Allied Invasion Of France on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the

"Overlord" was the name assigned to the establishment of a large-scale

"Overlord" was the name assigned to the establishment of a large-scale

The

The

After the disastrous

After the disastrous

Training exercises for the Overlord landings took place as early as July 1943. As the nearby beach resembled the planned Normandy landing-site, the town of Slapton in Devon, was evacuated in December 1943, and taken over by the armed forces as a site for training exercises that included the use of landing craft and the management of beach obstacles. A

Training exercises for the Overlord landings took place as early as July 1943. As the nearby beach resembled the planned Normandy landing-site, the town of Slapton in Devon, was evacuated in December 1943, and taken over by the armed forces as a site for training exercises that included the use of landing craft and the management of beach obstacles. A

The invasion planners specified a set of conditions regarding the timing of the invasion, deeming only a few days in each month suitable. A full moon was desirable, as it would provide illumination for aircraft pilots and have the highest tides. The Allies wanted to schedule the landings for shortly before dawn, midway between low and high tide, with the tide coming in. This would improve the visibility of obstacles the enemy had placed on the beach while minimising the amount of time the men had to spend exposed in the open. Specific criteria were also set for wind speed, visibility, and cloud cover. Eisenhower had tentatively selected 5 June as the date for the assault; however, on 4 June, conditions were clearly unsuitable for a landing, as high winds and heavy seas made it impossible to launch landing craft, and low clouds would prevent aircraft from finding their targets.

By the evening of 4 June, the Allied meteorological team, headed by Group Captain

The invasion planners specified a set of conditions regarding the timing of the invasion, deeming only a few days in each month suitable. A full moon was desirable, as it would provide illumination for aircraft pilots and have the highest tides. The Allies wanted to schedule the landings for shortly before dawn, midway between low and high tide, with the tide coming in. This would improve the visibility of obstacles the enemy had placed on the beach while minimising the amount of time the men had to spend exposed in the open. Specific criteria were also set for wind speed, visibility, and cloud cover. Eisenhower had tentatively selected 5 June as the date for the assault; however, on 4 June, conditions were clearly unsuitable for a landing, as high winds and heavy seas made it impossible to launch landing craft, and low clouds would prevent aircraft from finding their targets.

By the evening of 4 June, the Allied meteorological team, headed by Group Captain

Alarmed by the raids on

Alarmed by the raids on

The craft bearing the

The craft bearing the  Omaha, the most heavily defended sector, was assigned to the

Omaha, the most heavily defended sector, was assigned to the  Landings of infantry at Juno were delayed because of rough seas, and the men arrived ahead of their supporting armour, suffering many casualties while disembarking. Most of the offshore bombardment had missed the German defences. In spite of these difficulties, the Canadians quickly cleared the beach and created two exits to the villages above. Delays in taking

Landings of infantry at Juno were delayed because of rough seas, and the men arrived ahead of their supporting armour, suffering many casualties while disembarking. Most of the offshore bombardment had missed the German defences. In spite of these difficulties, the Canadians quickly cleared the beach and created two exits to the villages above. Delays in taking

Fighting in the Caen area versus the 21st Panzer, the 12th SS Panzer Division ''Hitlerjugend'' and other units soon reached a stalemate. During

Fighting in the Caen area versus the 21st Panzer, the 12th SS Panzer Division ''Hitlerjugend'' and other units soon reached a stalemate. During

Eisenhower took direct command of all Allied ground forces on 1 September. Concerned about German counter-attacks and the limited materiel arriving in France, he decided to continue operations on a broad front rather than attempting narrow thrusts. The linkup of the Normandy forces with the Allied forces in southern France occurred on 12 September as part of the drive to the Siegfried Line. On 17 September, Montgomery launched Operation Market Garden, an unsuccessful attempt by Anglo-American airborne troops to capture bridges in the Netherlands to allow ground forces to cross the Rhine into Germany. The Allied advance slowed due to German resistance and the lack of supplies (especially fuel). On 16 December the Germans launched the Ardennes Offensive, also known as the Battle of the Bulge, the last major German offensive of the war on the Western Front. A series of successful Soviet actions began with the Vistula–Oder Offensive on 12 January. Death of Adolf Hitler, Hitler committed suicide on 30 April as Soviet troops neared his ''Führerbunker'' in Berlin, and Germany surrendered on 7 May 1945.

The Normandy landings were the largest seaborne invasion in history, with nearly 5,000 landing and assault craft, 289 escort vessels, and 277 minesweepers. The opening of another front in western Europe was a tremendous psychological blow for Germany's military, who feared a repetition of the two-front war of World War I. The Normandy landings also heralded the start of the "race for Europe" between the Soviet forces and the Western powers, which some historians consider to be the Origins of the Cold War, start of the Cold War.

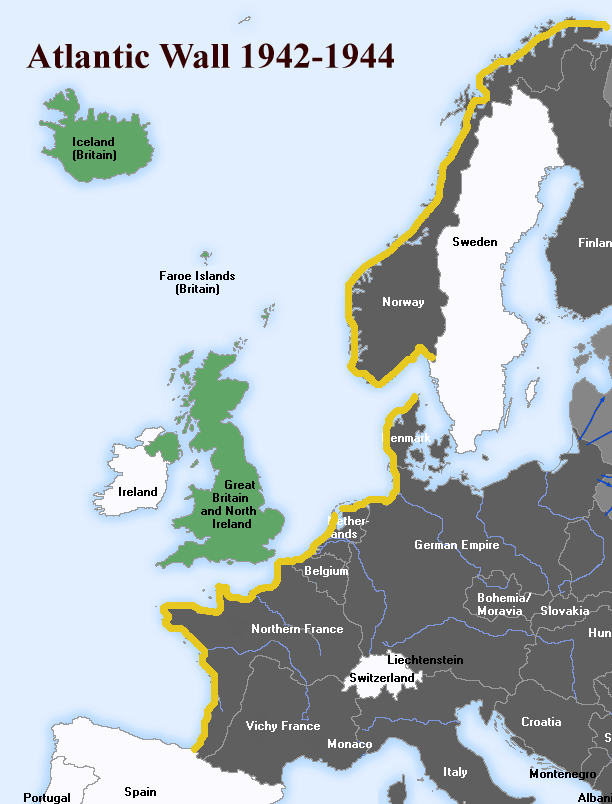

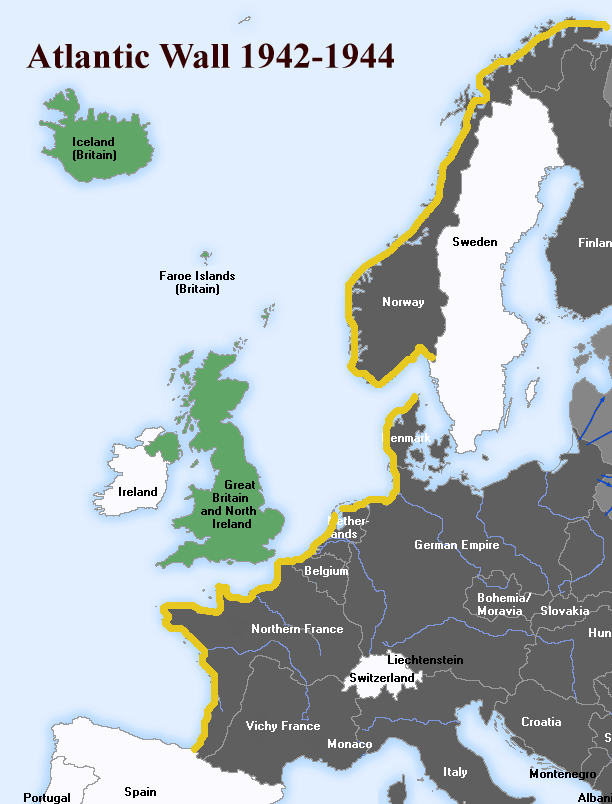

Victory in Normandy stemmed from several factors. German preparations along the Atlantic Wall were only partially finished; shortly before D-Day Rommel reported that construction was only 18 per cent complete in some areas as resources were diverted elsewhere. The deceptions undertaken in Operation Fortitude were successful, leaving the Germans obliged to defend a huge stretch of coastline. The Allies achieved and maintained air superiority, which meant that the Germans were unable to make observations of the preparations underway in Britain and were unable to interfere via bomber attacks. Transport infrastructure in France was severely disrupted by Allied bombers and the French Resistance, making it difficult for the Germans to bring up reinforcements and supplies. Much of the opening artillery barrage was off-target or not concentrated enough to have any impact, but the specialised armour worked well except on Omaha, providing close artillery support for the troops as they disembarked onto the beaches. The indecisiveness and overly complicated command structure of the German high command was also a factor in the Allied success.

Eisenhower took direct command of all Allied ground forces on 1 September. Concerned about German counter-attacks and the limited materiel arriving in France, he decided to continue operations on a broad front rather than attempting narrow thrusts. The linkup of the Normandy forces with the Allied forces in southern France occurred on 12 September as part of the drive to the Siegfried Line. On 17 September, Montgomery launched Operation Market Garden, an unsuccessful attempt by Anglo-American airborne troops to capture bridges in the Netherlands to allow ground forces to cross the Rhine into Germany. The Allied advance slowed due to German resistance and the lack of supplies (especially fuel). On 16 December the Germans launched the Ardennes Offensive, also known as the Battle of the Bulge, the last major German offensive of the war on the Western Front. A series of successful Soviet actions began with the Vistula–Oder Offensive on 12 January. Death of Adolf Hitler, Hitler committed suicide on 30 April as Soviet troops neared his ''Führerbunker'' in Berlin, and Germany surrendered on 7 May 1945.

The Normandy landings were the largest seaborne invasion in history, with nearly 5,000 landing and assault craft, 289 escort vessels, and 277 minesweepers. The opening of another front in western Europe was a tremendous psychological blow for Germany's military, who feared a repetition of the two-front war of World War I. The Normandy landings also heralded the start of the "race for Europe" between the Soviet forces and the Western powers, which some historians consider to be the Origins of the Cold War, start of the Cold War.

Victory in Normandy stemmed from several factors. German preparations along the Atlantic Wall were only partially finished; shortly before D-Day Rommel reported that construction was only 18 per cent complete in some areas as resources were diverted elsewhere. The deceptions undertaken in Operation Fortitude were successful, leaving the Germans obliged to defend a huge stretch of coastline. The Allies achieved and maintained air superiority, which meant that the Germans were unable to make observations of the preparations underway in Britain and were unable to interfere via bomber attacks. Transport infrastructure in France was severely disrupted by Allied bombers and the French Resistance, making it difficult for the Germans to bring up reinforcements and supplies. Much of the opening artillery barrage was off-target or not concentrated enough to have any impact, but the specialised armour worked well except on Omaha, providing close artillery support for the troops as they disembarked onto the beaches. The indecisiveness and overly complicated command structure of the German high command was also a factor in the Allied success.

Allied forces in northern France reported the capture of 47,000 Germans in June, 36,000 in July, and 150,000 in August, a total of 233,000 for the three months of Overlord.''SHAEF Weekly Intelligence Summary, No.51'', w.e. March 11 PART I LAND Section H, Miscellaneous 3 Allied Achievements in the West. Around 80,000 German soldiers are buried in Normandy, although this figure does include an unreported number of Germans who died prior to the battle and those who died in captivity after the end of the fighting.

German forces in France reported losses of 158,930 men between D-Day and 14 August, just before the start of Operation Dragoon in Southern France. In action at the Falaise pocket, 50,000 men were lost, of whom 10,000 were killed and 40,000 captured. Sources vary on the total German casualties. Niklas Zetterling notes that OB West's figures for summer 1944 in the west (thus including in its scope Operation Dragoon in southern France) amounted to 289,000: 23,019 killed, 67,060 wounded, and 198,616 missing. He states that the record is generally reliable, but also that it might have underestimated losses in some places, such as Cherbourg. Zetterling goes on to estimate specifically German army casualties in the Normandy region specifically from June 6 to August as 210,000; however, he also notes that "the Germans most likely suffered further manpower losses when air or naval bases were overrun. On this no figures have been available for this study." Other sources arrive at higher estimates: 400,000 (200,000 killed or wounded and a further 200,000 captured), 500,000 (290,000 killed or wounded, 210,000 captured), to 530,000 in total.

There are no exact figures regarding German tank losses in Normandy. Approximately 2,300 tanks and assault guns were committed to the battle, of which only 100 to 120 crossed the Seine at the end of the campaign. While German forces reported only 481 tanks destroyed between D-day and 31 July, research conducted by Operations research, No. 2 Operational Research Section of 21st Army Group indicates that the Allies destroyed around 550 tanks in June and July and another 500 in August, for a total of 1,050 tanks destroyed, including 100 destroyed by aircraft. Luftwaffe losses amounted to 2,127 aircraft. By the end of the Normandy campaign, 55 German divisions (42 infantry and 13 panzer) had been rendered combat ineffective; seven of these were disbanded. By September, OB West had only 13 infantry divisions, 3 panzer divisions, and 2 panzer brigades rated as combat effective.

Allied forces in northern France reported the capture of 47,000 Germans in June, 36,000 in July, and 150,000 in August, a total of 233,000 for the three months of Overlord.''SHAEF Weekly Intelligence Summary, No.51'', w.e. March 11 PART I LAND Section H, Miscellaneous 3 Allied Achievements in the West. Around 80,000 German soldiers are buried in Normandy, although this figure does include an unreported number of Germans who died prior to the battle and those who died in captivity after the end of the fighting.

German forces in France reported losses of 158,930 men between D-Day and 14 August, just before the start of Operation Dragoon in Southern France. In action at the Falaise pocket, 50,000 men were lost, of whom 10,000 were killed and 40,000 captured. Sources vary on the total German casualties. Niklas Zetterling notes that OB West's figures for summer 1944 in the west (thus including in its scope Operation Dragoon in southern France) amounted to 289,000: 23,019 killed, 67,060 wounded, and 198,616 missing. He states that the record is generally reliable, but also that it might have underestimated losses in some places, such as Cherbourg. Zetterling goes on to estimate specifically German army casualties in the Normandy region specifically from June 6 to August as 210,000; however, he also notes that "the Germans most likely suffered further manpower losses when air or naval bases were overrun. On this no figures have been available for this study." Other sources arrive at higher estimates: 400,000 (200,000 killed or wounded and a further 200,000 captured), 500,000 (290,000 killed or wounded, 210,000 captured), to 530,000 in total.

There are no exact figures regarding German tank losses in Normandy. Approximately 2,300 tanks and assault guns were committed to the battle, of which only 100 to 120 crossed the Seine at the end of the campaign. While German forces reported only 481 tanks destroyed between D-day and 31 July, research conducted by Operations research, No. 2 Operational Research Section of 21st Army Group indicates that the Allies destroyed around 550 tanks in June and July and another 500 in August, for a total of 1,050 tanks destroyed, including 100 destroyed by aircraft. Luftwaffe losses amounted to 2,127 aircraft. By the end of the Normandy campaign, 55 German divisions (42 infantry and 13 panzer) had been rendered combat ineffective; seven of these were disbanded. By September, OB West had only 13 infantry divisions, 3 panzer divisions, and 2 panzer brigades rated as combat effective.

The beaches of Normandy are still known by their invasion code names. Significant places have plaques, memorials, or small museums, and guide books and maps are available. Some of the German strong points remain preserved; Pointe du Hoc, in particular, is little changed from 1944. The remains of Mulberry harbour B still sits in the sea at Arromanches. Several List of military cemeteries in Normandy, large cemeteries in the area serve as the final resting place for many of the Allied and German soldiers killed in the Normandy campaign.

Above the English Channel on a bluff at Omaha Beach, the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial has hosted numerous visitors each year. The site covers and contains the remains of 9,388 American military dead, most of whom were killed during the invasion of Normandy and ensuing military operations in World War II. Included are graves of Army Air Corps crews shot down over France as early as 1942 and four American women.

The beaches of Normandy are still known by their invasion code names. Significant places have plaques, memorials, or small museums, and guide books and maps are available. Some of the German strong points remain preserved; Pointe du Hoc, in particular, is little changed from 1944. The remains of Mulberry harbour B still sits in the sea at Arromanches. Several List of military cemeteries in Normandy, large cemeteries in the area serve as the final resting place for many of the Allied and German soldiers killed in the Normandy campaign.

Above the English Channel on a bluff at Omaha Beach, the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial has hosted numerous visitors each year. The site covers and contains the remains of 9,388 American military dead, most of whom were killed during the invasion of Normandy and ensuing military operations in World War II. Included are graves of Army Air Corps crews shot down over France as early as 1942 and four American women.

Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

) with the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and ...

(Operation Neptune). A 1,200-plane airborne assault

Airborne forces are Ground warfare, ground combat units airlift, carried by aircraft and airdropped into battle zones, typically by parachute drop. Parachute-qualified infantry and support personnel serving in airborne units are also known as par ...

preceded an amphibious assault

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducte ...

involving more than 5,000 vessels. Nearly 160,000 troops crossed the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

on 6 June, and more than two million Allied troops were in France by the end of August.

The decision to undertake cross-channel landings in 1944 was made at the Trident Conference

The Third Washington Conference (Code name, codenamed Trident) was held in Washington, D.C., Washington, D.C from May 12 to May 25, 1943. It was a World War II Military strategy, strategic meeting between the heads of government of the United Kin ...

in Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

in May 1943. American General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

was appointed commander of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF; ) was the headquarters of the Commander of Allies of World War II, Allied forces in northwest Europe, from late 1943 until the end of World War II. US General Dwight D. Eisenhower was the ...

, and British General Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

was named commander of the 21st Army Group

The 21st Army Group was a British headquarters formation formed during the Second World War. It controlled two field armies and other supporting units, consisting primarily of the British Second Army and the First Canadian Army. Established ...

, which comprised all the land forces involved in the operation. The Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

coast in northwestern France was chosen as the site of the landings, with the Americans assigned to land at sectors codenamed Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

and Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

, the British at Sword

A sword is an edged and bladed weapons, edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter ...

and Gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

, and the Canadians at Juno

Juno commonly refers to:

*Juno (mythology), the Roman goddess of marriage and queen of the gods

* ''Juno'' (film), the 2007 film

Juno may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Fictional characters

*Juno, a character in the book ''Juno of ...

. To meet the conditions expected on the Normandy beachhead, special technology was developed, including two artificial ports called Mulberry harbours

The Mulberry harbours were two temporary portable harbours developed by the Admiralty (United Kingdom), British Admiralty and War Office during the Second World War to facilitate the rapid offloading of cargo onto beaches during the Allies of ...

and an array of specialised tanks nicknamed Hobart's Funnies

Hobart's Funnies is the nickname given to a number of specialist armoured fighting vehicles derived from tanks operated during the Second World War by units of the 79th Armoured Division of the British Army or by specialists from the Royal En ...

. In the months leading up to the landings, the Allies conducted Operation Bodyguard

Operation Bodyguard was the code name for a World War II military deception, deception strategy employed by the Allies of World War II, Allied states before the 1944 invasion of northwest Europe. Bodyguard set out an overall stratagem for mislea ...

, a substantial military deception

Military deception (MILDEC) is an attempt by a military unit to gain an advantage during warfare by misleading adversary decision makers into taking action or inaction that creates favorable conditions for the deceiving force. This is usually ...

that used electronic and visual misinformation to mislead the Germans as to the date and location of the main Allied landings. Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

placed Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel (; 15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944), popularly known as The Desert Fox (, ), was a German '' Generalfeldmarschall'' (field marshal) during World War II. He served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of ...

in charge of developing fortifications all along Hitler's proclaimed Atlantic Wall

The Atlantic Wall () was an extensive system of coastal defence and fortification, coastal defences and fortifications built by Nazi Germany between 1942 and 1944 along the coast of continental Europe and Scandinavia as a defense (military), d ...

in anticipation of landings in France.

The Allies failed to accomplish their objectives for the first day, but gained a tenuous foothold that they gradually expanded when they captured the port at Cherbourg

Cherbourg is a former Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French departments of France, department of Manche. It was merged into the com ...

on 26 June and the city of Caen

Caen (; ; ) is a Communes of France, commune inland from the northwestern coast of France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Calvados (department), Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inha ...

on 21 July. A failed counterattack by German forces in response to Allied advances on 7 August left 50,000 soldiers of the German 7th Army trapped in the Falaise pocket

The Falaise pocket or battle of the Falaise pocket (; 12–21 August 1944) was the decisive engagement of the Battle of Normandy in the Second World War. Allied forces formed a pocket around Falaise, Calvados, in which German Army Group B, c ...

by 19 August. The Allies launched a second invasion from the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

of southern France (code-named Operation Dragoon

Operation Dragoon (initially Operation Anvil), known as Débarquement de Provence in French ("Provence Landing"), was the code name for the landing operation of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Provence (Southern France) on 15Augu ...

) on 15 August, and the Liberation of Paris

The liberation of Paris () was a battle that took place during World War II from 19 August 1944 until the German garrison surrendered the French capital on 25 August 1944. Paris had been occupied by Nazi Germany since the signing of the Armisti ...

followed on 25 August. German forces retreated east across the Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plat ...

on 30 August 1944, marking the close of Operation Overlord.

Preparations for D-Day

In June 1940, Germany's leaderAdolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

had triumphed in what he called "the most famous victory in history"—the fall of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Net ...

. British craft evacuated to England over 338,000 Allied troops trapped along the northern coast of France (including much of the British Expeditionary Force) in the Dunkirk evacuation

The Dunkirk evacuation, codenamed Operation Dynamo and also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, or just Dunkirk, was the evacuation of more than 338,000 Allied soldiers during the Second World War from the beaches and harbour of Dunkirk, in the ...

(27 May to 4 June). British planners reported to Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

on 4 October that even with the help of other Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

countries and the United States, it would not be possible to regain a foothold in continental Europe in the near future. After the Axis invaded the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along a ...

in June 1941, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

began pressing for a second front

The Western Front was a military theatre of World War II encompassing Denmark, Norway, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. The Italian front is considered a separate but related theatre. The Wester ...

in Western Europe. Churchill declined because he felt that even with American help the British did not have adequate forces to do it, and he wished to avoid costly frontal assaults such as those that had occurred at the Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

* Somme, Queensland, Australia

* Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), ...

and Passchendaele in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

Two temporary plans code-named Operation Roundup and Operation Sledgehammer

Operation Sledgehammer was an Allies of World War II, Allied plan for a cross-English Channel, Channel invasion of Europe during World War II, as the first step in helping to reduce pressure on the Soviet Red Army by establishing a Western Front ( ...

were put forward for 1942–43, but neither was deemed by the British to be practical or likely to succeed. Instead, the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

expanded their activity in the Mediterranean, launching Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

, an invasion of French North Africa

French North Africa (, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is a term often applied to the three territories that were controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In contrast to French ...

, in November 1942, the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as the Battle of Sicily and Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allies of World War II, Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis p ...

in July 1943, and Allied invasion of Italy

The Allied invasion of Italy was the Allies of World War II, Allied Amphibious warfare, amphibious landing on mainland Italy that took place from 3 September 1943, during the Italian campaign (World War II), Italian campaign of World War II. T ...

in September. These campaigns provided the troops with valuable experience in amphibious warfare

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conduc ...

. Those attending the Trident Conference

The Third Washington Conference (Code name, codenamed Trident) was held in Washington, D.C., Washington, D.C from May 12 to May 25, 1943. It was a World War II Military strategy, strategic meeting between the heads of government of the United Kin ...

in Washington in May 1943 took the decision to launch a cross-Channel invasion within the next year. Churchill favoured making the main Allied thrust into Germany from the Mediterranean theatre, but the Americans, who were providing the bulk of the men and equipment, over-ruled him. British Lieutenant-General Frederick E. Morgan

Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Edgworth Morgan, (5 February 1894 – 19 March 1967) was a senior officer of the British Army who fought in both world wars. He is best known as the chief of staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), the o ...

was appointed Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), to begin detailed planning.

The initial plans were constrained by the number of landing craft

Landing craft are small and medium seagoing watercraft, such as boats and barges, used to convey a landing force (infantry and vehicles) from the sea to the shore during an amphibious assault. The term excludes landing ships, which are larger. ...

, most of which were already committed in the Mediterranean and in the Pacific. In part because of lessons learned in the Dieppe Raid

Operation Jubilee or the Dieppe Raid (19 August 1942) was a disastrous Allied amphibious attack on the German-occupied port of Dieppe in northern France, during the Second World War. Over 6,050 infantry, predominantly Canadian, supported by a ...

of 19 August 1942, the Allies decided not to directly assault a heavily defended French seaport in their first landing. The failure at Dieppe also highlighted the need for adequate artillery and air support, particularly close air support

Close air support (CAS) is defined as aerial warfare actions—often air-to-ground actions such as strafes or airstrikes—by military aircraft against hostile targets in close proximity to friendly forces. A form of fire support, CAS requires ...

, and specialised ships able to travel extremely close to shore. The short operating range of British aircraft such as the Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft that was used by the Royal Air Force and other Allies of World War II, Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. It was the only British fighter produced conti ...

and Hawker Typhoon

The Hawker Typhoon was a British single-seat fighter-bomber, produced by Hawker Aircraft. It was intended to be a medium-high altitude interceptor aircraft, interceptor, as a replacement for the Hawker Hurricane, but several design problems we ...

greatly limited the number of potential landing-sites, as comprehensive air support depended upon having planes overhead for as long as possible. Morgan considered four sites for the landings: Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

, the Cotentin Peninsula

The Cotentin Peninsula (, ; ), also known as the Cherbourg Peninsula, is a peninsula in Normandy that forms part of the northwest coast of France. It extends north-westward into the English Channel, towards Great Britain. To its west lie the Gu ...

, Normandy, and the Pas de Calais

The Strait of Dover or Dover Strait, historically known as the Dover Narrows, is the strait at the narrowest part of the English Channel, marking the boundary between the Channel and the North Sea, and separating Great Britain from continental ...

. As Brittany and Cotentin are peninsulas, the Germans could have cut off the Allied advance at a relatively narrow isthmus

An isthmus (; : isthmuses or isthmi) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea count ...

, so these sites were rejected.

The Pas de Calais, the closest point in continental Europe to Britain, was the location of launch sites for V-1 and V-2 rocket

The V2 (), with the technical name ''Aggregat (rocket family), Aggregat-4'' (A4), was the world's first long-range missile guidance, guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was developed during the S ...

s, then still under development. The Germans regarded it as the most likely initial landing zone and accordingly made it the most heavily fortified region; however, it offered the Allies few opportunities for expansion as the area is bounded by numerous rivers and canals. On the other hand, landings on a broad front in Normandy would permit simultaneous threats against the port of Cherbourg

Cherbourg is a former Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French departments of France, department of Manche. It was merged into the com ...

, coastal ports further west in Brittany, and an overland attack towards Paris and eventually into Germany. The Allies therefore chose Normandy as the landing site. The most serious drawback of the Normandy coast – the lack of port facilities – would be overcome through the development and deployment of artificial harbours.

The COSSAC staff planned to begin the invasion on 1 May 1944. The initial draft of the plan was accepted at the Quebec Conference in August 1943. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed commander of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF; ) was the headquarters of the Commander of Allies of World War II, Allied forces in northwest Europe, from late 1943 until the end of World War II. US General Dwight D. Eisenhower was the ...

(SHAEF). General Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

was named commander of the 21st Army Group

The 21st Army Group was a British headquarters formation formed during the Second World War. It controlled two field armies and other supporting units, consisting primarily of the British Second Army and the First Canadian Army. Established ...

, which comprised all of the land forces involved in the invasion. On 31 December 1943, Eisenhower and Montgomery first saw the COSSAC plan, which proposed amphibious landings by three divisions

Division may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

* Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting of 10,000 t ...

, with two more divisions in support. The two generals immediately insisted on expanding the scale of the initial invasion to five divisions, with airborne descents by three additional divisions, to allow operations on a wider front and to speed up the capture of the port at Cherbourg. This significant expansion required the acquisition of additional landing craft, which caused the invasion to be delayed by a month until June 1944. Eventually the Allies committed 39 divisions to the Battle of Normandy: 22 American, 12 British, 3 Canadian, 1 Polish, and 1 French, totalling over a million troops.

Allied invasion plan

"Overlord" was the name assigned to the establishment of a large-scale

"Overlord" was the name assigned to the establishment of a large-scale lodgement

A lodgement or lodgment is an enclave, taken and defended by force of arms against determined opposition, made by increasing the size of a bridgehead, beachhead, or airhead into a substantial defended area, at least the rear parts of which ...

on the Continent. The first phase, the amphibious invasion and establishment of a secure foothold, was code-named Operation Neptune

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

and is often referred to as "D-Day". To gain the required air superiority needed to ensure a successful invasion, the Allies launched a strategic bombing campaign (codenamed Pointblank

Point-blank range is any distance over which a certain firearm or gun can hit a target without the need to elevate the barrel to compensate for bullet drop, i.e. the gun can be pointed horizontally at the target. For targets beyond-blank range, ...

) to target German aircraft-production, fuel supplies, and airfields. Under the Transport Plan, communications infrastructure and road and rail links were bombed to cut off the north of France and to make it more difficult to bring up reinforcements. These attacks were widespread so as to avoid revealing the exact location of the invasion. Elaborate deceptions were planned to prevent the Germans from determining the timing and location of the invasion.

The coastline of Normandy was divided into seventeen sectors, with code-names using a spelling alphabet

A spelling alphabet (#Terminology, also called by various other names) is a set of words used to represent the Letter (alphabet), letters of an alphabet in Speech, oral communication, especially over a two-way radio or telephone. The words chosen t ...

—from Able, west of Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

, to Roger on the east flank of Sword

A sword is an edged and bladed weapons, edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter ...

. Eight further sectors were added when the invasion was extended to include Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

on the Cotentin Peninsula. Sectors were further subdivided into beaches identified by the colours Green, Red, and White.

Allied planners envisaged preceding the sea-borne landings with airborne drops: near Caen on the eastern flank to secure the Orne River

The Orne () is a river in Normandy, within northwestern France. It is long. It discharges into the English Channel at the port of Ouistreham. Its source is in Aunou-sur-Orne, east of Sées. Its main tributaries are the Odon and the Rouvre.

...

bridges, and north of Carentan

Carentan () is a small rural town near the north-eastern base of the French Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy in north-western France, with a population of about 6,000. It is a former commune in the Manche department. On 1 January 2016, it was m ...

on the western flank. The initial goal was to capture Carentan, Isigny, Bayeux

Bayeux (, ; ) is a commune in the Calvados department in Normandy in northwestern France.

Bayeux is the home of the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts the events leading up to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. It is also known as the fir ...

, and Caen. The Americans, assigned to land at Utah and Omaha, were to cut off the Cotentin Peninsula and capture the port facilities at Cherbourg. The British at Sword and Gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

, and the Canadians at Juno

Juno commonly refers to:

*Juno (mythology), the Roman goddess of marriage and queen of the gods

* ''Juno'' (film), the 2007 film

Juno may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Fictional characters

*Juno, a character in the book ''Juno of ...

, were to capture Caen and form a front line from Caumont-l'Éventé

Caumont-l'Éventé () is a former commune in the Calvados department in northwestern France. On 1 January 2017, it was merged into the new commune Caumont-sur-Aure.Falaise

Falaise may refer to:

Places

* Falaise, Ardennes, commune in France

* Falaise, Calvados, commune in France

** The Falaise pocket, site of a battle in the Second World War

* La Falaise, commune in the Yvelines ''département'', France

* The Falaise ...

. A secure lodgement would be established and an attempt made to hold all territory captured north of the Avranches

Avranches (; ) is a commune in the Manche department, and the region of Normandy, northwestern France. It is a subprefecture of the department. The inhabitants are called ''Avranchinais''.

History Middle Ages

By the end of the Roman period, th ...

-Falaise line during the first three weeks. The Allied armies would then swing left to advance towards the River Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres p ...

.

The invasion fleet, led by Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay

Admiral Sir Bertram Home Ramsay, KCB, KBE, MVO (20 January 1883 – 2 January 1945) was a Royal Navy officer. He commanded the destroyer during the First World War. In the Second World War, he was responsible for the Dunkirk evacuation in 1 ...

, was split into the Western Naval Task Force (under Admiral Alan Kirk

Alan Goodrich Kirk (October 30, 1888 – October 15, 1963) was a United States Navy admiral during World War II who most notably served as the senior naval commander during the Normandy landings. After the war he embarked on a diplomatic career ...

) supporting the American sectors and the Eastern Naval Task Force (under Admiral Sir Philip Vian

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Philip Louis Vian, & Two Bars (15 June 1894 – 27 May 1968) was a Royal Navy officer who served in both World Wars.

Vian specialised in naval gunnery from the end of the First World War and received several ap ...

) in the British and Canadian sectors. The American forces of the First Army, led by Lieutenant General Omar Bradley

Omar Nelson Bradley (12 February 1893 – 8 April 1981) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army during and after World War II, rising to the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He wa ...

, comprised VII Corps (Utah) and V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Arm ...

(Omaha). On the British side, Lieutenant-General Miles Dempsey

General Sir Miles Christopher Dempsey, (15 December 1896 – 5 June 1969) was a senior British Army officer who served in both world wars. During the Second World War he commanded the Second Army in northwest Europe. A highly professional car ...

commanded the Second Army, under which XXX Corps was assigned to Gold and I Corps to Juno and Sword. Land forces were under the command of Montgomery, and air command was assigned to Air Chief Marshal

Air chief marshal (Air Chf Mshl or ACM) is a high-ranking air officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many Commonwealth of Nations, countries that have historical British i ...

Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory

Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, (11 July 1892 – 14 November 1944) was a senior commander in the Royal Air Force. Leigh-Mallory served as a Royal Flying Corps pilot and squadron commander during the First World War. Remaining in th ...

. The First Canadian Army

The First Canadian Army () was a field army and a formation of the Canadian Army in World War II in which most Canadian elements serving in North-West Europe were assigned. It served on the Western Front from July 1944 until May 1945. It was Cana ...

included personnel and units from Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Other Allied nations participated.

Reconnaissance

The

The Allied Expeditionary Air Force

The Allied Expeditionary Air Force (AEAF), also known as the Allied Armies’ Expeditionary Air Force (AAEAF), was the expeditionary warfare component of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) which controlled the tactical air ...

flew over 3,200 photo-reconnaissance sorties from April 1944 until 6 June. Photos of the coastline were taken at extremely low altitude to show the invaders the terrain, obstacles on the beach, and defensive structures such as bunkers and gun emplacements. To conceal the location of the invasion, sorties were flown along all European coastline. Inland terrain, bridges, troop emplacements, and buildings were also photographed, in many cases from several angles. Members of Combined Operations Pilotage Parties

Combined Operations Headquarters was a department of the British War Office set up during Second World War to harass the Germans on the European continent by means of raids carried out by use of combined naval and army forces.

History

The comm ...

clandestinely prepared detailed harbour maps, including depth sounding

Depth sounding, often simply called sounding, is measuring the depth of a body of water. Data taken from soundings are used in bathymetry to make maps of the floor of a body of water, such as the seabed topography.

Soundings were traditional ...

s. An appeal for holiday pictures and postcards of Europe announced on the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

produced over ten million items, some of which proved useful. The French resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

provided details on Axis troop movements and on construction techniques used by the Germans for bunkers and other defensive installations.

Many German radio messages were encoded using the Enigma machine

The Enigma machine is a cipher device developed and used in the early- to mid-20th century to protect commercial, diplomatic, and military communication. It was employed extensively by Nazi Germany during World War II, in all branches of the W ...

and other enciphering techniques and the codes were changed frequently. A team of code breakers stationed at Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and Bletchley Park estate, estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire), that became the principal centre of Allies of World War II, Allied World War II cryptography, code-breaking during the S ...

worked to break codes as quickly as possible to provide advance information on German plans and troop movements. British military intelligence code-named this information Ultra

Ultra may refer to:

Science and technology

* Ultra (cryptography), the codename for cryptographic intelligence obtained from signal traffic in World War II

* Adobe Ultra, a vector-keying application

* Sun Ultra series, a brand of computer work ...

intelligence as it could only be provided to the most senior commanders. The Enigma code used by Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt

Karl Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt (12 December 1875 – 24 February 1953) was a German ''Generalfeldmarschall'' (Field Marshal) in the ''German Army (1935–1945), Heer'' (Army) of Nazi Germany and OB West, ''Oberbefehlshaber West'' (Commande ...

, ''Oberbefehlshaber'' West (Supreme Commander West; OB West

''Oberbefehlshaber West'' ( German: initials ''OB West'') (German: "Commander-in-Chief n theWest") was the overall commander of the '' Westheer'', the German armed forces on the Western Front during World War II. It was directly subordinate to t ...

), commander of the Western Front, was broken by the end of March. German intelligence changed the Enigma codes after the Allied landings but by 17 June the Allies were again consistently able to read them.

Technology

After the disastrous

After the disastrous Dieppe Raid

Operation Jubilee or the Dieppe Raid (19 August 1942) was a disastrous Allied amphibious attack on the German-occupied port of Dieppe in northern France, during the Second World War. Over 6,050 infantry, predominantly Canadian, supported by a ...

, the Allies developed new technologies for Overlord. To supplement the preliminary offshore bombardment and aerial assaults, some of the landing craft were equipped with artillery and anti-tank guns to provide close supporting fire. The Allies had decided not to immediately attack any of the heavily protected French ports and two artificial ports, called Mulberry harbour

The Mulberry harbours were two temporary portable harbours developed by the Admiralty (United Kingdom), British Admiralty and War Office during the Second World War to facilitate the rapid offloading of cargo onto beaches during the Allies of ...

s, were designed by COSSAC planners. Each assembly consisted of a floating outer breakwater

Breakwater may refer to:

* Breakwater (structure), a structure for protecting a beach or harbour

Places

* Breakwater, Victoria, a suburb of Geelong, Victoria, Australia

* Breakwater Island, Antarctica

* Breakwater Islands, Nunavut, Canada

* ...

, inner concrete caissons

Caisson (French for "box") may refer to:

* Caisson (engineering), a sealed underwater structure

* Caisson (vehicle), a two-wheeled cart for carrying ammunition, also used in certain state and military funerals

* Caisson (Asian architecture), a sp ...

(called Phoenix breakwaters

The Phoenix breakwaters were a set of reinforced concrete caissons built as part of the artificial Mulberry harbours that were assembled as part of the preparations for the Normandy landings during World War II. A total of 213 were built, with ...

) and several floating piers. The Mulberry harbours were supplemented by blockship

A blockship is a ship deliberately sunk to prevent a river, channel, or canal from being used as a waterway. It may either be sunk by a navy defending the waterway to prevent the ingress of attacking enemy forces, as in the case of at Portland ...

shelters (codenamed "Gooseberries"). With the expectation that fuel would be difficult or impossible to obtain on the continent, the Allies built a "Pipe-Line Under The Ocean" (PLUTO

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of Trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the Su ...

). Specially developed pipes in diameter were to be laid under the Channel from the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

to Cherbourg by D-Day plus 18. Technical problems and the delay in capturing Cherbourg meant the pipeline was not operational until 22 September. A second line was laid from Dungeness

Dungeness (, ) is a headland on the coast of Kent, England, formed largely of a shingle beach in the form of a cuspate foreland. It shelters a large area of low-lying land, Romney Marsh. Dungeness spans Dungeness Nuclear Power Station, the ham ...

to Boulogne in late October.

The British built specialised tanks, nicknamed Hobart's Funnies

Hobart's Funnies is the nickname given to a number of specialist armoured fighting vehicles derived from tanks operated during the Second World War by units of the 79th Armoured Division of the British Army or by specialists from the Royal En ...

, to deal with conditions expected during the Normandy campaign. Developed under the supervision of Major-General Percy Hobart

Major-General Sir Percy Cleghorn Stanley Hobart, (14 June 1885 – 19 February 1957), also known as "Hobo", was a British military engineer noted for his command of the 79th Armoured Division during the Second World War. He was responsible for ...

, these were modified M4 Sherman

The M4 Sherman, officially medium tank, M4, was the medium tank most widely used by the United States and Western Allies in World War II. The M4 Sherman proved to be reliable, relatively cheap to produce, and available in great numbers. I ...

and Churchill tank

The Tank, Infantry, Mk IV (A22) Churchill was a British infantry tank used in the Second World War, best known for its heavy armour, large longitudinal chassis with all-around tracks with multiple Bogie#Tracked vehicles, bogies, its ability to ...

s. Examples include the Sherman Crab tank (equipped with a mine flail), the Churchill Crocodile

The Churchill Crocodile was a British flame-throwing tank of late Second World War. It was a variant of the Tank, Infantry, Mk IV (A22) Churchill Mark VII, although the Churchill Mark IV was initially chosen to be the base vehicle.

The Croco ...

(a flame-throwing tank), and the Armoured Ramp Carrier

This is a list of specialist variants of the British Churchill tank.

Churchill Oke

A Churchill Mark II or Mark III with a flamethrower. Developed for the Dieppe Raid, amphibious raid on Dieppe in 1942, the Oke flamethrowing tank was named aft ...

, which other tanks could use as a bridge to scale sea-walls or to overcome other obstacles. In some areas, the beaches consisted of a soft clay that could not support the weight of tanks. The Bobbin

A bobbin or spool is a spindle or cylinder, with or without flanges, on which yarn, thread, wire, tape or film is wound. Bobbins are typically found in industrial textile machinery, as well as in sewing machines, fishing reels, tape measures ...

tank unrolled matting over the soft surface, leaving it behind as a route for ordinary tanks. The Assault Vehicle Royal Engineers (AVRE) was a Churchill tank modified for many combat engineering tasks, including laying bridges; it was armed with a demolition gun that could fire large charges into pillboxes. The Duplex-Drive tank (DD tank

DD or duplex drive tanks, nicknamed "Donald Duck tanks", were a type of amphibious vehicle, amphibious swimming tank developed by the British during the Second World War. The phrase is mostly used for the Duplex Drive variant of the M4 Sherman ...

), another design developed by Hobart's group, was a self-propelled amphibious tank kept afloat using a waterproof canvas screen inflated with compressed air. These tanks were easily swamped, and on D-Day, many sank before reaching the shore, especially at Omaha.

Deception

In the months leading up to the invasion, the Allies conductedOperation Bodyguard

Operation Bodyguard was the code name for a World War II military deception, deception strategy employed by the Allies of World War II, Allied states before the 1944 invasion of northwest Europe. Bodyguard set out an overall stratagem for mislea ...

, the overall strategy designed to mislead the Germans as to the date and location of the main Allied landings. Operation Fortitude

Operation Fortitude was a military deception operation by the Allied nations as part of Operation Bodyguard, an overall deception strategy during the buildup to the 1944 Normandy landings. Fortitude was divided into two subplans, North and So ...

included Fortitude North, a misinformation campaign using fake radio-traffic to lead the Germans into expecting an attack on Norway, and Fortitude South, a major deception designed to fool the Germans into believing that the landings would take place at Pas de Calais

The Strait of Dover or Dover Strait, historically known as the Dover Narrows, is the strait at the narrowest part of the English Channel, marking the boundary between the Channel and the North Sea, and separating Great Britain from continental ...

in July. A fictitious First U.S. Army Group was invented, supposedly located in Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

and Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

under the command of Lieutenant General George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (11 November 1885 – 21 December 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, then the Third Army in France and Germany after the Alli ...

. The Allies constructed dummy tanks, trucks, and landing craft, and positioned them near the coast. Several military units, including II Canadian Corps and 2nd Canadian Division

The 2nd Canadian Division (2 Cdn Div; ) is a formation of the Canadian Army in the province of Quebec, Canada. The present command was created 2013 when Land Force Quebec Area was re-designated. The main unit housed in this division is the Roy ...

, moved into the area to bolster the illusion that a large force was gathering there. As well as the broadcast of fake radio-traffic, genuine radio messages from 21st Army Group were first routed to Kent via landline and then broadcast, to give the Germans the impression that most of the Allied troops were stationed there. Patton remained stationed in England until 6 July, thus continuing to deceive the Germans into believing a second attack would take place at Calais. Military and civilian personnel alike were aware of the need for secrecy, and the invasion troops were as much as possible kept isolated, especially in the period immediately before the invasion. American general Henry J. F. Miller was sent back to the United States in disgrace after revealing the invasion date at a party.

The Germans thought they had an extensive network of spies operating in the UK, but in fact, all their agents had been captured, and some had become double agent

In the field of counterintelligence, a double agent is an employee of a secret intelligence service for one country, whose primary purpose is to spy on a target organization of another country, but who is now spying on their own country's organi ...

s working for the Allies as part of the Double-Cross System

The Double-Cross System or XX System was a World War II counter-espionage and deception operation of the British Security Service ( MI5). Nazi agents in Britain – real and false – were captured, turned themselves in or simply announced themse ...

. The double agent Juan Pujol García

Juan Pujol García (; 14 February 1912 – 10 October 1988), also known as Joan Pujol i García (), was a Spanish spy who acted as a double agent loyal to Great Britain against Nazi Germany during World War II, when he relocated to Britain t ...

, a Spanish opponent of the Nazis known by the code name "Garbo", developed over the two years leading up to D-Day a fake network of informants that the Germans believed were collecting intelligence on their behalf. In the months preceding D-Day, Pujol sent hundreds of messages to his superiors in Madrid, messages specially prepared by the British intelligence service to convince the Germans that the attack would come in July at Calais.

Many of the German radar stations on the French coast were destroyed by the RAF in preparation for the landings. On the night before the invasion, in Operation Taxable

Operations Taxable, Glimmer and Big Drum were tactical military deceptions conducted on 6 June 1944 in support of the Allied landings in Normandy. The operations formed the naval component of Operation Bodyguard, a wider series of tactical an ...

, 617 Squadron (the famous "Dambusters") dropped strips of "window", metal foil

A foil is a very thin sheet of metal, typically made by hammering or rolling. Foils are most easily made with malleable metal, such as aluminium, copper, tin, and gold. Foils usually bend under their own weight and can be torn easily. For example ...

that German radar operators interpreted as a naval convoy approaching Cap d'Antifer (about from the actual D-Day landings). The illusion was bolstered by a group of small vessels towing barrage balloon

A barrage balloon is a type of airborne barrage, a large uncrewed tethered balloon used to defend ground targets against aircraft attack, by raising aloft steel cables which pose a severe risk of collision with hostile aircraft, making the atta ...

s. No. 218 Squadron RAF

No. 218 Squadron RAF was a squadron of the Royal Air Force. It was also known as No 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron after the Governor of the Gold Coast (modern Ghana) and people of the Gold Coast officially adopted the squadron.

History

World War ...

also dropped "window" near Boulogne-sur-Mer

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

in Operation Glimmer

Operations Taxable, Glimmer and Big Drum were tactical military deceptions conducted on 6 June 1944 in support of the Allied landings in Normandy. The operations formed the naval component of Operation Bodyguard, a wider series of tactical an ...

. On the same night, a small group of Special Air Service

The Special Air Service (SAS) is a special forces unit of the British Army. It was founded as a regiment in 1941 by David Stirling, and in 1950 it was reconstituted as a corps. The unit specialises in a number of roles including counter-terr ...

(SAS) operators deployed dummy paratroopers over Le Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

and Isigny. These dummies led the Germans to believe an additional airborne assault had occurred.

Rehearsals and security

Training exercises for the Overlord landings took place as early as July 1943. As the nearby beach resembled the planned Normandy landing-site, the town of Slapton in Devon, was evacuated in December 1943, and taken over by the armed forces as a site for training exercises that included the use of landing craft and the management of beach obstacles. A

Training exercises for the Overlord landings took place as early as July 1943. As the nearby beach resembled the planned Normandy landing-site, the town of Slapton in Devon, was evacuated in December 1943, and taken over by the armed forces as a site for training exercises that included the use of landing craft and the management of beach obstacles. A friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy or hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while ...

incident there on 27 April 1944 resulted in as many as 450 deaths. The following day, an additional estimated 749 American soldiers and sailors died when German torpedo-boats surprised members of Assault Force "U" conducting Exercise Tiger

Exercise Tiger, or Operation Tiger was one of a series of large-scale rehearsals for the D-Day invasion of Normandy. Held in April 1944 on Slapton Sands in Devon, it proved fraught with difficulties. Coordination and communication problems r ...

. Exercises with landing craft and live ammunition also took place at the Combined Training Centre in Inveraray

Inveraray ( or ; meaning "mouth of the Aray") is a town in Argyll and Bute, Scotland. Located on the western shore of Loch Fyne, near its head, Inveraray is a former royal burgh and known affectionately as "The Capital of Argyll." It is the ...

in Scotland. Naval exercises took place in Northern Ireland, and medical teams in London and elsewhere rehearsed how they would handle the expected waves of casualties. Paratroopers conducted exercises, including a huge demonstration drop on 23 March 1944 observed by Churchill, Eisenhower, and other top officials.

Allied planners considered tactical surprise to be a necessary element of the plan for the landings. Information on the exact date and location of the landings was provided only to the topmost levels of the armed forces. Men were sealed into their marshalling areas at the end of May, with no further communication with the outside world. Troops were briefed using maps that were correct in every detail except for the place names, and most were not told their actual destination until they were already at sea. A news blackout in Britain increased the effectiveness of the deception operations. Travel to and from the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

was banned, and movement within several kilometres of the coast of England restricted.

Weather forecasting

The invasion planners specified a set of conditions regarding the timing of the invasion, deeming only a few days in each month suitable. A full moon was desirable, as it would provide illumination for aircraft pilots and have the highest tides. The Allies wanted to schedule the landings for shortly before dawn, midway between low and high tide, with the tide coming in. This would improve the visibility of obstacles the enemy had placed on the beach while minimising the amount of time the men had to spend exposed in the open. Specific criteria were also set for wind speed, visibility, and cloud cover. Eisenhower had tentatively selected 5 June as the date for the assault; however, on 4 June, conditions were clearly unsuitable for a landing, as high winds and heavy seas made it impossible to launch landing craft, and low clouds would prevent aircraft from finding their targets.

By the evening of 4 June, the Allied meteorological team, headed by Group Captain

The invasion planners specified a set of conditions regarding the timing of the invasion, deeming only a few days in each month suitable. A full moon was desirable, as it would provide illumination for aircraft pilots and have the highest tides. The Allies wanted to schedule the landings for shortly before dawn, midway between low and high tide, with the tide coming in. This would improve the visibility of obstacles the enemy had placed on the beach while minimising the amount of time the men had to spend exposed in the open. Specific criteria were also set for wind speed, visibility, and cloud cover. Eisenhower had tentatively selected 5 June as the date for the assault; however, on 4 June, conditions were clearly unsuitable for a landing, as high winds and heavy seas made it impossible to launch landing craft, and low clouds would prevent aircraft from finding their targets.

By the evening of 4 June, the Allied meteorological team, headed by Group Captain James Stagg

Group Captain James Martin Stagg, (30 June 1900 – 23 June 1975) was a British Met Office meteorologist attached to the Royal Air Force during the Second World War who notably persuaded General Dwight D. Eisenhower to change the date of the A ...

of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

, predicted that the weather would improve sufficiently so that the invasion could go ahead on 6 June. He met Eisenhower and other senior commanders at their headquarters at Southwick House

Southwick House is a Grade II listed 19th-century manor house of the Southwick Estate in Hampshire, England, about north of Portsmouth. It is home to the Defence School of Policing and Guarding and related military police capabilities.

Histor ...

in Hampshire to discuss the situation. General Montgomery and Major-General Walter Bedell Smith

General (United States), General Walter Bedell "Beetle" Smith (5 October 1895 – 9 August 1961) was a senior officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army who served as General Dwight D. Eisenhower's chief of staff at Allied Forc ...

, Eisenhower's chief of staff, were eager to launch the invasion. Admiral Bertram Ramsay was prepared to commit his ships, while Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory expressed concern that the conditions would be unfavourable for Allied aircraft. After much discussion, Eisenhower decided that the invasion should go ahead. Allied control of the Atlantic meant that German meteorologists did not have access to as much information as the Allies on incoming weather patterns. As the Luftwaffe meteorological centre in Paris predicted two weeks of stormy weather, many Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

commanders left their posts to attend war games in Rennes

Rennes (; ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Resnn''; ) is a city in the east of Brittany in Northwestern France at the confluence of the rivers Ille and Vilaine. Rennes is the prefecture of the Brittany (administrative region), Brittany Regions of F ...

, and men in many units were given leave. Marshal Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel (; 15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944), popularly known as The Desert Fox (, ), was a German '' Generalfeldmarschall'' (field marshal) during World War II. He served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of ...

returned to Germany for his wife's birthday and to meet Hitler to try to get more tanks.

Had Eisenhower postponed the invasion again, the next available period with the right combination of tides (but without the desirable full moon) was two weeks later, from 18 to 20 June. As it happened, during this period the invaders would have encountered a major storm lasting four days, between 19 and 22 June, that would have made the initial landings impossible.

German preparations and defences

Nazi Germany had at its disposal 50 divisions in France and the Low Countries, with another 18 stationed in Denmark and Norway. Fifteen divisions were in the process of formation in Germany, but there was no strategic reserve. The Calais region was defended by the 15th Army under (Colonel General)Hans von Salmuth

Hans Eberhard Kurt Freiherr von Salmuth (11 November 1888 – 1 January 1962) was a German general of the ''Wehrmacht'' during World War II. Salmuth commanded several armies on the Eastern Front, and the Fifteenth Army in France during the D- ...

, and Normandy by the 7th Army commanded by ''Generaloberst'' Friedrich Dollmann