general and dictator who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces i ...

with military force.

The Friends of Durruti

The Friends of Durruti Group () was a Spanish anarchist group commonly known for its participation in the May Days. Named after Buenaventura Durruti, it was founded on 15 March 1937 by and Félix Martínez, who had become disillusioned with th ...

, associated with the Federación Anarquista Ibérica

The Iberian Anarchist Federation (, FAI) is a Spanish anarchist organization. Due to its close relation with the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) anarcho-syndicalist union, it is often abbreviated as CNT-FAI. The FAI publishes the pe ...

(FAI), were a particularly militant group. Thousands of people from many countries went to Spain in support of the anti-fascist cause, joining units such as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade

The XV International Brigade was one of the International Brigades formed to fight for the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War.

History

The XVth Brigade mustered at Albacete in January 1937. It consisted of English-speaking volunte ...

, the British Battalion

The British Battalion (1936–1938; officially the Shapurji Saklatvala, Saklatvala Battalion) was the 16th (from November 1937 the 57th) battalion of the XV International Brigade, one of the mixed brigades of the International Brigades, during t ...

, the Dabrowski Battalion, the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, the Naftali Botwin Company and the Thälmann Battalion

The Thälmann Battalion was a battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. It was named after the imprisoned German communist leader Ernst Thälmann (born 16 April 1886, executed 18 August 1944) and included approximately 1 ...

, including Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

's nephew, Esmond Romilly

}

Esmond Marcus David Romilly (10 June 1918 – 30 November 1941) was a British socialist, anti-fascist, and journalist, who was in turn a schoolboy rebel, a veteran with the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War and, following th ...

. Notable anti-fascists who worked internationally against Franco included: George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950) was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to a ...

(who fought in the POUM militia and wrote ''Homage to Catalonia

''Homage to Catalonia'' is a 1938 memoir by English writer George Orwell, in which he accounts his personal experiences and observations while fighting in the Spanish Civil War.

Covering the period between December 1936 and June 1937, Orwell re ...

'' about his experience), Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized fo ...

(a supporter of the International Brigades who wrote ''For Whom the Bell Tolls

''For Whom the Bell Tolls'' is a novel by Ernest Hemingway published in 1940. It tells the story of Robert Jordan, a young American volunteer attached to a Republican guerrilla unit during the Spanish Civil War. As a dynamiter, he is assigned ...

'' about his experience), and the radical journalist Martha Gellhorn

Martha Ellis Gellhorn (8 November 1908 – 15 February 1998) was an American novelist, travel writer and journalist who is considered one of the great war correspondents of the 20th century. She reported on virtually every major world confli ...

.

The Spanish anarchist guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

Francesc Sabaté Llopart Francesc () is a masculine given name of Catalan origin. It is a cognate of Francis, Francesco, Francisco, François, and Franz. People with the name include:

* Cesc Fàbregas (Francesc Fàbregas i Soler) (born 1987), Spanish professional footbal ...

fought against Franco's regime until the 1960s, from a base in France. The Spanish Maquis

The Maquis (; ; also spelled maqui) were Spanish guerrillas who waged irregular warfare against the Francoist dictatorship within Spain following the Republican defeat in the Spanish Civil War until the early 1960s, carrying out sabotage, rob ...

, linked to the PCE, also fought the Franco regime long after the Spanish Civil war had ended.

France: against ''Action Française'' and Vichy

In the 1920s and 1930s in the

In the 1920s and 1930s in the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

, anti-fascists confronted aggressive far-right

Far-right politics, often termed right-wing extremism, encompasses a range of ideologies that are marked by ultraconservatism, authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and nativism. This political spectrum situates itself on the far end of the ...

groups such as the Action Française

''Action Française'' (, AF; ) is a French far-right monarchist and nationalist political movement. The name was also given to a journal associated with the movement, '' L'Action Française'', sold by its own youth organization, the Camelot ...

movement in France, which dominated the Latin Quarter

The Latin Quarter of Paris (, ) is an urban university campus in the 5th and the 6th arrondissements of Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine, around the Sorbonne.

Known for its student life, lively atmosphere, and bistros, t ...

students' neighborhood. After fascism triumphed via invasion, the French Resistance () or, more accurately, resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized group of people that tries to resist or try to overthrow a government or an occupying power, causing disruption and unrest in civil order and stability. Such a movement may seek to achieve its goals through ei ...

s fought against the Nazi German

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

occupation and against the collaborationist Vichy régime. Resistance cells were small groups of armed men and women (called the ''maquis'' in rural areas), who, in addition to their guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

activities, were also publishers of underground newspapers and magazines such as '' Arbeiter und Soldat'' (''Worker and Soldier'') during World War Two, providers of first-hand intelligence information, and maintainers of escape networks.

United Kingdom: against Mosley's BUF

The rise ofOswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980), was a British aristocrat and politician who rose to fame during the 1920s and 1930s when he, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, turned to fascism. ...

's British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

(BUF) in the 1930s was challenged by the Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

, socialists

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes the economic, political, and socia ...

in the Labour Party and Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberal Party (UK), Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse work ...

, anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state w ...

, Irish Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

dockmen and working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

s in London's East End. A high point in the struggle was the Battle of Cable Street

The Battle of Cable Street was a series of clashes that took place at several locations in the East End of London, most notably Cable Street, on Sunday 4 October 1936. It was a clash between the Metropolitan Police, sent to protect a march ...

, when thousands of local residents and others turned out to stop the BUF from marching. Initially, the national Communist Party leadership wanted a mass demonstration at Hyde Park in solidarity with Republican Spain

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of democratic government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931 after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII. It was dissol ...

, instead of a mobilization against the BUF, but local party activists argued against this. Activists rallied support with the slogan ''They shall not pass

"They shall not pass" ( and ; ; ) is a slogan, notably used by France in World War I, to express a determination to defend a position against an enemy. Its Spanish-language form was also used as an anti-fascist slogan during the Spanish Civil War ...

,'' adopted from Republican Spain.

There were debates within the anti-fascist movement over tactics. While many East End ex-servicemen participated in violence against fascists, Communist Party leader Phil Piratin

Philip Piratin (15 May 1907 – 10 December 1995) was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and one of the four CPGB Members of Parliament during the first thirty years of its existence. (The others were Shapurji Saklatvala, ...

denounced these tactics and instead called for large demonstrations. In addition to the militant anti-fascist movement, there was a smaller current of liberal anti-fascism in Britain; Sir Ernest Barker

Sir Ernest Barker (23 September 1874 – 17 February 1960) was an English political scientist who served as Principal of King's College London from 1920 to 1927.

Life and career

Ernest Barker was born in Woodley, Cheshire, and educated at Ma ...

, for example, was a notable English liberal anti-fascist in the 1930s.

United States, World War II

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the