Albert Piddington on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

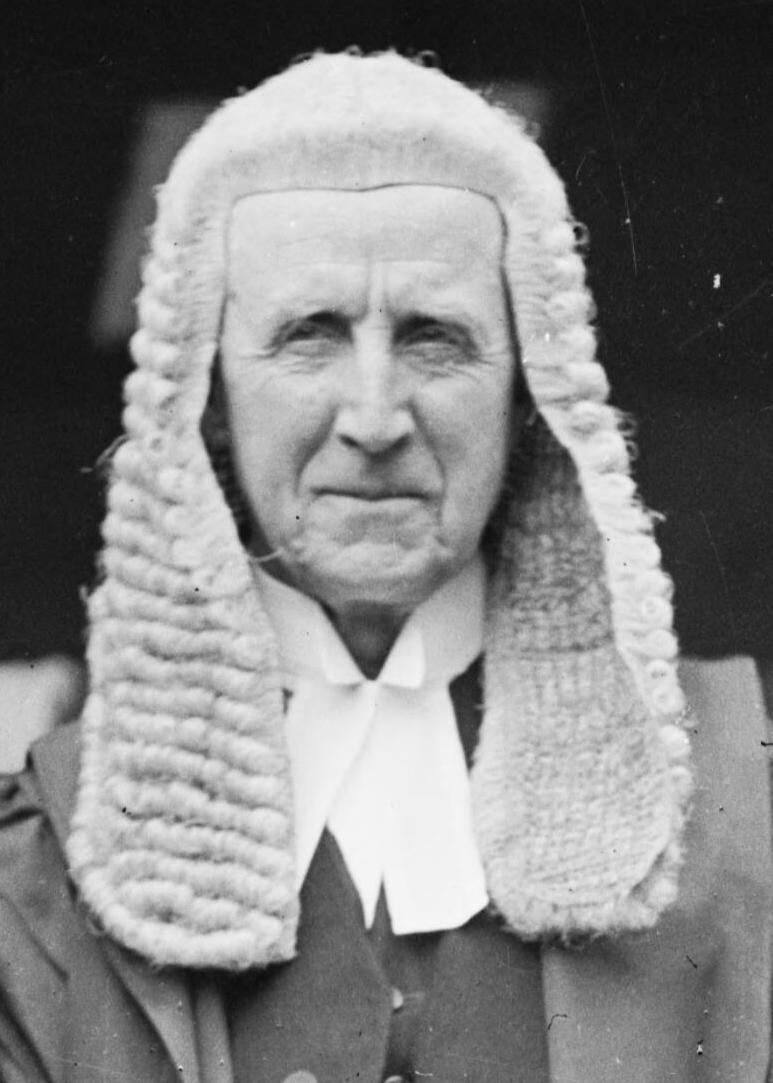

Albert Bathurst Piddington KC (9 September 1862 – 5 June 1945) was an Australian lawyer, politician and judge. He was a member of the

Piddington first stood for parliament at the 1894 New South Wales general election, running on a radical platform against incumbent premier

Piddington first stood for parliament at the 1894 New South Wales general election, running on a radical platform against incumbent premier

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the apex court of the Australian legal system. It exercises original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified in the Constitution of Australia and supplementary legislation.

The High Court was establi ...

for one month in 1913, making him the shortest-serving judge in the court's history.

Piddington was born in Bathurst, New South Wales

Bathurst () is a city in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia. Bathurst is about 200 kilometres (120 mi) west-northwest of Sydney and is the seat of the Bathurst Region, Bathurst Regional Council. Founded in 1815, Bathurst is ...

. He studied classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

at the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD) is a public university, public research university in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in both Australia and Oceania. One of Australia's six sandstone universities, it was one of the ...

, and later combined his legal studies with teaching at Sydney Boys High School. Piddington was elected to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

The New South Wales Legislative Assembly is the lower of the two houses of the Parliament of New South Wales, an Australian state. The upper house is the New South Wales Legislative Council. Both the Assembly and Council sit at Parliament House ...

in 1895, representing the Free Trade Party

The Free Trade Party (FTP), officially known as the Free Trade and Liberal Association and also referred to as the Revenue Tariff Party in some states, was an Australian political party. It was formally organised in 1887 in New South Wales, in ...

. He was defeated after a single term, and subsequently returned to his legal practice, becoming one of Sydney's best-known barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

s. Piddington was sympathetic to the labour movement, and in April 1913 Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher (29 August 186222 October 1928) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the fifth prime minister of Australia from 1908 to 1909, 1910 to 1913 and 1914 to 1915. He held office as the leader of the Australian ...

nominated him to the High Court as part of a court-packing attempt. His appointment was severely criticised, and he resigned a month later without ever sitting on the bench. Later in 1913, Piddington was made the inaugural chairman of the Inter-State Commission

The Inter-State Commission, or Interstate Commission, is a defunct Constitution of Australia, constitutional body under Australian law. The envisaged chief functions of the Inter-State Commission were to administer and adjudicate matters relati ...

, serving until 1920. He was appointed King's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

in 1913, and remained a public figure into his seventies.

Early life

Piddington was born on 9 September 1862 inBathurst, New South Wales

Bathurst () is a city in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia. Bathurst is about 200 kilometres (120 mi) west-northwest of Sydney and is the seat of the Bathurst Region, Bathurst Regional Council. Founded in 1815, Bathurst is ...

. He was the third son born to Annie (née Burgess) and William Jones Killick Piddington. His father was born in England and arrived in the colony of Tasmania

The Colony of Tasmania (more commonly referred to simply as "Tasmania") was a British colony that existed on the island of Tasmania from 1856 until 1901, when it federated together with the five other Australian colonies to form the Commonweal ...

as a young man, where he was a Methodist lay preacher

A lay preacher is a preacher who is not ordained (i.e. a layperson) and who may not hold a formal university degree in theology. Lay preaching varies in importance between religions and their sects.

Overview

Some denominations specifically disco ...

. His mother was born in Tasmania.

Piddington spent his early years in inner Sydney where his father was active in Methodist missionary work. His father eventually joined the Church of England and served as an ordained minister in various towns in country New South Wales, ending his career as an archdeacon

An archdeacon is a senior clergy position in the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, St Thomas Christians, Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox churches and some other Christian denomina ...

at Tamworth. Piddington completed his secondary education at Sydney Grammar School

Sydney Grammar School (SGS, colloquially known as Grammar) is an independent, non-denominational day school for boys, located in Sydney, Australia.

Incorporated in 1854 by an Act of Parliament and opened in 1857, the school claims to offer "c ...

. He went on to attend the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD) is a public university, public research university in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in both Australia and Oceania. One of Australia's six sandstone universities, it was one of the ...

, graduating Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

in 1883 and winning the university medal

A University Medal is one of several types of award conferred by university, universities upon outstanding students or members of staff. The usage and status of university medals differ between countries and between universities.

As award on grad ...

in classics.

After graduating from university, Piddington taught Latin and Greek for a period at the newly created Sydney High School. He subsequently read for the bar and was admitted as a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

in 1890, serving as a judge's associate

A judge's associate is an individual who provides assistance to a judge or court.

In Australia, a judge's associate (not to be confused with a tipstaff) is a recent law graduate or lawyer who performs various duties to assist a specific judge, s ...

under William Windeyer for a period. Piddington joined the University of Sydney's faculty in 1889 as a lecturer in English literature. In 1892 he published ''Sir Roger de Coverley'', a collection of 18th-century essays from ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British political and cultural news magazine. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving magazine in the world. ''The Spectator'' is politically conservative, and its principal subject a ...

''. The following year he edited a new edition of the fifth and sixth books of John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, and civil servant. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'' was written in blank verse and included 12 books, written in a time of immense religious flux and politic ...

's ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an Epic poetry, epic poem in blank verse by the English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The poem concerns the Bible, biblical story of the fall of man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their ex ...

'', which he titled ''The Fall of Satan''. His edition included a discussion of the historical background of Milton's work in the context of Puritanism

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should ...

.

Political career

Piddington first stood for parliament at the 1894 New South Wales general election, running on a radical platform against incumbent premier

Piddington first stood for parliament at the 1894 New South Wales general election, running on a radical platform against incumbent premier George Dibbs

Sir George Richard Dibbs KCMG (12 October 1834 – 5 August 1904) was an Australian politician who was Premier of New South Wales on three occasions.

Early years

Dibbs was born in Sydney, son of Captain John Dibbs, who 'disappeared' in the ...

. He resigned his lectureship at the University of Sydney to contest the election, following the university senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

's decision that it would decline to grant him leave; it was rumoured that Dibbs had pressured the senate to do so. Piddington was defeated by Dibbs at the election in the Legislative Assembly seat of Tamworth, although Dibbs lost his majority in the assembly and was replaced as premier by George Reid

Sir George Houston Reid (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was a Scottish-born Australian and British politician, diplomat, and barrister who served as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia, prime minister of Australia from 1904 t ...

, leading an alliance of the Free Trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

and Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

groups.

In 1895, Reid called an early election following obstruction of his legislative agenda by conservatives in the Legislative Council

A legislative council is the legislature, or one of the legislative chambers, of a nation, colony, or subnational division such as a province or state. It was commonly used to label unicameral or upper house legislative bodies in the Brit ...

. Piddington reprised his candidacy against Dibbs in Tamworth and was narrowly elected as a Free Trader, in what was regarded as a "highlight of the Reidites' triumph". With his parliamentary term beginning on 24 July 1895, Piddington was subsequently chosen by Reid to move the address-in-reply in the first session of the new parliament. In his maiden speech

A maiden speech is the first speech given by a newly elected or appointed member of a legislature or parliament.

Traditions surrounding maiden speeches vary from country to country. In many Westminster system governments, there is a convention th ...

and other parliamentary speeches he supported federation of the Australian colonies, reform of the Legislative Council, free trade, and a land tax

A land value tax (LVT) is a levy on the value of land without regard to buildings, personal property and other improvements upon it. Some economists favor LVT, arguing it does not cause economic inefficiency, and helps reduce economic inequali ...

based on Georgist

Georgism, in modern times also called Geoism, and known historically as the single tax movement, is an economic ideology holding that people should own the value that they produce themselves, while the economic rent derived from land—includ ...

principles. In 1895 he opposed the inclusion of a marriage bar in the Reid government's ''Public Service Bill'', describing it as "antediluvian". According to his biographer Michael Roe

Michael Roe (born October 12, 1954) is an American, singer, songwriter, and record producer. He is a founding member of the band the 77s and the Lost Dogs and has recorded several solo albums.

Career

Although he has released several solo album ...

, "his ideas were akin to Labor but membership of any party probably repelled him; he grasped Reid's good points, but the personality gap between himself and that dominating figure of the day was immense".

In spite of his support of Federation, Piddington was highly critical of the draft federal constitution adopted by the second constitutional convention in 1897 and campaigned for the "No" vote in the 1898 New South Wales referendum. In his view the draft constitution had succumbed to provincialism and would result in a Senate that was too powerful and undemocratic. Piddington's views likely contributed to his defeat in Tamworth after a single parliamentary term at the 1898 general election. Following Federation, he stood again in Tamworth at the 1901 election, but was again unsuccessful.

In 1910, Piddington was elected to the council of the University of Sydney. The following year, he was appointed as a Royal Commissioner by the Government of New South Wales

The Government of New South Wales, also known as the NSW Government, is the executive state government of New South Wales, Australia. The government comprises 11 portfolios, led by a ministerial department and supported by several agencies. Th ...

to inquire into labour shortages, and was appointed a commissioner again in 1913 to inquire into industrial arbitration in New South Wales. During this time he continued to practise law and was employed at Sydney Boys High School.

High Court appointment

Piddington was one of four Justices appointed to the High Court in 1913. The bench had been expanded from five to seven justices that year, and foundation justiceRichard O'Connor

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Richard Nugent O'Connor, (21 August 1889 – 17 June 1981) was a senior British Army Officer (armed forces), officer who fought in both the First World War, First and Second World Wars, and commanded the ...

had died late in 1912. The Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923. He led the nation during World War I, and his influence on national politics s ...

, under Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher (29 August 186222 October 1928) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the fifth prime minister of Australia from 1908 to 1909, 1910 to 1913 and 1914 to 1915. He held office as the leader of the Australian ...

, took the opportunity to try to stack the court. The Fisher Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

government put forward a constitutional referendum in 1911, proposing to give the federal government

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

increased power over corporations and industrial relations, and to allow it to nationalise

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with priv ...

monopolies

A monopoly (from Greek and ) is a market in which one person or company is the only supplier of a particular good or service. A monopoly is characterized by a lack of economic competition to produce a particular thing, a lack of viable sub ...

. It was defeated in all states but Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

. Fisher held another referendum in 1913 on the same issues, but that was also defeated. In this context, Fisher and Hughes were looking for justices who would have a broad interpretation of the Constitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia (also known as the Commonwealth Constitution) is the fundamental law that governs the political structure of Australia. It is a written constitution, which establishes the country as a Federation of Australia, ...

, particularly of Section 51, which divides powers between the federal and state governments. If the constitution was interpreted broadly, then the need for referendums might be circumvented.

Hughes contacted Piddington's brother-in-law

A sibling-in-law is the spouse of one's sibling or the sibling of one’s spouse.

More commonly, a sibling-in-law is referred to as a brother-in-law for a male sibling-in-law and a sister-in-law for a female sibling-in-law.

Sibling-in-law al ...

, poet and politician Dowell O'Reilly, to ask about Piddington's view on states' rights. O'Reilly was not sure, and contacted Piddington (who was arguing a case before the Privy Council in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

at the time) by telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas pi ...

. The message reached him in Port Said

Port Said ( , , ) is a port city that lies in the northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, straddling the west bank of the northern mouth of the Suez Canal. The city is the capital city, capital of the Port S ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

on 2 February. Piddington replied: "In sympathy with supremacy of Commonwealth powers." Hughes then officially offered Piddington an appointment, which he accepted. Both the New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

and Victorian Bars, and the press, spoke out against Piddington's appointment. '' The Bulletin'' led a strong media campaign against Piddington. William Irvine refused to welcome Piddington as a judge on behalf of the Victorian Bar. Ultimately Piddington resigned from the High Court one month after his appointment, having never sat at the bench. Hughes, who had been widely criticised for trying to stack the court, labelled Piddington a coward after the incident, and called him a "panic-stricken boy". p82.

Piddington was one of six justices of the High Court to have served in the Parliament of New South Wales

The Parliament of New South Wales, formally the Legislature of New South Wales, (definition of "The Legislature") is the bicameral legislative body of the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW). It consists of the Monarch, the New South Wa ...

, along with Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician, barrister and jurist who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903. He held office as the leader of the Protectionist Party, before ...

, Richard O'Connor, Adrian Knox

Sir Adrian Knox (29 November 186327 April 1932) was an Australian lawyer and judge who served as the second Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1919 to 1930.

Knox was born in Sydney, the son of businessman Sir Edward Knox. He studied ...

, Edward McTiernan and H. V. Evatt

Herbert Vere "Doc" Evatt, (30 April 1894 – 2 November 1965) was an Australian politician and judge. He served as a justice of the High Court of Australia from 1930 to 1940, Attorney-General of Australia, Attorney-General and Minister for For ...

.

Later life

Interstate Commission

In September 1913, Piddington was appointed as the chairman of the Interstate Commission byJoseph Cook

Sir Joseph Cook (7 December 1860 – 30 July 1947) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the sixth Prime Minister of Australia, prime minister of Australia from 1913 to 1914. He held office as the leader of the Fusion L ...

, the new Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fu ...

Prime Minister. It had been rumoured that Hughes would be appointed to that position, and it has been suggested that Cook appointed Piddington to spite Hughes, or to rebuke Hughes for turning on Piddington. Nevertheless, he remained Chairman until the legislation under which he and the other two commissioners had been appointed was invalidated by the High Court. In 1919 he was made a Commissioner in both the Royal Commission on the Sugar Industry and the Royal Commission on the Basic Wage. In 1913 he was made a King's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

.

Industrial Commission of New South Wales

From 1926, he served as President of the Industrial Commission of New South Wales. He held that position until 1932, when followingGovernor of New South Wales

The governor of New South Wales is the representative of the monarch, King Charles III, in the state of New South Wales. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia, Governor-General of Australia at the national level, the governor ...

Sir Philip Game

Sir Philip Woolcott Game (30 March 1876 – 4 February 1961) was a Royal Air Force commander, who later served as Governor of New South Wales and Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis (London). Born in Surrey in 1876, Game was educated at Cha ...

's dismissal of the Lang government, Piddington resigned in protest, despite being just a few weeks short of being entitled to a pension

A pension (; ) is a fund into which amounts are paid regularly during an individual's working career, and from which periodic payments are made to support the person's retirement from work. A pension may be either a " defined benefit plan", wh ...

.

Return to private practice and other activities

In 1934, Piddington was engaged by Czechoslovak writerEgon Kisch

Egon Erwin Kisch (29 April 1885 – 31 March 1948) was an Austro-Hungarian and Czechoslovak writer and journalist, who wrote in German. He styled himself ''Der Rasende Reporter'' (The Racing Reporter) for his countless travels to the far corners ...

to represent him in his cases against the Australian government, which sought to deport him for his left-wing political views. Kisch's attempted exclusion from Australia had become a ''cause célèbre''. Piddington appeared before the High Court in ''R v Carter; ex parte Kisch'' and was allowed to cross-examine immigration minister Thomas Paterson

Thomas Paterson (20 November 1882 – 24 January 1952) was an Australian politician who served as deputy leader of the Country Party from 1929 to 1937. He held ministerial office in the governments of Stanley Bruce and Joseph Lyons, represent ...

, with Justice H. V. Evatt

Herbert Vere "Doc" Evatt, (30 April 1894 – 2 November 1965) was an Australian politician and judge. He served as a justice of the High Court of Australia from 1930 to 1940, Attorney-General of Australia, Attorney-General and Minister for For ...

ultimately that the government had not demonstrated that Kisch was a "prohibited immigrant". Historian Nicholas Hasluck has suggested that Piddington "did not necessarily impress all of those associated with the case" and that Evatt had intervened with Piddington's junior to guide his argument.

Following Evatt's ruling, the government then attempted to secure Kisch's deportation by administering him a dictation test in Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

under the ''Immigration Restriction Act 1901

The ''Immigration Restriction Act 1901'' (Cth) was an Act of the Parliament of Australia which limited immigration to Australia and formed the basis of the White Australia policy which sought to exclude all non-Europeans from Australia. The l ...

''. This prompted a further High Court case, ''R v Wilson; ex parte Kisch'', where the full court ruled that Scottish Gaelic was not a language under the terms of the act. In a further case, ''R v Fletcher; ex parte Kisch'', Piddington represented Kisch in seeking damages from ''The Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily Tabloid (newspaper format), tabloid newspaper published in Sydney, Australia, and owned by Nine Entertainment. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuous ...

'' for scandalising the court in its criticism of the Wilson ruling. Evatt awarded costs to Kisch but did not punish the newspaper for contempt.

In 1940, Piddington returned to the High Court as a plaintiff. Two years earlier, he had been seriously injured when struck by a motorcycle while crossing Phillip Street in Sydney; he sued for negligence. Unsuccessful in the Supreme Court of New South Wales

The Supreme Court of New South Wales is the highest state court of the Australian States and territories of Australia, State of New South Wales. It has unlimited jurisdiction within the state in civil law (common law), civil matters, and hears ...

, he appealed to the High Court. Piddington won the appeal but was unsuccessful in the retrial in the Supreme Court.

Piddington's memoirs, "Worshipful Masters" was published in 1929.

Personal life

In 1896, Piddington married Marion Louisa O'Reilly, the daughter of an Anglican canon. She was active in the social reform of liberal sex education and as a promoter ofeugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

. Their son Ralph

Ralph (pronounced or ) is a male name of English origin, derived from the Old English ''Rædwulf'' and Old High German ''Radulf'', cognate with the Old Norse ''Raðulfr'' (''rað'' "counsel" and ''ulfr'' "wolf").

The most common forms are:

* Ra ...

became professor of anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

at the University of Auckland

The University of Auckland (; Māori: ''Waipapa Taumata Rau'') is a public research university based in Auckland, New Zealand. The institution was established in 1883 as a constituent college of the University of New Zealand. Initially loc ...

.

Piddington died in Mosman

Mosman is a suburb on the Lower North Shore region of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Mosman is located 8 kilometres north-east of the Sydney central business district and is the administrative centre for the local governm ...

on 5 June 1945.

References

Sources

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Piddington, Albert Bathurst 1862 births 1945 deaths Justices of the High Court of Australia Members of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly People educated at Sydney Grammar School University of Sydney alumni Australian King's Counsel Colony of New South Wales people