Acclimatization Society on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Acclimatisation societies were

The British acclimatisation society originated from an idea proposed by the management of '' The Field'' magazine. A meeting was held on 21 January 1859, at the

The British acclimatisation society originated from an idea proposed by the management of '' The Field'' magazine. A meeting was held on 21 January 1859, at the

''New Scientist'' review of ''They Dined on Eland: The Story of the Acclimatisation Societies'' by Christopher Lever,(1993)Bulletin de la Société impériale zoologique d'acclimatation (French)

* {{Authority control Defunct organizations Horticultural organizations

voluntary association

A voluntary group or union (also sometimes called a voluntary organization, common-interest association, association, or society) is a group of individuals who enter into an agreement, usually as volunteers, to form a body (or organization) to a ...

s, founded in the 19th and 20th centuries, that encouraged the introduction of non-native species in various places around the world, in the hope that they would acclimatise and adapt to their new environments. The societies formed during the colonial era, when Europeans began to settle in numbers in unfamiliar locations. One motivation for the activities of the acclimatisation societies was that introducing new species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s and animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

s (mainly from Europe) would enrich the flora

Flora (: floras or florae) is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. The corresponding term for animals is ''fauna'', and for f ...

and fauna

Fauna (: faunae or faunas) is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding terms for plants and fungi are ''flora'' and '' funga'', respectively. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively ...

of target regions. The movement also sought to establish plants and animals that were familiar to Europeans, while also bringing exotic and useful foreign plants and animals to centres of European settlement.

It is now widely understood that introducing species to foreign environments is often harmful to native species

In biogeography, a native species is indigenous to a given region or ecosystem if its presence in that region is the result of only local natural evolution (though often popularised as "with no human intervention") during history. The term is equi ...

and to their ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

s. For example, in Australia the environment was seriously harmed by overgrazing by rabbits. In North America house sparrows displaced and killed native birds. In New Zealand, introduced mammals such as possum

Possum may refer to:

Animals

* Didelphimorphia, or (o)possums, an order of marsupials native to the Americas

** Didelphis, a genus of marsupials within Didelphimorphia

*** Common opossum, native to Central and South America

*** Virginia opossum ...

s and cats

The cat (''Felis catus''), also referred to as the domestic cat or house cat, is a small domesticated carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species of the family Felidae. Advances in archaeology and genetics have shown that the ...

became threats to indigenous plants, birds and lizards. Around the world, salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All t ...

populations are threatened by introduced fungal infections

Fungal infection, also known as mycosis, is Infection, a disease caused by pathogenic fungi, fungi. Different types are traditionally divided according to the part of the body affected: superficial, subcutaneous tissue, subcutaneous, and system ...

. Consequently, the deliberate introduction of new species is now illegal in some countries.

Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

attempted to define acclimatisation in his contribution on the subject in the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 11th edition (1911). Wallace tried to differentiate the concept from other terms, such as "domestication" and "naturalisation". He noted that a domesticated animal could live in environments controlled by humans. Naturalisation, he suggested, included the process of acclimatisation, which involved "gradual adjustment". The idea, at least in France, was associated with Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

, and Wallace noted that some, such as Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, denied the possibility of forcing individual animals to adjust. However, Wallace pointed out that there was the possibility that there were variations among individuals and so some could have the ability to adapt to new environments.

In France

The first acclimatisation society was ''La Societé Zoologique d'Acclimatation'', founded inParis

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

by Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (; 16 December 1805 – 10 November 1861) was a French zoologist and an authority on deviation from normal structure. In 1854 he coined the term ''éthologie'' (ethology).

Biography

He was born in Paris, the ...

, on 10 May 1854. It was essentially an offshoot of the National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. With 4.4 ...

in Paris, and the other staff included Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages, Antoine César Becquerel and his son Alexandre. Saint-Hilaire subscribed to the Lamarckian idea that humans and animals could be forced to adapt to new environments. The French society established a branch in Algeria, as well as the '' Jardin d' Acclimatation'' in Paris in 1861, to showcase not just new animals and plants but also people from other lands.

Rewards in the form of medals were offered for anyone in the colonies who established breeding animals. The rules were that at least six specimens had to be maintained, with at least two instances of breeding in captivity. After Saint-Hilaire's death in 1861, the Society was headed by Édouard Drouyn de Lhuys

Édouard Drouyn de Lhuys (; 19 November 1805 – 1 March 1881) was a French diplomat. Born in Paris, he was educated at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand. The scion of a wealthy and noble house, he excelled in rhetoric. He quickly became interested ...

, foreign minister to Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

, and many of the functionaries were diplomats who established ties with officers in the colonies both French and foreign. Franco-British as well as Franco-Australian ties were involved in the movements of plants and animals. Australian acacias, for instance, were introduced in Algeria by the French, and by the British in South Africa. François Laporte, naturalist and consul in Melbourne, and Ferdinand von Mueller

Baron Sir Ferdinand Jacob Heinrich von Mueller, (; 30 June 1825 – 10 October 1896) was a German-Australian physician, geographer, and most notably, a botanist. He was appointed government botanist for the then colony of Victoria, Australia ...

of the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria, were involved in the transfer of many plant species out of Australia. In some cases, those movements were not direct but via Paris and Kew.

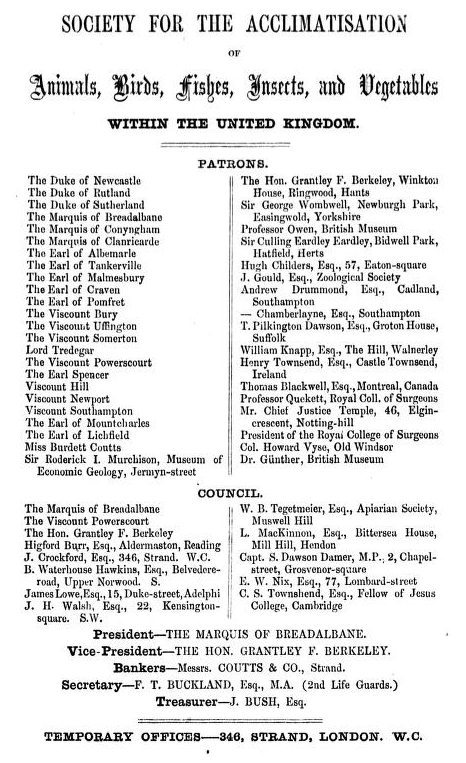

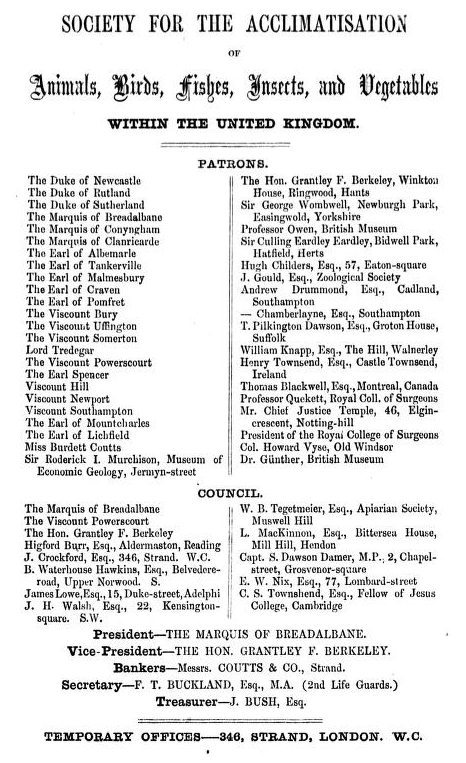

In Britain

The British acclimatisation society originated from an idea proposed by the management of '' The Field'' magazine. A meeting was held on 21 January 1859, at the

The British acclimatisation society originated from an idea proposed by the management of '' The Field'' magazine. A meeting was held on 21 January 1859, at the London Tavern

The City of London Tavern or London Tavern was a notable meeting place in London during the 18th and 19th centuries. A place of business where people gathered to drink alcoholic beverages and be served food, the tavern was situated in Bishopsgate ...

on Bishopsgate Street. The attendees included Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

at the head of the table, and the servings included a large pike, American partridge

A partridge is a medium-sized Galliformes, galliform bird in any of several genera, with a wide Indigenous (ecology), native distribution throughout parts of Europe, Asia and Africa. Several species have been introduced to the Americas. They ar ...

s, a young bean goose

The bean goose is a species complex of goose that breeds in northern Europe and Palearctic, Eurosiberia. It has at least two distinct varieties, one inhabiting taiga habitats and one inhabiting tundra. These are recognised as separate species by ...

and an African eland. At the meeting, Mitchell and others suggested that many of those exotic animals could live in the British wilderness. A few days later, Owen wrote to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'', praising the taste of the eland and advocating animal introductions.

On 26 June 1860, another meeting was held and the Acclimatisation Society was formally founded in London. A year later, the Secretary to the Society, Frank Buckland, a popular naturalist known for his taste in exotic meats, noted the "success" of the Society in introducing peafowl

Peafowl is a common name for two bird species of the genus '' Pavo'' and one species of the closely related genus '' Afropavo'' within the tribe Pavonini of the family Phasianidae (the pheasants and their allies). Male peafowl are referred t ...

, common pheasant, European swans, starling

Starlings are small to medium-sized passerine (perching) birds known for the often dark, glossy iridescent sheen of their plumage; their complex vocalizations including mimicking; and their distinctive, often elaborate swarming behavior, know ...

s and linnets into Australia, through the efforts of Edward Wilson. One of the supporters of the Society was Burdett Coutts. Other such societies spread quickly around the world, particularly to European colonies in the Americas, Australia and New Zealand. In many instances they existed both as societies for the study of natural history as well as to improve the success rate of introduced species. In 1850, English sparrows were introduced into America, and Eugene Schieffelin

Eugene Schieffelin (January 29, 1827 – August 15, 1906) was an American amateur ornithologist who belonged to the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society and the New York Zoological Society. In 1877, he became chairman of the American Ac ...

introduced starlings in 1890.

Australia and New Zealand

The appeal of acclimatisation societies in colonies, particularly Australia and New Zealand, was the belief that the local fauna was in some way deficient or impoverished. There was also an element of nostalgia in the desire of European colonists to see familiar species. An Australian settler, J. Martin, complained in 1830 that the "trees retained their leaves and shed their bark instead, the swans were black, the eagles white, the bees were stingless, some mammals had pockets, others laid eggs, it was warmest on the hills..." It was there that the desire to make the land feel more like England was strongest. The Acclimatisation Society of Victoria was established in 1861. Speaking to the Society, George Bennett pointed out how it was important to have such an organisation, citing the example of the Earl of Knowsley, who had been conducting successful experiments in private, the results of which had been lost with his death. A major proponent of importing and exporting trees and plants wasFerdinand von Mueller

Baron Sir Ferdinand Jacob Heinrich von Mueller, (; 30 June 1825 – 10 October 1896) was a German-Australian physician, geographer, and most notably, a botanist. He was appointed government botanist for the then colony of Victoria, Australia ...

. Introductions of commercially valuable species or game species were also made. In some instances, the results were disastrous, such as the economic and ecological disaster of introducing rabbits to Australia or possums to New Zealand. The dire effects were rapidly felt and a Rabbit Nuisance Act was passed in New Zealand in 1876. To make matters worse, there was a suggestion that weasels and stoats should be imported to control the rabbits. Despite warnings from Alfred Newton

Alfred Newton Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS HFRSE (11 June 18297 June 1907) was an England, English zoologist and ornithologist. Newton was Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Cambridge University from 1866 to 1907. Among his numerous public ...

and others, the predators were introduced, and Herbert Guthrie-Smith declared it as an "attempt to correct a blunder by a crime."

In 1893, T. S. Palmer of California wrote about the dangers of animal introduction. In 1906, the editors of the Avicultural Magazine were decidedly against the idea of bird introductions. The emergence of the field of ecology

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their Natural environment, environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosystem, and biosphere lev ...

transformed expert and public opinion on introductions and gave way to new rules. Quarantine regulations began to be set up instead. Beginning in New Zealand, some of the acclimatisation societies transformed themselves into fish and game organisations.

See also

*Introduced species

An introduced species, alien species, exotic species, adventive species, immigrant species, foreign species, non-indigenous species, or non-native species is a species living outside its native distributional range, but which has arrived ther ...

*Invasive species

An invasive species is an introduced species that harms its new environment. Invasive species adversely affect habitats and bioregions, causing ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage. The term can also be used for native spec ...

*Assisted migration

Assisted migration is "the intentional establishment of populations or meta-populations beyond the boundary of a species' historic range for the purpose of tracking suitable habitats through a period of changing climate...." It is therefore a na ...

*Acclimatisation societies in New Zealand

__NOTOC__

acclimatisation society, Acclimatisation societies to naturalise all kinds of new species —as long as they had no harmful effect— were established in New Zealand by European colonists from the 1860s, with the first likely having b ...

*American Acclimatization Society

The American Acclimatization Society was a group founded in New York City in 1871 dedicated to introducing European flora and fauna into North America for both economic and cultural reasons. The group's charter explained its goal was to introduce ...

*Queensland Acclimatisation Society

The Queensland Acclimatisation Society (QAS) was an acclimatisation society based in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia which operated from 1862 to 1956. Its primary interest was in the introduction of exotic plants, particularly tropical and sub-tr ...

* South Australian Acclimatization and Zoological Society

References

External links

''New Scientist'' review of ''They Dined on Eland: The Story of the Acclimatisation Societies'' by Christopher Lever,(1993)

* {{Authority control Defunct organizations Horticultural organizations