Alexander Graham Bell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alexander Graham Bell (; born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born

Bell and his partners, Hubbard and Sanders, offered to sell the patent outright to Western Union for $100,000, equal to $ today, but it did not work (according to an apocryphal story, the president of Western Union balked, countering that the telephone was nothing but a toy). Two years later, he told colleagues that if he could get the patent for $25 million (equal to $ today), he would consider it a bargain. By then, the Bell company no longer wanted to sell the patent. Bell's investors became millionaires while he fared well from residuals and at one point had assets of nearly $1 million.

Bell began a series of public demonstrations and lectures to introduce the new invention to the scientific community as well as the general public. A short time later, his demonstration of an early telephone prototype at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in

Bell and his partners, Hubbard and Sanders, offered to sell the patent outright to Western Union for $100,000, equal to $ today, but it did not work (according to an apocryphal story, the president of Western Union balked, countering that the telephone was nothing but a toy). Two years later, he told colleagues that if he could get the patent for $25 million (equal to $ today), he would consider it a bargain. By then, the Bell company no longer wanted to sell the patent. Bell's investors became millionaires while he fared well from residuals and at one point had assets of nearly $1 million.

Bell began a series of public demonstrations and lectures to introduce the new invention to the scientific community as well as the general public. A short time later, his demonstration of an early telephone prototype at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in

On July 11, 1877, a few days after the Bell Telephone Company was established, Bell married Mabel Hubbard (1857–1923) at the Hubbard estate in

On July 11, 1877, a few days after the Bell Telephone Company was established, Bell married Mabel Hubbard (1857–1923) at the Hubbard estate in

Although Alexander Graham Bell is most often associated with the invention of the telephone, his interests were extremely varied. According to one of his biographers, Charlotte Gray, Bell's work ranged "unfettered across the scientific landscape" and he often went to bed voraciously reading the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', scouring it for new areas of interest. The range of Bell's inventive genius is represented only in part by the 18 patents granted in his name alone and the 12 he shared with his collaborators. These included 14 for the telephone and telegraph, four for the photophone, one for the phonograph, five for aerial vehicles, four for "hydroairplanes", and two for

Although Alexander Graham Bell is most often associated with the invention of the telephone, his interests were extremely varied. According to one of his biographers, Charlotte Gray, Bell's work ranged "unfettered across the scientific landscape" and he often went to bed voraciously reading the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', scouring it for new areas of interest. The range of Bell's inventive genius is represented only in part by the 18 patents granted in his name alone and the 12 he shared with his collaborators. These included 14 for the telephone and telegraph, four for the photophone, one for the phonograph, five for aerial vehicles, four for "hydroairplanes", and two for

Bell and his assistant

Bell and his assistant

The March 1906 ''

The March 1906 ''

In 1891, Bell had begun experiments to develop motor-powered heavier-than-air aircraft. The AEA was first formed as Bell shared the vision to fly with his wife, who advised him to seek "young" help as Bell was at the age of 60.

In 1898, Bell experimented with tetrahedral box kites and wings constructed of multiple compound tetrahedral kites covered in maroon silk. The tetrahedral wings were named ''Cygnet'' I, II, and III, and were flown both unmanned and manned (''Cygnet I'' crashed during a flight carrying Selfridge) in the period from 1907 to 1912. Some of Bell's kites are on display at the Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site.

Bell was a supporter of aerospace engineering research through the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), officially formed at Baddeck, Nova Scotia, in October 1907 at the suggestion of his wife Mabel and with her financial support after the sale of some of her real estate. The AEA was headed by Bell and the founding members were four young men: American Glenn H. Curtiss, a motorcycle manufacturer at the time and who held the title "world's fastest man", having ridden his self-constructed motor bicycle around in the shortest time, and who was later awarded the Scientific American Trophy for the first official one-kilometre flight in the

In 1891, Bell had begun experiments to develop motor-powered heavier-than-air aircraft. The AEA was first formed as Bell shared the vision to fly with his wife, who advised him to seek "young" help as Bell was at the age of 60.

In 1898, Bell experimented with tetrahedral box kites and wings constructed of multiple compound tetrahedral kites covered in maroon silk. The tetrahedral wings were named ''Cygnet'' I, II, and III, and were flown both unmanned and manned (''Cygnet I'' crashed during a flight carrying Selfridge) in the period from 1907 to 1912. Some of Bell's kites are on display at the Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site.

Bell was a supporter of aerospace engineering research through the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), officially formed at Baddeck, Nova Scotia, in October 1907 at the suggestion of his wife Mabel and with her financial support after the sale of some of her real estate. The AEA was headed by Bell and the founding members were four young men: American Glenn H. Curtiss, a motorcycle manufacturer at the time and who held the title "world's fastest man", having ridden his self-constructed motor bicycle around in the shortest time, and who was later awarded the Scientific American Trophy for the first official one-kilometre flight in the

Honours and tributes flowed to Bell in increasing numbers as his invention became ubiquitous and his personal fame grew. Bell received numerous honorary degrees from colleges and universities to the point that the requests almost became burdensome. During his life, he also received dozens of major awards, medals, and other tributes. These included statuary monuments to both him and the new form of communication his telephone created, including the Bell Telephone Memorial erected in his honour in ''Alexander Graham Bell Gardens'' in Brantford, Ontario, in 1917.

Honours and tributes flowed to Bell in increasing numbers as his invention became ubiquitous and his personal fame grew. Bell received numerous honorary degrees from colleges and universities to the point that the requests almost became burdensome. During his life, he also received dozens of major awards, medals, and other tributes. These included statuary monuments to both him and the new form of communication his telephone created, including the Bell Telephone Memorial erected in his honour in ''Alexander Graham Bell Gardens'' in Brantford, Ontario, in 1917.

A large number of Bell's writings, personal correspondence, notebooks, papers, and other documents reside in both the United States Library of Congress Manuscript Division (as the ''Alexander Graham Bell Family Papers''), and at the Alexander Graham Bell Institute, Cape Breton University, Nova Scotia; major portions of which are available for online viewing.

A number of historic sites and other marks commemorate Bell in North America and Europe, including the first telephone companies in the United States and Canada. Among the major sites are:

* The Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site, maintained by

A large number of Bell's writings, personal correspondence, notebooks, papers, and other documents reside in both the United States Library of Congress Manuscript Division (as the ''Alexander Graham Bell Family Papers''), and at the Alexander Graham Bell Institute, Cape Breton University, Nova Scotia; major portions of which are available for online viewing.

A number of historic sites and other marks commemorate Bell in North America and Europe, including the first telephone companies in the United States and Canada. Among the major sites are:

* The Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site, maintained by

In 1880, Bell received the Volta Prize with a purse of 50,000 French francs (approximately US$ in today's currency) for the invention of the telephone from the French government. Among the luminaries who judged were

In 1880, Bell received the Volta Prize with a purse of 50,000 French francs (approximately US$ in today's currency) for the invention of the telephone from the French government. Among the luminaries who judged were  In 1936, the US Patent Office declared Bell first on its list of the country's greatest inventors, leading to the US Post Office issuing a commemorative stamp honouring Bell in 1940 as part of its 'Famous Americans Series'. The First Day of Issue ceremony was held on October 28 in Boston, Massachusetts, the city where Bell spent considerable time on research and working with the deaf. The Bell stamp became very popular and sold out in little time. The stamp became, and remains to this day, the most valuable one of the series.

The 150th anniversary of Bell's birth in 1997 was marked by a special issue of commemorative £1 banknotes from the Royal Bank of Scotland. The illustrations on the reverse of the note include Bell's face in profile, his signature, and objects from Bell's life and career: users of the telephone over the ages; an audio wave signal; a diagram of a telephone receiver; geometric shapes from engineering structures; representations of sign language and the phonetic alphabet; the geese which helped him to understand flight; and the sheep which he studied to understand genetics. Additionally, the Government of Canada honoured Bell in 1997 with a C$100 gold coin, in tribute also to the 150th anniversary of his birth, and with a silver dollar coin in 2009 in honour of the 100th anniversary of flight in Canada. That first flight was made by an airplane designed under Dr. Bell's tutelage, named the Silver Dart. Bell's image, and also those of his many inventions have graced paper money, coinage, and postal stamps in numerous countries worldwide for many dozens of years.

Alexander Graham Bell was ranked 57th among the 100 Greatest Britons (2002) in an official BBC nationwide poll, and among the Top Ten Greatest Canadians (2004), and the 100 Greatest Americans (2005). In 2006, Bell was also named as one of the 10 greatest Scottish scientists in history after having been listed in the National Library of Scotland's 'Scottish Science Hall of Fame'. Bell's name is still widely known and used as part of the names of dozens of educational institutes, corporate namesakes, street and place names around the world.

In 1936, the US Patent Office declared Bell first on its list of the country's greatest inventors, leading to the US Post Office issuing a commemorative stamp honouring Bell in 1940 as part of its 'Famous Americans Series'. The First Day of Issue ceremony was held on October 28 in Boston, Massachusetts, the city where Bell spent considerable time on research and working with the deaf. The Bell stamp became very popular and sold out in little time. The stamp became, and remains to this day, the most valuable one of the series.

The 150th anniversary of Bell's birth in 1997 was marked by a special issue of commemorative £1 banknotes from the Royal Bank of Scotland. The illustrations on the reverse of the note include Bell's face in profile, his signature, and objects from Bell's life and career: users of the telephone over the ages; an audio wave signal; a diagram of a telephone receiver; geometric shapes from engineering structures; representations of sign language and the phonetic alphabet; the geese which helped him to understand flight; and the sheep which he studied to understand genetics. Additionally, the Government of Canada honoured Bell in 1997 with a C$100 gold coin, in tribute also to the 150th anniversary of his birth, and with a silver dollar coin in 2009 in honour of the 100th anniversary of flight in Canada. That first flight was made by an airplane designed under Dr. Bell's tutelage, named the Silver Dart. Bell's image, and also those of his many inventions have graced paper money, coinage, and postal stamps in numerous countries worldwide for many dozens of years.

Alexander Graham Bell was ranked 57th among the 100 Greatest Britons (2002) in an official BBC nationwide poll, and among the Top Ten Greatest Canadians (2004), and the 100 Greatest Americans (2005). In 2006, Bell was also named as one of the 10 greatest Scottish scientists in history after having been listed in the National Library of Scotland's 'Scottish Science Hall of Fame'. Bell's name is still widely known and used as part of the names of dozens of educational institutes, corporate namesakes, street and place names around the world.

Also published as: * *

''The Story of A Famous Inventor.''

New York: Rogers and Fowle, 1921. * Walters, Eric. ''The Hydrofoil Mystery''. Toronto, Ontario, Canada:

''The History Of Special Education: From Isolation To Integration''.

Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 1993. .

Alexander and Mabel Bell Legacy Foundation

Alexander Graham Bell Institute at Cape Breton University

(archived 8 December 2015)

Bell Telephone Memorial

Brantford, Ontario

Bell Homestead National Historic Site

Brantford, Ontario

Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site of Canada

Baddeck, Nova Scotia

Alexander Graham Bell Family Papers at the Library of Congress

*

Science.ca profile: Alexander Graham Bell

* *

Alexander Graham Bell's notebooks

at the

"Téléphone et photophone : les contributions indirectes de Graham Bell à l'idée de la vision à distance par l'électricité"

at th

Histoire de la télévision

*

Alexander Graham Bell and the Aerial Experiment Association Photograph Collection

a

The Museum of Flight (Seattle, Washington).

Alexander Graham Bell

at

''Shaping The Future''

from the '' Heritage Minutes'' and ''Radio Minutes'' collection at HistoricaCanada.ca (1:31 audio drama, Adobe Flash required) {{DEFAULTSORT:Bell, Alexander Graham 1847 births 1922 deaths 19th-century Scottish inventors 19th-century Canadian inventors 19th-century Canadian scientists 19th-century Scottish businesspeople 19th-century Scottish scientists 19th-century Scottish engineers 20th-century American inventors 20th-century American scientists 20th-century Canadian scientists Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of University College London American agnostics American educational theorists American Eugenics Society members American physicists American recipients of the Legion of Honour American Unitarians Articles containing video clips Aviation pioneers Businesspeople from Boston Canadian activists Canadian agnostics Canadian Aviation Hall of Fame inductees Canadian educational theorists Canadian emigrants to the United States Canadian eugenicists Canadian physicists Canadian Unitarians Deaths from diabetes in Canada Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Gardiner family George Washington University trustees Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees History of telecommunications IEEE Edison Medal recipients John Fritz Medal recipients Language teachers Members of the American Philosophical Society Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences National Aviation Hall of Fame inductees National Geographic Society Officers of the Legion of Honour People educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh People from Baddeck, Nova Scotia People from Brantford Scientists from Edinburgh Scientists from Washington, D.C. Scottish agnostics Scottish emigrants to Canada Scottish emigrants to the United States Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame inductees Scottish eugenicists Scottish physicists Scottish Unitarians Smithsonian Institution people People on Irish postage stamps

Canadian-American

Canadian Americans () are Citizenship of the United States, American citizens or in some uses residents whose ancestry is wholly or partly Canadians, Canadian, or citizens of either country who hold dual citizenship. Today, many Canadian American ...

inventor, scientist, and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone

A telephone, colloquially referred to as a phone, is a telecommunications device that enables two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most ...

. He also co-founded the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) in 1885.

Bell's father, grandfather, and brother had all been associated with work on elocution and speech, and both his mother and wife were deaf, profoundly influencing Bell's life's work. His research on hearing and speech further led him to experiment with hearing devices, which eventually culminated in his being awarded the first U.S. patent for the telephone, on March 7, 1876. Bell considered his invention an intrusion on his real work as a scientist and refused to have a telephone in his study.

Many other inventions marked Bell's later life, including ground-breaking work in optical telecommunications, hydrofoils, and aeronautics

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design process, design, and manufacturing of air flight-capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft and rockets within the atmosphere.

While the term originally referred ...

. Bell also had a strong influence on the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society, headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, natural sc ...

and its magazine

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

while serving as its second president from 1898 to 1903.

Beyond his work in engineering, Bell had a deep interest in the emerging science of heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic infor ...

. His work in this area has been called "the soundest, and most useful study of human heredity proposed in nineteenth-century America ... Bell's most notable contribution to basic science, as distinct from invention."

Early life

Bell was born inEdinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, Scotland, on March 3, 1847, to Alexander Melville Bell

Alexander Melville Bell (1 March 18197 August 1905) was a teacher and researcher of articulatory phonetics, physiological phonetics and was the author of numerous works on orthoepy and elocution.

Additionally he was also the creator of Visible ...

, a phonetician, and Eliza Grace Bell (''née'' Symonds). The family home was on South Charlotte Street in Edinburgh, where a stone inscription marks it as Bell's birthplace. He had two brothers: Melville James Bell (1845–1870) and Edward Charles Bell (1848–1867), both who died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. He was born as just "Alexander Bell". At age 10, however, he made a plea to his father to have a middle name like his two brothers. For his 11th birthday, his father acquiesced and allowed him to adopt the name "Graham", chosen out of respect for Alexander Graham, a Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

being treated by his father who was also a family friend. To close relatives and friends he remained "Aleck". Bell and his siblings attended a Presbyterian Church in their youth.

First invention

As a child, Bell displayed a curiosity about his world; he gathered botanical specimens and ran experiments at an early age. His best friend was Ben Herdman, a neighbour whose family operated a flour mill. At the age of 12, Bell built a homemade device that combined rotating paddles with sets of nail brushes, creating a simple dehusking machine that was put into operation at the mill and used steadily for a number of years. In return, Ben's father John Herdman gave both boys the run of a small workshop in which to "invent". From his early years, Bell showed a sensitive nature and a talent for art, poetry, and music that his mother encouraged. With no formal training, he mastered the piano and became the family's pianist. Though normally quiet and introspective, he revelled in mimicry and "voice tricks" akin to ventriloquism that entertained family guests. Bell was also deeply affected by his mother's gradual deafness (she began to lose her hearing when he was 12), and learned a manual finger language so he could sit at her side and tap out silently the conversations swirling around the family parlour. He also developed a technique of speaking in clear, modulated tones directly into his mother's forehead, whereby she would hear him with reasonable clarity. Bell's preoccupation with his mother's deafness led him to studyacoustics

Acoustics is a branch of physics that deals with the study of mechanical waves in gases, liquids, and solids including topics such as vibration, sound, ultrasound and infrasound. A scientist who works in the field of acoustics is an acoustician ...

.

His family was long associated with the teaching of elocution: his grandfather, Alexander Bell, in London, his uncle in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, and his father, in Edinburgh, were all elocutionists. His father published a variety of works on the subject, several of which are still well known, especially ''The Standard Elocutionist'' (1860), which appeared in Edinburgh in 1868. ''The Standard Elocutionist'' appeared in 168 British editions and sold over 250,000 copies in the United States alone. It explains methods to instruct deaf-mutes (as they were then known) to articulate words and read other people's lip movements to decipher meaning. Bell's father taught him and his brothers not only to write Visible Speech but to identify any symbol and its accompanying sound. Bell became so proficient that he became a part of his father's public demonstrations and astounded audiences with his abilities. He could decipher Visible Speech representing virtually every language, including Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

, and even Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

, accurately reciting written tracts without any prior knowledge of their pronunciation.

Education

As a young child, Bell, like his brothers, was schooled at home by his father. At an early age, he was enrolled at the Royal High School in Edinburgh. But he left at age 15, having completed only the first four forms. His school record was undistinguished, marked by absenteeism and lacklustre grades. His main interest remained in the sciences, especially biology, while he treated other school subjects with indifference, to his father's dismay. Upon leaving school, Bell travelled to London to live with his grandfather, Alexander Bell, on Harrington Square. During the year he spent with his grandfather, a love of learning was born, with long hours spent in serious discussion and study. The elder Bell took great efforts to have his young pupil learn to speak clearly and with conviction, attributes he would need to become a teacher himself. At age 16, Bell secured a position as a "pupil-teacher" of elocution and music at Weston House Academy inElgin, Moray

Elgin ( ; ; ) is a historic town (former cathedral city) and formerly a royal burgh in Moray, Scotland. It is the administrative and commercial centre for Moray. The town originated to the south of the River Lossie on the higher ground above th ...

, Scotland. Although enrolled as a student in Latin and Greek, he instructed classes himself in return for board and £10 per session. The next year, he attended the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

, joining his brother Melville, who had enrolled there the previous year. In 1868, Bell completed his matriculation exams and was accepted for admission to University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

, though he did not complete his studies, as his family emigrated to Canada in 1870 following the deaths of his brothers Edward and Melville from tuberculosis.

First experiments with sound

Bell's father encouraged his interest in speech and, in 1863, took his sons to see a uniqueautomaton

An automaton (; : automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions. Some automata, such as bellstrikers i ...

developed by Sir Charles Wheatstone

Sir Charles Wheatstone (; 6 February 1802 – 19 October 1875) was an English physicist and inventor best known for his contributions to the development of the Wheatstone bridge, originally invented by Samuel Hunter Christie, which is used to m ...

based on the earlier work of Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen. The rudimentary "mechanical man" simulated a human voice. Bell was fascinated by the machine, and after he obtained a copy of von Kempelen's book, published in German, and had laboriously translated it, he and Melville built their own automaton head. Their father, highly interested in their project, offered to pay for any supplies and spurred the boys on with the enticement of a "big prize" if they were successful. While his brother constructed the throat and larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ (anatomy), organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal ...

, Bell tackled the more difficult task of recreating a realistic skull. His efforts resulted in a remarkably lifelike head that could "speak", albeit only a few words. The boys would carefully adjust the "lips" and when a bellows forced air through the windpipe, a very recognizable ''Mama'' ensued, to the delight of neighbours who came to see the invention.

Intrigued by the results of the automaton, Bell continued to experiment with a live subject, the family's Skye Terrier, Trouve. After he taught it to growl continuously, Bell would reach into its mouth and manipulate the dog's lips and vocal cords to produce a crude-sounding "Ow ah oo ga ma ma". With little convincing, visitors believed his dog could articulate "How are you, grandmama?" Indicative of his playful nature, his experiments convinced onlookers that they saw a "talking dog". These initial forays into experimentation with sound led Bell to undertake his first serious work on the transmission of sound, using tuning forks to explore resonance

Resonance is a phenomenon that occurs when an object or system is subjected to an external force or vibration whose frequency matches a resonant frequency (or resonance frequency) of the system, defined as a frequency that generates a maximu ...

.

At age 19, Bell wrote a report on his work and sent it to philologist Alexander Ellis, a colleague of his father. Ellis immediately wrote back indicating that the experiments were similar to existing work in Germany, and also lent Bell a copy of Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (; ; 31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894; "von" since 1883) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The ...

's work, ''The Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music''.

Dismayed to find that groundbreaking work had already been undertaken by Helmholtz, who had conveyed vowel sounds by means of a similar tuning fork "contraption", Bell pored over the book. Working from his own erroneous mistranslation of a French edition, Bell fortuitously then made a deduction that would underpin all his future work on transmitting sound, reporting: "Without knowing much about the subject, it seemed to me that if vowel sounds could be produced by electrical means, so could consonants, so could articulate speech." He also later remarked: "I thought that Helmholtz had done it ... and that my failure was due only to my ignorance of electricity. It was a valuable blunder ... If I had been able to read German in those days, I might never have commenced my experiments!"

Family tragedy

In 1865, when the Bell family moved to London, Bell returned to Weston House as an assistant master and, in his spare hours, continued experiments on sound using a minimum of laboratory equipment. Bell concentrated on experimenting with electricity to convey sound and later installed atelegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

wire from his room in Somerset College to that of a friend. Throughout late 1867, his health faltered mainly through exhaustion. His brother Edward was similarly affected by tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. While Bell recovered (by then referring to himself in correspondence as "A. G. Bell") and served the next year as an instructor at Somerset College, Bath, England, his brother's condition deteriorated. Edward never recovered. Upon his brother's death, Bell returned home in 1867. Melville had married and moved out. With aspirations to obtain a degree at University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

, Bell considered his next years preparation for the degree examinations, devoting his spare time to studying.

Helping his father in Visible Speech demonstrations and lectures brought Bell to Susanna E. Hull's private school for the deaf in South Kensington, London. His first two pupils were deaf-mute girls who made remarkable progress under his tutelage. While Melville seemed to achieve success on many fronts, including opening his own elocution school, applying for a patent on an invention, and starting a family, Bell continued as a teacher. In May 1870, Melville died from complications of tuberculosis, causing a family crisis. His father had also experienced a debilitating illness earlier in life and been restored to health by convalescence in Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

. Bell's parents embarked upon a long-planned move when they realized that their remaining son was also sickly. Acting decisively, Alexander Melville Bell asked Bell to arrange for the sale of all the family property, conclude all his brother's affairs (Bell took on his last student, curing a pronounced lisp), and join his father and mother in setting out for Canada. Reluctantly, Bell also had to conclude a relationship with Marie Eccleston, who, as he had surmised, was not prepared to leave England with him.

Canada

In 1870, 23-year-old Bell travelled with his parents and his brother's widow, Caroline Margaret Ottaway, toParis, Ontario

Paris (2021 population, 14,956) is a community located in the County of Brant, Ontario, Canada. It lies just northwest from the city of Brantford at the spot where the Nith River empties into the Grand River (Ontario), Grand River. Paris was vot ...

, to stay with Thomas Henderson, a Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

minister and family friend. The Bells soon purchased a farm of at Tutelo Heights (now called Tutela Heights), near Brantford, Ontario. The property consisted of an orchard, large farmhouse, stable, pigsty, hen-house, and a carriage house, which bordered the Grand River.

At the homestead, Bell set up a workshop in the converted carriage house near what he called his "dreaming place", a large hollow nestled in trees at the back of the property above the river. Despite his frail condition upon arriving in Canada, Bell found the climate and environs to his liking and rapidly improved. He continued his interest in the study of the human voice, and when he discovered the Six Nations Reserve across the river at Onondaga, learned the Mohawk language and translated its unwritten vocabulary into Visible Speech symbols. For his work, Bell was awarded the title of Honorary Chief and participated in a ceremony where he donned a Mohawk headdress and danced traditional dances.

After setting up his workshop, Bell continued experiments based on Helmholtz's work with electricity and sound. He also modified a melodeon (a type of pump organ) to transmit its music electrically over a distance. Once the family was settled, Bell and his father made plans to establish a teaching practice and in 1871, he accompanied his father to Montreal, where Melville was offered a position to teach his System of Visible Speech.

Work with deaf people

Bell's father was invited by Sarah Fuller, principal of the Boston School for Deaf Mutes (later to become the public Horace Mann School for the Deaf) to introduce the Visible Speech System by providing training for Fuller's instructors, but he declined the post in favour of his son. Travelling toBoston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

in April 1871, Bell proved successful in training the school's instructors. He was asked to repeat the programme at the American Asylum for Deaf-mutes in Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. The city, located in Hartford County, Connecticut, Hartford County, had a population of 121,054 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 ce ...

, and the Clarke School for the Deaf in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Returning home to Brantford after six months abroad, Bell continued his experiments with his "harmonic telegraph". The basic concept behind his device was that messages could be sent through a single wire if each was transmitted at a different pitch, but work on both the transmitter and receiver was needed.

Unsure of his future, he contemplated returning to London to complete his studies, but decided to return to Boston as a teacher. His father helped him set up his private practice by contacting Gardiner Greene Hubbard, the president of the Clarke School for the Deaf for a recommendation. Teaching his father's system, in October 1872, Alexander Bell opened his "School of Vocal Physiology and Mechanics of Speech" in Boston, which attracted a large number of deaf pupils, with his first class numbering 30 students. While he was working as a private tutor, one of his pupils was Helen Keller, who came to him as a young child unable to see, hear, or speak. She later said that Bell dedicated his life to the penetration of that "inhuman silence which separates and estranges". In 1893, Keller performed the sod-breaking ceremony for the construction of Bell's new Volta Bureau, dedicated to "the increase and diffusion of knowledge relating to the deaf".

Throughout his life, Bell sought to assimilate the deaf and hard of hearing with the hearing world. He encouraged speech therapy and lip-reading over sign language. He outlined this in an 1898 paper detailing his belief that, with resources and effort, the deaf could be taught to read lips and speak (known as oralism

Oralism is the education of deaf students through oral language by using lip reading, speech, and mimicking the mouth shapes and breathing patterns of speech.Through Deaf Eyes. Diane Garey, Lawrence R. Hott. DVD, PBS (Direct), 2007. Oralism c ...

), enabling their integration with wider society. Members of the Deaf community have criticized Bell for supporting ideas that could cause the closure of dozens of deaf schools, and what some consider eugenicist

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetics, genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human Phenotype, phenotypes by ...

ideas. Bell did not support a ban on deaf people marrying each other, an idea articulated by the National Association of the Deaf (United States), but in his memoir ''Memoir upon the Formation of a Deaf Variety of the Human Race'', he observed that if deaf people tended to marry other deaf people, this could result in the emergence of a "deaf race". Ultimately, in 1880, the Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf passed a resolution mandating the teaching of oral communication and banning signing in schools.

Continuing experimentation

In 1872, Bell became professor of Vocal Physiology and Elocution at theBoston University

Boston University (BU) is a Private university, private research university in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. BU was founded in 1839 by a group of Boston Methodism, Methodists with its original campus in Newbury (town), Vermont, Newbur ...

School of Oratory. During this period, he alternated between Boston and Brantford, spending summers in his Canadian home. At Boston University, Bell was "swept up" by the excitement engendered by the many scientists and inventors living in the city. He continued his research in sound and endeavoured to find a way to transmit musical notes and articulate speech, but although absorbed by his experiments, he found it difficult to devote enough time to experimentation. With days and evenings occupied by his teaching and private classes, Bell began to stay awake late into the night, running experiment after experiment in rented facilities at his boarding house. Keeping "night owl" hours, he worried that his work would be discovered and took great pains to lock up his notebooks and laboratory equipment. Bell had a specially made table where he could place his notes and equipment inside a locking cover. His health deteriorated as he had severe headaches. Returning to Boston in autumn 1873, Bell made a far-reaching decision to concentrate on his experiments in sound.

Giving up his lucrative private Boston practice, Bell retained only two students, six-year-old "Georgie" Sanders, deaf from birth, and 15-year-old Mabel Hubbard. Each played an important role in the next developments. Georgie's father, Thomas Sanders, a wealthy businessman, offered Bell a place to stay in nearby Salem with Georgie's grandmother, complete with a room to "experiment". Although the offer was made by Georgie's mother and followed the year-long arrangement in 1872 where her son and his nurse had moved to quarters next to Bell's boarding house, it was clear that Mr. Sanders backed the proposal. The arrangement was for teacher and student to continue their work together, with free room and board thrown in. Mabel was a bright, attractive girl ten years Bell's junior who became the object of his affection. Having lost her hearing after a near-fatal bout of scarlet fever close to her fifth birthday, she had learned to read lips but her father, Gardiner Greene Hubbard, Bell's benefactor and personal friend, wanted her to work directly with her teacher.

The telephone

By 1874, Bell's initial work on the harmonic telegraph had entered a formative stage, with progress made both at his new Boston "laboratory" (a rented facility) and at his family home in Canada a big success. While working that summer in Brantford, Bell experimented with a " phonautograph", a pen-like machine that could draw shapes of sound waves on smoked glass by tracing their vibrations. Bell thought it might be possible to generate undulating electrical currents that corresponded to sound waves. He also thought that multiple metal reeds tuned to different frequencies like a harp would be able to convert the undulating currents back into sound. But he had no working model to demonstrate the feasibility of these ideas. In 1874, telegraph message traffic was rapidly expanding and, in the words of Western Union President William Orton, had become "the nervous system of commerce". Orton had contracted with inventorsThomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

and Elisha Gray

Elisha Gray (August 2, 1835 – January 21, 1901) was an American electrical engineering, electrical engineer who co-founded the Western Electric, Western Electric Manufacturing Company. Gray is best known for his Invention of the telephone, dev ...

to find a way to send multiple telegraph messages on each telegraph line to avoid the great cost of constructing new lines. When Bell mentioned to Gardiner Hubbard and Thomas Sanders that he was working on a method of sending multiple tones on a telegraph wire using a multi-reed device, the two began to financially support Bell's experiments. Patent matters were handled by Hubbard's patent attorney, Anthony Pollok.

In March 1875, Bell and Pollok visited the scientist Joseph Henry

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American physicist and inventor who served as the first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor ...

, then the director of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

, to ask his advice on the electrical multi-reed apparatus that Bell hoped would transmit the human voice by telegraph. Henry said Bell had "the germ of a great invention". When Bell said that he lacked the necessary knowledge, Henry replied, "Get it!" That declaration greatly encouraged Bell to keep trying, even though he had neither the equipment needed to continue his experiments nor the ability to create a working model of his ideas. But a chance meeting in 1874 between Bell and Thomas A. Watson, an experienced electrical designer and mechanic at the electrical machine shop of Charles Williams, changed that.

With financial support from Sanders and Hubbard, Bell hired Watson as his assistant, and the two experimented with acoustic telegraphy. On June 2, 1875, Watson accidentally plucked one of the reeds and Bell, at the receiving end of the wire, heard the reed's overtones that would be necessary for transmitting speech. That demonstrated to Bell that only one reed or armature was necessary, not multiple reeds. This led to the "gallows" sound-powered telephone, which could transmit indistinct, voice-like sounds, but not clear speech.

The race to the patent office

In 1875, Bell developed an acoustic telegraph and drew up a patent application for it. Since he had agreed to share U.S. profits with his investors Gardiner Hubbard and Thomas Sanders, Bell requested that an associate in Ontario, George Brown, attempt to patent it in Britain, instructing his lawyers to apply for a patent in the U.S. only after they received word from Britain (Britain issued patents only for discoveries not previously patented elsewhere). Meanwhile,Elisha Gray

Elisha Gray (August 2, 1835 – January 21, 1901) was an American electrical engineering, electrical engineer who co-founded the Western Electric, Western Electric Manufacturing Company. Gray is best known for his Invention of the telephone, dev ...

was also experimenting with acoustic telegraphy and thought of a way to transmit speech using a water transmitter. On February 14, 1876, Gray filed a caveat with the U.S. Patent Office for a telephone design that used a water transmitter. That same morning, Bell's lawyer filed Bell's application with the patent office. There is considerable debate about who arrived first and Gray later challenged the primacy of Bell's patent. Bell was in Boston on February 14 and did not arrive in Washington until February 26.

On March 7, 1876, the U.S. Patent Office issued Bell patent 174,465. It covered "the method of, and apparatus for, transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically ... by causing electrical undulations, similar in form to the vibrations of the air accompanying the said vocal or other sound" Bell returned to Boston that day and the next day resumed work, drawing in his notebook a diagram similar to that in Gray's patent caveat.

On March 10, Bell succeeded in getting his telephone to work, using a liquid transmitter similar to Gray's design. Vibration of the diaphragm caused a needle to vibrate in the water, varying the electrical resistance

The electrical resistance of an object is a measure of its opposition to the flow of electric current. Its reciprocal quantity is , measuring the ease with which an electric current passes. Electrical resistance shares some conceptual paral ...

in the circuit. When Bell spoke the sentence "Mr. Watson—Come here—I want to see you" into the liquid transmitter, Watson, listening at the receiving end in an adjoining room, heard the words clearly.

Although Bell was, and still is, accused of stealing the telephone from Gray, Bell used Gray's water transmitter design only after Bell's patent had been granted, and only as a proof of concept scientific experiment, to prove to his own satisfaction that intelligible "articulate speech" (Bell's words) could be electrically transmitted. After March 1876, Bell focused on improving the electromagnetic telephone and never used Gray's liquid transmitter in public demonstrations or commercial use.

The examiner raised the question of priority for the variable resistance feature of the telephone before approving Bell's patent application. He told Bell that his claim for the variable resistance feature was also described in Gray's caveat. Bell pointed to a variable resistance device in his previous application in which he described a cup of mercury, not water. He had filed the mercury application at the patent office on February 25, 1875, long before Gray described the water device. In addition, Gray abandoned his caveat, and because he did not contest Bell's priority, the examiner approved Bell's patent on March 3, 1876. Gray had reinvented the variable resistance telephone, but Bell was the first to write down the idea and test it in a telephone.

The patent examiner

A patent examiner (or, historically, a patent clerk) is an employee, usually a civil service, civil servant with a scientific or engineering background, working at a patent office.

Duties

Due to a long-standing and incessantly growing backlog of u ...

, Zenas Fisk Wilber, later stated in an affidavit that he was an alcoholic who was much in debt to Bell's lawyer, Marcellus Bailey, with whom he had served in the Civil War. He said he had shown Bailey Gray's patent caveat. Wilber also said (after Bell arrived in Washington D.C. from Boston) that he showed Bell Gray's caveat and that Bell paid him $100 (). Bell said they discussed the patent only in general terms, although in a letter to Gray, Bell admitted that he learned some of the technical details. Bell denied in an affidavit that he ever gave Wilber any money.

Later developments

On March 10, 1876, Bell used "the instrument" in Boston to call Thomas Watson who was in another room but out of earshot. He said, "Mr. Watson, come here – I want to see you" and Watson soon appeared at his side. Continuing his experiments in Brantford, Bell brought home a working model of his telephone. On August 3, 1876, from the telegraph office in Brantford, Bell sent a telegram to the village of Mount Pleasant away, indicating that he was ready. He made a telephone call via telegraph wires and faint voices were heard replying. The following night, he amazed guests as well as his family with a call between the Bell Homestead and the office of the Dominion Telegraph Company in Brantford along an improvised wire strung up along telegraph lines and fences, and laid through a tunnel. This time, guests at the household distinctly heard people in Brantford reading and singing. The third test, on August 10, 1876, was made via the telegraph line between Brantford and Paris, Ontario, away. This test is said by many sources to be the "world's first long-distance call". It proved that the telephone could work over long distances, at least as a one-way call. The first two-way (reciprocal) conversation over a line occurred between Cambridge and Boston (roughly 2.5 miles) on October 9, 1876. During that conversation, Bell was on Kilby Street in Boston and Watson was at the offices of the Walworth Manufacturing Company. Bell and his partners, Hubbard and Sanders, offered to sell the patent outright to Western Union for $100,000, equal to $ today, but it did not work (according to an apocryphal story, the president of Western Union balked, countering that the telephone was nothing but a toy). Two years later, he told colleagues that if he could get the patent for $25 million (equal to $ today), he would consider it a bargain. By then, the Bell company no longer wanted to sell the patent. Bell's investors became millionaires while he fared well from residuals and at one point had assets of nearly $1 million.

Bell began a series of public demonstrations and lectures to introduce the new invention to the scientific community as well as the general public. A short time later, his demonstration of an early telephone prototype at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in

Bell and his partners, Hubbard and Sanders, offered to sell the patent outright to Western Union for $100,000, equal to $ today, but it did not work (according to an apocryphal story, the president of Western Union balked, countering that the telephone was nothing but a toy). Two years later, he told colleagues that if he could get the patent for $25 million (equal to $ today), he would consider it a bargain. By then, the Bell company no longer wanted to sell the patent. Bell's investors became millionaires while he fared well from residuals and at one point had assets of nearly $1 million.

Bell began a series of public demonstrations and lectures to introduce the new invention to the scientific community as well as the general public. A short time later, his demonstration of an early telephone prototype at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

brought the telephone to international attention. Influential visitors to the exhibition included Emperor Pedro II of Brazil

''Don (honorific), Dom'' PedroII (Pedro de Alcântara João Carlos Leopoldo Salvador Bibiano Francisco Xavier de Paula Leocádio Miguel Gabriel Rafael Gonzaga; 2 December 1825 – 5 December 1891), nicknamed the Magnanimous (), was the List o ...

. One of the judges at the Exhibition, Sir William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin), a renowned Scottish scientist, described the telephone as "the greatest by far of all the marvels of the electric telegraph".

On January 14, 1878, at Osborne House, on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

, Bell demonstrated the device to Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

, placing calls to Cowes, Southampton, and London. These were the first publicly witnessed long-distance telephone calls in the UK. The queen found the process "quite extraordinary" although the sound was "rather faint". She later asked to buy the equipment that was used, but Bell offered to make "a set of telephones" specifically for her.

The Bell Telephone Company was created in 1877, and by 1886, more than 150,000 people in the U.S. owned telephones. Bell Company engineers made numerous other improvements to the telephone, which emerged as one of the most successful products ever. In 1879, the company acquired Edison's patents for the carbon microphone from Western Union. This made the telephone practical for longer distances, and it was no longer necessary to shout to be heard at the receiving telephone.

Pedro II of Brazil was the first person to buy stock in the Bell Telephone Company. One of the first telephones in a private residence was installed in his palace in Petrópolis, his summer retreat from Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-most-populous city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and the Largest cities in the America ...

.

In January 1915, Bell made the first ceremonial transcontinental telephone call

A telephone call, phone call, voice call, or simply a call, is the effective use of a connection over a telephone network between the calling party and the called party.

Telephone calls are the form of human communication that was first enabl ...

. Calling from the AT&T head office at 15 Dey Street in New York City, Bell was heard by Thomas Watson at 333 Grant Avenue in San Francisco. ''The New York Times'' reported:

Competitors

As is sometimes common in scientific discoveries, simultaneous developments occurred, as evidenced by a number of inventors who were at work on the telephone. Over 18 years, the Bell Telephone Company faced 587 court challenges to its patents, including five that went to the U.S. Supreme Court, but none was successful in establishing priority over Bell's original patent, and the Bell Telephone Company never lost a case that had proceeded to a final trial stage. Bell's laboratory notes and family letters were the key to establishing a long lineage to his experiments. The Bell company lawyers successfully fought off myriad lawsuits generated initially around the challenges by Elisha Gray and Amos Dolbear. In personal correspondence to Bell, both Gray and Dolbear had acknowledged his prior work, which considerably weakened their later claims. On January 13, 1887, the U.S. government moved to annul the patent issued to Bell on the grounds of fraud and misrepresentation. After a series of decisions and reversals, the Bell company won a decision in the Supreme Court, though a couple of the original claims from the lower court cases were left undecided. By the time the trial had wound its way through nine years of legal battles, the U.S. prosecuting attorney had died and the two Bell patents (No. 174,465, dated March 7, 1876, and No. 186,787, dated January 30, 1877) were no longer in effect, although the presiding judges agreed to continue the proceedings due to the case's importance as aprecedent

Precedent is a judicial decision that serves as an authority for courts when deciding subsequent identical or similar cases. Fundamental to common law legal systems, precedent operates under the principle of ''stare decisis'' ("to stand by thin ...

. With a change in administration and charges of conflict of interest (on both sides) arising from the original trial, the U.S. attorney general dropped the lawsuit on November 30, 1897, leaving several issues undecided on the merits.

During a deposition filed for the 1887 trial, Italian inventor Antonio Meucci also claimed to have created the first working model of a telephone in Italy in 1834. In 1886, in the first of three cases in which he was involved, Meucci took the stand as a witness in hope of establishing his invention's priority. Meucci's testimony was disputed due to lack of material evidence for his inventions, as his working models were purportedly lost at the laboratory of American District Telegraph (ADT) of New York, which was incorporated as a subsidiary of Western Union in 1901. Meucci's work, like that of many other inventors of the period, was based on earlier acoustic principles and, despite evidence of earlier experiments, the final case involving Meucci was eventually dropped upon Meucci's death. But due to the efforts of Congressman Vito Fossella, on June 11, 2002, the U.S. House of Representatives stated that Meucci's "work in the invention of the telephone should be acknowledged". This did not put an end to the still contentious issue. Some modern scholars do not agree that Bell's work on the telephone was influenced by Meucci's inventions.

The value of Bell's patent was acknowledged throughout the world, and patent applications were made in most major countries. When Bell delayed the German patent application, the electrical firm Siemens & Halske set up a rival manufacturer of Bell telephones under its own patent. Siemens produced near-identical copies of the Bell telephone without having to pay royalties. The establishment of the International Bell Telephone Company in Brussels, Belgium, in 1880, as well as a series of agreements in other countries eventually consolidated a global telephone operation. The strain put on Bell by his constant appearances in court, necessitated by the legal battles, eventually resulted in his resignation from the company.

Family life

On July 11, 1877, a few days after the Bell Telephone Company was established, Bell married Mabel Hubbard (1857–1923) at the Hubbard estate in

On July 11, 1877, a few days after the Bell Telephone Company was established, Bell married Mabel Hubbard (1857–1923) at the Hubbard estate in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is a suburb in the Greater Boston metropolitan area, located directly across the Charles River from Boston. The city's population as of the 2020 United States census, ...

. His wedding present to his bride was to turn over 1,487 of his 1,497 shares in the newly formed Bell Telephone Company. Shortly thereafter, the newly-weds embarked on a year-long honeymoon in Europe. During that excursion, Bell took a handmade model of his telephone with him, making it a "working holiday". The courtship had begun years earlier; however, Bell waited until he was more financially secure before marrying. Although the telephone appeared to be an "instant" success, it was not initially a profitable venture and Bell's main sources of income were from lectures until after 1897. One unusual request exacted by his fiancée was that he use "Alec" rather than the family's earlier familiar name of "Aleck". From 1876, he would sign his name "Alec Bell". They had four children:

* Elsie May Bell (1878–1964) who married Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor of National Geographic fame.

* Marian Hubbard Bell (1880–1962) who was referred to as "Daisy". Married David Fairchild.

* Two sons who died in infancy (Edward in 1881 and Robert in 1883).

The Bell family home was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, until 1880 when Bell's father-in-law bought a house in Washington, D.C.; in 1882 he bought a home in the same city for Bell's family, so they could be with him while he attended to the numerous court cases involving patent disputes.

Bell was a British subject throughout his early life in Scotland and later in Canada until 1882 when he became a naturalized citizen of the United States. In 1915, he characterized his status as: "I am not one of those hyphenated Americans who claim allegiance to two countries." Despite this declaration, Bell has been proudly claimed as a "native son" by all three countries he resided in: the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom.

By 1885, a new summer retreat was contemplated. That summer, the Bells had a vacation on Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (, formerly '; or '; ) is a rugged and irregularly shaped island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18.7% of Nova Scotia's total area. Although ...

in Nova Scotia, Canada, spending time at the small village of Baddeck. Returning in 1886, Bell started building an estate on a point across from Baddeck, overlooking Bras d'Or Lake. By 1889, a large house, christened ''The Lodge'' was completed and two years later, a larger complex of buildings, including a new laboratory, were begun that the Bells would name Beinn Bhreagh ( Gaelic: ''Beautiful Mountain'') after Bell's ancestral Scottish highlands

The Highlands (; , ) is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Scottish Lowlands, Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Scots language, Lowland Scots language replaced Scottish Gae ...

. Bell also built the Bell Boatyard on the estate, employing up to 40 people building experimental craft as well as wartime lifeboats and workboats for the Royal Canadian Navy

The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN; , ''MRC'') is the Navy, naval force of Canada. The navy is one of three environmental commands within the Canadian Armed Forces. As of February 2024, the RCN operates 12 s, 12 s, 4 s, 4 s, 8 s, and several auxiliary ...

and pleasure craft for the Bell family. He was an enthusiastic boater, and Bell and his family sailed or rowed a long series of vessels on Bras d'Or Lake, ordering additional vessels from the H.W. Embree and Sons boatyard in Port Hawkesbury, Nova Scotia. In his final, and some of his most productive years, Bell split his residency between Washington, D.C., where he and his family initially resided for most of the year, and Beinn Bhreagh, where they spent increasing amounts of time.

Until the end of his life, Bell and his family would alternate between the two homes, but ''Beinn Bhreagh'' would, over the next 30 years, become more than a summer home as Bell became so absorbed in his experiments that his annual stays lengthened. Both Mabel and Bell became immersed in the Baddeck community and were accepted by the villagers as "their own". The Bells were still in residence at ''Beinn Bhreagh'' when the Halifax Explosion occurred on December 6, 1917. Mabel and Bell mobilized the community to help victims in Halifax.

Later inventions

Although Alexander Graham Bell is most often associated with the invention of the telephone, his interests were extremely varied. According to one of his biographers, Charlotte Gray, Bell's work ranged "unfettered across the scientific landscape" and he often went to bed voraciously reading the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', scouring it for new areas of interest. The range of Bell's inventive genius is represented only in part by the 18 patents granted in his name alone and the 12 he shared with his collaborators. These included 14 for the telephone and telegraph, four for the photophone, one for the phonograph, five for aerial vehicles, four for "hydroairplanes", and two for

Although Alexander Graham Bell is most often associated with the invention of the telephone, his interests were extremely varied. According to one of his biographers, Charlotte Gray, Bell's work ranged "unfettered across the scientific landscape" and he often went to bed voraciously reading the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', scouring it for new areas of interest. The range of Bell's inventive genius is represented only in part by the 18 patents granted in his name alone and the 12 he shared with his collaborators. These included 14 for the telephone and telegraph, four for the photophone, one for the phonograph, five for aerial vehicles, four for "hydroairplanes", and two for selenium

Selenium is a chemical element; it has symbol (chemistry), symbol Se and atomic number 34. It has various physical appearances, including a brick-red powder, a vitreous black solid, and a grey metallic-looking form. It seldom occurs in this elem ...

cells. Bell's inventions spanned a wide range of interests and included a metal jacket to assist in breathing, the audiometer to detect minor hearing problems, a device to locate icebergs, investigations on how to separate salt from seawater, and work on finding alternative fuel

Alternative fuels, also known as non-conventional and advanced fuels, are fuels derived from sources other than petroleum. Alternative fuels include gaseous fossil fuels like propane, natural gas, methane, and ammonia; biofuels like biodies ...

s.

Bell worked extensively in medical research

Medical research (or biomedical research), also known as health research, refers to the process of using scientific methods with the aim to produce knowledge about human diseases, the prevention and treatment of illness, and the promotion of ...

and invented techniques for teaching speech to the deaf. During his Volta Laboratory period, Bell and his associates considered impressing a magnetic field

A magnetic field (sometimes called B-field) is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular ...

on a record as a means of reproducing sound. Although the trio briefly experimented with the concept, they could not develop a workable prototype. They abandoned the idea, never realizing they had glimpsed a basic principle which would one day find its application in the tape recorder

An audio tape recorder, also known as a tape deck, tape player or tape machine or simply a tape recorder, is a sound recording and reproduction device that records and plays back sounds usually using magnetic tape for storage. In its present ...

, the hard disc and floppy disc drive, and other magnetic media.

Bell's own home used a primitive form of air conditioning, in which fans blew currents of air across great blocks of ice. He also anticipated modern concerns with fuel shortages and industrial pollution. Methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The abundance of methane on Earth makes ...

gas, he reasoned, could be produced from the waste of farms and factories. At his Canadian estate in Nova Scotia, he experimented with composting toilets and devices to capture water from the atmosphere. In a magazine article published in 1917, he reflected on the possibility of using solar energy

Solar energy is the radiant energy from the Sun's sunlight, light and heat, which can be harnessed using a range of technologies such as solar electricity, solar thermal energy (including solar water heating) and solar architecture. It is a ...

to heat houses.

Photophone

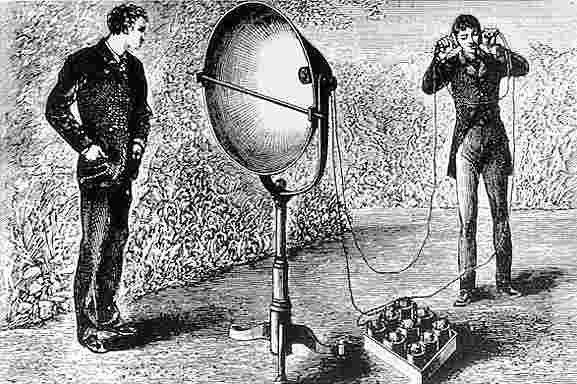

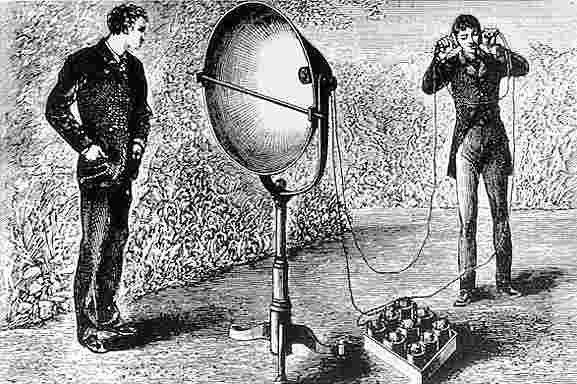

Bell and his assistant

Bell and his assistant Charles Sumner Tainter

Charles Sumner Tainter (April 25, 1854 – April 20, 1940) was an American scientific instrument maker, engineer and inventor, best known for his collaborations with Alexander Graham Bell, Chichester Bell, Alexander's father-in-law Gardiner Hubba ...

jointly invented a wireless telephone, named a photophone, which allowed for the transmission of both sounds and normal human conversations on a beam of light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

. Both men later became full associates in the Volta Laboratory Association.

On June 21, 1880, Bell's assistant transmitted a wireless voice telephone message a considerable distance, from the roof of the Franklin School in Washington, D.C., to Bell at the window of his laboratory, some away, 19 years before the first voice radio transmissions.

Bell believed the photophone's principles were his life's "greatest achievement", telling a reporter shortly before his death that the photophone was "the greatest invention haveever made, greater than the telephone". The photophone was a precursor to the fiber-optic communication

Fiber-optic communication is a form of optical communication for transmitting information from one place to another by sending pulses of infrared or visible light through an optical fiber. The light is a form of carrier wave that is modul ...

systems which achieved popular worldwide usage in the 1980s. Its master patent was issued in December 1880, many decades before the photophone's principles came into popular use.

Metal detector

Bell is also credited with developing one of the early versions of a metal detector through the use of an induction balance, after the shooting of U.S. President James A. Garfield in 1881. According to some accounts, the metal detector worked flawlessly in tests but did not find Guiteau's bullet, partly because the metal bed frame on which the President was lying disturbed the instrument, resulting in static. Garfield's surgeons, led by self-appointed chief physician Doctor Willard Bliss, were sceptical of the device, and ignored Bell's requests to move the President to a bed not fitted with metal springs. Alternatively, although Bell had detected a slight sound on his first test, the bullet may have been lodged too deeply to be detected by the crude apparatus. Bell's own detailed account, presented to theAmerican Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is a United States–based international nonprofit with the stated mission of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsib ...

in 1882, differs in several particulars from most of the many and varied versions now in circulation, by concluding that extraneous metal was not to blame for failure to locate the bullet. Perplexed by the peculiar results he had obtained during an examination of Garfield, Bell "proceeded to the Executive Mansion the next morning ... to ascertain from the surgeons whether they were perfectly sure that all metal had been removed from the neighborhood of the bed. It was then recollected that underneath the horse-hair mattress on which the President lay was another mattress composed of steel wires. Upon obtaining a duplicate, the mattress was found to consist of a sort of net of woven steel wires, with large meshes. The extent of the rea that produced a response from the detectorhaving been so small, as compared with the area of the bed, it seemed reasonable to conclude that the steel mattress had produced no detrimental effect." In a footnote, Bell adds, "The death of President Garfield and the subsequent ''post-mortem'' examination, however, proved that the bullet was at too great a distance from the surface to have affected our apparatus."

Hydrofoils

The March 1906 ''

The March 1906 ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it, with more than 150 Nobel Pri ...

'' article by American pioneer William E. Meacham explained the basic principle of hydrofoils and hydroplanes. Bell considered the invention of the hydroplane as a very significant achievement. Based on information gained from that article, he began to sketch concepts of what is now called a hydrofoil boat. Bell and assistant Frederick W. "Casey" Baldwin began hydrofoil experimentation in the summer of 1908 as a possible aid to airplane takeoff from water. Baldwin studied the work of the Italian inventor Enrico Forlanini and began testing models. This led him and Bell to the development of practical hydrofoil watercraft.

During his world tour of 1910–11, Bell and Baldwin met with Forlanini in France. They had rides in the Forlanini hydrofoil boat over Lake Maggiore. Baldwin described it as being as smooth as flying. On returning to Baddeck, a number of initial concepts were built as experimental models, including the ''Dhonnas Beag'' (Scottish Gaelic for 'little devil'), the first self-propelled Bell-Baldwin hydrofoil. The experimental boats were essentially proof-of-concept prototypes that culminated in the more substantial HD-4

''HD-4'' or ''Hydrodome number 4'' was an early research hydrofoil watercraft developed by the scientist Alexander Graham Bell. It was designed and built at the Bell Boatyard on Bell's Beinn Bhreagh estate near Baddeck, Nova Scotia. In 191 ...

, powered by Renault

Renault S.A., commonly referred to as Groupe Renault ( , , , also known as the Renault Group in English), is a French Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automobile manufacturer established in 1899. The company curr ...

engines. A top speed of was achieved, with the hydrofoil exhibiting rapid acceleration, good stability, and steering, along with the ability to take waves without difficulty.

In 1913, Dr. Bell hired Walter Pinaud, a Sydney yacht designer and builder as well as the proprietor of Pinaud's Yacht Yard in Westmount, Nova Scotia, to work on the pontoons of the HD-4. Pinaud soon took over the boatyard at Bell Laboratories on Beinn Bhreagh, Bell's estate near Baddeck, Nova Scotia. Pinaud's experience in boatbuilding enabled him to make useful design changes to the HD-4. After the First World War, work began again on the HD-4. Bell's report to the U.S. Navy permitted him to obtain two engines in July 1919. On September 9, 1919, the HD-4 set a world marine speed record of , a record which stood for ten years.

Aeronautics

In 1891, Bell had begun experiments to develop motor-powered heavier-than-air aircraft. The AEA was first formed as Bell shared the vision to fly with his wife, who advised him to seek "young" help as Bell was at the age of 60.

In 1898, Bell experimented with tetrahedral box kites and wings constructed of multiple compound tetrahedral kites covered in maroon silk. The tetrahedral wings were named ''Cygnet'' I, II, and III, and were flown both unmanned and manned (''Cygnet I'' crashed during a flight carrying Selfridge) in the period from 1907 to 1912. Some of Bell's kites are on display at the Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site.