Alexey Romanov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia (russian: Алексе́й Алекса́ндрович; in St. Petersburg – 14 November 1908 in Paris) was the fifth child and the fourth son of

Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia (russian: Алексе́й Алекса́ндрович; in St. Petersburg – 14 November 1908 in Paris) was the fifth child and the fourth son of

On 18 September 1866 Alexei was promoted to

On 18 September 1866 Alexei was promoted to

In 1869/1870, Alexei had an affair with

In 1869/1870, Alexei had an affair with

Upset by his son's affair, Alexander II even refused to grant Alexandra Zhukovskaya a title, which would have officially recognized the Grand Duke's paternity, even if illegitimate. Other European courts also refused to grant her a title. As a solution of last resort, on 25 March 1875 Alexandra was able to secure the title of Baroness Seggiano from the

On 22 November 1871, Alexei left for Washington, D.C. by special train, placed at his disposal by the

On 22 November 1871, Alexei left for Washington, D.C. by special train, placed at his disposal by the

From there the train continued to

From there the train continued to

"The Grand Duke Alexis"

''McCook Gazette'', Monday, 31 December 2007 ] General Custer became one of the Duke's best friends. He accompanied him and his entourage through Kansas, to St. Louis, New Orleans, and finally to Florida. They continued to correspond with one another up until Custer's death. In the United States, the hunt is remembered as "The Great Royal Buffalo Hunt". Starting from the year 2000,

Alexander II of Russia

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Fin ...

and his first wife Maria Alexandrovna (Marie of Hesse)

Maria Alexandrovna ( rus, Мария Александровна), born Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine (8 August 1824 – 3 June 1880), was Empress of Russia as the first wife and political adviser of Emperor Alexander II. She was one of the ...

. Chosen for a naval career, Alexei Alexandrovich started his military training at the age of seven. By the age of 20 he had been appointed lieutenant of the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from ...

and had visited all Russia's European military ports. In 1871, he was sent as a goodwill ambassador

Goodwill ambassador is a post-nominal honorific title, a professional occupation and/or authoritative designation that is assigned to a person who advocates for a specific cause or global issue on the basis of their notability such as a publi ...

to the United States and Japan.

In 1883 he was appointed general-admiral. He had a significant contribution in the equipment of the Russian navy with new ships and in modernizing the naval ports. However, after the Russian defeat in the Battle of Tsushima

The Battle of Tsushima (Japanese:対馬沖海戦, Tsushimaoki''-Kaisen'', russian: Цусимское сражение, ''Tsusimskoye srazheniye''), also known as the Battle of Tsushima Strait and the Naval Battle of Sea of Japan (Japanese: 日 ...

in 1905, and viewed as an incompetent and corrupt dilettante, he was relieved of his command. He died in Paris in 1908.

Early life

The Grand Duke Alexei AlexandrovichRomanov

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

of Russia was born in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

on 14 January 1850 (4 January O.S.). He was the son of emperor Alexander II and empress Maria Alexandrovna. He was a younger brother of Grand Duchess Alexandra Alexandrovna, Tsarevich Nikolay Alexandrovich, Alexander III of Russia

Alexander III ( rus, Алекса́ндр III Алекса́ндрович, r=Aleksandr III Aleksandrovich; 10 March 18451 November 1894) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland from 13 March 1881 until his death in 18 ...

, Grand Duke Vladmir Alexandrovich. He was an older brother of Duchess Maria of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich

Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia (''Сергей Александрович''; 11 May 1857 – 17 February 1905) was the fifth son and seventh child of Emperor Alexander II of Russia. He was an influential figure during the reigns of hi ...

and Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich

Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia (russian: Павел Александрович; 3 October 1860 – 28 January 1919) was the sixth son and youngest child of Emperor Alexander II of Russia by his first wife, Empress Maria Alexandrov ...

.

Alexei was chosen for a naval career since his childhood. At the age of 7 he received the rank of midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Af ...

. The next year Konstantin Nikolayevich Posyet was appointed as his tutor. While the winters were dedicated to theoretical studies, during the summers he trained on Russian warships of the Baltic fleet stationed in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

harbour

A harbor (American English), harbour (British English; see spelling differences), or haven is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be docked. The term ''harbor'' is often used interchangeably with ''port'', which is ...

. Training exposed him to various sailing ships:

* in 1860 the yacht ''Shtandart'' on a cruise from Petergof

Petergof (russian: Петерго́ф), known as Petrodvorets () from 1944 to 1997, is a municipal town in Petrodvortsovy District of the federal city of St. Petersburg, located on the southern shore of the Gulf of Finland.

The town hos ...

to Livada

* in 1861–1863 the yacht ''Zabava'' under the flag of Counter-Admiral Posyet in the Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland ( fi, Suomenlahti; et, Soome laht; rus, Фи́нский зали́в, r=Finskiy zaliv, p=ˈfʲinskʲɪj zɐˈlʲif; sv, Finska viken) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and E ...

and Gulf of Bothnia,

* in 1864 the frigate ''Svetlana'' in the Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland ( fi, Suomenlahti; et, Soome laht; rus, Фи́нский зали́в, r=Finskiy zaliv, p=ˈfʲinskʲɪj zɐˈlʲif; sv, Finska viken) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and E ...

and the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and fr ...

* in 1866 the frigate ''Oslyabya'' during an extensive training cruise to the Azore Islands

)

, motto=

( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem=( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

.Ю.Л.Коршунов

On 18 September 1866 Alexei was promoted to

On 18 September 1866 Alexei was promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

. He continued his navy career serving as officer aboard the frigate ''Alexander Nevsky'' on a cruise in across the Mediterranean to Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Sar ...

, where he attended the wedding of his cousin Olga Konstantinovna.

In 1868 he went on a trip to southern Russia traveling by train from Saint Petersburg to Nikolayevsk, continuing by ship down the Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchm ...

to Astrakhan

Astrakhan ( rus, Астрахань, p=ˈastrəxənʲ) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in Southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of ...

. He then boarded a military ship for a cruise on the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad s ...

to Baku, etrovsk (now Makhachkala) and then to Iran">Makhachkala.html" ;"title="etrovsk (now Makhachkala">etrovsk (now Makhachkala) and then to Iran. He then crossed the Caucasus and reached Poti where the ''Alexander Nevsky'' was moored. From there he sailed to Constantinople, Athens and the Azore Islands

)

, motto=

( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem=( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

On the return voyage, the frigate was wrecked off the coast of Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

during a storm on the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. Though the ship was lost, all but five crew members were unhurt and safely reached shore.

In January 1870 Alexei Alexandrovich reached the age of majority

The age of majority is the threshold of legal adulthood as recognized or declared in law. It is the moment when minors cease to be considered such and assume legal control over their persons, actions, and decisions, thus terminating the contro ...

according to Russian legislation. The event was marked by taking two oaths : the military one and the oath of allegiance of the Grand Dukes of the Russian Imperial House. In June 1870 Alexei started the last part of his training. This included inland navigation on a cutter

Cutter may refer to:

Tools

* Bolt cutter

* Box cutter, aka Stanley knife, a form of utility knife

* Cigar cutter

* Cookie cutter

* Glass cutter

* Meat cutter

* Milling cutter

* Paper cutter

* Side cutter

* Cutter, a type of hydraulic rescue to ...

with a steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

, on the route from Saint Petersburg to Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ; rus, Арха́нгельск, p=ɐrˈxanɡʲɪlʲsk), also known in English as Archangel and Archangelsk, is a city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina near i ...

through the Mariinsk Canal system

Mariinsk (russian: link=no, Мариинск) is a town in Kemerovo Oblast, Russia, where the Trans-Siberian Railway crosses the Kiya River ( Ob's basin), northeast of Kemerovo, the administrative center of the oblast. Population: 39,700 (197 ...

and the Northern Dvina

The Northern Dvina (russian: Се́верная Двина́, ; kv, Вы́нва / Výnva) is a river in northern Russia flowing through the Vologda Oblast and Arkhangelsk Oblast into the Dvina Bay of the White Sea. Along with the Pechora Riv ...

. After visiting the schools and industrial facilities of Arkhangelsk, he started his navigation training in arctic conditions, aboard the corvette ''Varyag''. This cruise took him to the Solovetsky Islands

The Solovetsky Islands (russian: Солове́цкие острова́), or Solovki (), are an archipelago located in the Onega Bay of the White Sea, Russia. As an administrative division, the islands are incorporated as Solovetsky District of ...

, continuing through the White Sea

The White Sea (russian: Белое море, ''Béloye móre''; Karelian and fi, Vienanmeri, lit. Dvina Sea; yrk, Сэрако ямʼ, ''Serako yam'') is a southern inlet of the Barents Sea located on the northwest coast of Russia. It is s ...

and Barents Sea

The Barents Sea ( , also ; no, Barentshavet, ; russian: Баренцево море, Barentsevo More) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia and divided between Norwegian and Russian ter ...

to Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; rus, Но́вая Земля́, p=ˈnovəjə zʲɪmˈlʲa, ) is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island ...

. The route continued to Kola Bay

Kola Bay (russian: Кольский залив) or Murmansk Fjord is a 57-km-long fjord of the Barents Sea that cuts into the northern part of the Kola Peninsula. It is up to 7 km wide and has a depth of 200 to 300 metres. The Tuloma, Rosta ...

and the city of Murmansk

Murmansk ( Russian: ''Мурманск'' lit. " Norwegian coast"; Finnish: ''Murmansk'', sometimes ''Muurmanski'', previously ''Muurmanni''; Norwegian: ''Norskekysten;'' Northern Sámi: ''Murmánska;'' Kildin Sámi: ''Мурман ланнҍ ...

, the ports of northern Norway and Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

. He returned to Cronstadt at the end of September.

Love affair with Alexandra Zhukovskaya

In 1869/1870, Alexei had an affair with

In 1869/1870, Alexei had an affair with Alexandra Zhukovskaya

Alexandra Vasilievna Zhukovskaya (11 November 1842 in Düsseldorf – 26 August 1899 in Wendischbora, Germany), was a Russian noble and lady in waiting.

Life

She was the daughter of Vasily Andreyevich Zhukovsky and Elizabeth von Reutern. Her ...

, daughter of poet Vasily Andreyevich Zhukovsky

Vasily Andreyevich Zhukovsky (russian: Василий Андреевич Жуковский, Vasiliy Andreyevich Zhukovskiy; – ) was the foremost Russian poet of the 1810s and a leading figure in Russian literature in the first half of the 19t ...

, who was eight years older than he was. They had a son, Alexei

Alexey, Alexei, Alexie, Aleksei, or Aleksey (russian: Алексе́й ; bg, Алексей ) is a Russian and Bulgarian male first name deriving from the Greek ''Aléxios'' (), meaning "Defender", and thus of the same origin as the Latin ...

, born on 26 November 1871. Tsar Alexander II was strongly opposed to this relationship.

Some historians claim that they were morganatically married and that the marriage was annulled by the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

, because, according to the "Fundamental Laws of the Imperial House", this marriage was illegal. However, articles 183 and 188, which prohibited marriages without the consent of the emperor, were included in the Fundamental Laws only by the 1887 revision under Tsar Alexander III. The rules valid in 1870 did not prohibit morganatic marriage

Morganatic marriage, sometimes called a left-handed marriage, is a marriage between people of unequal social rank, which in the context of royalty or other inherited title prevents the principal's position or privileges being passed to the spous ...

s, but simply excluded their offspring from the succession to the throne. There is no evidence either to the marriage or to the divorce. There is also no evidence that Alexei even requested the permission to marry. As Alexandra Zhukovskaya was not an aristocrat and, besides, the daughter of an illegitimate son of a Russian landowner and a Turkish slave, such a marriage would have been unthinkable.Stanislaw Dumin – Les Romanov et la république de Saint-MarinUpset by his son's affair, Alexander II even refused to grant Alexandra Zhukovskaya a title, which would have officially recognized the Grand Duke's paternity, even if illegitimate. Other European courts also refused to grant her a title. As a solution of last resort, on 25 March 1875 Alexandra was able to secure the title of Baroness Seggiano from the

Republic of San Marino

San Marino (, ), officially the Republic of San Marino ( it, Repubblica di San Marino; ), also known as the Most Serene Republic of San Marino ( it, Serenissima Repubblica di San Marino, links=no), is the fifth-smallest country in the world an ...

, with the right to transmit the title to her son and his firstborn male descendants. It was only in 1883, that Alexander III, Alexei's elder brother, granted the Baron Seggiano the title of Count Belevsky, and in 1893 approved his coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in it ...

.

Overseas tours

United States

Voyage

After the official visit toSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

of an American squadron under the command of Admiral David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. F ...

in 1867, a high level visit of the Russian Navy was envisaged by the Russian Government. After lengthy negotiations, it was decided that the Russian delegation would be headed by the Grand Duke. The official announcement of the visit was made on 29 June 1871 by Nikolay Karlovich Krabbe

Nikolay Karlovich Krabbe (russian: link=no, Николай Карлович Краббе) (September 19, 1814 – January 3, 1876) served as an admiral of the Russian Imperial Navy and as Minister of the Navy from 1860 to 1874.

After graduating ...

, Minister of the Imperial Russian Navy.

The Russian squadron, under the command of Admiral Konstantin Nikolayevich Posyet on board the frigate ''Bogatyr'', included the frigates ''Svetlana'' and ''General-Admiral'', the corvette ''Ignatiev'' and the gunboat ''Abrek''. Alexei was serving as lieutenant aboard the ''Svetlana''. Before reaching the United States, the Russian squadron was to be met by the frigate ''Vsadnik'' of the Russian Pacific Fleet. Though all ships were equipped with steam-engines, the squadron made the passage to America mainly under sail, so as to avoid making port on the route for coal supplies. In addition to Alexei's personal staff, the crew included 200 officers and over 3000 sailors. The squadron set sail out of Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for " crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city ...

on 20 August 1871.

The squadron first stopped in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

, where he paid a visit to King Christian IX of Denmark

Christian IX (8 April 181829 January 1906) was List of Danish monarchs, King of Denmark from 1863 until his death in 1906. From 1863 to 1864, he was concurrently List of dukes of Schleswig, Duke of Schleswig, List of dukes of Holstein, Holstein ...

. In the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or (Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kan ...

the Russians were met by a squadron of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

and escorted to Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymout ...

, where Alexei was met by the Duke of Edinburgh Alfred of Saxe-Coburg. A visit to Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle () is a large estate house in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and a residence of the British royal family. It is near the village of Crathie, west of Ballater and west of Aberdeen.

The estate and its original castle were boug ...

had been scheduled, but had to be canceled because the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

was very sick and Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

extremely concerned.

The Russian squadron set sail from Plymouth on 26 September, and, en route to New York, stopped for a few days in Funchal

Funchal () is the largest city, the municipal seat and the capital of Portugal's Autonomous Region of Madeira, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean. The city has a population of 105,795, making it the sixth largest city in Portugal. Because of its high ...

, (Madeira Islands

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

), leaving on 9 October.

The Russian squadron was met by an American squadron under the command of Vice-Admiral Stephen Clegg Rowan

Stephen Clegg Rowan (December 25. 1808 – March 31, 1890) was a Vice admiral (United States), vice admiral in the United States Navy, who served during the Mexican–American War and the American Civil War.

Early life and career

Born in Dub ...

, Port Admiral of New York, hoisting his flag on the frigate . Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee

Samuel Phillips Lee (February 13, 1812 – June 5, 1897) was an officer of the United States Navy. In the American Civil War, he took part in the New Orleans campaign, before commanding the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, covering the c ...

, commander of the North Atlantic Squadron

The North Atlantic Squadron was a section of the United States Navy operating in the North Atlantic. It was renamed as the North Atlantic Fleet in 1902. In 1905 the European and South Atlantic squadrons were abolished and absorbed into the Nort ...

attended on his own flagship, the USS ''Severn''. The other ships of the squadron were the and the , attended by several tugs.

A welcoming committee had been formed in New York, chaired by William Henry Aspinwall

William Henry Aspinwall (December 16, 1807 – January 18, 1875) was a prominent American businessman who was a partner in the merchant firm of Howland & Aspinwall and was a co-founder of both the Pacific Mail Steamship Company and Panama Ca ...

. Among the members of the committee were Moses H. Grinnell

Moses Hicks Grinnell (March 3, 1803 – November 24, 1877) was a United States Congressman representing New York, and a Commissioner of New York City's Central Park.

Early life

Grinnell was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, on March 3, ...

, General Irwin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command ...

, Theodore Roosevelt, Sr.

Theodore Roosevelt Sr. (September 22, 1831 – February 9, 1878) was an American businessman and philanthropist from the Roosevelt family. Roosevelt was also the father of President Theodore Roosevelt and the paternal grandfather of First Lady E ...

Rear-Admiral S. W. Godon

S is the nineteenth letter of the English alphabet.

S may also refer to:

History

* an Anglo-Saxon charter's number in Peter Sawyer's, catalogue Language and linguistics

* Long s (ſ), a form of the lower-case letter s formerly used where "s ...

, John Taylor Johnston

John Taylor Johnston (April 8, 1820 – March 24, 1893) was an American businessman and patron of the arts. He served as President of the Central Railroad of New Jersey and was one of the founders of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Early life

Joh ...

, Albert Bierstadt

Albert Bierstadt (January 7, 1830 – February 18, 1902) was a German-American painter best known for his lavish, sweeping landscapes of the American West. He joined several journeys of the Westward Expansion to paint the scenes. He was not ...

, Lloyd Aspinwall

John Lloyd Aspinwall (December 12, 1834 – September 4, 1886) was an American lawyer and soldier who served in the U.S. Civil War, achieving the rank of brigadier general in the U.S. National Guard.

Early life

Lloyd, as he was commonly know ...

and others.

After a short delay due to the weather, the Russian squadron anchored in New York Harbor on 21 November 1871, where the Grand Duke was greeted by general John Adams Dix

John Adams Dix (July 24, 1798 – April 21, 1879) was an American politician and military officer who was Secretary of the Treasury, Governor of New York and Union major general during the Civil War. He was notable for arresting the pro-South ...

. A military parade took place in the city. Alexei then attended a thanksgiving service at the Russian chapel

A chapel is a Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. Firstly, smaller spaces inside a church that have their own altar are often called chapels; the Lady chapel is a common typ ...

.

Reception by President Grant

On 22 November 1871, Alexei left for Washington, D.C. by special train, placed at his disposal by the

On 22 November 1871, Alexei left for Washington, D.C. by special train, placed at his disposal by the New Jersey Railroad and Transportation Company

The United New Jersey Railroad and Canal Company (UNJ&CC) was a railroad company which began as the important Camden & Amboy Railroad (C&A), whose 1830 lineage began as one of the eight or ten earliest permanent North AmericanList of Earliest Am ...

. The train had three cars: the "Commissariat" having all the modern improvements of a hotel, comprising store-rooms and pantry, the "Ruby", dining room car to accommodate 28 persons, with kitchen, ice boxes, and a sort of wine cellar, and the “Kearsarge,” used as sitting, sleeping and reading room.

On 23 November, he was received by president Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

. The president's wife, Julia Grant

Julia Boggs Grant ( née Dent; January 26, 1826 – December 14, 1902) was the first lady of the United States and wife of President Ulysses S. Grant. As first lady, she became a national figure in her own right. Her memoirs, ''The Personal Me ...

, and his daughter, Nellie Grant

Ellen Wrenshall "Nellie" Grant (July 4, 1855 – August 30, 1922) was the third child and only daughter of U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant and First Lady Julia Grant. At the age of 16, Nellie was sent abroad to England by President Grant, and ...

, also attended. Most of the members of the cabinet were present at the meeting: Hamilton Fish

Hamilton Fish (August 3, 1808September 7, 1893) was an American politician who served as the List of Governors of New York, 16th Governor of New York from 1849 to 1850, a United States Senate, United States Senator from New York (state), New Y ...

(United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's ...

), Columbus Delano

Columbus Delano (June 4, 1809 – October 23, 1896) was a lawyer, rancher, banker, statesman, and a member of the prominent Delano family. Forced to live on his own at an early age, Delano struggled to become a self-made man. Delano was electe ...

(United States Secretary of the Interior

The United States secretary of the interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior. The secretary and the Department of the Interior are responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land along with natura ...

) with his wife, Amos Tappan Akerman

Amos Tappan Akerman (February 23, 1821 – December 21, 1880) was an American politician who served as United States Attorney General under President Ulysses S. Grant from 1870 to 1871. A native of New Hampshire, Akerman graduated from Dartmouth ...

(United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

) with his wife, George S. Boutwell

George Sewall Boutwell (January 28, 1818 – February 27, 1905) was an American politician, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served as Secretary of the Treasury under U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant, the 20th Governor of Massachus ...

(United States Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal ...

), George Maxwell Robeson

George Maxwell Robeson (March 16, 1829 – September 27, 1897) was an American politician and lawyer from New Jersey. A brigadier general in the New Jersey Militia during the American Civil War, he served as Secretary of the Navy, appointed by Pr ...

(United States Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

), General Frederick Tracy Dent

Frederick Tracy Dent (December 17, 1820 – December 23, 1892) was an American general.

Early life

Dent was born on December 17, 1820 in White Haven, St. Louis County, Missouri. He was the son of Frederick Fayette Dent (1787–1873) and Ellen ...

(the president's brother-in-law and military secretary), John Creswell

John Andrew Jackson Creswell (November 18, 1828December 23, 1891) was an American politician and abolitionist from Maryland, who served as United States Representative, United States Senator, and as Postmaster General of the United States a ...

(Postmaster General of the United States

The United States Postmaster General (PMG) is the chief executive officer of the United States Postal Service (USPS). The PMG is responsible for managing and directing the day-to-day operations of the agency.

The PMG is selected and appointed by ...

), as well as generals Horace Porter

Horace Porter (April 15, 1837May 29, 1921) was an American soldier and diplomat who served as a lieutenant colonel, ordnance officer and staff officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War, personal secretary to General and President ...

and Orville E. Babcock

Orville Elias Babcock (December 25, 1835 – June 2, 1884) was an American engineer and general in the Union Army during the Civil War. An aide to General Ulysses S. Grant during and after the war, he was President Grant's military private secret ...

.

The visit to Washington was overshadowed by President Grant's discontent caused by the Russian government's refusal to recall Konstantin Katacazi, minister plenipotentiary of Russia to the United States. The entire visit in Washington lasted only one day. No formal entertainment was given in Washington to the Grand Duke, though for all other visits of members of royal families to the White House, formal dinners had been organized. Such dinners had taken place when President John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected v ...

received François d'Orléans, prince de Joinville

François () is a French masculine given name and surname, equivalent to the English name Francis.

People with the given name

* Francis I of France, King of France (), known as "the Father and Restorer of Letters"

* Francis II of France, King ...

, when Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

received Prince Napoleon Joseph Bonaparte and even when Ulysses Grant received Kamehameha V

Kamehameha V (Lota Kapuāiwa Kalanimakua Aliʻiōlani Kalanikupuapaʻīkalaninui; December 11, 1830 – December 11, 1872), reigned as the fifth monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi from 1863 to 1872. His motto was "Onipaʻa": immovable, firm, st ...

, king of the Sandwich Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Ku ...

. The evening of the visit to the White House, Alexei and his suite dined at the minister Katakazi's residence, the only American official attending being general Porter. At his departure Alexei was asked if he intended to return to Washington. Though he expressed his interest to return during a session of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, the uneasy diplomatic relations due to Minister Katakazi prevented this from happening. There had also been expectations that a military alliance treaty between the United States and Russia would be signed during the meeting; however this was not the case.

The next day, Alexei left by train for Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

where he visited the Naval Academy

A naval academy provides education for prospective naval officers.

See also

* Military academy

A military academy or service academy is an educational institution which prepares candidates for service in the officer corps. It normally pro ...

, thereafter returning to New York.

East Coast

In New York, he visited theBrooklyn Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York (state), New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a ...

, Fort Wadsworth

Fort Wadsworth is a former United States military installation on Staten Island in New York City, situated on The Narrows which divide New York Bay into Upper and Lower halves, a natural point for defense of the Upper Bay and Manhattan beyond. ...

and the fortifications on Governors Island

Governors Island is a island in New York Harbor, within the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is located approximately south of Manhattan Island, and is separated from Brooklyn to the east by the Buttermilk Channel. The National Park ...

. He also reviewed the Fire Department at Tompkins Square

Tompkins Square Park is a public park in the Alphabet City portion of East Village, Manhattan, New York City. The square-shaped park, bounded on the north by East 10th Street, on the east by Avenue B, on the south by East 7th Street, and o ...

. A highlight was the trip by steamer on the Hudson for the visit of the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

, West Point.

Several balls were organized in his honor, the most important being the grand balls at the Navy Yard and at the Academy of Music. Alexei attended opera performances of ''Faust'' and ''Mignon

''Mignon'' is an 1866 ''opéra comique'' (or opera in its second version) in three acts by Ambroise Thomas. The original French libretto was by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, based on Goethe's 1795-96 novel '' Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre''. ...

'' at the Academy of Music. He also went on a shopping spree, stopping at the A.T. Stewart

Alexander Turney Stewart (October 12, 1803 – April 10, 1876) was an American entrepreneur who moved to New York and made his multimillion-dollar fortune in the most extensive and lucrative dry goods store in the world.

Stewart was born in L ...

and Tiffany

Tiffany may refer to:

People

* Tiffany (given name), list of people with this name

* Tiffany (surname), list of people with this surname

Known mononymously as "Tiffany":

* Tiffany Darwish, (born 1971), an American singer, songwriter, actress kn ...

stores where he bought some jewellery and bronze statues.

On 2 December 1871, a ceremony took place at the National Academy of Design

The National Academy of Design is an honorary association of American artists, founded in New York City in 1825 by Samuel Morse, Asher Durand, Thomas Cole, Martin E. Thompson, Charles Cushing Wright, Ithiel Town, and others "to promote the f ...

, where the Grand Duke was received by Samuel F. B. Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

, William Stoddard

William Osborn Stoddard (1835–1925) was an American journalist, inventor, and author of memoirs, novels, poetry, and children's books. He was known for serving in the White House as a private secretary to Abraham Lincoln.

Biography

Stoddard ...

, William Page, Albert Bierstadt

Albert Bierstadt (January 7, 1830 – February 18, 1902) was a German-American painter best known for his lavish, sweeping landscapes of the American West. He joined several journeys of the Westward Expansion to paint the scenes. He was not ...

and several other artists. The painting ''Farragut in the shrouds of the Hartfort at the battle of Mobile Bay'' by William Page was handed over as a gift of the citizens of New York for Tsar Alexander II. General John Adams Dix

John Adams Dix (July 24, 1798 – April 21, 1879) was an American politician and military officer who was Secretary of the Treasury, Governor of New York and Union major general during the Civil War. He was notable for arresting the pro-South ...

presented the picture and the accompanying scroll, with a brief address in which he expressed the hope that it would further cement the union that existed between the United States and Russia. The painting was placed on board the Russian flagship for transportation to Russia.

On 3 December 1871, Alexei left for Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

where he was received by general George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. He ...

and Admiral Turner. He visited Girard College

Girard College is an independent college preparatory five-day boarding school located on a 43-acre campus in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The school was founded and permanently endowed from the shipping and banking fortune of Stephen Girard upon hi ...

, Baird Locomotive Works and the Navy Yard. He was particularly interested in the Methodist Fair at the Horticultural Hall, where the ladies presented him with an Afghan Hound

The Afghan Hound is a hound that is distinguished by its thick, fine, silky coat and its tail with a ring curl at the end. The breed is selectively bred for its unique features in the cold mountains of Afghanistan. Its local name is ( ps, تاژ ...

.

On 6 December 1871, Alexei visited the Smith & Wesson

Smith & Wesson Brands, Inc. (S&W) is an American firearm manufacturer headquartered in Springfield, Massachusetts, United States.

Smith & Wesson was founded by Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson as the "Smith & Wesson Revolver Company" in 18 ...

factory in Springfield, Massachusetts and was presented with a fully engraved, carved pearl grip, cased Smith & Wesson Model 3 revolver. The gun and case cost the factory $400 but it was a worthwhile investment, as the company hoped for additional contracts. The Grand Duke proudly displayed his revolver as he toured the American Frontier and carried it on a buffalo hunt with the famous "Buffalo Bill" Cody.

From 7 to 14 December, he stopped in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financ ...

where he stayed at the Revere House

Revere may refer to:

Brands and companies

*Revere Ware, a U.S. cookware brand owned by World Kitchen

* Revere Camera Company, American designer of cameras and tape recorders

*Revere Copper Company

* ReVere, a car company recognised by the Classic ...

. The landau

Landau ( pfl, Landach), officially Landau in der Pfalz, is an autonomous (''kreisfrei'') town surrounded by the Südliche Weinstraße ("Southern Wine Route") district of southern Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It is a university town (since 1990 ...

which President Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

rode during his visit to Boston, was used. He was officially welcomed at the City Hall and the State House. During his stay, he visited Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

and the suburb of Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Greater Boston, Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most ...

as well as different public schools in the Boston area, being extensively briefed on the American education system. Other highlights were the battlefield of Bunker Hill and the visit to the shipyards of Charlestown, Massachusetts

Charlestown is the oldest neighborhood in Boston, Massachusetts, in the United States. Originally called Mishawum by the Massachusett tribe, it is located on a peninsula north of the Charles River, across from downtown Boston, and also adjoins ...

.

Alexei also attended a music festival where 1,200 school children composed the great choir. At the festival, a grand march of welcome, specially composed by Julius Eichberg

Julius Eichberg (13 June 1824 – 19 January 1893) was a German-born composer, musical director and educator who worked mostly in Boston, Massachusetts.

Biography

Julius Eichberg was born in Düsseldorf, Germany to a Jewish family. His first mu ...

and dedicated to "His Imperial Highness", was presented

A ball in honor of the Grand Duke took place at the Boston Theatre :''See Federal Street Theatre for an earlier theatre known also as the Boston Theatre''

The Boston Theatre was a theatre in Boston, Massachusetts. It was first built in 1854 and operated as a theatre until 1925. Productions included performances by ...

. The audit of the expenses shows that the cost of ball was $14,678.58 (equivalent of $750,000 today), with $8,916.29 being covered by the sale of the tickets and other receipts

Detour to Canada

On 17 December, Alexei left by train to Canada. He first stopped inMontreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, where he had breakfast with the mayor of the city, and then visited Lachine, Quebec

Lachine () is a borough (''arrondissement'') within the city of Montreal on the Island of Montreal in southwestern Quebec, Canada. It was an autonomous city until the municipal mergers in 2002.

History

Lachine, apparently from the French term ' ...

. He then passed through Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

and Toronto, finally reaching Clifton Hill, Niagara Falls

Clifton Hill is one of the major tourist promenades in Niagara Falls, Ontario. The street, close to Niagara Falls and the Niagara River, leads from River Road on the Niagara Parkway to intersect with Victoria Avenue, and contains a number of gif ...

on 22 December 1871 by the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company that linked London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 mill ...

. On his way, the train stopped in Hamilton, Ontario

Hamilton is a port city in the Canadian province of Ontario. Hamilton has a population of 569,353, and its census metropolitan area, which includes Burlington and Grimsby, has a population of 785,184. The city is approximately southwest of ...

where he received a telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

from Queen Victoria, notifying him that the Prince of Wales had recovered from his illness. From Clifton Hill the party left by sleigh

A sled, skid, sledge, or sleigh is a land vehicle that slides across a surface, usually of ice or snow. It is built with either a smooth underside or a separate body supported by two or more smooth, relatively narrow, longitudinal runners s ...

s for a visit to the Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the border between the province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York in the United States. The largest of the three is Horseshoe Fall ...

. After having dressed in oil-skinned suits for fishermen at sea, the party also went under the falls. He then crossed the Niagara River

The Niagara River () is a river that flows north from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario. It forms part of the border between the province of Ontario in Canada (on the west) and the state of New York in the United States (on the east). There are diffe ...

over a new suspension bridge

A suspension bridge is a type of bridge in which the deck is hung below suspension cables on vertical suspenders. The first modern examples of this type of bridge were built in the early 1800s. Simple suspension bridges, which lack vertical ...

and then visited the United States part of the falls.

Midwest

On 23 December 1871, Alexei left by train forBuffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, where he spent Christmas. On 26 December, he arrived in Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U ...

where he visited the iron mills and other factories in Newburgh Heights, Ohio

Newburgh Heights is a village in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, United States. The population was 2,167 at the 2010 census.

Geography

Newburgh Heights is surrounded on three sides (west, north and east) by Washington Park Blvd, north of Harvard Avenue, ...

. He then reviewed the Cleveland Fire Department and visited the National Inventors’ Exhibition. He then stopped in Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at ...

on his way to Chicago, where he arrived on 30 December.

The city was recovering from the great fire. Joseph Medill

Joseph Medill (April 6, 1823March 16, 1899) was a Canadian-American newspaper editor, publisher, and Republican Party politician. He was co-owner and managing editor of the ''Chicago Tribune'', and he was Mayor of Chicago from after the Great Chi ...

, mayor of Chicago, had written to the Grand Duke:

"We have but little to exhibit but the ruins and débris of a great and beautiful city and an undaunted people struggling with adversity to relieve their overwhelming misfortunes."

He visited the destroyed part of the city and was impressed by the rhythm of the reconstruction. He gave US$5,000 (equivalent to $250,000 today) in gold to the homeless people of Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

. Alexei also visited the stockyards and a pork processing plant.

As the Tremont House Hotel had been burnt to the ground, he was accommodated in the New Tremont House which had opened on Michigan Avenue, where he was awarded the "Freedom of the City

The Freedom of the City (or Borough in some parts of the UK) is an honour bestowed by a municipality upon a valued member of the community, or upon a visiting celebrity or dignitary. Arising from the medieval practice of granting respected ...

". On New Year's Day

New Year's Day is a festival observed in most of the world on 1 January, the first day of the year in the modern Gregorian calendar. 1 January is also New Year's Day on the Julian calendar, but this is not the same day as the Gregorian one. Wh ...

General Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close as ...

initiated him into the American custom of making "New Year's calls upon the ladies".

From 2 to 4 January he visited Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at th ...

and on 5 January he arrived in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, whic ...

, where he stayed for over a week.

In St. Louis, Alexei attended the burlesque show ''Blue Beard'' in which Lydia Thompson

Lydia Thompson (born Eliza Thompson; 19 February 1838 – 17 November 1908), was an English dancer, comedian, actor and theatrical producer.

From 1852, as a teenager, she danced and performed in pantomimes, in the UK and then in Europe and soo ...

, a 36-year-old actress was singing a tune "If Ever I Cease to Love". It is claimed that he was fascinated both by the actress and the song. Supposedly, she had also sung the number privately for the duke during a rendezvous. Later, while in St. Louis, Alexei became particularly enamored of one of his dance partners, a lady called Sallie Shannon of Lawrence, Kansas

Lawrence is the county seat of Douglas County, Kansas, United States, and the sixth-largest city in the state. It is in the northeastern sector of the state, astride Interstate 70, between the Kansas and Wakarusa Rivers. As of the 2020 census ...

.Norman E. Saul ''Concord and Conflict: The United States and Russia, 1867–1914'' University of Kansas Press, 1996,

Finally on 12 January he arrived in Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County, Nebraska, Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. List of ...

Trip to the hunting grounds

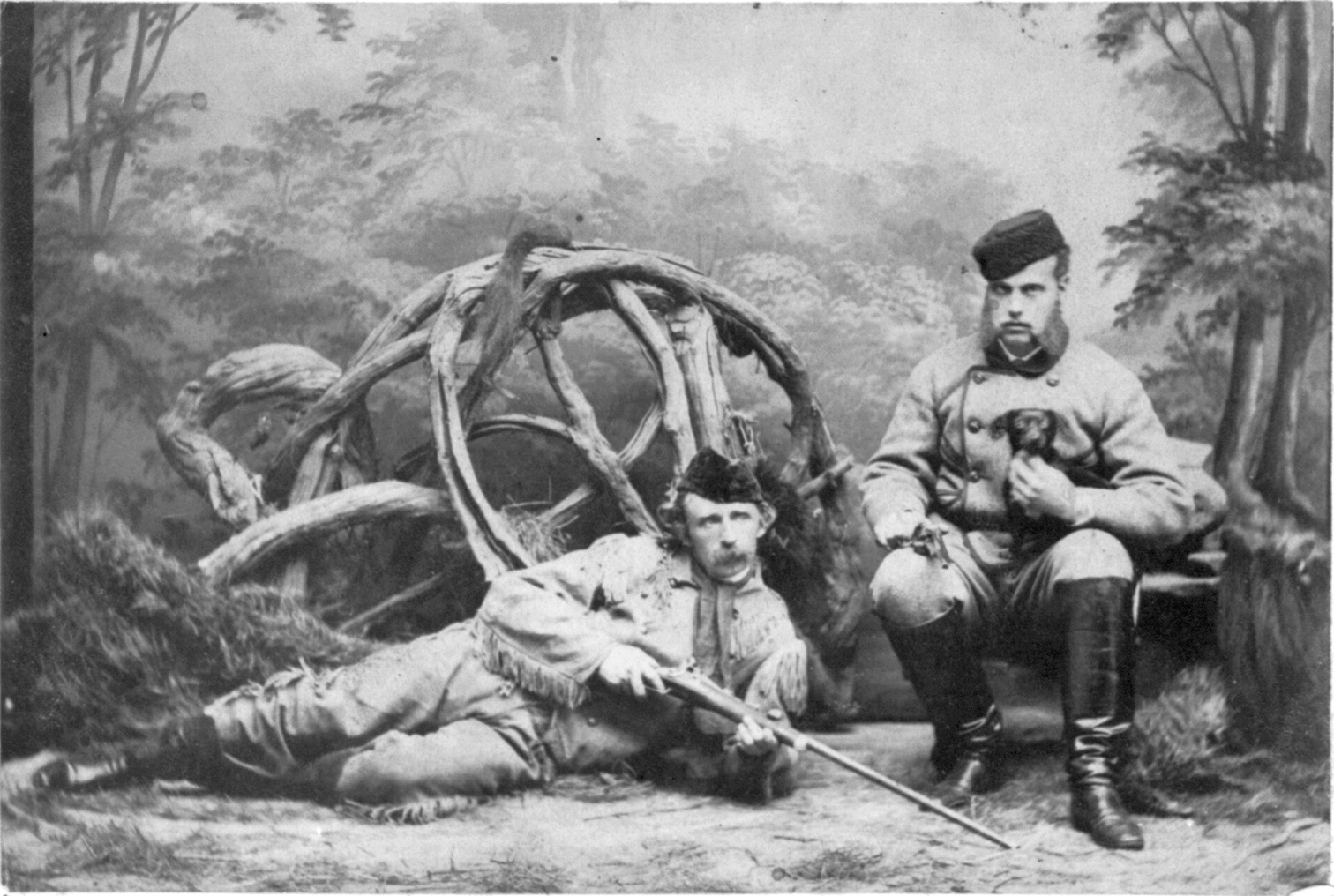

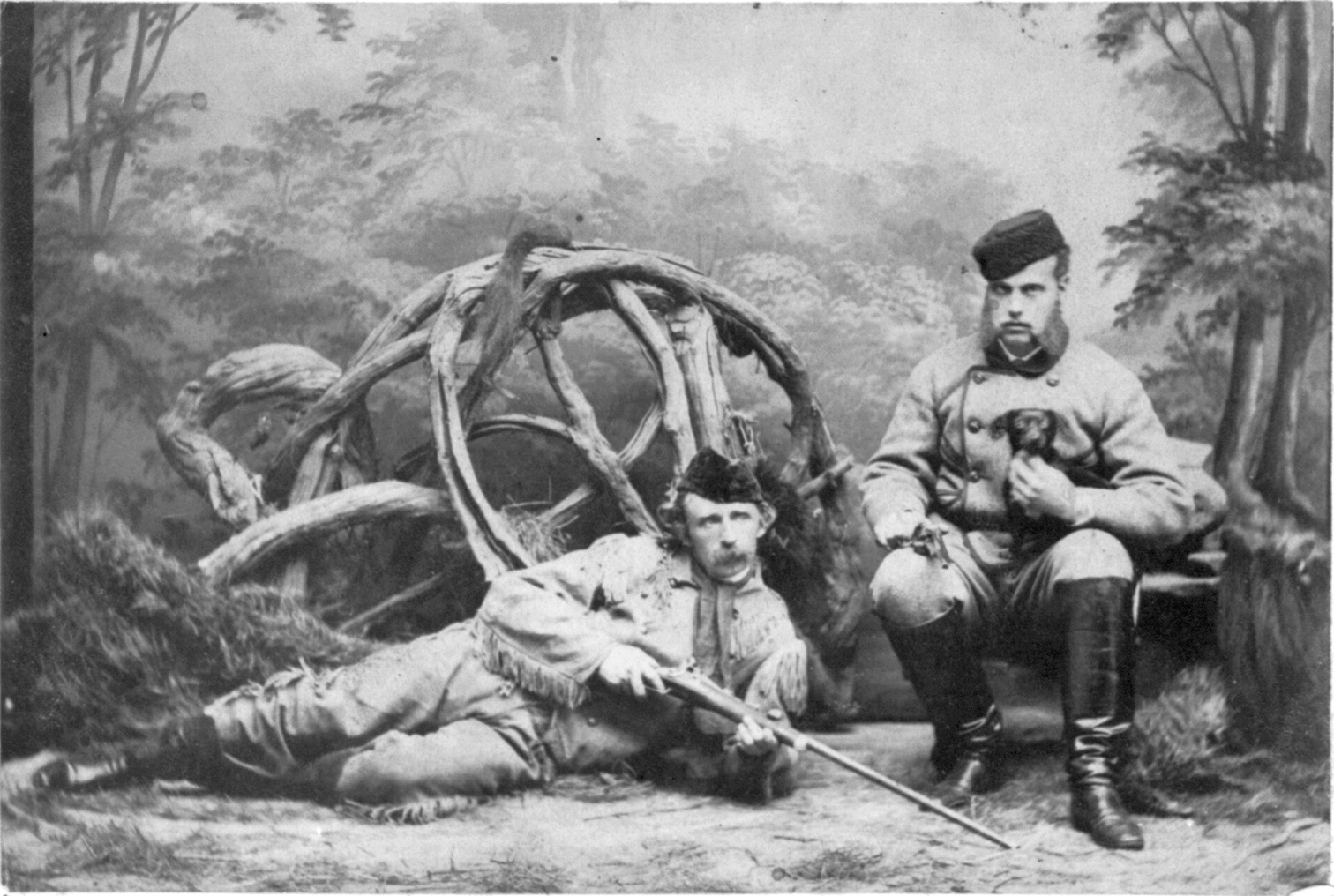

Preparations for the hunt were extensive and had been carried out under the command of GeneralJoel Palmer

General Joel Palmer (October 4, 1810 – June 9, 1881) was an American pioneer of the Oregon Territory in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. He was born in Canada, and spent his early years in New York and Pennsylvania before serving ...

. Two companies of infantry in wagons, two companies of cavalry, the cavalry's regimental band, outriders, night herders, couriers, cooks had been mobilized for the event.

The Grand Duke in the company of General Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close as ...

, General Edward Ord

Edward Otho Cresap Ord (October 18, 1818 – July 22, 1883) was an American engineer and United States Army officer who saw action in the Seminole War, the Indian Wars, and the American Civil War. He commanded an army during the final days of the ...

, and Lt. Colonel (Brevet Major General) George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his clas ...

, the latter having been selected to be grand marshal of the hunt, arrived at Fort McPherson

Fort McPherson was a U.S. Army military base located in Atlanta, Georgia, bordering the northern edge of the city of East Point, Georgia. It was the headquarters for the U.S. Army Installation Management Command, Southeast Region; the U.S ...

on 13 January 1872, by a special train provided by the Pennsylvania Railroad Company

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

. They were greeted by an enthusiastic crowd, headed by Buffalo Bill

William Frederick Cody (February 26, 1846January 10, 1917), known as "Buffalo Bill", was an American soldier, bison hunter, and showman. He was born in Le Claire, Iowa Territory (now the U.S. state of Iowa), but he lived for several years ...

. After speeches, party set out for the hunting grounds lead by Buffalo Bill's partner Texas Jack Omohundro

John Baker Omohundro (July 27, 1846 – June 28, 1880), also known as "Texas Jack", was an American frontier scout, actor, and cowboy. Born in rural Virginia, he served the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. He late ...

.

The Duke and General Sheridan rode in an open carriage, drawn by four horses. Buffalo Bill escorted the party with five ambulances, a light wagon for luggage, three wagons of "champagne and royal spirits" and fifteen to twenty extra saddle horses. The entire trip covered about 50 miles and took approximately eight hours.

The camp consisted of two hospital tents (used as dining tent), ten wall tents and tents for servants and soldiers. Three wall tents were floored and the Alexei's was carpeted with oriental rugs. Box stoves and Sibley stoves were provided for the tents.

Cody had discussed the hunt with Spotted Tail

Spotted Tail (Siŋté Glešká pronounced ''gleh-shka''; birth name T'at'aŋka Napsíca "Jumping Buffalo"Ingham (2013) uses 'c' to represent 'č'. ); born c. 1823 – died August 5, 1881) was a Brulé Lakota tribal chief. Although a great war ...

, chief of the Brulé

The Brulé are one of the seven branches or bands (sometimes called "sub-tribes") of the Teton (Titonwan) Lakota American Indian people. They are known as Sičhą́ǧu Oyáte (in Lakȟóta) —Sicangu Oyate—, ''Sicangu Lakota, o''r "Burnt ...

Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

*Lakota, Iowa

*Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

*Lakot ...

, who had agreed to meet the "great chief from across the water who was coming there to visit him." About 600 warriors of different Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

tribes, led by Spotted Tail, War Bonnet, Black Hat, Red Leaf, Whistler and Pawnee Killer, assembled to greet Alexei at the hunting camp. They had been provided with ten thousand rations of flour, sugar, coffee, and 1,000 pounds of tobacco for their trouble – twenty-five wagon loads in all.

At the start of the party, Spotted Tail, dressed in a suit, which didn't fit him, with an army belt upside down and an extremely awkward look was introduced to the Grand Duke. Then the Indian chief extended his hand, and greeted him in Lakota saying "How

How may refer to:

* How (greeting), a word used in some misrepresentations of Native American/First Nations speech

* How, an interrogative word in English grammar

Art and entertainment Literature

* ''How'' (book), a 2007 book by Dov Seid ...

."

For the amusement of Alexei the Indians staged exercises of horsemanship, lance-throwing and bow-shooting. Then there was a sham fight, showing the Indian mode of warfare, closing up with a grand war dance. It was noticed that Alexei paid considerable attention to a good-looking Indian maiden. Concerned that his mother, Empress Maria Alexandrovna, might receive reports of his flirtations, he wrote her from St. Louis: "Regarding my success with American ladies about which so much is written in the newspapers, I can openly say, that this is complete nonsense. They looked on me from the beginning as they would look on a wild animal, as on a crocodile or other unusual beast." .

A dispute broke out, but Alexei was able to calm down the fight with gifts of red and green blankets, ivory-handled hunting knives and a large bag of silver dollars. A formal council took place in Sheridan's tent and a peace pipe was passed around. Spotted Tail seized the chance to press his demand for the right to hunt freely south of the Platte River

The Platte River () is a major river in the State of Nebraska. It is about long; measured to its farthest source via its tributary, the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, which itsel ...

and for more than one store in which to trade.

Buffalo hunt

The big hunt took place on Alexei's 22nd birthday, 14 January 1872. He carried a Russian hunting knife and an American revolver bearing the coats-of-arms of the United States and Russia on the handle, which he had recently received as a present. The hunting party approached buffalo herd several miles up the Red Willow Creek. Alexei rode Buffalo Bill's celebrated buffalo horse "Buckskin Joe", which had been trained to ride at full gallop with a target so that the best shot could be made. As soon as a herd of buffalo was seen, some two miles away, Alexei wanted to make a charge but was restrained by Bill. The party moved to the windward and gradually approached the herd. Within a hundred yards of the fleeing buffalo, Alexei, not accustomed to shooting from a running horse, fired, but missed. Buffalo Bill rode up close beside him, handed him his own famed .48-caliber rifle, "Lucretia", the one with which he claimed to have killed 4,200 buffalo, and advised him not to fire until he was on the flank of the buffalo. When Alexei tried again, he brought down his game. The hide of the dead buffalo was carefully removed and dressed; Alexei took it home as a souvenir of his hunt on the western plains. Twenty to thirty animals were killed on the first day of the hunt. The party returned early to camp, where there was a liberal supply of champagne and other beverages provided, and the evening was spent in frontier style. The next morning Spotted Tail requested the Grand Duke to hunt by the side of Two Lance, chief of theNakota

Nakota (or Nakoda or Nakona) is the endonym used by those '' Assiniboine'' Indigenous people in the US, and by the Stoney People, in Canada.

The Assiniboine branched off from the Great Sioux Nation (aka the ''Oceti Sakowin'') long ago and mo ...

Sioux tribe, so that he could see a demonstration of the Indian way of hunting. Coming up to a herd of buffalo, Two Lance demonstrated his skill by killing a large animal with one arrow which passed entirely through the body of the running buffalo. The arrow was preserved and given to Alexei. He killed two buffalo, one of them at 100 paces distance, with a pistol shot.

On the conclusion of the hunt, when returning to Fort McPherson, General Sheridan proposed that Buffalo Bill take the reins and show Alexei the old style of stage driving over the plains with the horses at full gallop. The heavy ambulance bounded over the rough prairie, while the occupants could hardly keep their seats. Alexei was pleased with his hunting trip. When he and Bill parted in Fort McPherson, Alexei presented him with a fur coat and expensive cuff links.

From there the train continued to

From there the train continued to Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the United ...

where Alexei arrived on 17 January. While in Denver, he attended an honorary ball sponsored by the Pioneer Club and visited some mines. He apparently loved the new sport he had just learned and hunted buffalo again near Colorado Springs

Colorado Springs is a home rule municipality in, and the county seat of, El Paso County, Colorado, United States. It is the largest city in El Paso County, with a population of 478,961 at the 2020 United States Census, a 15.02% increase since ...

, on his return trip from Denver through Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to ...

to St. Louis. However, the horses used to hunt in eastern Colorado were cavalry mounts and unaccustomed to buffalo; several hunters were injured during the resulting confusion. Alexei was unhurt and succeeded in killing as many as 25 buffalo. He even shot a few more from the train on its way across western Kansas toward Topeka

Topeka ( ; Kansa: ; iow, Dópikˀe, script=Latn or ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Kansas and the seat of Shawnee County. It is along the Kansas River in the central part of Shawnee County, in northeast Kansas, in the Central ...

, which was reached on 22 January. It is claimed that, by the time they reached St. Louis, the party's supply of caviar and champagne had been exhausted.Walt Sehner"The Grand Duke Alexis"

''McCook Gazette'', Monday, 31 December 2007 ] General Custer became one of the Duke's best friends. He accompanied him and his entourage through Kansas, to St. Louis, New Orleans, and finally to Florida. They continued to correspond with one another up until Custer's death. In the United States, the hunt is remembered as "The Great Royal Buffalo Hunt". Starting from the year 2000,

Hayes Center, Nebraska

Hayes Center is a village in Hayes County, Nebraska, United States, which has served as that county's county seat since 1885. Its population, according to the 2010 U.S. census, was 214.

History

Hayes Center was founded in 1885. It was named from ...

organizes each year the "Grand Duke Alexis Rendezvous" featuring a reenactment of the buffalo hunt.

Alexei received as a gift from chief Spotted Tail an Indian wigwam

A wigwam, wickiup, wetu (Wampanoag), or wiigiwaam (Ojibwe, in syllabics: ) is a semi-permanent domed dwelling formerly used by certain Native American tribes and First Nations people and still used for ceremonial events. The term ''wickiup' ...

and a bow and arrows. He took them back to St. Petersburg. At present they are kept at the museum in Tver

Tver ( rus, Тверь, p=tvʲerʲ) is a city and the administrative centre of Tver Oblast, Russia. It is northwest of Moscow. Population:

Tver was formerly the capital of a powerful medieval state and a model provincial town in the Russia ...

. In memory of his adventures in America, Alexei organized every year a special entertainment. The actors arrived to a village of tents in old carriages drawn by heavy horses. On the palace's lake there were "Indian" pirogue

A pirogue ( or ), also called a piragua or piraga, is any of various small boats, particularly dugouts and native canoes. The word is French and is derived from Spanish , which comes from the Carib '. Description

The term 'pirogue' does not ...

s. Men with swords and tomahawks danced with women dressed in long old skirts. The performance was supposed to give the attendance an image of the American Old West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

.

Southern states

While in St. Louis, Alexei made a short visit toCincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state lin ...

on 26 January On 28 January he left by train for Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana borde ...

, where he visited the Mammoth Cave

Mammoth Cave National Park is an American national park in west-central Kentucky, encompassing portions of Mammoth Cave, the longest cave system known in the world.

Since the 1972 unification of Mammoth Cave with the even-longer system under F ...

He continued his trip by steamer, arriving on 2 February 1872 in Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the County seat, seat of Shelby County, Tennessee, Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 Uni ...

aboard the ''Great Republic''. After visiting the city he left on 8 February aboard the ''James Howard'' and after a stop in Vicksburg Vicksburg most commonly refers to:

* Vicksburg, Mississippi, a city in western Mississippi, United States

* The Vicksburg Campaign, an American Civil War campaign

* The Siege of Vicksburg, an American Civil War battle

Vicksburg is also the name of ...

he finally arrived in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Arriving in Japan on 15 October 1872, the Russian squadron cast anchor in

Arriving in Japan on 15 October 1872, the Russian squadron cast anchor in

Besides being the head of Russia's fleets, Alexei was also in command of the

/ref> The Grand Duke was suspected of being involved in the misappropriation. At the outbreak of the

His critics talked of Alexei's life as consisting of "fast women and slow ships", referring to his womanizing and the defeat of the Russian navy by the Japanese. Away from his desk, Alexei devoted his time to the good things of life. He entertained generously and collected fine silver and other works of art to adorn his palace.Zeepvat, ''Romanov Autumn'', p. 150 Sometimes he designed his own clothes. A womanizer, he spent his vacations in Paris or in

His critics talked of Alexei's life as consisting of "fast women and slow ships", referring to his womanizing and the defeat of the Russian navy by the Japanese. Away from his desk, Alexei devoted his time to the good things of life. He entertained generously and collected fine silver and other works of art to adorn his palace.Zeepvat, ''Romanov Autumn'', p. 150 Sometimes he designed his own clothes. A womanizer, he spent his vacations in Paris or in

New Orleans

In New Orleans Alexei attended the 1872 Mardi Gras celebrations, where he was guest of honor reviewing the inauguralRex parade

Rex (founded 1872) is a New Orleans Carnival Krewe which stages one of the city's most celebrated parades on Mardi Gras Day. Rex is Latin for "King", and Rex reigns as "The King of Carnival".

History and formation

Rex was organized by New Or ...

.

There are many legends related to the Grand Duke's visit to New Orleans. It has been claimed that local business leaders had planned the first daytime parade to honor him, but this was not true. New Orleans was struggling to recover from the lingering effects of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

. At the same time, many city leaders saw the need to bring some order to the chaotic street parades of Mardi Gras day. They had planned the parade all along and took the opportunity to capitalize on Alexei's visit. A new krewe

A krewe (pronounced "crew") is a social organization that puts on a parade or ball for the Carnival season. The term is best known for its association with Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans, but is also used in other Carnival celebrations a ...

of prominent citizens was formed, calling itself the School of Design, and its ruler was to be Rex (the organization is now known as the "Rex Organization"). The group of young men who founded the Rex Organization hoped not only to entertain the Grand Duke, but also to create a daytime parade that would be attractive and fun for the citizens of the city and their guests. They selected one of their members, Lewis J. Salomon, the organization's fund-raiser to be the first Rex, King of Carnival. Before he could begin his reign, he had to borrow a crown, scepter, and costume from Lawrence Barrett

Lawrence Barrett (April 4, 1838 – March 20, 1891) was an American stage actor.

Biography

A native of Paterson, New Jersey, Barrett was born in 1838 to Mary Agnes (née Read) Barrett and tailor Thomas Barrett, Irish immigrants who had settled ...

, a distinguished Shakespearean actor who was performing ''Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Bat ...

'' at the Varieties Theater.

At the same time, Lydia Thompson's tour had reached New Orleans and the Bluebeard burlesque was staged at the Academy of Music on St. Charles Avenue. Rumours of the courtship between Alexei and the actress had reached New Orleans and were amplified mainly to ensure a full house. Alexei had already seen the performance and didn't attend, hanging out at the Jockey Club. Besides, his preferences had shifted and he was captivated by the diminutive actress Lotta Crabtree

Charlotte Mignon "Lotta" Crabtree (November 7, 1847 – September 25, 1924), also known mononymously as Lotta, was an American actress, entertainer, comedian, and philanthropist.

Crabtree was born in New York City and raised in the gold mining ...

who had one of the main roles in the play ''The Little Detective''. Though the encounter was brief, Alexei sent her a gift in Memphis, her next stop after New Orleans.

Alexei attended the Rex parade. According to legend, the song "If Ever I Cease to Love", was chosen as anthem of the Rex parade, because it was claimed to be his favorite tune. Actually, the silly song had been written by George Leybourne

George Leybourne (17 March 1842 – 15 September 1884) was a '' Lion comique'' of the British Victorian music hall who, for much of his career, was known by the title of one of his songs, " Champagne Charlie". Another of his songs, and one tha ...

and published in London in 1871. The song was already popular in New Orleans before the first Rex parade in 1872. the local adaptation of the lyrics was likely done local journalist E. C. Hancock

E is the fifth letter of the Latin alphabet.

E or e may also refer to:

Commerce and transportation

* €, the symbol for the euro, the European Union's standard currency unit

* ℮, the estimated sign, an EU symbol indicating that the weig ...

whose newspaper had already published a spoof of the song in 1871. The lyrics of the song were adapted to the occasion and changed to: