Ancient History Of Yemen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ancient history of

The ancient history of

In the first half of the 19th century other European travelers brought back over one hundred inscriptions. This stage of investigation reached its climax with the travels of the Frenchman Joseph Halévy 1869/70 and the Austrian Eduard Glaser 1882–1894, who together either copied or brought back to Europe some 2500 inscriptions. On the basis of this epigraphical material Glaser and

In the first half of the 19th century other European travelers brought back over one hundred inscriptions. This stage of investigation reached its climax with the travels of the Frenchman Joseph Halévy 1869/70 and the Austrian Eduard Glaser 1882–1894, who together either copied or brought back to Europe some 2500 inscriptions. On the basis of this epigraphical material Glaser and

The first known inscriptions of Ḥaḑramawt are known from the 8th century BCE. It was first referenced by an outside civilization in an Old Sabaic inscription of Karab'il Watar from the early 7th century BCE, in which the King of Ḥaḑramawtt, Yada'il, is mentioned as being one of his allies. When the Minaeans took control of the caravan routes in the 4th century BCE, however, Ḥaḑramawt became one of its confederates, probably because of commercial interests. It later became independent and was invaded by the growing kingdom of Ḥimyar toward the end of the 1st century BCE, but it was able to repel the attack. Ḥaḑramawt annexed Qatabān in the second half of the 2nd century CE, reaching its greatest size. During this period, Ḥaḑramawt was continuously at war with Himyar and Saba', and the Sabaean king Sha'irum Awtar was even able to take its capital, Shabwah, in 225. During this period the

The first known inscriptions of Ḥaḑramawt are known from the 8th century BCE. It was first referenced by an outside civilization in an Old Sabaic inscription of Karab'il Watar from the early 7th century BCE, in which the King of Ḥaḑramawtt, Yada'il, is mentioned as being one of his allies. When the Minaeans took control of the caravan routes in the 4th century BCE, however, Ḥaḑramawt became one of its confederates, probably because of commercial interests. It later became independent and was invaded by the growing kingdom of Ḥimyar toward the end of the 1st century BCE, but it was able to repel the attack. Ḥaḑramawt annexed Qatabān in the second half of the 2nd century CE, reaching its greatest size. During this period, Ḥaḑramawt was continuously at war with Himyar and Saba', and the Sabaean king Sha'irum Awtar was even able to take its capital, Shabwah, in 225. During this period the

The Ḥimyarites eventually united Southwestern Arabia, controlling the Red Sea as well as the coasts of the Gulf of Aden. From their capital city, the Ḥimyarite kings launched successful military campaigns, and had stretched its domain at times as far east to the Persian Gulf and as far north as the Arabian Desert.

During the 3rd century CE, the South Arabian kingdoms were in continuous conflict with one another. GDRT of Aksum began to interfere in South Arabian affairs, signing an alliance with Saba', and a Ḥimyarite text notes that Ḥaḑramawt and Qatabān were also all allied against the kingdom. As a result of this, the Kingdom of Aksum was able to capture the Ḥimyarite capital of Ẓifār in the first quarter of the 3rd century. However, the alliances did not last, and Sha'ir Awtar of Saba' unexpectedly turned on Ḥadramawt, allying again with Aksum and taking its capital in 225. Ḥimyar then allied with Saba' and invaded the newly taken Aksumite territories, retaking Ẓifār, which had been under the control of GDRT's son BYGT, and pushing Aksum back into the Tihāmah.

They established their capital at Thifar (now just a small village in the Ibb region) and gradually absorbed the Sabaean kingdom. They traded from the port of Mawza'a on the Red Sea. Dhū Nuwās, a Ḥimyarite king, changed the state religion to

The Ḥimyarites eventually united Southwestern Arabia, controlling the Red Sea as well as the coasts of the Gulf of Aden. From their capital city, the Ḥimyarite kings launched successful military campaigns, and had stretched its domain at times as far east to the Persian Gulf and as far north as the Arabian Desert.

During the 3rd century CE, the South Arabian kingdoms were in continuous conflict with one another. GDRT of Aksum began to interfere in South Arabian affairs, signing an alliance with Saba', and a Ḥimyarite text notes that Ḥaḑramawt and Qatabān were also all allied against the kingdom. As a result of this, the Kingdom of Aksum was able to capture the Ḥimyarite capital of Ẓifār in the first quarter of the 3rd century. However, the alliances did not last, and Sha'ir Awtar of Saba' unexpectedly turned on Ḥadramawt, allying again with Aksum and taking its capital in 225. Ḥimyar then allied with Saba' and invaded the newly taken Aksumite territories, retaking Ẓifār, which had been under the control of GDRT's son BYGT, and pushing Aksum back into the Tihāmah.

They established their capital at Thifar (now just a small village in the Ibb region) and gradually absorbed the Sabaean kingdom. They traded from the port of Mawza'a on the Red Sea. Dhū Nuwās, a Ḥimyarite king, changed the state religion to

A Dam at Marib

Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions

Università degli studi di Pisa. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ancient History Of Yemen

The ancient history of

The ancient history of Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

or South Arabia

South Arabia (), or Greater Yemen, is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it has also historically included Najran, Jazan, ...

is especially important because it is one of the oldest centers of civilization

A civilization (also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society characterized by the development of state (polity), the state, social stratification, urban area, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyon ...

in the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

. Its relatively fertile land and adequate rainfall in a moister climate helped sustain a stable population, a feature recognized by the ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, who described Yemen as ''Eudaimon Arabia'' (better known in its Latin translation, ''Arabia Felix'') meaning ''Fortunate Arabia'' or ''Happy Arabia''. Between the eighth century BCE and the sixth century CE, it was dominated by six main states which rivaled each other, or were allied with each other and controlled the lucrative spice trade

The spice trade involved historical civilizations in Asia, Northeast Africa and Europe. Spices, such as cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, pepper, nutmeg, star anise, clove, and turmeric, were known and used in antiquity and traded in t ...

: Saba', Ma'īn, Qatabān, Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah and Mahrah, Dhofar in southwestern Oman, and Sharurah in the Najran Province of Saudi A ...

, Kingdom of Awsan, and the Himyarite Kingdom

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qataban, Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According ...

. Islam arrived in 630 CE and Yemen became part of the Muslim realm.

The centers of the Old South Arabian kingdoms of present-day Yemen lay around the desert area called Ramlat al-Sab'atayn

Yemeni Desert.

The Ramlat al-Sab'atayn () is a desert region that corresponds with the northern deserts of modern Yemen ( Al-Jawf, Marib, Shabwah governorates) and southwestern Saudi Arabia (Najran province).

It comprises mainly transverse and s ...

, known to medieval Arab geographers as Ṣayhad. The southern and western Highlands and the coastal region were less influential politically. The coastal cities were however already very important from the beginning for trade. Apart from the territory of modern Yemen, the kingdoms extended into Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

, as far as the north Arabian oasis of Lihyan

Lihyan (, ''Liḥyān''; Greek: Lechienoi), also called Dadān or Dedan, was an ancient Arab kingdom that played a vital cultural and economic role in the north-western region of the Arabian Peninsula and used Dadanitic language. The kingdom fl ...

(also called Dedan), to Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

, and even along coastal East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

to what is now Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

.

Archaeology of Yemen

Sabaean Studies, the study of the cultures of Ancient South Arabia, belong to the younger branches of archaeology since in Europe ancient South Arabia remained unknown for much longer than other regions of the Orient. In 1504 a European, namely the Italian Lodovico di Varthema, first managed to venture into the interior. Two Danish expeditions contributed to by Johann David Michaelis (1717–1791) andCarsten Niebuhr

Carsten Niebuhr, or Karsten Niebuhr (17 March 1733 Cuxhaven, Lüdingworth – 26 April 1815 Meldorf, Dithmarschen), was a German mathematician, Cartography, cartographer, and Geographical exploration, explorer in the service of Denmark-Norway. He ...

(1733–1815) among others, contributed to scientific study, if only in a modest way.

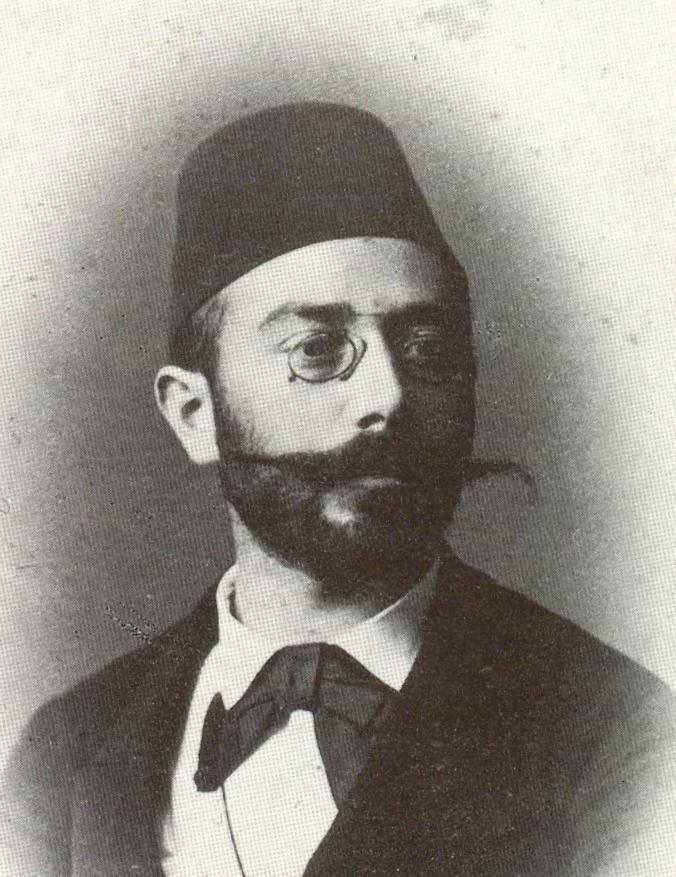

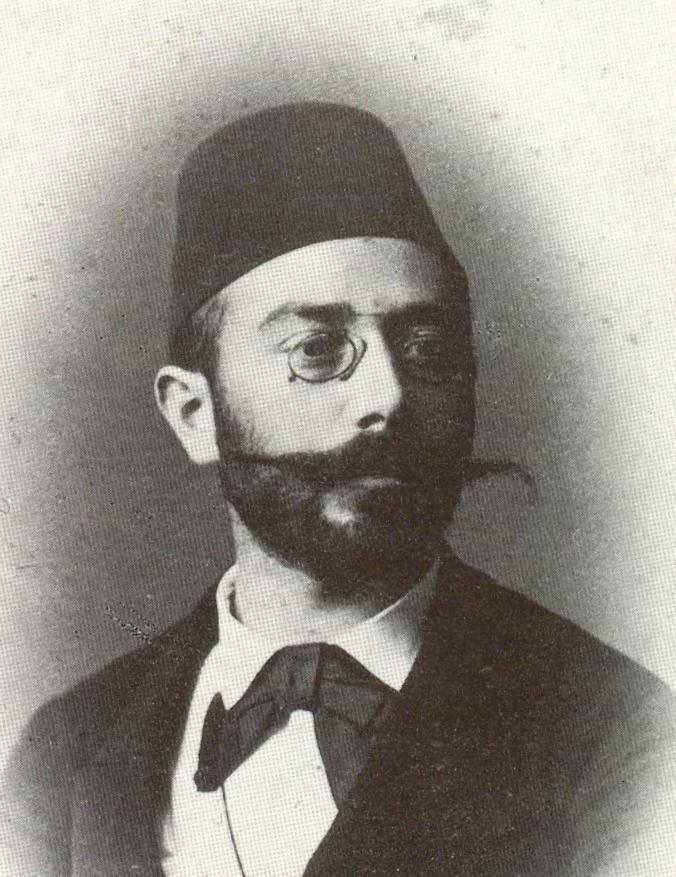

In the first half of the 19th century other European travelers brought back over one hundred inscriptions. This stage of investigation reached its climax with the travels of the Frenchman Joseph Halévy 1869/70 and the Austrian Eduard Glaser 1882–1894, who together either copied or brought back to Europe some 2500 inscriptions. On the basis of this epigraphical material Glaser and

In the first half of the 19th century other European travelers brought back over one hundred inscriptions. This stage of investigation reached its climax with the travels of the Frenchman Joseph Halévy 1869/70 and the Austrian Eduard Glaser 1882–1894, who together either copied or brought back to Europe some 2500 inscriptions. On the basis of this epigraphical material Glaser and Fritz Hommel

Fritz Hommel (31 July 1854 – 17 April 1936) was a German Orientalist.

Biography

Hommel was born on 31 July 1854 in Ansbach. He studied in Leipzig and was habilitated in 1877 in Munich, where in 1885, he became an extraordinary professor ...

especially began to analyse the Old South Arabian language and history. After the First World War excavations were finally carried out in Yemen. From 1926 Syrians and Egyptians also took part in the research into ancient South Arabia. The Second World War brought in a new phase of scientific preoccupation with ancient Yemen: in 1950–1952 the American Foundation for the Study of Man, founded by Wendell Phillips, undertook large-scale excavations in Timna and Ma'rib, in which William Foxwell Albright and Fr. Albert Jamme, who published the corpus of inscriptions, were involved. From 1959 Gerald Lankester Harding began the first systematic inventories of the archaeological objects in the then British Protectorate of Aden. At this time Hermann von Wissmann was particularly involved with the study of the history and geography of ancient South Arabia. In addition, the French excavations of 1975–1987 in Shabwah and in other locations, the Italian investigations of Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

remains and the work of the German Archaeological Institute

The German Archaeological Institute (, ''DAI'') is a research institute in the field of archaeology (and other related fields). The DAI is a "federal agency" under the Federal Foreign Office, Federal Foreign Office of Germany.

Status, tasks and ...

in the Ma'rib area are particularly noteworthy.

Written sources

The body of source material for Old South Arabia is sparse. Apart from a few mentions in Assyrian, Persian, Roman and Arabic sources, as well as in the Old Testament, which date back to the 8th century BCE right up to the Islamic period, the Old South Arabian inscriptions are the main source. These are however largely very short and as a result limited in the information they provide. The predominant part of the inscriptions originates from Saba' and from the Sabaeo-Himyaritic Kingdom which succeeded it, the least come from Awsān, which only existed as an independent state for a short time. Most of the extant texts are building inscriptions or dedications; it is rare for historical texts to be found.Chronology

Although the Kingdom of Saba' already appears inAssyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

n sources in the 8th century BCE, this benchmark is not sufficient to date the early history of ancient South Arabia, because the first absolutely reliable dating starts with the military campaign of Aelius Gallus in 25 BCE, and the mention of the king Ilasaros. For earlier times the chronology must be established on the basis of a comparison of the Old South Arabian finds with those from other regions, through palaeography

Palaeography (American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, UK) or paleography (American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, US) (ultimately from , , 'old', and , , 'to write') is the study and academic disciplin ...

, on the basis of the reconstructed sequence of kings and by radio carbon dating. Here two schools of thought have essentially evolved: the "Short Chronology" and the "Long Chronology". At the end of the 19th century Eduard Glaser and Fritz Hommel

Fritz Hommel (31 July 1854 – 17 April 1936) was a German Orientalist.

Biography

Hommel was born on 31 July 1854 in Ansbach. He studied in Leipzig and was habilitated in 1877 in Munich, where in 1885, he became an extraordinary professor ...

dated the beginning of the Old South Arabian Civilisation to the late 2nd millennium BCE, a dating that persisted for many years.

In 1955 Jacqueline Pirenne published a comparison of Old South Arabian and Greek art and came to the conclusion that the South Arabian Civilisation first developed in the 5th century BCE under Greek influence. She also supported this new "Short Chronology" by means of paleaeographic analysis of the forms Old South Arabian letters. Based on the American excavations in Timna and Ma'rib in 1951–52 another "Intermediary Chronology" came into being at about the same time, which merely set the beginning of Qatabān and Ma'īn at a later time than in the "Long Chronology". On the basis of the study of a rock inscription at Ma'rib ("Glaser 1703") A. G. Lundin and Hermann von Wissmann dated the beginning of Saba' back into the 12th or the 8th century BCE. Although their interpretation was later demonstrated to be partially incorrect, the "Short Chronology" has not been definitively proven, and in more recent times more arguments have been brought against it. Above all because of the results of new archaeological research, such as that carried out by the Italians in Yala / Hafari and by the French in Shabwah the "Long Chronology" attracts more and more supporters. Meanwhile, the majority of experts in Sabaean studies adhere to Wissman's Long Chronology, which is why the dates in this article have been adjusted in accordance with it.

Islamic accounts of pre-dynastic Qahṭān (3rd millennium BCE - 8th century BCE)

According to medieval Muslim Arab historians,ancient Semitic-speaking peoples

Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples or Proto-Semitic people were speakers of Semitic languages who lived throughout the ancient Near East and North Africa, including the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Arabian Peninsula and Carthage from the 3rd millenniu ...

of South Arabia united as the Qahtanites

The Qahtanites (; ), also known as Banu Qahtan () or by their nickname ''al-Arab al-Ariba'' (), are the Arabs who originate from modern-day Yemen. The term "Qahtan" is mentioned in multiple Ancient South Arabian script, Ancient South Arabian ins ...

. The Qahṭānites began building simple earth dams and canals in the Marib area in the Ramlat al-Sab'atayn. This area would later become the site of the Marib Dam.

A trade route began to flourish along the Red Sea coasts of Tihāmah. This period witnessed the reign of the legendary Queen of Sheba

The Queen of Sheba, also known as Bilqis in Arabic and as Makeda in Geʽez, is a figure first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. In the original story, she brings a caravan of valuable gifts for Solomon, the fourth King of Israel and Judah. This a ...

mentioned in the Bible, called ''Bilqīs'' by Muslim scholars.

At the end of this period, in the 9th century BCE, writing was introduced; this now meant that South Arabian history could be written down.

Archaeology and the prehistory of Yemen

The study of South Arabian prehistory is still at the beginning, although sites are known going back to thePalaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

. There are tumuli

A tumulus (: tumuli) is a mound of Soil, earth and Rock (geology), stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds, mounds, howes, or in Siberia and Central Asia as ''kurgans'', and may be found through ...

and megalithic

A megalith is a large Rock (geology), stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. More than 35,000 megalithic structures have been identified across Europe, ranging ...

enclosures dating back to the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

. Immediately before the historical kingdoms in 2500, two Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

cultures go out of North Yemen and from the coast of the Indian Ocean. In the middle of the second millennium BCE, the first important urban centers appear in the coastal area, among which are the sites of Sabir and Ma'laybah. So far, it has not been adequately explained whether the Old South Arabian Civilization of Yemen was a direct continuation from the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, or if at the beginning of the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

groups of people began wandering south from Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

or North Arabia, as is partly conjectured.

Documented history

It is not yet possible to specify with any certainty when the great South Arabian Kingdoms appeared; estimates range (within the framework of the long chronology) from the 12th until the 8th century BCE.Kingdom of Saba (12th century BCE – 275 CE)

During Sabaean rule, trade and agriculture flourished generating much wealth and prosperity. The Sabaean kingdom was located in what is now the 'Asīr region in southwestern Saudi Arabia, and its capital, Ma'rib, is located near what is now Yemen's modern capital,Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

. According to Arab tradition, the eldest son of Noah

Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

, Shem

Shem (; ''Šēm''; ) is one of the sons of Noah in the Bible ( Genesis 5–11 and 1 Chronicles 1:4).

The children of Shem are Elam, Ashur, Arphaxad, Lud and Aram, in addition to unnamed daughters. Abraham, the patriarch of Jews, Christ ...

, founded the city of Sana’a, which is also called the city of Sam, or also called Azal city, which means the ancient city.

Sabaean hegemony (800 BCE – 400 BCE)

At the time of the earliest historical sources originating in South Arabia the territory was under the rule of the Kingdom of Saba', the centres of which were situated to the east of present-day Sana'a in Ṣirwāḥ and Ma'rib. The political map of South Arabia at that time consisted of several larger kingdoms, or rather tribal territories: Awsān, Qatabān and the Ḥaḑramawt; and on the other hand an uncertain number of smaller states, such as the city states of Ḥaram and Nashaq in al-Jawf. Shortly after, Yitha'amar Watar I had united Qatabān and some areas in al-Jawf with Saba', the Kingdom reached the peak of its power under Karib'il Watar I, who probably reigned some time around the first half of the 7th century BCE, and ruled all the region from Najrān in the south of modern South Arabia right up to Bāb al-Mandab, on the Red Sea. The formation of the Minaean Kingdom in the river oasis of al-Jawf, north-west of Saba' in the 6th century BCE, actually posed a danger for Sabaean hegemony, but Yitha'amar Bayyin II, who had completed the great reservoir dam of Ma'rib, succeeded in reconquering the northern part of South Arabia. Between the 8th and 4th centuries the state of Da'amot emerged, under Sabaean influence in Ethiopia, which survived until the beginning of the Christian era at the latest. The exact chronology of Da'amot and to what extent it was politically independent of Saba' remains in any case uncertain. The success of the Kingdom was based on the cultivation and trade of spices and aromatics includingfrankincense

Frankincense, also known as olibanum (), is an Aroma compound, aromatic resin used in incense and perfumes, obtained from trees of the genus ''Boswellia'' in the family (biology), family Burseraceae. The word is from Old French ('high-quality in ...

and myrrh

Myrrh (; from an unidentified ancient Semitic language, see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a few small, thorny tree species of the '' Commiphora'' genus, belonging to the Burseraceae family. Myrrh resin has been used ...

. These were exported to the Mediterranean, India, and Abyssinia where they were greatly prized by many cultures, using camels on routes through Arabia, and to India by sea. Evidence of Sabaean influence is found in northern Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

, where the South Arabian alphabet

The Ancient South Arabian script (Old South Arabian: ; modern ) branched from the Proto-Sinaitic script in about the late 2nd millennium BCE, and remained in use through the late sixth century CE. It is an abjad, a writing system where only con ...

, religion and pantheon, and the South Arabian style of art and architecture were introduced. The Sabaeans created a sense of identity through their religion. They worshipped El-Maqah and believed that they were his children. For centuries, the Sabaeans controlled outbound trade across the Bab-el-Mandeb, a strait separating the Arabian Peninsula from the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

and the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

from the Indian Ocean.

Agriculture in Yemen thrived during this time due to an advanced irrigation system which consisted of large water tunnels in mountains, and dams. The most impressive of these earthworks, known as the Ma'rib Dam was built c. 700 BCE, provided irrigation for about 25,000 acres (101 km²) of land and stood for over a millennium, finally collapsing in 570 CE after centuries of neglect. The final destruction of the dam is noted in the Qur'an and the consequent failure of the irrigation system provoked the migration of up to 50,000 people.

The Sabaean kingdom, with its capital at Ma'rib where the remains of a large temple can still be seen, thrived for almost 14 centuries. This kingdom was the Sheba

Sheba, or Saba, was an ancient South Arabian kingdoms in pre-Islamic Arabia, South Arabian kingdom that existed in Yemen (region), Yemen from to . Its inhabitants were the Sabaeans, who, as a people, were indissociable from the kingdom itself f ...

described in the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

.

Kingdom of Ḥaḑramawt (8th century BCE – 300 CE)

The first known inscriptions of Ḥaḑramawt are known from the 8th century BCE. It was first referenced by an outside civilization in an Old Sabaic inscription of Karab'il Watar from the early 7th century BCE, in which the King of Ḥaḑramawtt, Yada'il, is mentioned as being one of his allies. When the Minaeans took control of the caravan routes in the 4th century BCE, however, Ḥaḑramawt became one of its confederates, probably because of commercial interests. It later became independent and was invaded by the growing kingdom of Ḥimyar toward the end of the 1st century BCE, but it was able to repel the attack. Ḥaḑramawt annexed Qatabān in the second half of the 2nd century CE, reaching its greatest size. During this period, Ḥaḑramawt was continuously at war with Himyar and Saba', and the Sabaean king Sha'irum Awtar was even able to take its capital, Shabwah, in 225. During this period the

The first known inscriptions of Ḥaḑramawt are known from the 8th century BCE. It was first referenced by an outside civilization in an Old Sabaic inscription of Karab'il Watar from the early 7th century BCE, in which the King of Ḥaḑramawtt, Yada'il, is mentioned as being one of his allies. When the Minaeans took control of the caravan routes in the 4th century BCE, however, Ḥaḑramawt became one of its confederates, probably because of commercial interests. It later became independent and was invaded by the growing kingdom of Ḥimyar toward the end of the 1st century BCE, but it was able to repel the attack. Ḥaḑramawt annexed Qatabān in the second half of the 2nd century CE, reaching its greatest size. During this period, Ḥaḑramawt was continuously at war with Himyar and Saba', and the Sabaean king Sha'irum Awtar was even able to take its capital, Shabwah, in 225. During this period the Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum, or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom in East Africa and South Arabia from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, based in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, and spanning present-day Djibouti and Sudan. Emerging ...

began to interfere in South Arabian affairs. King GDRT of Aksum acted by dispatching troops under his son, BYGT, sending them from the western coast to occupy Thifar, the Ḥimyarite capital, as well as from the southern coast against Ḥaḑramawt as Sabaean allies. The kingdom of Ḥaḑramawt was eventually conquered by the Ḥimyarite king Shammar Yuhar'ish around 300 CE, unifying all of the south Arabic kingdoms.

Kingdom of Awsan (800 BCE – 500 BCE)

The ancient Kingdom of Awsān in South Arabia with a capital at Ḥajar Yaḥirr in Wādī Markhah, to the south of the Wādī Bayḥān, is now marked by a tell or artificial mound, which is locally named Ḥajar Asfal in Shabwah. Once it was one of the most important small kingdoms of South Arabia. The city seems to have been destroyed in the 7th century BCE by the king andmukarrib

Mukarrib (Old South Arabian: , romanized: ) is a title used by rulers in ancient South Arabia. It is attested as soon as continuous epigraphic evidence is available and it was used by the kingdoms of Saba, Hadhramaut, Qataban, and Awsan. The tit ...

of Saba Karib'il Watar, according to a Sabaean text that reports the victory in terms that attest to its significance for the Sabaeans.

Between 700 and 680 BC, the Kingdom of Awsan dominated Aden and its surroundings and challenged the Sabaean supremacy in South Arabia

South Arabia (), or Greater Yemen, is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it has also historically included Najran, Jazan, ...

. Sabaean Mukarrib Karib'il Watar I conquered Awsan, and expanded Sabaean rule and territory to include much of South Arabia. Lack of water in the Arabian Peninsula prevented the Sabaeans from unifying the entire peninsula. Instead, they established various colonies to control trade routes.

Kingdom of Qatabān (4th century BCE – 200 CE)

Qatabān was one of the ancient Yemeni kingdoms which thrived in the Bayḥān valley. Like the other Southern Arabian kingdoms it gained great wealth from the trade of frankincense and myrrh incense which were burned at altars. The capital of Qatabān was named Timna and was located on the trade route which passed through the other kingdoms of Ḥaḑramawt, Saba' and Ma'īn. The chief deity of the Qatabānians was 'Amm, or "Uncle" and the people called themselves the "children of 'Amm".Kingdom of Ma'in (8th century BCE – 100 BCE)

During Minaean rule, the capital was at Qarnāwu (now known asMa'in

Ma'in (; ) was an ancient South Arabian kingdom in modern-day Yemen. It was located along the strip of desert called Ramlat al-Sab'atayn, Ṣayhad by medieval Arab geographers, which is now known as Ramlat al-Sab'atayn. Wadd was the national ...

). Their other important city was Yathill (Sabaean yṯl :now known as Barāqish). Other parts of modern Yemen include Qatabā and the coastal string of watering stations known as the Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah and Mahrah, Dhofar in southwestern Oman, and Sharurah in the Najran Province of Saudi A ...

. Though Saba' dominated in the earlier period of South Arabian history, Minaic inscriptions are of the same time period as the first Sabaean inscriptions. They pre-date the appearance of the Minaeans themselves, and, hence, are called now more appropriately as "Madhābic", after the name of the Wadi they are found in, rather than "Minaic". The Minaean Kingdom was centered in northwestern Yemen, with most of its cities lying along the Wādī Madhhāb. Minaic inscriptions have been found far afield of the Kingdom of Ma'in, as far away as al-Ūlā in northwestern Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

and even on the island of Delos

Delos (; ; ''Dêlos'', ''Dâlos''), is a small Greek island near Mykonos, close to the centre of the Cyclades archipelago. Though only in area, it is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. ...

and in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. It was the first of the South Arabian kingdoms to end, and the Minaean language

The Minaean language (also Minaic, Madhabaic or Madhābic) was an Old South Arabian or Ṣayhadic language spoken in Yemen in the times of the Old South Arabian civilisation. The main area of its use may be located in the al-Jawf region of Nort ...

died around 100 CE.

Kingdom of Ḥimyar (2nd century BCE – 525 CE)

The Ḥimyarites eventually united Southwestern Arabia, controlling the Red Sea as well as the coasts of the Gulf of Aden. From their capital city, the Ḥimyarite kings launched successful military campaigns, and had stretched its domain at times as far east to the Persian Gulf and as far north as the Arabian Desert.

During the 3rd century CE, the South Arabian kingdoms were in continuous conflict with one another. GDRT of Aksum began to interfere in South Arabian affairs, signing an alliance with Saba', and a Ḥimyarite text notes that Ḥaḑramawt and Qatabān were also all allied against the kingdom. As a result of this, the Kingdom of Aksum was able to capture the Ḥimyarite capital of Ẓifār in the first quarter of the 3rd century. However, the alliances did not last, and Sha'ir Awtar of Saba' unexpectedly turned on Ḥadramawt, allying again with Aksum and taking its capital in 225. Ḥimyar then allied with Saba' and invaded the newly taken Aksumite territories, retaking Ẓifār, which had been under the control of GDRT's son BYGT, and pushing Aksum back into the Tihāmah.

They established their capital at Thifar (now just a small village in the Ibb region) and gradually absorbed the Sabaean kingdom. They traded from the port of Mawza'a on the Red Sea. Dhū Nuwās, a Ḥimyarite king, changed the state religion to

The Ḥimyarites eventually united Southwestern Arabia, controlling the Red Sea as well as the coasts of the Gulf of Aden. From their capital city, the Ḥimyarite kings launched successful military campaigns, and had stretched its domain at times as far east to the Persian Gulf and as far north as the Arabian Desert.

During the 3rd century CE, the South Arabian kingdoms were in continuous conflict with one another. GDRT of Aksum began to interfere in South Arabian affairs, signing an alliance with Saba', and a Ḥimyarite text notes that Ḥaḑramawt and Qatabān were also all allied against the kingdom. As a result of this, the Kingdom of Aksum was able to capture the Ḥimyarite capital of Ẓifār in the first quarter of the 3rd century. However, the alliances did not last, and Sha'ir Awtar of Saba' unexpectedly turned on Ḥadramawt, allying again with Aksum and taking its capital in 225. Ḥimyar then allied with Saba' and invaded the newly taken Aksumite territories, retaking Ẓifār, which had been under the control of GDRT's son BYGT, and pushing Aksum back into the Tihāmah.

They established their capital at Thifar (now just a small village in the Ibb region) and gradually absorbed the Sabaean kingdom. They traded from the port of Mawza'a on the Red Sea. Dhū Nuwās, a Ḥimyarite king, changed the state religion to Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

in the beginning of the 6th century and began to massacre the Christians. Outraged, Kaleb, the Christian King of Aksum with the encouragement of the Byzantine Emperor Justin I

Justin I (; ; 450 – 1 August 527), also called Justin the Thracian (; ), was Roman emperor from 518 to 527. Born to a peasant family, he rose through the ranks of the army to become commander of the imperial guard and when Emperor Anastasi ...

invaded and annexed Yemen. About fifty years later, Yemen fell to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

.

Kingdom of Aksum (520 – 570 CE)

Around 517/8, aJewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

king called Yūsuf Asar Yathar (also known as Dhū Nuwās) usurped the kingship of Ḥimyar from Ma'dikarib Ya'fur. Zacharias Rhetor

Zacharias of Mytilene (Ζαχαρίας ό Μιτυληναίος; c. 465, Gaza City, Gaza – after 536), also known as Zacharias Scholasticus or Zacharias Rhetor, was a bishop and ecclesiastical historian.

Life

The life of Zacharias of Mytile ...

of Mytilene

Mytilene (; ) is the capital city, capital of the Greece, Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of the Aegean. It was fo ...

(fl. late 6th century) says that Yūsuf became king because the previous king had died in winter, when the Aksumites could not cross the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

and appoint another king. The truth behind such a claim is put into doubt due to Ma'dikarib Ya'fur having a long title. Upon gaining power, Yusuf attacked the Aksumite garrison in Zafar, the Himyarite capital, killing many and destroying the church there. The Christian King Kaleb of Axum learned of Dhu Nuwas's persecutions of Christians and Aksumites, and, according to Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea (; ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; ; – 565) was a prominent Late antiquity, late antique Byzantine Greeks, Greek scholar and historian from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman general Belisarius in Justinian I, Empe ...

, was further encouraged by his ally and fellow Christian Justin I

Justin I (; ; 450 – 1 August 527), also called Justin the Thracian (; ), was Roman emperor from 518 to 527. Born to a peasant family, he rose through the ranks of the army to become commander of the imperial guard and when Emperor Anastasi ...

of Byzantium, who requested Aksum's help to cut off silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

supplies as part of his economic war against the Persians

Persians ( ), or the Persian people (), are an Iranian ethnic group from West Asia that came from an earlier group called the Proto-Iranians, which likely split from the Indo-Iranians in 1800 BCE from either Afghanistan or Central Asia. They ...

.

Yusuf marched toward the port city of Mocha, killing 14,000 and capturing 11,000. Then he settled a camp in Bab-el-Mandeb to prevent aid flowing from Aksum. At the same time, he sent an army under the command of another Jewish warlord, Sharahil Yaqbul, to Najran

Najran ( '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is the capital of Najran Province. Today, the city of Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As of the 2022 census, the city population was 381,431, wi ...

. Sharahil had reinforcements from the Bedouins of the Kinda and Madh'hij tribes, eventually wiping out the Christian community in Najran by means of execution and forced conversion

Forced conversion is the adoption of a religion or irreligion under duress. Someone who has been forced to convert to a different religion or irreligion may continue, covertly, to adhere to the beliefs and practices which were originally held, w ...

to Judaism. Blady speculates that he was likely motivated by stories about Byzantine violence against Byzantine Jewish communities in his decision to begin his campaign of state violence against Christians existing within his territory.

Christian sources portray Dhu Nuwas as a Jewish zealot, while Islamic traditions say that he marched around 20,000 Christians into trenches filled with flaming oil, burning them alive. Himyarite inscriptions attributed to Dhu Nuwas show great pride in killing 27,000, enslaving 20,500 Christians in Ẓafār and Najran

Najran ( '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is the capital of Najran Province. Today, the city of Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As of the 2022 census, the city population was 381,431, wi ...

and killing 570,000 beasts of burden belonging to them as a matter of imperial policy. It is reported that Byzantium Emperor Justin I

Justin I (; ; 450 – 1 August 527), also called Justin the Thracian (; ), was Roman emperor from 518 to 527. Born to a peasant family, he rose through the ranks of the army to become commander of the imperial guard and when Emperor Anastasi ...

sent a letter to the Aksumite King Kaleb, pressuring him to "...attack the abominable Hebrew." A military alliance of Byzantine, Aksumite, and Arab Christians successfully defeated Dhu Nuwas around 525–527 and a client Christian king was installed on the Himyarite throne.;

Esimiphaios was a local Christian lord, mentioned in an inscription celebrating the burning of an ancient Sabaean palace in Marib to build a church on its ruins. Three churches were built in Najran. Many tribes did not recognize Esimiphaios's authority. Esimiphaios was displaced in 531 by a warrior named Abraha, who refused to leave Yemen and declared himself an independent king of Himyar.

Kaleb sent a fleet across the Red Sea and was able to defeat Dhū Nuwās, who was killed in battle according to an inscription from Ḥusn al-Ghurāb, while later Arab tradition has him riding his horse into the sea. Kaleb installed a native Ḥimyarite viceroy, Samu Yafa', who ruled from 525–27 until 531, when he was deposed by the Aksumite general (or soldier and former slave) Abrahah with the support of disgruntled Axum

Axum, also spelled Aksum (), is a town in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia with a population of 66,900 residents (as of 2015). It is the site of the historic capital of the Aksumite Empire.

Axum is located in the Central Zone of the Tigray Re ...

n soldiers. A contemporary inscription refers to Sumyafa' Ashwa' as "viceroy for the kings of Aksum. According to the later Arabic sources, Kaleb retaliated by sending a force of 3,000 men under a relative, but the troops defected and killed their leader, and a second attempt at reigning in the rebellious Abrahah also failed. Later Ethiopian sources state that Kaleb abdicated to live out his years in a monastery and sent his crown to be hung in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, also known as the Church of the Resurrection, is a fourth-century church in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem, Old City of Jerusalem. The church is the seat of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchat ...

in Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

. While uncertain, it seems to be supported by the die-links between his coins and those of his successor, Alla Amidas. An inscription of Sumyafa' Ashwa' also mentions two kings (''nagaśt'') of Aksum, indicating that the two may have co-ruled for a while before Kaleb abdicated in favor of Alla Amidas.

Procopius notes that Abrahah later submitted to Kaleb's successor, as supported by the former's inscription in 543 stating Aksum before the territories directly under his control. During his reign, Abrahah repaired the Ma'rib Dam in 543, and received embassies from Persia and Byzantium, including a request to free some bishops who had been imprisoned at Nisibis

Nusaybin () is a municipality and Districts of Turkey, district of Mardin Province, Turkey. Its area is 1,079 km2, and its population is 115,586 (2022). The city is populated by Kurds of different tribal affiliation.

Nusaybin is separated ...

(according to John of Ephesus's "Life of Simeon"). Abraha ruled until at least 547, sometime after which he was succeeded by his son, Aksum. Aksum (called "Yaksum" in Arabic sources) was perplexingly referred to as "of Ma'afir" (''ḏū maʻāfir''), the southwestern coast of Yemen, in Abrahah's Ma'rib dam inscription, and was succeeded by his brother, Masrūq. Aksumite control in Yemen ended in 570 with the invasion of the elder Sassanid general Vahriz who, according to later legends, famously killed Masrūq with his well-aimed arrow.

Later Arabic sources also say that Abrahah constructed a great Church called "al-Qulays" at Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

in order to divert pilgrimage from the Ka'bah

The Kaaba (), also spelled Kaba, Kabah or Kabah, sometimes referred to as al-Kaba al-Musharrafa (), is a stone building at the center of Islam's most important mosque and Holiest sites in Islam, holiest site, the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, Sa ...

and have him die in the Year of the Elephant

The ʿām al-fīl (, Year of the Elephant) is the name in Islamic history for the year approximately equating to 570–571 CE. According to Islamic resources, it was in this year that prophet Mohammad was born.Hajjah Adil, Amina, "''Prophet ...

(570) after returning from a failed attack on Mecca (though he is thought to have died before this time). The exact chronology of the early wars are uncertain, as a 525 inscription mentions the death of a King of Ḥimyar, which could refer either to the Ḥimyarite viceroy of Aksum, Sumyafa' Ashwa', or to Yusuf Asar Yathar. The later Arabic histories also mention a conflict between Abrahah and another Aksumite general named Aryat occurring in 525 as leading to the rebellion.

Sassanid period (570–630 CE)

EmperorKhosrow I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; ), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ("the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 531 to 579. He was the son and successor of Kavad I ().

Inheriting a rei ...

sent troops under the command of Wahrez, who helped the semi-legendary Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan to drive the Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum, or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom in East Africa and South Arabia from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, based in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, and spanning present-day Djibouti and Sudan. Emerging ...

out of Yemen. South Arabia became a Persian dominion under a Yemenite vassal and thus came within the sphere of influence of the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranian peoples, Iranians"), was an List of monarchs of Iran, Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, th ...

. Later another army was sent to Yemen, and in 597/8 Southern Arabia became a province of the Sassanid Empire under a Persian satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

. It was a Persian province by name but after the Persians assassinated Dhi Yazan, Yemen divided into a number of autonomous kingdoms.

This development was a consequence of the expansionary policy pursued by the Sassanian king Khosrow II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; and ''Khosrau''), commonly known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian King of Kings (Shahanshah) of Iran, ruling from 590 ...

(590–628), whose aim was to secure Persian border areas such as Yemen against Roman and Byzantine incursions. Following the death of Khosrau II in 628, then the Persian governor in Southern Arabia, Badhan, converted to Islam and Yemen followed the new religion.

See also

*Pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia is the Arabian Peninsula and its northern extension in the Syrian Desert before the rise of Islam. This is consistent with how contemporaries used the term ''Arabia'' or where they said Arabs lived, which was not limited to the ...

*Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was home to many cradles of civilization, spanning Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran (or Persia), Anatolia and the Armenian highlands, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. As such, the fields of ancient Near East studies and Nea ...

* Ancient South Arabian art

* Islamic history of Yemen

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * Link is to text lacking page numbers. * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * *External links

* * * *A Dam at Marib

Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions

Università degli studi di Pisa. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ancient History Of Yemen