Amy Carter (netball Player) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

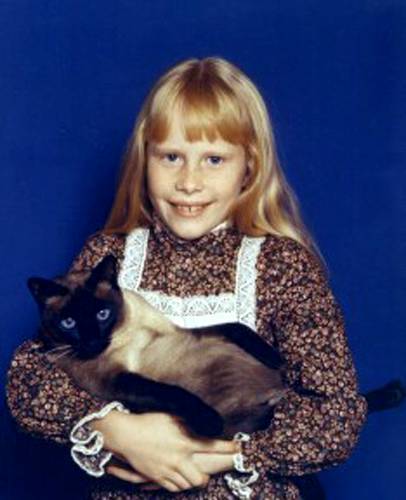

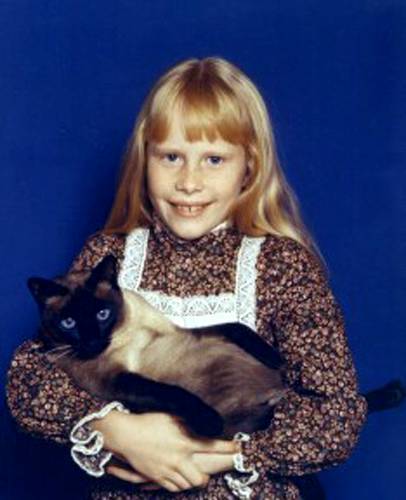

Amy Lynn Carter (born October 19, 1967) is the daughter of the 39th U.S. president

In January 1977, at the age of nine, Carter entered the White House, where she lived for four years. She was the subject of much media attention during this period, as young children had not lived in the White House since the early 1960s presidency of

In January 1977, at the age of nine, Carter entered the White House, where she lived for four years. She was the subject of much media attention during this period, as young children had not lived in the White House since the early 1960s presidency of  On February 21, 1977, during a

On February 21, 1977, during a

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

and his wife Rosalynn Carter. Carter entered the limelight as a child when she lived in the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

during the Carter presidency

Jimmy Carter's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 39th president of the United States began with Inauguration of Jimmy Carter, his inauguration on January 20, 1977, and ended on January 20, 1981. A History of the Democr ...

.

Early life and education

Amy Carter was born on October 19, 1967, inPlains, Georgia

Plains is a town in Sumter County, Georgia, United States. The population was 776 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Americus Micropolitan Statistical Area. Plains is best known as the birthplace and home of Jimmy Carter, the 39th president o ...

. She was raised in Plains until her father was elected governor and her family moved into the Georgia Governor's Mansion

The Governor's Mansion is the official home of the governor of the U.S. state of Georgia. The mansion is located at 391 West Paces Ferry Road NW, in the Tuxedo Park neighborhood of the affluent Buckhead district of Atlanta.

Construction

The ...

in Atlanta. In 1970

Events

January

* January 1 – Unix time epoch reached at 00:00:00 UTC.

* January 5 – The 7.1 Tonghai earthquake shakes Tonghai County, Yunnan province, China, with a maximum Mercalli intensity scale, Mercalli intensity of X (''Extrem ...

, her father was elected governor of Georgia

The governor of Georgia is the head of government of Georgia and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor also has a duty to enforce state laws, the power to either veto or approve bills passed by the Georgia Legisl ...

, and then in 1976

Events January

* January 3 – The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights enters into force.

* January 5 – The Pol Pot regime proclaims a new constitution for Democratic Kampuchea.

* January 11 – The 1976 Phila ...

, when she was nine, her father was elected President of the United States, and the family moved to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

.

Carter attended public schools in Washington during her four years in the White House; first Stevens Elementary School and then Rose Hardy Middle School

The District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) is the local public school system for the District of Columbia, in the United States.

It is distinct from the District of Columbia Public Charter Schools (DCPCS), which governs public charter ...

.

After her father's presidency, Carter moved to Atlanta and spent her senior year of high school at Woodward Academy in College Park, Georgia

College Park is a city in Fulton County, Georgia, Fulton and Clayton County, Georgia, Clayton counties, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States, adjacent to the southern boundary of the city of Atlanta. As of the 2020 United States Census, 20 ...

. She was a Senate page

A United States Senate Page (Senate Page or simply Page) is a high-school age teen serving the United States Senate in Washington, D.C. Pages are nominated by senators, usually from their home state, and perform a variety of tasks, such as delive ...

during the 1982 summer session. Carter attended Brown University

Brown University is a private research university in Providence, Rhode Island. Brown is the seventh-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, founded in 1764 as the College in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providenc ...

but was academically dismissed

Expulsion, also known as dismissal, withdrawal, or permanent exclusion (British English), is the permanent removal or banning of a student from a school, school district, college or university due to persistent violation of that institution's ru ...

in 1987, "for failing to keep up with her coursework". She later earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts

A Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) is a standard undergraduate degree for students for pursuing a professional education in the visual, fine or performing arts. It is also called Bachelor of Visual Arts (BVA) in some cases.

Background

The Bachelor ...

degree from the Memphis College of Art and a master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is an academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice.

in art history from Tulane University

Tulane University, officially the Tulane University of Louisiana, is a private university, private research university in New Orleans, Louisiana. Founded as the Medical College of Louisiana in 1834 by seven young medical doctors, it turned into ...

in New Orleans in 1996.

Life in the White House

In January 1977, at the age of nine, Carter entered the White House, where she lived for four years. She was the subject of much media attention during this period, as young children had not lived in the White House since the early 1960s presidency of

In January 1977, at the age of nine, Carter entered the White House, where she lived for four years. She was the subject of much media attention during this period, as young children had not lived in the White House since the early 1960s presidency of John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

(and would not again do so after the Carter presidency until the inauguration of Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

, in January 1993, when Chelsea moved in.)

While Carter was in the White House, she had a Siamese cat named Misty Malarky Ying Yang, which was the last cat to occupy the White House until Socks, owned by Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

. Carter also was given an elephant from Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

from an immigrant; the animal was given to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C.

Carter roller-skated through the White House's East Room and had a treehouse on the South Lawn. When she invited friends over for slumber parties in her tree house, Secret Service

A secret service is a government agency, intelligence agency, or the activities of a government agency, concerned with the gathering of intelligence data. The tasks and powers of a secret service can vary greatly from one country to another. For ...

agents monitored the event from the ground.

Mary Prince

Mary Prince (c. 1 October 1788 – after 1833) was a British abolitionist and autobiographer, born in Bermuda to a slave family of African descent. After being sold a number of times, and being moved around the Caribbean, she was brought to Engl ...

(an African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

woman convicted of murder, and later exonerated and pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the ju ...

ed) acted as her nanny for most of the period from 1971 until Jimmy Carter's presidency ended, having begun in that position through a prison release program in Georgia.

Carter did not receive the "hands off" treatment that most of the media later afforded to Chelsea Clinton

Chelsea Victoria Clinton (born February 27, 1980) is an American writer and global health advocate. She is the only child of former U.S. President Bill Clinton and former U.S. Secretary of State and 2016 presidential candidate Hillary Clinton ...

. President Carter mentioned his daughter during a 1980 debate with Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

, when he said he had asked her what the most important issue in that election was and she said, "the control of nuclear arms".

Once, when asked by a reporter whether she had any message for the children of America, she looked at the reporter square in the eyes, thought for a few moments, and said, "No."

On February 21, 1977, during a

On February 21, 1977, during a White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

state dinner for Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau

Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau ( , ; October 18, 1919 – September 28, 2000), also referred to by his initials PET, was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 15th prime minister of Canada

The prime mini ...

, nine-year-old Amy was seen reading two books, ''Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator

''Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator'' is a children's literature, children's book by British author Roald Dahl. It is the sequel to ''Charlie and the Chocolate Factory'', continuing the story of young List of Charlie and the Chocolate Facto ...

'' and ''The Story of the Gettysburg Address'', while the formal toasts by her father and Trudeau were exchanged. Some saw it as an affront to foreign guests.

Activism

Amy Carter later became known for her political activism. She participated insit-in

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

s and protests during the 1980s and early 1990s that were aimed at changing U.S. foreign policy towards South African apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

and Central America. Along with activist Abbie Hoffman

Abbot Howard "Abbie" Hoffman (November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989) was an American political and social activist who co-founded the Youth International Party ("Yippies") and was a member of the Chicago Seven. He was also a leading proponen ...

and 13 others, she was arrested during a 1986 demonstration at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

The University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst, UMass) is a public research university in Amherst, Massachusetts and the sole public land-grant university in Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Founded in 1863 as an agricultural college, it ...

for protesting CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

recruitment there. She was acquitted of all charges in a well-publicized trial in Northampton, Massachusetts. Attorney Leonard Weinglass

Leonard Irving Weinglass (August 27, 1933 – March 23, 2011) was a U.S. criminal defense lawyer and constitutional law advocate, best known for his defense of participants in the 1960s counterculture. He was admitted to the bar in New Jer ...

, who defended Abbie Hoffman in the Chicago Seven trial in the 1960s, utilized the necessity

Necessary or necessity may refer to:

* Need

** An action somebody may feel they must do

** An important task or essential thing to do at a particular time or by a particular moment

* Necessary and sufficient condition, in logic, something that is ...

defense, successfully arguing that because the CIA was involved in criminal activity in Central America and other hotspots, preventing it from recruiting on campus was equivalent to trespassing in a burning building.

Personal life

Amy Carter illustrated '' The Little Baby Snoogle-Fleejer'', her father's book for children, published in 1995. In September 1996, Carter married computer consultant James Gregory Wentzel, whom she met while attending Tulane. Wentzel was a manager at Chapter Eleven, an Atlanta bookstore, where Carter worked part time. They have a son, Hugo James Wentzel. In 2005, the couple divorced. In 2007, Carter married John Joseph "Jay" Kelly. They have a son, Errol Carter Kelly. Since the late 1990s, Carter has maintained a low profile, neither participating in public protests nor granting interviews (she gave an interview on ''Late Night with David Letterman

''Late Night with David Letterman'' is an American late-night talk show hosted by David Letterman on NBC, the first iteration of the ''Late Night'' franchise. It premiered on February 1, 1982, and was produced by Letterman's production company ...

'' in 1982). She is a member of the board of counselors of the Carter Center

The Carter Center is a nongovernmental, not-for-profit organization founded in 1982 by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter. He and his wife Rosalynn Carter partnered with Emory University just after his defeat in the 1980 United States presidenti ...

, which advocates for human rights

Human rights are Morality, moral principles or Social norm, normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for ce ...

and diplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. 1 ...

; it was established by her father.

In popular culture

'' Little House on the Prairie'' actress Alison Arngrim impersonated Carter on the 1978Laff Records

Laff Records was a small American independent record label specializing in comedy and party records originating on the West Coast of the United States during the 1970s. Amongst their artists were Richard Pryor, Redd Foxx, LaWanda Page, George Ca ...

comedy album ''Heeere's Amy''.

See also

* List of children of presidents of the United StatesReferences

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Carter, Amy 1967 births 20th-century American people 20th-century American women 21st-century American women American political activists Brown University alumni Carter family Children of presidents of the United States Children of presidents Living people Politicians from Atlanta People from Plains, Georgia Tulane University School of Liberal Arts alumni Woodward Academy alumni Memphis College of Art alumni