African Iron Age on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Iron metallurgy in Africa concerns the origin and development of

From the mid-1970s there were new claims for independent invention of iron smelting in central Niger and from 1994 to 1999 UNESCO funded an initiative "Les Routes du Fer en Afrique/The Iron Routes in Africa" to investigate the origins and spread of iron metallurgy in Africa. This funded both the conference on early iron in Africa and the Mediterranean and a volume, published by UNESCO, that generated some controversy because it included only authors sympathetic to the independent-invention view.

Two reviews of the evidence from the mid-2000s found technical flaws in the studies claiming independent invention, raising three major issues. The first was whether the material dated by radiocarbon was in secure archaeological association with iron-working residues. Many of the dates from Niger, for example, were on organic matter in potsherds that were lying on the ground surface together with iron objects. The second issue was the possible effect of "old carbon": wood or charcoal much older than the time at which iron was smelted. This is a particular problem in Niger, where the charred stumps of ancient trees are a potential source of charcoal, and have sometimes been misidentified as smelting furnaces. A third issue is the weaker precision of the radiocarbon method for dates between 800 and 400 BCE, attributable to irregular production of radiocarbon in the upper atmosphere. Unfortunately most radiocarbon dates for the initial spread of iron metallurgy in sub-Saharan Africa fall within this range.

Controversy flared again in 2007 with the publication of excavations by Étienne Zangato and colleagues in the Central African Republic. At Oboui they excavated an undated iron forge yielding eight consistent radiocarbon dates of 2000 BCE. This would make Oboui the oldest iron-working site in the world, and more than a thousand years older than any other dated evidence of iron in Central Africa. Opinion among African archaeologists is sharply divided. Some specialists accept this interpretation, but archaeologist Bernard Clist has argued that Oboui is a highly disturbed site, with older charcoal having been brought up to the level of the forge by the digging of pits into older levels. Clist also raised questions about the unusually good state of preservation of metallic iron from the site. However, archaeologists such as Craddock, Eggert, and Holl have argued that such disturbance or disruption is highly unlikely given the nature of the site. Additionally, Holl, regarding the state of preservation, argues that this observation was based on published illustrations representing a small unrepresentative number of atypically well-preserved objects selected for publication. At Gbabiri, also in the Central African Republic, Eggert has found evidence of an iron reduction furnace and blacksmith workshop with earliest dates of 896–773 BCE and 907–796 BCE respectively.

In north-central Burkina Faso, remains of an iron smelting furnace near Douroula was also dated to the 8th century BCE, leading to the creation of the Ancient Ferrous Metallurgy Sites of Burkina Faso World Heritage Site. In the

From the mid-1970s there were new claims for independent invention of iron smelting in central Niger and from 1994 to 1999 UNESCO funded an initiative "Les Routes du Fer en Afrique/The Iron Routes in Africa" to investigate the origins and spread of iron metallurgy in Africa. This funded both the conference on early iron in Africa and the Mediterranean and a volume, published by UNESCO, that generated some controversy because it included only authors sympathetic to the independent-invention view.

Two reviews of the evidence from the mid-2000s found technical flaws in the studies claiming independent invention, raising three major issues. The first was whether the material dated by radiocarbon was in secure archaeological association with iron-working residues. Many of the dates from Niger, for example, were on organic matter in potsherds that were lying on the ground surface together with iron objects. The second issue was the possible effect of "old carbon": wood or charcoal much older than the time at which iron was smelted. This is a particular problem in Niger, where the charred stumps of ancient trees are a potential source of charcoal, and have sometimes been misidentified as smelting furnaces. A third issue is the weaker precision of the radiocarbon method for dates between 800 and 400 BCE, attributable to irregular production of radiocarbon in the upper atmosphere. Unfortunately most radiocarbon dates for the initial spread of iron metallurgy in sub-Saharan Africa fall within this range.

Controversy flared again in 2007 with the publication of excavations by Étienne Zangato and colleagues in the Central African Republic. At Oboui they excavated an undated iron forge yielding eight consistent radiocarbon dates of 2000 BCE. This would make Oboui the oldest iron-working site in the world, and more than a thousand years older than any other dated evidence of iron in Central Africa. Opinion among African archaeologists is sharply divided. Some specialists accept this interpretation, but archaeologist Bernard Clist has argued that Oboui is a highly disturbed site, with older charcoal having been brought up to the level of the forge by the digging of pits into older levels. Clist also raised questions about the unusually good state of preservation of metallic iron from the site. However, archaeologists such as Craddock, Eggert, and Holl have argued that such disturbance or disruption is highly unlikely given the nature of the site. Additionally, Holl, regarding the state of preservation, argues that this observation was based on published illustrations representing a small unrepresentative number of atypically well-preserved objects selected for publication. At Gbabiri, also in the Central African Republic, Eggert has found evidence of an iron reduction furnace and blacksmith workshop with earliest dates of 896–773 BCE and 907–796 BCE respectively.

In north-central Burkina Faso, remains of an iron smelting furnace near Douroula was also dated to the 8th century BCE, leading to the creation of the Ancient Ferrous Metallurgy Sites of Burkina Faso World Heritage Site. In the

All indigenous African iron smelting processes are variants of the

All indigenous African iron smelting processes are variants of the

Iron was not the only metal to be used in Africa;

Iron was not the only metal to be used in Africa;

MetalAfrica: a Scientific Network on African Metalworking

{{Authority control History of Africa Science and technology in Africa History of metallurgy + + + + Iron Age Africa Iron Age

ferrous metallurgy

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ...

on the African continent

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

. Whereas the development of iron metallurgy in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

and the Horn

Horn may refer to:

Common uses

* Horn (acoustic), a tapered sound guide

** Horn antenna

** Horn loudspeaker

** Vehicle horn

** Train horn

*Horn (anatomy), a pointed, bony projection on the head of various animals

* Horn (instrument), a family ...

closely mirrors that of the Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was home to many cradles of civilization, spanning Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran (or Persia), Anatolia and the Armenian highlands, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. As such, the fields of ancient Near East studies and Nea ...

and Mediterranean region, the three-age system

The three-age system is the periodization of human prehistory (with some overlap into the history, historical periods in a few regions) into three time-periods: the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age, although the concept may also re ...

is ill-suited to Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lie south of the Sahara. These include Central Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa, and West Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the list of sovereign states and ...

, where copper metallurgy generally does not precede iron working. Whether iron metallurgy in Sub-Saharan Africa originated as an independent innovation or a product of technological diffusion remains a point of contention between scholars. Following the beginning of iron metallurgy in Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

by 800 BC - 400 BC, and possibly earlier, agriculturalists of the Chifumbaze Complex would ultimately introduce the technology to Eastern and Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost region of Africa. No definition is agreed upon, but some groupings include the United Nations geoscheme for Africa, United Nations geoscheme, the intergovernmental Southern African Development Community, and ...

by the end of the first millennium AD.

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, radiocarbon

Carbon-14, C-14, C or radiocarbon, is a radioactive isotope of carbon with an atomic nucleus containing 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Its presence in organic matter is the basis of the radiocarbon dating method pioneered by Willard Libby and coll ...

and thermoluminescence dating

Thermoluminescence dating (TL) is the determination, by means of measuring the accumulated radiation dose, of the time elapsed since material containing crystalline minerals was either heated (lava, ceramics) or exposed to sunlight (sediment ...

of artifacts associated with iron metallurgy in Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

and the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to Central African Republic–Chad border, the north, Sudan to Central African Republic–Sudan border, the northeast, South Sudan to Central ...

have yielded dates as early as the third millennium BC

File:3rd millennium BC montage.jpg, 400x400px, From top left clockwise: Pyramid of Djoser; Khufu; Great Pyramid of Giza, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World; Cuneiform, a contract for the sale of a field and a house; Enheduana, a high ...

. Although a number of scholars have scrutinized these dates on methodological and theoretical grounds, others contend that they undermine the diffusionist model for the origins of iron metallurgy in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Iron metallurgy may have been independently developed in the Nok culture

The Nok culture is a population whose material remains are named after the Ham people, Ham village of Nok in Southern Kaduna, southern Kaduna State of Nigeria, where their terracotta sculptures were first discovered in 1928. The Nok people and ...

between the 9th century BCE and 550 BCE. The nearby Djenné-Djenno culture of the Niger Valley in Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

shows evidence of iron production from 250 BCE. The Bantu expansion

Bantu may refer to:

* Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

* Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

* Black Association for Natio ...

spread the technology to Eastern and Southern Africa between 500 BCE and 400 CE, as shown in the Urewe culture.

Origins and spread in Africa

Although the origins of iron working in Africa have been the subject of scholarly interest since the 1860s, it is still not known whether this technology diffused into sub-Saharan Africa from the Mediterranean region, or whether it was invented there independently of iron working elsewhere. Although some nineteenth-century European scholars favored an indigenous invention of iron working in sub-Saharan Africa, archaeologists writing between 1945 and 1965 mostly favored diffusion of iron smelting technology fromCarthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

across the Sahara to West Africa and/or from Meroe on the upper Nile to central Africa. This in turn has been questioned by more recent research which argues for an independent invention.

The invention of radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for Chronological dating, determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of carbon-14, radiocarbon, a radioactive Isotop ...

in the late 1950s enabled dating of metallurgical sites by the charcoal fuel used for smelting and forging. By the late 1960s some surprisingly early radiocarbon dates had been obtained for iron smelting sites in both Niger and central Africa (Rwanda, Burundi), reviving the view that iron-making was independently invented by Africans in sub-Saharan Africa as far back as 3600 BCE. These dates preceded the known antiquity of ironworking in Carthage or Meroe, weakening the diffusion hypothesis. In the 1990s, evidence was found of Phoenician iron smelting in the western Mediterranean (900–800 BCE),Descoeudres, E. Huysecom, V. Serneels and J.-L. Zimmermann (editors) (2001) ''The Origins of Iron Metallurgy: Proceedings of the First International Colloquium on The Archaeology of Africa and the Mediterranean Basin/Aux Origines de la Métallurgie du Fer: Actes de la Première Table Ronde Internationale d’Archéologie (L’Afrique et le Bassin Méditerranéen''). Special Issue of the journal ''Mediterranean Archaeology'' (volume 14) though specifically in North Africa it seems to date only to the 5th to 4th centuries BCE, or the 7th century BCE at the earliest, contemporary to or later than the oldest known iron metallurgy dates from sub-Saharan Africa. According to archaeometallurgist Manfred Eggert, "Carthage cannot be reliably considered the point of origin for sub-Saharan iron ore reduction." It is still not known when iron working was first practiced in Kush and Meroe in modern Sudan, but the earliest known iron metallurgy dates from Meroe and Egypt do not predate those from sub-Saharan Africa, and thus the Nile Valley is also considered unlikely to be the source of sub-Saharan iron metallurgy.

From the mid-1970s there were new claims for independent invention of iron smelting in central Niger and from 1994 to 1999 UNESCO funded an initiative "Les Routes du Fer en Afrique/The Iron Routes in Africa" to investigate the origins and spread of iron metallurgy in Africa. This funded both the conference on early iron in Africa and the Mediterranean and a volume, published by UNESCO, that generated some controversy because it included only authors sympathetic to the independent-invention view.

Two reviews of the evidence from the mid-2000s found technical flaws in the studies claiming independent invention, raising three major issues. The first was whether the material dated by radiocarbon was in secure archaeological association with iron-working residues. Many of the dates from Niger, for example, were on organic matter in potsherds that were lying on the ground surface together with iron objects. The second issue was the possible effect of "old carbon": wood or charcoal much older than the time at which iron was smelted. This is a particular problem in Niger, where the charred stumps of ancient trees are a potential source of charcoal, and have sometimes been misidentified as smelting furnaces. A third issue is the weaker precision of the radiocarbon method for dates between 800 and 400 BCE, attributable to irregular production of radiocarbon in the upper atmosphere. Unfortunately most radiocarbon dates for the initial spread of iron metallurgy in sub-Saharan Africa fall within this range.

Controversy flared again in 2007 with the publication of excavations by Étienne Zangato and colleagues in the Central African Republic. At Oboui they excavated an undated iron forge yielding eight consistent radiocarbon dates of 2000 BCE. This would make Oboui the oldest iron-working site in the world, and more than a thousand years older than any other dated evidence of iron in Central Africa. Opinion among African archaeologists is sharply divided. Some specialists accept this interpretation, but archaeologist Bernard Clist has argued that Oboui is a highly disturbed site, with older charcoal having been brought up to the level of the forge by the digging of pits into older levels. Clist also raised questions about the unusually good state of preservation of metallic iron from the site. However, archaeologists such as Craddock, Eggert, and Holl have argued that such disturbance or disruption is highly unlikely given the nature of the site. Additionally, Holl, regarding the state of preservation, argues that this observation was based on published illustrations representing a small unrepresentative number of atypically well-preserved objects selected for publication. At Gbabiri, also in the Central African Republic, Eggert has found evidence of an iron reduction furnace and blacksmith workshop with earliest dates of 896–773 BCE and 907–796 BCE respectively.

In north-central Burkina Faso, remains of an iron smelting furnace near Douroula was also dated to the 8th century BCE, leading to the creation of the Ancient Ferrous Metallurgy Sites of Burkina Faso World Heritage Site. In the

From the mid-1970s there were new claims for independent invention of iron smelting in central Niger and from 1994 to 1999 UNESCO funded an initiative "Les Routes du Fer en Afrique/The Iron Routes in Africa" to investigate the origins and spread of iron metallurgy in Africa. This funded both the conference on early iron in Africa and the Mediterranean and a volume, published by UNESCO, that generated some controversy because it included only authors sympathetic to the independent-invention view.

Two reviews of the evidence from the mid-2000s found technical flaws in the studies claiming independent invention, raising three major issues. The first was whether the material dated by radiocarbon was in secure archaeological association with iron-working residues. Many of the dates from Niger, for example, were on organic matter in potsherds that were lying on the ground surface together with iron objects. The second issue was the possible effect of "old carbon": wood or charcoal much older than the time at which iron was smelted. This is a particular problem in Niger, where the charred stumps of ancient trees are a potential source of charcoal, and have sometimes been misidentified as smelting furnaces. A third issue is the weaker precision of the radiocarbon method for dates between 800 and 400 BCE, attributable to irregular production of radiocarbon in the upper atmosphere. Unfortunately most radiocarbon dates for the initial spread of iron metallurgy in sub-Saharan Africa fall within this range.

Controversy flared again in 2007 with the publication of excavations by Étienne Zangato and colleagues in the Central African Republic. At Oboui they excavated an undated iron forge yielding eight consistent radiocarbon dates of 2000 BCE. This would make Oboui the oldest iron-working site in the world, and more than a thousand years older than any other dated evidence of iron in Central Africa. Opinion among African archaeologists is sharply divided. Some specialists accept this interpretation, but archaeologist Bernard Clist has argued that Oboui is a highly disturbed site, with older charcoal having been brought up to the level of the forge by the digging of pits into older levels. Clist also raised questions about the unusually good state of preservation of metallic iron from the site. However, archaeologists such as Craddock, Eggert, and Holl have argued that such disturbance or disruption is highly unlikely given the nature of the site. Additionally, Holl, regarding the state of preservation, argues that this observation was based on published illustrations representing a small unrepresentative number of atypically well-preserved objects selected for publication. At Gbabiri, also in the Central African Republic, Eggert has found evidence of an iron reduction furnace and blacksmith workshop with earliest dates of 896–773 BCE and 907–796 BCE respectively.

In north-central Burkina Faso, remains of an iron smelting furnace near Douroula was also dated to the 8th century BCE, leading to the creation of the Ancient Ferrous Metallurgy Sites of Burkina Faso World Heritage Site. In the Nsukka

Nsukka is a town and a Local Government Area in Enugu State, Nigeria. Nsukka shares a common border as a town with Edem, Opi (archaeological site), Ede-Oballa, and Obimo.

The postal code of the area is 410001 and 410002 respectively, re ...

region of southeast Nigeria (now Igboland

Igbo land ( Standard ) is a cultural and common linguistic region in southeastern Nigeria which is the indigenous homeland of the Igbo people. Geographically, it is divided into two sections, eastern (the larger of the two) and western. Its popu ...

), archaeological sites containing iron smelting furnaces and slag have been excavated dating to 750 BCE in Opi (Augustin Holl 2009) and 2,000 BCE in Lejja

Lejja is a community of 33 villages in Enugu State, southeastern Nigeria. Lejja is mainly inhabited by the Igbo people and is located on the edge of the Benue Plateau, which has rich laterite and basalt resources. Archaeological evidence of iron ...

(Pamela Eze-Uzomaka 2009). According to Augustin Holl (2018), there is evidence of ironworking dated to 2,153–2,044 BCE and 2,368–2,200 BCE from the site of Gbatoro, Cameroon.

Archaeometallurgical scientific knowledge and technological development originated in numerous centers of Africa; the centers of origin were located in West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

, Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

, and East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

; consequently, as these origin centers are located within inner Africa, these archaeometallurgical developments are thus native African technologies. Iron metallurgical development occurred 2631 BCE – 2458 BCE at Lejja, in Nigeria, 2136 BCE – 1921 BCE at Obui, in Central Africa Republic, 1895 BCE – 1370 BCE at Tchire Ouma 147, in Niger, and 1297 BCE – 1051 BCE at Dekpassanware, in Togo.

In 2014, archaeo-metallurgist Manfred Eggert argued that, though still inconclusive, the evidence overall suggests an independent invention of iron metallurgy in sub-Saharan Africa. In a 2018 study, archaeologist Augustin Holl also argues that an independent invention is most likely.

While the origins of iron smelting are difficult to date by radiocarbon, there are fewer problems with using it to track the spread of ironworking after 400 BCE. In the 1960s it was suggested that iron working was spread by speakers of Bantu languages

The Bantu languages (English: , Proto-Bantu language, Proto-Bantu: *bantʊ̀), or Ntu languages are a language family of about 600 languages of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern, East Africa, Eastern and Southeast Africa, South ...

, whose original homeland has been located by linguists in the Benue River valley of eastern Nigeria and Western Cameroon. Although some assert that no words for iron or ironworking can be traced to reconstructed proto-Bantu

Proto-Bantu is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Bantu languages, a subgroup of the Southern Bantoid languages. It is thought to have originally been spoken in West/Central Africa in the area of what is now Cameroon.Dimmendaal, Gerrit J. (2 ...

, place-names

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for a proper nam ...

in West Africa suggest otherwise, for example (Okuta) Ilorin, literally "site of iron-work". The linguist Christopher Ehret

Christopher Ehret (27 July 1941 – 25 March 2025), was an American scholar of African history and African historical linguistics who was particularly known for his efforts to correlate linguistic taxonomy and reconstruction with the archeologic ...

argues that the first words for iron-working in Bantu languages were borrowed from Central Sudanic languages in the vicinity of modern Uganda and Kenya, while Jan Vansina

Jan M. J. Vansina (14 September 1929 – 8 February 2017) was a Belgian historian and anthropologist regarded as an authority on the history of Central Africa, especially of what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi. ...

argues instead that they originated in non-Bantu languages in Nigeria, and that iron metallurgy spread southwards and eastwards to Bantu speakers, who had already dispersed into the Congo rainforest and the Great Lakes region. Archaeological evidence clearly indicates that starting in the first century BCE, iron and cereal agriculture (millet and sorghum) spread together southward from southern Tanzania and northern Zambia, all the way to the eastern Cape region of present South Africa by the third or fourth century CE. It seems highly probable that this occurred through migrations of Bantu-speaking peoples.

Techniques

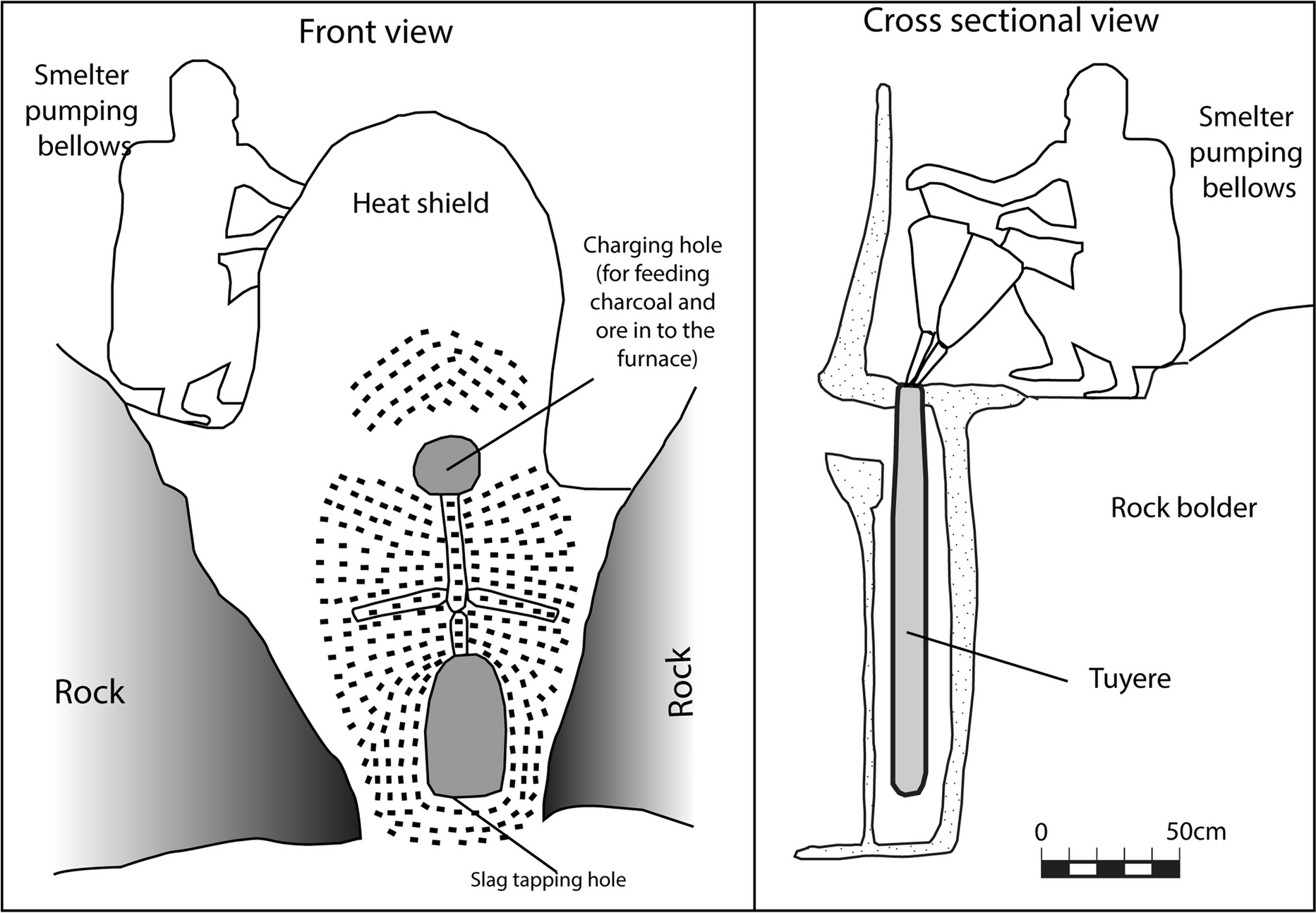

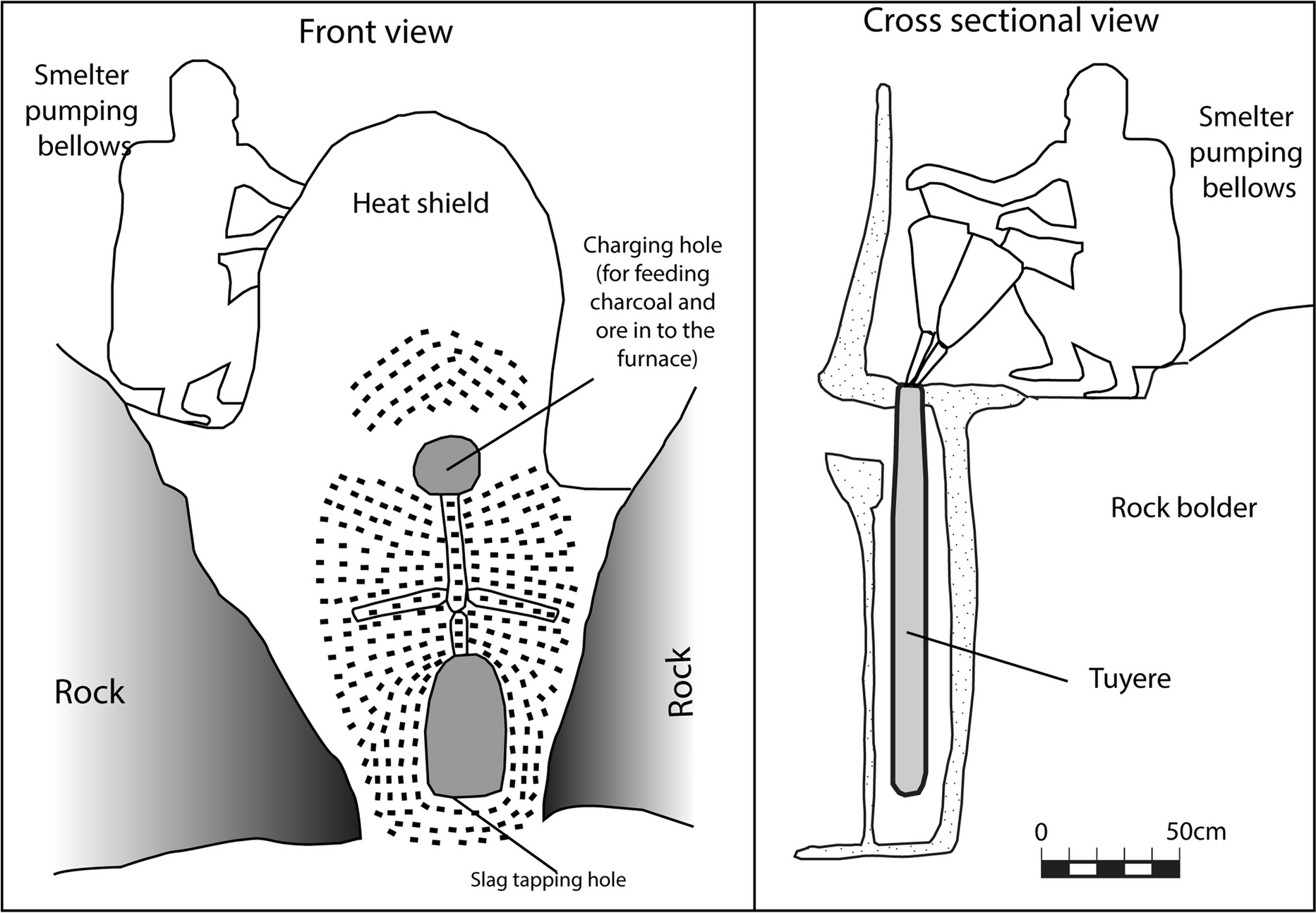

All indigenous African iron smelting processes are variants of the

All indigenous African iron smelting processes are variants of the bloomery

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its iron oxides, oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called ...

process. A much wider range of bloomery smelting processes has been recorded on the African continent than elsewhere in the Old World, probably because bloomeries remained in use into the 20th century in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, whereas in Europe and most parts of Asia they were replaced by the blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

In a ...

before most varieties of bloomeries could be recorded. W.W. Cline's compilation of eye-witness records of bloomery iron smelting over the past 250 years in Africa is invaluable, and has been supplemented by more recent ethnoarchaeological and archaeological studies. Furnaces used in the 19th and 20th centuries ranges from small bowl furnaces, dug down from the ground surface and powered by bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtig ...

, through bellows-powered shaft furnaces up to 1.5 m tall, to 6.5m natural-draft furnaces (i.e. furnaces designed to operate without bellows at all).

Over much of tropical Africa the ore used was laterite

Laterite is a soil type rich in iron and aluminium and is commonly considered to have formed in hot and wet tropical areas. Nearly all laterites are of rusty-red coloration, because of high iron oxide content. They develop by intensive and prolo ...

, which is widely available on the old continental cratons in West, Central and Southern Africa. Magnetite sand, concentrated in streams by flowing water, was often used in more mountainous areas, after beneficiation to raise the concentration of iron. Precolonial iron workers in present South Africa even smelted iron-titanium ores that modern blast furnaces are not designed to use. Bloomery furnaces were less productive than blast furnaces, but were far more versatile.

The fuel used was invariably charcoal, and the products were the bloom (a solid mass of iron) and slag

The general term slag may be a by-product or co-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and recycled metals depending on the type of material being produced. Slag is mainly a mixture of metal oxides and silicon dioxide. Broadly, it can be c ...

(a liquid waste product). African ironworkers regularly produced inhomogeneous steel blooms, especially in the large natural-draft furnaces. The blooms invariably contained some entrapped slag, and after removal from the furnace had to be reheated and hammered to expel as much of the slag as possible. Semi-finished bars of iron or steel were widely traded in some parts of West Africa, as for example at Sukur on the Nigeria-Cameroon border, which in the nineteenth century exported thousands of bars per year north to the Lake Chad Basin. Although many African ironworkers produced steel blooms, there is little evidence in sub-Saharan as yet for hardening of steel by quenching

In materials science, quenching is the rapid cooling of a workpiece in water, gas, oil, polymer, air, or other fluids to obtain certain material properties. A type of heat treating, quenching prevents undesired low-temperature processes, suc ...

and tempering or for the manufacture of composite tools combining a hard steel cutting edge with a soft but tough iron body. Relatively little metallography

Metallography is the study of the physical structure and components of metals, by using microscopy.

Ceramic and polymeric materials may also be prepared using metallographic techniques, hence the terms ceramography, plastography and, collecti ...

of ancient African iron tools has yet been done, so this conclusion may perhaps be modified by future work.

Unlike bloomery iron-workers in Europe, India or China, African metalworkers did not make use of water power to blow bellows in furnaces too large to be blown by hand-powered bellows. This is partly because sub-Saharan Africa has much less potential for water power than these other regions, but also because there were no engineering techniques developed for converting rotary motion to linear motion. African ironworkers did however invent a way to increase the size of their furnaces, and thus the amount of metal produced per charge, without using bellows. This was the natural-draft furnace, which is designed to reach the temperatures necessary to form and drain slag by using a chimney effect – hot air leaving the topic of the furnace draws in more air through openings at the base. (Natural-draft furnaces should not be confused with wind-powered furnaces, which were invariably small). The natural-draft furnace was the one African innovation in ferrous metallurgy

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ...

that spread widely. Natural draft furnaces were particularly characteristic of African savanna woodlands, and were used in two belts – across the Sahelian woodlands from Senegal in the west to Sudan in the east, and in the ''Brachystegia-Julbenardia'' (miombo) woodlands from southern Tanzania south to northern Zimbabwe. The oldest natural-draft furnaces yet found are in Burkina Faso and date to the seventh/eight centuries The large masses of slag (10,000 to 60,000 tons) noted in some locations in Togo, Burkina Faso and Mali reflect the great expansion of iron production in West Africa after 1000 CE that is associated with the spread of natural-draft furnace technology. But not all large scale iron production in Africa was associated with natural draft furnaces – those of Meroe (Sudan, first to fifth centuries CE) were produced by slag-tapping bellows-driven furnaces, and the large 18th-19th century iron industry of the Cameroon grasslands by non-tapping bellows-driven furnaces. All of the large-scale iron smelting recorded so far are in the Sahelian and Sudanic zones that stretch from Senegal in the west to Sudan in the east; there were no iron-smelting concentrations like these in central or southern Africa.

There is also evidence that carbon steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, cobalt ...

was made in Western Tanzania by the ancestors of the Haya people as early as 2,300-2,000 years ago by a complex process of "pre-heating" allowing temperatures inside a furnace to reach up to 1800°C.

These techniques are now extinct in all regions of sub-Saharan Africa, except, in the case of some of techniques, for some very remote regions of Ethiopia. In most regions of Africa they fell out of use before 1950. The main reason for this was the increasing availability of iron imported from Europe. Blacksmiths still work in rural areas of Africa to make and repair agricultural tools, but the iron that they use is imported, or recycled from old motor vehicles.

Uses

Iron was not the only metal to be used in Africa;

Iron was not the only metal to be used in Africa; copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

and brass

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, in proportions which can be varied to achieve different colours and mechanical, electrical, acoustic and chemical properties, but copper typically has the larger proportion, generally copper and zinc. I ...

were widely utilised too. However the steady spread of iron meant it must have had more favourable properties for many different uses. Its durability over copper meant that it was used to make many tools from farming pieces to weaponry. Iron was used for personal adornment in jewelry

Jewellery (or jewelry in American English) consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment such as brooches, ring (jewellery), rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the ...

, impressive pieces of artwork and even instruments. It was used for coins and currencies of varying forms. For example, kisi pennies; a traditional form of iron currency

Iron currency bars are objects used by Iron Age people to exchange goods.

Materials

The bars were expensive objects, as it would take 25 man-days to produce of a finished bar, usually shaped with a small socket at one end, and consume of char ...

used for trading in West Africa. They are twisted iron rods ranging from <30 cm to >2m in length. Suggestions for their uses vary from marital transactions, or simply that they were a convenient shape for transportation, melting down and reshaping into a desired object. There are many different forms of iron currency

Iron currency bars are objects used by Iron Age people to exchange goods.

Materials

The bars were expensive objects, as it would take 25 man-days to produce of a finished bar, usually shaped with a small socket at one end, and consume of char ...

, often regionally differing in shape and value. Iron did not replace other materials, such as stone and wooden tools, but the quantity of production and variety of uses met were significantly high by comparison.

Sociocultural significance

It is important to recognize that while iron production had great influence over Africa both culturally in trade and expansion (Martinelli, 1993, 1996, 2004), as well as socially in beliefs and rituals, there is great regional variation. Much of the evidence for cultural significance comes from the practises still carried out today by different African cultures. Ethnographical information has been very useful in reconstructing the events surrounding iron production in the past, however the reconstructions could have become distorted through time and influence by anthropologist's studies. The control of iron production was often by ironworkers themselves, or a "central power" in larger societies such as kingdoms or states (Barros 2000, p. 154). The demand for trade is believed to have resulted in some societies working only as smelters or smiths, specialising in just one of the many skills necessary to the production process. It is possible that this also led to tradesmen specialising in transporting and trading iron (Barros 2000, pg152). However, not every region benefited from industrialising iron production, others created environmental problems that arose due to the massive deforestation required to provide the charcoal for fuelling furnaces (for example the ecological crisis of the Mema Region (Holl 2000, pg48)). Iron smelters andsmith

Smith may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Metalsmith, or simply smith, a craftsman fashioning tools or works of art out of various metals

* Smith (given name)

* Smith (surname), a family name originating in England

** List of people ...

s received different social status depending on their culture. Some were lower in society due to the aspect of manual labour and associations with witchcraft, for example in the Maasai and Tuareg

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym, depending on variety: ''Imuhaɣ'', ''Imušaɣ'', ''Imašeɣăn'' or ''Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group, traditionally nomadic pastoralists, who principally inhabit th ...

(Childs et al. 2005 pg 288). In other cultures the skills are often passed down through family and would receive great social status (sometimes even considered as witchdoctors) within their community. Their powerful knowledge allowed them to produce materials on which the whole community relied. In some communities they were believed to have such strong supernatural powers that they were regarded as highly as the king or chief. For example, an excavation at the royal tomb of King Rugira (Great Lakes, Eastern Africa) found two iron anvil

An anvil is a metalworking tool consisting of a large block of metal (usually Forging, forged or Steel casting, cast steel), with a flattened top surface, upon which another object is struck (or "worked").

Anvils are massive because the hi ...

s placed at his head (Childs et al. 2005, p. 288 in Herbert 1993:ch.6). In some cultures mythical stories have been built around the premise of the iron smelter

Smelting is a process of applying heat and a chemical reducing agent to an ore to extract a desired base metal product. It is a form of extractive metallurgy that is used to obtain many metals such as iron, copper, silver, tin, lead and zin ...

emphasising their godlike significance.

Rituals

The smelting process was often carried out away from the rest of the community. Ironworkers engaged in rituals designed to encourage good production and to ward off bad spirits, including song and prayers, plus the giving of medicines and sacrifices. The latter were usually put in the furnace itself or buried under the base of the furnace. Examples of these date back as far as the early Iron Age inTanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

and Rwanda

Rwanda, officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of East Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator, Rwanda is bordered by ...

(Schmidt 1997 in Childs et al., 2005 p. 293). Men who possessed the knowledge and skills to work with iron, held a high social status and were often revered for their expertise. The ideology behind this was that, these 'Blacksmiths' possessed some spiritual and super human abilities which enabled them to extract the bloom from iron ore, eventually earning them a higher place of social status.

Some cultures associated sexual symbolism with iron production. Smelting was integrated with the fertility of their society, The production of the bloom was compared to human conception and birth. There were sexual taboos surrounding the process. The smelting process was carried out entirely by men and often away from the village. For women to touch any of the materials or be present could jeopardise the success of the production. The furnaces were also often adorned to resemble a woman, the mother of the bloom.

See also

* Copper metallurgy in Africa *Archaeology of Igbo-Ukwu

The archaeology of Igbo-Ukwu is the study of an archaeological site located in a town of the same name: Igbo-Ukwu, an Igbo town in Anambra State in southeastern Nigeria. As a result of these findings, three excavation areas at Igbo-Ukwu were op ...

* KM2 and KM3 sites

* Bantu expansion

Bantu may refer to:

* Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

* Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

* Black Association for Natio ...

* History of metallurgy in Africa

References

Bibliography

* Killick, D. 2004. Review Essay: "What Do We Know About African Iron Working?" ''Journal of African Archaeology''. Vol 2 (1) pp. 135–152 * Bocoum, H. (ed.), 2004, ''The origins of iron metallurgy in Africa – New lights on its antiquity'', H. Bocoum (ed.), UNESCO publishing * Schmidt, P.R., Mapunda, B.B., 1996. "Ideology and the Archaeological Record in Africa: Interpreting Symbolism in Iron Smelting Technology". ''Journal of Anthropological Archaeology''. Vol 16, pp. 73–102 * Rehren, T., Charlton, M., Shadrek, C., Humphris, J., Ige, A., Veldhuijen, H.A. "Decisions set in slag: the human factor in African iron smelting". La Niece, S., Hook, D., and Craddock, P., (eds). ''Metals and mines : studies in archaeometallurgy''. 2007, pp. 211–218. * Okafor, E.E., 1993. "New Evidence on Early Iron-Smelting from Southeastern Nigeria". Shaw, T., Sinclair, P., Bassey, A., Okpoko, A (eds). ''The Archaeology of Africa Food, Metals and Towns''. London, Routledge, pp. 432–448 * Kense, F.J., and Okora, J.A., 1993. "Changing Perspectives on Traditional Iron Production in West Africa". Shaw, T., Sinclair, P., Bassey, A., Okpoko, A (eds). ''The Archaeology of Africa Food, Metals and Towns''. London, Routledge, pp. 449– 458 * Muhammed, I.M., 1993. "Iron Technology in the Middle Sahel/Savanna: With Emphasis on Central Darfur". Shaw, T., Sinclair, P., Bassey, A., Okpoko, A (eds). ''The Archaeology of Africa Food, Metals and Towns''. London, Routledge, pp. 459–467 * Buleli, N'S., 1993. Iron-Making Techniques in the Kivu Region of Zaire: Some of the Differences Between the South Maniema Region and North Kivu. Shaw, T., Sinclair, P., Bassey, A., Okpoko, A (eds). ''The Archaeology of Africa Food, Metals and Towns''. London, Routledge, pp. 468–477 * Radimilahy, C., 1993 "Ancient Iron-Working in Madagascar". Shaw, T., Sinclair, P., Bassey, A., Okpoko, A (eds). ''The Archaeology of Africa Food, Metals and Towns''. London, Routledge, pp. 478–473 * Kiriama, H.O., 1993. "The Iron Using Communities in Kenya". Shaw, T., Sinclair, P., Bassey, A., Okpoko, A (eds). ''The Archaeology of Africa Food, Metals and Towns''. London, Routledge, pp. 484–498 * Martinelli, B., 1993, "Fonderies ouest-africaines. Classement comparatif et tendances", in ''Atouts et outils de l'ethnologie des techniques – Sens et tendance en technologie comparée, Revue Techniques et culture'', no 21 : 195–221. * Martinelli, B., 2004, "On the Threshold of Intensive Metallurgy – The choice of Slow Combustion in the Niger River Bend (Burkina Faso and Mali)" ''in The origins of iron metallurgy in Africa – New lights on its antiquity'', H. Bocoum (ed.), UNESCO publishing : pp. 216–247 * Collet, D.P., 1993. "Metaphors and Representations Associated with Precolonial Iron-Smelting in Eastern and Southern Africa". Shaw, T., Sinclair, P., Bassey, A., Okpoko, A (eds). ''The Archaeology of Africa Food, Metals and Towns''. London, Routledge, pp. 499–511Further reading

*External links

MetalAfrica: a Scientific Network on African Metalworking

{{Authority control History of Africa Science and technology in Africa History of metallurgy + + + + Iron Age Africa Iron Age