Andrei Bubnov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

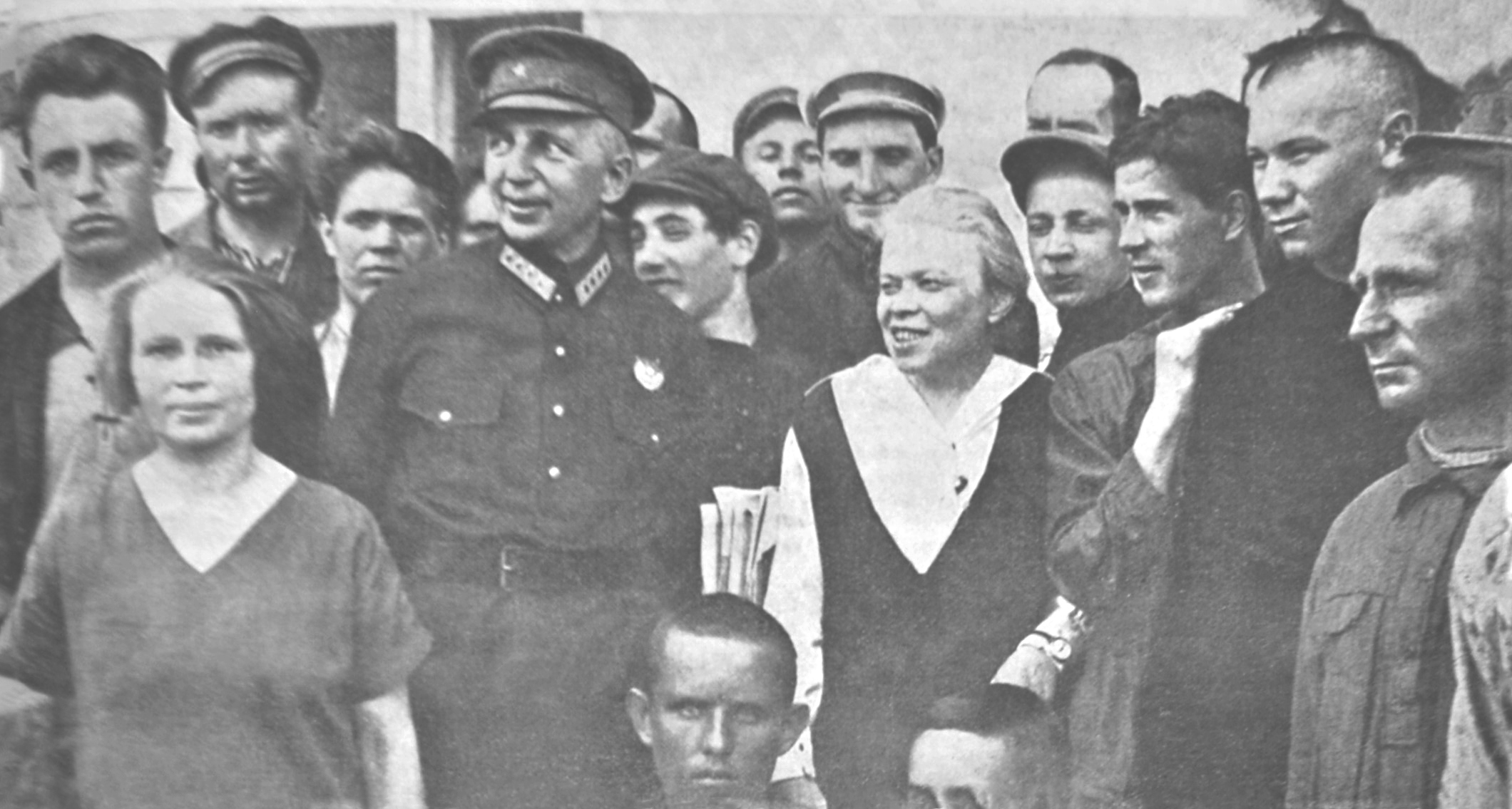

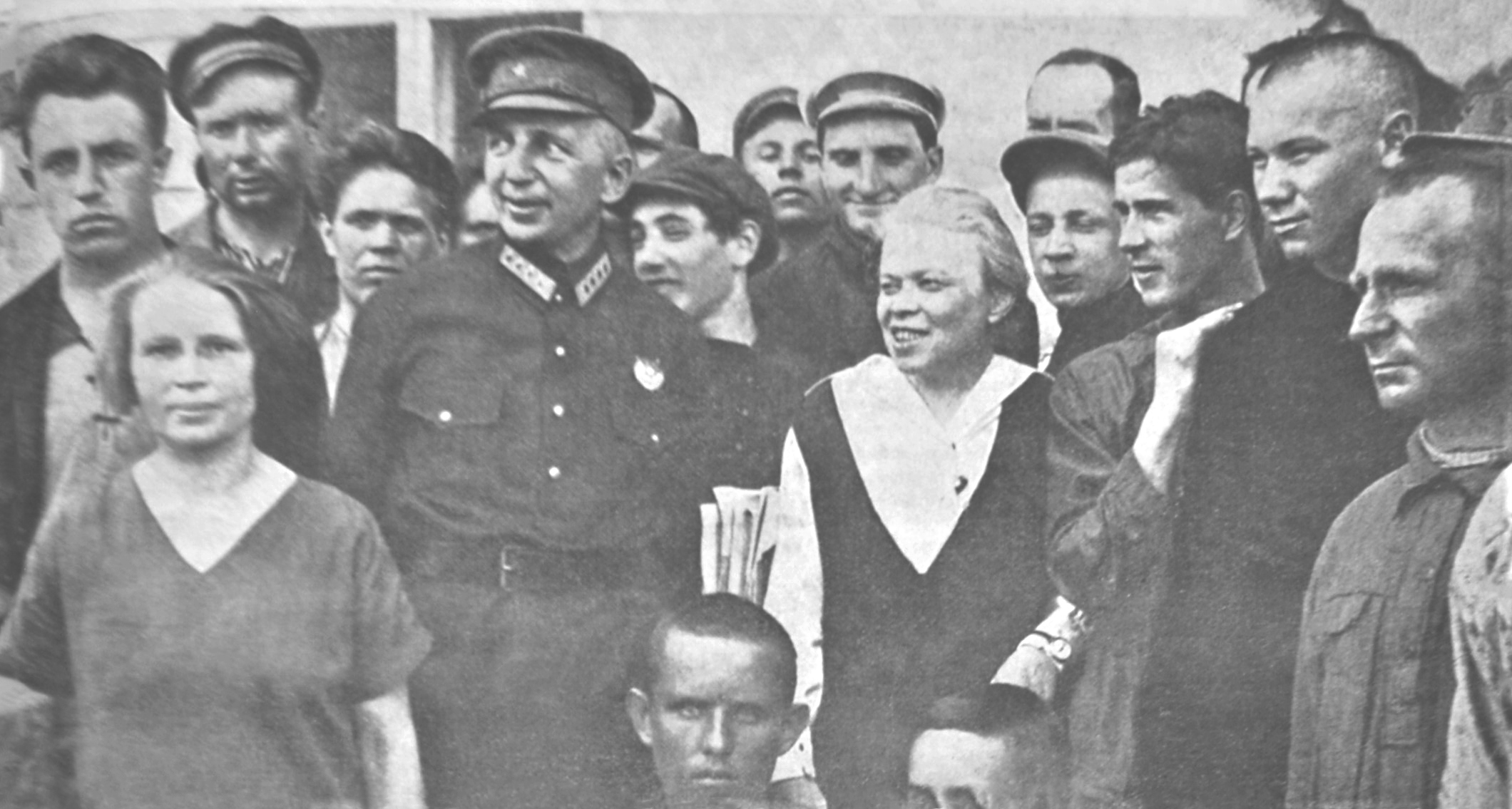

Andrei Sergeyevich Bubnov (; – 1 August 1938) was a Russian

On his release from prison in 1909 Bubnov was made an agent of the Central Committee in Moscow. He was arrested again in 1910, and interned in a fortress. After his release in 1911, he was sent to organize workers in

On his release from prison in 1909 Bubnov was made an agent of the Central Committee in Moscow. He was arrested again in 1910, and interned in a fortress. After his release in 1911, he was sent to organize workers in

Early in 1926, Bubnov was appointed head of a Soviet delegation to China, to investigate what seemed to be a breakdown in relations with the Chinese military authorities. He travelled under the name Ivanovsky, taking extraordinary precautions to hide his identity. Following the

Early in 1926, Bubnov was appointed head of a Soviet delegation to China, to investigate what seemed to be a breakdown in relations with the Chinese military authorities. He travelled under the name Ivanovsky, taking extraordinary precautions to hide his identity. Following the

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

revolutionary leader, Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

politician and military leader, member of the Left Opposition

The Left Opposition () was a faction within the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1923 to 1927 headed '' de facto'' by Leon Trotsky. It was formed by Trotsky to mount a struggle against the perceived bureaucratic degeneration within th ...

, and an important Bolshevik figure in Ukraine.

Life

Early career

Bubnov was born in Ivanovo-Voznesensk in Vladimir Governorate (nowIvanovo

Ivanovo (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city in Russia and the administrative center and largest city of Ivanovo Oblast, located northeast of Moscow and approximately from Yaroslavl, Vladimir, Russia, Vladimir and Kostroma. ...

, Ivanovo Oblast

Ivanovo Oblast () is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast). It had a population of 927,828 as of the Russian Census (2021), 2021 Russian Census.

Its three largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, cities are Ivanovo (the administrat ...

, Russia) into a local Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

merchant's family. He studied at the Moscow Agricultural Institute, where he was involved in revolutionary circles beginning in 1900. He failed to graduate from the institute. In 1903, he joined the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

wing of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

(RSDLP). In summer 1905, he joined the regional party committee of Ivanono-Voznesensk, and was their delegate to the 4th (1906) and 5th (1907) Party Conferences in Stockholm and London. Between 1907 and 1908, he was a member of the RSDLP's Moscow committee, and of the Bolshevik committee for the Central Industrial Region. He was arrested in 1908. In his autobiography, he stated that he was arrested 13 times during his revolutionary career, and spent four years imprisoned for his political activities.

On his release from prison in 1909 Bubnov was made an agent of the Central Committee in Moscow. He was arrested again in 1910, and interned in a fortress. After his release in 1911, he was sent to organize workers in

On his release from prison in 1909 Bubnov was made an agent of the Central Committee in Moscow. He was arrested again in 1910, and interned in a fortress. After his release in 1911, he was sent to organize workers in Nizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod ( ; rus, links=no, Нижний Новгород, a=Ru-Nizhny Novgorod.ogg, p=ˈnʲiʐnʲɪj ˈnovɡərət, t=Lower Newtown; colloquially shortened to Nizhny) is a city and the administrative centre of Nizhny Novgorod Oblast an ...

. From there, he was one of the organisers of the Prague Conference

The Prague Conference, officially the 6th All-Russian Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, was held in Prague, Austria-Hungary (Present-Day Czechia), on 5–17 January 1912. Sixteen Bolsheviks and two Mensheviks attended, alt ...

of January 1912, the first that excluded all RSDLP members who were not Bolsheviks. He was under arrest at the time of the conference, but in his absence was elected a candidate member of the first all-Bolshevik Central Committee. Afterwards he was sent to St Petersburg to assist in the launch of ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'', and to work with the Bolshevik faction in the Fourth Duma. Arrested yet again, he was deported to Kharkov

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

.

In the Russian Revolution and Civil War

On the outbreak of theFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

Bubnov became involved in the anti-war movement

An anti-war movement is a social movement in opposition to one or more nations' decision to start or carry on an armed conflict. The term ''anti-war'' can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during con ...

in Kharkiv

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

, whence he had been deported after being expelled from St Petersburg. Arrested in August 1914, he was deported to Poltava

Poltava (, ; , ) is a city located on the Vorskla, Vorskla River in Central Ukraine, Central Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Poltava Oblast as well as Poltava Raion within the oblast. It also hosts the administration of Po ...

. He moved to Samara

Samara, formerly known as Kuybyshev (1935–1991), is the largest city and administrative centre of Samara Oblast in Russia. The city is located at the confluence of the Volga and the Samara (Volga), Samara rivers, with a population of over 1.14 ...

, where he was arrested in October 1916, and exiled to Siberia in February 1917, but while he was in transit, he heard news of the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

, and made his way back to Moscow.

In Moscow, Bubnov was elected to the Moscow Soviet and, at the 6th Party Conference in July 1917, he was elected to the Bolshevik central committee, which would later become the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the Central committee, highest organ of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) between Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Congresses. Elected by the ...

. In August, he moved to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

, where he was a central figure during the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

. On 23 October, two weeks before the revolution, the Central Committee appointed a seven-man political council consisting of Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, Zinoviev, Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. ( Rozenfeld; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Kamenev was a leading figure in the early Soviet government and served as a Deputy Premier ...

, Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

, Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, Sokolnikov and Bubnov. This is sometimes regarded as the first Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

, but Trotsky's recollection was that this group was "completely impractical", since Lenin and Zinoviev were in hiding, and Zinoviev and Kamenev opposed the planned revolution, and "never once assembled." Bubnov's real importance was as a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee

The Military Revolutionary Committee (Milrevcom; , ) was the name for military organs created by the Bolsheviks under the soviets in preparation for the October Revolution (October 1917 – March 1918).

. "It was this body rather than the party 'politburo' which made the military preparations for the revolution." Together, they directed the inner-workings of would become known as the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

. His role was to supervise the seizure of the postal and telegraph systems. After the successful execution of the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, he was appointed Commissar for Railways, before being sent to Rostov-on-Don

Rostov-on-Don is a port city and the administrative centre of Rostov Oblast and the Southern Federal District of Russia. It lies in the southeastern part of the East European Plain on the Don River, from the Sea of Azov, directly north of t ...

to organise resistance to the newly formed White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

of General Kaledin.

Bubnov clashed with Lenin for the first time when he opposed the decision to sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

that ended the war with Germany. For the next four years, Bubnov was prominent in the left wing opposition to Lenin. He was dropped from the Central Committee in March 1918, but reinstated as a candidate member a year later. In February 1918, he joined the Left Communists, and moved to Ukraine, to organise partisan detachments in the 'neutral zone' east of the German front line. He and Georgy Pyatakov

Georgy Leonidovich Pyatakov (; ; 6 August 1890 – 30 January 1937) was a Ukrainian revolutionary and Soviet politician. He was a leading Bolshevik in Ukraine during and after the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Born in Kiev Governorate, Pyatakov wa ...

, who led the left in the Ukrainian party, argued that Ukraine was not a signatory to the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, and that they were therefore entitled to organise partisan war against the Germans.

In October 1918, Bubnov moved to Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, which was ruled by Hetman Skoropadskiy, with German backing, and later by the Ukrainian nationalist Symon Petliura. Bubnov acted as the chairman of the clandestine Kyiv soviet, retaining that position after the Red Army had taken Kyiv. During the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, he was a political commissar with the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

, fighting on the Ukrainian Front. During the Ninth Party Congress in Moscow, in March 1920, he accused the central party leadership of wrecking the party organisation in Ukraine by removing oppositionists, and threatening the stability of the Ukraine government by alienating peasant farmers. He was again removed from the Central Committee and, soon afterwards, he was recalled to Moscow to take charge of the textile industry. At the next party congress, in March 1921, he acted as a spokesman for the " Democratic Centralists", who demanded less centralised control of the communist party, but on hearing of the outbreak of the Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion () was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors, Marines, naval infantry, and civilians against the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik government in the Russian port city of Kronstadt. Located on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland, ...

, rushed north to take part in suppresing, for which he was awarded the Order of the Red Banner.

In 1921–22, Bubnov was posted in the North Caucasus

The North Caucasus, or Ciscaucasia, is a subregion in Eastern Europe governed by Russia. It constitutes the northern part of the wider Caucasus region, which separates Europe and Asia. The North Caucasus is bordered by the Sea of Azov and the B ...

. In 1922, he was appointed head of the Agitprop

Agitprop (; from , portmanteau of ''agitatsiya'', "agitation" and ''propaganda'', "propaganda") refers to an intentional, vigorous promulgation of ideas. The term originated in the Soviet Union where it referred to popular media, such as literatu ...

department of the Central Committee, which meant he was working alongside Stalin, the new General Secretary.

In the Soviet Union

Bubnov's last act as an oppositionist was to sign the Declaration of 46 in October 1923, which was a call for greater party democracy. The Declaration was organised and penned by future members of theLeft Opposition

The Left Opposition () was a faction within the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1923 to 1927 headed '' de facto'' by Leon Trotsky. It was formed by Trotsky to mount a struggle against the perceived bureaucratic degeneration within th ...

, who supported Trotsky in the power struggle that followed Lenin's death. In January 1924, while Lenin was incapacitated by a stroke, the head of the Political Directorate, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko

Vladimir Alexandrovich Antonov-Ovseenko (; ; 9 March 1883 – 10 February 1938), real surname Ovseenko, party aliases 'Bayonet' () and 'Nikita' (), literary pseudonym A. Galsky (), was a prominent Bolshevik leader, Soviet statesman, mili ...

, an ardent Trotsky supporter, was sacked. Bubnov was appointed in his place, despite his past as a left oppositionist. From then on, he was a reliable supporter of Stalin. In May 1924, he was restored to full membership of the Central Committee, which he retained until his arrest. In 1924–29, he was a member of the Orgburo

The Orgburo (), also known as the Organisational Bureau (), of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union existed from 1919 to 1952, when it was abolished at the 19th Congress of the Communist Party and its functions wer ...

.

Early in 1926, Bubnov was appointed head of a Soviet delegation to China, to investigate what seemed to be a breakdown in relations with the Chinese military authorities. He travelled under the name Ivanovsky, taking extraordinary precautions to hide his identity. Following the

Early in 1926, Bubnov was appointed head of a Soviet delegation to China, to investigate what seemed to be a breakdown in relations with the Chinese military authorities. He travelled under the name Ivanovsky, taking extraordinary precautions to hide his identity. Following the Canton Coup

The Canton Coup of 20 March 1926, also known as the or the was a purge of Communist elements of the Nationalist army in Guangzhou (then romanized as "Canton") undertaken by Chiang Kai-shek. The incident solidified Chiang's power immedi ...

on 20 March 1926, he worked out an agreement with the new Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek. He then worked with Grigori Voitinsky and Fedor Raskolnikov on the "Preliminary Theses on the Situation in China", which was presented to the ECCI in November and December of that year.

In 1929, he replaced Lunacharsky as People's Commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English language, English transliteration of the Russian language, Russian (''komissar''), which means 'commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the pol ...

for Education. As Commissar for Education, he ended the period of progressive, experimental educational practices and switched the emphasis to training in practical industrial skills. It was in this capacity that he attended the First All-Russian Museum Congress held in Moscow in December 1930.

Arrest and death

In October 1937, during theGreat Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

, Bubnov arrived at the Kremlin for a meeting of the Central Committee, but was barred by the guards from entering. Frightened, he went back to the Commissariat for Education, and heard on the radio that evening that he had been removed from his post of People's Commissar. He was arrested by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

a few days later, on 17 October 1937. He was then still a member of the Central Committee, which convened on 4 December, and received a message from Stalin saying that Bubnov had confessed to being 'an enemy of the people' and a German spy. He was expelled from the Party Central Committee.

Though the charges were false, Bubnov did confess quite quickly and probably under torture. In fact, he became so co-operative that the NKVD put him in the same cell as Pavel Postyshev

Pavel Petrovich Postyshev (; – 26 February 1939) was a Soviet politician, state and Communist Party official and party publicist. He was a member of Joseph Stalin's inner circle, before falling victim to the Great Purge.

In 2010, a court in K ...

, who was refusing to incriminate himself, in the hope that Bubnov would help break his resolve. On 26 July, Bubnov's name was included in a death list of 138 individuals submitted to Stalin, who ordered them all to be shot. After a 20 minute trial on 1 August 1938, he was sentenced to death, and shot the same day.

The modus operandi

A (often shortened to M.O. or MO) is an individual's habits of working, particularly in the context of business or criminal investigations, but also generally. It is a Latin phrase, approximately translated as .

Term

The term is often used in ...

of the Soviet regime was often to keep secret the fate of particular purged persons: whether they were sent to internal exile to a labor camp, sent to a psychiatric hospital (in which the regime disguised confinement and drugging as compassionate "health care"), or executed. This policy encouraged their families and the general public to believe that they were probably still alive in a camp or hospital somewhere.

Bubnov was posthumously rehabilitated in March 1956 during the de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

of the Khrushchev thaw

The Khrushchev Thaw (, or simply ''ottepel'')William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era, London: Free Press, 2004 is the period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s when Political repression in the Soviet Union, repression and Censorship in ...

. The Soviet government did not make public the lists of the purged persons who had already long been executed. Thus, their relatives were often still searching for them in various psychiatric hospitals in the 1970s, as was the case with Bubnov. Notes

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bubnov, Andrei Sergeyevich 1883 births 1938 deaths People from Ivanovo People from Shuysky Uyezd Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Mayors of Kyiv Members of the Orgburo of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Orgburo of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Orgburo of the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Orgburo of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Secretariat of the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Central Committee of the 6th Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Central Committee of the 7th Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 6th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Central Committee of the 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Central Committee of the 11th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Central Committee of the 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Head of Propaganda Department of CPSU CC Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) members Group of Democratic Centralism Left communists Left Opposition People's commissars and ministers of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic Soviet propagandists Chiefs of the Main Political Directorate of the Soviet Army and Soviet Navy Russian exiles in the Russian Empire People of the Russian Civil War Great Purge victims from Russia Russian anti-capitalists Soviet rehabilitations Military Opposition