Anna Van Schurman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anna Maria van Schurman (November 5, 1607 – May 4, 1678) was a

Van Schurman was born in

Van Schurman was born in

in the

In her 60s, Schurman emerged as one of the principal leaders of the

In her 60s, Schurman emerged as one of the principal leaders of the

Many of Schurman's writings were published during her lifetime in multiple editions, although some of her writings have been lost. Her most famous book was the ''Nobiliss. Virginis Annae Mariae a Schurman Opuscula Hebraea Graeca Latina et Gallica, Prosaica et Metrica'' (''Minor works in Hebrew, Greek, Latin and French in prose and poetry by the most noble Anne Maria van Schurman''). It was published 1648 by

Many of Schurman's writings were published during her lifetime in multiple editions, although some of her writings have been lost. Her most famous book was the ''Nobiliss. Virginis Annae Mariae a Schurman Opuscula Hebraea Graeca Latina et Gallica, Prosaica et Metrica'' (''Minor works in Hebrew, Greek, Latin and French in prose and poetry by the most noble Anne Maria van Schurman''). It was published 1648 by

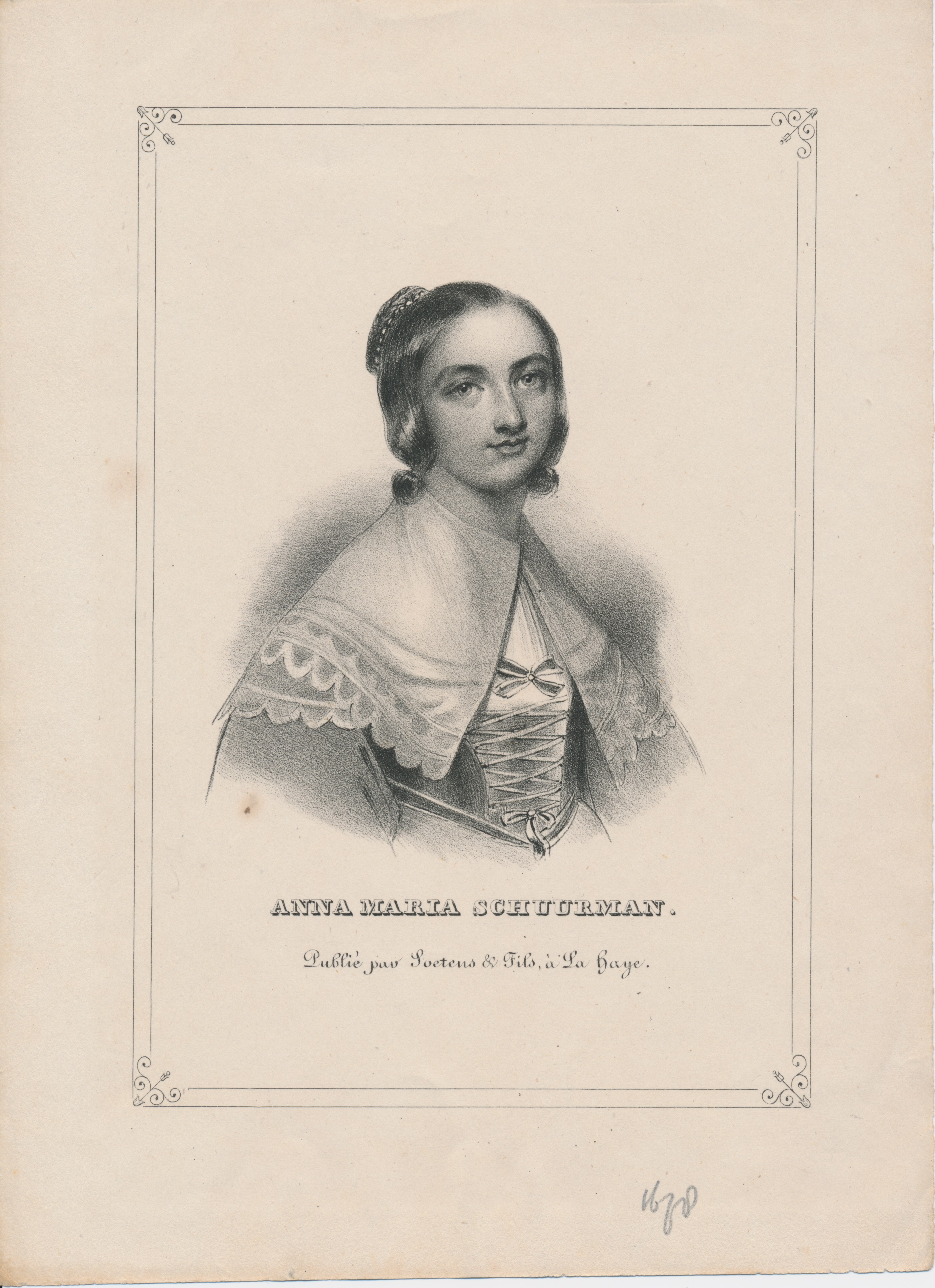

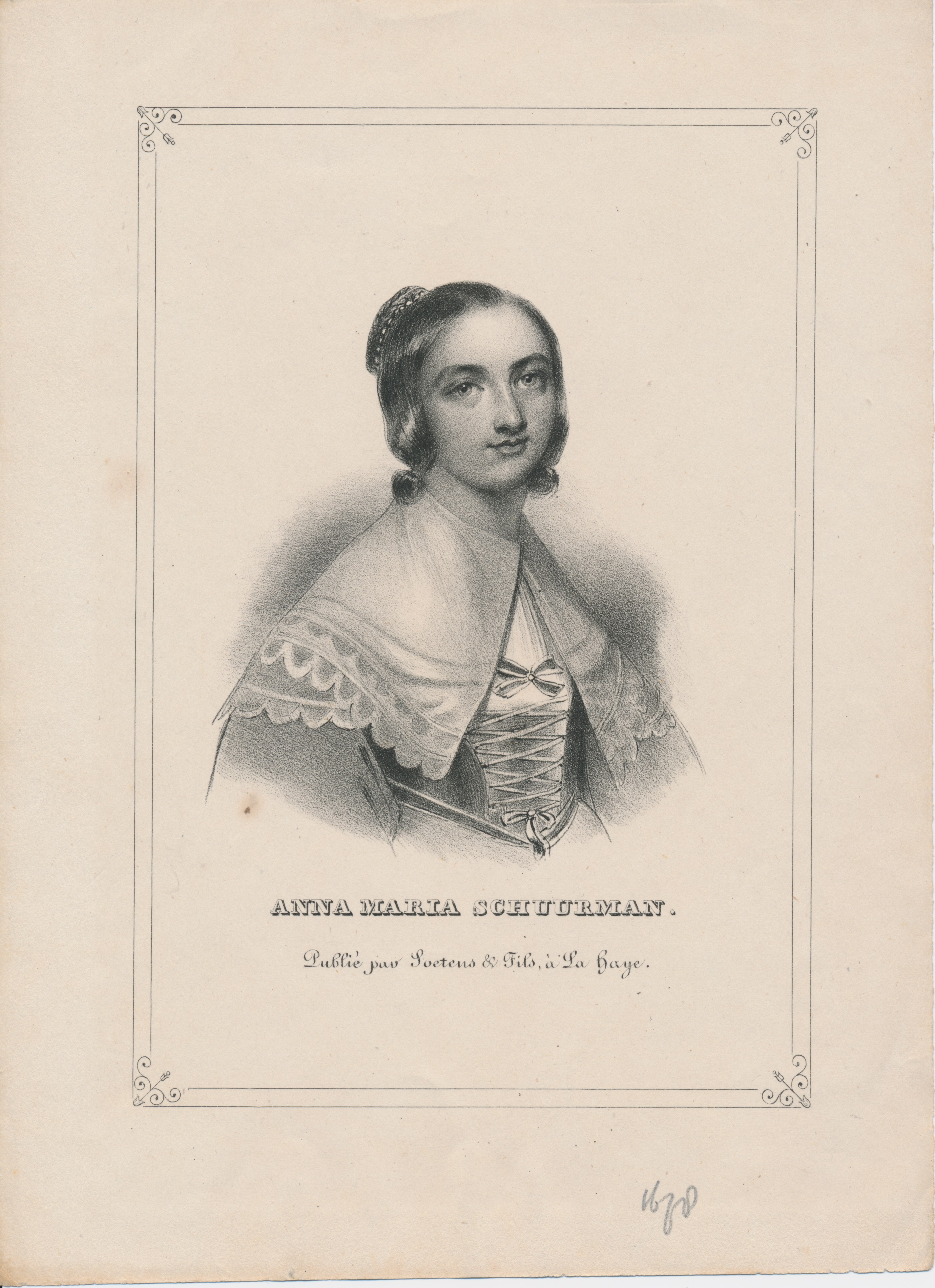

When Anna Maria van Schurman demonstrated her artistic talent early on, her father sent her to study with the famous engraver, Magdalena van de Passe, in the 1630s. Her first known engraving was a self-portrait, created in 1633. She found it difficult to depict hands and thus found ways to hide them in all of her self-portraits. In another self-portrait engraving she created in 1640, she included the Latin inscription "Cernitis hic picta nostros in imagine vultus: si negat ars formā gratia vestra dabit." This translates in English to "''See my likeness depicted in this portrait: May your favor perfect the work where art has failed."''

When Anna Maria van Schurman demonstrated her artistic talent early on, her father sent her to study with the famous engraver, Magdalena van de Passe, in the 1630s. Her first known engraving was a self-portrait, created in 1633. She found it difficult to depict hands and thus found ways to hide them in all of her self-portraits. In another self-portrait engraving she created in 1640, she included the Latin inscription "Cernitis hic picta nostros in imagine vultus: si negat ars formā gratia vestra dabit." This translates in English to "''See my likeness depicted in this portrait: May your favor perfect the work where art has failed."''

free PDF

*Bo Karen Lee: ''I wish to be nothing'': the role of self-denial in the mystical theology of A. M. van Schurman in: ''Women, Gender and Radical Religion in Early Modern Europe.'' Ed. Sylvia Brown. Leiden: 2008

27 S. online at google-books

*Katharina M. Wilson and Frank J. Warnke (eds.), ''Women Writers of the Seventeenth Century'', Athens: U. of Georgia Press, (1989) pp 164–185 *Mirjam de Baar et al. (eds.), ''Choosing the Better Part. Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678)'', Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, (1996). *Mirjam de Baar: ''Gender, genre and authority in seventeenth-century religious writing: Anna Maria van Schurman and

30p. free PDF

*Anne R. Larsen, "Anna Maria van Schurman, 'The Star of Utrecht': The Educational Vision and Reception of a Savante", omen and Gender in the Early Modern World Abingdon: Routledge, 2016. *Anna Maria van Schurman, ''Whether a Christian Woman Should Be Educated and Other Writing from Her Intellectual Circle'', ed and trans by Joyce Irwin, Chicago 1998

online at google-books

*Lennep, J, Herman F. C. Kate, and W P. Hoevenaar

Galerij Van Beroemde Nederlanders Uit Het Tijdvak Van Frederik Hendrik

Utrecht: L.E. Bosch en Zoon, 1868. *Martine van Elk, ''Early Modern Women's Writing: Domesticity, Privacy, and the Public Sphere in England and the Dutch Republic'', Cham: Palgrave/Springer, 2017 .

annamariavanschurman.org

(by Pieta van Beek)

National Gallery – Jan Lievens' portrait of Anna Maria van Schurman

Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

painter

Painting is a Visual arts, visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or "Support (art), support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with ...

, engraver, poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator (thought, thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral t ...

, classical scholar

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

, philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, and feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

writer who is best known for her exceptional learning and her defence of female education

Female education is a catch-all term for a complex set of issues and debates surrounding education (primary education, secondary education, tertiary education, and health education in particular) for girls and women. It is frequently called girls ...

. She was a highly educated woman, who excelled in art, music, and literature, and became a polyglot

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. When the languages are just two, it is usually called bilingualism. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolin ...

proficient in fourteen languages, including Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

, Biblical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew ( or ), also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite languages, Canaanitic branch of the Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Isra ...

, Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

, Syriac, Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

, and Ethiopic, as well as various contemporary European languages

There are over 250 languages indigenous to Europe, and most belong to the Indo-European language family. Out of a total European population of 744 million as of 2018, some 94% are native speakers of an Indo-European language. The three larges ...

. She was the first woman to study, unofficially, at a Dutch university.

Life

Van Schurman was born in

Van Schurman was born in Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

, at the time part of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, a daughter of wealthy parents, Frederik van Schurman, from Antwerp (d. 1623) and Eva von Harff de Dreiborn. At four years old she could read

Read or READ may refer to:

Computing

* Read (computer), to retrieve data from a storage device

* Read (system call), a low-level IO function on a file descriptor in a computer

* Read (Unix), a command in Unix operating systems

Places

* Read, L ...

. When she was six, she had mastered creating highly intricate paper cut-outs that surpassed every other child's her age. At the age of ten, she learned embroidery in three hours. In some of her writings, she talks about how she invented the technique of sculpting in wax, saying, "I had to discover many things which nobody was able to teach me." Her self-portrait wax sculpture was so lifelike, especially the necklace, that her friend, the Princess of Nassau, had to prick one with a pin just to be sure it was not real.Honig, Elizabeth Alice. "The Art of Being "Artistic": Dutch Women's Creative Practices in the 17th Century." Woman's Art Journal 22, no. 2 (2001): 31-39. doi:10.2307/1358900. Between 1613 and 1615, her family moved to Utrecht

Utrecht ( ; ; ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city of the Netherlands, as well as the capital and the most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of Utrecht (province), Utrecht. The ...

, and about ten years later they moved again, this time to Franeker

Franeker (; ) is one of the eleven historical City rights in the Low Countries, cities of Friesland and capital of the municipality of Waadhoeke. It is located north of the Van Harinxmakanaal and about west of Leeuwarden. As of 2023, it had 13,0 ...

in Friesland, where she lived in the Martenahuis

The Martenahuis or Martenastins () is a stins (estate) in the centre of the Netherlands, Dutch city of Franeker, Friesland. The building is located on the Voorstraat. The Martenahuis dates from 1502 when it was built by order of the chieftain Hes ...

. From about 11 years old, Schurman was taught Latin and other subjects by her father along with his sons, an unusual decision at a time when girls in noble families were not generally tutored in the classics.Anna Maria van Schurmanin the

RKD

The Netherlands Institute for Art History or RKD (Dutch: ), previously Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie (RKD), is located in The Hague and is home to the largest art history center in the world. The center specializes in document ...

To learn Latin she was given Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People, fictional characters and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

:

:* Seneca the Elder (c. 54 BC – c. AD 39), a Roman rhetorician, writer and father ...

to read by her father. The private education and self-study were complemented through correspondence and discussions with notables such as André Rivet

André Rivet (Andreas Rivetus) (August 1572 – 7 January 1651) was a French Huguenot theologian.

Life

Rivet was born at Saint-Maixent, 43 km (27 mi) southwest of Poitiers, France. After completing his education at Bern, he studied the ...

and Friedrich Spanheim

Friedrich Spanheim the Elder (January 1, 1600, Amberg – May 14, 1649, Leiden) was a Calvinistic theology professor at the University of Leiden.

Life

He entered in 1614 the University of Heidelberg where he studied philology and philosop ...

, both professors of Leiden University

Leiden University (abbreviated as ''LEI''; ) is a Public university, public research university in Leiden, Netherlands. Established in 1575 by William the Silent, William, Prince of Orange as a Protestantism, Protestant institution, it holds the d ...

, and the family's neighbour Gisbertus Voetius

Gisbertus Voetius ( Latinized version of the Dutch name Gijsbert Voet ; 3 March 1589 – 1 November 1676) was a Dutch Calvinist theologian, pastor, and professor.

Life

He was born at Heusden, in the Dutch Republic, studied at Leiden, and in 16 ...

, a professor at the University of Utrecht

Utrecht University (UU; , formerly ''Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht'') is a public research university in Utrecht, Netherlands. Established , it is one of the oldest universities in the Netherlands. In 2023, it had an enrollment of 39,769 students, a ...

. She excelled at painting

Painting is a Visual arts, visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or "Support (art), support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with ...

, paper-cutting

Papercutting or paper cutting is the art of paper designs that has evolved all over the world to adapt to different cultural styles. One traditional distinction most styles share is that the designs are cut from a single sheet of paper as oppo ...

, embroidery

Embroidery is the art of decorating Textile, fabric or other materials using a Sewing needle, needle to stitch Yarn, thread or yarn. It is one of the oldest forms of Textile arts, textile art, with origins dating back thousands of years across ...

, and wood carving

Wood carving (or woodcarving) is a form of woodworking by means of a cutting tool (knife) in one hand or a chisel by two hands or with one hand on a chisel and one hand on a mallet, resulting in a wooden figure or figurine, or in the sculpture, ...

. Another art form that she experimented with was calligraphy

Calligraphy () is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instruments. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined as "the art of giving form to signs in an e ...

, which she learned just from looking at a model-book. Once she mastered that, she invented styles that allowed her to write in many of the languages she knew. After her father's death, the family moved back to Utrecht in 1626. In her 20s, Schurman's home became a meeting point for intellectuals. Among her friends were Constantijn Huygens

Sir Constantijn Huygens, Lord of Zuilichem ( , , ; 4 September 159628 March 1687), was a Dutch Golden Age poet and composer. He was also secretary to two Princes of Orange: Frederick Henry and William II, and the father of the scientist C ...

, Johan van Beverwijck

Johan van Beverwijck or Johannes Beverovicius (Dordrecht, 17 November 1594 - 19 January 1647) was a Dutch doctor and writer. Van Beverwijck was interested in new developments and contributed to medical science with his own experiments.

Biography ...

, Jacob de Witt

Jacob de Witt, '' heer van Manezee, Melissant and Comstryen'' (7 February 1589 – 10 January 1674) was a burgomaster of Dordrecht and the son of a timber merchant. De Witt was an influential member of the Dutch States Party, and was in opposit ...

, Cornelius Boy, Margaretha van Godewijk

Margaretha van Godewijk (30 August 1627, Dordrecht – 2 November 1677, Dordrecht), was a Dutch Golden Age poet and painter.

Biography

According to Houbraken her father was a teacher at the Latin school in Dordrecht who taught her Greek, Latin, I ...

and Utricia Ogle. In the 1630s she studied engraving with Magdalena van de Passe. Combining the techniques of engraving with her skills in calligraphy, her renowned engraved calligraphy pieces gained the attention of all who saw them, including her contemporaries. Despite her playfulness and experimentation, Anna Maria was very serious about her art, and her contemporaries knew it. She herself said that she was "immensely gifted by God in the arts."

In 1634, due to her distinction in Latin, she was invited to write a poem for the opening of the University of Utrecht

Utrecht University (UU; , formerly ''Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht'') is a public research university in Utrecht, Netherlands. Established , it is one of the oldest universities in the Netherlands. In 2023, it had an enrollment of 39,769 students, a ...

. In the poem she celebrated the city of Utrecht and the new university. She noted the potential for the university to help the city cope with the economic impacts of the floods and the shifting course of the river Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

. She also challenged the exclusion of women from the university. In response to her complaint, the university authorities allowed her to attend professor Voetius' lectures. In 1636 she became the first female student at the university, or at any Dutch university. Women at that time were not permitted to study at a university in Protestant Netherlands, and when she attended lectures she sat behind a screen or in a curtained booth so that the male students could not see her.Van Beek 2010: 60 and n. 97, who points out that we know this from reports by Van Schurman's fellow students Descartes and Hoornbeeck. At the university she studied Hebrew, Arabic, Chaldee, Syriac and Ethiopian. Her interest in philosophy and theology and her artistic talent contributed to her fame and reputation as the "Star of Utrecht". By the 1640s she was fluent in 14 languages and wrote in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, French, Arabic, Persian, Ethiopian, German and Dutch.

According to her contemporary Pierre Yvon, Schurman had an excellent command of mathematics, geography and astronomy. The pious young scholar appears to have had a number of suitors. After his wife died in 1631, Constantijn Huygens

Sir Constantijn Huygens, Lord of Zuilichem ( , , ; 4 September 159628 March 1687), was a Dutch Golden Age poet and composer. He was also secretary to two Princes of Orange: Frederick Henry and William II, and the father of the scientist C ...

asked for Schurman's hand in marriage and wrote 10 poems in three languages to her in 1634. Huygens was teased by other Dutch intellectuals. Schurman's commitment to celibacy and her studies seemed to be unwavering. When she chose the phrase ''Amor Meus Crucifixus Est'' (''My Love Has Been Crucified'') as her motto, her intellectual friends were convinced that her choice not to marry was rooted in her piety, rather than her scholarship.

Schurman produced delicate engravings by using a diamond on glass, sculpture, wax modelling, and the carving of ivory and wood. She painted, especially portraits, becoming the first known Dutch painter to use pastel

A pastel () is an art medium that consists of powdered pigment and a binder (material), binder. It can exist in a variety of forms, including a stick, a square, a pebble, and a pan of color, among other forms. The pigments used in pastels are ...

in a portrait. She gained honorary admission to the St. Luke Guild of painters in 1643, signalling public recognition of her art.

Schurman corresponded with the Danish noblewoman Birgitte Thott

Birgitte (Bridget) Thott (17 June 1610 – 8 April 1662) was a Danish writer, scholar and feminist, known for her learning. She was fluent and literate in Latin (her main area of study) along with many other languages. She translated many publish ...

, who translated classical authors and religious writings. Thott's translation of Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People, fictional characters and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

:

:* Seneca the Elder (c. 54 BC – c. AD 39), a Roman rhetorician, writer and father ...

's philosophical works included a preface in which she argued for women's right to study. Thott stated that she translated classical works because few women were able to read Latin. Schurman publicly praised Thott and called her the "tenth Muse of the North". Schurman through correspondence established a network of learned women across Europe. She corresponded in Latin and Hebrew with Dorothea Moore, in Greek with Bathsua Makin

Bathsua Reginald Makin (; 1600 – c. 1675) was a teacher who contributed to the emerging criticism of woman's position in the domestic and public spheres in 17th-century England. Herself a highly educated woman, Makin was referred to as Englan ...

, in French, Latin and Hebrew with Marie de Gournay

Marie de Gournay (; 6 October 1565, Paris – 13 July 1645) was a French writer, who wrote a novel and a number of other literary compositions, including ''The Equality of Men and Women'' (''Égalité des hommes et des femmes'', 1622) and ' ...

and , in Latin and French with Elizabeth of Bohemia

Elizabeth Stuart (19 August 1596 – 13 February 1662) was Electress of the Palatinate and briefly Queen of Bohemia as the wife of Frederick V of the Palatinate. The couple's selection for the crown by the nobles of Bohemia was part of the po ...

, and in Latin with Queen Christina of Sweden

Christina (; 18 December O.S. 8 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 8 December1626 – 19 April 1689), a member of the House of Vasa, was Monarchy of Sweden, Queen of Sweden from ...

. A frequent topic in this correspondence was the education of women. Schurman in the correspondence expressed her admiration for educated women like Lady Jane Gray and Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

.

An unauthorised version of Schurman's writings on women's education was published in 1638 in Paris under the title ''Dissertatio De Ingenii Muliebris ad Doctrinam, & meliores Litteras aptitudine''. As the unauthorised collection of her writings circulated, Schurman decided to publish an authoritative Latin treatise in 1641. In 1657 the treatise was published in English under the title ''The Learned Maid or, Whether a Maid may be a Scholar''.

The Labadists

In her 60s, Schurman emerged as one of the principal leaders of the

In her 60s, Schurman emerged as one of the principal leaders of the Labadists

The Labadists were a 17th-century Protestant religious community movement founded by Jean de Labadie (1610–1674), a French pietist. The movement derived its name from that of its founder.

Jean de Labadie's life

Jean de Labadie (1610–1674 ...

. In the 1660s Schurman had become increasingly disillusioned with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands

The Reformed Churches in the Netherlands (, abbreviated ''Gereformeerde kerk'') was the second largest Protestant church in the Netherlands and one of the two major Calvinist denominations along with the Dutch Reformed Church since 1892 unti ...

. She made the reformation of the church her goal. Along with corresponding with ministers, she travelled throughout the country and organised meetings with them. She lamented the lack of spiritual devotion and the "exhibits of the ecclesiastics" that occupied the church's pulpits.

In 1661 Schurman's brother studied theology with the Hebrew scholar Johannes Buxtorf

Johannes Buxtorf () (December 25, 1564September 13, 1629) was a celebrated Hebraist, member of a family of Orientalists; professor of Hebrew for thirty-nine years at Basel and was known by the title, "Master of the Rabbis". His massive tome, '' ...

in Basel and learned about the defrocked French priest Jean de Labadie. He travelled to Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

to meet him. In 1662 he corresponded with Schurman at length about Labadie's teachings. When Labadie and a small number of followers stopped over in Utrecht on the way to Middelburg Middelburg may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Europe

* Middelburg, Zeeland, the capital city of the province of Zeeland, southwestern Netherlands

** Roman Catholic Diocese of Middelburg, a former Catholic diocese with its see in the Zeeland ...

, they lodged in Schurman's house. Labadie became the pastor of Middelburg, preaching millenarianism

Millenarianism or millenarism () is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming fundamental transformation of society, after which "all things will be changed". Millenarianism exists in various cultures and re ...

, arguing for moral regeneration and that believers should live apart from unbelievers. Schurman supported him even when he was removed as a pastor. When in late 1669 Labadie settled in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

to establish a separatist church, Schurman sold her house and part of her library. She joined Labadie's sectarian community. In March 1669 she broke with the Reformed Church when she published a 10-page pamphlet ''On the Reformation necessary at present in the Church of Christ''. She denounced the church men for trampling on "celestial wisdom", arguing that the people of God should be separated from the "mondains" through "hatred of the world" and "divine love".

A public smear campaign followed. Schurman was attacked by her intellectual friends, including Huygens and Voetius. Her writing style became forthright and confident. When the Labadists had to leave Amsterdam, Schurman secured an invitation from her friend Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, who in 1667 had become abbess at the Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

''Damenstift'' of Herford Abbey

Herford Abbey () was the oldest women's religious house in the Duchy of Saxony. It was founded as a house of secular canonesses in 789, initially in Müdehorst (near the modern Bielefeld) by a nobleman called Waltger, who moved it in about 800 ont ...

. The 50 Labadists lived there between 1670 and 1672. At Herdford Schurman continued her art work and the Labadists maintained a printing press. Schurman was referred to by the Labadists as ''Mama'', Labadie as ''Papa''. Rumours had it that Labadie and Schurman had married; however, he married Lucia van Sommelsdijck. In 1672 the Labadists moved to Altona in Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

, as Elisabeth of Bohemia had advocated on their behalf in correspondence with the King of Denmark. In 1673 Schurman published ''Eukleria, or Choosing the Better Part'', a reference to Luke 10:42 when Mary chooses the better part by sitting at the feet of Christ. In it she derided Gisbertus Voetius

Gisbertus Voetius ( Latinized version of the Dutch name Gijsbert Voet ; 3 March 1589 – 1 November 1676) was a Dutch Calvinist theologian, pastor, and professor.

Life

He was born at Heusden, in the Dutch Republic, studied at Leiden, and in 16 ...

's opposition to her admiration for Saint Paula

Paula of Rome (AD 347–404) was an ancient Roman Christian saint and early Desert Mother. A member of one of the richest senatorial families which claimed descent from Agamemnon, Paula was the daughter of Blesilla and Rogatus, from the great ...

, a disciple of St Jerome

Jerome (; ; ; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian priest, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known for his translation of the Bible i ...

, who had helped to translate the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

into Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

. Voetius argued that women should have a limited public role and that anything else was feminine impropriety. ''Eukleria'' was well received by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to ...

and prominent pietists, including Johann Jacob Schütz

Johann Jakob Schütz (7 September 1640, Frankfurt – 22 May 1690, Frankfurt) was a German lawyer and hymnwriter. One of his hymns was reworked by Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (German: Help:IPA/Standard German, �joːha ...

, Philipp Jakob Spener

Philipp Jakob Spener (23 January 1635 – 5 February 1705) was a German Lutheran theologian who essentially founded what became known as Pietism. He was later dubbed the "Father of Pietism". A prolific writer, his two main works, ''Pia desider ...

and .

When Labadie died in 1674, Schurman investigated the possibility of moving to England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, corresponding with the Latin scholar Lucy Hutchinson

Lucy Hutchinson (; 29 January 1620 – October 1681) was an English translator, poet, and biographer, and the first person to translate the complete text of Lucretius's ''De rerum natura'' (''On the Nature of Things'') into English verse, ...

and the theologian John Owen on the matter. But the Labadists moved to the village Wieuwerd in Friesland

Friesland ( ; ; official ), historically and traditionally known as Frisia (), named after the Frisians, is a Provinces of the Netherlands, province of the Netherlands located in the country's northern part. It is situated west of Groningen (p ...

and attracted numerous new members, including Maria Sibylla Merian

Maria Sibylla Merian (2 April 164713 January 1717) was a German Entomology, entomologist, naturalist and scientific illustrator. She was one of the earliest European naturalists to document observations about insects directly. Merian was a desce ...

. About 400 Labadists practiced absolute detachment from worldly values. They attempted to return to early church practices, sharing all property. In the final years of her life Schurman was housebound due to severe rheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorders are conditions causing chronic, often intermittent pain affecting the joints or connective tissue. Rheumatism does not designate any specific disorder, but covers at least 200 different conditions, including a ...

. She continued to write, keeping up correspondence and working on the second part of ''Eukleria''. She died aged 70 in 1678.

Published writings

Many of Schurman's writings were published during her lifetime in multiple editions, although some of her writings have been lost. Her most famous book was the ''Nobiliss. Virginis Annae Mariae a Schurman Opuscula Hebraea Graeca Latina et Gallica, Prosaica et Metrica'' (''Minor works in Hebrew, Greek, Latin and French in prose and poetry by the most noble Anne Maria van Schurman''). It was published 1648 by

Many of Schurman's writings were published during her lifetime in multiple editions, although some of her writings have been lost. Her most famous book was the ''Nobiliss. Virginis Annae Mariae a Schurman Opuscula Hebraea Graeca Latina et Gallica, Prosaica et Metrica'' (''Minor works in Hebrew, Greek, Latin and French in prose and poetry by the most noble Anne Maria van Schurman''). It was published 1648 by Friedrich Spanheim

Friedrich Spanheim the Elder (January 1, 1600, Amberg – May 14, 1649, Leiden) was a Calvinistic theology professor at the University of Leiden.

Life

He entered in 1614 the University of Heidelberg where he studied philology and philosop ...

, professor of theology at Leiden University

Leiden University (abbreviated as ''LEI''; ) is a Public university, public research university in Leiden, Netherlands. Established in 1575 by William the Silent, William, Prince of Orange as a Protestantism, Protestant institution, it holds the d ...

through the Leiden-based publisher Elzeviers.

Schurman's ''The Learned Maid or, Whether a Maid may be a Scholar'' grew out of her correspondence on women's education with theologians and scholars across Europe. In it she advances Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey (1536/1537 – 12 February 1554), also known as Lady Jane Dudley after her marriage, and nicknamed as the "Nine Days Queen", was an English noblewoman who was proclaimed Queen of England and Ireland on 10 July 1553 and reigned ...

as an example of the value of female education. Schurman argued that educating women in languages and the Bible would increase their love of God. While an increasing number of royal and wealthy families chose to educate their daughters, girls and women did not have formal access to education. Schurman argued that "A Maid may be a Scholar... The assertion may be proved both from the property of the form of this subject; or the rational soul: and from the very acts and effects themselves. For it is manifest that Maids do actually learn any arts and science." In arguing that women had rational souls she foreshadowed the Cartesian argument for human reason, underpinning her assertion that women had a right to be educated. Schurman and René Descartes

René Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramou ...

corresponded, and while they disagreed on the interpretation of the Bible they both thought that reason was central in the human identity.

''The Learned Maid'' included correspondence with the theologian André Rivet

André Rivet (Andreas Rivetus) (August 1572 – 7 January 1651) was a French Huguenot theologian.

Life

Rivet was born at Saint-Maixent, 43 km (27 mi) southwest of Poitiers, France. After completing his education at Bern, he studied the ...

. In her correspondence with Rivet, Schurman explained that women such as Marie de Gournay

Marie de Gournay (; 6 October 1565, Paris – 13 July 1645) was a French writer, who wrote a novel and a number of other literary compositions, including ''The Equality of Men and Women'' (''Égalité des hommes et des femmes'', 1622) and ' ...

had already proven that man and woman are equal, so she would not "bore her readers with repetition". Like Rivet, Schurman argued in ''The Learned Maid'' for education on the basis of moral grounds, because "ignorance and idleness cause vice". But Schurman also took the position that "whoever by nature has a desire for arts and science is suited to arts and science: women have this desire, therefore women are suited to arts and science". However, Schurman did not advocate for universal education

Universal access to education is the ability of all people to have equal opportunity in education, regardless of their social class, race, gender, sexuality, ethnic background or physical and mental disabilities. The term is used both in colle ...

, or the education for women of the lower classes. She took the view that ladies of upper classes should have access to higher education. Schurman made the point that women could make a valuable contribution to society, and argued that it was also necessary for their happiness to study theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

, philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and the sciences

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

. In reference to ''The Learned Maid'', Rivet cautioned her in a letter that "although you have shown us this with grace, your persuasions are futile... You may have many admirers, but none of them agree with you."

Engravings

When Anna Maria van Schurman demonstrated her artistic talent early on, her father sent her to study with the famous engraver, Magdalena van de Passe, in the 1630s. Her first known engraving was a self-portrait, created in 1633. She found it difficult to depict hands and thus found ways to hide them in all of her self-portraits. In another self-portrait engraving she created in 1640, she included the Latin inscription "Cernitis hic picta nostros in imagine vultus: si negat ars formā gratia vestra dabit." This translates in English to "''See my likeness depicted in this portrait: May your favor perfect the work where art has failed."''

When Anna Maria van Schurman demonstrated her artistic talent early on, her father sent her to study with the famous engraver, Magdalena van de Passe, in the 1630s. Her first known engraving was a self-portrait, created in 1633. She found it difficult to depict hands and thus found ways to hide them in all of her self-portraits. In another self-portrait engraving she created in 1640, she included the Latin inscription "Cernitis hic picta nostros in imagine vultus: si negat ars formā gratia vestra dabit." This translates in English to "''See my likeness depicted in this portrait: May your favor perfect the work where art has failed."''

Published works

''Incomplete list'' *"De Vitæ Termino" (On the End of Life). Published in Leiden, 1639. Translated into Dutch as "Pael-steen van den tijt onses levens," published in Dordrecht, 1639. * Paris, 1638, and Leiden, 1641. Translated into many languages, including Dutch, French (1646), and English entitled :This work argued, using the medieval technique ofsyllogism

A syllogism (, ''syllogismos'', 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

In its earliest form (defin ...

, that women should be educated in all matters but should not use their education in professional activity or employment and it should not be allowed to interfere in their domestic duties. For its time this was a radical position.

*

:This is an edition of her collected works, including correspondence in French, Latin, Greek and Hebrew, were published by the house of Elsevier

Elsevier ( ) is a Dutch academic publishing company specializing in scientific, technical, and medical content. Its products include journals such as ''The Lancet'', ''Cell (journal), Cell'', the ScienceDirect collection of electronic journals, ...

, edited by Friedrich Spanheim

Friedrich Spanheim the Elder (January 1, 1600, Amberg – May 14, 1649, Leiden) was a Calvinistic theology professor at the University of Leiden.

Life

He entered in 1614 the University of Heidelberg where he studied philology and philosop ...

, another disciple of Labadie. Volume was reprinted in 1650, 1652, 1723 and 1749.

* (Euklēría, or Choosing the Better Part). Translated into Dutch and German.

:This is a defense of her choice to follow Labadie and a theological tract.

Tributes

*Judy Chicago

Judy Chicago (born Judith Sylvia Cohen; July 20, 1939) is an American feminist artist, art educator, and writer known for her large collaborative art installation pieces about birth and creation images, which examine the role of women in history ...

's feminist artwork ''The Dinner Party

''The Dinner Party'' is an installation artwork by American feminist artist Judy Chicago. There are 39 elaborate place settings on a triangular table for 39 mythical and historical famous women. Sacajawea, Sojourner Truth, Eleanor of Aquitaine, ...

'' (1979) features a place setting for van Schurman.

*Between 2000 and 2018, a marble bust of van Schurman was situated in the atrium of the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

of the Dutch Parliament in The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

.

*Van Schurman's name is shown on a blackboard showing a list of the most worthy people for a new version of ''The Good Place

''The Good Place'' is an American fantasy-comedy television series created by Michael Schur for NBC. The series premiered on September 19, 2016, and concluded on January 30, 2020, after four seasons consisting of 53 episodes.

Although the pl ...

'' in episode 11 of the fourth season.

Further reading

*Pieta van Beek: ''The first female university student: A.M.van Schurman'', Utrecht 2010, 280pfree PDF

*Bo Karen Lee: ''I wish to be nothing'': the role of self-denial in the mystical theology of A. M. van Schurman in: ''Women, Gender and Radical Religion in Early Modern Europe.'' Ed. Sylvia Brown. Leiden: 2008

27 S. online at google-books

*Katharina M. Wilson and Frank J. Warnke (eds.), ''Women Writers of the Seventeenth Century'', Athens: U. of Georgia Press, (1989) pp 164–185 *Mirjam de Baar et al. (eds.), ''Choosing the Better Part. Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678)'', Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, (1996). *Mirjam de Baar: ''Gender, genre and authority in seventeenth-century religious writing: Anna Maria van Schurman and

Antoinette Bourignon

Antoinette Bourignon de la Porte (13 January 161630 October 1680) was a French- Flemish mystic and adventurer. She taught that the end times would come soon and that the Last Judgment would then fall. Her belief was that she was chosen by God t ...

as contrasting examples''30p. free PDF

*Anne R. Larsen, "Anna Maria van Schurman, 'The Star of Utrecht': The Educational Vision and Reception of a Savante", omen and Gender in the Early Modern World Abingdon: Routledge, 2016. *Anna Maria van Schurman, ''Whether a Christian Woman Should Be Educated and Other Writing from Her Intellectual Circle'', ed and trans by Joyce Irwin, Chicago 1998

online at google-books

*Lennep, J, Herman F. C. Kate, and W P. Hoevenaar

Galerij Van Beroemde Nederlanders Uit Het Tijdvak Van Frederik Hendrik

Utrecht: L.E. Bosch en Zoon, 1868. *Martine van Elk, ''Early Modern Women's Writing: Domesticity, Privacy, and the Public Sphere in England and the Dutch Republic'', Cham: Palgrave/Springer, 2017 .

See also

*History of feminism

The history of feminism comprises the narratives (chronological or thematic) of the movements and ideologies which have aimed at equal rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending ...

*List of Orientalist artists

This is an incomplete list of artists who have produced works on Orientalism#Orientalist art, Orientalist subjects, drawn from the Islamic world or other parts of Asia. Many artists listed on this page worked in many genres, and Orientalist subj ...

*Orientalism

In art history, literature, and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world (or "Orient") by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. Orientalist painting, particularly of the Middle ...

References

Sources

annamariavanschurman.org

(by Pieta van Beek)

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Schurman, Anna Maria 1607 births 1678 deaths 17th-century Dutch philosophers 17th-century Dutch poets 17th-century Dutch women artists 17th-century Dutch women writers 17th-century Dutch engravers 17th-century German engravers 17th-century German philosophers 17th-century German poets 17th-century German women artists 17th-century German women writers 17th-century writers in Latin Artists from Cologne Artists from Utrecht (city) Dutch classical scholars Dutch glass artists Dutch Golden Age painters Dutch women painters Dutch women philosophers Dutch women poets Dutch wood engravers Proto-feminists Feminist writers German women philosophers German women poets Glass engravers Multilingual poets Multilingual writers Neo-Latin poets Orientalist painters Pietists Protestant philosophers Women classical scholars Dutch women engravers