Adrian Woodruffe-Peacock on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

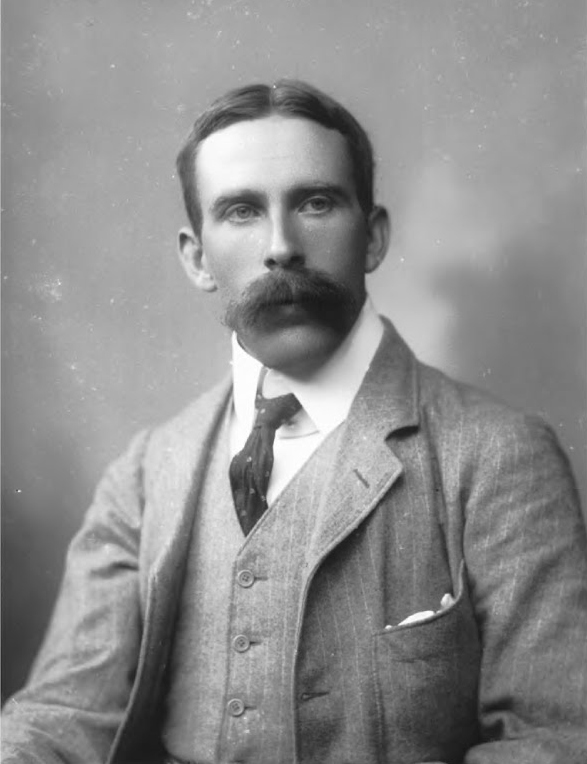

Edward Adrian Woodruffe-Peacock (23 July 1858 – 3 February 1922) was an English clergyman and

Woodruffe-Peacock, always known by his middle name of Adrian, was born at Bottesford Manor, north Lincolnshire, on 23 July 1858, the son of Edward Peacock (1831–1915), farmer, antiquarian, historian, and author, and his wife, Lucy Ann Wetherell (1823–1887). He had 6 siblings, including the folklorist Mabel Peacock. He was schooled at

Woodruffe-Peacock, always known by his middle name of Adrian, was born at Bottesford Manor, north Lincolnshire, on 23 July 1858, the son of Edward Peacock (1831–1915), farmer, antiquarian, historian, and author, and his wife, Lucy Ann Wetherell (1823–1887). He had 6 siblings, including the folklorist Mabel Peacock. He was schooled at

In 1891 he accepted the living at

In 1891 he accepted the living at  Woodruffe-Peacock compiled a ''Critical Catalogue of Lincolnshire Plants'' (1894–1900), superseded by his ''Check-List of Lincolnshire Plants'' (1909), allegedly based on an analysis of half a million observations. In compiling the checklist he worked with botanists including: C.S. Stow, W. W.Mason, A. Bennet, J. Britten, W.H. Beeby, F.A. Lees, and Canon Fowler.

He took a leading role in the foundation of the Lincolnshire Naturalists' Union in 1893, serving as organizing secretary in 1895 and president in 1905. He was the prime mover in establishing a museum for Lincolnshire, his extensive herbarium forming an integral part of its original collections and the foundation of the city and county museum's herbarium. He was elected a fellow of both the

Woodruffe-Peacock compiled a ''Critical Catalogue of Lincolnshire Plants'' (1894–1900), superseded by his ''Check-List of Lincolnshire Plants'' (1909), allegedly based on an analysis of half a million observations. In compiling the checklist he worked with botanists including: C.S. Stow, W. W.Mason, A. Bennet, J. Britten, W.H. Beeby, F.A. Lees, and Canon Fowler.

He took a leading role in the foundation of the Lincolnshire Naturalists' Union in 1893, serving as organizing secretary in 1895 and president in 1905. He was the prime mover in establishing a museum for Lincolnshire, his extensive herbarium forming an integral part of its original collections and the foundation of the city and county museum's herbarium. He was elected a fellow of both the

ecologist

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere levels. Ecology overlaps with the closely re ...

. He was an early exponent of the ecological approach to natural history recording.

Early life

Woodruffe-Peacock, always known by his middle name of Adrian, was born at Bottesford Manor, north Lincolnshire, on 23 July 1858, the son of Edward Peacock (1831–1915), farmer, antiquarian, historian, and author, and his wife, Lucy Ann Wetherell (1823–1887). He had 6 siblings, including the folklorist Mabel Peacock. He was schooled at

Woodruffe-Peacock, always known by his middle name of Adrian, was born at Bottesford Manor, north Lincolnshire, on 23 July 1858, the son of Edward Peacock (1831–1915), farmer, antiquarian, historian, and author, and his wife, Lucy Ann Wetherell (1823–1887). He had 6 siblings, including the folklorist Mabel Peacock. He was schooled at Edinburgh Academy

The Edinburgh Academy is a Private schools in the United Kingdom, private day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, which was opened in 1824. The original building, on Henderson Row in Stockbridge, Edinburgh, Stockbridge, is now part of the Senior Scho ...

(1870–73) and St Peter's School, York

St Peter's School is a mixed-sex education, co-educational Private schools in the United Kingdom, private boarding and day school (also referred to as a Public school (United Kingdom), public school), in the English City of York, with extensive ...

(1873). He then received private tuition in Lincolnshire until April 1877, when he was admitted to St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College, formally the College of St John the Evangelist in the University of Cambridge, is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge, founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch L ...

, to study mathematics, classics, science, and natural history. Shortage of money, poor health, and the decision to become an Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

clergyman cut short his stay there.

In 1879 he transferred to Bishop Hatfield's Hall at Durham University

Durham University (legally the University of Durham) is a collegiate university, collegiate public university, public research university in Durham, England, founded by an Act of Parliament (UK), Act of Parliament in 1832 and incorporated by r ...

. At Durham, he indulged in extensive botanising, boating

Boating is the leisurely activity of travelling by boat, or the recreational use of a boat whether powerboats, sailboats, or man-powered vessels (such as rowing and paddle boats), focused on the travel itself, as well as sports activities, suc ...

, and tennis; his social life being so time-consuming that there were complaints he regarded the university as a private club

A club is an association of people united by a common interest or goal. A service club, for example, exists for voluntary or charitable activities. There are clubs devoted to hobbies and sports, social activities clubs, political and religious ...

. He sat for the degree examination at Easter 1881, but "scratched", thinking that he had failed his Latin paper and choosing to make arrangements to leave before receiving the results. However, this did not affect his career as he had already obtained his licentiate of theology in December 1880, and was subsequently ordained deacon in December 1881, and then priest in December 1883. Following university he held curacies at: Long Benton, Northumberland (1881–84); Barkingside, Essex (1884–85); Long Benton (1885–86); and finally at Harrington, Northamptonshire

Harrington is a village and civil parish in Northamptonshire, England, administered by North Northamptonshire council. At the time of the 2001 census, the parish's population was 154 people, including Thorpe Underwood but reducing to 146 at t ...

(1886–90).

Ecology

In 1891 he accepted the living at

In 1891 he accepted the living at Cadney

Cadney is a village and civil parish in the North Lincolnshire district, in the county of Lincolnshire, England. The population of the parish at the 2011 census was 459. It is situated south from the town of Brigg.

Cadney's Grade I listed Ang ...

, 10 miles from his birthplace, where he stayed until 1920 and developed a reputation as a naturalist. This was a poor, sparsely populated parish; since Woodruffe-Peacock had to visit his widely scattered parishioners on foot, he became by inclination and necessity a tremendous walker, which afforded him the opportunity to make regular observations and to record the natural changes occurring over a limited area. His profile in the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

'' notes that his routes contained some of the best observed and documented habitats in the country.

Woodruffe-Peacock compiled a ''Critical Catalogue of Lincolnshire Plants'' (1894–1900), superseded by his ''Check-List of Lincolnshire Plants'' (1909), allegedly based on an analysis of half a million observations. In compiling the checklist he worked with botanists including: C.S. Stow, W. W.Mason, A. Bennet, J. Britten, W.H. Beeby, F.A. Lees, and Canon Fowler.

He took a leading role in the foundation of the Lincolnshire Naturalists' Union in 1893, serving as organizing secretary in 1895 and president in 1905. He was the prime mover in establishing a museum for Lincolnshire, his extensive herbarium forming an integral part of its original collections and the foundation of the city and county museum's herbarium. He was elected a fellow of both the

Woodruffe-Peacock compiled a ''Critical Catalogue of Lincolnshire Plants'' (1894–1900), superseded by his ''Check-List of Lincolnshire Plants'' (1909), allegedly based on an analysis of half a million observations. In compiling the checklist he worked with botanists including: C.S. Stow, W. W.Mason, A. Bennet, J. Britten, W.H. Beeby, F.A. Lees, and Canon Fowler.

He took a leading role in the foundation of the Lincolnshire Naturalists' Union in 1893, serving as organizing secretary in 1895 and president in 1905. He was the prime mover in establishing a museum for Lincolnshire, his extensive herbarium forming an integral part of its original collections and the foundation of the city and county museum's herbarium. He was elected a fellow of both the Linnean Society

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature collec ...

and the Geological Society

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe, with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

in 1895. Among his achievements was the pioneering of the small-scale ecological survey. He also appreciated the mechanisms of dispersal, a neglected aspect of British ecology, which he approached through the careful study of microhabitats

In ecology, habitat refers to the array of resources, biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species' habitat can be seen as the physical manifestation of its ...

. As the result of "half a dozen visits" to a Lincolnshire beck during a dry summer when the water was low, he noted over 58 species growing, coming from the seeds he had dispersed by the stream. He was also a pioneer in plotting the distribution of plants. As early as 1894 he had 20,000 "place notes" on the distribution of plant species tabulated in his "Locality Register".

He published an article, "A fox-covert study" in the ''Journal of Ecology

The ''Journal of Ecology'' is a bimonthly peer-reviewed scientific journal covering all aspects of the ecology of plants. It was established in 1913 and is published by Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the British Ecological Society.

The journal pub ...

'', recently founded by botanist Arthur Tansley

Sir Arthur George Tansley FLS, FRS (15 August 1871 – 25 November 1955) was an English botanist and a pioneer in the science of ecology.

Educated at Highgate School, University College London and Trinity College, Cambridge, Tansley taught ...

. The two eventually met on a field trip to Mildenhall in Suffolk

Suffolk ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Norfolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Essex to the south, and Cambridgeshire to the west. Ipswich is the largest settlement and the county ...

and, surprisingly, since Tansley was an avowed atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

, became close friends. By this point Woodruffe-Peacock had been working on a detailed study, ''Rock-soil flora of Lincolnshire'', for many years, and Tansley, impressed, offered to contribute £300 towards its publication. Owing to poor health, Woodruffe-Peacock was never able to make the necessary revisions and only a small section was ever published, the rest of the manuscript passing into the archives of Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University Library is the main research library of the University of Cambridge. It is the largest of over 100 libraries Libraries of the University of Cambridge, within the university. The library is a major scholarly resource for me ...

. According to Brian J. Ford, these extensive notes show him to be ahead of his time in his approach to natural history.

Personal

Woodruffe-Peacock was tall and broad in proportion, but his health did not match up to his stature: most of his life he suffered from chronic hay fever andrheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorders are conditions causing chronic, often intermittent pain affecting the joints or connective tissue. Rheumatism does not designate any specific disorder, but covers at least 200 different conditions, including a ...

. In 1920, by now Rector of Grayingham, he suffered an emotional setback when his sister Mabel died. A combination of this, the pressures of his new appointment, and the disappointment of his magnum opus

A masterpiece, , or ; ; ) is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, skill, profundity, or workmanship.

Historically, ...

requiring so many revisions, saw his health break down. He died on 3 February 1922 and was buried in an unmarked grave

An unmarked grave is one that lacks a marker, headstone, or nameplate indicating that a body is buried there. It may also include burials that previously had identification but which are no longer identifiable due to weather damage, neglect, dist ...

beside his sister.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Woodruffe-Peacock, Adrian 1858 births 1922 deaths 19th-century English Anglican priests 20th-century English Anglican priests English botanical writers British ecologists Alumni of Hatfield College, Durham People educated at Edinburgh Academy Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge Durham University Boat Club rowers People educated at St Peter's School, York Fellows of the Linnean Society of London Fellows of the Geological Society of London People from the Borough of North Lincolnshire British male rowers Members of the Lincolnshire Naturalists' Union