Akutan Zero on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Akutan Zero, also known as Koga's Zero (古賀のゼロ) and the Aleutian Zero, was a Mitsubishi A6M2 Model 21 Zero Japanese

The Akutan Zero, also known as Koga's Zero (古賀のゼロ) and the Aleutian Zero, was a Mitsubishi A6M2 Model 21 Zero Japanese

The

The

In June 1942, as part of the Japanese Midway operation, the Japanese attacked the Aleutian islands, off the south coast of

In June 1942, as part of the Japanese Midway operation, the Japanese attacked the Aleutian islands, off the south coast of

File:Akutan on Alaska location map.png, Location of Akutan in Alaska

File:AkutanZero3.jpg, The Zero trailing oil over Dutch Harbor, moments after being hit

The crash site, which was out of sight of standard flight lanes and not visible by ship, remained undetected and undisturbed for over a month. On July 10, 1942, an American PBY Catalina piloted by Lieutenant William "Bill" Thies spotted the wreckage. Thies's Catalina had been patrolling by dead reckoning and had become lost. On spotting the Shumagin Islands, he reoriented his plane and began to return to Dutch Harbor by the most direct course: over Akutan Island. Machinist Mate Albert Knack, who was the plane captain (note: the term "plane captain" in US Navy usage refers to an aircraft's assigned maintenance crew chief, not the pilot-in-command), spotted Koga's wreck. Thies's plane circled the crash site for several minutes, noted its position on the map, and returned to Dutch Harbor to report it. Thies persuaded his commanding officer, Paul Foley, to let him return with a salvage team. The next day (July 11), the team flew out to inspect the wreck. Navy photographer's mate Arthur W. Bauman took pictures as they worked.

Thies's team extracted Koga's body from the plane by having Knack (the smallest crew member) crawl up inside the plane and cut his safety harness with a knife. They searched it for anything with intelligence value, and buried Koga in a shallow grave near the crash site. Thies returned with his team to Dutch Harbor, where he reported the plane as salvageable. The next day (July 12), a salvage team under Lieutenant Robert Kirmse was dispatched to Akutan. This team gave Koga a Christian burial in a nearby knoll and set about recovering the plane, but the lack of heavy equipment (which they had been unable to unload after the delivery ship lost two anchors) frustrated their efforts. On July 15, a third recovery team was dispatched. This time, with proper heavy equipment, the team was able to free the Zero from the mud and haul it overland to a nearby

The crash site, which was out of sight of standard flight lanes and not visible by ship, remained undetected and undisturbed for over a month. On July 10, 1942, an American PBY Catalina piloted by Lieutenant William "Bill" Thies spotted the wreckage. Thies's Catalina had been patrolling by dead reckoning and had become lost. On spotting the Shumagin Islands, he reoriented his plane and began to return to Dutch Harbor by the most direct course: over Akutan Island. Machinist Mate Albert Knack, who was the plane captain (note: the term "plane captain" in US Navy usage refers to an aircraft's assigned maintenance crew chief, not the pilot-in-command), spotted Koga's wreck. Thies's plane circled the crash site for several minutes, noted its position on the map, and returned to Dutch Harbor to report it. Thies persuaded his commanding officer, Paul Foley, to let him return with a salvage team. The next day (July 11), the team flew out to inspect the wreck. Navy photographer's mate Arthur W. Bauman took pictures as they worked.

Thies's team extracted Koga's body from the plane by having Knack (the smallest crew member) crawl up inside the plane and cut his safety harness with a knife. They searched it for anything with intelligence value, and buried Koga in a shallow grave near the crash site. Thies returned with his team to Dutch Harbor, where he reported the plane as salvageable. The next day (July 12), a salvage team under Lieutenant Robert Kirmse was dispatched to Akutan. This team gave Koga a Christian burial in a nearby knoll and set about recovering the plane, but the lack of heavy equipment (which they had been unable to unload after the delivery ship lost two anchors) frustrated their efforts. On July 15, a third recovery team was dispatched. This time, with proper heavy equipment, the team was able to free the Zero from the mud and haul it overland to a nearby  The Akutan Zero was loaded onto the and transported to Seattle, arriving on August 1. From there, it was transported by barge to Naval Air Station North Island near San Diego where repairs were carefully carried out. These repairs "consisted mostly of straightening the vertical stabilizer, rudder, wing tips, flaps, and canopy. The sheared-off landing struts needed more extensive work. The three-blade Sumitomo

The Akutan Zero was loaded onto the and transported to Seattle, arriving on August 1. From there, it was transported by barge to Naval Air Station North Island near San Diego where repairs were carefully carried out. These repairs "consisted mostly of straightening the vertical stabilizer, rudder, wing tips, flaps, and canopy. The sheared-off landing struts needed more extensive work. The three-blade Sumitomo

Data from the captured Zero had been transmitted to the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) and Grumman Aircraft. After careful study, Roy Grumman decided that he could design an aircraft that could match or surpass the Zero in most respects, except range, without sacrificing pilot armor, self-sealing fuel tanks, and a sturdy fuselage structure. The new F6F Hellcat would compensate for the extra weight with additional power.Thruelsen p. 178

On September 20, 1942, two months after the Zero's capture, Lieutenant Commander Eddie R. Sanders took the Akutan Zero up for its first test flight. He made 24 test flights between September 20 and October 15. According to Sanders' report:

Data from the captured Zero had been transmitted to the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) and Grumman Aircraft. After careful study, Roy Grumman decided that he could design an aircraft that could match or surpass the Zero in most respects, except range, without sacrificing pilot armor, self-sealing fuel tanks, and a sturdy fuselage structure. The new F6F Hellcat would compensate for the extra weight with additional power.Thruelsen p. 178

On September 20, 1942, two months after the Zero's capture, Lieutenant Commander Eddie R. Sanders took the Akutan Zero up for its first test flight. He made 24 test flights between September 20 and October 15. According to Sanders' report:

In early 1943, the Zero was transferred from Naval Air Station North Island to Anacostia Naval Air Station. The Navy wished to make use of the expertise of the

In early 1943, the Zero was transferred from Naval Air Station North Island to Anacostia Naval Air Station. The Navy wished to make use of the expertise of the

Nine wrecked

Nine wrecked

Fire in the Sky: The Air War in the South Pacific

'. Westview Press, 2001, . * Handel, Michael I.

War, Strategy, and Intelligence

'. Routledge, 1989. . * Ewing, Steve (2002).

Reaper Leader, The Life of Jimmy Flatley

'' Naval Institute Press. . * Ewing, Steve (2004).

Thach Weave, The Life of Jimmie Thach

'' Naval Institute Press. . * Francillon, Rene J. (1989).

Grumman Aircraft Since 1929

'' Naval Institute Press. . * Lundstrom, John B.

The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign: Naval Fighter Combat from August to November 1942

'.

United States Naval Fighters of World War II in Action

'. Poole, Dorset, UK: Blandford Press, 1980. . *

The Oxford Companion to World War II

'. Edited by I.C.B. Dear. Oxford University Press, 1995. . * Rearden, Jim.

Koga's Zero: The Fighter That Changed World War II

'. , second edition. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1995. Originally published as ''Cracking the Zero Mystery: How the U.S. Learned to Beat Japan's Vaunted WWII Fighter Plane''. . * Rearden, Jim.

Koga's Zero – An Enemy Plane That Saved American Lives

'. ''Invention and Technology Magazine''. Volume 13, Issue 2, Fall 1997. Retrieved on 2008-12-09. * Degan, Patrick

Flattop Fighting in World War II

'. McFarland, 2003. . * Thruelsen, Richard (1976).

The Grumman Story

'' Praeger Publishers, .

Bill Thies's website

Ben Schapiro. The Warbird's Forum, May 2008 – An article describing the capture and repair of Gerhard Neumann's Zero in China in 1941.

War Prize: The Capture Of The First Japanese Zero Fighter In 1941

James F. Lansdale. j-aircraft.com, December 3, 1999. A second article describing the capture and repair of Gerhard Neumann's Zero.

20th-century aircraft shootdown incidents Akutan Island Aleutian Islands campaign Individual aircraft of World War II

The Akutan Zero, also known as Koga's Zero (古賀のゼロ) and the Aleutian Zero, was a Mitsubishi A6M2 Model 21 Zero Japanese

The Akutan Zero, also known as Koga's Zero (古賀のゼロ) and the Aleutian Zero, was a Mitsubishi A6M2 Model 21 Zero Japanese fighter aircraft

Fighter aircraft (early on also ''pursuit aircraft'') are military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat. In military conflict, the role of fighter aircraft is to establish air supremacy, air superiority of the battlespace. Domina ...

piloted by Petty Officer Tadayoshi Koga, that crash-landed on Akutan Island, Alaska Territory, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. It was found intact by the Americans in July 1942 and became the first Zero acquired by the United States during the war that could be restored to airworthy condition. It was repaired and flown by American test pilots. As a result of information gained from these tests, American tacticians were able to devise ways to defeat the Zero, which was the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

's primary fighter plane throughout the war.

The Akutan Zero has been described as "a prize almost beyond value to the United States", and "probably one of the greatest prizes of the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

". Japanese historian and JASDF lieutenant general Masatake Okumiya stated that the acquisition of the Akutan Zero "was no less serious" than the Japanese defeat at the Battle of Midway, and that it "did much to hasten Japan's final defeat".Okumiya, pp. 160–63 Nonetheless, historian John Lundstrom and others challenge "the contention that it took dissection of Koga's Zero to create tactics that beat the fabled airplane".Lundstrom, p. 535. The Akutan Zero was destroyed in a training accident in 1945. Parts of it are preserved in several museums in the United States.

Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter

The

The Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

began in 1937. Attacks by Chinese fighter planes on Japanese bombers led the Japanese to develop the concept of fighter escorts. The limited range of the Mitsubishi A5M

The Mitsubishi A5M, formal Japanese Navy designation , experimental Navy designation Mitsubishi Navy Experimental 9-''Shi'' Carrier Fighter, company designation Mitsubishi ''Ka''-14, was a WWII-era Japanese Aircraft carrier, carrier-based fighter ...

"Claude" fighter used to escort the bombers caused the Japanese Navy Air staff to commission the Mitsubishi A6M Zero as a long-range land- and carrier-based fighter.Rearden, ''Fighter'', pp. 1–3.

The Zero, which first flew in 1939, was exceedingly agile and lightweight, with maneuverability and range superior to any other fighter in the world at that time. In 1940 Claire Lee Chennault, leader of the Flying Tigers

The First American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Republic of China Air Force, nicknamed the Flying Tigers, was formed to help oppose the Japanese invasion of China. Operating in 1941–1942, it was composed of pilots from the United States Ar ...

, wrote a report to warn his home country of the Zero's performance. However, United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army, als ...

analysts rejected the Chennault report as "arrant nonsense" and concluded the performance attributed to the Zero was an aerodynamic impossibility. With the coming of war, the U.S. fighting services learned better; the Zero's maneuverability outperformed any Allied fighter it encountered for the first two years of the war. According to American flying ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviation, military aviator credited with shooting down a certain minimum number of enemy aircraft during aerial combat; the exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ...

William N. Leonard, "In these early encounters and on our own we were learning the folly of dogfighting with the Zero".

To achieve this dogfighting agility, however, Japanese engineers had traded off durability. The Zero was very lightly built; it had no armor and no self-sealing fuel tank

A self-sealing fuel tank (SSFT) is a type of fuel tank, typically used in aircraft fuel tanks or fuel bladders, that prevents them from leaking fuel and igniting after being damaged.

Typical self-sealing tanks have layers of rubber and reinfor ...

s. According to American author Jim Rearden, "The Zero was probably the easiest fighter of any in World War II to bring down when hit ... The Japanese ... were not prepared to or weren't capable of building more advanced fighters in the numbers needed to cope with increasing numbers and quality of American fighters".Rearden, ''Fighter'', p. 10. The Zero was the primary Japanese Navy fighter throughout the war. During the war, the Japanese manufactured roughly 10,500 Zeros.

Nine Zeros were shot down during the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

. From these wrecks, the Allies learned that the Zero lacked armor and self-sealing fuel tanks, but little else about its capabilities. The Zero's flight performance characteristics—crucial to devising tactics and machinery to combat it—remained a mystery.

Three other downed Zeros were available to the Allies before the Akutan Zero was recovered. In February 1942, a Zero (serial number 5349) piloted by Hajime Toyoshima crashed on Melville Island in Australia after the bombing of Darwin; it was heavily damaged. Another Zero, piloted by Yoshimitsu Maeda, crashed near Cape Rodney, New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

. The team sent to recover the plane erred when they chopped off the wings, severing the wing spars and rendering the hulk unflyable.Rearden, ''Fighter'', p. 30. The third came from China, where Gerhard Neumann reconstructed a working aircraft from a partly intact Zero (serial number 3372) that had landed in Chinese territory plus salvaged pieces from other downed Zeros. Neumann's aircraft did not reach the United States for testing until after the recovery of the Akutan Zero.

Petty Officer Koga's final mission

In June 1942, as part of the Japanese Midway operation, the Japanese attacked the Aleutian islands, off the south coast of

In June 1942, as part of the Japanese Midway operation, the Japanese attacked the Aleutian islands, off the south coast of Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

. A Japanese task force led by Admiral Kakuji Kakuta bombed Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island twice, once on June 3 and again the following day.

Tadayoshi Koga (September 10, 1922 – June 4, 1942), a 19-year-old flight petty officer first class, was launched from the Japanese aircraft carrier as part of the June 4 raid. Koga was part of a three-plane section; his wingmen were Chief Petty Officer Makoto Endo and Petty Officer Tsuguo Shikada. Koga and his comrades attacked Dutch Harbor, and are believed to be the three Zeroes that shot down an American PBY-5A Catalina flying boat piloted by Bud Mitchell, and strafed its survivors in the water, killing Mitchell and all six of his crewmen. In the process, Koga's plane (serial number 4593) was damaged by small arms fire.Rearden, ''Fighter'', p. 54.

Tsuguo Shikada, one of Koga's wingmen, published an account in 1984 in which he claimed the damage to Koga's plane occurred while his section was making an attack against two American Catalinas anchored in the bay. This account omits any mention of shooting down Mitchell's PBY. Both American and Japanese records contradict his claims; there were no PBYs in the bay that day. However, his claims do match American records from the attack against Dutch Harbor the previous day (June 3). Rearden noted, "It seems likely that in the near half-century after the event Shikada's memory confused the raids of June 3 and June 4 ... It also seems likely that in his interview, Shikada employed selective memory in not mentioning shooting down Mitchell's PBY and then machine-gunning the crew on the water".

It is not known who fired the shot that brought down Koga's plane, although numerous individuals have claimed credit. Photographic evidence strongly suggests it was hit by ground fire. Members of the 206th Coast Artillery Regiment, which had both 3-inch anti-aircraft guns and .50-caliber machine guns in position defending Dutch Harbor, claimed credit, in addition to claims made by United States Navy ships that were present. Physical inspection of the plane revealed it was hit with small arms

A firearm is any type of gun that uses an explosive charge and is designed to be readily carried and operated by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see legal definitions).

The first firearms originate ...

fire: .50 caliber bullet holes and smaller, from both above and below.

Crash

The fatal shot severed the return oil line, and Koga's plane immediately began trailing oil. Koga reduced speed to keep the engine from seizing for as long as possible. The plane's landing gear mired in the water and mud, causing the plane to flip upside down and skid to a stop. Although the aircraft survived the landing nearly intact, Petty Officer Koga died instantly on impact, probably from a broken neck or a blunt-force blow to his head. Koga's wingmen, circling above, had orders to destroy any Zeros that crash-landed in enemy territory, but as they did not know if Koga was still alive, they could not bring themselves to strafe his plane. They decided to leave without firing on it. The Japanese submarine stationed off Akutan Island to pick up pilots searched for Koga in vain before being driven off by the destroyer . (Note: The description above is solely based on "Koga's Zero" by American author Jim Rearden.The claim that the Japanese Zero fighter pilots were ordered to destroy their wingmen if they fell into enemy territory has not been confirmed by Japanese researchers or supported by Japanese records, including the memoirs of Zero fighter pilots published in succession in Japanese several years after the war. Furthermore: 1) Attacking a downed aircraft from the air would have been technically difficult, even for highly skilled pilots. 2) Even if they managed to hit it, completely destroying an already downed aircraft would have been extremely challenging. 3) This suggests that to truly prevent a Zero from falling into enemy hands for analysis, it would need to be shot down while still in flight. 4) In military contexts, including Japan's, even if accidental, shooting a comrade during combat would result in a court-martial.)Recovery

The crash site, which was out of sight of standard flight lanes and not visible by ship, remained undetected and undisturbed for over a month. On July 10, 1942, an American PBY Catalina piloted by Lieutenant William "Bill" Thies spotted the wreckage. Thies's Catalina had been patrolling by dead reckoning and had become lost. On spotting the Shumagin Islands, he reoriented his plane and began to return to Dutch Harbor by the most direct course: over Akutan Island. Machinist Mate Albert Knack, who was the plane captain (note: the term "plane captain" in US Navy usage refers to an aircraft's assigned maintenance crew chief, not the pilot-in-command), spotted Koga's wreck. Thies's plane circled the crash site for several minutes, noted its position on the map, and returned to Dutch Harbor to report it. Thies persuaded his commanding officer, Paul Foley, to let him return with a salvage team. The next day (July 11), the team flew out to inspect the wreck. Navy photographer's mate Arthur W. Bauman took pictures as they worked.

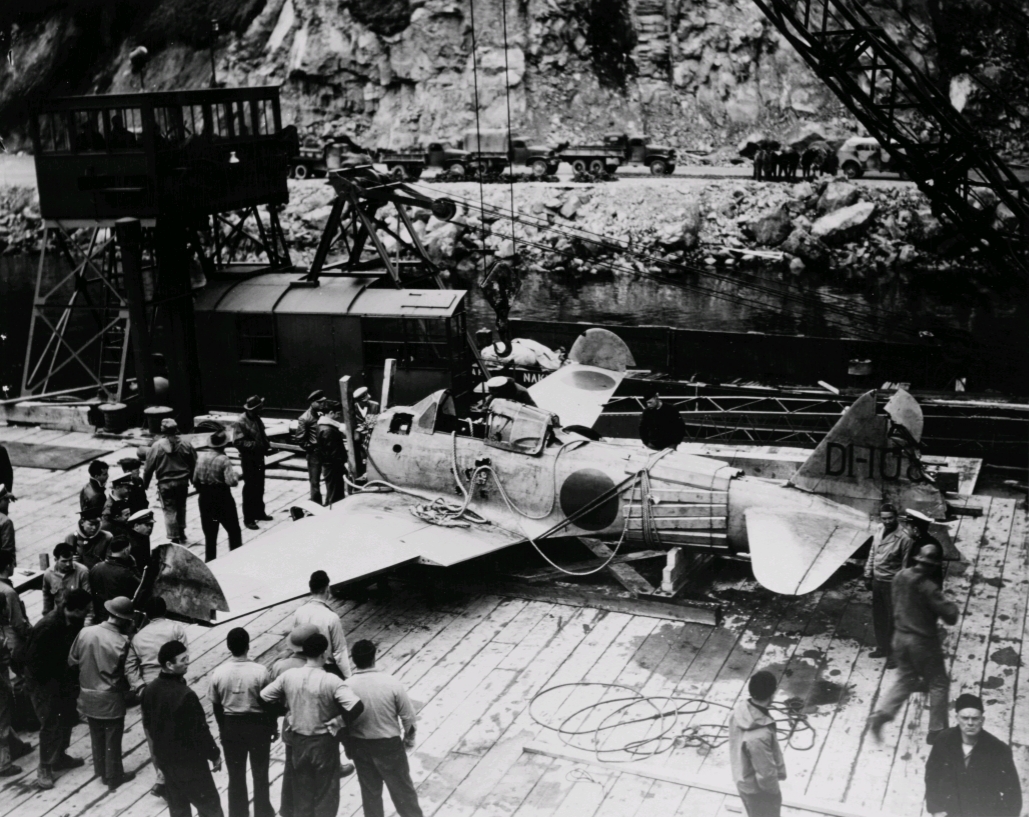

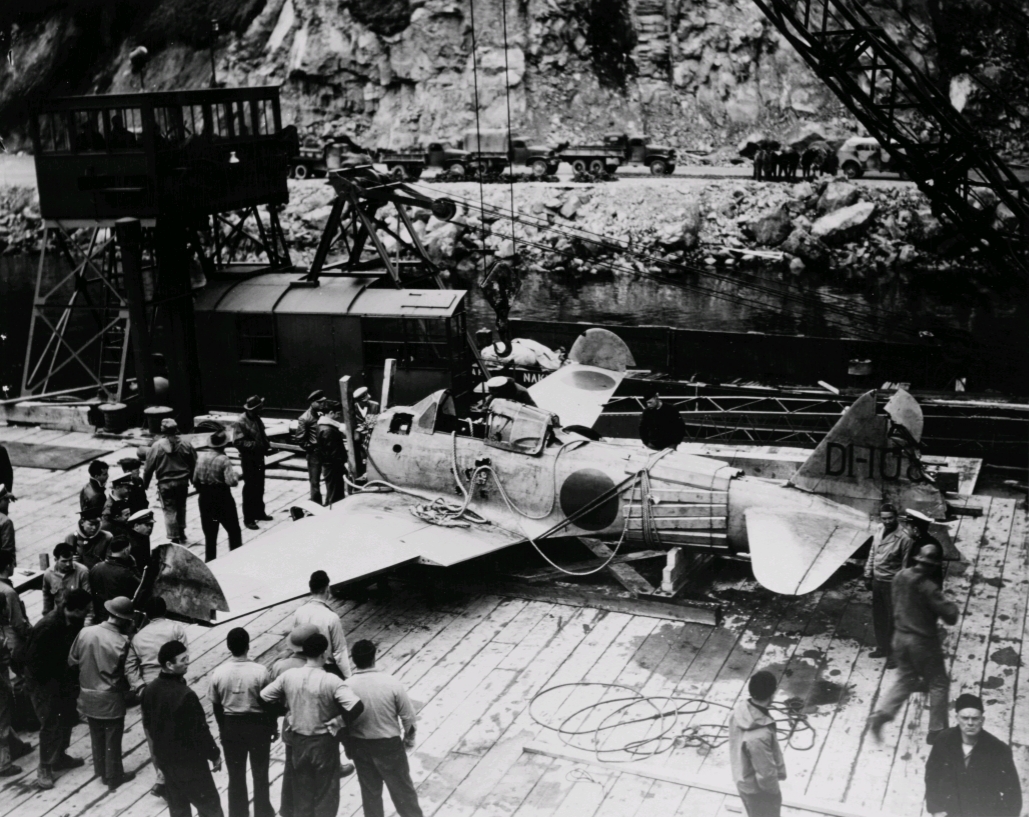

Thies's team extracted Koga's body from the plane by having Knack (the smallest crew member) crawl up inside the plane and cut his safety harness with a knife. They searched it for anything with intelligence value, and buried Koga in a shallow grave near the crash site. Thies returned with his team to Dutch Harbor, where he reported the plane as salvageable. The next day (July 12), a salvage team under Lieutenant Robert Kirmse was dispatched to Akutan. This team gave Koga a Christian burial in a nearby knoll and set about recovering the plane, but the lack of heavy equipment (which they had been unable to unload after the delivery ship lost two anchors) frustrated their efforts. On July 15, a third recovery team was dispatched. This time, with proper heavy equipment, the team was able to free the Zero from the mud and haul it overland to a nearby

The crash site, which was out of sight of standard flight lanes and not visible by ship, remained undetected and undisturbed for over a month. On July 10, 1942, an American PBY Catalina piloted by Lieutenant William "Bill" Thies spotted the wreckage. Thies's Catalina had been patrolling by dead reckoning and had become lost. On spotting the Shumagin Islands, he reoriented his plane and began to return to Dutch Harbor by the most direct course: over Akutan Island. Machinist Mate Albert Knack, who was the plane captain (note: the term "plane captain" in US Navy usage refers to an aircraft's assigned maintenance crew chief, not the pilot-in-command), spotted Koga's wreck. Thies's plane circled the crash site for several minutes, noted its position on the map, and returned to Dutch Harbor to report it. Thies persuaded his commanding officer, Paul Foley, to let him return with a salvage team. The next day (July 11), the team flew out to inspect the wreck. Navy photographer's mate Arthur W. Bauman took pictures as they worked.

Thies's team extracted Koga's body from the plane by having Knack (the smallest crew member) crawl up inside the plane and cut his safety harness with a knife. They searched it for anything with intelligence value, and buried Koga in a shallow grave near the crash site. Thies returned with his team to Dutch Harbor, where he reported the plane as salvageable. The next day (July 12), a salvage team under Lieutenant Robert Kirmse was dispatched to Akutan. This team gave Koga a Christian burial in a nearby knoll and set about recovering the plane, but the lack of heavy equipment (which they had been unable to unload after the delivery ship lost two anchors) frustrated their efforts. On July 15, a third recovery team was dispatched. This time, with proper heavy equipment, the team was able to free the Zero from the mud and haul it overland to a nearby barge

A barge is typically a flat-bottomed boat, flat-bottomed vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. Original use was on inland waterways, while modern use is on both inland and ocean, marine water environments. The firs ...

, without further damaging it. The Zero was taken to Dutch Harbor, turned right-side up, and cleaned.

The Akutan Zero was loaded onto the and transported to Seattle, arriving on August 1. From there, it was transported by barge to Naval Air Station North Island near San Diego where repairs were carefully carried out. These repairs "consisted mostly of straightening the vertical stabilizer, rudder, wing tips, flaps, and canopy. The sheared-off landing struts needed more extensive work. The three-blade Sumitomo

The Akutan Zero was loaded onto the and transported to Seattle, arriving on August 1. From there, it was transported by barge to Naval Air Station North Island near San Diego where repairs were carefully carried out. These repairs "consisted mostly of straightening the vertical stabilizer, rudder, wing tips, flaps, and canopy. The sheared-off landing struts needed more extensive work. The three-blade Sumitomo propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

was dressed and re-used." The Zero's red '' Hinomaru'' roundel was repainted with the American blue-circle-white-star insignia. The whole time, the plane was kept under 24-hour military police

Military police (MP) are law enforcement agencies connected with, or part of, the military of a state. Not to be confused with civilian police, who are legally part of the civilian populace. In wartime operations, the military police may supp ...

guard in order to deter would-be souvenir hunters from damaging the plane. The Zero was fit to fly again on September 20.

Analysis

Data from the captured Zero had been transmitted to the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) and Grumman Aircraft. After careful study, Roy Grumman decided that he could design an aircraft that could match or surpass the Zero in most respects, except range, without sacrificing pilot armor, self-sealing fuel tanks, and a sturdy fuselage structure. The new F6F Hellcat would compensate for the extra weight with additional power.Thruelsen p. 178

On September 20, 1942, two months after the Zero's capture, Lieutenant Commander Eddie R. Sanders took the Akutan Zero up for its first test flight. He made 24 test flights between September 20 and October 15. According to Sanders' report:

Data from the captured Zero had been transmitted to the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) and Grumman Aircraft. After careful study, Roy Grumman decided that he could design an aircraft that could match or surpass the Zero in most respects, except range, without sacrificing pilot armor, self-sealing fuel tanks, and a sturdy fuselage structure. The new F6F Hellcat would compensate for the extra weight with additional power.Thruelsen p. 178

On September 20, 1942, two months after the Zero's capture, Lieutenant Commander Eddie R. Sanders took the Akutan Zero up for its first test flight. He made 24 test flights between September 20 and October 15. According to Sanders' report:

In early 1943, the Zero was transferred from Naval Air Station North Island to Anacostia Naval Air Station. The Navy wished to make use of the expertise of the

In early 1943, the Zero was transferred from Naval Air Station North Island to Anacostia Naval Air Station. The Navy wished to make use of the expertise of the NACA

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was a United States federal agency that was founded on March 3, 1915, to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research. On October 1, 1958, the agency was dissolved and its ...

Langley Research Center in flight instrumentation, and it was flown to Langley on March 5, 1943, for the installation of the instrumentation. While there, it underwent aerodynamic tests in the Full-Scale Wind Tunnel under conditions of strict secrecy. This work included wake surveys to determine the drag of aircraft components; tunnel scale measurements of lift, drag, control effectiveness; and sideslip tests.

After its return to the Navy, it was flight tested by Frederick M. Trapnell, the Anacostia Naval Air Station director of flight testing. He flew the Akutan Zero in performance maneuvers while Sanders simultaneously flew American planes performing identical maneuvers, simulating aerial combat. Following these, USN test pilot Lieutenant Melvin C. "Boogey" Hoffman conducted more dogfighting tests between himself flying the Akutan Zero and recently commissioned USN pilots flying newer Navy aircraft.

Later in 1943, the aircraft was displayed at Washington National Airport as a war prize. In 1944, it was recalled to North Island for use as a training plane for rookie pilots being sent to the Pacific. A model 52 Zero, captured during the liberation of Guam, was later used as well.

Data and conclusions from these tests were published in ''Informational Intelligence Summary 59'', ''Technical Aviation Intelligence Brief #3'', ''Tactical and Technical Trends #5'' (published prior to the first test flight), and ''Informational Intelligence Summary 85''. These results tend to somewhat understate the Zero's capabilities.

Consequences

Data from the captured aircraft were submitted to the BuAer andGrumman

The Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, later Grumman Aerospace Corporation, was a 20th century American producer of military and civilian aircraft. Founded on December 6, 1929, by Leroy Grumman and his business partners, it merged in 19 ...

for study in 1942. The U.S. carrier-borne fighter plane that succeeded the Grumman F4F Wildcat,Degan, ''Flattop'', p. 103. the F6F Hellcat, was tested in its first experimental mode as the XF6F-1 prototype with an under-powered Wright R-2600 ''Twin Cyclone'' 14-cylinder, two-row radial engine on 26 June 1942.O'Leary, pp. 67–74. Shortly before the XF6F-1's first flight, and based on combat accounts of encounters between the F4F Wildcat and A6M Zero, on 26 April 1942, BuAer directed Grumman to install the more powerful 18-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp

The Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp is an American twin-row, 18-cylinder, air-cooled radial aircraft engine with a displacement of , and is part of the long-lived Wasp family of engines.

The R-2800 saw widespread use in many important ...

radial engine—already powering Chance Vought's Corsair design since its beginnings in 1940—in the second XF6F-1 prototype. Grumman complied by redesigning and strengthening the F6F airframe to incorporate the 2,000 hp (1,500 kW) R-2800-10 engine, driving a three-bladed Hamilton Standard

Hamilton Standard was an American aircraft propeller (aircraft), propeller parts supplier. It was formed in 1929 when United Aircraft and Transport Corporation consolidated Hamilton Aero Manufacturing and Standard Steel Propeller into the Hamilto ...

propeller. With this combination, Grumman estimated the XF6F-3's performance would surpass that of the XF6F-1 by 25%.Sullivan 1979, p. 4. This first Double Wasp-equipped Hellcat airframe, bearing BuAer serial number 02982, first flew on 30 July 1942. The F6F-3 subtype had been designed with specific "Wildcat vs Zero" input from F4F pilots who fought in the Battle of the Coral Sea, such as Jim Flatley, and the Battle of Midway, such as Jimmy Thach; their input was obtained during a meeting with Grumman Vice President Jake Swirbul at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

on 23 June 1942. The first production F6F-3 made its first flight just over three months later, on October 3, 1942. While the captured Zero's tests did not drastically influence the Hellcat's design, they did impart knowledge of the Zero's handling characteristics, including its limitations in rolling right and diving. That information, together with the improved capabilities of the Hellcat, were credited with helping American pilots "tip the balance in the Pacific". American aces Kenneth A. Walsh and R. Robert Porter, among others, credited tactics derived from this knowledge with saving their lives.Rearden, ''Fighter'', p. 88. James Sargent Russell, who commanded the PBY Catalina squadron that discovered the Zero and later rose to the rank of admiral, said that Koga's Zero was "of tremendous historical significance". William N. Leonard concurred: "The captured Zero was a treasure. To my knowledge, no other captured machine has ever unlocked so many secrets at a time when the need was so great."

Some historians dispute the degree to which the Akutan Zero influenced the outcome of the air war in the Pacific. For example, the Thach Weave, a tactic created by John Thach and used with great success by American airmen against the Zero, was devised by Thach before the attack on Pearl Harbor, based on intelligence reports on the Zero's performance in China.

Nine wrecked

Nine wrecked Mitsubishi A6M Zero

The Mitsubishi A6M "Zero" is a long-range carrier-capable fighter aircraft formerly manufactured by Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. It was operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) from 1940 to 1945. The ...

s were recovered from Pearl Harbor shortly after the attack in December 1941, and United States Office of Naval Intelligence

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) is the military intelligence agency of the United States Navy. Established in 1882 primarily to advance the Navy's modernization efforts, it is the oldest member of the U.S. Intelligence Community and serv ...

, along with BuAer had them studied, and then shipped to the Experimental Engineering Department at Dayton, Ohio

Dayton () is a city in Montgomery County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of cities in Ohio, sixth-most populous city in Ohio, with a population of 137,644 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The Dayton metro ...

in 1942. It was noted that the ''experimental'' Grumman XF6F-1s then undergoing testing in June 1942 and the Zero had "wings integrated with the fuselage," an unusual design feature in American aircraft of the day.

The Akutan Zero was destroyed during a training accident in February 1945. While the Zero was taxiing for a take-off, a Curtiss SB2C Helldiver lost control and rammed into it. The Helldiver's propeller sliced the Zero into pieces. From the wreckage, William N. Leonard salvaged several gauges, which he donated to the National Museum of the United States Navy. The Alaska Heritage Museum and the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum (NASM) of the Smithsonian Institution is a museum in Washington, D.C., in the United States, dedicated to history of aviation, human flight and space exploration.

Established in 1946 as the National Air Museum, ...

also have small pieces of the Zero.

American author Jim Rearden led a search on Akutan in 1988 in an attempt to repatriate Koga's body. He located Koga's grave, but found it empty. Rearden and Japanese businessman Minoru Kawamoto conducted a records search. They found that Koga's body had been exhumed by an American Graves Registration Service team in 1947, and re-buried on Adak Island, further down the Aleutian chain. The team, unaware of Koga's identity, marked his body as unidentified. The Adak cemetery was excavated in 1953, and 236 bodies were returned to Japan. The body buried next to Koga (Shigeyoshi Shindo) was one of 13 identified; the remaining 223 unidentified remains were cremated and interred in Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery in Japan. It is probable that Koga was one of them.Rearden, ''Fighter'', pp. 95–98.

Notes

Sources

* Bergerud, Eric M.Fire in the Sky: The Air War in the South Pacific

'. Westview Press, 2001, . * Handel, Michael I.

War, Strategy, and Intelligence

'. Routledge, 1989. . * Ewing, Steve (2002).

Reaper Leader, The Life of Jimmy Flatley

'' Naval Institute Press. . * Ewing, Steve (2004).

Thach Weave, The Life of Jimmie Thach

'' Naval Institute Press. . * Francillon, Rene J. (1989).

Grumman Aircraft Since 1929

'' Naval Institute Press. . * Lundstrom, John B.

The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign: Naval Fighter Combat from August to November 1942

'.

Naval Institute Press

The United States Naval Institute (USNI) is a private non-profit military association that offers independent, nonpartisan forums for debate of national security issues. In addition to publishing magazines and books, the Naval Institute holds se ...

, 2005. .

* Okumiya, Masatake, Jiro Horikoshi

was a Japanese aeronautical engineer. He was the chief engineer of several Empire of Japan, Japanese Fighter aircraft, fighter aircraft designs used during World War II, most notably the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter, as well as the NAMC YS-11.

E ...

, and Martin Caidin. ''Zero!'' New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1956.

* O'Leary, Michael. United States Naval Fighters of World War II in Action

'. Poole, Dorset, UK: Blandford Press, 1980. . *

The Oxford Companion to World War II

'. Edited by I.C.B. Dear. Oxford University Press, 1995. . * Rearden, Jim.

Koga's Zero: The Fighter That Changed World War II

'. , second edition. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1995. Originally published as ''Cracking the Zero Mystery: How the U.S. Learned to Beat Japan's Vaunted WWII Fighter Plane''. . * Rearden, Jim.

Koga's Zero – An Enemy Plane That Saved American Lives

'. ''Invention and Technology Magazine''. Volume 13, Issue 2, Fall 1997. Retrieved on 2008-12-09. * Degan, Patrick

Flattop Fighting in World War II

'. McFarland, 2003. . * Thruelsen, Richard (1976).

The Grumman Story

'' Praeger Publishers, .

External links

{{Wikisource, Informational Intelligence Summary No. 85Bill Thies's website

Ben Schapiro. The Warbird's Forum, May 2008 – An article describing the capture and repair of Gerhard Neumann's Zero in China in 1941.

War Prize: The Capture Of The First Japanese Zero Fighter In 1941

James F. Lansdale. j-aircraft.com, December 3, 1999. A second article describing the capture and repair of Gerhard Neumann's Zero.

20th-century aircraft shootdown incidents Akutan Island Aleutian Islands campaign Individual aircraft of World War II