African socialism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

African socialism is a distinct variant of socialist theory developed in post-colonial Africa during the mid-20th century. As a shared ideological project among several African thinkers over the decades, it encompasses a variety of competing interpretations. However, a consistent and defining theme among these theories is the notion that traditional African cultures and community structures have a natural inclination toward socialist principles.

This characterization of socialism as an indigenous African tradition sets African socialism apart as a unique ideological movement, distinctly separate from other socialist movements on the continent or elsewhere in the world. Prominent contributors to this field include

In 1967, President Julius Nyerere of the newly-unified Tanzania issued the Arusha Declaration, committing Tanzania to a socialist reform program. At the center of these reforms was ''

In 1967, President Julius Nyerere of the newly-unified Tanzania issued the Arusha Declaration, committing Tanzania to a socialist reform program. At the center of these reforms was ''http://www.jstor.org/stable/43905075 .

Nyerere’s government has also garnered criticism for the manner in which Ujamaa was implemented. At the outset of the program, Ujamaa was to be a voluntary, decentralized effort, leaving a certain degree of autonomy to the individual villages. Over time, however, the state assumed a degree of control over village management and production that some historians have labeled coercive and autocratic, claiming this contradicted the democratic values Ujamaa espoused.

The failure of Ujamaa to deliver on its promises of development and equality led to a wave of intense backlash in the late 1970s-80s. In 1981, the Tanzanian government committed to its “National Economic Survival Programme”, a set of policy changes designed to liberalize the economy. Nyerere stepped down from the Presidency in 1985, but continued to advocate for his model of socialism until his death. By the end of his political tenure, 96% of children had gone to primary school, 50% of them being girls. Female life expectancy had grown from 41 to 50.7 years between 1960 and 1980 and maternal mortality rates dropped from 450 per 100,000 births to under 200 by 1973. Posthumously, Nyerere and Ujamaa have seen a resurgence in popularity in Tanzania.

Professor Ivan Potekhin

argued that African Socialism could not exist because there could be no varieties of true Marxist–Leninist socialism. There was not one monolith perspective on whether

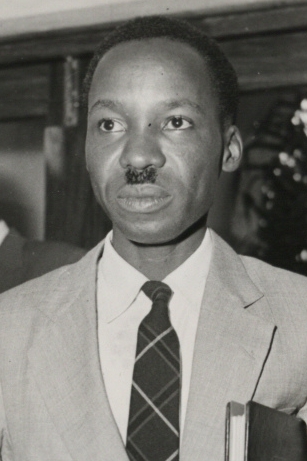

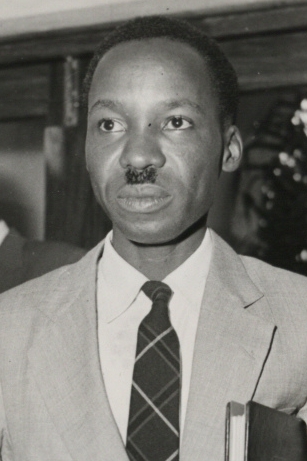

Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian politician, anti-colonial activist, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika (1961–1964), Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as presid ...

of Tanzania, Kwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

of Ghana, and Léopold Sédar Senghor

Léopold Sédar Senghor ( , , ; 9 October 1906 – 20 December 2001) was a Senegalese politician, cultural theorist and poet who served as the first president of Senegal from 1960 to 1980.

Ideologically an African socialist, Senghor was one ...

of Senegal.

Origins and themes

As many African countries gained independence during the 1960s, some of these newly formed governments rejected the ideas of capitalism in favour of a more afrocentric economic model. Leaders of this period professed that they were practising "African socialism".Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian politician, anti-colonial activist, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika (1961–1964), Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as presid ...

of Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

, Modibo Keita of Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

, Léopold Senghor of Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

, Joseph Saidu Momoh and Siaka Stevens

Siaka Probyn Stevens (24 August 1905 – 29 May 1988) was the leader of Sierra Leone from 1967 to 1985, serving as Prime Minister from 1967 to 1971 and as President from 1971 to 1985. Stevens' leadership was often characterized by patrimonial ...

in Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

, Kwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

and Hilla Limann

Hilla Limann, (12 December 1934 – 23 January 1998) was a Ghanaian diplomat and politician who served as the eighth president of Ghana from 1979 to 1981. He previously served as a diplomat in Lomé and in Geneva.

Education

Limann, whose origi ...

of Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

, François Tombalbaye in Chad

Chad, officially the Republic of Chad, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of North Africa, North and Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to Chad–Libya border, the north, Sudan to Chad–Sudan border, the east, the Central Afric ...

, Modibo Keïta in Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

, Sékou Touré of Guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

, and Luís Cabral in Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau, officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau, is a country in West Africa that covers with an estimated population of 2,026,778. It borders Senegal to Guinea-Bissau–Senegal border, its north and Guinea to Guinea–Guinea-Bissau b ...

were the main architects of African Socialism, according to William H. Friedland and Carl G. Rosberg Jr., editors of the book ''African Socialism''.

Common principles of various versions of African socialism were social development guided by a large public sector, an emphasis on an African identity and what it means to be African, and the preservation or revival of a classless society. Senghor claimed that "Africa’s social background of tribal community life not only makes socialism natural to Africa but excludes the validity of the theory of class struggle," thus making African socialism, in all of its variations, different from Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

and European socialist theory.

African socialism became an important model of economic development for countries such as Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

, Guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

, Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

and Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

. While these countries used different models of African Socialism, many commonalities emerged, such as the desire for political and economic autonomy, self reliance, the Africanisation of business and civil service, Pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atla ...

and non-alignment.

The first influential publication of socialist thought tailored for application in Africa occurred in 1956 with the release of Senegalese intellectual Abdoulaye Ly's ''Les masses africaines et l'actuelle condition humaine''.

History and Variants

Julius Nyerere and Ujamaa

In 1967, President Julius Nyerere of the newly-unified Tanzania issued the Arusha Declaration, committing Tanzania to a socialist reform program. At the center of these reforms was ''

In 1967, President Julius Nyerere of the newly-unified Tanzania issued the Arusha Declaration, committing Tanzania to a socialist reform program. At the center of these reforms was ''Ujamaa

Ujamaa ( in Swahili language, Swahili) was a Socialism, socialist ideology that formed the basis of Julius Nyerere's social and economic Economic development, development policies in Tanzania after it gained independence from Britain in 1961.

Mor ...

''. Ujamaa, meaning "familyhood" in Swahili, was Julius Nyerere's framework for African socialism, intended to integrate traditional communal values with modern ideas of economic and social development.

Though his ideas bear similarities to other forms of socialism in Europe and Asia, Nyerere made it clear through his writings that he saw Ujamaa as distinct from the broader Marxist tradition. Rather than focusing on class struggle, Nyerere imagined the goal of socialism in Tanzania (and Africa generally) to be the restoration of the pre-colonial family unit. As members of a larger familial network, individuals were expected to support each other and share work, lessons that Nyerere believed laid the groundwork for a socialist education. Ujamaa was not meant to replace a failing capitalist system, like socialism was seen in Marxist theory, but to deconstruct the artificial power structures imposed by colonial rule and return to a naturally socialist order.Bonny Ibhawoh and Jeremiah Dibua, "Deconstructing Ujamaa: The Legacy of Julius Nyerere in the Quest for Social and Economic Development in Africa," ''African Journal of Political Science 8, no. 1 (2003): 69.''

The ideal society, according to Nyerere, would be built around the core principles of “freedom, equality, and unity”; together, these tenets would create an economy based on cooperative production, foster peaceful community bonds, and encourage democratic political participation. From 1968-1975, Nyerere’s government facilitated the consolidation of rural Tanzania into village-style agricultural communities where resources would be shared collectively. Nyerere, wary of the influence of Western-controlled international economic institutions, claimed that true liberation from colonialism required Tanzania to be economically self-sufficient. These farming villages were to serve as the heart of that development, building Tanzania’s economy while also freeing its culture from the capitalist value and power structure imposed under colonial rule. The theoretical link that Ujamaa created between economic development and social liberation has been praised for being ahead of its time, anticipating a framework that would not become mainstream in Western sociology until the late 20th century.Leander Schneider, "Freedom and Unfreedom in Rural Development: Julius Nyerere, Ujamaa Vijijini, and Villagization," ''Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne des Études Africaines'' 38, no. 2 (2004): 358.

The general international consensus on the Ujamaa policy regime is that it failed to live up to its goals. Most of the communities created under the Ujamaa program were unable to become self-sufficient in the way Nyerere had imagined. The accelerated timeline on which the reforms were executed and bureaucratic inefficiencies gave way to disappointing economic results. Though the goal of the Ujamaa villagization was to create economic production centers, much of Tanzania’s agricultural production was still done on independently owned small-scale farms that had not been absorbed into the state system.Brian Van Arkadie, ''Economic Strategy and Structural Adjustment in Tanzania,'' PSD Occasional Paper No. 18, The World Bank, 1995. The forced collectivization of farmland that had once been family-owned was a sore point for many farmers, who bristled at the radical cultural and lifestyle changes they were expected to embrace; meanwhile, in cities, the state's focus on agricultural production had inhibited its ability to address socioeconomic class division in urban environments.Marie-Aude Fouéré, “Julius Nyerere, Ujamaa, and Political Morality in Contemporary Tanzania.” ''African Studies Review'' 57, no. 1 (2014): 1–24. Ubuntu

The ancientUbuntu philosophy

Ubuntu (; meaning in some Bantu languages, such as Zulu language, Zulu) describes a set of closely related Bantu African-origin value systems that emphasize the interconnectedness of individuals with their surrounding societal and physical world ...

of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

recognizes the humanity of a person through their interpersonal relationships. The word comes from the Zulu and Xhosa languages. Ubuntu believes in a bond that ties together all of humanity and the fact that a human being is of a high value. According to Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (7 October 193126 December 2021) was a South African Anglican bishop and theologian, known for his work as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist. He was Bishop of Johannesburg from 1985 to 1986 and then Archbishop o ...

, A man with ubuntu is open and accessible to others, confirming of others, doesn't feel debilitated that others are capable and great, for he or she has a legitimate confidence that originates from realizing that he or she has a place in a more noteworthy entire and is decreased when others are mortified or reduced, when others are tormented or abused.

Harambee

''Harambee

Harambee is a Kenyan tradition of community self-help events, e.g. fundraising or development activities. The word means "all pull together" in Swahili language, Swahili, and is the official List of national mottos, motto of Kenya, appearing on ...

'' is a term that originated among natives, specifically Swahili porters of East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

; the word ''harambee'' traditionally means "let us pull together". It was taken as an opportunity for local Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

ns to self-develop their communities without waiting on government. This helped build a sense of togetherness in the Kenyan community but analysts state that it has brought about class discrepancies because some individuals use this as an opportunity to generate wealth.

Kwame Nkrumah and Nkrumahism

Nkrumahism was the political philosophy ofGhana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

's first post-independence president Kwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

. As one of the first African political leaders, Nkrumah became a major figure in the left-wing pan-African

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the Trans-Sa ...

movement. In his piece ''A declaration to the colonial peoples'', Nkrumah called on Africans to "...affirm the right of all colonial peoples to control their own destiny." and that "All colonies must be free from foreign imperialist control, whether political or economic.". His focus on economic and political freedom would prove to be a fundamental part of his overarching political philosophy, combining the nationalist independence movement in his home country of Ghana along with left-wing economic thought.

A major figure in the Ghanaian independence movement, Nkrumah came to power shortly after Ghana gained its independence in 1957. Once in power, he began a series of infrastructural and economic development plans designed to stimulate the Ghanaian economy. $16 million was designated to be used to build a new town in Tema

Tema is a city on the Bight of Benin and Atlantic coast of Ghana. It is located east of the capital city; Accra, in the region of Greater Accra, and is the capital of the Tema Metropolitan District. As of 2013, Tema is the eleventh most p ...

to be used as an open seaport for Accra and the eastern region of the country. The government designed a new plan to tackle issues surrounding illiteracy and lack of access to education, with thousands of new schools being built in rural areas.

Determined to industrialize the country rapidly, Nkrumah set out to modernize Ghana's economy in order to better compete with the West. In turn, his government embarked on a strategy of slowly increasing the amount of government-controlled firms in the country while simultaneously putting restrictions on privately owned companies operating in Ghana. By 1965, the state-controlled 50% of the insurance industry within the country, 60% of all bank deposits were deposited at state-run banks, 17% of the country's sea-bound cargo was handled by state-run firms, 27% of all industrial production was either produced by state-run firms or firms in which the state-controlled a considerable portion and 35% of the country's total imports were handled by the government.

Nkrumah also pushed for Ghana to become an international advocate for the spread of socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

and pan-Africanism throughout the newly independent African states. As the first African colonial state to be granted independence, Ghana became an inspiration to many of the nascent left-wing independence movements throughout the continent. In 1958, Nkrumah helped found the Union of Independent African States, a political union between Ghana, Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

, and Guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

. Though the union was short-lived, the proposed political organization marked the first attempt at regional unity among newly established African republics.

Nkrumah was also instrumental in pushing Ghana towards the major Communist powers, including the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and the PRC

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the second-most populous country after India, representing 17.4% of the world population. China spans the e ...

. In 1961, he made his first official visit to Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, receiving an honorary degree from the University of Moscow. In a speech given in Accra

Accra (; or ''Gaga''; ; Ewe: Gɛ; ) is the capital and largest city of Ghana, located on the southern coast at the Gulf of Guinea, which is part of the Atlantic Ocean. As of 2021 census, the Accra Metropolitan District, , had a population of ...

in front of a visiting Soviet delegation in 1963, Nkrumah said, "We in Ghana have formally chosen the socialist path and we will build a socialist society... Thus our countries, the Soviet Union and Ghana, will go forward together."

Nkrumah also used the Eastern bloc to expand Ghana's economy by establishing state owned enterprises. In 1962, a Ghanaian newspaper reported that out of the sixty-three foreign agreements signed in 1961, forty-four of the agreements were with East European countries focusing on trade, payments and scientific, technical, and cultural co-operation. There were also five agreements with China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

and another five with Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

.

Léopold Sédar Senghor and the Socialist Party of Senegal

Léopold Senghor was the founder of the Socialist Party of Senegal and the first President of the country. An important figure not only in the political development of the country, but Senghor was also one of the leading figures in theNégritude

''Négritude'' (from French "nègre" and "-itude" to denote a condition that can be translated as "Blackness") is a framework of critique and literary theory, mainly developed by francophone intellectuals, writers, and politicians in the Africa ...

movement, which informed much of his political thought. Senghor would come to embody a new form of African socialism that rejected many of the traditional Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

modes of thinking that had developed in post-independence Africa.

Born into an upper-middle-class family, Senghor was able to take advantage of the French educational system that was afforded to many of Africa's educated colonial elite. However, these schools did little to teach African students about their native culture, instead favoring policies of assimilation into mainstream French life. As Senghor once put it the French wanted "bread for all, culture for all, liberty for all; but this liberty, this culture, and this bread will be French." Excelling in his primary education, Senghor enrolled in the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

.

After graduating and serving in the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Senghor began a career as a poet in Paris, releasing his first book, ''Chants d'ombre (Shadow Songs) '' in 1945 and ''Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malagache de langue française (Anthology of the New Black and Malagasy Poetry)'' in 1948. Both pieces were instrumental in developing the bulk of the emerging Négritude movement, which Senghor hoped would represent the "sum total of the values of the civilization of the African world.".

His work highlighted the vast inequalities in French colonial society and looked at the unique experience of the thousands of Africans living under French rule. In his piece ''The Challenge of Culture in French West Africa'', Senghor called on Africans to "develop a culture based on the strengths of local tradition that was also open to the modern European world".

Senghor was initially not a supporter of an independent Senegal, worrying that the small African country would have little chance as an independent nation. Instead, he advocated for an interconnected relationship similar to that of Paris and France's provinces. In his piece, ''Vues sure l'Afrique noir, ou s'assimiler non être assimilés (Views on Black Africa, or To Assimilate, Not Be Assimilated)'', Senghor advocated for popularly elected Senegalese representatives and an executive in Paris, French economic funds to help with Senegalese development, and the inclusion of African cultural and linguistic education in the French educational system.

In 1958, referendums were held in all of the French African colonies on the future of the colonial possessions. The debate was between full on independence and joining the French community

The French Community () was the constitutional organization set up in October 1958 between France and its remaining African colonies, then in the process of decolonization. It replaced the French Union, which had reorganized the colonial em ...

, a sort of association of former French colonies that would allow countries like Senegal to become independent, but still maintain an economic and diplomatic relations with the French government. Senghor supported the yes side of the vote and Senegal voted 97% in favor of the association.

When Senegal became a fully independent country in 1960, Senghor was elected to the presidency

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified b ...

. After a failed coup led by his Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

in 1962, the Senghor government moved to abolish the post, which was approved by 99% in referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

. The vote substantially strengthened the power of the President, who no longer had to compete with the Prime Minister for executive power.

The Socialist Party compounded its control of Senegalese politics in 1966 when it was declared the country's only legal party, with Senghor as its leader. The one-party system would stay in place until Senghor decided to liberalize the country's election laws by allowing for a 3 party system, with one socialist, one liberal, and one communist party being allowed to contest elections.

As president, Senghor represented a moderated version of African Socialism that didn't align with the more radical interpretations seen in other newly independent African states. Unlike other ex-colonies, Senegal remained closely aligned with the French government. They retained the French Franc as the national currency and Senghor was known to consult the French government before making any major foreign policy decisions. He allowed French advisors and companies to remain in Senegal, including in government and educational posts. When asked about nationalizing French companies, Senghor responded that it would be to "kill the goose that laid the golden egg". His government invested heavily in both education and the public sector, investing 12-15 billion francs and 6 to 9 billion francs in both sectors respectively. He also sought to give more power to the underdeveloped Senegalese countryside which he did by instituting price protections on peanut crops and allowing for rural representation when making decisions on agricultural policy.

Women and African socialism

African socialism proved to have mixed results for participating women. While some improvements were made from pre-developmental periods in the quality of life for women under African Socialism, setbacks and reflections of past gender hierarchies still persisted. In Ghana, newfound independence did not create a restructuring of old gender roles. Households were the building blocks of agricultural production and were almost exclusively headed by male workers. Accrued resources were then disproportionately controlled by household heads, under the assumption that subordinate women did not have to do as much work. However, economic crises in the 1980s saw the women of agricultural households adopt new strategies for reviving local welfare, such as replacing imported products with local goods and migrant male labor with their own. The increased presence of these women in the socialist workforce elevated their position in the community and granted them a say in rural production. Groups of working women began receiving their own plots of land from community leaders, and their contributions became recognized under the rural basis of Ghanaian socialism. Nonetheless, women who were not granted land often had to beg or receive permission from male landowners such as husbands or fathers. Without access to this land, local wives and daughters could not collect wild bush fruits or shea nuts, both crucial to financial welfare. After the introduction ofUjamaa

Ujamaa ( in Swahili language, Swahili) was a Socialism, socialist ideology that formed the basis of Julius Nyerere's social and economic Economic development, development policies in Tanzania after it gained independence from Britain in 1961.

Mor ...

to Tanzanian life in the late 1960s, strict gender roles became commonplace and were celebrated as a pillar of nuclear family. Despite efforts of development policy to purge Tanzanian government of European influence, the reinforcement of the nuclear family and assignment of women to the role of domestic house-maker reflected the practice of Christian colonizers before them.

This was likely because newfound independence saw a political focus on stability in the early developmental stages of Tanzania's government. Urban, working-class men unsure of the new government were seen as the greatest threat to national stability, and were provided improved salaries and access to housing which bolstered their position as household heads, and pushed women further into reproductive labor roles. Many of the goals surrounding Tanzanian women's rights movements were nonetheless met, including improvements in education, employment, and political opportunities. Regardless, the slow but sure subversion of women's rights movements in Tanzania saw women pushed further back into households, and female governmental leaders deposed for a number of trivial offenses. Still, Tanzanian villagization

Villagization (sometimes also spelled ''villagisation'') is the usually compulsory resettlement of people into designated villages by government or military authorities.

Security

Villagization may be used as a tactic by a government or military ...

is recalled positively by many Tanzanian women, as it often provided the opportunity to live closer to kin, and commit to more stable marriage practices. Post WWII, pre-development economy had previously resulted in widespread serial monogamy, or the precarious and temporary marrying and remarrying which was seen more as a survival strategy than romantic or reproductive endeavor. After resolving the discomfort of villagization, many women found advantage in their placement. For many Tanzanians, the crux of detriment towards women's rights came with the structural adjustment of Ujamaa economic policies in the 1980s.

Across nearly all socialist states in Africa, women's participation in politics did not face much improvement. In Senegal, Policies such as the “''Code de la Famille''” promised improvements for women's legal protections, but represented a set of laws that women were more subjects to than authors of. In many cases, such reforms were only introduced because of lobbying by wives of well placed politicians. Symbolic representation via educated “''femmes phares''”, or beacon women, was introduced with the one party system, and a set of quotas for women's political participation in the 1980s. Still, both concessions were more a result of male political competition than progressive movements for women's rights. Even those women who were granted public office enjoyed little influence compared to male colleagues of similar position. These developments reflected the predicament faced by eastern European women who received positions in symbolic organs of communist puppet-states. Real political power seemed to flow from the “inner circle” of such states. Power which was visible to the public in African nations was typically held by heads of state who were able to dominate and retain their position in a political monopoly.

African conferences for national liberation and socialism saw great participation from feminist organizations, but very little attention given to feminist issues. Nonetheless, developments were made with the unity of eastern feminist groups, but discourse with their western counterparts. With socialism and anti-colonialism at the forefront of African feminist issues, the question of how male leaders would make economic development benefit all members of a household was paramount, but one that was not taken seriously in conferences. Instead, feminist organizations were forced to drive international change on their own, often starting with the double standards and hypocrisies that could be found in their relations with other feminist groups. While feminists in Egypt were criticized for undemocratic practices in their developing government, countries like Britain seemed to escape scrutiny for its imperialist tendencies and improper treatment of its territories.

Relations to the Soviet Union

In the early 1960s, at the height of theCold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

based Africanists grappled with the concept of African Socialism and its legitimacy within the Marxist–Leninist theory. Leading Soviet AfricanistProfessor Ivan Potekhin

argued that African Socialism could not exist because there could be no varieties of true Marxist–Leninist socialism. There was not one monolith perspective on whether

socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

existed in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

. It was commonly believed that Africa could have its unique road to socialism but not its own form.

Soviet African Specialists recognized countries such as Guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

, Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

, and Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

as closer to true Marxist–Leninist socialism. Ahmed Sékou Touré

Ahmed Sékou Touré (var. Sheku Turay or Ture; N'Ko: ; 9 January 1922 – 26 March 1984) was a Guinean political leader and African statesman who was the first president of Guinea from 1958 until his death in 1984. Touré was among the primary ...

(1961), Modibo Keïta (1963) and Kwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

(1962) were honored with Lenin Peace Prize

The International Lenin Peace Prize (, ''mezhdunarodnaya Leninskaya premiya mira)'' was a Soviet Union award named in honor of Vladimir Lenin. It was awarded by a panel appointed by the Soviet government, to notable individuals whom the panel ...

s. Countries such as Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

and Côte d'Ivoire

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire and officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital city of Yamoussoukro is located in the centre of the country, while its largest city and ...

were considered ‘reactionary

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

’ and prone to collaboration with the imperialist powers.

Policies that were generally viewed as favorable by the Soviets were: economic independence, the creation of a national monetary system

A monetary system is a system where a government manages money in a country's economy. Modern monetary systems usually consist of the national treasury, the mint, the central banks and commercial banks.

Commodity money system

A commodity mon ...

, a strong state sector economy, a state bank

In Australia and the United States, a state bank in a federated state is usually a financial institution that is chartered by the government of that state, as opposed to one regulated at the federal or national level.

In British English, the ter ...

, state control over export

An export in international trade is a good produced in one country that is sold into another country or a service provided in one country for a national or resident of another country. The seller of such goods or the service provider is a ...

s and transports, mutual assistance programs and common land ownership.

African Socialists argued in favor of a distinctive form of socialism because they believed that socialism had its roots in pre-colonial African society. According to them, African society was a classless society

A classless society is a society in which no one is born into a social class like in a class society. Distinctions of wealth, income, education, culture, or social network might arise and would only be determined by individual experience an ...

, characterized by a communal spirit and democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

on the basis of government through discussion and consensus. The main objective was to unite African people in this idealized image of the traditional pre-colonial society.

Soviet Africanists did not agree that African society had a traditional classless society.

See also

* Third Worldism *Pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atla ...

* Anarchism in Africa

*Socialism with Chinese characteristics

Socialism with Chinese characteristics (; ) is a set of political theories and policies of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that are seen by their proponents as representing Marxism adapted to Chinese circumstances.

The term was first establ ...

*Arab socialism

Arab socialism () is a political ideology based on the combination of pan-Arabism or Arab nationalism and socialism. The term "Arab socialism" was coined by Michel Aflaq, the principal founder of Ba'athism and the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Part ...

* Melanesian socialism

*Ubuntu

Ubuntu ( ) is a Linux distribution based on Debian and composed primarily of free and open-source software. Developed by the British company Canonical (company), Canonical and a community of contributors under a Meritocracy, meritocratic gover ...

* Uhuru Movement

*Ujamaa

Ujamaa ( in Swahili language, Swahili) was a Socialism, socialist ideology that formed the basis of Julius Nyerere's social and economic Economic development, development policies in Tanzania after it gained independence from Britain in 1961.

Mor ...

*Harambee

Harambee is a Kenyan tradition of community self-help events, e.g. fundraising or development activities. The word means "all pull together" in Swahili language, Swahili, and is the official List of national mottos, motto of Kenya, appearing on ...

* Third International Theory

* Sankarism

Notes

References

* Bismarck U. Mwansasu and Cranford Pratt, ''Towards Socialism in Tanzania'', University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1979. * Fenner Brockway, ''African Socialism'', The Bodley Head, London, 1963. * Ghita Jonescu and Ernest Gellner, ''Populism'', Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1969. * Ngau, P. M. (1987). Tensions in Empowerment: The Experience of the “Harambee” (Self-Help) Movement in Kenya. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 35(3), 523–538. *Ng’ethe, N. (1983). POLITICS, IDEOLOGY AND THE UNDERPRIVILEGED: THE ORIGINS AND NATURE OF THE HARAMBEE PHENOMENON IN KENYA. Journal of Eastern African Research & Development, 13, 150–170. * Paolo Andreocci, ''Democrazia, partito unico e populismo nel pensiero politico africano'', in ''Africa'', Rome, n. 2–3, 1969. * Peter Worsley, ''The Third World'', Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1964. * William H. Crawford and Carl G. Rosberg Jr., ''African Socialism'', Stanford University press, California, 1964. * Ngau, P. M. (1987). Tensions in Empowerment: The Experience of the “Harambee” (Self-Help) Movement in Kenya. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 35(3), 523–538. * Ng’ethe, N. (1983). POLITICS, IDEOLOGY AND THE UNDERPRIVILEGED: THE ORIGINS AND NATURE OF THE HARAMBEE PHENOMENON IN KENYA. Journal of Eastern African Research & Development, 13, 150–170. * Smith, J. H. (1992). eview of Review of The Harambee Movement in Kenya: Self-Help, Development and Education among the Kamba of Kitui District, by M. J. D. Hill The Journal of Modern African Studies, 30(4), 701–703. * Yves Bénot, ''Idélogies des Indepéndances africaines'', F. Maspero, Paris, 1969. * {{Authority control Politics of Africa African and Black nationalism Socialism in Africa Left-wing politics in Africa African philosophy