Annie Chapman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Annie Chapman (born Eliza Ann Smith; 25 September 1840 – 8 September 1888) was the second

On 1 May 1869, Annie married John James Chapman, who was related to her mother.Begg, ''Jack the Ripper: The Facts'', p. 65 The ceremony was conducted at All Saints Church in the Knightsbridge district of London, and was witnessed by one of her sisters, Emily Laticia, and a colleague of her husband named George White.'Annie Chapman: Jack the Ripper Victim A Short Biography'. Written and published by Neal Shelden (2001) The Chapmans' residence on their marriage certificate is listed as 29 Montpelier Place, Brompton, although the couple are believed to have briefly resided with White and his wife in

On 1 May 1869, Annie married John James Chapman, who was related to her mother.Begg, ''Jack the Ripper: The Facts'', p. 65 The ceremony was conducted at All Saints Church in the Knightsbridge district of London, and was witnessed by one of her sisters, Emily Laticia, and a colleague of her husband named George White.'Annie Chapman: Jack the Ripper Victim A Short Biography'. Written and published by Neal Shelden (2001) The Chapmans' residence on their marriage certificate is listed as 29 Montpelier Place, Brompton, although the couple are believed to have briefly resided with White and his wife in

In 1881, the Chapman family relocated from West London to Windsor, where John Chapman took a job as a coachman to a farm bailiff named Josiah Weeks, and the Chapman family living in the attic rooms of St. Leonard Hill Farm Cottage. The following year, Emily Ruth Chapman died of

In 1881, the Chapman family relocated from West London to Windsor, where John Chapman took a job as a coachman to a farm bailiff named Josiah Weeks, and the Chapman family living in the attic rooms of St. Leonard Hill Farm Cottage. The following year, Emily Ruth Chapman died of

Annie Chapman's mutilated body was discovered shortly before 6:00 a.m. by an elderly resident of 29 Hanbury Street named John Davis. Davis noticed that the front door was now open, while the back door was shut. Her body was lying on the ground near the doorway to the back yard, with her head six inches (15 cm) from the steps to the property.Eddleston, ''Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia'', p. 255 Davis alerted three men named James Green, James Kent, and Henry Holland to his discovery, before all three ran down Commercial Street to find a policeman as Davis reported his discovery at the nearest police station.

At the corner of Hanbury Street, Green, Kent, and Holland found Divisional Inspector Joseph Luniss Chandler and told him, "Another woman has been murdered!" Chandler followed the men to Chapman's body before requesting the assistance of police surgeon Dr

Annie Chapman's mutilated body was discovered shortly before 6:00 a.m. by an elderly resident of 29 Hanbury Street named John Davis. Davis noticed that the front door was now open, while the back door was shut. Her body was lying on the ground near the doorway to the back yard, with her head six inches (15 cm) from the steps to the property.Eddleston, ''Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia'', p. 255 Davis alerted three men named James Green, James Kent, and Henry Holland to his discovery, before all three ran down Commercial Street to find a policeman as Davis reported his discovery at the nearest police station.

At the corner of Hanbury Street, Green, Kent, and Holland found Divisional Inspector Joseph Luniss Chandler and told him, "Another woman has been murdered!" Chandler followed the men to Chapman's body before requesting the assistance of police surgeon Dr

Chapman's throat had been cut from left to right so deeply the bones of her

Chapman's throat had been cut from left to right so deeply the bones of her

A leather apron belonging to John Richardson lay under a tap in the yard of 29 Hanbury Street. This apron had been placed there by his mother, who had washed it on 6 September. Richardson was investigated thoroughly by the police, but was eliminated from the enquiry. Nonetheless, press reports of the discovery of this apron fuelled local rumours which had first been published in '' The Star'' on 4 September following the murder of Mary Ann Nichols that a

A leather apron belonging to John Richardson lay under a tap in the yard of 29 Hanbury Street. This apron had been placed there by his mother, who had washed it on 6 September. Richardson was investigated thoroughly by the police, but was eliminated from the enquiry. Nonetheless, press reports of the discovery of this apron fuelled local rumours which had first been published in '' The Star'' on 4 September following the murder of Mary Ann Nichols that a

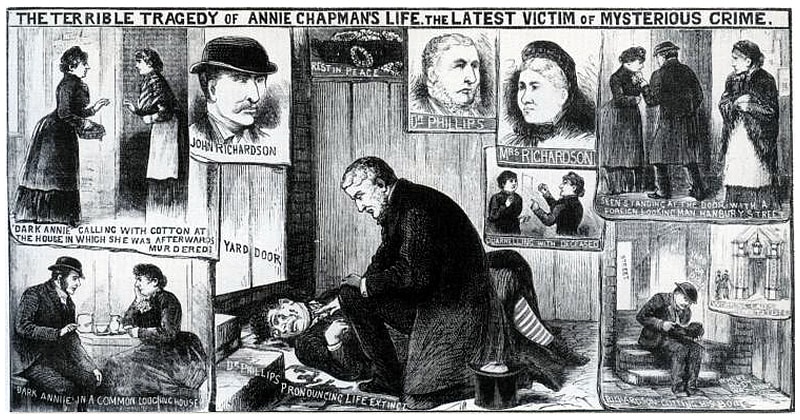

''Contemporary news article''

pertaining to the murder of Annie Chapman *

murders committed by Jack the Ripper

* The Whitechapel Murder Victims: Annie Chapman a

whitechapeljack.com

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chapman, Annie 1840 births 1888 deaths People murdered in 1888 19th-century English women English female prostitutes English murder victims Female murder victims Jack the Ripper victims People from Paddington Women of the Victorian era

canonical

The adjective canonical is applied in many contexts to mean 'according to the canon' the standard, rule or primary source that is accepted as authoritative for the body of knowledge or literature in that context. In mathematics, ''canonical exampl ...

victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer

A serial killer (also called a serial murderer) is a person who murders three or more people,An offender can be anyone:

*

*

*

*

* (This source only requires two people) with the killings taking place over a significant period of time in separat ...

Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer who was active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer was also ...

, who killed and mutilated

Mutilation or maiming (from the ) is severe damage to the body that has a subsequent harmful effect on an individual's quality of life.

In the modern era, the term has an overwhelmingly negative connotation, referring to alterations that rend ...

a minimum of five women in the Whitechapel

Whitechapel () is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. It is the location of Tower Hamlets Town Hall and therefore the borough tow ...

and Spitalfields

Spitalfields () is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in East London and situated in the East End of London, East End. Spitalfields is formed around Commercial Street, London, Commercial Stre ...

districts of London from late August to early November 1888.

Although previous murders linked to Jack the Ripper (then known as the " Whitechapel murderer") had received considerable press and public attention, the murder of Annie Chapman generated a state of panic in the East End of London, with police under increasing pressure to apprehend the culprit.

Early life

Annie Chapman was born Eliza Ann Smith inPaddington

Paddington is an area in the City of Westminster, in central London, England. A medieval parish then a metropolitan borough of the County of London, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Paddington station, designed b ...

on 25 September 1840. She was the first of five children born to George Smith, and Ruth Chapman. George Smith was a soldier, having enlisted in the 2nd Regiment of Life Guards

The 2nd Regiment of Life Guards was a cavalry regiment in the British Army, part of the Household Cavalry. It was formed in 1788 by the union of the 2nd Troop of Horse Guards and 2nd Troop of Horse Grenadier Guards. In 1922, it was amalgamate ...

in December 1834. Reportedly, the location of Chapman's earliest years revolved around her father's military service in London and Windsor

Windsor may refer to:

Places

*Detroit–Windsor, Michigan-Ontario, USA-Canada, North America; a cross-border metropolitan region

Australia New South Wales

*Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area Queen ...

.Rumbelow, ''The Complete Jack the Ripper: Fully Revised and Updated'', p. 39

Chapman's parents were not married at the time of her birth, although they married on 22 February 1842, in Paddington. Following the birth of their second child in 1844, the family relocated to Knightsbridge

Knightsbridge is a residential and retail district in central London, south of Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park. It is identified in the London Plan as one of two international retail centres in London, alongside the West End of London, West End. ...

, where George Smith became a valet

A valet or varlet is a male servant who serves as personal attendant to his employer. In the Middle Ages and Ancien Régime, ''valet de chambre'' was a role for junior courtiers and specialists such as artists in a royal court, but the term "va ...

. The family eventually relocated to Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

in 1856.

According to her brother, Fountain, Annie had "first took a drink when she was quite young", quickly developing a weakness for alcohol, and although both he and two of his other sisters had persuaded her to sign a pledge

Pledge may refer to:

Promises

* a solemn promise

* Abstinence pledge, a commitment to practice abstinence, usually teetotalism or chastity

* The Pledge (New Hampshire), a promise about taxes by New Hampshire politicians

* Pledge of Allegianc ...

to refrain from consuming alcohol, she "was tempted and fell" despite the "over and over" efforts of her siblings to dissuade her.

Family relocation

Census

A census (from Latin ''censere'', 'to assess') is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording, and calculating population information about the members of a given Statistical population, population, usually displayed in the form of stati ...

records from 1861 indicate all members of the Smith family—except Annie—had relocated to the parish of Clewer

Clewer (also known as Clewer Village) is an ecclesiastical parish and an area of Windsor, in the ceremonial county of Berkshire, England. Clewer makes up three wards of the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead, namely Clewer North, Cle ...

. Chapman is believed to have remained in London, possibly due to her employment commitments as a domestic servant. Her father, George Smith (also known as William Smith), was the valet to Captain Thomas Naylor Leland of the Denbighshire Yeomanry Cavalry. On 13 June 1863, Smith accompanied his employer to a horse racing event. He lodged with his employer that evening at the Elephant and Castle

Elephant and Castle is an area of South London, England, in the London Borough of Southwark. The name also informally refers to much of Walworth and Newington, due to the proximity of the London Underground station of the same name. The n ...

, Wrexham

Wrexham ( ; ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in the North East Wales, north-east of Wales. It lies between the Cambrian Mountains, Welsh mountains and the lower River Dee, Wales, Dee Valley, near the England–Wales border, borde ...

. That night, George Smith committed suicide by cutting his throat.

Contemporary accounts describe Annie Chapman as an intelligent and sociable woman with a weakness for alcohol—particularly rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is often aged in barrels of oak. Rum originated in the Caribbean in the 17th century, but today it is produced i ...

. An acquaintance described Chapman at the inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a cor ...

into her murder as being "very civil and industrious when sober

Sober usually refers to sobriety, the state of not having any measurable levels or effects from alcohol or drugs.

Sober may also refer to:

Music

* Sôber, Spanish rock band

Songs

* "Sober" (Bad Wolves song), from the 2019 album ''Nation''

* " ...

", before noting: "I have often seen her the worse for drink." She was in height and had blue eyes and wavy, dark brown hair, leading acquaintances to give her the nickname "Dark Annie".

Marriage

On 1 May 1869, Annie married John James Chapman, who was related to her mother.Begg, ''Jack the Ripper: The Facts'', p. 65 The ceremony was conducted at All Saints Church in the Knightsbridge district of London, and was witnessed by one of her sisters, Emily Laticia, and a colleague of her husband named George White.'Annie Chapman: Jack the Ripper Victim A Short Biography'. Written and published by Neal Shelden (2001) The Chapmans' residence on their marriage certificate is listed as 29 Montpelier Place, Brompton, although the couple are believed to have briefly resided with White and his wife in

On 1 May 1869, Annie married John James Chapman, who was related to her mother.Begg, ''Jack the Ripper: The Facts'', p. 65 The ceremony was conducted at All Saints Church in the Knightsbridge district of London, and was witnessed by one of her sisters, Emily Laticia, and a colleague of her husband named George White.'Annie Chapman: Jack the Ripper Victim A Short Biography'. Written and published by Neal Shelden (2001) The Chapmans' residence on their marriage certificate is listed as 29 Montpelier Place, Brompton, although the couple are believed to have briefly resided with White and his wife in Bayswater

Bayswater is an area in the City of Westminster in West London. It is a built-up district with a population density of 17,500 per square kilometre, and is located between Kensington Gardens to the south, Paddington to the north-east, and ...

.

In the years following their marriage, the Chapmans lived at various West London

West London is the western part of London, England, north of the River Thames, west of the City of London, and extending to the Greater London boundary.

The term is used to differentiate the area from the other parts of London: Central London, N ...

addresses. In the early 1870s, John Chapman obtained employment in the service of a nobleman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

in Bond Street

Bond Street in the West End of London links Piccadilly in the south to Oxford Street in the north. Since the 18th century the street has housed many prestigious and upmarket fashion retailers. The southern section is Old Bond Street and the l ...

.Begg, ''Jack the Ripper: The Facts'', p. 66

Children

The couple had three children: Emily Ruth (b. 25 June 1870); Annie Georgina (b. 5 June 1873); and John Alfred (b. 21 November 1880). Emily Ruth was born at Chapman's mother's home in Montpelier Place, Knightsbridge; Annie Georgina was born at South Bruton Mews,Mayfair

Mayfair is an area of Westminster, London, England, in the City of Westminster. It is in Central London and part of the West End. It is between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane and one of the most expensive districts ...

; and John Alfred was born in the Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

village of Bray

Bray may refer to:

Places France

* Bray, Eure, in the Eure ''département''

* Bray, Saône-et-Loire, in the Saône-et-Loire ''département''

* Bray-Dunes, in the Nord ''département''

* Bray-en-Val, in the Loiret ''département''

* Bray-et-Lû ...

. John was born cripple

A cripple is a person or animal with a physical disability, particularly one who is unable to walk because of an injury or illness. The word was recorded as early as 950 AD, and derives from the Proto-Germanic ''krupilaz''. The German and Dutc ...

d. The Chapmans sought medical help for their son John at a London hospital before later placing him in the care of an institution for the physically disabled close to Windsor.

Although Chapman had struggled with alcoholism

Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World He ...

as an adult, she had reportedly weaned herself off drink by 1880. Her son's disability is believed to have contributed to her gradual reversion to alcohol dependency

Alcohol dependence is a previous (DSM-IV and ICD-10) psychiatric diagnosis in which an individual is physically or psychologically dependent upon alcohol (also chemically known as ethanol).

In 2013, it was reclassified as alcohol use disorder ...

.Gray, ''London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City'', p. 163

In 1881, the Chapman family relocated from West London to Windsor, where John Chapman took a job as a coachman to a farm bailiff named Josiah Weeks, and the Chapman family living in the attic rooms of St. Leonard Hill Farm Cottage. The following year, Emily Ruth Chapman died of

In 1881, the Chapman family relocated from West London to Windsor, where John Chapman took a job as a coachman to a farm bailiff named Josiah Weeks, and the Chapman family living in the attic rooms of St. Leonard Hill Farm Cottage. The following year, Emily Ruth Chapman died of meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, intense headache, vomiting and neck stiffness and occasion ...

on her brother's second birthday at the age of 12.

Following the death of their daughter, both Chapman and her husband took to heavy drinking. Over the following years, she is known to have been arrested on several occasions for public intoxication

Public intoxication, also known as "drunk and disorderly" and "drunk in public", is a summary offense in certain countries related to public cases or displays of drunkenness. Public intoxication laws vary widely by jurisdiction, but usually requ ...

in both Clewer and Windsor, though no records exist of her ever being brought before a magistrates court

A magistrates' court is a lower court where, in several jurisdictions, all criminal proceedings start. Also some civil matters may be dealt with here, such as family proceedings.

Courts

* Magistrates' court (England and Wales)

* Magistrates' court ...

for these arrests.

Separation

Chapman and her husband separated by mutual consent in 1884. John Chapman retained custody of their surviving daughter, while Annie relocated to London. Her husband was obliged to pay her a weekly allowance of 10shillings

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence ...

via Post Office Order. The precise reason for the couple's separation is unknown, although a later police report lists the reason for their separation as Annie Chapman's "drunken and immoral

Immorality is the violation of moral laws, norms or standards. It refers to an agent doing or thinking something they know or believe to be wrong. Immorality is normally applied to people or actions, or in a broader sense, it can be applied to gr ...

ways".

Two years later, in 1886, John Chapman resigned from his job due to his declining health and relocated to New Windsor. He died of liver cirrhosis

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, chronic liver failure or chronic hepatic failure and end-stage liver disease, is a chronic condition of the liver in which the normal functioning tissue, or parenchyma, is replaced ...

and edema

Edema (American English), also spelled oedema (British English), and also known as fluid retention, swelling, dropsy and hydropsy, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue (biology), tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. S ...

, on 25 December, leading to the cessation of these weekly payments.''Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History'' p. 188 Chapman learned of her husband's death through her brother-in-law. Her surviving daughter, Annie Georgina (then aged 13), is believed to have either subsequently been placed in a French institution or to have joined a performing troupe which travelled with a circus in France. Census records from 1891 reveal both of Chapman's surviving children lived with their grandmother in Knightsbridge.

Life in Whitechapel

Following her separation from her husband, Annie Chapman relocated to Whitechapel, primarily living upon the weekly allowance of 10 s from her husband. Over the following years, she resided incommon lodging-house

"Common lodging-house" is a Victorian era term for a form of cheap accommodation in which the inhabitants (who are not members of one family) are all lodged together in the same room or rooms, whether for eating or sleeping. The slang terms ''doss ...

s in both Whitechapel and Spitalfields.''Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History'' p. 188 By 1886, she is known to have resided with a man who made wire sieves for a living, consequently becoming known to some acquaintances as "Annie Sievey" or "Siffey". At the end of 1886, her weekly allowance abruptly stopped. Upon enquiring why these weekly payments had suddenly ceased, Chapman discovered her husband had died of alcohol-related causes.Begg, ''Jack the Ripper: The Facts'', p. 70

Shortly after John Chapman's death, this sieve-maker left Chapman—possibly due to the cessation of her allowance—and relocated to Notting Hill

Notting Hill is a district of West London, England, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Notting Hill is known for being a wikt:cosmopolitan, cosmopolitan and multiculturalism, multicultural neighbourhood, hosting the annual Notting ...

. One of Chapman's friends said she became depressed after this separation and seemed to lose her will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

to live.

1888

By May or June 1888, Chapman resided in Crossingham's Lodging House at 35 Dorset Street, paying 8 d a night for a double bed. According to the lodging-house deputy, Timothy Donovan, a 47-year-old bricklayer's labourer named Edward "The Pensioner" Stanley would typically stay with Chapman at the lodging house between Saturday and Monday, occasionally paying for her bed. She earned some income fromcrochet

Crochet (; ) is a process of creating textiles by using a crochet hook to interlock loops of yarn, thread (yarn), thread, or strands of other materials. The name is derived from the French term ''crochet'', which means 'hook'. Hooks can be made ...

work, making antimacassar

An antimacassar is a small cloth placed over the backs or arms of chairs, or the head or cushions of a sofa, to prevent soiling of the permanent fabric underneath.Fleming, John & Hugh Honour. (1977) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Decorative Ar ...

s, and working as a flower seller

upRudolf Ernst painting of The Flower Vendor

A flower seller, traditionally a woman, sells flowers on the street. Often the flowers are carried in a basket, for example. The subject matter has been a favorite of artists.Diego RiveraThe Flower Se ...

, supplemented by casual prostitution.

Eight days prior to Chapman's death, she had fought with a fellow Crossingham's Lodging House resident named Eliza Cooper. The two were reportedly rivals for the affections of a local hawker named Harry, although Cooper later claimed the reason the two had fought had been because Chapman had borrowed a bar of soap from her, and after being asked to return it, Chapman had simply thrown a halfpenny upon a kitchen table, saying, "Go get a halfpenny's worth of soap."Bell, ''Capturing Jack the Ripper: In the Boots of a Bobby in Victorian England'', p. 114 Later, in a fight between the two at the Britannia Public House, Cooper struck Chapman in the face and chest, resulting in her sustaining a black eye and bruised breast.

On 7 September, Amelia Palmer encountered Annie Chapman in Dorset Street. Palmer later informed police Chapman had appeared visibly pale

Pale may refer to:

Jurisdictions

* Medieval areas of English conquest:

** Pale of Calais, in France (1360–1558)

** The Pale, or the English Pale, in Ireland

*Pale of Settlement, area of permitted Jewish settlement, western Russian Empire (179 ...

on this occasion, having been discharged from the casual ward of the Whitechapel Infirmary that day. Chapman complained to Palmer of having felt "too ill to do anything".

After Chapman's death, the coroner who conducted her autopsy noted her lungs and brain membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. Bi ...

s were in an advanced state of disease which would have killed her within months.

8 September

According to both the lodging-house deputy, Timothy Donovan, and the watchman, John Evans, shortly after midnight on 8 September, Chapman had been lacking the required money for her nightly lodging. She drank a pint of beer in the kitchen with fellow lodger Frederick Stevens at approximately 12:10 a.m. before informing another lodger that she had earlier visited her sister inVauxhall

Vauxhall ( , ) is an area of South London, within the London Borough of Lambeth. Named after a medieval manor called Fox Hall, it became well known for the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens.

From the Victorian period until the mid-20th century, Va ...

, and that her family had given her 5 d. Stevens then observed Chapman take a box of pills from her pocket. This box then broke, whereupon Chapman wrapped the pills in a section of envelope she had taken from a mantlepiece before leaving the property. At approximately 1:35 a.m., Chapman returned to the lodging-house with a baked potato which she ate before again leaving the premises with a likely intention of earning the money to pay for a bed via prostituting herself, stating: "I won't be long, Brummie

Brummie is the associated adjective and demonym of Birmingham, a city of West Midlands in England. It may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the city of Birmingham, in particular:

** The people of Birmingham (see also List of people from Bir ...

. See that Tim keeps the bed for me." Evans last saw Chapman walking in the direction of Spitalfields Market Spitalfields Market may refer to:

* Old Spitalfields Market, a covered market in Spitalfields, just outside the City of London

* New Spitalfields Market

New Spitalfields Market is a fruit and vegetable market on a site in Leyton, London Borough ...

.

A Mrs Elizabeth Long testified at the subsequent inquest into Chapman's murder that she had observed Chapman talking with a man at 5:30 a.m. The two had stood just beyond the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street

Hanbury Street is a street running from Commercial Street in Spitalfields to Old Montague Street in Whitechapel located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The eastern section is restricted to pedal cycles and pedestrians only.

History

Th ...

, Spitalfields. Long described this man as being over 40 years old, slightly taller than Chapman, with dark hair, and of a foreign, "shabby-genteel

Gentry (from Old French , from ) are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past. ''Gentry'', in its widest connotation, refers to people of good social position connected to Landed property, landed es ...

" appearance. He was wearing a brown low-crowned felt hat and possibly a dark coat.Begg, p. 153; Cook, p. 163; Evans and Skinner, ''The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook'', p. 98; Marriott, pp. 59–75 According to Long, the man had asked Chapman the question, "Will you?" to which Chapman replied, "Yes."

Long was certain as to Chapman's identity and the time of this sighting, as she had heard the chiming of a nearby clock strike the half-hour just before she had entered Hanbury Street. If she had indeed seen Chapman, she was likely the last person to see her alive, and in the company of her murderer.

Murder

Shortly before 5:00 a.m. on 8 September, the son of a resident of 29 Hanbury Street, John Richardson, entered the back yard of the property to check the padlocked cellar in the yard was still intact and to trim a loose piece of leather from his boot. Richardson verified the cellar was still padlocked, then sat on the rear steps of the property to trim the loose leather from his boot, noting nothing untoward.Fido, p. 31 He then exited the property via the front door approximately three minutes later, having not proceeded beyond the steps to the back yard. At approximately 5:15 a.m., a tenant of 27 Hanbury Street named Albert Cadosch entered the yard of the property to use the lavatory. Cadosch later informed police he had heard a woman say, "No, no!" before hearing the sound of something or someone falling against the fence dividing the back yards of numbers 27 and 29 Hanbury Street. He did not investigate these sounds. Annie Chapman's mutilated body was discovered shortly before 6:00 a.m. by an elderly resident of 29 Hanbury Street named John Davis. Davis noticed that the front door was now open, while the back door was shut. Her body was lying on the ground near the doorway to the back yard, with her head six inches (15 cm) from the steps to the property.Eddleston, ''Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia'', p. 255 Davis alerted three men named James Green, James Kent, and Henry Holland to his discovery, before all three ran down Commercial Street to find a policeman as Davis reported his discovery at the nearest police station.

At the corner of Hanbury Street, Green, Kent, and Holland found Divisional Inspector Joseph Luniss Chandler and told him, "Another woman has been murdered!" Chandler followed the men to Chapman's body before requesting the assistance of police surgeon Dr

Annie Chapman's mutilated body was discovered shortly before 6:00 a.m. by an elderly resident of 29 Hanbury Street named John Davis. Davis noticed that the front door was now open, while the back door was shut. Her body was lying on the ground near the doorway to the back yard, with her head six inches (15 cm) from the steps to the property.Eddleston, ''Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia'', p. 255 Davis alerted three men named James Green, James Kent, and Henry Holland to his discovery, before all three ran down Commercial Street to find a policeman as Davis reported his discovery at the nearest police station.

At the corner of Hanbury Street, Green, Kent, and Holland found Divisional Inspector Joseph Luniss Chandler and told him, "Another woman has been murdered!" Chandler followed the men to Chapman's body before requesting the assistance of police surgeon Dr George Bagster Phillips

George Bagster Phillips (February 1835 in Camberwell, Surrey – 27 October 1897 in London) was, from 1865, the Police Surgeon for the Metropolitan Police, Metropolitan Police's 'H' Division, which covered London, London's Whitechapel distri ...

and more officers. Several policemen arrived within minutes. They were instructed to clear the passageway to the yard to ensure Dr Phillips had access. Phillips arrived at Hanbury Street at approximately 6:30 a.m.

Dr Phillips was quickly able to establish a definite link between Chapman's murder and the murder of Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann Nichols, known as Polly Nichols (née Walker; 26 August 184531 August 1888), was the first Jack the Ripper#Canonical five, canonical victim of the unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have murdered an ...

, which had occurred on 31 August. Nichols had also suffered two deep slash wounds to the throat, inflicted from the left to the right of her neck, before her murderer had mutilated her abdomen, and a blade of similar size and design had been used in both murders. Phillips also observed six areas of blood spattering upon the wall of the house between the steps and wooden palings dividing 27 and 29 Hanbury Street. Some of these spatterings were 18 inches (45 cm) above the ground.

Two pills, which Chapman had been prescribed for a lung condition, a section of a torn envelope, a small piece of frayed coarse muslin

Muslin () is a cotton fabric of plain weave. It is made in a wide range of weights from delicate sheers to coarse sheeting. It is commonly believed that it gets its name from the city of Mosul, Iraq.

Muslin was produced in different regions o ...

, and a comb were recovered close to her body. A leather apron, partially submerged in a dish of water located close to a tap, was also discovered close to her body.

Contemporary press reports also claim that two farthing

Farthing or farthings may refer to:

Coinage

*Farthing (British coin), an old British coin valued one quarter of a penny

** Half farthing (British coin)

** Third farthing (British coin)

** Quarter farthing (British coin)

*Farthing (English c ...

s were also found in the yard of Hanbury Street close to Chapman's body, although no reference is made to these coins in any surviving contemporary police records. The local inspector of the Metropolitan Police Service, Edmund Reid

Detective Inspector Edmund John James Reid (21 March 1846 – 5 December 1917) was the head of the CID in the Metropolitan Police's H Division at the time of the Whitechapel murders of Jack the Ripper in 1888. He was also an early aeronau ...

of H Division Whitechapel, was reported as mentioning these coins at an inquest in 1889, and the acting Commissioner of the City Police, Major Henry Smith, also referenced these coins in his memoir

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based on the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autob ...

s. Smith's memoirs, written more than twenty years after the Whitechapel murders

The Whitechapel murders were committed in or near the impoverished Whitechapel District (Metropolis), Whitechapel district in the East End of London between 3 April 1888 and 13 February 1891. At various points some or all of these eleven unso ...

, are generally considered to be both unreliable and embellished for dramatic effect.

Inquest

The official inquest into Chapman's death was opened at the Working Lad's Institute, Whitechapel, on 10 September. This inquest was presided over by theMiddlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, former county in South East England, now mainly within Greater London. Its boundaries largely followed three rivers: the River Thames, Thames in the south, the River Lea, Le ...

coroner, Wynne Edwin Baxter

Wynne Edwin Baxter FRMS FGS (1 May 1844 – 1 October 1920) was an English lawyer, translator, antiquarian and botanist, but is best known as the coroner who conducted the inquests on most of the victims of the Whitechapel Murders of 1888 to ...

. The first day of the inquest heard testimony from four witnesses, including John Davies, who testified to his discovery of Chapman's body. Davies testified he had lived at Hanbury Street for two weeks and had never seen the door to the yard of the property locked. He added that any individual who knew where the latch to the front door of the property was could open it to facilitate access to the backyard. Also to testify were Timothy Donovan and John Evans, both of whom testified they had positively identified the body of the deceased as Annie Chapman. Donovan also testified he had last seen Chapman alive at approximately 1:50 a.m. on 8 September, and the last words she had spoken to him were: "I have not sufficient money for my bed. Don't let it. I shan't be long before I am in."

Character testimony

Fellow Crossingham's Lodging House resident Amelia Palmer also testified on the first day of the inquest that she had known Chapman for several years, and had been in the habit of writing letters for her. Palmer testified that although Chapman had a fondness for alcohol, she considered her a respectable woman who never used profane language. She also testified Chapman had "not as a regular means of livelihood" been in the habit of selling sexual favours for money, adding she most often earned her income by performing crochet work or purchasing matches and flowers to sell for a small profit and had only begun resorting to prostitution following the death of her husband in December 1886. Every Friday, Chapman would travel to Stratford to "sell anything she had". The lodging-house deputy, Timothy Donovan, testified Chapman had always been on good terms with other lodgers, with the quarrel and resulting fisticuffs between herself and Eliza Cooper on 31 August being the only incident of trouble at the premises involving her. Donovan also testified that although Chapman would typically drink to excess on Saturday nights, she was most often sober for the remainder of the week.Medical testimony

The third day of the inquest saw testimony from police called to the crime scene and the subsequent post-mortem. This medical testimony indicated that Chapman may have been murdered as late as 5:30 a.m. in the yard of Hanbury Street. Previous testimony from several tenants of 29 Hanbury Street had revealed none had seen or heard anything suspicious at the time of Chapman's murder, with John Richardson testifying on the second day of the inquest that the passageway through the house to the back-yard was not locked, as it was frequented by residents at all hours of the day, and that the front door had been wide open at the time Chapman's body was discovered. Richardson also testified he had often seen strangers, both men and women, loitering in the passageway of the house. On 13 September, Dr George Bagster Phillips described the body as he observed it at 6:30 a.m. in the back yard of the house at 29 Hanbury Street: Chapman's throat had been cut from left to right so deeply the bones of her

Chapman's throat had been cut from left to right so deeply the bones of her vertebral column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmente ...

bore striations, and she had been disembowelled

Disembowelment, disemboweling, evisceration, eviscerating or gutting is the removal of organs from the gastrointestinal tract (bowels or viscera), usually through an incision made across the abdominal area. Disembowelment is a standard routine ...

, with a section of the flesh from her stomach being placed upon her left shoulder and another section of skin and flesh—plus her small intestine

The small intestine or small bowel is an organ (anatomy), organ in the human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract where most of the #Absorption, absorption of nutrients from food takes place. It lies between the stomach and large intes ...

s—being removed and placed above her right shoulder. The morgue examination revealed that part of her uterus

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', : uteri or uteruses) or womb () is the hollow organ, organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans, that accommodates the embryonic development, embryonic and prenatal development, f ...

and bladder was missing. Chapman's protruding tongue and swollen face led Dr Phillips to believe that she may have been asphyxiated

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects all the tissues and organs, some more rapidly than others. There are m ...

with the handkerchief around her neck before her throat was cut, and that her murderer had held her chin as he performed this act. As there was no blood trail leading to the yard, he was certain that she was killed where she was found.

Phillips concluded that Chapman suffered from a long-standing lung disease, that she was sober at the time of her death, and that she had not consumed alcoholic beverages for at least some hours before death. He was of the opinion that the murderer must have possessed anatomical knowledge to have sliced out her reproductive organs in a single movement with a blade about 6–8 inches (15–20 cm) long. However, the idea that the murderer possessed surgical skill was dismissed by other experts. As her body was not examined extensively at the scene, it has also been suggested that the organ was removed by mortuary staff, who took advantage of bodies that had already been opened to extract organs that they could then sell as surgical specimens. In his summing up, Coroner Baxter raised the possibility that Chapman was murdered deliberately to obtain the uterus, on the basis that an American had made enquiries at a London medical school for the purchase of such organs. ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal, founded in England in 1823. It is one of the world's highest-impact academic journals and also one of the oldest medical journals still in publication.

The journal publishes ...

'' rejected Baxter's suggestion, scathingly pointing out "certain improbabilities and absurdities", and saying it was "a grave error of judgement". The ''British Medical Journal

''The BMJ'' is a fortnightly peer-reviewed medical journal, published by BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, which in turn is wholly-owned by the British Medical Association (BMA). ''The BMJ'' has editorial freedom from the BMA. It is one of the world ...

'' was similarly dismissive, and reported that the physician who requested the samples was a highly reputable doctor, unnamed, who had left the country 18 months before the murder. Baxter dropped the theory and never referred to it again. The ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is an American daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1847, it was formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper", a slogan from which its once integrated WGN (AM), WGN radio and ...

'' claimed the American doctor was from Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, and author Philip Sugden later speculated that the man in question was the notorious Francis Tumblety.

Discussing Chapman's time of death, Dr Phillips estimated that she had died either at or before 4:30 a.m., contradicting the inquest eyewitnesses Richardson, Long and Cadosch, all of whom indicated Chapman's murder had occurred after this time. However, Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literatur ...

methods of estimating the time of death of an individual, such as measuring body temperature

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

, were crude by modern methodology. Phillips himself highlighted at the inquest that Chapman's body temperature could have cooled more quickly than normally expected.

Conclusion

The inquest into Chapman's murder lasted five days, with the final day of hearings beingadjourned

In parliamentary procedure, an adjournment ends a meeting. It could be done using a motion to adjourn. A time for another meeting could be set using the motion to fix the time to which to adjourn.

Law

In law, to adjourn means to suspend or postp ...

until 26 September. No further witnesses testified on this date, although coroner Baxter informed the jury: "I have no doubt that if the perpetrator of this foul murder is eventually discovered, our efforts will not have been useless."

Following a short deliberation, the jury, having been instructed to consider precisely how, when, and by what means Chapman came about her death, returned a verdict of wilful murder against a person or persons unknown.

Investigation

On 15 September, Chief InspectorDonald Swanson

Chief Inspector Donald Sutherland Swanson (12 August 1848 - 24 November 1924) was a senior police officer in the Metropolitan Police in London during the notorious Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.

Early life

The son of John Swanson, a brewer, ...

of Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's London boroughs, 32 boroughs. Its name derives from the location of the original ...

was placed in overall command of the investigation into Chapman's murder. Swanson later reported that an "immediate and searching enquiry was made at all common lodging-houses to ascertain if anyone had entered heir premiseson the morning with blood on his hands or clothes, or under any suspicious circumstances".

Leather Apron

A leather apron belonging to John Richardson lay under a tap in the yard of 29 Hanbury Street. This apron had been placed there by his mother, who had washed it on 6 September. Richardson was investigated thoroughly by the police, but was eliminated from the enquiry. Nonetheless, press reports of the discovery of this apron fuelled local rumours which had first been published in '' The Star'' on 4 September following the murder of Mary Ann Nichols that a

A leather apron belonging to John Richardson lay under a tap in the yard of 29 Hanbury Street. This apron had been placed there by his mother, who had washed it on 6 September. Richardson was investigated thoroughly by the police, but was eliminated from the enquiry. Nonetheless, press reports of the discovery of this apron fuelled local rumours which had first been published in '' The Star'' on 4 September following the murder of Mary Ann Nichols that a Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

from the district known as "Leather Apron" was responsible for the Whitechapel murders.

Journalists, frustrated by the general unwillingness of the Criminal Investigation Department

The Criminal Investigation Department (CID) is the branch of a police force to which most plainclothes criminal investigation, detectives belong in the United Kingdom and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth nations. A force's CID is disti ...

to reveal many details of their investigation to the public, and eager to capitalise on the increasing public unrest regarding the Whitechapel murders, frequently resorted to writing reports of questionable veracity. Imaginative descriptions of "Leather Apron", using crude Jewish stereotypes, appeared in the press. The ''Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' reported that: "Whatever information may be in the possession of the police they deem it necessary to keep secret ... It is believed their attention is particularly directed to ... a notorious character known as 'Leather Apron'." Rival journalists dismissed these accounts as "a myth

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

ical outgrowth of the reporter's fancy".

John Pizer

John Pizer (21 September 1850 – 7 July 1897) was an English bootmaker in Whitechapel, London. He was the first person accused of being the perpetrator in the Whitechapel murders, but was cleared of suspicion after providing alibis for the two ...

, a 38-year-old Polish Jew who made footwear from leather, was known by the name "Leather Apron". Via knifepoint, Pizer frequently intimidated

Intimidation is a behaviour and legal wrong which usually involves deterring or coercing an individual by threat of violence. It is in various jurisdictions a crime and a civil wrong (tort). Intimidation is similar to menacing, coercion, terrori ...

local prostitutes.Marriott, p. 251 He appeared before the Thames Magistrates' Court on 4 August 1888, charged with indecent assault

Indecent assault is an offence of aggravated assault in some common law-based jurisdictions. It is characterised as a sex crime and has significant overlap with offences referred to as sexual assault.

England and Wales

Indecent assault was a broa ...

. Pizer is also believed to have stabbed a man in the hand in 1887.

Despite there being no direct evidence

In law, a body of facts that directly supports the truth of an assertion without intervening inference. It is often exemplified by eyewitness testimony, which consists of a witness's description of their reputed direct sensory experience of an ...

against Pizer, he was arrested by a Sergeant William Thicke on 10 September. Although Pizer claimed to the contrary, Thicke knew of Pizer's local reputation, and his "Leather Apron" nick-name.

Pizer was released from custody on 11 September after police were able to verify his alibis on the nights of the murders of both Chapman and Nichols. He was called as a witness on the second day of the inquest into Chapman's murder to publicly clear his name, and demolish the public suspicions that he was the killer. Pizer also successfully obtained monetary compensation from at least one newspaper that had published several articles naming him as the prime suspect in the Whitechapel murders.

Pawnbrokers

Two brass rings—one flat; one oval—Chapman is known to have worn were not recovered at the crime scene, either because she had pawned them or because they had been stolen, possibly by her murderer. Theorising her murderer had removed these items of jewellery in order to pawn them, police unsuccessfully searched all the pawnbrokers in Spitalfields and Whitechapel.Evans and Rumbelow, p. 69Edward Stanley

The section of a torn envelope recovered close to Chapman's body, bearing the crest of theRoyal Sussex Regiment

The Royal Sussex Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army that was in existence from 1881 to 1966. The regiment was formed in 1881 as part of the Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 35th (Royal Sussex) Regiment of Foo ...

and postmarked 'London, 28 August 1888', was briefly believed could be traced to Edward Stanley, thus placing him at the scene of Chapman's murder. Stanley was soon eliminated as a suspect as his alibis for the nights of the murders of both Nichols and Chapman were quickly confirmed. Between 6 August and 1 September, he was known to have been on active duty with the Hampshire Militia in Gosport

Gosport ( ) is a town and non-metropolitan district with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in Hampshire, England. At the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 Census, the town had a population of 70,131 and the district had a pop ...

, and on the night of Chapman's murder, eyewitnesses confirmed Stanley had been at his lodgings.

Further enquiries and arrests

In addition to John Pizer and Edward Stanley, police investigated and/or detained several other individuals in their investigation into Chapman's murder, all of whom were released from custody. On 9 September, a 53-year-old ship's cook named William Henry Piggott was detained after arriving at aGravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames, opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Roche ...

pub with a recent hand injury and shouting misogynistic

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women or girls. It is a form of sexism that can keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the social roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been widely practis ...

remarks. A blood-stained shirt he had left in a local fish shop was quickly traced to Piggott, who claimed that he had been bitten by a woman and that the blood on the shirt was his own. He was investigated, but soon released from custody.

A Swiss butcher, Jacob Isenschmid, matched an eyewitness description of a blood-stained man seen acting suspiciously on the morning of Chapman's murder by a public house landlady, a Mrs Fiddymont. Isenschmid's distinctive appearance included a large ginger moustache, and he was known to have had a history of mental illness. He was arrested on suspicion of committing Chapman's murder on 13 September.

On 18 September, a 40-year-old German hairdresser named Charles Ludwig was arrested after he attempted to stab a young man named Alexander Finlay at a coffee stall while intoxicated. Ludwig was arrested very shortly after this incident in the company of a visibly distressed prostitute, who later informed a policeman: "Dear me! He frightened me very much when he pulled a big knife out." Ludwig was also known to have been wanted by the City of London Police

The City of London Police is the territorial police force#United Kingdom, territorial police force responsible for law enforcement within the City of London, England, including the Middle Temple, Middle and Inner Temple, Inner Temples.

The for ...

for attempting to slash a woman's throat with a razor.

Isenschmid and Ludwig were both ultimately cleared of suspicion after two further murders were committed on the same date while both were in police custody. Isenschmid was later detained in a mental asylum. Other suspects named in contemporary police records and newspapers pertaining to the investigation into Chapman's murder include a local trader named Friedrich Schumacher, pedlar Edward McKenna, apothecary

''Apothecary'' () is an Early Modern English, archaic English term for a medicine, medical professional who formulates and dispenses ''materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons and patients. The modern terms ''pharmacist'' and, in Brit ...

and mental patient Oswald Puckridge, and insane medical student John Sanders. No evidence exists against any of these individuals.

Media moniker

On 27 September, the Central News Agency received the "Dear Boss" letter, written by an individual claiming to be the murderer. The author of this letter paid reference to the press naming him as "Leather Apron", stating: "That joke about Leather Apron gave me fits". The author concluded this letter with the words "Yours truly, Jack the Ripper". This name quickly supplanted "Leather Apron" as the media's favourite moniker for the murderer.

Funeral

Chapman's body was moved from Hanbury Street to a mortuary in Montagu Street, Marylebone by Sergeant Edward Badham in a handcart large enough to hold one coffin. This was similar to the cart previously used to move the body of Mary Ann Nichols. Chapman was buried shortly after 9:00 a.m. on 14 September 1888 in a service paid for by her family. She was laid to rest in a communal grave within Manor Park Cemetery,Forest Gate

Forest Gate is a district of West Ham in the London Borough of Newham, East London, England. It is located northeast of Charing Cross.

The area's name relates to its position adjacent to Wanstead Flats, the southernmost part of Epping Forest. ...

, east London. At the request of Chapman's family, the funeral was not publicised, with no mourning coaches

Coach may refer to:

Guidance/instruction

* Coach (sport), a director of Athletes' training and activities

* Coaching, the practice of guiding an individual through a process

** Acting coach, a teacher who trains performers

Transportation

* Coac ...

used throughout the service, and only the undertaker

A funeral director, also known as an undertaker or mortician (American English), is a professional who has licenses in funeral arranging and embalming (or preparation of the deceased) involved in the business of funeral rites. These tasks o ...

, police, and her relatives knowing of these arrangements. Consequently, relatives and a small number of friends were the only people to attend the service.

A hearse supplied by Hanbury Street undertaker Henry Smith travelled to the Whitechapel Mortuary in Montague Street to collect Chapman's body at 7:00 a.m. Her body was placed in an elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the genus ''Ulmus'' in the family Ulmaceae. They are distributed over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical- montane regions of North America and Eurasia, ...

coffin draped in black and was then driven to Spitalfields undertaker Harry Hawes, who arranged the funeral. By prearrangement, Chapman's relatives and friends met the hearse outside the cemetery. Chapman was buried in communal grave 78, square 148. Her coffin plate bore the words "Annie Chapman, died Sept. 8, 1888, aged 48 years."

The precise location of Annie Chapman's grave within Manor Park Cemetery is now unknown. A plaque placed in the cemetery by authorities in 2008 reads: "Her remains are buried within this area." A headstone was later erected close to this plaque.

Media

Film

* ''A Study in Terror

A, or a, is the first letter and the first vowel letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, and others worldwide. Its name in English is '' a'' (pronounced ), plural ''aes''.

It is similar in shape to the Ancient ...

'' (1965). This film casts Barbara Windsor

Dame Barbara Windsor (born Barbara Ann Deeks; 6 August 193710 December 2020) was an English actress, known for her roles in the Carry On (franchise), ''Carry On'' films and for playing Peggy Mitchell in the BBC One soap opera ''EastEnders''.

as Annie Chapman.

* '' Love Lies Bleeding'' (1999). A drama film

In film and television, drama is a category or genre of narrative fiction (or semi-fiction) intended to be more serious than humorous in tone. The drama of this kind is usually qualified with additional terms that specify its particular ...

directed by William Tannen. Chapman is portrayed by Michaela Hans.

* ''From Hell

''From Hell'' is a graphic novel by writer Alan Moore and artist Eddie Campbell, originally published in serial form from 1989 to 1998. The full collection was published in 1999 by Top Shelf Productions.

Set during the Whitechapel murders of ...

.'' (2001). Directed by the Hughes Brothers

In professional wrestling, TNT is a tag team consisting of twin brothers Terrell Hughes and Terrence Hughes (born February 25, 1995), the sons of TNA and WWE Hall of Famer Devon "D-Von Dudley" Hughes.

Early lives

Terrell and Terrence competed ...

, the film casts Katrin Cartlidge

Katrin Juliet Cartlidge (15 May 1961 – 7 September 2002) was an English actress. She first appeared on screen as Lucy Collins in the Channel 4 soap opera ''Brookside (TV series), Brookside'' (1982–1983), before going on to win the 1997 ...

as Annie Chapman.

Television

* ''Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer who was active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer was also ...

'' (1988). A Thames Television

Thames Television, commonly simplified to just Thames, was a franchise holder for a region of the British ITV television network serving London and surrounding areas from 30 July 1968 until the night of 31 December 1992.

Thames Television broa ...

film drama series starring Michael Caine

Sir Michael Caine (born Maurice Joseph Micklewhite, 14 March 1933) is a retired English actor. Known for his distinct Cockney accent, he has appeared in more than 160 films over Michael Caine filmography, a career that spanned eight decades an ...

. Annie Chapman is played by actress Deirdre Costello.

* ''The Real Jack the Ripper'' (2010). Directed by David Mortin, this series casts Sharon Buhagiar as Annie Chapman and was first broadcast on 31 August 2010.

* ''Jack the Ripper: The Definitive Story'' (2011). A two-hour documentary which references original police reports and eyewitness accounts pertaining to the Whitechapel Murderer. Chapman is portrayed by Dianne Learmouth.

Drama

* ''Jack, the Last Victim'' (2005). Thismusical

Musical is the adjective of music.

Musical may also refer to:

* Musical theatre, a performance art that combines songs, spoken dialogue, acting and dance

* Musical film

Musical film is a film genre in which songs by the Character (arts), charac ...

casts Michelle Jeffry as Annie Chapman.

See also

*Cold case

''Cold Case'' is an American police procedural crime drama television series. It ran on CBS from September 28, 2003, to May 2, 2010. The series revolved around a fictionalized Philadelphia Police Department division that specializes in invest ...

* List of serial killers before 1900

The following is a list of serial killers i.e. a person who murders more than one person, in two or more separate events over a period of time, for primarily psychological reasons''Macmillan Encyclopedia of Death and Dying'' entry o"Serial Killer ...

* Unsolved murders in the United Kingdom

This is an incomplete list of unsolved known and presumed murders in the United Kingdom. It does not include any of the 3,000 or so unsolved murders that took place in Northern Ireland because of the Troubles or any IRA attacks that took place ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* Begg, Paul (2003). ''Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History''. London: Pearson Education. * Begg, Paul (2004). ''Jack the Ripper: The Facts''. Barnes & Noble Books. * Bell, Neil R. A. (2016). ''Capturing Jack the Ripper: In the Boots of a Bobby in Victorian England''. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. * Cook, Andrew (2009). ''Jack the Ripper''. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. * Eddleston, John J. (2002). ''Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia''. London: Metro Books. * Evans, Stewart P.; Rumbelow, Donald (2006). ''Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates''. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. * Evans, Stewart P.; Skinner, Keith (2000). ''The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook: An Illustrated Encyclopedia''. London: Constable and Robinson. * Evans, Stewart P.; Skinner, Keith (2001). ''Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell''. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. * Fido, Martin (1987). ''The Crimes, Death and Detection of Jack the Ripper''. Vermont: Trafalgar Square. * Gordon, R. Michael (2000). ''Alias Jack the Ripper: Beyond the Usual Whitechapel Suspects''. North Carolina: McFarland Publishing. * Harris, Melvin (1994). ''The True Face of Jack the Ripper''. London: Michael O'Mara Books Ltd. * Holmes, Ronald M.; Holmes, Stephen T. (2002). ''Profiling Violent Crimes: An Investigative Tool''. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc. * Honeycombe, Gordon (1982). ''The Murders of the Black Museum: 1870–1970''. London: Bloomsbury Books. * Lynch, Terry; Davies, David (2008). ''Jack the Ripper: The Whitechapel Murderer''. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. * Marriott, Trevor (2005). ''Jack the Ripper: The 21st Century Investigation''. London: John Blake. * Rumbelow, Donald (2004). ''The Complete Jack the Ripper: Fully Revised and Updated''. Penguin Books. * Sugden, Philip (2002). ''The Complete History of Jack the Ripper''. Carroll & Graf Publishers. * Waddell, Bill (1993). ''The Black Museum: New Scotland Yard''. London: Little, Brown and Company. * Whittington-Egan, Richard; Whittington-Egan, Molly (1992). ''The Murder Almanac''. Glasgow: Neil Wilson Publishing. * Whittington-Egan, Richard (2013). ''Jack the Ripper: The Definitive Casebook''. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. * Wilson, Colin; Odell, Robin (1987) ''Jack the Ripper: Summing Up and Verdict''. Bantam Press.External links

''Contemporary news article''

pertaining to the murder of Annie Chapman *

BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broad ...

article pertaining to thmurders committed by Jack the Ripper

* The Whitechapel Murder Victims: Annie Chapman a

whitechapeljack.com

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chapman, Annie 1840 births 1888 deaths People murdered in 1888 19th-century English women English female prostitutes English murder victims Female murder victims Jack the Ripper victims People from Paddington Women of the Victorian era