Ahasver on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Wandering Jew (occasionally referred to as the Eternal Jew, a

A variety of names have since been given to the Wandering Jew, including ''Matathias'', ''Buttadeus'' and ''Isaac Laquedem'', which is a name for him in France and the

A variety of names have since been given to the Wandering Jew, including ''Matathias'', ''Buttadeus'' and ''Isaac Laquedem'', which is a name for him in France and the

The later amalgamation of the fate of the specific figure of legend with the condition of the Jewish people as a whole, well established by the 18th century, had its precursor even in early Christian views of Jews and the diaspora. Extant manuscripts have shown that as early as the time of

The later amalgamation of the fate of the specific figure of legend with the condition of the Jewish people as a whole, well established by the 18th century, had its precursor even in early Christian views of Jews and the diaspora. Extant manuscripts have shown that as early as the time of

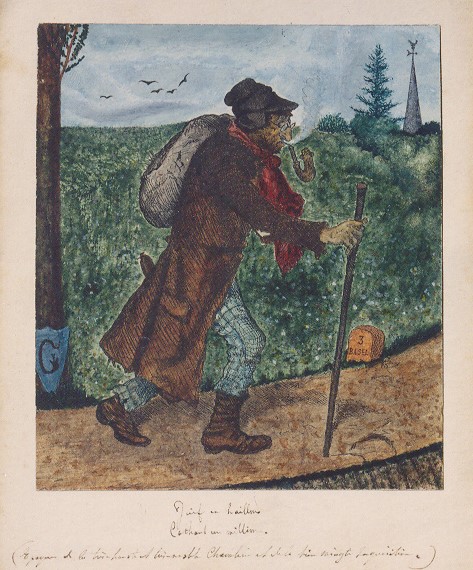

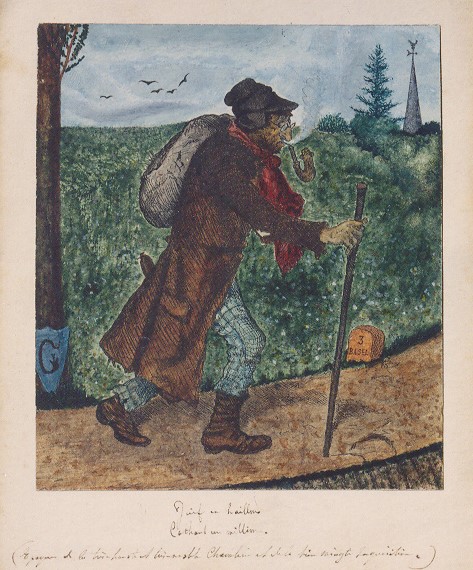

Nineteenth-century works depicting the legendary figure as the Wandering (or Eternal) Jew or as

Nineteenth-century works depicting the legendary figure as the Wandering (or Eternal) Jew or as

''Wandering Jew and Jewess''

dramatic screenplays * * David Hoffman, Hon. J.U.D. of Gottegen (1852).

Chronicles of the Wandering Jew

selected from the originals of Carthaphilus, embracing a period of nearly XIX centuries''—detailed description of facts related to Jesus's preaching from a Pharisees coverage

''The (presumed) End of the Wandering Jew'' from ''The Golden Calf'' by Ilf and Petrov

Israel's First President, Chaim Weizmann, "A Wandering Jew"

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

"The Wandering Image: Converting the Wandering Jew" Iconography and visual art.

"The Wandering Jew" and "The Wandering Jew's Chronicle"

English Broadside Ballad Archive * Full text:

[Alternative format]

{{authority control Fictional characters introduced in the 13th century Fictional immortals Legendary Jews Curses Antisemitic tropes Christian folklore Medieval legends Mythological characters European folklore Shoemakers

calque

In linguistics, a calque () or loan translation is a word or phrase borrowed from another language by literal word-for-word or root-for-root translation. When used as a verb, "to calque" means to borrow a word or phrase from another language ...

from German ) is a mythical immortal man whose legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human values, and possess certain qualities that give the ...

began to spread in Europe in the 13th century. In the original legend, a Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

who taunted Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

on the way to the Crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the condemned is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross, beam or stake and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by the Achaemenid Empire, Persians, Ancient Carthag ...

was then cursed to walk the Earth until the Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is the Christianity, Christian and Islam, Islamic belief that Jesus, Jesus Christ will return to Earth after his Ascension of Jesus, ascension to Heaven (Christianity), Heav ...

. The exact nature of the wanderer's indiscretion varies in different versions of the tale, as do aspects of his character; sometimes he is said to be a shoemaker

Shoemaking is the process of making footwear.

Originally, shoes were made one at a time by hand, often by groups of shoemakers, or '' cordwainers'' (sometimes misidentified as cobblers, who repair shoes rather than make them). In the 18th cen ...

or other tradesman

A tradesperson or tradesman/tradeswoman is a skilled worker that specialises in a particular trade. Tradespeople (tradesmen/women) usually gain their skills through work experience, on-the-job training, an apprenticeship program or formal educ ...

, while sometimes he is the doorman at the estate of Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate (; ) was the Roman administration of Judaea (AD 6–135), fifth governor of the Judaea (Roman province), Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor Tiberius from 26/27 to 36/37 AD. He is best known for being the official wh ...

.

Name

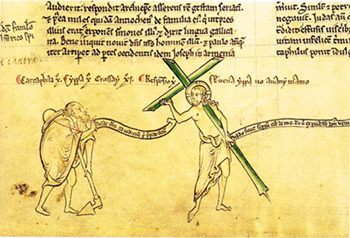

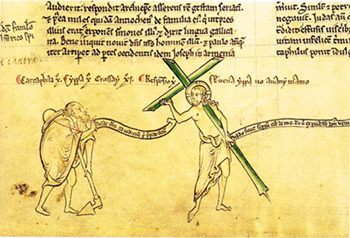

An early extant manuscript containing the legend is the ''Flores Historiarum

The ''Flores Historiarum'' (Flowers of History) is the name of two different (though related) Latin chronicles by medieval English historians that were created in the 13th century, associated originally with the Abbey of St Albans.

Wendover's ...

'' by Roger of Wendover

Roger of Wendover (died 6 May 1236), probably a native of Wendover in Buckinghamshire, was an English chronicler of the 13th century.

At an uncertain date he became a monk at St Albans Abbey; afterwards he was appointed prior of the cell ...

, where it appears in the part for the year 1228, under the title ''Of the Jew Joseph who is still alive awaiting the last coming of Christ''. The central figure is named ''Cartaphilus'' before being baptized later by Ananias as ''Joseph''. The root of the name ''Cartaphilus'' can be divided into and , which can be translated roughly as "dearly" and "loved", connecting the legend of the Wandering Jew to "the disciple whom Jesus loved

The phrase "the disciple whom Jesus loved" () or, in John 20:2; "the other disciple whom Jesus loved" (), is used six times in the Gospel of John, but in no other New Testament accounts of Jesus. John 21:24 states that the Gospel of John is base ...

".

At least from the 17th century, the name ''Ahasver'' has been given to the Wandering Jew, apparently adapted from Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus ( ; , commonly ''Achashverosh''; , in the Septuagint; in the Vulgate) is a name applied in the Hebrew Bible to three rulers of Ancient Persia and to a Babylonian official (or Median king) first appearing in the Tanakh in the Book of ...

(Xerxes), the Persian king in the Book of Esther

The Book of Esther (; ; ), also known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as "the Scroll" ("the wikt:מגילה, Megillah"), is a book in the third section (, "Writings") of the Hebrew Bible. It is one of the Five Megillot, Five Scrolls () in the Hebr ...

, who was not a Jew, and whose very name among medieval Jews was an of a fool. This name may have been chosen because the Book of Esther describes the Jews as a persecuted people, scattered across every province of Ahasuerus' vast empire, similar to the later Jewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora ( ), alternatively the dispersion ( ) or the exile ( ; ), consists of Jews who reside outside of the Land of Israel. Historically, it refers to the expansive scattering of the Israelites out of their homeland in the Southe ...

in countries whose state and/or majority religions were forms of Christianity.

A variety of names have since been given to the Wandering Jew, including ''Matathias'', ''Buttadeus'' and ''Isaac Laquedem'', which is a name for him in France and the

A variety of names have since been given to the Wandering Jew, including ''Matathias'', ''Buttadeus'' and ''Isaac Laquedem'', which is a name for him in France and the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

in popular legend as well as in a novel by Dumas. The name ''Paul Marrane'' (an anglicized version of Giovanni Paolo Marana

Giovanni Paolo Marana or sometimes Jean-Paul Marana (1642 – 1693) was a writer of both fiction and non-fiction, best remembered for his conviction for failing to reveal a conspiracy to cede the Genoese town of Savona to the Duchy of Savoy.

Bio ...

, the alleged author of ''Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy

''Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy'' () is an eight-volume collection of fictional letters claiming to have been written by an Ottoman spy named "Mahmut", in the French court of Louis XIV.

Authorship and publication

It is agreed that the first vol ...

'') was incorrectly attributed to the Wandering Jew by a 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' article, yet the mistake influenced popular culture. The name given to the Wandering Jew in the spy's Letters is ''Michob Ader''.

The name ''Buttadeus'' (''Botadeo'' in Italian; ''Boutedieu'' in French) most likely has its origin in a combination of the Vulgar Latin version of ("to beat or strike") with the word for God, . Sometimes this name is misinterpreted as ''Votadeo'', meaning "devoted to God", drawing similarities to the etymology of the name ''Cartaphilus''.

Where German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

or Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

is spoken, the emphasis has been on the perpetual character of his punishment, and thus he is known there as and (), the "Eternal Jew". In French and other Romance languages

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are Language family, directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-E ...

, the usage has been to refer to the wanderings, as in (French), (Spanish) or (Italian), and this has been followed in English from the Middle Ages as the ''Wandering Jew''. In Finnish, he is known as ("Shoemaker of Jerusalem"), implying he was a cobbler

Cobbler(s) may refer to:

*A person who repairs shoes

* Cobbler (food), a type of pie

Places

* The Cobbler, a mountain located near the head of Loch Long in Scotland

* Mount Cobbler, Australia

Art, entertainment and media

* ''The Cobbler' ...

by his trade. In Hungarian, he is known as the ("Wandering Jew" but with a connotation of aimlessness).

Origin and evolution

Biblical sources

The origins of the legend are uncertain; perhaps one element is the story inGenesis

Genesis may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of humankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Bo ...

of Cain

Cain is a biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He is the elder brother of Abel, and the firstborn son of Adam and Eve, the first couple within the Bible. He was a farmer who gave an offering of his crops to God. How ...

, who is issued with a similar punishment—to wander the Earth, scavenging and never reaping, although without the related punishment of endlessness. According to Jehoshua Gilboa, many commentators have pointed to Hosea 9:17 as a statement of the notion of the "eternal/wandering Jew". The legend stems from Jesus' words given in Matthew 16:28:

A belief that the disciple whom Jesus loved

The phrase "the disciple whom Jesus loved" () or, in John 20:2; "the other disciple whom Jesus loved" (), is used six times in the Gospel of John, but in no other New Testament accounts of Jesus. John 21:24 states that the Gospel of John is base ...

would not die was apparently popular enough in the early Christian world to be denounced in the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John () is the fourth of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "Book of Signs, signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the ...

:

Another passage in the Gospel of John speaks about a guard of the high priest who slaps Jesus (John 18:19–23). Earlier, the Gospel of John talks about Simon Peter striking the ear from Malchus, a servant of the high priest (John 18:10). Although this servant is probably not the same guard who struck Jesus, Malchus is nonetheless one of the many names given to the wandering Jew in later legend.

Early Christianity

The later amalgamation of the fate of the specific figure of legend with the condition of the Jewish people as a whole, well established by the 18th century, had its precursor even in early Christian views of Jews and the diaspora. Extant manuscripts have shown that as early as the time of

The later amalgamation of the fate of the specific figure of legend with the condition of the Jewish people as a whole, well established by the 18th century, had its precursor even in early Christian views of Jews and the diaspora. Extant manuscripts have shown that as early as the time of Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

(), some Christian proponents were likening the Jewish people to a "new Cain", asserting that they would be "fugitives and wanderers (upon) the earth".

Aurelius Prudentius Clemens

Aurelius Prudentius Clemens () was a Roman Christian poet, born in the Roman province of Tarraconensis (now Northern Spain) in 348.H. J. Rose, ''A Handbook of Classical Literature'' (1967) p. 508 He probably died in the Iberian Peninsula some tim ...

(b. 348) writes in his ''Apotheosis'' (c. 400): "From place to place the homeless Jew wanders in ever-shifting exile, since the time when he was torn from the abode of his fathers and has been suffering the penalty for murder, and having stained his hands with the blood of Christ whom he denied, paying the price of sin."

A late 6th and early 7th century monk named Johannes Moschos records an important version of a Malchean figure. In his '' Leimonarion'', Moschos recounts meeting a monk named Isidor who had purportedly met a Malchus-type of figure who struck Christ and is therefore punished to wander in eternal suffering and lament:

Medieval legend

Some scholars have identified components of the legend of the Eternal Jew in Teutonic legends of the Eternal Hunter, some features of which are derived fromOdin

Odin (; from ) is a widely revered god in Norse mythology and Germanic paganism. Most surviving information on Odin comes from Norse mythology, but he figures prominently in the recorded history of Northern Europe. This includes the Roman Em ...

mythology.

"In some areas the farmers arranged the rows in their fields in such a way that on Sundays the Eternal Jew might find a resting place. Elsewhere they assumed that he could rest only upon a plough or that he had to be on the go all year and was allowed a respite only on Christmas."

Most likely drawing on centuries of unwritten folklore, legendry, and oral tradition brought to the West as a product of the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

, a Latin chronicle from Bologna, , contains the first written articulation of the Wandering Jew. In the entry for the year 1223, the chronicle describes the report of a group of pilgrims who meet "a certain Jew in Armenia" () who scolded Jesus on his way to be crucified and is therefore doomed to live until the Second Coming. Every hundred years the Jew returns to the age of 30.

A variant of the Wandering Jew legend is recorded in the by Roger of Wendover

Roger of Wendover (died 6 May 1236), probably a native of Wendover in Buckinghamshire, was an English chronicler of the 13th century.

At an uncertain date he became a monk at St Albans Abbey; afterwards he was appointed prior of the cell ...

around the year 1228. An Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

n archbishop, then visiting England, was asked by the monks of St Albans Abbey

St Albans Cathedral, officially the Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Alban, also known as "the Abbey", is a Church of England cathedral in St Albans, England.

Much of its architecture dates from Norman times. It ceased to be an abbey follo ...

about the celebrated Joseph of Arimathea

Joseph of Arimathea () is a Biblical figure who assumed responsibility for the burial of Jesus after Crucifixion of Jesus, his crucifixion. Three of the four Biblical Canon, canonical Gospels identify him as a member of the Sanhedrin, while the ...

, who had spoken to Jesus, and was reported to be still alive. The archbishop answered that he had himself seen such a man in Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

, and that his name was Cartaphilus, a Jewish shoemaker, who, when Jesus stopped for a second to rest while carrying his cross, hit him, and told him "Go on quicker, Jesus! Go on quicker! Why dost Thou loiter?", to which Jesus, "with a stern countenance", is said to have replied: "I shall stand and rest, but thou shalt go on till the last day." The Armenian bishop also reported that Cartaphilus had since converted to Christianity and spent his wandering days proselytizing

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Carrying out attempts to instill beliefs can be called proselytization.

Proselytism is illegal in some countries. Some draw distinctions between Chris ...

and leading a hermit

A hermit, also known as an eremite (adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

In Christianity, the term was originally applied to a Chr ...

's life.

Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris (; 1200 – 1259), was an English people, English Benedictine monk, English historians in the Middle Ages, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts, and cartographer who was based at St A ...

included this passage from Roger of Wendover in his own history; and other Armenians appeared in 1252 at the Abbey of St Albans, repeating the same story, which was regarded there as a great proof of the truth of the Christian religion. The same Armenian told the story at Tournai

Tournai ( , ; ; ; , sometimes Anglicisation (linguistics), anglicised in older sources as "Tournay") is a city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia located in the Hainaut Province, Province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies by ...

in 1243, according to the ''Chronicles of Phillip Mouskes'' (chapter ii. 491, Brussels, 1839). After that, Guido Bonatti

Guido Bonatti (died between 1296 and 1300) was an Italian mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems. Mathematicians are concerned with n ...

writes people saw the Wandering Jew in Forlì

Forlì ( ; ; ; ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) and city in Emilia-Romagna, Northern Italy, and is, together with Cesena, the capital of the Province of Forlì-Cesena.The city is situated along the Via Emilia, to the east of the Montone river, ...

(Italy), in the 13th century; other people saw him in Vienna and elsewhere.

There were claims of sightings of the Wandering Jew throughout Europe and later the Americas, since at least 1542 in Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

up to 1868 in Harts Corners, New Jersey. Joseph Jacobs

Joseph Jacobs (29 August 1854 – 30 January 1916) was an Australian-born folklorist, literary critic and historian who became a notable collector and publisher of English folklore.

Born in Sydney to a Jewish family, his work went on to popula ...

, writing in the 11th edition of the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (1911), commented, "It is difficult to tell in any one of these cases how far the story is an entire fiction and how far some ingenious impostor took advantage of the existence of the myth".

Another legend about Jews, the so-called "Red Jews

The Red Jews (), a legendary Jewish nation, appear in vernacular sources in Germany during the medieval era, from the 13th to the 15th centuries. These texts portray the Red Jews as an epochal threat to Christendom, one which would invade Europ ...

", was similarly common in Central Europe in the Middle Ages.

In literature

17th and 18th centuries

The legend became more popular after it appeared in a 17th-century pamphlet of four leaves, (''Short Description and Tale of a Jew with the Name Ahasuerus''). "Here we are told that some fifty years before, a bishop met him in a church at Hamburg, repentant, ill-clothed and distracted at the thought of having to move on in a few weeks." As withurban legend

Urban legend (sometimes modern legend, urban myth, or simply legend) is a genre of folklore concerning stories about an unusual (usually scary) or humorous event that many people believe to be true but largely are not.

These legends can be e ...

s, particularities lend verisimilitude: the bishop is specifically Paulus von Eitzen, General Superintendent of Schleswig. The legend spread quickly throughout Germany, no less than eight different editions appearing in 1602; altogether forty appeared in Germany before the end of the 18th century. Eight editions in Dutch and Flemish are known; and the story soon passed to France, the first French edition appearing in Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

, 1609, and to England, where it appeared in the form of a parody in 1625. The pamphlet was translated also into Danish and Swedish; and the expression "eternal Jew" is current in Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

, Slovak, and German, . Apparently the pamphlets of 1602 borrowed parts of the descriptions of the wanderer from reports (most notably by Balthasar Russow

Balthasar Russow (1536–1600) was one of the most important Livonian and Estonian chroniclers.

Russow was born in Reval, Livonia (now Tallinn, Estonia). He was educated at an academy in Stettin, Pomerania (now Szczecin, Poland). He was the Lut ...

) about an itinerant preacher called Jürgen.

In France, the Wandering Jew appeared in Simon Tyssot de Patot

Simon Tyssot de Patot (1655–1738) was a French writer and poet during the Age of Enlightenment who penned two very important, seminal works in fantastic literature. Tyssot was born in London of French Huguenot parents. He was brought up in Roua ...

's (1720).

In Britain, a ballad with the title ''The Wandering Jew'' was included in Thomas Percy's '' Reliques'' published in 1765.

In England, the Wandering Jew makes an appearance in one of the secondary plots in Matthew Lewis's Gothic novel ''The Monk

''The Monk: A Romance'' is a Gothic novel by Matthew Gregory Lewis, published in 1796 across three volumes. Written early in Lewis's career, it was published anonymously when he was 20. It tells the story of a virtuous Catholic monk who give ...

'' (1796). The Wandering Jew is depicted as an exorcist whose origin remains unclear. The Wandering Jew also plays a role in '' St. Leon'' (1799) by William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. Godwin is most famous fo ...

. The Wandering Jew also appears in two English broadside ballad

A broadside (also known as a broadsheet) is a single sheet of inexpensive paper printed on one side, often with a ballad, rhyme, news and sometimes with woodcut illustrations. They were one of the most common forms of printed material between the ...

s of the 17th and 18th centuries, ''The Wandering Jew

The Wandering Jew (occasionally referred to as the Eternal Jew, a calque from German ) is a mythical Immortality, immortal man whose legend began to spread in Europe in the 13th century. In the original legend, a Jew who taunted Jesus on the way ...

'', and '' The Wandering Jew's Chronicle''. The former recounts the biblical story of the Wandering Jew's encounter with Christ, while the latter tells, from the point of view of the titular character, the succession of English monarchs from William the Conqueror through either King Charles II (in the 17th-century text) or King George II and Queen Caroline (in the 18th-century version).

In 1797, the operetta ''The Wandering Jew, or Love's Masquerade'' by Andrew Franklin was performed in London.

19th century

Britain

In 1810,Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Bysshe Shelley ( ; 4 August 1792 – 8 July 1822) was an English writer who is considered one of the major English Romantic poets. A radical in his poetry as well as in his political and social views, Shelley did not achieve fame durin ...

wrote a poem in four cantos with the title ''The Wandering Jew'' but it remained unpublished until 1877. In two other works of Shelley, Ahasuerus appears, as a phantom in his first major poem '' Queen Mab: A Philosophical Poem'' (1813) and later as a hermit healer in his last major work, the verse drama '' Hellas''.

John Galt published a book in 1820 called ''The Wandering Jew''.

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

, in his ''Sartor Resartus

''Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books'' is a novel by the Scottish people, Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, first published as a serial in ''Fraser's Magazine'' in November 1833 ...

'' (1833–34), compares its hero Diogenes Teufelsdröckh on several occasions to the Wandering Jew (also using the German wording ).

In Chapter 15 of ''Great Expectations

''Great Expectations'' is the thirteenth novel by English author Charles Dickens and his penultimate completed novel. The novel is a bildungsroman and depicts the education of an orphan nicknamed Pip. It is Dickens' second novel, after ''Dav ...

'' (1861) by Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

, the journeyman Orlick is compared to the Wandering Jew.

George MacDonald

George MacDonald (10 December 1824 – 18 September 1905) was a Scottish author, poet and Christian Congregational minister. He became a pioneering figure in the field of modern fantasy literature and the mentor of fellow-writer Lewis Carrol ...

includes pieces of the legend in ''Thomas Wingfold, Curate'' (London, 1876).

United States

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (né Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associat ...

's stories "A Virtuoso's Collection" and "Ethan Brand" feature the Wandering Jew serving as a guide to the stories' characters.Brian Stableford

Brian Michael Stableford (25 July 1948 – 24 February 2024) was a British academic, critic and science fiction writer who published a hundred novels and over a hundred volumes of translations. His earlier books were published under the name Br ...

, "Introduction" to ''Tales of the Wandering Jew'' edited by Stableford. Dedalus, Sawtry, 1991. . pp. 1–25.

In 1873, a publisher in the United States (Philadelphia, Gebbie) produced ''The Legend of the Wandering Jew, a series of twelve designs by Gustave Doré

Paul Gustave Louis Christophe Doré ( , , ; 6January 1832 – 23January 1883) was a French printmaker, illustrator, painter, comics artist, caricaturist, and sculptor. He is best known for his prolific output of wood-engravings illustrati ...

(Reproduced by Photographic Printing) with Explanatory Introduction'', originally made by Doré in 1856 to illustrate a short poem by Pierre-Jean de Béranger

Pierre-Jean de Béranger (; 19 August 1780 – 16 July 1857) was a prolific France, French poet and Chansonnier (singer), chansonnier (songwriter), who enjoyed great popularity and influence in France during his lifetime, but faded into obscurity ...

. For each one, there was a couplet, such as "Too late he feels, by look, and deed, and word, / How often he has crucified his Lord".

Eugene Field

Eugene Field Sr. (September 2, 1850 – November 4, 1895) was an American writer, best known for his children's poetry and humorous essays. He was known as the "poet of childhood".

Early life and education

Field was born in St. Louis, Missouri ...

's short story "The Holy Cross" (1899) features the Jew as a character.

In 1901, a New York publisher reprinted, under the title "Tarry Thou Till I Come", George Croly's "Salathiel", which treated the subject in an imaginative form. It had appeared anonymously in 1828.

In Lew Wallace

Lewis Wallace (April 10, 1827February 15, 1905) was an American lawyer, Union general in the American Civil War, governor of New Mexico Territory, politician, diplomat, artist, and author from Indiana. Among his novels and biographies, Walla ...

's novel ''The Prince of India'' (1893), the Wandering Jew is the protagonist. The book follows his adventures through the ages, as he takes part in the shaping of history. An American rabbi, H. M. Bien, turned the character into the "Wandering Gentile" in his novel ''Ben-Beor: A Tale of the Anti-Messiah''; in the same year John L. McKeever wrote a novel, ''The Wandering Jew: A Tale of the Lost Tribes of Israel''.

A humorous account of the Wandering Jew appears in chapter 54 of Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

's 1869 travel book

Travel is the movement of people between distant geographical locations. Travel can be done by foot, bicycle, automobile, train, boat, bus, airplane, ship or other means, with or without luggage, and can be one way or round trip. Travel ca ...

''The Innocents Abroad

''The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrim's Progress'' is a travel book by American author Mark Twain. Published in 1869, it humorously chronicles what Twain called his "Great Pleasure Excursion" on board the chartered steamship ''Quaker City' ...

''.

Germany

The legend has been the subject of Germanpoem

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

s by Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart

Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart (24 March 1739 – 10 October 1791) was a German poet, organist, composer, and journalist. He was repeatedly punished for his social-critical writing and spent ten years in severe conditions in jail.

Life

Born ...

, , Wilhelm Müller

Johann Ludwig Wilhelm Müller (7 October 1794 – 30 September 1827) was a German lyric poet, best known as the author of ''Die schöne Müllerin'' (1821) and ''Winterreise'' (1823). These would later be the source of inspiration for two song cy ...

, Nikolaus Lenau

Nikolaus Lenau was the pen name of Nikolaus Franz Niembsch Edler von Strehlenau (13 August 1802 – 22 August 1850), a German-language Austrian poet.

Biography

He was born at Csatád (Schadat), Kingdom of Hungary, now Lenauheim, Banat, then p ...

, Adelbert von Chamisso

Adelbert von Chamisso (; 30 January 1781 – 21 August 1838) was a German poet, writer and botanist. He was commonly known in French as Adelbert de Chamisso (or Chamissot) de Boncourt, a name referring to the family estate at Boncourt.

Life

...

, August Wilhelm von Schlegel, Julius Mosen (an epic, 1838), and Ludwig Köhler; of novel

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The word derives from the for 'new', 'news', or 'short story (of something new)', itself from the , a singular noun use of the neuter plural of ...

s by Franz Horn

Franz Horn (26 August 1904 – 22 September 1963) was a German international footballer. He was part of Germany's team at the 1928 Summer Olympics

The 1928 Summer Olympics (), officially the Games of the IX Olympiad (), was an international ...

(1818), , and Levin Schücking

Levin Schücking (full name: ''Christoph Bernhard Levin Matthias Schücking''; September 6, 1814 – August 31, 1883) was a German novelist. He was born near Meppen, Kingdom of Prussia, and died in Bad Pyrmont, German Empire. He was the uncle of ...

; and of tragedies

A tragedy is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character or cast of characters. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy is to invoke an accompanying catharsis, or a "pain ...

by Ernst August Friedrich Klingemann ("", 1827) and Joseph Christian Freiherr von Zedlitz (1844). It is either the Ahasuerus of Klingemann or that of Achim von Arnim

Carl Joachim Friedrich Ludwig von Arnim (26 January 1781 – 21 January 1831), better known as Achim von Arnim, was a German poet, novelist, and together with Clemens Brentano and Joseph von Eichendorff, a leading figure of German Romanticism.

...

in his play, ', to whom Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

refers in the final passage of his notorious essay .

There are clear echoes of the Wandering Jew in Wagner's '' The Flying Dutchman'', whose plot line is adapted from a story by Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; ; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was an outstanding poet, writer, and literary criticism, literary critic of 19th-century German Romanticism. He is best known outside Germany for his ...

in which the Dutchman is referred to as "the Wandering Jew of the ocean", and his final opera features a woman called Kundry who is in some ways a female version of the Wandering Jew. It is alleged that she was formerly Herodias

Herodias (; , ''Hērōidiás''; c. 15 BC – after AD 39) was a princess of the Herodian dynasty of Judea, Judaea during the time of the Roman Empire. Christian writings connect her with the Beheading of John the Baptist, execution of John the Ba ...

, and she admits that she laughed at Jesus on his route to the Crucifixion, and is now condemned to wander until she meets with him again (cf. Eugene Sue's version, below).

Robert Hamerling, in his (Vienna, 1866), identifies Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

with the Wandering Jew. Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

had designed a poem on the subject, the plot of which he sketched in his .

Denmark

Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen ( , ; 2 April 1805 – 4 August 1875) was a Danish author. Although a prolific writer of plays, travelogue (literature), travelogues, novels, and poems, he is best remembered for his literary fairy tales.

Andersen's fai ...

made his "Ahasuerus" the Angel of Doubt, and was imitated by Heller in a poem on "The Wandering of Ahasuerus", which he afterward developed into three cantos. Martin Andersen Nexø

Martin Andersen Nexø (26 June 1869 – 1 June 1954) was a Danish writer. He was one of the authors in the Modern Breakthrough movement in Danish art and literature. He was a socialist throughout his life and during the Second World War moved ...

wrote a short story named "The Eternal Jew", in which he also refers to Ahasuerus as the spreading of the Jewish gene pool in Europe.

The story of the Wandering Jew is the basis of the essay "The Unhappiest One" in Søren Kierkegaard

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard ( , ; ; 5 May 1813 – 11 November 1855) was a Danes, Danish theologian, philosopher, poet, social critic, and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher. He wrote critical tex ...

's '' Either/Or'' (published 1843 in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

). It is also discussed in an early portion of the book that focuses on Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition and proficiency from an early age ...

's opera ''Don Giovanni

''Don Giovanni'' (; K. 527; full title: , literally ''The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni'') is an opera in two acts with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an Italian libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte. Its subject is a centuries-old Spanish legen ...

''.

In the play (''The Residents'') by Jens Christian Hostrup

Jens Christian Hostrup (20 May 1818 in Copenhagen – 21 November 1892 in Frederiksberg) was a Danish poet, dramatist and priest. Comforting and encouraging the people, he created poems that filled the hearts of his compatriots. His precise pers ...

(1844), the Wandering Jew is a character (in this context called "Jerusalem's shoemaker") and his shoes make the wearer invisible. The protagonist of the play borrows the shoes for a night and visits the house across the street as an invisible man.

France

The French writerEdgar Quinet

Edgar Quinet (; 17 February 180327 March 1875) was a French historian and intellectual.

Biography

Early years

Quinet was born at Bourg-en-Bresse, in the ''département'' of Ain. His father, Jérôme Quinet, had been a commissary in the army, ...

published his prose epic on the legend in 1833, making the subject the judgment of the world; and wrote his in 1844, in which the author connects the story of Ahasuerus with that of Herodias

Herodias (; , ''Hērōidiás''; c. 15 BC – after AD 39) was a princess of the Herodian dynasty of Judea, Judaea during the time of the Roman Empire. Christian writings connect her with the Beheading of John the Baptist, execution of John the Ba ...

. Grenier's 1857 poem on the subject may have been inspired by 's designs, which were published the preceding year. One should also note 's (1864), which combines several fictional Wandering Jews, both heroic and evil, and Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (born Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas , was a French novelist and playwright.

His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the mos ...

' incomplete (1853), a sprawling historical saga. In Guy de Maupassant's short story "Uncle Judas", the local people believe that the old man in the story is the Wandering Jew.

In the late 1830's, the epic novel "The Wandering Jew," written by Eugene Sue was published in serialized form.

Russia

In Russia, the legend of the Wandering Jew appears in an incomplete epic poem byVasily Zhukovsky

Vasily Andreyevich Zhukovsky (; – ) was the foremost Russian poet of the 1810s and a leading figure in Russian literature in the first half of the 19th century. He held a high position at the Romanov court as tutor to the Grand Duchess Alexan ...

, "Ahasuerus" (1857) and in another epic poem by Wilhelm Küchelbecker

Wilhelm Ludwig von Küchelbecker (; in St. Petersburg – in Tobolsk) was a Russian Romantic poet and Decembrist revolutionary of German descent.

Life

Born into a Baltic German noble family, he spent his childhood in what is now Estonia a ...

, "Ahasuerus, a Poem in Fragments", written between 1832 and 1846 but not published until 1878, long after the poet's death. Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

also began a long poem on Ahasuerus (1826) but later abandoned the project, completing fewer than thirty lines.

Other literature

The Wandering Jew makes a notable appearance in the gothic masterpiece of thePolish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

writer Jan Potocki

Count Jan Potocki (; 8 March 1761 – 23 December 1815) was a Polish nobleman, ethnologist, linguist, traveller and author of the Enlightenment period, whose life and exploits made him a celebrated figure in Poland. He is known chiefly for his ...

, ''The Manuscript Found in Saragossa

''The Manuscript Found in Saragossa'' (; also known in English as ''The Saragossa Manuscript'') is a frame tale, frame-tale novel written in French language, French at the turn of 18th and 19th centuries by the Poland, Polish author Count Jan Pot ...

'', written about 1797.

Brazilian writer and poet Machado de Assis

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (), often known by his surnames as Machado de Assis, ''Machado,'' or ''Bruxo do Cosme Velho''Vainfas, p. 505. (21 June 1839 – 29 September 1908), was a pioneer Brazilian people, Brazilian novelist, poet, playwr ...

often used Jewish themes in his writings. One of his short stories, ("To Live!"), is a dialog between the Wandering Jew (named as Ahasverus) and Prometheus

In Greek mythology, Prometheus (; , , possibly meaning "forethought")Smith"Prometheus". is a Titans, Titan. He is best known for defying the Olympian gods by taking theft of fire, fire from them and giving it to humanity in the form of technol ...

at the end of time. It was published in 1896 as part of the book (''Several stories'').

Castro Alves

Antônio Frederico de Castro Alves (14 March 1847 – 6 July 1871) was a Brazilian poet and playwright famous for his abolitionist and republican poems. One of the most famous poets of the Condorist movement, he wrote classics such as '' Esp ...

, another Brazilian poet, wrote a poem named "" ("Ahasverus and the genie"), in a reference to the Wandering Jew.

The Hungarian poet János Arany

János Arany (; archaic English: John Arany; 2 March 1817 – 22 October 1882) was a Hungarian poet, writer, translator and journalist. He is often said to be the "Shakespeare of ballads" – he wrote more than 102 ballads that have been transl ...

also wrote a ballad called ("The Eternal Jew").

The Slovenian poet Anton Aškerc

Anton Aškerc (; 9 January 1856 – 10 June 1912) was a Slovenian poet and Roman Catholic priest who worked in Austria, best known for his epic poems.

Aškerc was born into a peasant family near the town of Rimske Toplice in the Duchy of Styria, ...

wrote a poem called ("Ahasverus' Temple").

The Spanish military writer José Gómez de Arteche's novel (''A Spanish soldier of twenty centuries'') (1874–1886) depicts the Wandering Jew as serving in the Spanish military of different periods.

20th century

Latin America

In Mexican writerMariano Azuela

Mariano Azuela González (January 1, 1873 – March 1, 1952) was a Mexican writer and medical doctor, best known for his fictional stories of the Mexican Revolution of 1910. He wrote novels, works for theatre and literary criticism. He is t ...

's 1920 novel set during the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

, '' The Underdogs'' (), the character Venancio, a semi-educated barber, entertains the band of revolutionaries by recounting episodes from ''The Wandering Jew'', one of two books he had read.

In Argentina, the topic of the Wandering Jew has appeared several times in the work of Enrique Anderson Imbert

Enrique Anderson-Imbert (February 12, 1910– December 6, 2000) was an Argentine novelist, short-story writer and literary critic.

Born in Córdoba, Argentina, the son of Jose Enrique Anderson and Honorina Imbert, Anderson-Imbert graduated from t ...

, particularly in his short-story (''The Grimoire''), included in the eponymous book.

Chapter XXXVII, , in the collection of short stories, , by the Argentine writer Manuel Mujica Láinez also centres round the wandering of the Jew.

The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo ( ; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator regarded as a key figure in Spanish literature, Spanish-language and international literatur ...

named the main character and narrator of his short story "The Immortal" Joseph Cartaphilus (in the story he was a Roman military tribune who gained immortality after drinking from a magical river and dies in the 1920s).

In ''Green Mansions

''Green Mansions: A Romance of the Tropical Forest'' is a 1904 exotic romance by William Henry Hudson about a traveller to the Guyana jungle of southeastern Venezuela and his encounter with a forest-dwelling girl named Rima.

The principal ...

'', W. H. Hudson's protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a ...

Abel references Ahasuerus

Ahasuerus ( ; , commonly ''Achashverosh''; , in the Septuagint; in the Vulgate) is a name applied in the Hebrew Bible to three rulers of Ancient Persia and to a Babylonian official (or Median king) first appearing in the Tanakh in the Book of ...

, as an archetype of someone, like himself, who prays for redemption and peace, while condemned to walk the earth.

In 1967, the Wandering Jew appears as an unexplained magical realist townfolk legend in Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel José García Márquez (; 6 March 1927 – 17 April 2014) was a Colombian writer and journalist, known affectionately as Gabo () or Gabito () throughout Latin America. Considered one of the most significant authors of the 20th centur ...

's ''One Hundred Years of Solitude

''One Hundred Years of Solitude'' (, ) is a 1967 in literature, 1967 novel by Colombian people, Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez that tells the Family saga, multi-generational story of the Buendía family, whose patriarch, José Arcadio ...

''. In his short story, “One Day After Saturday,” the character Father Anthony Isabel claims to encounter the Wandering Jew again in the mythical town of Macondo.

Colombian writer Prospero Morales Pradilla, in his novel (''The sins of Ines de Hinojosa''), describes the famous Wandering Jew of Tunja that has been there since the 16th century. He talks about the wooden statue of the Wandering Jew that is in Santo Domingo church and every year during the holy week is carried around on the shoulders of the Easter penitents around the city. The main feature of the statue are his eyes; they can express the hatred and anger in front of Jesus carrying the cross.

Brazil

In 1970, Polish-Brazilian writer Samuel Rawet published ("Travels of Ahasverus to foreign lands in search of a past that does not exist because it is a future and a future that has already passed because it was dreamed"), a short story in which the main character, Ahasverus, or The Wandering Jew, is capable of transforming into various other figures.France

Guillaume Apollinaire

Guillaume Apollinaire (; ; born Kostrowicki; 26 August 1880 – 9 November 1918) was a French poet, playwright, short story writer, novelist and art critic of Poland, Polish descent.

Apollinaire is considered one of the foremost poets of the ...

parodies the character in in his

collection (''Heresiarch & Co.'', 1910).

Jean d'Ormesson wow in (1991).

In Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 – 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, nor was she ...

's novel (''All Men are Mortal'', 1946), the leading figure Raymond Fosca undergoes a fate similar to the wandering Jew, who is explicitly mentioned as a reference.

Germany

In bothGustav Meyrink

Gustav Meyrink (19 January 1868 – 4 December 1932) was the pseudonym of Gustav Meyer, an Austrian author,

novelist, dramatist, translator, and banker, most famous for his novel ''The Golem (Meyrink novel), The Golem''.

He has been described as ...

's ''The Green Face'' (1916) and Leo Perutz's ''The Marquis of Bolibar'' (1920), the Wandering Jew features as a central character.

The German writer Stefan Heym

Helmut Flieg (10 April 1913 – 16 December 2001) was a German writer, known by his pseudonym Stefan Heym (). He lived in the United States and trained at Camp Ritchie in 1943, making him one of the Ritchie Boys of World War II. In 1952, he r ...

in his novel (translated into English as ''The Wandering Jew'') maps a story of Ahasuerus and Lucifer

The most common meaning for Lucifer in English is as a name for the Devil in Christian theology.

He appeared in the King James Version of the Bible in Isaiah and before that in the Vulgate (the late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bib ...

ranging between ancient times, the Germany of Luther and socialist East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

. In Heym's depiction, the Wandering Jew is a highly sympathetic character.

Belgium

The Belgian writerAugust Vermeylen

August Vermeylen (12 May 1872, in Brussels – 10 January 1945, in Uccle) was a Belgium, Belgian writer and literature critic. In 1893 he founded the literary journal ''Van Nu en Straks'' (''Of Today and Tomorrow''). He studied history at the Fre ...

published in 1906 a novel called (''The Wandering Jew'').

Romania

Mihai Eminescu

Mihai Eminescu (; born Mihail Eminovici; 15 January 1850 – 15 June 1889) was a Romanians, Romanian Romanticism, Romantic poet, novelist, and journalist from Moldavia, generally regarded as the most famous and influential Romanian poet. Emin ...

, an influential Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

Romantic writer, depicts a variation in his 1872 fantasy novella Poor Dionysus (). A student named Dionis goes on a surreal journey through the book of Zoroaster

Zarathushtra Spitama, more commonly known as Zoroaster or Zarathustra, was an Iranian peoples, Iranian religious reformer who challenged the tenets of the contemporary Ancient Iranian religion, becoming the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism ...

, which seemingly grants him godlike abilities. The book is given to him by Ruben, his Jewish master who is a philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

. Dionis awakens as Friar Dan, and is eventually tricked by Ruben, being sentenced by God to a life of insanity. This he can only escape by resurrection

Resurrection or anastasis is the concept of coming back to life after death. Reincarnation is a similar process hypothesized by other religions involving the same person or deity returning to another body. The disappearance of a body is anothe ...

or metempsychosis

In philosophy and theology, metempsychosis () is the transmigration of the soul, especially its reincarnation after death. The term is derived from ancient Greek philosophy, and has been recontextualized by modern philosophers such as Arthur Sc ...

.

Similarly, Mircea Eliade

Mircea Eliade (; – April 22, 1986) was a Romanian History of religion, historian of religion, fiction writer, philosopher, and professor at the University of Chicago. One of the most influential scholars of religion of the 20th century and in ...

presents in his novel

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The word derives from the for 'new', 'news', or 'short story (of something new)', itself from the , a singular noun use of the neuter plural of ...

''Dayan'' (1979) a student's mystic and fantastic journey through time and space under the guidance of the Wandering Jew, in the search of a higher truth and of his own self.

Russia

The Sovietsatirists

This is an incomplete list of writers, cartoonists and others known for involvement in satire – humorous social criticism. They are grouped by era and listed by year of birth. Included is a list of modern satires.

Early satirical authors

*Aeso ...

Ilya Ilf

Ilya Arnoldovich Ilf (born Iehiel-Leyb Aryevich Faynzilberg; ; – 13 April 1937) was a Soviet journalist and writer of Jewish origin who usually worked in collaboration with Yevgeny Petrov during the 1920s and 1930s. Their duo was known simp ...

and Yevgeni Petrov had their hero Ostap Bender

Ostap Bender () is a fictional confidence trick, con man and the central antiheroic protagonist in the novels ''The Twelve Chairs'' (1928) and ''The Little Golden Calf'' (1931) written by Soviet authors Ilya Ilf Ilf and Petrov, and Yevgeny Petrov ...

tell the story of the Wandering Jew's death at the hands of Ukrainian nationalists in ''The Little Golden Calf

''The Little Golden Calf'' (, ''Zolotoy telyonok'') is a satirical picaresque novel by Soviet authors Ilf and Petrov, published in 1931. Its main character, Ostap Bender, also appears in a previous novel by the authors called ''The Twelve Chairs ...

''. In Vsevolod Ivanov's story ''Ahasver'' a strange man comes to a Soviet writer in Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

in 1944, introduces himself as "Ahasver the cosmopolite" and claims he is Paul von Eitzen, a theologian from Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

, who concocted the legend of the Wandering Jew in the 16th century to become rich and famous but then turned himself into a real Ahasver against his will. The novel ''Overburdened with Evil'' (1988) by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky

The brothers Arkady Strugatsky (28 August 1925 – 12 October 1991) and Boris Strugatsky (14 April 1933 – 19 November 2012) were Soviet and Russian science-fiction authors who collaborated through most of their careers. Their notable works in ...

involves a character in modern setting who turns out to be Ahasuerus, identified at the same time in a subplot with John the Divine. In the novel ''Going to the Light'' (, 1998) by Sergey Golosovsky, Ahasuerus turns out to be Apostle Paul

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

, punished (together with Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

and Mohammed

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monotheistic teachings of Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, ...

) for inventing false religion.

South Korea

The 1979 Korean novel ''Son of Man'' by Yi Mun-yol (introduced and translated into English by Brother Anthony, 2015), is framed within a detective story. It describes the character of Ahasuerus as a defender of humanity against unreasonable laws of the Jewish god, Yahweh. This leads to his confrontations with Jesus and withholding of aid to Jesus on the way to Calvary. The unpublished manuscript of the novel was written by a disillusioned theology student, Min Yoseop, who has been murdered. The text of the manuscript provides clues to solving the murder. There are strong parallels between Min Yoseop and Ahasuerus, both of whom are consumed by their philosophical ideals.Sweden

InPär Lagerkvist

Pär Fabian Lagerkvist (23 May 1891 – 11 July 1974) was a Swedish author who received the 1951 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Lagerkvist wrote poetry, plays, novels, short stories, and essays of considerable expressive power and influence from hi ...

's 1956 novel ''The Sibyl'', Ahasuerus and a woman who was once the Delphic Sibyl

The Delphic Sibyl was a prophetess associated with early religious practices in Ancient Greece and is said to have been venerated from before the Trojan Wars as an important oracle. At that time Delphi was a place of worship for Gaia, the mother ...

each tell their stories, describing how an interaction with the divine damaged their lives. Lagerkvist continued the story of Ahasuerus in (''The Death of Ahasuerus'', 1960).

Ukraine

In Ukrainian legend, there is a character of Marko Pekelnyi (Marko of Hell, Marko the Infernal) or Marko the Accursed. This character is based on the archetype of the Wandering Jew. The origin of Marko's image is also rooted in the legend of the traitor Mark, who struck Christ with an iron glove before his death on the cross, for which God punished him by forcing him to eternally walk underground around a pillar, not stopping even for a minute; he bangs his head against a pillar from time to time, disturbs even hell and its master with these sounds and complains that he cannot die. Another explanation for Mark's curse is that he fell in love with his own sister, then killed her along with his mother, for which he was punished by God. Ukrainian authors Oleksa Storozhenko,Lina Kostenko

Lina Vasylivna Kostenko (; born 19 March 1930) is a Ukrainian poet, journalist, writer, publisher, and former Soviet dissident. A founder and leading representative of the Sixtiers poetry movement, Kostenko has been described as one of Ukrai ...

, Ivan Malkovych

Ivan Antonovych Malkovych (; born 10 May 1961 in Nyzhnii Bereziv, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, Ivano-Frankivsk) is a noted Ukrainians, Ukrainian poet and publisher. He is the proprietor of the publishing house "A-ba-ba-ha-la-ma-ha, A-BA-BA-HA-LA-MA-HA" ...

and others have written prose and poetry about Marko the Infernal. Also, Les Kurbas Theatre made a stage performance "Marko the Infernal, or the Easter Legend" based on the poetry of Vasyl Stus

Vasyl Semenovych Stus (; January 6, 1938 – September 4, 1985) was a Ukrainian poet, translator, literary critic, journalist, and an active member of the Ukrainian dissident movement. For his political convictions, his works were banned by th ...

.

United Kingdom

Bernard Capes' story "The Accursed Cordonnier" (1900) depicts the Wandering Jew as a figure of menace. Robert Nichols' novella "Golgotha & Co." in his collection ''Fantastica'' (1923) is a satirical tale where the Wandering Jew is a successful businessman who subverts theSecond Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is the Christianity, Christian and Islam, Islamic belief that Jesus, Jesus Christ will return to Earth after his Ascension of Jesus, ascension to Heaven (Christianity), Heav ...

.

In Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires ''Decli ...

's ''Helena'', the Wandering Jew appears in a dream to the protagonist and shows her where to look for the Cross, the goal of her quest.

J. G. Ballard

James Graham Ballard (15 November 193019 April 2009) was an English novelist and short-story writer, satirist and essayist known for psychologically provocative works of fiction that explore the relations between human psychology, technology, s ...

's short story "The Lost Leonardo", published in '' The Terminal Beach'' (1964), centres on a search for the Wandering Jew. The Wandering Jew is revealed to be Judas Ischariot, who is so obsessed with all known depictions of the crucifixion that he travels all around the world to steal them from collectors and museums, replacing them with forged duplicates. The story's first German translation, published the same year as the English original, translates the story's title as ''Wanderer durch Zeit und Raum'' ("Wanderer through Time and Space"), directly referencing the concept of the "eternally Wandering" Jew.

The horror novel ''Devil Daddy'' (1972) by John Blackburn features the Wandering Jew.

The Wandering Jew appears as a sympathetic character in Diana Wynne Jones

Diana Wynne Jones (16 August 1934 – 26 March 2011) was a British novelist, poet, academic, literary critic, and short story writer. She principally wrote fantasy and speculative fiction novels for children and young adults. Although usually d ...

's young adult novel '' The Homeward Bounders'' (1981). His fate is tied in with larger plot themes regarding destiny, disobedience, and punishment.

In Ian McDonald's 1991 story ''Fragments of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria'' (originally published in ''Tales of the Wandering Jew'', ed. Brian Stableford

Brian Michael Stableford (25 July 1948 – 24 February 2024) was a British academic, critic and science fiction writer who published a hundred novels and over a hundred volumes of translations. His earlier books were published under the name Br ...

), the Wandering Jew first violates and traumatizes a little girl during the Edwardian era

In the United Kingdom, the Edwardian era was a period in the early 20th century that spanned the reign of King Edward VII from 1901 to 1910. It is commonly extended to the start of the First World War in 1914, during the early reign of King Ge ...

, where her violation is denied and explained away by Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

analyzing her and coming to the erroneous conclusion that her signs of abuse are actually due to a case of hysteria or prudishness. A quarter of a century later, the Wandering Jew takes on the guise of a gentile éminence grise

An ''éminence grise'' () or gray eminence is a powerful decisionmaker or advisor who operates covertly in a nonpublic or unofficial capacity.

The original French phrase referred to François Leclerc du Tremblay, the right hand man of Cardina ...

who works out the genocidal ideology and bureaucracy of the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

and secretly incites the Germans into carrying it out according to his plans. In a meeting with one of the victims where he's gloatingly telling her that she and millions of others will die, he reveals that he did it out of self-hatred.

United States

InO. Henry

William Sydney Porter (September 11, 1862 – June 5, 1910), better known by his pen name O. Henry, was an American writer known primarily for his short stories, though he also wrote poetry and non-fiction. His works include "The Gift of the Ma ...

's 1911 story "The Door of Unrest", a drunk shoemaker Mike O'Bader comes to a local newspaper editor and claims to be the Jerusalem shoemaker Michob Ader who did not let Christ rest upon his doorstep on the way to crucifixion and was condemned to live until the Second Coming. However, Mike O'Bader insists he is a Gentile

''Gentile'' () is a word that today usually means someone who is not Jewish. Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, have historically used the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is used as a synony ...

, not a Jew.

"The Wandering Jew" is the title of a short poem by Edwin Arlington Robinson

Edwin Arlington Robinson (December 22, 1869 – April 6, 1935) was an American poet and playwright. Robinson won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry on three occasions and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature four times.

Early life

Robins ...

which appears in his 1920 book ''The Three Taverns''. In the poem, the speaker encounters a mysterious figure with eyes that "remembered everything". He recognizes him from "his image when I was a child" and finds him to be bitter, with "a ringing wealth of old anathemas"; a man for whom the "world around him was a gift of anguish". The speaker does not know what became of him, but believes that "somewhere among men to-day / Those old, unyielding eyes may flash / And flinch—and look the other way."

George Sylvester Viereck

George Sylvester Viereck (December 31, 1884 – March 18, 1962) was an American poet and journalist. After enjoying early success for his poetry, novels, and journalistic work, he achieved notoriety in the United States as a pro-German propagandi ...

and Paul Eldridge wrote a trilogy of novels ''My First Two Thousand Years: an Autobiography of the Wandering Jew'' (1928), in which Isaac Laquedem is a Roman soldier who, after being told by Jesus that he will "tarry until I return", goes on to influence many of the great events of history. He frequently encounters Solome (described as "The Wandering Jewess"), and travels with a companion, to whom he has passed on his immortality via a blood transfusion (another attempt to do this for a woman he loved ended in her death).

"Ahasver", a cult leader identified with the Wandering Jew, is a central figure in Anthony Boucher

William Anthony Parker White (August 21, 1911 – April 29, 1968), better known by his pen name Anthony Boucher (), was an American author, critic, and editor who wrote several classic mystery novels, short stories, science fiction, and radio dr ...

's classic mystery novel ''Nine Times Nine'' (originally published 1940 under the name H. Holmes).

Written by Isaac Asimov in October 1956, the short story " Does a Bee Care?" features a highly influential character named Kane who is stated to have spawned the legends of the Walking Jew and the Flying Dutchman in his thousands of years maturing on Earth, guiding humanity toward the creation of technology which would allow it to return to its far-distant home in another solar system. The story originally appeared in the June 1957 edition of ''If: Worlds of Science Fiction'' magazine and is collected in the anthology ''Buy Jupiter and Other Stories'' (Isaac Asimov, Doubleday Science Fiction, 1975).

A Jewish Wanderer appears in ''A Canticle for Leibowitz

''A Canticle for Leibowitz'' is a post-apocalyptic social science fiction novel by American writer Walter M. Miller Jr., first published in 1959. Set in a Catholic monastery in the desert of the southwestern United States after a devastating ...

'', a post-apocalyptic

Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction are genres of speculative fiction in which the Earth's (or another planet's) civilization is collapsing or has collapsed. The apocalypse event may be climatic, such as runaway climate change; astronom ...

science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may include information technology and robotics, biological manipulations, space ...

novel by Walter M. Miller, Jr. first published in 1960; some children are heard saying of the old man, "What Jesus raises up STAYS raised up", and introduces himself in Hebrew as Lazarus, implying that he is Lazarus of Bethany

Lazarus of Bethany is a figure of the New Testament whose life is restored by Jesus four days after his death, as told in the Gospel of John. The resurrection is considered one of the miracles of Jesus. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, Lazarus i ...

, whom Christ raised from the dead. Another possibility hinted at in the novel is that this character is also Isaac Edward Leibowitz, founder of the (fictional) Albertian Order of St. Leibowitz (and who was martyred for trying to preserve books from burning by a savage mob). The character speaks and writes in Hebrew and English, and wanders around the desert, though he has a tent on a mesa

A mesa is an isolated, flat-topped elevation, ridge, or hill, bounded from all sides by steep escarpments and standing distinctly above a surrounding plain. Mesas consist of flat-lying soft sedimentary rocks, such as shales, capped by a ...

overlooking the abbey founded by Leibowitz, which is the setting for almost all the novel's action. The character appears again in three subsequent novellas which take place hundreds of years apart, and in Miller's 1997 follow-up novel, '' Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman''.

Ahasuerus must remain on Earth after space travel is developed in Lester del Rey

Lester del Rey (June 2, 1915 – May 10, 1993) was an American science fiction author and editor. He was the author of many books in the juvenile Winston Science Fiction series, and the fantasy editor at Del Rey Books, the fantasy an ...

's "Earthbound" (1963). The Wandering Jew also appears in Mary Elizabeth Counselman's story "A Handful of Silver" (1967). Barry Sadler

Barry Allen Sadler (November 1, 1940 – November 5, 1989) was an American singer-songwriter and author whose military service influenced his work. After a stint in the United States Air Force, Sadler served in the United States Army as a Uni ...

has written a series of books featuring a character called Casca Rufio Longinus who is a combination of two characters from Christian folklore, Saint Longinus

Longinus (Greek: Λογγίνος) is the name of the Roman soldier who pierced the side of Jesus with a lance, who in apostolic and some modern Christian traditions is described as a convert to Christianity. His name first appeared in the apoc ...

and the Wandering Jew. Jack L. Chalker wrote a five-book series called ''The Well World

''Well World'' is a series of science fiction novels by Jack L. Chalker. It involves a planet-sized supercomputer known as the Well of Souls that builds reality on top of an underlying one of greater complexity but smaller size. The computer wa ...

Saga'' in which it is mentioned many times that the creator of the universe, a man named Nathan Brazil, is known as the Wandering Jew. The 10th issue of DC Comics

DC Comics (originally DC Comics, Inc., and also known simply as DC) is an American comic book publisher owned by DC Entertainment, a subsidiary of Warner Bros. Discovery. DC is an initialism for "Detective Comics", an American comic book seri ...

' ''Secret Origins

''Secret Origins'' is the title of several comic book series published by DC Comics which featured the origin stories of the publisher's various characters.

Publication history

''Secret Origins'' was first published as a one-shot in 1961 and c ...

'' (January 1987) gave The Phantom Stranger four possible origins. In one of these explanations, the Stranger confirms to a priest that he is the Wandering Jew. Angela Hunt's novel ''The Immortal'' (2000) features the Wandering Jew under the name of Asher Genzano.

Although he does not appear in Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein ( ; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific acc ...

's novel ''Time Enough for Love

''Time Enough for Love'' is a science fiction novel by American writer Robert A. Heinlein, first published in 1973. The book made the shortlist for the Nebula, Hugo and Locus awards for best science fiction novel of that year, although it did no ...

'' (1973), the central character, Lazarus Long

Lazarus Long is a fictional character featured in a number of science fiction novels by American writer Robert A. Heinlein. Born in 1912 in the third generation of a selective breeding experiment run by the Ira Howard Foundation, Lazarus (birth ...

, claims to have encountered the Wandering Jew at least once, possibly multiple times, over the course of his long life. According to Lazarus, he was then using the name Sandy Macdougal and was operating as a con man

A scam, or a confidence trick, is an attempt to defraud a person or group after first gaining their trust. Confidence tricks exploit victims using a combination of the victim's credulity, naivety, compassion, vanity, confidence, irresponsibi ...

. He is described as having red hair and being, in Lazarus' words, a "crashing bore".

The Wandering Jew is revealed to be Judas Iscariot

Judas Iscariot (; ; died AD) was, according to Christianity's four canonical gospels, one of the original Twelve Apostles of Jesus Christ. Judas betrayed Jesus to the Sanhedrin in the Garden of Gethsemane, in exchange for thirty pieces of sil ...

in George R. R. Martin

George Raymond Richard Martin (born George Raymond Martin; September 20, 1948) also known by the initials G.R.R.M. is an American author, television writer, and television producer. He is best known as the author of the unfinished series of Hi ...

's distant-future science fiction parable of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...