Andrey Vyshinsky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

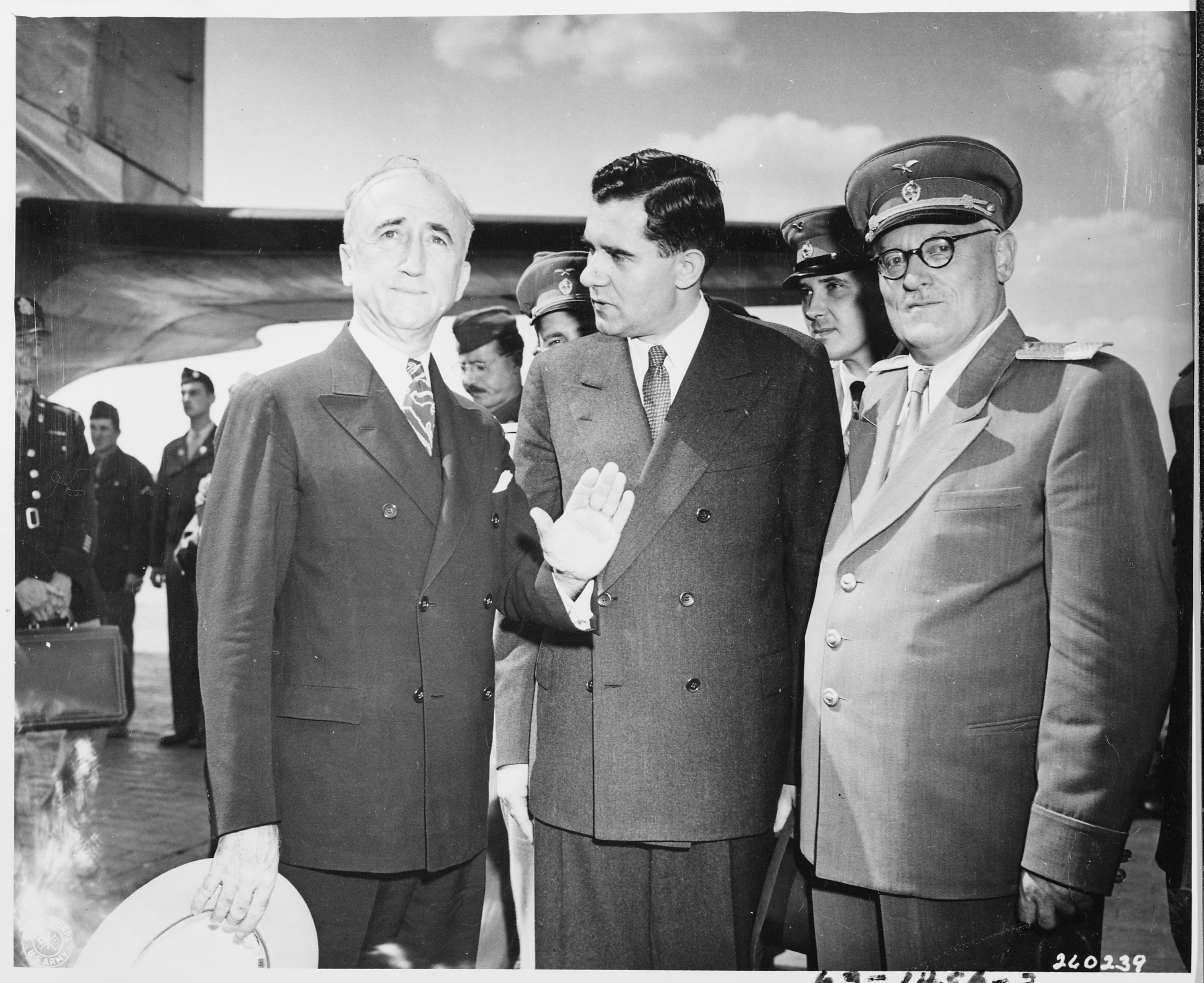

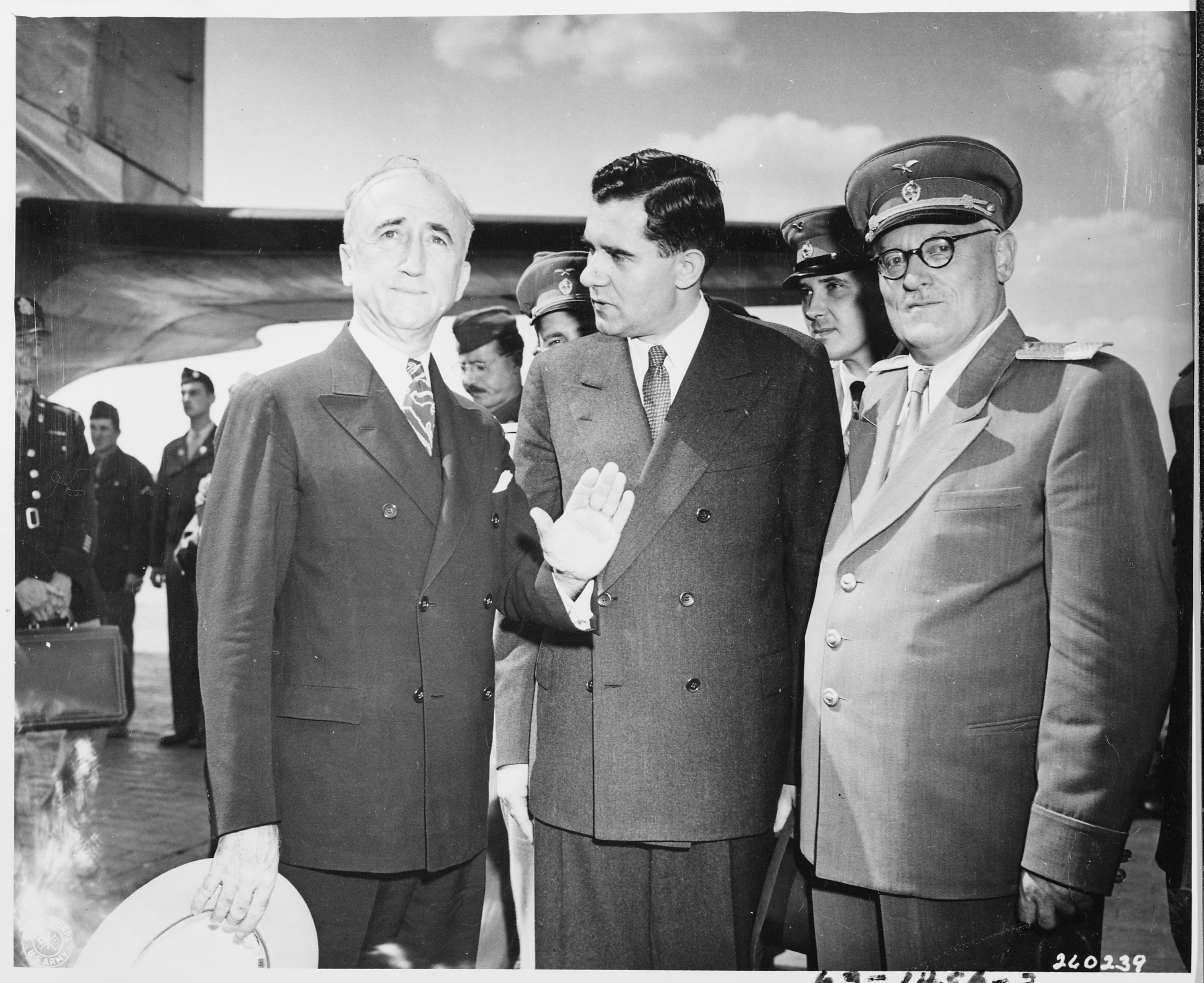

Andrey Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (; ) ( – 22 November 1954) was a Soviet politician,

He was responsible for the Soviet preparations for the trial of the major German war criminals by the International Military Tribunal.

In 1953, he was among the chief figures accused by the U.S. Congress Kersten Committee during its investigation of the Soviet

He was responsible for the Soviet preparations for the trial of the major German war criminals by the International Military Tribunal.

In 1953, he was among the chief figures accused by the U.S. Congress Kersten Committee during its investigation of the Soviet

"The Soviet Legal Narrative" - An essay by Anna Lukina about Vyshinsky as a theorist and his influence on the Nuremberg Trials and international law

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20060619201454/http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hiss/hissvenona.html Venona transcript #1822* {{DEFAULTSORT:Vyshinsky, Andrey 1883 births 1954 deaths 20th-century jurists 20th-century Russian politicians Politicians from Odesa People from Kherson Governorate Deputy heads of government of the Soviet Union Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union members Permanent representatives of the Soviet Union to the United Nations Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary (Soviet Union) Candidates of the Presidium of the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Members of the Central Committee of the 18th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Full Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Academic staff of Moscow State University Academic staff of the Plekhanov Russian University of Economics Rectors of Moscow State University Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Bolsheviks Mensheviks Ministers of foreign affairs of the Soviet Union First convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Second convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Fourth convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Recipients of the Stalin Prize Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour Great Purge perpetrators Trial of the Sixteen (Great Purge) Lawyers from the Russian Empire People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent Soviet people of Polish descent Ukrainian people of Polish descent Russian prosecutors Russian revolutionaries Soviet lawyers Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis Jurisprudence academics

jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyzes and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal education in law (a law degree) and often a Lawyer, legal prac ...

and diplomat

A diplomat (from ; romanization, romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state (polity), state, International organization, intergovernmental, or Non-governmental organization, nongovernmental institution to conduct diplomacy with one ...

.

He is best known as a state prosecutor of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

's Moscow Trials and in the Nuremberg trials. He was the Soviet Foreign Minister from 1949 to 1953, after having served as Deputy Foreign Minister under Vyacheslav Molotov since 1940. He also headed the Institute of State and Law in the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union.

Biography

Early life

Vyshinsky was born inOdessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

into a Polish Catholic family, which later moved to Baku

Baku (, ; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Azerbaijan, largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and in the Caucasus region. Baku is below sea level, which makes it the List of capital ci ...

. Early biographies portray his father, Yanuary Vyshinsky (Januarius Wyszyński), as a "well-prospering" "experienced inspector" (Russian: Ревизор); while later, undocumented, Stalin-era biographies such as that in the ''Great Soviet Encyclopedia

The ''Great Soviet Encyclopedia'' (GSE; , ''BSE'') is one of the largest Russian-language encyclopedias, published in the Soviet Union from 1926 to 1990. After 2002, the encyclopedia's data was partially included into the later ''Great Russian Enc ...

'' make him a pharmaceutical chemist. A talented student, Andrei Vyshinsky married Kara Mikhailova and became interested in revolutionary ideas. He began attending the Kiev University in 1901, but was expelled in 1902 for participating in revolutionary activities.

Vyshinsky returned to Baku, became a member of the Menshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

in 1903 and took an active part in the 1905 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, th ...

. As a result, in 1908 he was sentenced to prison and a few days later was sent to in Baku to serve his sentence. Here he first met Stalin: a fellow-inmate with whom he engaged in ideological disputes. After his release, he returned home to Baku for the birth of his daughter Zinaida in 1909. Soon thereafter, he returned to Kiev University and did quite well, graduating in 1913. He was even considered for a professorship, but his political past caught up with him, and he was forced to return to Baku.

Determined to practise law, he tried Moscow, where he became a successful lawyer, remained an active Menshevik, gave many passionate and incendiary speeches, and became involved in city government.

Russian Revolution and Civil War

After the February Revolution in 1917, he was appointed police commissioner of the Yakimanka District. As a minor official, he undersigned an order to arrestVladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

on charges of being a "German spy", according to the decision of the Minister of Justice of the Russian Provisional Government, but the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

quickly intervened, and the offices which had ordered the arrest were dissolved. In 1917, he became reacquainted with Stalin, who had become an important Bolshevik leader. Consequently, he joined the staff of the People's Commissariat of Food, which was responsible for Moscow's food supplies, and with the help of Stalin, Alexei Rykov

Alexei Ivanovich Rykov (25 February 188115 March 1938) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet politician and statesman, most prominent as premier of Russia and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Soviet Union from 1924 to 1929 and 1924 t ...

, and Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. ( Rozenfeld; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Kamenev was a leading figure in the early Soviet government and served as a Deputy Premier ...

, he began to rise in influence and prestige. In 1920, after the defeat of the Whites under Denikin, and the end of the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, he joined the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

.

Bolsheviks in power

Becoming a member of the nomenklatura he became a prosecutor in the new Soviet legal system, began a rivalry with a fellow lawyer, Nikolai Krylenko, and in 1925 was elected rector of Moscow University, which he began to clear of "unsuitable" students and professors. In 1928, he presided over the Shakhty Trial against 53 alleged counter-revolutionary "wreckers". Krylenko acted as prosecutor, and the outcome was never in doubt. As historian Arkady Vaksberg explains, "all the court's attention was concentrated not on analyzing the evidence, which simply did not exist, but on securing from the accused confirmation of their confessions of guilt that were contained in the records of the preliminary investigation." In November–December 1930, he presided as judge over the Industrial Party Trial, with Krylenko as prosecutor, which was accompanied by a storm of international protest. In this case, all eight defendants confessed their guilt. As a result, he was promoted. In April 1933, he was prosecutor in the Metro-Vickers trial, at which eight out of 18 defendants were British engineers, and which resulted in relatively light sentences. He carried out administrative preparations for a "systematic" drive "against harvest-wreckers and grain-thieves".Procurator General and Soviet law theorist

Vyshinsky was appointed First Deputy Procurator General of the Soviet Union when the office was first created on 30 June 1933. At this time, he outranked Krylenko but was nominally junior to Ivan Akulov. In January 1935, he prosecuted Grigory Zinoviev and 18 other former supporters of the Left Opposition, who were accused of 'moral responsibility' for the assassination ofSergei Kirov

Sergei Mironovich Kirov (born Kostrikov; 27 March 1886 – 1 December 1934) was a Russian and Soviet politician and Bolsheviks, Bolshevik revolutionary. Kirov was an early revolutionary in the Russian Empire and a member of the Bolshevik faction ...

.

In June 1935, Vyshinsky replaced Akulov, who had allegedly questioned the decision to link Zinoviev and others to the Kirov murder, and from thereon he was the legal mastermind of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

's Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

. Although he acted as a judge, he encouraged investigators to procure confessions from the accused. In some cases, he prepared the indictments before the "investigation" was concluded. In his ''Theory of Judicial Proofs in Soviet Justice'' ( Stalin Prize in 1947) he laid a theoretical base for the Soviet judicial system. He also used his own speeches from the Moscow Trials as an example of how defendants' statements could be used as primary evidence. Vyshinsky is cited for the principle that "confession of the accused is the queen of evidence".

Vyshinsky first became a nationally known public figure as a result of the Semenchuk case of 1936. Konstantin Semenchuk was the head of the Glavsevmorput station on Wrangel Island. He was accused of oppressing and starving the local Yupik and of ordering his subordinate, the sledge driver Stepan Startsev, to murder Dr. Nikolai Vulfson, who had attempted to stand up to Semenchuk, on 27 December 1934 (though there were also rumors that Startsev had fallen in love with Vulfson's wife, Dr. Gita Feldman, and killed him out of jealousy). The case came to trial before the Supreme Court of the RSFSR in May 1936; both defendants, attacked by Vyshinsky as "human waste", were found guilty and shot, and "the most publicised result of the trial was the joy of the liberated Eskimos."

In 1936, Vyshinsky achieved international infamy as the prosecutor at the Zinoviev-Kamenev trial (this trial had nine other defendants), the first of the Moscow Trials during the Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

, lashing its defenseless victims with vituperative rhetoric:Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartošek, Jean-Louis Panné, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Stéphane Courtois, ''The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression'', Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is an academic publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University. It is a member of the Association of University Presses. Its director since 2017 is George Andreou.

The pres ...

, 1999, , page 750

He often punctuated speeches with phrases like "Dogs of the Fascist bourgeoisie", "mad dogs of Trotskyism", "dregs of society", "decayed people", "terrorist thugs and degenerates", and "accursed vermin". This dehumanization aided in what historian Arkady Vaksberg calls "a hitherto unknown type of trial where there was not the slightest need for evidence: what evidence did you need when you were dealing with 'stinking carrion' and 'mad dogs'?"

He is also attributed by some as the author of an infamous quote from the Stalin era: "Give me a man and I will find the crime."

During the trials, Vyshinsky misappropriated the house and money of Leonid Serebryakov

Leonid Petrovich Serebryakov (; 11 June 1890 – 1 February 1937) was a Russian Soviet politician and Bolshevik who became a victim of the Great Purge.

Early life

Born at Samara, the son of a metalworker, Serebryakov left school at 14 to opera ...

(one of the defendants of the infamous Moscow Trials), who was later executed.

In April 1937, Vyshinsky denounced Yevgeny Pashukanis, the Soviet Union's foremost legal scholar and former Deputy People's Commissar for Justice as a 'wrecker'. This was the start of a purge of prosecutor's apparatus, carried out by Vyshinsky, which saw 90 per cent of provincial prosecutors removed, and many of them arrested. Pashukanis was executed later that year.

During the Great Purge, Vyshinsky was approached in his office by Mikhail Ishov, a military procurator based in West Siberia, who had been trying to stop the arrests of innocent people in that territory. Vyshinsky told him: "You have lost your sense of party and class. We don't intend to pat enemies on the head. ..If the enemy doesn't surrender, he must be destroyed." After the meeting, he reported Ishov, who was arrested and sentenced to five years in labour camps.

Roland Freisler, a German Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

judge, who served as the State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice, studied and had attended the trials by Vyshinsky's in 1938 to use a similar approach in show trials conducted by Nazi Germany.''Hitlers Helfer - Ronald Freisler der Hinrichter'' Roland Freisler, the Executioner">itler's Henchmen - Roland Freisler, the Executioner ZDF (1998), television documentary series, by Guido Knopp.Shirer, William, '' The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich'' (Touchstone Edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990)

In May 1939, Vyshinsky was promoted to the rank of Deputy Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars Ministers (ie deputy prime minister) of the Soviet Union. His sphere of responsibilities included education and culture, as these areas were incorporated more fully into the USSR, he directed efforts to convert the written alphabets of conquered peoples to the Cyrillic

The Cyrillic script ( ) is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic, Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Caucasian and Iranic-speaking countries in Southeastern Europe, Ea ...

alphabet., as well as the law.

In June 1939, he presided over the All-Union Conference of Stage Directors. The fourth speaker in the main debate, on 15 June, was Vsevolod Meyerhold, the Soviet Union's most renowned living stage director. His speech was not reported in the Soviet press, except to say that it was severely criticised. Meyerhold was arrested five days later, tortured, and shot.

Wartime diplomat

In June 1937, Vyshinsky took part in negotiations with the US Ambassador in Moscow, Joseph E. Davies, over trade debts, and after the completion of the last of the major show trials, in March 1938, he entered another phase in his career, devoted primarily to foreign affairs. Vyshinsky had a low opinion of diplomats because they often complained about the effect of trials on opinions in the West. TheGreat Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

inflicted tremendous losses on the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs. Maxim Litvinov was one of the few diplomats who survived and he was dismissed in 1939, and replaced by Vyacheslav Molotov.

In 1939, Vyshinsky introduced a motion to the Supreme Soviet to bring the Western Ukraine into the USSR.Vaksberg, ''Stalin's Prosecutor'', 204. In June to August 1940 he was sent to Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

to supervise the establishment of a pro-Soviet government and incorporation of that country into the USSR. He was generally well received, and he set out to purge the Latvian Communist Party of Trotskyists, Bukharinites, and possible foreign agents. In July 1940, a Latvian Soviet Republic was proclaimed. It was, unsurprisingly, granted admission to the USSR.

As a result of this success, on 6 September 1940, he was named First Deputy People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs, and taken into greater confidence by Stalin, Lavrentiy Beria, and Vyacheslav Molotov. His main responsibility was Eastern Europe, though he was the official that Stafford Cripps dealt with during his period as British Ambassador, and the one to whom Cripps passed on Winston Churchill's warning that Germany might be intending to invade the USSR, which Vyshinsky refused to discuss.

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union Vyshinsky was transferred to the shadow capital at Kuibyshev. He remained here for much of the war, but he continued to act as a loyal functionary, and attempted to ingratiate himself with Archibald Clark Kerr and visiting Republican presidential candidate Wendell Willkie. During the Tehran Conference in 1943, he remained in the Soviet Union to "keep shop" while most of the leadership was abroad. Stalin appointed him to the Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council (ACC) or Allied Control Authority (), also referred to as the Four Powers (), was the governing body of the Allies of World War II, Allied Allied-occupied Germany, occupation zones in Germany (1945–1949/1991) and Al ...

on Italian affairs where he began organizing the repatriation of Soviet POWs (including those who did not want to return to the Soviet Union). He also began to liaise with the Italian Communist Party in Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

.

In February 1945, he accompanied Stalin, Molotov, and Beria to the Yalta Conference. After returning to Moscow he was dispatched to Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, where he arranged for a communist regime to assume control in 1945. He then once again accompanied the Soviet leadership to the Potsdam Conference. On 26 February 1946, he rushed to Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

to force King Michael of Romania, whose palace was surrounded by Soviet tanks, to dismiss the anti-communist head of government, General Nicolae Rădescu and appoint the pro-communist Petru Groza

Petru Groza (7 December 1884 – 7 January 1958) was a Romanian politician, best known as the first Prime Minister of Romania, Prime Minister of the Romanian Communist Party, Communist Party-dominated government under Soviet Union, Soviet Sovie ...

.

British diplomat Sir Frank Roberts, who served as British chargé d'affaires in Moscow from February 1945 to October 1947, described him as follows:

Post-Second World War

He was responsible for the Soviet preparations for the trial of the major German war criminals by the International Military Tribunal.

In 1953, he was among the chief figures accused by the U.S. Congress Kersten Committee during its investigation of the Soviet

He was responsible for the Soviet preparations for the trial of the major German war criminals by the International Military Tribunal.

In 1953, he was among the chief figures accused by the U.S. Congress Kersten Committee during its investigation of the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states

The occupation of the Baltic states was a period of annexation of

Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania by the Soviet Union from 1940 until its Dissolution of the Soviet Union, dissolution in 1991. For a period of several years during World War II, Naz ...

.

The positions he held included those of vice-premier (1939–1944), Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs (1940–1949), Minister of Foreign Affairs

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and foreign relations, relations, diplomacy, bilateralism, ...

(1949–1953), academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union from 1939, and permanent representative of the Soviet Union to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

.

Death

Vyshinsky died on 22 November 1954 inNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

. His body was returned to Moscow by a special flight, and his ashes buried at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis.

Scholarship

Vyshinsky was the director of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union's Institute of State and Law. Until the period ofde-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

, the Institute of State and Law was named in his honor.

During his tenure as director of the ISL, Vyshinsky oversaw the publication of several important monographs on the general theory of state and law.

Family

Vyshinsky married Kapitolina Isidorovna Mikhailova and had a daughter named Zinaida Andreyevna Vyshinskaya (born 1909).Awards and decorations

* Six Orders of Lenin (1937, 1943, 1945, 1947, 1954) * Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1933) * Medal "For the Defence of Moscow" (1944) * Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1945). * Stalin Prize, first class (1947; for the monograph "Theory of forensic evidence in Soviet law")Cultural references

ThePet Shop Boys

Pet Shop Boys are an English synth-pop duo formed in London in 1981. Consisting of vocalist Neil Tennant and keyboardist Chris Lowe, they have sold more than 100 million records worldwide and were listed as the most successful duo in UK music h ...

song "This Must Be the Place I Waited Years to Leave" from the album ''Behaviour

Behavior (American English) or behaviour (British English) is the range of actions of Individual, individuals, organisms, systems or Artificial intelligence, artificial entities in some environment. These systems can include other systems or or ...

'' (1990) contains a sample of recording from Vyshinsky's speech at the Zinoviev-Kamenev trial of 1936.

Vyshinsky appears at the beginning of the 2016 novel ''A Gentleman in Moscow'' by Amor Towles as the prosecutor in a purported transcript of an appearance by Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, the novel's gentleman protagonist, before the Emergency Committee of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs on 21 June 1922.

In Gregor Martov's alternative history novel ''His New Majesty'',Published in Russian 1997, English and German translation 2002 depicting an alternate history in which Anton Denikin's White forces defeated the Bolsheviks in 1921, Vyshinsky joins the winners and acts as the royal prosecutor in a show trial in which Lenin, Stalin, Trotsky and Bukharin are sentenced to death as "Subversives, Traitors, Blasphemers and Regicides". He is rewarded in being ennobled by the restored czar and made a duke, but gets assassinated by an anarchist girl with whom he had a secret affair.

The saying " give me the man; there'll be a paragraph for him", popular in Poland and referring to the miscarriage of justice under the communist regimes, has been attributed to him.

See also

* Foreign relations of the Soviet UnionReferences

External links

"The Soviet Legal Narrative" - An essay by Anna Lukina about Vyshinsky as a theorist and his influence on the Nuremberg Trials and international law

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20060619201454/http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hiss/hissvenona.html Venona transcript #1822* {{DEFAULTSORT:Vyshinsky, Andrey 1883 births 1954 deaths 20th-century jurists 20th-century Russian politicians Politicians from Odesa People from Kherson Governorate Deputy heads of government of the Soviet Union Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union members Permanent representatives of the Soviet Union to the United Nations Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary (Soviet Union) Candidates of the Presidium of the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Members of the Central Committee of the 18th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Full Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Academic staff of Moscow State University Academic staff of the Plekhanov Russian University of Economics Rectors of Moscow State University Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Bolsheviks Mensheviks Ministers of foreign affairs of the Soviet Union First convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Second convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Fourth convocation members of the Soviet of the Union Recipients of the Stalin Prize Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour Great Purge perpetrators Trial of the Sixteen (Great Purge) Lawyers from the Russian Empire People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent Soviet people of Polish descent Ukrainian people of Polish descent Russian prosecutors Russian revolutionaries Soviet lawyers Burials at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis Jurisprudence academics