Admiral Robert Blake on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Blake (27 September 1598 – 7 August 1657) was an English naval officer who served as general at sea and the

In April, 1640, Blake was elected as the Member of

In April, 1640, Blake was elected as the Member of

In February 1656 commercial rivalry with Spain was soon turned to war. In the Anglo-Spanish War Blake blockaded

In February 1656 commercial rivalry with Spain was soon turned to war. In the Anglo-Spanish War Blake blockaded

On 13 March 1655, Blake, still in active service while aboard the ''Naseby'', made out his last will and testament. The first item, consisting of a paragraph, began with, "I bequeath my soul unto the hands of my most merciful Redeemer, the Lord Jesus Christ..." He left the towns of Bridgwater and Taunton £100 each to be dispersed among the poor. He left his brother Humphrey his manor house, while leaving his other brothers considerable sums of money. Among other items bequeathed to other family members and friends, he left the gold chain that was awarded him by the Parliament to his nephew Robert, son of his deceased brother.

After again cruising off Cadiz for a while, Blake, aboard his flagship ''George'' turned for home, but on 7 August 1657 at ten o'clock in the morning he died of old wounds within sight of

On 13 March 1655, Blake, still in active service while aboard the ''Naseby'', made out his last will and testament. The first item, consisting of a paragraph, began with, "I bequeath my soul unto the hands of my most merciful Redeemer, the Lord Jesus Christ..." He left the towns of Bridgwater and Taunton £100 each to be dispersed among the poor. He left his brother Humphrey his manor house, while leaving his other brothers considerable sums of money. Among other items bequeathed to other family members and friends, he left the gold chain that was awarded him by the Parliament to his nephew Robert, son of his deceased brother.

After again cruising off Cadiz for a while, Blake, aboard his flagship ''George'' turned for home, but on 7 August 1657 at ten o'clock in the morning he died of old wounds within sight of  In 1926 the house in Bridgwater, where it is believed that Blake was born, was purchased and turned into the Blake Museum, where a room is devoted to him and his exploits.

Blake is one of four maritime figures depicted with a statue on the facade of Deptford Town Hall, in the London Borough of Lewisham. Blake and his

In 1926 the house in Bridgwater, where it is believed that Blake was born, was purchased and turned into the Blake Museum, where a room is devoted to him and his exploits.

Blake is one of four maritime figures depicted with a statue on the facade of Deptford Town Hall, in the London Borough of Lewisham. Blake and his

1899, Lawrence and Bullen, Ltd. publication

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Blake Museum, Bridgwater

*

Admiral Blake

– Article in Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, 29 May 1852

Robert Blake, admiral and general at sea

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports is the name of a ceremonial post in the United Kingdom. The post dates from at least the 12th century, when the title was Keeper of the Coast, but it may be older. The Lord Warden was originally in charge of the ...

from 1656 to 1657. Blake served under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

during the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

and Anglo-Spanish War, and as the commanding Admiral of the State's Navy during the First Anglo-Dutch War

The First Anglo-Dutch War, or First Dutch War, was a naval conflict between the Commonwealth of England and the Dutch Republic. Largely caused by disputes over trade, it began with English attacks on Dutch merchant shipping, but expanded to vast ...

. Blake is recognized as the "chief founder of England's naval supremacy", a dominance subsequently inherited by the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

well into the early 20th century.Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

Despite this, due to deliberate attempts to expunge the Parliamentarians from historical records following the Stuart Restoration

The Stuart Restoration was the reinstatement in May 1660 of the Stuart monarchy in Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland. It replaced the Commonwealth of England, established in January 164 ...

, Blake's achievements tend to remain relatively unrecognized. Blake's successes, however, are considered to have "never been excelled, not even by Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

" according to one biographer, Yexley, 1911, p. 22 while Blake is often compared with Nelson by others.

Early life

Robert Blake was the first son of thirteen children born to Humphrey Blake and Sarah Williams. He was baptized at the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin in Somerset on 27 September 1598. Baumber, 2004, v. 6, p. 107 He attended Bridgwater Grammar School for Boys, then went toWadham College

Wadham College ( ) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is located in the centre of Oxford, at the intersection of Broad Street and Parks Road. Wadham College was founded in 1610 by Dorothy Wadham, a ...

, Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

. He had hoped to follow an academic career, but failed to secure a fellowship to Merton College

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the 1260s when Walter de Merton, chancellor ...

, probably in consideration of his political and religious views, but also because the warden of Merton, Sir Henry Savile, had 'an eccentric distaste for men of low stature'. Blake, at tall, thus failed to meet Savile's 'standard of manly beauty'.

When Blake's father died in 1625 he inherited the family estate of Knoll Hill. Here, taking on the responsibilities of the eldest son, he took committed much of his time in the duty of educating his many brothers and sisters, and preparing them for adulthood. Blake biographer and historian David Hannay (1853–1934) maintains that was a likely reason why Blake never married, while pointing out also that other biographers offer differing reasons. English historian Edward Hyde, who lived in Blake's day writes of Blake, "...he was well enough versed in books for a man who intended not to be of any profession, having sufficient of his own to maintain him in the plenty he affected, and having then no appearance of ambition to be a greater man than he was."

The Blake family had a seat for several generations at (and were Lords of the Manor of) Tuxwell, in the parish of Bishops Lydeard, near Bridgwater

Bridgwater is a historic market town and civil parish in Somerset, England. The town had a population of 41,276 at the 2021 census. Bridgwater is at the edge of the Somerset Levels, in level and well-wooded country. The town lies along both sid ...

, Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

. The earliest member of the family located in records was Humphrey Blake, who lived in the reign of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

. Robert Blake's grandfather, also named Robert, was the first of the family to strike out on his own from country life as a merchant, hoping to become rich from Spanish trade. He served as chief magistrate and member of Parliament for Bridgwater several times, in recognition of the esteem in which the townspeople held him. His son, Humphrey, succeeded him in business, and in addition to his father's estates at Puriton (of which he held the lordship), Catcot, Bawdrip and Woolavington, came into the estate at Plainsfield held by the family of his wife, Sarah Williams, since the reign of Henry VII.

After his departure from university in 1625, it is believed that Blake was engaged in trade, and a Dutch writer subsequently claimed that he had lived for 'five or six years' in Schiedam

Schiedam () is a large town and municipality in the west of the Netherlands. It is located in the Rotterdam–The Hague metropolitan area, west of the city Rotterdam, east of the town Vlaardingen and south of the city Delft. In the south, Schi ...

. Having returned to Bridgwater, probably because of the death of his mother in 1638, he decided to stand for election to Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

.

Political background

Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

for Bridgwater

Bridgwater is a historic market town and civil parish in Somerset, England. The town had a population of 41,276 at the 2021 census. Bridgwater is at the edge of the Somerset Levels, in level and well-wooded country. The town lies along both sid ...

in the Short Parliament

The Short Parliament was a Parliament of England that was summoned by King Charles I of England on 20 February 1640 and sat from 13 April to 5 May 1640. It was so called because of its short session of only three weeks.

After 11 years of per ...

, as one of two Burgesses for Bridgwater. When the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

broke out during the period of the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an Parliament of England, English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660, making it the longest-lasting Parliament in English and British history. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened f ...

, and having failed to be re-elected in November, Blake began his military career on the side of the parliamentarians despite having no substantial experience of military or naval matters.

Blake returned to Parliament as member for Taunton in 1645, when the Royalist Colonel Windham was expelled. Mirza, 1911, v. iv, p. 35 He would later return to recover from an injury sustained in the Battle of Portland. During that time he represented Bridgwater in the Barebone's Parliament of 1653 and First Protectorate Parliament

The First Protectorate Parliament was summoned by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell under the terms of the Instrument of Government. It sat for one term from 3 September 1654 until 22 January 1655 with William Lenthall as the Speaker of the H ...

of 1654 and Taunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England. It is a market town and has a Minster (church), minster church. Its population in 2011 was 64,621. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century priory, monastic foundation, owned by the ...

in the Second Protectorate Parliament

The Second Protectorate Parliament in England sat for two sessions from 17 September 1656 until 4 February 1658, with Thomas Widdrington as the Speaker of the House of Commons (United Kingdom), Speaker of the House of Commons. In its first sess ...

of 1656 before returning to sea.

Naval service

Blake is often referred to as the 'Father of the Royal Navy'. As well as being largely responsible for building the largest navy the country had ever known, from a few tens of ships to well over a hundred, he was also the first to keep a fleet at sea over the winter. Blake also produced the navy's first ever set of rules and regulations, ''The Laws of War and Ordinances of the Sea'', the first version of which, containing 20 provisions, was passed by the House of Commons on 5 March 1649, listing 39 offences and their punishments—mostly death. The ''Instructions of the Admirals and Generals of the Fleet for Councils of War'', issued in 1653 by Blake, George Monck, John Disbrowe andWilliam Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer, religious thinker, and influential Quakers, Quaker who founded the Province of Pennsylvania during the British colonization of the Americas, British colonial era. An advocate of democracy and religi ...

, also instituted the first naval courts-martial in the English navy.

Blake developed new techniques to conduct blockades and landings; his ''Sailing Instructions'' and ''Fighting Instructions'', which were major overhauls of naval tactics written while recovering from injury in 1653, were the foundation of English naval tactics in the Age of Sail. Blake's ''Fighting Instructions'', issued by the generals at sea on 29 March 1653, are the first-known instructions to be written in any language to adopt the use of the single line ahead battle formation. Blake was also the first to successfully attack despite fire from shore forts.

English Civil War

upright=0.8, Before Blake embarked on a naval career he joined theNew Model Army

The New Model Army or New Modelled Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 t ...

as a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

in Alexander Popham

Alexander Popham (1605 – 1669) of Littlecote, Wiltshire, was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1640 and 1669. He was patron of the philosopher John Locke.

Early life

Popham was born at Littlec ...

's regiment, Blake distinguished himself at the Siege of Bristol (July 1643) and was promoted to lieutenant colonel. After his leading role in holding Lyme Regis in the Siege of Lyme Regis (April 1644) he was promoted to colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

. He went on to hold the Parliamentary enclave of Taunton during the Siege of Taunton in 1645. Taunton was of great strategic importance as it was situated where all the main roads converged, commanding all lines of communication, which at the time Blake alone understood. After he took it by surprise, the siege earned him national recognition; it was where he famously declared that he would eat three of his four pairs of boots before he would surrender. He subsequently succeeded in winning the Siege of Dunster (November 1645).

In March 1649 the newly established Commonwealth government appointed Popham, Blake and Deane as Generals at Sea, in that respective order of command, even though Blake had little experience at sea up until that time. With Deane committed in Scotland, Blake's first naval commission was in 1649, as second in command of the Dutch Navy against a domestic enemy with the objective of crushing the weary remnants of the Royalist party. King Charles I's followers were completely conquered and expelled from the mainland in England, but they still continued to fight on the sea and were taking many prizes, causing outcries from many of the merchants. Parliament was thus compelled to establish a naval administration, which appointed Blake, Popham and Deane as commanders of a fleet they were putting together and outfitting. Some three weeks before the execution of Charles I

Charles_I_of_England, Charles I, King of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, was executed on Tuesday, 30 January 1649 outside the Banqueting House on Whitehall, London. The execution was ...

, on 11 January 1649, Prince Rupert of the Rhine

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 ( O.S.) 7 December 1619 (N.S.)– 29 November 1682 (O.S.) December 1682 (N.S) was an English-German army officer, admiral, scientist, and colonial governor. He first rose to ...

led eight undermanned ships to Kinsale where the King's flag was still flying, in Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, in an attempt to prevent the Parliamentarians taking Ireland from the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

s. Blake blockaded Rupert's fleet in Kinsale from 22 May, allowing Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

, who placed great confidence in Blake, to land at Dublin on 15 August. Blake was driven off by a storm in October and Rupert escaped via Spain to Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

. When it was learned that Rupert had fled to Lisbon, all cautionary protocols were suspended for the navy. Blake was recalled to Plymouth to supervise the fitting out of a fleet that was expanded to thirteen ships. With his refurbished and well supplied fleet, Blake put to sea in February 1650 and dropped anchor off Lisbon in an attempt to persuade the Portuguese king to expel Rupert. After two months the king decided to back Rupert. Blake was joined by another eight warships commanded by Edward Popham, who brought authority to go to war with Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

. Blake now bore the risk and responsibility of a prolonged blockade, where now neither food nor water were accessible from the shore, making it necessary to periodically dispatch ships to Vigo

Vigo (, ; ) is a city and Municipalities in Spain, municipality in the province of province of Pontevedra, Pontevedra, within the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Spain. Located in the northwest ...

or Cádiz

Cádiz ( , , ) is a city in Spain and the capital of the Province of Cádiz in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. It is located in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula off the Atlantic Ocean separated fr ...

for supplies, to which Richard Bidley, 1899 was given the charge.

Rupert twice failed to break the blockade, which was finally raised after Blake sailed for Cádiz

Cádiz ( , , ) is a city in Spain and the capital of the Province of Cádiz in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. It is located in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula off the Atlantic Ocean separated fr ...

with seven ships he had captured after a three-hour engagement with 23 ships of the Portuguese fleet (during which the Portuguese vice-admiral was also sunk.) Blake re-engaged with Rupert, now with six ships, on 3 November near Málaga, capturing one ship. Two days later Rupert's other ships in the area were driven ashore attempting to escape from Cartagena, securing Parliamentarian supremacy at sea, and the recognition of the Parliamentary government by many European states. Parliament voted Blake 1,000 pounds by way of thanks in February 1651. In June of the same year Blake captured the Isles of Scilly

The Isles of Scilly ( ; ) are a small archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, Isles of Scilly, St Agnes, is over farther south than the most southerly point of the Great Britain, British mainla ...

, the last outpost of the Royalist navy, for which he again received Parliament's thanks. Soon afterwards he was made a member of the Council of State

A council of state is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head ...

.

In 1651 Blake received orders to remove the Royalist Sir John Granville from the Isles of Scilly

The Isles of Scilly ( ; ) are a small archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, Isles of Scilly, St Agnes, is over farther south than the most southerly point of the Great Britain, British mainla ...

, where he had been appointed Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

by Charles II after a local rebellion. Granville had around 1,000 men under his command. The majority of Royalists forces were holding the main island of St Mary's, also defended by the guns of Star Castle

''Star Castle'' is a vector graphics multidirectional shooter released in arcades by Cinematronics in 1980. The game involves obliterating a series of defenses orbiting a stationary turret in the center of the screen. The display is black and wh ...

and several frigates anchored, including the most powerful of the Royalist warships, making a direct assault very dangerous. Blake subsequently decided to secure Tresco Tresco may refer to:

* Tresco, Elizabeth Bay, a historic residence in New South Wales, Australia

* Tresco, Isles of Scilly, an island off Cornwall, England, United Kingdom

* Tresco, Victoria, a town in Victoria, Australia

* a nickname referring t ...

and Bryher first, which would give the Commonwealth force a safe anchorage at New Grimsby harbour. After a failed attempt due to unfavourable winds, and other delays Blake finally prevailed and demanded Granville's surrender and ultimately secured the isles, also capturing many commanders and supplies

First Anglo-Dutch War

Blake's next adventures were during theFirst Anglo-Dutch War

The First Anglo-Dutch War, or First Dutch War, was a naval conflict between the Commonwealth of England and the Dutch Republic. Largely caused by disputes over trade, it began with English attacks on Dutch merchant shipping, but expanded to vast ...

(1652–1654). The war started prematurely with a skirmish between the Dutch fleet of Maarten Tromp

Maarten Harpertszoon Tromp or Maarten van Tromp (23 April 1598 – 31 July 1653) was an army general and admiral in the Dutch navy during much of the Eighty Years' War and throughout the First Anglo-Dutch War. Son of a ship's captain, Tromp spe ...

and Blake on 29 May 1652, at the Battle of Dover.

On 19 May 1652, Tromp was patrolling in the English Channel with a fleet of forty ships between Nieuport

Nieuport, later Nieuport-Delage, was a French aeroplane company that primarily built racing aircraft before World War I and fighter aircraft during World War I and between the wars.

History

Beginnings

Originally formed as Nieuport-Duplex in ...

and the mouth of the Meuse River

The Meuse or Maas is a major European river, rising in France and flowing through Belgium and the Netherlands before draining into the North Sea from the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. It has a total length of .

History

From 1301, the upp ...

, to provide protection Dutch merchant ships, while monitoring the activity of the English fleet who had been seizing Dutch merchant ships. Blake was lying in Dover

Dover ( ) is a town and major ferry port in Kent, southeast England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies southeast of Canterbury and east of Maidstone. ...

Roads with fifteen ships, with eight others in reserve of the coast of Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

in The Downs. When Tromp failed to lower his flag in salute, Blake, aboard his flagship the ''James'', believing Tromp had just received orders from a Dutch dispatch ketch to commence battle, fired two warning shots, without ball. Subsequently the Battle of Dover began when Tromp refused to strike his flag, but instead hoisted a red battle flag in defiance. This caused Blake to fire a third gun, damaging Tromp's ship and wounding some crew members. Tromp in return fired a warning broadside from his flagship ''Brederode''. Blake in turn fired a broadside and a five-hour battle ensued. The fighting continued until nightfall, where both sides withdrew, the battle having no distinct victor. Low, 1872, p. 36

The proper war started in June with an English campaign against the Dutch East Indies, Baltic and fishing trades by Blake, in command of around 60 ships. On 5 October 1652 Dutch Vice-Admiral Witte Corneliszoon de With, underestimating the strength of the English, attempted to attack Blake, but due to the weather it was Blake who attacked on 8 October 1652 in the Battle of the Kentish Knock, sending de With back to the Netherlands in defeat. The English government seemed to think that the war was over and sent ships away to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

. Blake had only 42 warships when he was attacked and decisively defeated by 88 Dutch ships under Tromp on 9 December 1652 in the Battle of Dungeness

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

, losing control of the English Channel to the Dutch. Meanwhile, the ships sent away had also been defeated in the Battle of Leghorn

The naval Battle of Leghorn took place on 4 March 1653 (14 March Gregorian calendar),

during the First Anglo-Dutch War, near Leghorn (Livorno), Italy. It was a victory of a Dutch Republic, Dutch squadron under Commodore (rank), Commodore Johan ...

. Following the navy's poor performance at Dungeness, Blake demanded that the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty

The Board of Admiralty (1628–1964) was established in 1628 when Charles I put the office of Lord High Admiral into commission. As that position was not always occupied, the purpose was to enable management of the day-to-day operational requi ...

enact major reforms. They complied by, among other things, enacting Articles of War

The Articles of War are a set of regulations drawn up to govern the conduct of a country's military and naval forces. The first known usage of the phrase is in Robert Monro's 1637 work ''His expedition with the worthy Scot's regiment called Mac-k ...

to reinforce the authority of an admiral over his captains.

After the Battle of Dungeness in November 1652 the Dutch navy was in control of the English Channel through the winter of 1652–1653, allowing trade and commerce to once again resume. During this time, however, the English fleet had been refitted and reorganized, and by the beginning of February the English fleet numbered about eighty ships, which were promptly put into operation on 11 February under the joint command of the generals-at-sea Blake, Monck and Deane, setting the stage for the Battle of Portland. Blake's main objective was to intercept Lieutenant-Admiral Tromp, who was expected to escort a large merchant fleet from the Mediterranean to the Netherlands.

The English fleet was divided into three squadrons, the Red, Blue and White, each with its own vice- and rear-admirals which for the first time in British naval history established an ordered command hierarchy for the British Navy. Blake, aboard his flagship the

''Triumph'', was in command of the red squadron, with Monck in command of the Blue and Penn in command of the white. Clowes, 1897, v. II, pp. 178–179

Blake was informed that Tromp's fleet was approaching and was no more than forty leagues to the west.

Tromp had the great responsibility of getting his merchant convey home to safety, but when he learned that Blake was waiting for him in the channel, and that his fleet of warships was about the same size as Blake's fleet, and with the weather gage

The weather gage (sometimes spelled weather gauge or known as nautical gauge) is the advantageous position of a fighting sailing vessel relative to another. The concept is from the Age of Sail and is now antique. A ship at sea is said to possess ...

in his favor, he decided to take the initiative and move on Blake's fleet, leaving his convoy of merchant ships about four miles up wind.

While Blake's fleet had recently been outfitted with fresh supplies and ammunition, Tromp had been out at sea since November and was short of ammunition. Gardiner, 1897, v. II, p. 158

Knowing that Tromp's fleet and convoy of merchant ships had to pass his way to reach their destination, Blake was not compelled to go out searching for them. On 18 February the Dutch fleet of seventy-five ships came into Blake's view, but his squadrons had not yet grouped into their formations, having arrived there in haste at short notice. His red squadron was in position, but the White squadron was several miles to the east, while the Blue squadron was at some distance to the west, leaving Blake with about a dozen ships to face the entire Dutch fleet, which had the wind in their favor.

Tromp seized the advantageous opportunity and moved on Blake's lone squadron, and at eight in the morning a furious battle commenced. Subsequently Blake's squadron endured heavy damage and casualties, with 100 lives lost on the ''Triumph'', but the squadron was able to keep the Dutch fleet at bay. Capp, 1989, pp. 80–81 While the battle raged furiously, Blake was severely wounded in his thigh, while his flag-captain Andrew Ball was killed. Several hours would pass before Blake's other squadrons arrived at the scene. As Tromp's ships began to use up their supply of powder, they retreated from the engagement and headed for home, while the withdrawal of the remaining ships turned into a desperate flight for survival.

Thanks to its command of the sea, the fleet was able to supply Cromwell's army with provisions as it successfully marched on Scotland. By the end of 1652 the various English colonies in the Americas had also been secured.

At the Battle of the Gabbard

The Battle of the Gabbard, was a naval battle fought from 2 to 3 June 1653 during the First Anglo-Dutch War. It took place near the Gabbard shoal off the coast of Suffolk, England, between fleets of the Commonwealth of England and the Dutch Repu ...

on 12 and 13 June 1653 Blake reinforced the ships of Generals Richard Deane and George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle (6 December 1608 3 January 1670) was an English military officer and politician who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support ...

and decisively defeated the Dutch fleet, sinking or capturing 17 ships without losing one. Now also the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

was brought under English control, and the Dutch fleet was blockaded in various ports until the Battle of Scheveningen, where Tromp was killed.

Peace with the Dutch achieved, Blake sailed in October 1654 with 24 warships as commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

, successfully deterring the Duke of Guise

Count of Guise and Duke of Guise ( , ) were titles in the French nobility.

Originally a Fiefdom, seigneurie, in 1417 Guise was erected into a county for René I of Naples, René, a younger son of Louis II of Anjou.

While disputed by the House of ...

from conquering Naples. In 1656, the year before his death, Blake was appointed Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports is the name of a ceremonial post in the United Kingdom. The post dates from at least the 12th century, when the title was Keeper of the Coast, but it may be older. The Lord Warden was originally in charge of the ...

.

Bay of Tunis

In April 1655 Blake was selected by Cromwell to sail into theMediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

again to extract compensation from the Duke of Tuscany, the Knights of Malta

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta, and commonly known as the Order of Malta or the Knights of Malta, is a Catholic Church, Cathol ...

, and the piratical states of North Africa, that had been attacking English shipping. The Dey of Tunis was the only one who refused compensation, while also refusing to return captured British sailors held as slaves. Mirza, 1911, p. 36 Plant, 2010: BCW, Essay and further negotiations became futile. Blake, aboard his flagship ''George'', at first, needing to replenish water and other supplies, withdrew his fleet to Trapani

Trapani ( ; ; ) is a city and municipality (''comune'') with 54,887 inhabitants, on the west coast of Sicily, in Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Trapani. Founded by Elymians, the city is still an important fishing port and the mai ...

, leading the Dey to assume his fleet had retreated, and on 3 April 1655 he returned to Porto Farina. The following morning Blake, with fifteen ships, prepared for an attack on the castle and ships in the harbour which were protected by twenty cannon in the castle, along with other defensive works along the shore. During the assault Blake destroyed the two shore batteries and nine Algerian ships with continual cannon fire from Blake's ships, while the wind off the sea blew the intense smoke from the guns at the castle and into the town, obscuring the enemy's view. His crews boarded the ships docked in the harbour one at a time and set them ablaze, and within hours they were all reduced to scorched timber and ashes. With only twenty-five killed and forty wounded, it was the first time shore batteries had been neutralized without landing men ashore. Hoping that he had not exceeded his orders, Blake, upon submitting his report to Cromwell, found him most gracious and appreciative of his efforts. Laughton, 1907, p. 177 At this time Blake received orders to proceed off Cadiz, and carry on hostilities against Spain, with the objective of intercepting the Plate ships and to intercept reinforcements intended for Spanish forces in the West Indies.

Anglo-Spanish War

In February 1656 commercial rivalry with Spain was soon turned to war. In the Anglo-Spanish War Blake blockaded

In February 1656 commercial rivalry with Spain was soon turned to war. In the Anglo-Spanish War Blake blockaded Cádiz

Cádiz ( , , ) is a city in Spain and the capital of the Province of Cádiz in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. It is located in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula off the Atlantic Ocean separated fr ...

, during which one of his captains, Richard Stayner, destroyed most of the Spanish plate fleet at the Battle of Cádiz. A galleon of treasure was captured, and the overall loss to Spain was estimated at £2 million. Blake maintained the blockade throughout the winter, the first time the fleet had stayed at sea over winter.

On 20 April 1657 Blake totally destroyed another armed merchant convoy, the Spanish West Indian fleet, in the Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife—a port so well fortified that it was thought to be impregnable to attack from the sea—for the loss of just one ship. With expert marksmanship Blake's artillery successfully laid waste to most of the fort and destroyed or reduced the Spanish fleet to ashes. Although the silver had already been landed, Blake's victory delayed its arrival at the royal treasury of the Spanish government and earned the new English Navy respect throughout Europe. As a reward Blake was given an expensive diamond ring by Cromwell. The action also earned him respect 140 years later from Lord Nelson

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte ( – 21 October 1805) was a Royal Navy officer whose leadership, grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics brought about a number of decisive British naval victories during the French ...

who lost his arm there in a failed attack; in a letter written on 17 April 1797, to Admiral Sir John Jervis, Nelson wrote "I do not reckon myself equal to Blake", before going on to outline the plans for his own attack.

Final days and legacy

On 13 March 1655, Blake, still in active service while aboard the ''Naseby'', made out his last will and testament. The first item, consisting of a paragraph, began with, "I bequeath my soul unto the hands of my most merciful Redeemer, the Lord Jesus Christ..." He left the towns of Bridgwater and Taunton £100 each to be dispersed among the poor. He left his brother Humphrey his manor house, while leaving his other brothers considerable sums of money. Among other items bequeathed to other family members and friends, he left the gold chain that was awarded him by the Parliament to his nephew Robert, son of his deceased brother.

After again cruising off Cadiz for a while, Blake, aboard his flagship ''George'' turned for home, but on 7 August 1657 at ten o'clock in the morning he died of old wounds within sight of

On 13 March 1655, Blake, still in active service while aboard the ''Naseby'', made out his last will and testament. The first item, consisting of a paragraph, began with, "I bequeath my soul unto the hands of my most merciful Redeemer, the Lord Jesus Christ..." He left the towns of Bridgwater and Taunton £100 each to be dispersed among the poor. He left his brother Humphrey his manor house, while leaving his other brothers considerable sums of money. Among other items bequeathed to other family members and friends, he left the gold chain that was awarded him by the Parliament to his nephew Robert, son of his deceased brother.

After again cruising off Cadiz for a while, Blake, aboard his flagship ''George'' turned for home, but on 7 August 1657 at ten o'clock in the morning he died of old wounds within sight of Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

where a hero's welcome was planned for him. Dixon, 1852, pp. 360–363 Powell, 1972, p. 308 After lying in state

Lying in state is the tradition in which the body of a deceased official, such as a head of state, is placed in a state building, either outside or inside a coffin, to allow the public to pay their respects. It traditionally takes place in a ...

in the Queen's House

Queen's House is a former royal residence in the London borough of Greenwich, which presently serves as a public art gallery. It was built between 1616 and 1635 on the grounds of the now demolished Greenwich Palace, a few miles downriver fro ...

, Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

, he was given a full state funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive elements o ...

moved to Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

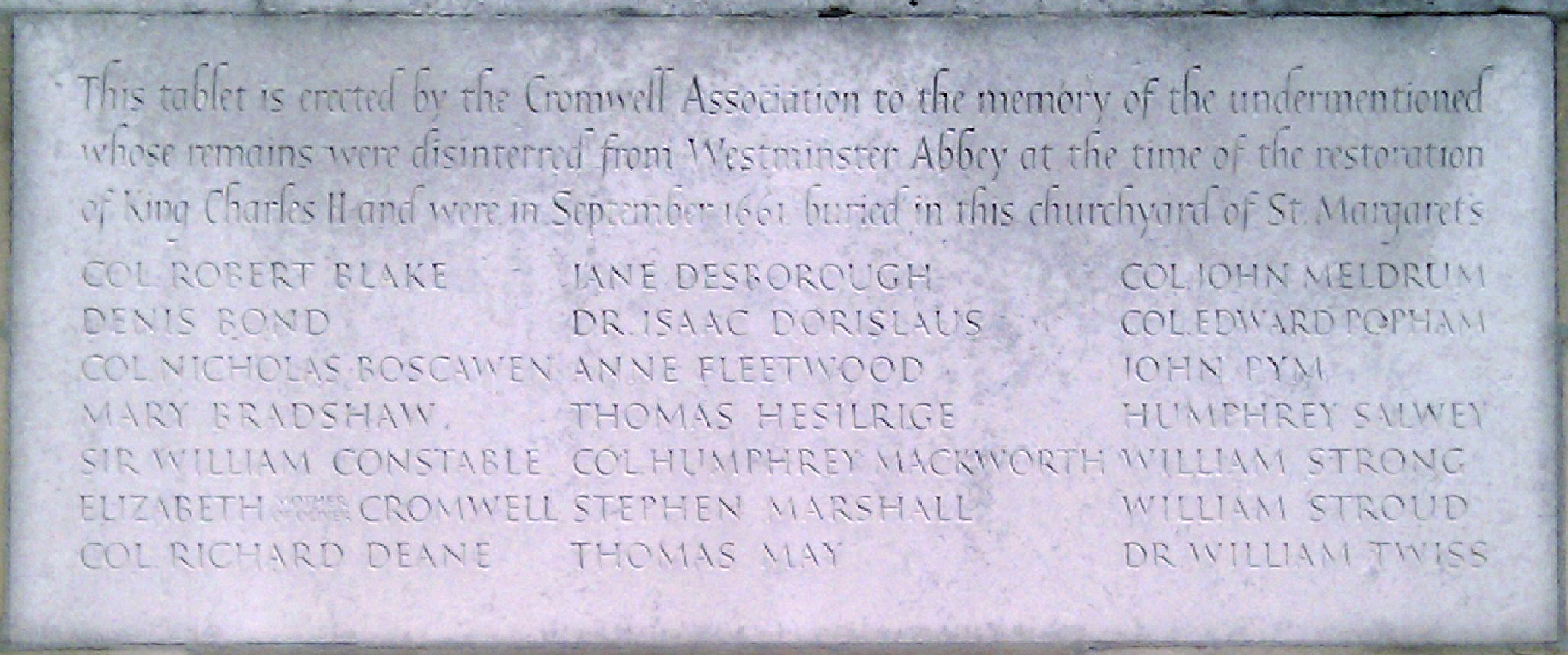

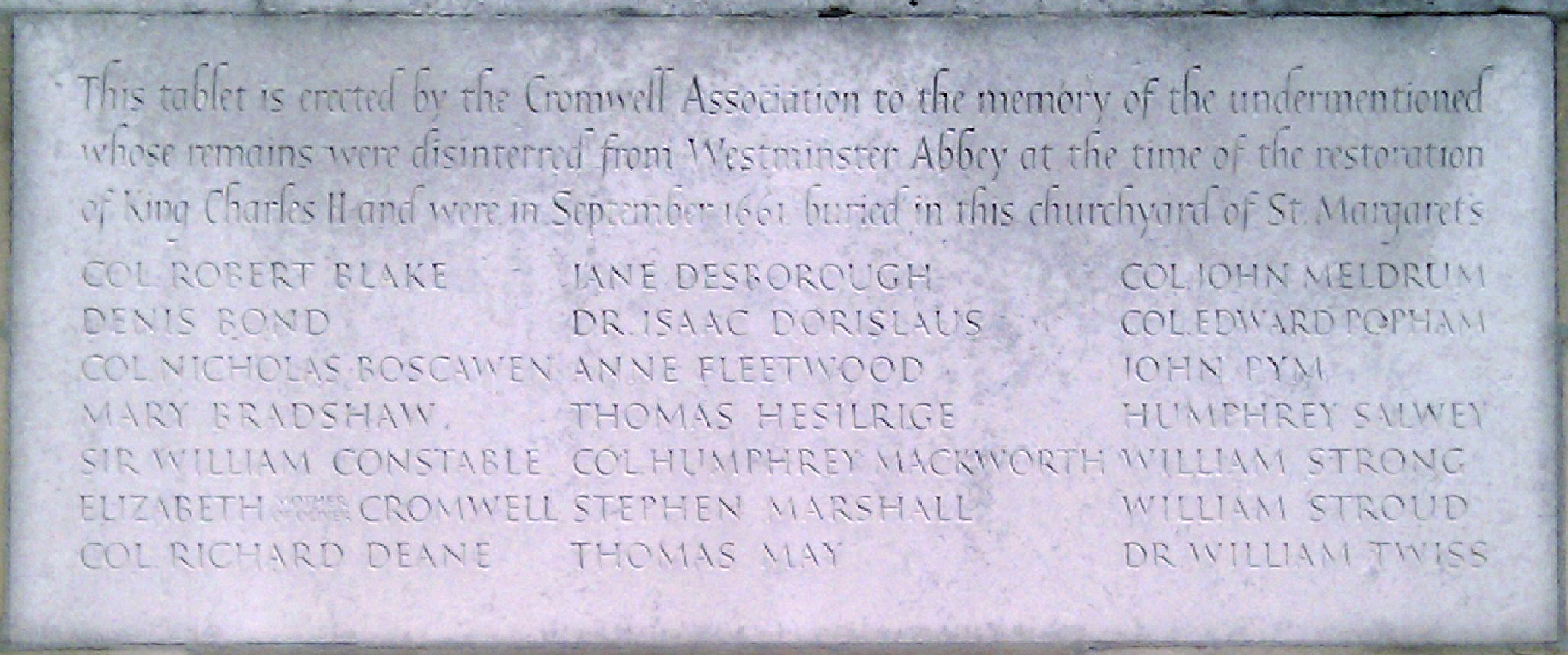

where the procession they were received by a military guard and saluted with salvoes of artillery before he was interred. Dixon, 1852, p. 364 Present at the ceremony were Oliver Cromwell and the members of the Council of State (although his internal organs had earlier been buried at St Andrew's Church, Plymouth). After the restoration of the Monarchy his body was exhumed in 1661 and placed in a common grave in St Margaret's churchyard, adjoining the Abbey, on the orders of the new king, Charles II.

In Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

, a stone memorial of Robert Blake, unveiled on 27 February 1945, can be found in the south choir aisle. St Margaret's Church, where Blake was reburied, has a stained-glass window depicting Blake's life, together with a brass plaque to his memory, unveiled on 18 December 1888. A modern stone memorial to Blake and the other Parliamentarians reburied in the churchyard has been set into the external wall to the left of the main entrance of the church.

In 1926 the house in Bridgwater, where it is believed that Blake was born, was purchased and turned into the Blake Museum, where a room is devoted to him and his exploits.

Blake is one of four maritime figures depicted with a statue on the facade of Deptford Town Hall, in the London Borough of Lewisham. Blake and his

In 1926 the house in Bridgwater, where it is believed that Blake was born, was purchased and turned into the Blake Museum, where a room is devoted to him and his exploits.

Blake is one of four maritime figures depicted with a statue on the facade of Deptford Town Hall, in the London Borough of Lewisham. Blake and his flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

''Triumph'' are featured on a second class postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail). Then the stamp is affixed to the f ...

issued in 1982.

In 2007 various events took place in Bridgwater, Somerset, from April to September to commemorate the 350th anniversary of the death of Robert Blake. These included a civic ceremony on 8 July 2007 and a 17th-century market on 15 July 2007. In the Royal Navy a series of ships have carried the name HMS ''Blake'' in honour of the general at sea.

As noted by one of Blake's biographers, Blake was responsible for the "... birth of a real British Navy ... Hitherto, expeditions had been entrusted to Court favourites, whose main inspiration was not patriotism, but gain; now, patriotism, not profit, was to be its watchword; glory, not gold, its

reward."

In Literature

Blake is the subject of a poetical illustration that recalls his exploits in byLetitia Elizabeth Landon

Letitia Elizabeth Landon (14 August 1802 – 15 October 1838) was an English poet and novelist, better known by her initials L.E.L.

Landon's writings are emblematic of the transition from Romanticism to Victorian literature. Her first major b ...

to an engraving by John Cochran after Briggs in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1837.

Relatives

Blake's brother, Benjamin Blake (1614–1689), served under Robert, emigrated to Carolina in 1682, and was the father of Joseph Blake, governor ofSouth Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

in 1694 and from 1696 to 1700.

Blake's brother Samual Blake fought under Popham before being killed in a duel in 1645.

A collateral relative was the historian Robert Blake, Baron Blake (1916–2003).

See also

*British ensign

In British maritime law and custom, an ensign is the identifying flag flown to designate a British ship, either military or civilian. Such flags display the United Kingdom Union Flag in the canton (the upper corner next to the staff), with eit ...

* Military history of the United Kingdom

* Glossary of nautical terms : (A–L), (M–Z)

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * Knight, Frank, (1971). ''General-at-Sea The Life of Admiral Robert Blake'' London Macdonald ** * * * * * * * * * * * * *

External links

The Blake Museum, Bridgwater

*

Admiral Blake

– Article in Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, 29 May 1852

Robert Blake, admiral and general at sea

William Hepworth Dixon

William Hepworth Dixon (30 June 1821 – 26 December 1879) was an English historian and traveller from Manchester. He was active in organizing London's Great Exhibition of 1851.

Early life

Dixon was born on 30 June 1821, at Great Ancoats in Manc ...

, 1852

{{DEFAULTSORT:Blake, Robert

Military personnel from Somerset

English admirals

English generals

Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports

Alumni of Wadham College, Oxford

People from Bridgwater

Burials at Westminster Abbey

1598 births

1657 deaths

Burials at St Margaret's, Westminster

17th-century English merchants

17th-century Royal Navy personnel

Royal Navy personnel of the First Anglo-Dutch War

English MPs 1640 (April)

English MPs 1653 (Barebones)

English MPs 1654–1655

English MPs 1656–1658

17th-century English businesspeople

Parliamentarian military personnel of the English Civil War

Lords of the Admiralty

People who died at sea