Anarchism And Violence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anarchism and violence have been linked together by events in anarchist history such as violent revolution,

Some anarchists, such as

Some anarchists, such as

Anarcho-pacifism (also pacifist anarchism or anarchist pacifism) is a form of anarchism which completely rejects the use of violence in any form for any purpose. Important proponents include

Anarcho-pacifism (also pacifist anarchism or anarchist pacifism) is a form of anarchism which completely rejects the use of violence in any form for any purpose. Important proponents include

* August 8, 1897 – Michele Angiolillo shoots dead

* August 8, 1897 – Michele Angiolillo shoots dead  * September 10, 1898 – Luigi Lucheni stabs to death Empress Elisabeth, the consort of Emperor

* September 10, 1898 – Luigi Lucheni stabs to death Empress Elisabeth, the consort of Emperor

"Bomb Menaces Life of Sacco Case Judge", September 27, 1932

accessed December 20, 2009Cannistraro, Philip V., and Meyer, Gerald, eds., ''The Lost World of Italian-American Radicalism: Politics, Labor, and Culture'', Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, (2003) p. 168 Judge Thayer had presided over the trials of ''Galleanists''

The Story of Anarchist Violence

" ''The Anarchist Library''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Anarchism And Violence History of anarchism Insurrectionary anarchism Issues in anarchism Violence

terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

, and assassination attempts. Leading late 19th century anarchists espoused propaganda by deed, or ''attentáts'', and was associated with a number of incidents of political violence

Political violence is violence which is perpetrated in order to achieve political goals. It can include violence which is used by a State (polity), state against other states (war), violence which is used by a state against civilians and non-st ...

. Anarchist thought, however, is quite diverse on the question of violence. Where some anarchists have opposed coercive

Coercion involves compelling a party to act in an involuntary manner through the use of threats, including threats to use force against that party. It involves a set of forceful actions which violate the free will of an individual in order to in ...

means on the basis of coherence, others have supported acts of violent revolution as a path toward anarchy. Anarcho-pacifism

Anarcho-pacifism, also referred to as anarchist pacifism and pacifist anarchism, is an anarchist school of thought that advocates for the use of peaceful, non-violent forms of resistance in the struggle for social change. Anarcho-pacifism reject ...

is a school of thought within anarchism which rejects all violence.

Many anarchists regard the state to be at the definitional center of structural violence

Structural violence is a form of violence wherein some social structure or social institution may harm people by preventing them from meeting their basic needs or rights.

The term was coined by Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung, who intr ...

: directly or indirectly preventing people from meeting their basic needs, calling for violence as self-defense.

Perhaps the first anarchist periodical was named '' The Peaceful Revolutionist''.

Propaganda by deed

Propaganda by deed (or propaganda of the deed, from the French ) is specific politicaldirect action

Direct action is a term for economic and political behavior in which participants use agency—for example economic or physical power—to achieve their goals. The aim of direct action is to either obstruct a certain practice (such as a governm ...

meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution. It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by proponents of insurrectionary anarchism

Insurrectionary anarchism is a revolutionary theory and tendency within the anarchist movement that emphasizes insurrection as a revolutionary practice. It is critical of formal organizations such as labor unions and federations that are based on ...

in the late 19th and early 20th century, including bombings and assassinations

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

aimed at the State, the ruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society.

In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the class who own the means of production in a given society and apply ...

, and Church arson

Church arson is burning or attempting to burn religious property, because empty churches are soft targets, racial hatred, pyromania, prejudice against certain religious beliefs, greed, or as part of communal violence or dissent or anti-religious ...

s targeting religious groups, even though propaganda of the deed also had non-violent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

applications. These acts of terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

were intended to ignite a "spirit of revolt" by demonstrating the state, the middle and upper classes, and religious organizations were not omnipotent and also to provoke the State to become escalatingly repressive in its response. The 1881 London Social Revolutionary Congress

The International Social Revolutionary Congress was an anarchist meeting in London between 14 and 20 July 1881, with the aim of founding a new International organization for anti-authoritiarian socialism (i.e., anarchists).

Preparations

Pla ...

gave the tactic its approval.

The Italian revolutionary Carlo Pisacane wrote in his "Political Testament" (1857) that "ideas spring from deeds and not the other way around" and Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin. Sometimes anglicized to Michael Bakunin. ( ; – 1 July 1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, s ...

stated in 1870 that "we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda." By the 1880s, the slogan "propaganda by deed" had begun to be used both within and outside of the anarchist movement to refer to individual bombings, regicide

Regicide is the purposeful killing of a monarch or sovereign of a polity and is often associated with the usurpation of power. A regicide can also be the person responsible for the killing. The word comes from the Latin roots of ''regis'' ...

s and tyrannicide

Tyrannicide is the killing or assassination of a tyrant or unjust ruler, purportedly for the common good, and usually by one of the tyrant's subjects. Tyrannicide was legally permitted and encouraged in Classical Athens. Often, the term "tyrant ...

s, and was formally adopted as a strategy by the anarchist 1881 London Social Revolutionary Congress

The International Social Revolutionary Congress was an anarchist meeting in London between 14 and 20 July 1881, with the aim of founding a new International organization for anti-authoritiarian socialism (i.e., anarchists).

Preparations

Pla ...

.

While revolutionary bombings and assassinations appeared as an indiscriminate call to violence to outsiders, anarchists saw "the idea of the propaganda by deed, or the ''attentat'' (attack), s havinga very specific logic". In a capitalist world founded on force and constant threat of violence (laws, church, paychecks), "to do nothing, to stand idly by while millions suffered, was itself to commit an act of violence". This did not seek to justify violence but find what violence would effectively undo malignant state forces. Propaganda by deed included stealing (in particular bank robberies

Bank robbery is the criminal act of stealing from a bank, specifically while bank employees and customers are subjected to force, violence, or a threat of violence. This refers to robbery of a bank Branch (banking), branch or Bank teller, tel ...

– named "expropriations" or "revolutionary expropriations" to finance the organization), rioting and general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...

s which aimed at creating the conditions of an insurrection or even a revolution. These acts were justified as the necessary counterpart to state repression. As early as 1911, Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

condemned individual acts of violence by anarchists as useful for little more than providing an excuse for state repression. "The anarchist prophets of the 'propaganda by the deed' can argue all they want about the elevating and stimulating influence of terrorist acts on the masses," he wrote in 1911, "Theoretical considerations and political experience prove otherwise." Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

largely agreed, viewing individual anarchist acts of terrorism as an ineffective substitute for coordinated action by disciplined cadres of the masses. Both Lenin and Trotsky acknowledged the necessity of violent rebellion and assassination to serve as a catalyst for revolution, but they distinguished between the ''ad hoc'' bombings and assassinations carried out by proponents of the propaganda by deed, and organized violence coordinated by a professional revolutionary vanguard utilized for that specific end.

Some anarchists, such as

Some anarchists, such as Johann Most

Johann Joseph "Hans" Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American Social Democratic and then anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "propaganda of the deed" in the Un ...

, advocated publicizing violent acts of retaliation against counter-revolutionaries to "preach ... action as propaganda". It was not advocacy for mass murder, but a call for targeted killings

Targeted killing is a form of assassination carried out by governments outside a judicial procedure or a battlefield.

Since the late 20th century, the legal status of targeted killing has become a subject of contention within and between variou ...

of the representatives of capitalism and government at a time when such action might garner sympathy from the population, such as during periods of government repression or labor conflicts, although Most himself once claimed that "the existing system will be quickest and most radically overthrown by the annihilation of its exponents. Therefore, massacres of the enemies of the people must be set in motion." In 1885, he published ''The Science of Revolutionary Warfare'', a technical manual for acquiring and detonating explosives based on the knowledge he acquired by working at an explosives factory in New Jersey. Most was an early influence on American anarchists Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

and Alexander Berkman. Berkman attempted propaganda by deed when he tried in 1892 to kill industrialist Henry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick (December 19, 1849 – December 2, 1919) was an American industrialist, financier, and art patron. He founded the H. C. Frick & Company coke manufacturing company, was chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company and played a major ...

following the deaths by shooting of several striking workers.

As early as 1887, a few important figures in the anarchist movement had begun to distance themselves from individual acts of violence. Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist and geographer known as a proponent of anarchist communism.

Born into an aristocratic land-owning family, Kropotkin attended the Page Corps and later s ...

thus wrote that year in ''Le Révolté'' that "a structure based on centuries of history cannot be destroyed with a few kilos of dynamite". A variety of anarchists advocated the abandonment of these sorts of tactics in favor of collective revolutionary action, for example through the trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

movement. The anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is an anarchist organisational model that centres trade unions as a vehicle for class conflict. Drawing from the theory of libertarian socialism and the practice of syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalism sees trade unions as both ...

, Fernand Pelloutier, argued in 1895 for renewed anarchist involvement in the labor movement on the basis that anarchism could do very well without "the individual dynamiter." State repression (including the infamous 1894 French '' lois scélérates'') of the anarchist and labor movement

The labour movement is the collective organisation of working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It can be considere ...

s following the few successful bombings and assassinations may have contributed to the abandonment of these kinds of tactics, although reciprocally state repression, in the first place, may have played a role in these isolated acts. The dismemberment of the French socialist movement

The history of socialism has its origins in the Age of Enlightenment and the 1789 French Revolution, along with the changes that brought, although it has precedents in earlier movements and ideas. ''The Communist Manifesto'' was written by Karl ...

, into many groups and, following the suppression of the 1871 Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

, the execution and exile of many ''communards

The Communards () were members and supporters of the short-lived 1871 Paris Commune formed in the wake of the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. After the suppression of the Commune by the French Army in May 1871, 43,000 Communards we ...

'' to penal colonies

A penal colony or exile colony is a Human settlement, settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colony, colonial territory. Although the te ...

, favored individualist political expression and acts.

The anarchist Luigi Galleani

Luigi Galleani (; 12 August 1861 – 4 November 1931) was an Italian insurrectionary anarchism, insurrectionary anarchist and Communism, communist best known for his advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", a strategy of political assassinations ...

, perhaps the most vocal proponent of propaganda by deed from the turn of the century through the end of the First World War, took undisguised pride in describing himself as a subversive, a revolutionary propagandist and advocate of the violent overthrow of established government and institutions through the use of 'direct action', i.e., bombings and assassinations.Galleani, Luigi, ''La Fine Dell'Anarchismo?'', ed. Curata da Vecchi Lettori di Cronaca Sovversiva, University of Michigan (1925), pp. 61–62: Galleani's writings are clear on this point: he had undisguised contempt for those who refused to both advocate and ''directly participate'' in the violent overthrow of capitalism.Galleani, Luigi, ''Faccia a Faccia col Nemico'', Boston, MA: Gruppo Autonomo, (1914) Galleani heartily embraced physical violence and terrorism, not only against symbols of the government and the capitalist system, such as courthouses and factories, but also through direct assassination of 'enemies of the people': capitalists, industrialists, politicians, judges, and policemen.Avrich, Paul, ''Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background'', Princeton University Press (1991), pp. 51, 98–99 He had a particular interest in the use of bombs, going so far as to include a formula for the explosive nitroglycerine

Nitroglycerin (NG) (alternative spelling nitroglycerine), also known as trinitroglycerol (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless or pale yellow, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by ...

in one of his pamphlets advertised through his monthly magazine, ''Cronaca Sovversiva

''Cronaca Sovversiva'' (Subversive Chronicle) was an Italian-language, anarchism in the United States, United States–based anarchist newspaper associated with Luigi Galleani from 1903 to 1920. It is one of the country's most significant Anarc ...

''. By all accounts, Galleani was an extremely effective speaker and advocate of his policy of violent action, attracting a number of devoted Italian-American anarchist followers who called themselves Galleanists. Carlo Buda, the brother of Galleanist bombmaker Mario Buda, said of him, "You heard Galleani speak, and you were ready to shoot the first policeman you saw".

Anarcho-pacifism

Anarcho-pacifism (also pacifist anarchism or anarchist pacifism) is a form of anarchism which completely rejects the use of violence in any form for any purpose. Important proponents include

Anarcho-pacifism (also pacifist anarchism or anarchist pacifism) is a form of anarchism which completely rejects the use of violence in any form for any purpose. Important proponents include Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

and Bart de Ligt

Bartholomeus de Ligt (17 July 1883 – 3 September 1938) was a Dutch anarcho-pacifist and antimilitarist. He is chiefly known for his support of conscientious objectors.

Life and work

Born on 17 July 1883 in Schalkwijk, Utrecht, his father wa ...

. Mohandas Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British ...

is an important influence.

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (born David Henry Thoreau; July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon sim ...

, though not a pacifist himself, influenced both Leo Tolstoy and Mohandas Gandhi's advocacy of Nonviolent resistance

Nonviolent resistance, or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, construct ...

through his work ''Civil Disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active and professed refusal of a citizenship, citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders, or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be cal ...

''.

At some point anarcho-pacifism had as its main proponent Christian anarchism

Christian anarchism is a Christian movement in political theology that claims anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the Gospels. It is grounded in the belief that there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately answ ...

. The first large-scale anarcho-pacifist movement was the Tolstoyan peasant movement in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. They were a predominantly peasant movement that set up hundreds of voluntary anarchist pacifist communes based on their interpretation of Christianity as requiring absolute pacifism and the rejection of all coercive authority.

"Dutch anarchist-pacifist Bart de Ligt's 1936 treatise ''The Conquest of Violence'' (with its none too subtle allusion to Kropotkin's ''The Conquest of Bread'') was also of signal importance." "Gandhi's ideas were popularized in the West in books such as Richard Gregg's ''The Power of Nonviolence'' (1935), and Bart de Ligt's ''The Conquest of Violence'' (1937).

Peter Gelderloos

Peter Gelderloos (born ) is an American anarchist activist and writer.

Biography

Gelderloos first became involved in political issues as a high school student, and described the Seattle WTO protests in November 1999 as helping influence his ...

criticizes the idea that nonviolence is the only way to fight for a better world. According to Gelderloos, pacifism as an ideology serves the interests of the state.

Anarchist theory

Anarchism encompasses a variety of views about violence. The Tolstoyan tradition of non-violent resistance is prevalent among some anarchists.Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula Kroeber Le Guin ( ; Kroeber; October 21, 1929 – January 22, 2018) was an American author. She is best known for her works of speculative fiction, including science fiction works set in her Hainish universe, and the ''Earthsea'' fantas ...

's novel ''The Dispossessed

''The Dispossessed'' (subtitled ''An Ambiguous Utopia'') is a 1974 anarchist utopian science fiction novel by American writer Ursula K. Le Guin, one of her seven Hainish Cycle novels. It is one of a small number of books to win all three Hugo, ...

'', a fictional novel about a society that practices "Odonianism", expressed this anarchism:

Emma Goldman included in her definition of Anarchism the observation that all governments rest on violence, and this is one of the many reasons they should be opposed. Goldman herself didn't oppose tactics like assassination in her early career, but changed her views after she went to Russia, where she witnessed the violence of the Russian state and the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

. From then on she condemned the use of terrorism, especially by the state, and advocated violence only as a means of self-defense.

Discourse on violent and non-violent means

Some anarchists see violent revolution as necessary in the abolition of capitalist society, while others advocate non-violent methods.Errico Malatesta

Errico Malatesta (4 December 1853 – 22 July 1932) was an Italian anarchist propagandist, theorist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expel ...

, an anarcho-communist, propounded that it is "necessary to destroy with violence, since one cannot do otherwise, the violence which denies he means of life and for developmentto the workers." As he put it in '' Umanità Nova'' (no. 125, September 6, 1921):

Anarchists with this view advocate violence insofar as they see it to be necessary in ridding the world of exploitation, and especially states.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, ; ; 1809 – 19 January 1865) was a French anarchist, socialist, philosopher, and economist who founded mutualist philosophy and is considered by many to be the "father of anarchism". He was the first person to ca ...

argued in favor of a non-violent revolution through a process of dual power in which libertarian socialist institutions would be established and form associations enabling the formation of an expanding network within the existing state-capitalist framework with the intention of eventually rendering both the state and the capitalist economy obsolete. The progression towards violence in anarchism stemmed, in part, from the massacres of some of the communes inspired by the ideas of Proudhon and others. Many anarcho-communists began to see a need for revolutionary violence to counteract the violence inherent in both capitalism and government.

Anarcho-pacifism

Anarcho-pacifism, also referred to as anarchist pacifism and pacifist anarchism, is an anarchist school of thought that advocates for the use of peaceful, non-violent forms of resistance in the struggle for social change. Anarcho-pacifism reject ...

is a tendency within the anarchist movement which rejects the use of violence in the struggle for social change. The main early influences were the thought of Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (born David Henry Thoreau; July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon sim ...

and Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

. It developed "mostly in Holland, Britain, and the United States, before and during the Second World War". Opposition to the use of violence has not prohibited anarcho-pacifists from accepting the principle of resistance or even revolutionary action provided it does not result in violence; it was in fact their approval of such forms of opposition to power that lead many anarcho-pacifists to endorse the anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is an anarchist organisational model that centres trade unions as a vehicle for class conflict. Drawing from the theory of libertarian socialism and the practice of syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalism sees trade unions as both ...

concept of the general strike as the great revolutionary weapon. Later anarcho-pacifists have also come to endorse the non-violent strategy of dual power.

Other anarchists have believed that violence is justified, especially in self-defense

Self-defense (self-defence primarily in Commonwealth English) is a countermeasure that involves defending the health and well-being of oneself from harm. The use of the right of self-defense as a legal justification for the use of Force (law), ...

, as a way to provoke social upheaval which could lead to a social revolution.

Peter Gelderloos

Peter Gelderloos (born ) is an American anarchist activist and writer.

Biography

Gelderloos first became involved in political issues as a high school student, and described the Seattle WTO protests in November 1999 as helping influence his ...

criticizes the idea that nonviolence is the only way to fight for a better world. According to Gelderloos, pacifism as an ideology serves the interests of the state and is hopelessly caught up psychologically with the control schema of patriarchy and white supremacy. The influential publishing collective CrimethInc. notes that "violence" and "nonviolence" are politicized terms that are used inconsistently in discourse, depending on whether or not a writer seeks to legitimize the actor in question. They argue that " 's not strategic or anarchiststo focus on delegitimizing each other's efforts rather than coordinating to act together where we overlap". For this reason, both CrimethInc. and Gelderloos advocate for diversity of tactics

Diversity of tactics is a phenomenon wherein a social movement makes periodic use of force for disruptive or defensive purposes, stepping beyond the limits of nonviolent resistance, but also stopping short of total militarization. It also refer ...

. Albert Meltzer criticised extreme pacifism as authoritarian, believing that "The cult of extreme nonviolence always implies an elite." However, he did believe that less extreme pacifism was compatible with anarchism.

Notable actions

* * July 23, 1892 – Alexander Berkman tries to kill American industrialistHenry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick (December 19, 1849 – December 2, 1919) was an American industrialist, financier, and art patron. He founded the H. C. Frick & Company coke manufacturing company, was chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company and played a major ...

in retaliation for the hiring of Pinkerton detectives to break up the Homestead Strike, resulting in the deaths of seven striking members of the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers. Although badly wounded, Frick survives, and Berkman is arrested and eventually sentenced to 22 years in prison.

* November 7, 1893 – The Spanish anarchist Santiago Salvador throws two Orsini bomb

The Orsini bomb was a terrorism, terrorist improvised explosive device built by and named after Felice Orsini and used as a Grenade, hand grenade on 14 January 1858 in Orsini affair, an unsuccessful attack on Napoleon III. The weapons were som ...

s into the orchestra pit

An orchestra pit is an area in a theatre (usually located in a lowered area in front of the stage) in which musicians perform. The orchestra plays mostly out of sight in the pit, rather than on the stage as for a concert, when providing music fo ...

of the Liceu Theater in Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

during the second act of the opera ''Guillaume Tell

William Tell (, ; ; ; ) is a legendary folk hero of Switzerland. He is known for Shooting an apple off one's child's head, shooting an apple off his son's head.

According to the legend, Tell was an expert mountain climber and marksman with a cro ...

'', killing some twenty people and injuring scores of others.

* December 9, 1893 – Auguste Vaillant throws a nail bomb

A nail bomb is an anti-personnel explosive device containing nails to increase its effectiveness at harming victims. The nails act as shrapnel, leading almost certainly to more injury in inhabited areas than the explosives alone would. A nail ...

in the French National Assembly

The National Assembly (, ) is the lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral French Parliament under the French Fifth Republic, Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (France), Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are known ...

, killing nobody and injuring one. He is then sentenced to death and executed by the guillotine

A guillotine ( ) is an apparatus designed for effectively carrying out executions by Decapitation, beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secur ...

on February 4, 1894, shouting "Death to bourgeois society and long live anarchy!" (''À mort la société bourgeoise et vive l'anarchie!''). During his trial, Vaillant declares that he had not intended to kill anybody, but only to injure several deputies in retaliation against the execution of Ravachol

François Claudius Ravachol (; born Koenigstein; 14 October 1859 – 11 July 1892) was a French illegalist anarchist mainly known for his terrorist activism, impact, the myths developed around his figure and his influence on the anarchist moveme ...

, who was executed for four bombings.

* February 12, 1894 – Émile Henry, intending to avenge Auguste Vaillant, sets off a bomb in ''Café Terminus'' (a café near the Gare Saint-Lazare

The Gare Saint-Lazare (; ), officially Paris Saint Lazare, is one of the seven large mainline List of Paris railway stations, railway station terminals in Paris, France. It was the first railway station built in Paris, opening in 1837. It mostly ...

train station in Paris), killing one and injuring twenty. During his trial, when asked why he wanted to harm so many innocent people, he declares, "There is no innocent bourgeois." This act is one of the rare exceptions to the rule that propaganda by deed targets only specific powerful individuals. Henry was convicted and executed by guillotine on May 21.

* February 15, 1894 – A chemical explosive carried by Martial Bourdin prematurely detonates outside the Royal Observatory, Greenwich

The Royal Observatory, Greenwich (ROG; known as the Old Royal Observatory from 1957 to 1998, when the working Royal Greenwich Observatory, RGO, temporarily moved south from Greenwich to Herstmonceux) is an observatory situated on a hill in Gre ...

in Greenwich Park

Greenwich Park is a former hunting park in Greenwich and one of the largest single green spaces in south-east London. One of the eight Royal Parks of London, and the first to be enclosed (in 1433), it covers , and is part of the Greenwich World H ...

, killing him.

* June 24, 1894 – Italian anarchist Sante Geronimo Caserio

Sante Geronimo Caserio (; 8 September 187316 August 1894) was an Italian baker, Anarchism, anarchist, and Propaganda of the deed, propagandist by the deed. He is primarily known for Assassination of Sadi Carnot, assassinating Sadi Carnot, the sit ...

, seeking revenge for Auguste Vaillant and Émile Henry, stabs Sadi Carnot, the President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is the supreme magistracy of the country, the po ...

, to death. Caserio is executed by guillotine on August 15.

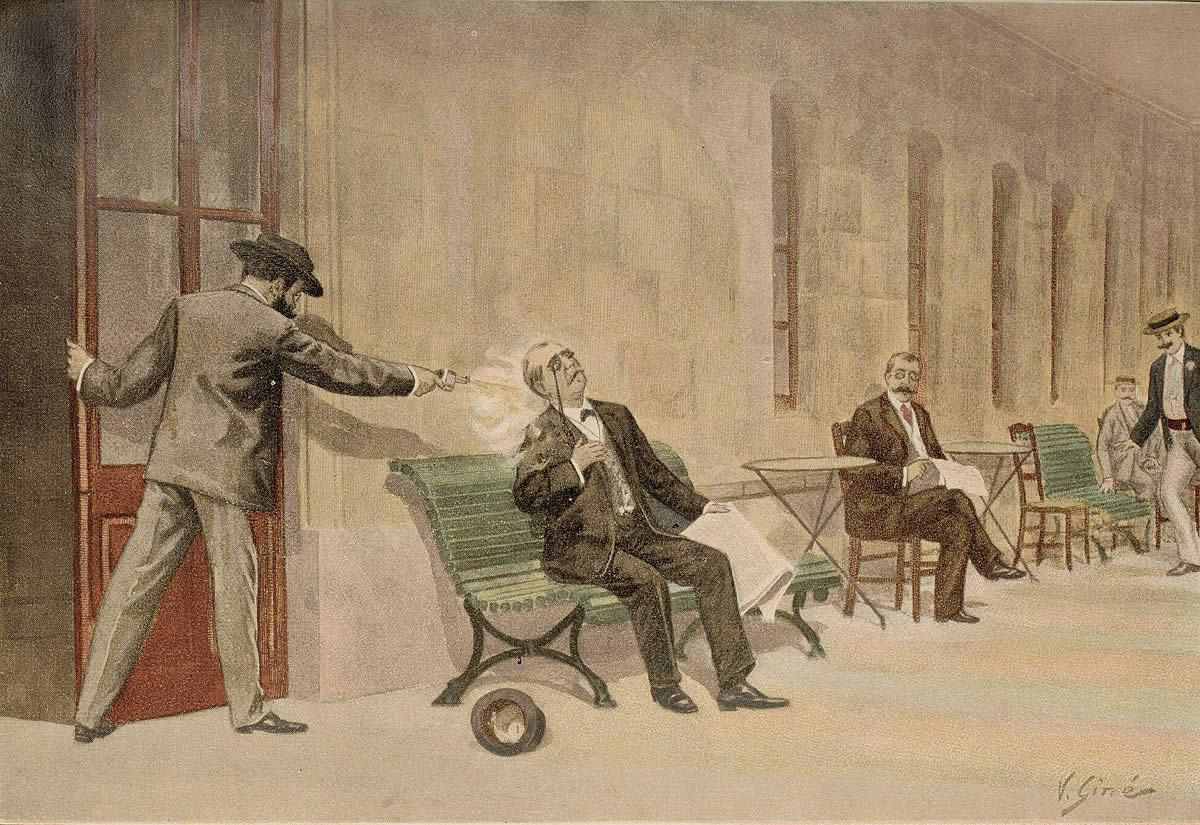

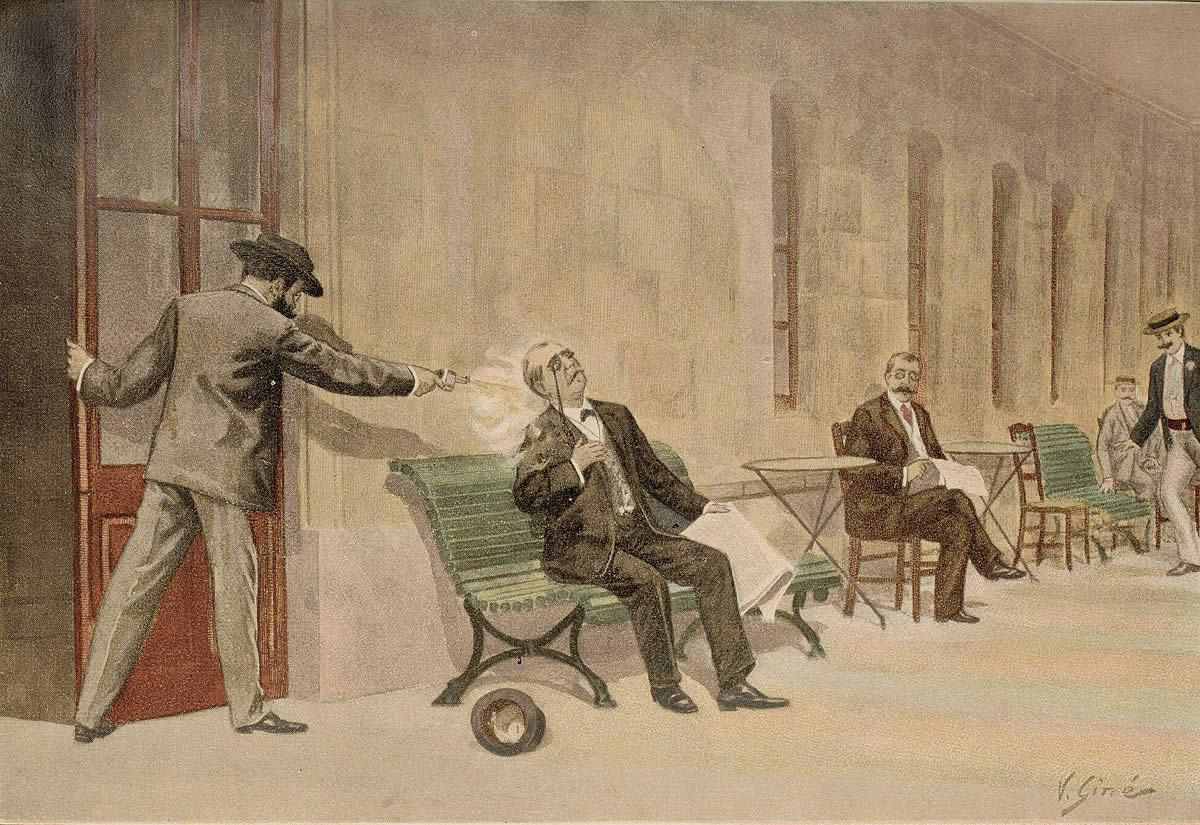

* August 8, 1897 – Michele Angiolillo shoots dead

* August 8, 1897 – Michele Angiolillo shoots dead Spanish Prime Minister

The prime minister of Spain, officially president of the Government (), is the head of government of Spain. The prime minister nominates the ministers and chairs the Council of Ministers. In this sense, the prime minister establishes the Gove ...

Antonio Cánovas del Castillo

Antonio Cánovas del Castillo (8 February 18288 August 1897) was a Spanish people, Spanish politician and historian known principally for serving six terms as Spanish Prime Minister, prime minister and his overarching role as "architect" of the ...

at a thermal bath resort, seeking vengeance for the imprisonment and torture of alleged revolutionaries in the Montjuïc trial. Angiolillo is executed by garotte on August 20.

* September 10, 1898 – Luigi Lucheni stabs to death Empress Elisabeth, the consort of Emperor

* September 10, 1898 – Luigi Lucheni stabs to death Empress Elisabeth, the consort of Emperor Franz Joseph I

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I ( ; ; 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the ruler of the Grand title of the emperor of Austria, other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 1848 until his death ...

of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, with a needle file in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, Switzerland. Lucheni is sentenced to life in prison and eventually commits suicide in his cell.

* July 29, 1900 – Gaetano Bresci shoots dead King Umberto of Italy, in revenge for the Bava Beccaris massacre in Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

. Due to the abolition of capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

in Italy, Bresci is sentenced to penal servitude for life on Santo Stefano Island, where he is found dead less than a year later.

* September 6, 1901 – Leon Czolgosz

Leon Frank Czolgosz ( ; ; May 5, 1873 – October 29, 1901) was an American wireworker and Anarchism, anarchist who assassination of William McKinley, assassinated President of the United States, United States president William McKinley on Septe ...

fatally shoots U.S. President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

at point-blank range at the Pan-American Exposition

The Pan-American Exposition was a world's fair held in Buffalo, New York, United States, from May 1 through November 2, 1901. The fair occupied of land on the western edge of what is now Delaware Park–Front Park System, Delaware Park, extending ...

in Buffalo, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

. McKinley dies on September 14, and Czolgosz is executed by electric chair

The electric chair is a specialized device used for capital punishment through electrocution. The condemned is strapped to a custom wooden chair and electrocuted via electrodes attached to the head and leg. Alfred P. Southwick, a Buffalo, New Yo ...

on October 29. Czolgosz's anarchist views have been debated.

* November 15, 1902 – Gennaro Rubino attempts to murder King Leopold II of Belgium

Leopold II (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909) was the second king of the Belgians from 1865 to 1909, and the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908.

Born in Brussels as the second but eldest-surviving son of King Leo ...

as he returns in a procession from a Requiem Mass

A Requiem (Latin: ''rest'') or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead () or Mass of the dead (), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the souls of the deceased, using a particular form of the Roman Missal. It is u ...

for his recently deceased wife, Queen Marie Henriette. All three of Rubino's shots miss the monarch's carriage, and he is quickly subdued by the crowd and taken into police custody. He is sentenced to life imprisonment and dies in prison in 1918.

* July 21, 1905 – Members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (, abbr. ARF (ՀՅԴ) or ARF-D), also known as Dashnaktsutyun (Armenians, Armenian: Դաշնակցություն, Literal translation, lit. "Federation"), is an Armenian nationalism, Armenian nationalist a ...

launch an attempt on the life of Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II

Abdulhamid II or Abdul Hamid II (; ; 21 September 184210 February 1918) was the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1876 to 1909, and the last sultan to exert effective control over the fracturing state. He oversaw a Decline and modernizati ...

, but the bomb missed its target, instead killing 26 people and wounded 58 others. One of the conspirators, the Armenian anarchist Christapor Mikaelian, was killed during the planning stages. The Belgian anarchist Edward Joris was also among those arrested and convicted for their part in the plot.

* May 31, 1906 – Catalan anarchist Mateu Morral tries to kill King Alfonso XIII of Spain

Alfonso XIII ( Spanish: ''Alfonso León Fernando María Jaime Isidro Pascual Antonio de Borbón y Habsburgo-Lorena''; French: ''Alphonse Léon Ferdinand Marie Jacques Isidore Pascal Antoine de Bourbon''; 17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also ...

and Queen Victoria Eugenie immediately after their wedding by throwing a bomb into the procession. The King and Queen are unhurt, but 24 bystanders and horses are killed and over 100 persons injured. Morral is apprehended two days later and commits suicide while being transferred to prison.

* February 1, 1908 – Manuel Buíça and Alfredo Costa shoot to death King Carlos I of Portugal

Dom (title), ''Dom'' Carlos I (; 28 September 1863 – 1 February 1908), known as "the Diplomat" (), "the Oceanographer" () among many other names, was List of Portuguese monarchs, King of Portugal from 1889 until his Lisbon Regicide, assassin ...

and his son, Crown Prince Luís Filipe, respectively, in the Lisbon Regicide

The Lisbon Regicide or Regicide of 1908 () was the assassination of Carlos I of Portugal, King Carlos I of Portugal and the Algarves and his heir-apparent, Luís Filipe, Prince Royal of Portugal, by assassins sympathetic to Republicanism, Republic ...

. Both Buíça and Costa, who are sympathetic to a republican movement in Portugal that includes anarchist elements, are shot dead by police officers.

* June 15, 1910 – The Bosnian anarchist Bogdan Žerajić attempts to assassinate the Governor of Bosnia and Herzegovian Marijan Varešanin, but failed and subsequently committed suicide.

* September 14, 1911 – Dmitri Bogrov shoots Russian prime minister Pyotr Stolypin

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, Пётр Аркадьевич Столыпин, p=pʲɵtr ɐrˈkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ stɐˈlɨpʲɪn; – ) was a Russian statesman who served as the third Prime Minister of Russia, prime minister and the Ministry ...

at the Kiev Opera House in the presence of Tsar Nicholas II and two of his daughters, Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana. Stolypin dies four days later, and Bogrov is hanged on September 25.

* November 12, 1912 – Anarchist Manuel Pardiñas shoots Spanish Prime Minister José Canalejas dead in front of a Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

bookstore. Pardiñas then immediately turns the gun on himself and commits suicide.

* March 18, 1913 – Alexandros Schinas shoots dead King George I of Greece

George I ( Greek: Γεώργιος Α΄, romanized: ''Geórgios I''; 24 December 1845 – 18 March 1913) was King of Greece from 30 March 1863 until his assassination on 18 March 1913.

Originally a Danish prince, George was born in Copenhage ...

while the monarch is on a walk near the White Tower of Thessaloniki

The White Tower of Thessaloniki ( ''Lefkós Pýrgos''; ; ) is a monument and museum on the waterfront of the city of Thessaloniki, capital of the Macedonia (Greece), region of Macedonia in northern Greece. The present tower replaced an old Byzantin ...

. Schinas is captured and tortured; he commits suicide on May 6 by jumping out the window of the gendarmerie, although there is speculation that he could have been thrown to his death.

* July 4, 1914 – A bomb being prepared for use at John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

's home at Tarrytown, New York

Tarrytown is a administrative divisions of New York#Village, village in the administrative divisions of New York#Town, town of Greenburgh, New York, Greenburgh in Westchester County, New York, Westchester County, New York (state), New York, Unit ...

explodes prematurely, killing three anarchists, Arthur Caron, Carl Hansen and Charles Berg,Morgan, Ted, ''Reds: McCarthyism in Twentieth-Century America'', New York: Random House, (2003), p. 58 and an innocent woman, Mary Chavez.

* October 13 and November 14, 1914 – ''Galleanists'' – radical followers of Luigi Galleani

Luigi Galleani (; 12 August 1861 – 4 November 1931) was an Italian insurrectionary anarchism, insurrectionary anarchist and Communism, communist best known for his advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", a strategy of political assassinations ...

– explode two bombs in New York City after police forcibly disperse a protest by anarchists and communists at John D. Rockefeller's home in Tarrytown.

* September 16, 1920 – The Wall Street bombing kills 38 and wounds 400 in the Manhattan Financial District. ''Galleanists'' are believed responsible, particularly Mario Buda, the group's principal bombmaker, although the crime remains officially unsolved.

* September 27, 1932 – A dynamite-filled package bomb left by ''Galleanists'' destroys Judge Webster Thayer's home in Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Massachusetts, second-most populous city in the U.S. state of Massachusetts and the list of United States cities by population, 113th most populous city in the United States. Named after Worcester ...

, injuring his wife and a housekeeper.''New York Times''"Bomb Menaces Life of Sacco Case Judge", September 27, 1932

accessed December 20, 2009Cannistraro, Philip V., and Meyer, Gerald, eds., ''The Lost World of Italian-American Radicalism: Politics, Labor, and Culture'', Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, (2003) p. 168 Judge Thayer had presided over the trials of ''Galleanists''

Sacco and Vanzetti

Nicola Sacco (; April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (; June 11, 1888 – August 23, 1927) were Italian immigrants and anarchists who were controversially convicted of murdering Alessandro Berardelli and Frederick Parm ...

.Avrich, Paul, ''Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background'', Princeton University Press (1991), pp. 58–60

See also

*Artivism

Artivism is a portmanteau word combining "art" and "activism", and is sometimes also referred to as "social artivism".

History

The term artivism in US English has its roots in a 1997 gathering of Chicano artists from East Los Angeles and t ...

* Civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active and professed refusal of a citizenship, citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders, or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be cal ...

* List of assassinations

This is a list of successful assassinations, sorted by location. For failed assassination attempts, see List of people who survived assassination attempts.

For the purposes of this article, an assassination is defined as the deliberate, premedit ...

* List of terrorist incidents

The following is a list of terrorist incidents that were not carried out by a state or its forces (see state terrorism and state-sponsored terrorism). Assassinations are presented in List of assassinations and unsuccessful attempts at List o ...

* V (comics)

V is the titular protagonist of the comic book series ''V for Vendetta'', created by Alan Moore and David Lloyd (comics), David Lloyd. He is a mysterious Anarchism, anarchist, vigilante, and Propaganda of the deed, freedom fighter who is easil ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * *Wallis, Glenn (2022).The Story of Anarchist Violence

" ''The Anarchist Library''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Anarchism And Violence History of anarchism Insurrectionary anarchism Issues in anarchism Violence