Adam Ferguson (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Adam Ferguson, (

Adam Ferguson, (

The ''Essay'' has been seen as an innovative attempt to reclaim the tradition of civic republican citizenship in modern Britain, and an influence on the ideas of

The ''Essay'' has been seen as an innovative attempt to reclaim the tradition of civic republican citizenship in modern Britain, and an influence on the ideas of

An Essay on the History of Civil Society

' (1767) ** Reprinted in 1995 with a new introduction by Louis Schneider. Transaction Publishers, London, 1995. *

The History of the Progress and Termination of the Roman Republic

' (1783) * ''Principles of Moral and Political Science; being chiefly a retrospect of lectures delivered in the College of Edinburgh'' (1792) *

Institutes of Moral Philosophy

' (1769) * ''Reflections Previous to the Establishment of a Militia'' (1756)

Reconsidering the Highland roots of Adam Ferguson by Denise Testa 2007.

Adam Ferguson

a

''The Online Library of Liberty''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ferguson, Adam 1723 births 1816 deaths 18th-century ministers of the Church of Scotland 18th-century Scottish Presbyterian ministers 18th-century Scottish historians Academics of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of the University of St Andrews British people of the War of the Austrian Succession Enlightenment philosophers Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Members of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences Natural philosophers People from Perth and Kinross Philosophers of culture Philosophers of economics Philosophers of history Philosophers of psychology Philosophers of religion Philosophers of war Scottish political philosophers Scottish essayists Scottish ethicists Scottish librarians Scottish military chaplains 18th-century Scottish philosophers 19th-century Scottish philosophers Scottish soldiers Social philosophers

Adam Ferguson, (

Adam Ferguson, (Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

: ''Adhamh MacFhearghais''), also known as Ferguson of Raith (1 July N.S. /20 June O.S. 1723 – 22 February 1816), was a Scottish philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human species; as well as the ...

of the Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment (, ) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century, Scotland had a network of parish schools in the Sco ...

.

Ferguson was sympathetic to traditional societies, such as the Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Africa

* Highlands, Johannesburg, South Africa

* Highlands, Harare, Zimbab ...

, for producing courage and loyalty. He criticized commercial society as making men weak, dishonourable and unconcerned for their community

A community is a social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant characteristic, such as place, set of norms, culture, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given g ...

. Ferguson has been called "the father of modern sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

" for his contributions to the early development of the discipline. His best-known work is his '' Essay on the History of Civil Society''.

Biography

Born atLogierait

Logierait () is a village and parish in Atholl, Scotland. It is situated at the confluence of the rivers Tay and Tummel, west of the A9 road in Perth and Kinross.

Its name originates from Gaelic , meaning the little hollow of the earth-walled ...

in Atholl

Atholl or Athole () is a district in the heart of the Scottish Highlands, bordering (in clockwise order, from north-east) Marr, Gowrie, Perth, Strathearn, Breadalbane, Lochaber, and Badenoch. Historically it was a Pictish kingdom, becoming ...

, Perthshire

Perthshire (Scottish English, locally: ; ), officially the County of Perth, is a Shires of Scotland, historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore, Angus and Perth & Kinross, Strathmore ...

, Scotland, the son of Rev Adam Ferguson, he received his education at Logierait Parish School, Perth Grammar School

Perth Grammar School is a secondary school in Perth, Scotland. It is located in the Muirton district of Perth at the junction of Bute Drive and Gowans Terrace. The catchment serves the area to the north of Perth between Murthly and Methven w ...

, and at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

and the University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, f ...

(MA 1742). In 1745, owing to his knowledge of Gaelic

Gaelic (pronounced for Irish Gaelic and for Scots Gaelic) is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". It may refer to:

Languages

* Gaelic languages or Goidelic languages, a linguistic group that is one of the two branches of the Insul ...

, he gained appointment as deputy chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intellige ...

of the 43rd (afterwards the 42nd) regiment (the Black Watch

The Black Watch, 3rd Battalion, Royal Regiment of Scotland (3 SCOTS) is an infantry battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland. The regiment was created as part of the Childers Reforms in 1881, when the 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment ...

), the licence to preach being granted him by special dispensation, although he had not completed the required six years of theological

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of an ...

study.

It remains a matter of debate as to whether, at the Battle of Fontenoy

The Battle of Fontenoy took place on 11 May 1745 during the War of the Austrian Succession, near Tournai, then in the Austrian Netherlands, now Belgium. A French army of 50,000 under Maurice, comte de Saxe, Marshal Saxe defeated a Pragmatic Ar ...

(1745), Ferguson fought in the ranks throughout the day, and refused to leave the field, though ordered to do so by his colonel. Nevertheless, he certainly did well, becoming principal chaplain in 1746. He continued attached to the regiment till 1754, when, disappointed at not obtaining a living, he left the clergy and resolved to devote himself to literary pursuits.

After residing in Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

for a time, he returned to Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

where in January 1757 he succeeded David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

as librarian to the Faculty of Advocates

The Faculty of Advocates () is an independent body of lawyers who have been admitted to practise as advocates before the courts of Scotland, especially the Court of Session and the High Court of Justiciary. The Faculty of Advocates is a const ...

(see Advocates' Library

The Advocates Library, founded in 1682, is the law library of the Faculty of Advocates, in Edinburgh. It served as the national deposit library of Scotland until 1925, at which time through an act of Parliament, the National Library of Scotland ...

), but soon relinquished this office on becoming tutor in the family of the Earl of Bute

Marquess of the County of Bute, shortened in general usage to Marquess of Bute, is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1796 for John Stuart, 4th Earl of Bute.

Family history

John Stuart was the member of a family that ...

. In 1759 Ferguson became professor of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

in the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

, and in 1764 transferred to the chair of "pneumatics" ( mental philosophy) and moral philosophy

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied et ...

.

In 1767, he published his '' Essay on the History of Civil Society'', which was well received and translated into several European languages

There are over 250 languages indigenous to Europe, and most belong to the Indo-European language family. Out of a total European population of 744 million as of 2018, some 94% are native speakers of an Indo-European language. The three larges ...

. In the mid-1770s he travelled again to the Continent

A continent is any of several large geographical regions. Continents are generally identified by convention (norm), convention rather than any strict criteria. A continent could be a single large landmass, a part of a very large landmass, as ...

and met Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

. His membership of The Poker Club

The Poker Club was one of several clubs at the heart of the Scottish Enlightenment where many associated with that movement met and exchanged views in a convivial atmosphere.

History

The Poker Club was created in 1762 out of the ashes of The ...

is recorded in its minute book of 1776.

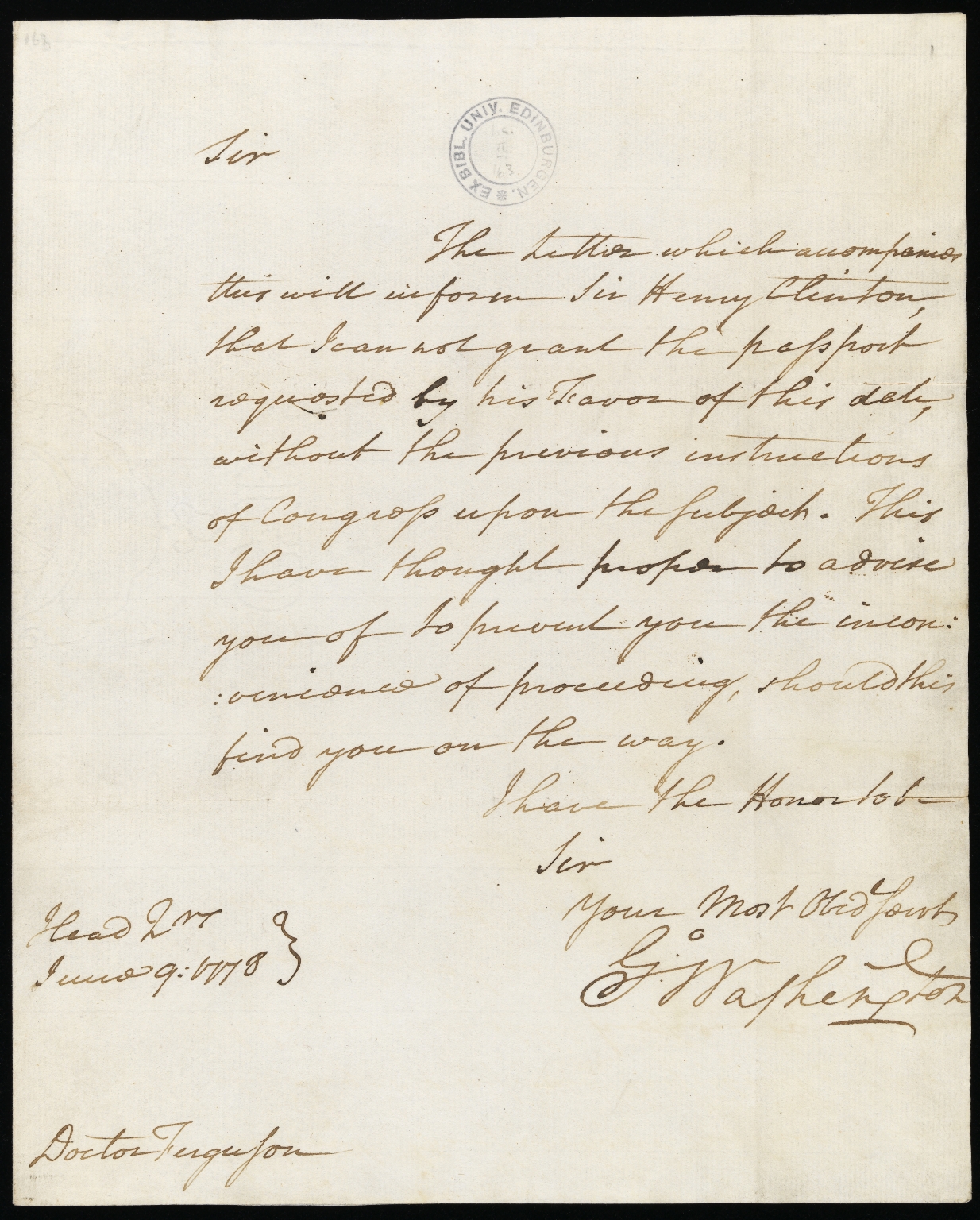

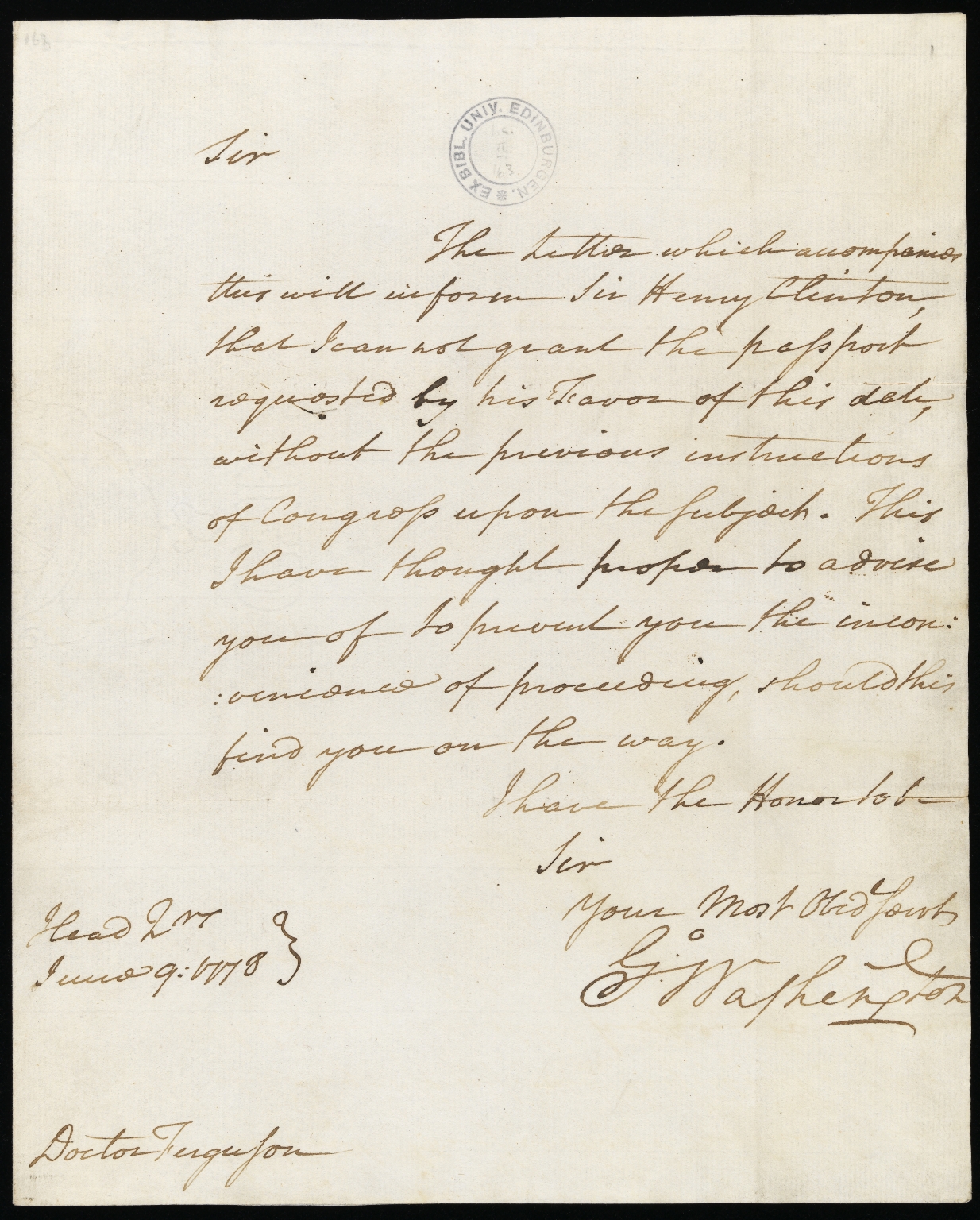

In 1776, appeared his anonymous pamphlet on the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

in opposition to Dr Richard Price

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer and pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the F ...

's '' Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty'', in which he sympathised with the views of the British legislature. In 1778 Ferguson was appointed secretary to the Carlisle Peace Commission

The Carlisle Peace Commission was a group of British peace commissioners who were sent to North America in 1778 to negotiate terms with the rebellious Continental Congress during the American Revolutionary War. The commission carried an offer of ...

which endeavoured, but without success, to negotiate an arrangement with the revolted colonies.

In 1780, he wrote the article "History" for the second edition of Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

. The article is 40 pages long and replaced the article in the first edition, which was only one paragraph.

In 1783, appeared his ''History of the Progress and Termination of the Roman Republic

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some theorists categ ...

'', it became very popular and went through several editions. Ferguson believed that the history of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

during the period of their greatness formed a practical illustration of those ethical and political doctrines which he studied especially. The history reads well and impartially, and displays conscientious use of sources. The influence of the author's military experience shows itself in certain portions of the narrative. Tired of teaching, he resigned his professorship in 1785, and devoted himself to the revision of his lectures, which he published (1792) under the title of '' Principles of Moral and Political Science''.

In his seventieth year, Ferguson, intending to prepare a new edition of the history, visited Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and some of the principal cities of Europe, where he was received with honour by learned societies

A learned society ( ; also scholarly, intellectual, or academic society) is an organization that exists to promote an academic discipline, profession, or a group of related disciplines such as the arts and sciences. Membership may be open to al ...

. From 1795 he resided successively at Neidpath Castle

Neidpath Castle is an L Plan Castle, L-plan rubble-built tower house, overlooking the River Tweed about west of Peebles in the Scottish Borders, Borders of Scotland. The castle is both a wedding venue and filming location and can be viewed by a ...

near Peebles

Peebles () is a town in the Scottish Borders, Scotland. It was historically a royal burgh and the county town of Peeblesshire. According to the United Kingdom census, 2011, 2011 census, the population was 8,376 and the estimated population in ...

, at Hallyards on Manor Water

Manor Water is a river in the parish of Manor, Peeblesshire in the Scottish Borders. It rises in the Ettrick Forest and flows down through the Maynor valley, passing the various farms and hamlets of Maynor as well as Kirkton Manynor, where the M ...

, and at St Andrews

St Andrews (; ; , pronounced ʰʲɪʎˈrˠiː.ɪɲ is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourth-largest settleme ...

, where he died on 22 February 1816. He is buried in the churchyard of St Andrews Cathedral

The Cathedral of St Andrew (often referred to as St Andrews Cathedral) is a ruined cathedral in St Andrews, Fife, Scotland. It was built in 1158 and became the centre of the Medieval Catholic Church in Scotland as the seat of the Archdiocese o ...

, against the east wall. His large mural monument includes a carved profile portrait in marble.

Ethics

In hisethical system

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied ethics ...

Ferguson treats man as a social being, illustrating his doctrines by political examples. As a believer in the progression of the human race

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are great apes characterized by their hairlessness, bipedalism, and high intelligenc ...

, he placed the principle of moral approbation in the attainment of perfection. Victor Cousin

Victor Cousin (; ; 28 November 179214 January 1867) was a French philosopher. He was the founder of " eclecticism", a briefly influential school of French philosophy that combined elements of German idealism and Scottish Common Sense Realism. ...

criticised Ferguson's speculations (see his ''Cours d'histoire de la philosophie morale an dix-huitième siècle'', pt. II., 1839–1840):

We find in his method the wisdom and circumspection of the Scottish school, with something more masculine and decisive in the results. The principle of perfection is a new one, at once more rational and comprehensive than benevolence and sympathy, which in our view places Ferguson as a moralist above all his predecessors.By this principle Ferguson attempted to reconcile all moral systems. With

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

and Hume

Hume most commonly refers to:

* David Hume (1711–1776), Scottish philosopher

Hume may also refer to:

People

* Hume (surname)

* Hume (given name)

* James Hume Nisbet (1849–1923), Scottish-born novelist and artist

In fiction

* Hume, t ...

he admits the power of self-interest or utility, and makes it enter into morals as the law of self-preservation. Francis Hutcheson's theory of universal benevolence and Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

's idea of mutual sympathy (now empathy

Empathy is generally described as the ability to take on another person's perspective, to understand, feel, and possibly share and respond to their experience. There are more (sometimes conflicting) definitions of empathy that include but are ...

) he combines under the law of society. But, as these laws appear as the means rather than the end of human destiny, they remain subordinate to a supreme end, and the supreme end of perfection.

In the political part of his system Ferguson follows Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal so ...

, and pleads the cause of well-regulated liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

and free government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

. His contemporaries, with the exception of Hume, regarded his writings as of great importance (see Sir Leslie Stephen, ''English Thought in the Eighteenth Century'', Cambridge University Press, 2011, p. 214). Ferguson shared his republican contemporaries' fear that imperial expansion would undermine the liberty of a state, but he saw representative institutions as a solution to the dangers posed by an expanding state. He defended the British Empire, but argued that political representation was key to prevent it from becoming tyrannical.

Social thought

Ferguson's ''An Essay on the History of Civil Society

''An Essay on the History of Civil Society'' is a book by Scottish Enlightenment philosopher Adam Ferguson, first published in 1767. The ''Essay'' established Ferguson's reputation in Britain and throughout Europe. In the second section of the ...

'' (1767) drew on classical authors and contemporary travel literature, to analyze modern commercial society with a critique of its abandonment of civic and communal virtues. Central themes in Ferguson's theory of citizenship are conflict, play, political participation and military valor. He emphasized the ability to put oneself in another's shoes, saying "fellow-feeling" was so much an "appurtenance of human nature" as to be a "characteristic of the species." Like his friends Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

and David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

as well as other Scottish intellectuals, he stressed the importance of the spontaneous order; that is, that coherent and even effective outcomes might result from the uncoordinated actions of many individuals.

Ferguson saw history as a two-tiered synthesis of natural history and social history, to which all humans belong. Natural history is created by God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

; so are humans, who are progressive. Social history is, in accordance with this natural progress, made by humans, and because of that factor it experiences occasional setbacks. But in general, humans are empowered by God to pursue progress in social history. Humans live not for themselves but for God's providential plan. He emphasized aspects of medieval chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric language, is an informal and varying code of conduct that developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It is associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood, with knights being members of ...

as ideal masculine

Masculinity (also called manhood or manliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles generally associated with men and boys. Masculinity can be theoretically understood as socially constructed, and there is also evidence that some beh ...

characteristics. British gentleman and young men were advised to dispense with aspects of politeness considered too feminine

Femininity (also called womanliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and Gender roles, roles generally associated with women and girls. Femininity can be understood as Social construction of gender, socially constructed, and there is also s ...

, such as the constant desire to please, and to adopt less superficial qualities that suggested inner virtue

A virtue () is a trait of excellence, including traits that may be morality, moral, social, or intellectual. The cultivation and refinement of virtue is held to be the "good of humanity" and thus is Value (ethics), valued as an Telos, end purpos ...

and courtesy

Courtesy (from the word , from the 12th century) is gentle politeness and courtly manners. In the Middle Ages in Europe, the behaviour expected of the nobility was compiled in courtesy books.

History

The apex of European courtly culture was ...

toward the 'fairer sex.'Kettler, ''The Social and Political Thought of Adam Ferguson'' (1965)Herman, A., The Scottish Enlightenment, Harper Perennial

Ferguson was a leading advocate of the Idea of Progress

Progress is movement towards a perceived refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. It is central to the philosophy of progressivism, which interprets progress as the set of advancements in technology, science, and social organization effic ...

. He believed that the growth of a commercial society through the pursuit of individual self-interest could promote a self-sustaining progress. Yet paradoxically Ferguson also believed that such commercial growth could foster a decline in virtue and thus ultimately lead to a collapse similar to Rome's. Ferguson, a devout Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

, resolved the apparent paradox by placing both developments in the context of a divinely ordained plan that mandated both progress and human free will. For Ferguson, the knowledge that humanity gains through its actions, even those actions resulting in temporary retrogression, form an intrinsic part of its progressive, asymptotic movement toward an ultimately unobtainable perfectibility.

Ferguson was influenced by classical humanism and such writers as Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

Tacitus’ two major historical works, ''Annals'' ( ...

, Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise '' The Prince'' (), writte ...

, and Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

. The fellow members of Edinburgh's Select Society

The Select Society, established in 1754 as The St. Giles Society but soon renamed, was an intellectual society in 18th century Edinburgh.Emerson, Roger L. ''The Social Composition of Enlightened Scotland: The Select Society of Edinburgh, 1754–1 ...

, which included David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

and Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, were also major influences. Ferguson believed that civilization is largely about laws that restrict our independence as individuals but provide liberty in the sense of security and justice. He warned that social chaos usually leads to despotism. The members of civil society give up their liberty-as-autonomy, which savages possess, in exchange for liberty-as-security, or civil liberty. Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal so ...

used a similar argument.

Smith emphasized capital accumulation

Capital accumulation is the dynamic that motivates the pursuit of profit, involving the investment of money or any financial asset with the goal of increasing the initial monetary value of said asset as a financial return whether in the form ...

as the driver of growth, but Ferguson suggested innovation and technical advance were more important, and he is therefore in some ways more in line with modern thinking. According to Smith, commerce tends to make men 'dastardly'. This foreshadows a theme Ferguson, borrowing freely from Smith, took up to criticize capitalism. Ferguson's critique of commercial society went far beyond that of Smith, and influenced Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

and Marx.

The ''Essay'' has been seen as an innovative attempt to reclaim the tradition of civic republican citizenship in modern Britain, and an influence on the ideas of

The ''Essay'' has been seen as an innovative attempt to reclaim the tradition of civic republican citizenship in modern Britain, and an influence on the ideas of republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

held by the American Founding Fathers.

Personal life

He married Katherine Burnett in 1767. Ferguson was first cousin, close friend and colleague to Joseph Black M.D and Katie Burnett was Black's niece. They produced seven children. The eldest,Adam Ferguson (British Army officer)

Sir Adam Ferguson (1770–1854) was deputy keeper of the regalia in Scotland.

Life

Ferguson was born on 21 December 1770, the first son of Professor Adam Ferguson and his wife Catherine Burnett niece to Joseph Black. He was elder brother to Capta ...

, was a close friend to Sir Walter Scott, followed by James, Joseph, John, Isabella, Mary and Margaret. John (John MacPherson Ferguson

John Macpherson Ferguson (1783–1855) was a Scot serving in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1823 mainly in command of HMS ''Mersey'', he rose to the rank of Rear Admiral. Life

He was born at Argyle Square in Edinburgh on 15 ...

) was a Rear Admiral in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

.

Ferguson suffered an attack of paralysis

Paralysis (: paralyses; also known as plegia) is a loss of Motor skill, motor function in one or more Skeletal muscle, muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory d ...

in 1780 but fully recovered and became a vegetarian

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the Eating, consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects as food, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slau ...

for the rest of his life. Ferguson also abstained from alcoholic drink. He did not dine out unless with his first cousin and great friend Joseph Black.

Main works

*An Essay on the History of Civil Society

' (1767) ** Reprinted in 1995 with a new introduction by Louis Schneider. Transaction Publishers, London, 1995. *

The History of the Progress and Termination of the Roman Republic

' (1783) * ''Principles of Moral and Political Science; being chiefly a retrospect of lectures delivered in the College of Edinburgh'' (1792) *

Institutes of Moral Philosophy

' (1769) * ''Reflections Previous to the Establishment of a Militia'' (1756)

References

*Sources

* * Articles in ''Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

''

*

*

* Hill, Lisa. "Adam Ferguson and the Paradox of Progress and Decline," ''History of Political Thought'' 1997 18(4): 677–706

* Kettler, David ''Adam Ferguson: His Social and Political Thought.'' New Brunswick: Transaction, 2005.

* McDaniel, Iain. ''Adam Ferguson in the Scottish Enlightenment: The Roman Past and Europe's Future'' (Harvard University Press; 2013) 276 pages

* McCosh, James, ''The Scottish philosophy, biographical, expository, critical, from Hutcheson to Hamilton'' (1875)

* Oz-Salzberger, Fania. "Introduction" in ''Adam Ferguson, An Essay on the History of Civil Society,'' edited by F. Oz-Salzberger, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995

* Oz-Salzberger, Fania. ''Translating the Enlightenment: Scottish Civic Discourse in Eighteenth-Century Germany,'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995)

* Vileisis, Danga: ''Der unbekannte Beitrag Adam Fergusons zum materialistischen Geschichtsverständnis von Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

''. In: ''Beiträge zur Marx-Engels-Forschung. Neue Folge 2009''. Argument Verlag, Hamburg 2010, S. 7–60

* "Adam Ferguson" ''Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The ''Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' is an encyclopedia of philosophy edited by Edward Craig that was first published by Routledge in 1998. Originally published in both 10 volumes of print and as a CD-ROM, in 2002 it was made available on ...

'' 1998

* Waszek, Norbert & Hauck, Eveline. ""In the human kind, the species has a progress as well as the individual": Adam Ferguson on the progress of "mankind"", in: ''Humankind and Humanity in the Philosophy of the Enlightenment'', ed. by Stefanie Buchenau & Ansgar Lyssy, London, Bloomsbury, 2023, p. 115–130.

Further reading

* Broadie, Alexander, ed. ''The Scottish Enlightenment: An Anthology'' (2001).Reconsidering the Highland roots of Adam Ferguson by Denise Testa 2007.

External links

* *Adam Ferguson

a

''The Online Library of Liberty''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ferguson, Adam 1723 births 1816 deaths 18th-century ministers of the Church of Scotland 18th-century Scottish Presbyterian ministers 18th-century Scottish historians Academics of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of the University of St Andrews British people of the War of the Austrian Succession Enlightenment philosophers Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Members of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences Natural philosophers People from Perth and Kinross Philosophers of culture Philosophers of economics Philosophers of history Philosophers of psychology Philosophers of religion Philosophers of war Scottish political philosophers Scottish essayists Scottish ethicists Scottish librarians Scottish military chaplains 18th-century Scottish philosophers 19th-century Scottish philosophers Scottish soldiers Social philosophers