Alden Brooks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alden Brooks (1882–1964) was an American writer, chiefly remembered for his proposal that Sir Edward Dyer wrote the works of

World War I broke out while Brooks was in France, and he became an ambulance driver and subsequently a newspaper correspondent for ''

World War I broke out while Brooks was in France, and he became an ambulance driver and subsequently a newspaper correspondent for ''

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

.

Early life

Brooks was in born in 1882 inCleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

, Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

. He attended schools in France and England, before graduating from Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

in 1905.

Career

Brooks taught at Harvard and as an instructor at theU.S. Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy is the sec ...

. He subsequently became for a time a tobacco farmer in southern Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

, until he moved to France.

World War I

World War I broke out while Brooks was in France, and he became an ambulance driver and subsequently a newspaper correspondent for ''

World War I broke out while Brooks was in France, and he became an ambulance driver and subsequently a newspaper correspondent for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

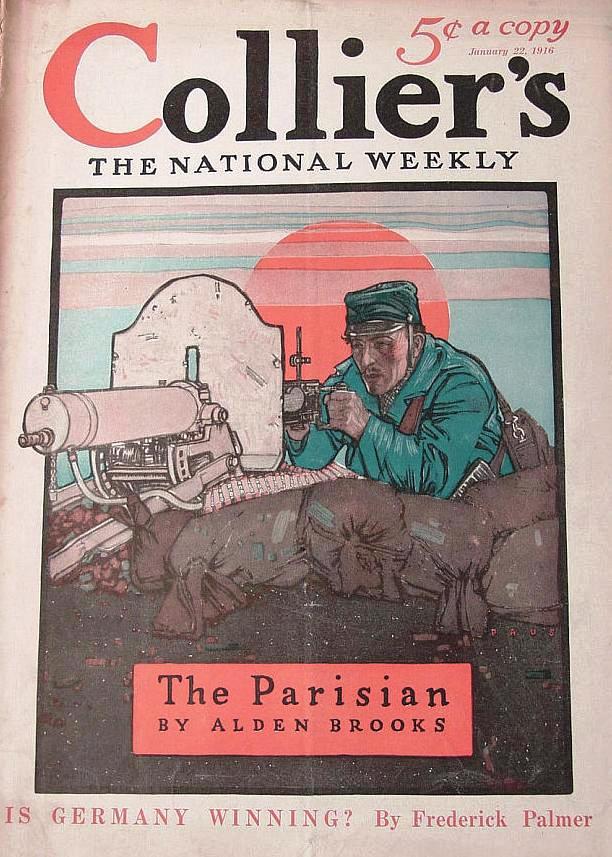

'' and ''Collier's

}

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter F. Collier, Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened i ...

''. He eventually took up duty as an ambulance driver for American troops on the front line. He was eager to join the A.E.F and thought the quickest way would be to study in a French artillery school. He served with the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

and rose to the rank of lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

of a field battery, after his petition for transfer to the American forces was turned down on the grounds of poor eyesight. He saw action at Marne, Chemin-des-Dames, Chateau-Thierry and Meuse-Argonne, and was awarded the ''Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

'' with a silver star for gallantry while engaged in special missions in France on July 15 and 16, 1918. He deplored much of what he saw, including how General Robert Lee Bullard sent American troops to fight and die even though the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

was due to be declared in a few hours, and wrote of war's folly:

War is stupid, insensate, unheroic to the last degree. War is not waged like a game. Analogies of the football field and of the chessboard are completely erroneous. War is a brutal chaos, governed by no laws.Brooks published his first book, ''The Fighting Men'', in 1917. It consisted of a series of six short sketches depicting the respective psychological and behavioral traits of an

ethnic group

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

of soldiers, respectively English, Slav

The Slavs or Slavic people are groups of people who speak Slavic languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout the northern parts of Eurasia; they predominantly inhabit Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and N ...

, American, French, Belgian and Prussian.

Brooks lived for a long period in France, and his home in Paris, ''Maison Brooks'' built at 80 boulevard Arago in 1929, was designed by the architect Paul Nelson. His experiences of the war are recounted in his 1929 book ''Battle in 1918, As Seen by an American in the French Army'', published in the United States as ''As I Saw It''.

Shakespeare authorship theories

Aside from a novel, ''Escape'' (1924), Brooks wrote extensively on the Shakespeare authorship question, and in 1937 produced a preliminary volume, ''Will Shakspere: Factotum and Agent'', in an attempt to prove that Shakespeare did not write the works attributed to him. In this book, Shakespeare is considered to be a pseudonym, and thesonnets

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

are attributed to Thomas Nashe

Thomas Nashe (also Nash; baptised 30 November 1567 – c. 1601) was an English Elizabethan playwright, poet, satirist and a significant pamphleteer. He is known for his novel '' The Unfortunate Traveller'', his pamphlets including '' Pierce P ...

, Samuel Daniel

Samuel Daniel (1562–1619) was an English poet, playwright and historian in the late-Elizabethan and early- Jacobean eras. He was an innovator in a wide range of literary genres. His best-known works are the sonnet cycle ''Delia'', the epic ...

, Barnabe Barnes and some other editorial hand. A contemporary scholar reviewing Brooks's ideas commented that although "there is absolutely no evidence to support any of his statements his

His or HIS may refer to:

Computing

* Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company

* Honeywell Information Systems

* Hybrid intelligent system

* Microsoft Host Integration Server

Education

* Hangzhou International School, ...

disturbed neither Brooks nor his publishers."

Six years later, he fulfilled his earlier promise of identifying the supposed real author by publishing ''Will Shakspere and the Dyer's Hand'' (1943) declaring that Sir Edward Dyer was the true author. His methodology consisted of specifying 54 criteria or qualifications which worked to the exclusion of the many false claimants the establishment of the true author's identity, only all of which his candidate, Sir Edward Dyer, was thought to meet in "concordance with the pattern". The book, in the ironical words of one historian of the phenomenon, "did not ignite a crusade".

William Shakespeare was, in Brooks' imaginative reconstruction, little more than a "fool, knave, usurer, vulgar showman, illiterate, bluffer, philander, pander, and brothel keeper" who however acted at the same time as the literary agent of Dyer, the concealed author. An anonymous reviewer for ''Time'' magazine summed up the plot in the following way:

He depicts Shakespeare as a butcher's son in Stratford, "a country youth who has to leave school early in order to assist his father in the killing of cattle ... one who sows his wild oats so liberally that he must, first, marry against his will a woman eight years his senior, and, secondly, run away to London, apparently to escape legal prosecution." ... in London he got a job holding theatergoers' horses. Soon he earned enough money to rent out theatrical costumes and furnishings. Something of a wit in his coarse way, he began editing plays for production, soon became a play agent, buying and renting the works of others. On the side he kept a brothel: "In his tavern in Deadman's Lane, sub-leased to Widow Lee, Will Shakspere ... created ... a roistering hubbub." His "broken, almost falsetto voice" became a feature of London life. His "fat body" was soon "taxed by excesses." Many suffered from "his scheming tricks ... his dirty dealing and underhand passing of coin, all the shabby pretense in the double-faced glutton and roisterer." Meanwhile a grey-haired courtier with "wrinkled visage, deep-set eyes ... walked nervously in the gardens" a stone's throw from Will's brothel. The courtier's name was Sir Edward Dyer, known to literati mainly as the author of a rather smug poem called My Mind to Me a Kingdom Is. No one guessed his secret, but for years, says Author Brooks, Dyer had been getting Shakespeare to buy bad plays for him and had rewritten them into the classics we read today.He overcame the problem that Dyer died in 1607, several years before Shakespeare's ''

The Tempest

''The Tempest'' is a Shakespeare's plays, play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1610–1611, and thought to be one of the last plays that he wrote alone. After the first scene, which takes place on a ship at sea during a tempest, th ...

'' is believed to have been written, by arguing that this was early work, which he believed was proven by its appearance as the first play in the 1623 Folio edition of Shakespeare's plays.

Personal life, death and legacy

Brooks married Hilma Chadwick, an artist, atSt Ives, Cornwall

St Ives (, meaning "Ia of Cornwall, St Ia's cove") is a seaside town, civil parish and port in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The town lies north of Penzance and west of Camborne on the coast of the Celtic Sea. In former times, it was comm ...

, England, on 11 July 1908, and moved to France. They had four children.

Brooks died in 1964.

Brook's vivid depictions of soldiers and war have been highly praised by specialists. Phillip K. Jason argues that he wrote "two of the most intriguing books about World War 1." His researches attempting to reveal Sir Edward Dyer behind Shakespeare have usually been dismissed as fantasies. William M. Murphy writes:

To a man who can tell us so much about Shakespeare on no visible evidence, no flight of illogical fancy is impossible.He has, however, decisively influenced one recent independent researcher into the authorship heterodoxy. Diana Price, in her book ''Shakespeare's Unorthodox Biography'' (2001) writes on her acknowledgements page of "the ground-breaking research of Alden Brooks".

Bibliography

* ''Escape'', Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1924 * ''As I Saw It'', Knopf, New York, 1930 * ''Will Shakspere: Factotum and Agent'', 1937 * ''Will Shakspere and the Dyer's Hand'', 1943Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Brooks, Alden 1882 births 1964 deaths American expatriates in France Writers from Cleveland Writers from Paris American male writers Shakespeare authorship theorists Harvard University alumni French Army officers French military personnel of World War I English male dramatists and playwrights