Acanthocephala Terminalis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Acanthocephala (

Several morphological characteristics distinguish acanthocephalans from other phyla of parasitic worms.

Several morphological characteristics distinguish acanthocephalans from other phyla of parasitic worms.

Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving a number of hosts, for both

Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving a number of hosts, for both

Having been expelled by the female, the acanthocephalan egg is released along with the feces of the host. For development to occur, the egg, containing the acanthor, needs to be ingested by an

Having been expelled by the female, the acanthocephalan egg is released along with the feces of the host. For development to occur, the egg, containing the acanthor, needs to be ingested by an

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, ' 'thorn' + , ' 'head') is a group of parasitic worm

Parasitic worms, also known as helminths, are a polyphyletic group of large macroparasites; adults can generally be seen with the naked eye. Many are intestinal worms that are soil-transmitted and infect the gastrointestinal tract. Other par ...

s known as acanthocephalans, thorny-headed worms, or spiny-headed worms, characterized by the presence of an eversible proboscis

A proboscis () is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular arthropod mouthparts, mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a pr ...

, armed with spines, which it uses to pierce and hold the gut wall of its host. Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving at least two hosts, which may include invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s, fish, amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s, birds, and mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s. About 1,420 species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

have been described.

The Acanthocephala were long thought to be a discrete phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

. Recent genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

analysis has shown that they are descended from, and should be considered as, highly modified rotifer

The rotifers (, from Latin 'wheel' and 'bearing'), sometimes called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic Coelom#Pseudocoelomates, pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first describ ...

s. This unified taxon is sometimes known as Syndermata

Syndermata is a clade of animals that, in some systems, is considered synonymous with Rotifera. Older systems separate Rotifera and Acanthocephala as different phyla, and group them both under Syndermata., p. 788ff. – see particularly p. 804 ...

, or simply as Rotifera, with the acanthocephalans described as a subclass of a rotifer class Hemirotatoria.

History

The earliest recognisable description of Acanthocephala – a worm with a proboscis armed with hooks – was made by Italian authorFrancesco Redi

Francesco Redi (18 February 1626 – 1 March 1697) was an Italians, Italian physician, naturalist, biologist, and poet. He is referred to as the "founder of experimental biology", and as the "father of modern parasitology". He was the first perso ...

(1684). In 1771, Joseph Koelreuter

Joseph is a common male name, derived from the Hebrew (). "Joseph" is used, along with " Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the modern-day Nordic count ...

proposed the name Acanthocephala. Philipp Ludwig Statius Müller

Philipp Ludwig Statius Müller (25 April 1725 – 5 January 1776) was a German zoologist.

Statius Müller was born in Esens, and was a professor of natural science at Erlangen. Between 1773 and 1776, he published a German translation of Linnaeus' ...

independently called them ''Echinorhynchus'' in 1776. Karl Rudolphi

Karl Asmund Rudolphi (14 July 1771 – 29 November 1832) was a Swedish-born German naturalist, who is credited with being the "father of helminthology".

Life

Rudolphi was born in Stockholm to German parents. He was awarded his PhD in 1793 ...

in 1809 formally named them Acanthocephala.

Evolutionary history

The oldest known member of the group is theMiddle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second Epoch (geology), epoch of the Jurassic Period (geology), Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 161.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relativel ...

(living approximately 165 million years ago) taxon '' Juracanthocephalus daohugouensis'' known from the Jiulongshan Formation

The Haifanggou Formation (), also known as the Jiulongshan Formation (), is a fossil-bearing rock deposit located near Daohugou () village of Ningcheng County, in Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

The formation consists of coarse Conglomerate ( ...

(China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

). The fossil record of the group also includes eggs found in a coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name ...

from the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

Bauru Group of Brazil, around 70–80 million years old, likely from a crocodyliform

Crocodyliformes is a clade of Crurotarsi, crurotarsan archosaurs, the group often traditionally referred to as "crocodilians". They are the first members of Crocodylomorpha to possess many of the features that define later relatives. They are the ...

. The group may have originated substantially earlier.

Phylogeny

Acanthocephalans are highly adapted to a parasitic mode of life, and have lost many organs and structures through evolutionary processes. This makes determining relationships with other higher taxa through morphological comparison problematic. A 2016phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical dat ...

analysis of the gene order in the mitochondria suggests that Seisonidea and Acanthocephala are sister clades and that the Eurotatoria are the sister clade to this group, producing the cladogram below.

Morphology

Several morphological characteristics distinguish acanthocephalans from other phyla of parasitic worms.

Several morphological characteristics distinguish acanthocephalans from other phyla of parasitic worms.

Digestion

Acanthocephalans lack a mouth oralimentary canal

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. ...

. This is a feature they share with the cestoda

Cestoda is a class of parasitic worms in the flatworm phylum (Platyhelminthes). Most of the species—and the best-known—are those in the subclass Eucestoda; they are ribbon-like worms as adults, commonly known as tapeworms. Their bodies co ...

(tapeworms), although the two groups are not closely related. Adult stages live in the intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. T ...

s of their host and uptake nutrients which have been digested

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food compounds into small water-soluble components so that they can be absorbed into the blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intestine into th ...

by the host, directly, through their body surface. The acanthocephalans lack an excretory system, although some species have been shown to possess flame cell

A flame cell is a specialized excretory cell found in simple invertebrates, including flatworms ( Platyhelminthes), rotifers and nemerteans; these are the simplest animals to have a dedicated excretory system. Flame cells function like a kidney ...

s (protonephridia).

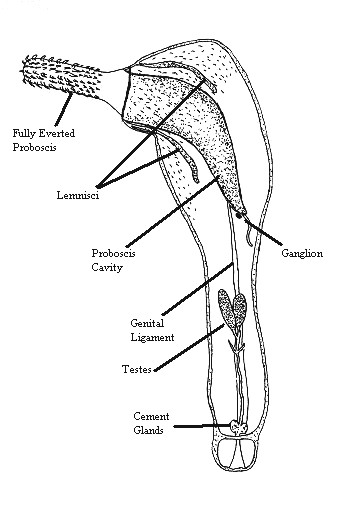

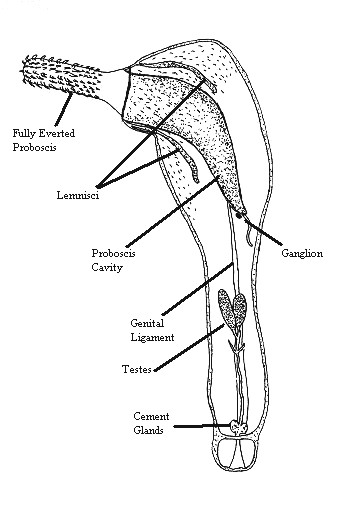

Proboscis

The most notable feature of the acanthocephala is the presence of ananterior

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

, protrudable proboscis

A proboscis () is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular arthropod mouthparts, mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a pr ...

that is usually covered with spiny hooks (hence the common name: thorny or spiny headed worm). The proboscis bears rings of recurved hooks arranged in horizontal rows, and it is by means of these hooks that the animal attaches itself to the tissues of its host. The hooks may be of two or three shapes, usually: longer, more slender hooks are arranged along the length of the proboscis, with several rows of more sturdy, shorter nasal hooks around the base of the proboscis. The proboscis is used to pierce the gut wall of the final host, and hold the parasite fast while it completes its life cycle.

Like the body, the proboscis is hollow, and its cavity is separated from the body cavity by a ''septum'' or ''proboscis sheath''. Traversing the cavity of the proboscis are muscle

Muscle is a soft tissue, one of the four basic types of animal tissue. There are three types of muscle tissue in vertebrates: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle. Muscle tissue gives skeletal muscles the ability to muscle contra ...

-strands inserted into the tip of the proboscis at one end and into the septum at the other. Their contraction causes the proboscis to be invaginated into its cavity. The whole proboscis apparatus can also be, at least partially, withdrawn into the body cavity, and this is effected by two retractor muscles which run from the posterior aspect of the septum to the body wall.

Some of the acanthocephalans (perforating acanthocephalans) can insert their proboscis in the intestine of the host and open the way to the abdominal cavity.

Size

The size of these animals varies greatly, ranging from a few millimetres in length to ''Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus

''Macracanthorhynchus'', also known as the giant thorny-headed worm of swine, is a member of the Oligacanthorhynchidae which contains four species. Taxonomy

Phylogenetic analysis has been conducted on at least one of the four species in the gen ...

'', which measures from . A curious feature shared by both larva and adult is the large size of many of the cells, e.g. the nerve cells and cells forming the uterine bell. Polyploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the biological cell, cells of an organism have more than two paired sets of (Homologous chromosome, homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have Cell nucleus, nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning ...

y is common, with up to 343n having been recorded in some species.

Skin

The body surface of the acanthocephala is peculiar. Externally, the skin has a thin tegument covering theepidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and Subcutaneous tissue, hypodermis. The epidermal layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the ...

, which consists of a syncytium

A syncytium (; : syncytia; from Greek: σύν ''syn'' "together" and κύτος ''kytos'' "box, i.e. cell") or symplasm is a multinucleate cell that can result from multiple cell fusions of uninuclear cells (i.e., cells with a single nucleus), i ...

with no cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

s. The syncytium is traversed by a series of branching tubule

In biology, a tubule is a general term referring to small tube or similar type of structure. Specifically, tubule can refer to:

* a small tube or fistular structure

* a minute tube lined with glandular epithelium

* any hollow cylindrical body stru ...

s containing fluid and is controlled by a few wandering, amoeboid

An amoeba (; less commonly spelled ameba or amœba; : amoebas (less commonly, amebas) or amoebae (amebae) ), often called an amoeboid, is a type of cell or unicellular organism with the ability to alter its shape, primarily by extending and r ...

nuclei. Inside the syncytium is an irregular layer of circular muscle fibres, and within this again some rather scattered longitudinal fibres; there is no endothelium

The endothelium (: endothelia) is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the r ...

. In their micro-structure the muscular fibres resemble those of nematode

The nematodes ( or ; ; ), roundworms or eelworms constitute the phylum Nematoda. Species in the phylum inhabit a broad range of environments. Most species are free-living, feeding on microorganisms, but many are parasitic. Parasitic worms (h ...

s.

Except for the absence of the longitudinal fibres the skin of the proboscis resembles that of the body, but the fluid-containing tubules of the proboscis are shut off from those of the body. The canals of the proboscis open into a circular vessel which runs round its base. From the circular canal two sac-like projections called the ''lemnisci'' run into the cavity of the body, alongside the proboscis cavity. Each consists of a prolongation of the syncytial material of the proboscis skin, penetrated by canals and sheathed with a muscular coat. They seem to act as reservoirs into which the fluid which is used to keep the proboscis "erect" can withdraw when it is retracted, and from which the fluid can be driven out when it is wished to expand the proboscis.

Nervous system

The central ganglion of the nervous system lies behind the proboscis sheath or septum. It innervates the proboscis and projects two stout trunks posteriorly which supply the body. Each of these trunks is surrounded by muscles, and this nerve-muscle complex is called a ''retinaculum''. In the male at least there is also agenital

A sex organ, also known as a reproductive organ, is a part of an organism that is involved in sexual reproduction. Sex organs constitute the primary sex characteristics of an organism. Sex organs are responsible for producing and transporting ...

ganglion

A ganglion (: ganglia) is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system, this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system, there are ...

. Some scattered papillae may possibly be sense-organs.

Life cycles

Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving a number of hosts, for both

Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving a number of hosts, for both developmental

Development of the human body is the process of growth to maturity. The process begins with fertilization, where an egg released from the ovary of a female is penetrated by a sperm cell from a male. The resulting zygote develops through mitosis ...

and resting stages. Complete life cycles have been worked out for only 25 species.

Reproduction

The Acanthocephala aredioecious

Dioecy ( ; ; adj. dioecious, ) is a characteristic of certain species that have distinct unisexual individuals, each producing either male or female gametes, either directly (in animals) or indirectly (in seed plants). Dioecious reproduction is ...

(an individual organism is either male or female). There is a structure called the ''genital ligament'' which runs from the posterior end of the proboscis sheath to the posterior end of the body. In the male, two testes

A testicle or testis ( testes) is the gonad in all male bilaterians, including humans, and is homologous to the ovary in females. Its primary functions are the production of sperm and the secretion of androgens, primarily testosterone.

The ...

lie on either side of this. Each opens in a vas deferens

The vas deferens (: vasa deferentia), ductus deferens (: ductūs deferentes), or sperm duct is part of the male reproductive system of many vertebrates. In mammals, spermatozoa are produced in the seminiferous tubules and flow into the epididyma ...

which bears three diverticula

In medicine or biology, a diverticulum is an outpouching of a hollow (or a fluid-filled) structure in the body. Depending upon which layers of the structure are involved, diverticula are described as being either true or false.

In medicine, t ...

or ''vesiculae seminales''. The male also possesses three pairs of cement glands, found behind the testes, which pour their secretions through a duct into the vasa deferentia. These unite and end in a penis

A penis (; : penises or penes) is a sex organ through which male and hermaphrodite animals expel semen during copulation (zoology), copulation, and through which male placental mammals and marsupials also Urination, urinate.

The term ''pen ...

which opens posteriorly.

In the female, the ovaries

The ovary () is a gonad in the female reproductive system that produces ova; when released, an ovum travels through the fallopian tube/oviduct into the uterus. There is an ovary on the left and the right side of the body. The ovaries are endocr ...

are found, like the testes, as rounded bodies along the ligament. From the ovaries, masses of ova

, abbreviated as OVA and sometimes as OAV (original animation video), are Japanese animated films and special episodes of a series made specially for release in home video formats without prior showings on television or in theaters, though the ...

dehisce into the body cavity, floating in its fluids for fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give ...

by male's sperm. After fertilization, each egg contains a developing embryo

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sp ...

. (These embryos hatch into first stage larva

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase ...

.) The fertilized eggs are brought into the uterus

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', : uteri or uteruses) or womb () is the hollow organ, organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans, that accommodates the embryonic development, embryonic and prenatal development, f ...

by actions of the ''uterine bell'', a funnel like opening continuous with the uterus. At the junction of the bell and the uterus there is a second, smaller opening situated dorsally

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position provi ...

. The bell "swallows" the matured eggs and passes them on into the uterus. (Immature embryos are passed back into the body cavity through the dorsal opening.) From the uterus, mature eggs leave the female's body via her oviduct

The oviduct in vertebrates is the passageway from an ovary. In human females, this is more usually known as the fallopian tube. The eggs travel along the oviduct. These eggs will either be fertilized by spermatozoa to become a zygote, or will dege ...

, pass into the host's alimentary canal and are expelled from the host's body within feces

Feces (also known as faeces American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or fæces; : faex) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the ...

.

Release

Having been expelled by the female, the acanthocephalan egg is released along with the feces of the host. For development to occur, the egg, containing the acanthor, needs to be ingested by an

Having been expelled by the female, the acanthocephalan egg is released along with the feces of the host. For development to occur, the egg, containing the acanthor, needs to be ingested by an arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

, usually a crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

(there is one known life cycle which uses a mollusc

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

as a first intermediate host). Inside the intermediate host, the acanthor is released from the egg and develops into an acanthella. It then penetrates the gut wall, moves into the body cavity, encysts, and begins transformation into the infective cystacanth stage. This form has all the organs of the adult save the reproductive ones.

The parasite is released when the first intermediate host is ingested. This can be by a suitable final host, in which case the cystacanth develops into a mature adult, or by a paratenic

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasitic, a mutualistic, or a commensalist ''guest'' (symbiont). The guest is typically provided with nourishment and shelter. Examples include a ...

host, in which the parasite again forms a cyst. When consumed by a suitable final host, the cycstacant ''excysts'', everts its proboscis and pierces the gut wall. It then feeds, grows and develops its sexual organs. Adult worms then mate. The male uses the excretions of its ''cement glands'' to plug the vagina

In mammals and other animals, the vagina (: vaginas or vaginae) is the elastic, muscular sex organ, reproductive organ of the female genital tract. In humans, it extends from the vulval vestibule to the cervix (neck of the uterus). The #Vag ...

of the female, preventing subsequent matings from occurring. Embryos develop inside the female, and the life cycle repeats.

Host control

Thorny-headed worms begin their life cycle inside invertebrates that reside in marine or freshwater systems. One example is ''Polymorphus paradoxus.'' '' Gammarus lacustris'', a small crustacean that inhabits ponds and rivers, is one invertebrate that ''P. paradoxus'' may occupy; ducks are one of the definitive hosts. This crustacean is preyed on by ducks and hides by avoiding light and staying away from the surface. However, infection by ''P. paradoxus'' changes its behavior and appearance in a number of ways that increase its chance of being eaten. First, infection significantly reduces ''G. lacustriss photophobia; as a result, it becomes attracted toward light and swims to the surface. Second, an infected organism will even go so far as to find a rock or a plant on the surface, clamp its mouth down, and latch on, making it easy prey for the duck. Finally, infection reduces the pigment distribution and amount in ''G. lacustris,'' causing the host to turn blue; unlike their normal brown colour, this makes the crustacean stand out and increases the chance the duck will see it. Experiments have shown that altered serotonin levels are likely responsible for at least some of these changes in behaviour. One experiment found that serotonin induces clinging behavior in ''G. lacustris'' similar to that seen in infected organisms. Another showed that infected ''G. lacustris'' had approximately 3 times as manyserotonin

Serotonin (), also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), is a monoamine neurotransmitter with a wide range of functions in both the central nervous system (CNS) and also peripheral tissues. It is involved in mood, cognition, reward, learning, ...

-producing sites in its ventral nerve cord. Furthermore, experiments in closely-related species of ''Polymorphus'' and ''Pomphorhynchus'' infecting other ''Gammarus'' species confirmed this relation: infected organisms were considerably more attracted to light and had higher serotonin levels, while the phototropism could be duplicated by injections of serotonin.

Effects on hosts

'' Polymorphus'' spp. are parasites ofseabirds

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same envi ...

, particularly the eider duck

The eiders () are large Mergini, seaducks in the genus ''Somateria''. The three extant species all breed in the cooler latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

The down feathers of eider ducks and some other ducks and geese are used to fill pillow ...

(''Somateria mollissima''). Heavy infections of up to 750 parasites per bird are common, causing ulceration

An ulcer is a discontinuity or break in a bodily membrane that impedes normal function of the affected Organ (biology), organ. According to Robbins's pathology, "ulcer is the breach of the continuity of skin, epithelium or mucous membrane caus ...

to the gut, disease and seasonal mortality. Recent research has suggested that there is no evidence of pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

icity of ''Polymorphus'' spp. to intermediate crab hosts. The cystacanth stage is long lived and probably remains infectious throughout the life of the crab.

Economic impact

Acanthocephalosis, a disease caused by ''Acanthacephalus'' infection, is prevalent in aquaculture, occurring inAtlantic salmon

The Atlantic salmon (''Salmo salar'') is a species of ray-finned fish in the family Salmonidae. It is the third largest of the Salmonidae, behind Hucho taimen, Siberian taimen and Pacific Chinook salmon, growing up to a meter in length. Atlan ...

, rainbow

A rainbow is an optical phenomenon caused by refraction, internal reflection and dispersion of light in water droplets resulting in a continuous spectrum of light appearing in the sky. The rainbow takes the form of a multicoloured circular ...

and brown trout

The brown trout (''Salmo trutta'') is a species of salmonid ray-finned fish and the most widely distributed species of the genus ''Salmo'', endemic to most of Europe, West Asia and parts of North Africa, and has been widely introduced globally ...

, tilapia

Tilapia ( ) is the common name for nearly a hundred species of cichlid fish from the coelotilapine, coptodonine, heterotilapine, oreochromine, pelmatolapiine, and tilapiine tribes (formerly all were "Tilapiini"), with the economically mos ...

, and tambaqui

The tambaqui (''Colossoma macropomum'') is a large species of freshwater fish in the family Serrasalmidae. It is native to tropical South America, but kept in aquaculture and Introduced species, introduced elsewhere. It is also known by the names ...

. Increasing occurrence in Brazilian farming of tambaqui has been reported, and in 2003 ''Acanthacephalus'' was first reported in cultured red snapper in Taiwan.

The life cycle of ''Polymorphus'' spp. normally occurs between sea ducks (e.g. eider

The eiders () are large seaducks in the genus ''Somateria''. The three extant species all breed in the cooler latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

The down feathers of eider ducks and some other ducks and geese are used to fill pillows and qu ...

s and scoter

The scoters are stocky seaducks in the genus ''Melanitta''. The drakes are mostly black and have swollen bills, the females are brown. They breed in the far north of Europe, Asia, and North America, and bird migration, winter further south in te ...

s) and small crabs. Infections found in commercial-sized lobster

Lobsters are Malacostraca, malacostracans Decapoda, decapod crustaceans of the family (biology), family Nephropidae or its Synonym (taxonomy), synonym Homaridae. They have long bodies with muscular tails and live in crevices or burrows on th ...

s in Canada were probably acquired from crabs that form an important dietary item of lobsters. Cystacanths occurring in lobsters can cause economic loss to fishermen. There are no known methods of prevention or control.

Human infections

Although they rarely infect humans, worms in the phylumAcanthocephala

Acanthocephala ( Greek , ' 'thorn' + , ' 'head') is a group of parasitic worms known as acanthocephalans, thorny-headed worms, or spiny-headed worms, characterized by the presence of an eversible proboscis, armed with spines, which it uses t ...

cause the disease acanthocephaliasis Acanthocephaliasis is a human disease caused by Parasitism, parasitic worms in the phylum Acanthocephala. They rarely infect humans. The worms' typical definitive hosts are racoons, rats, and swine, but it can survive in humans. ''Macracanthorhynchu ...

in humans. The earliest known infection was found in a prehistoric man in Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

. This infection was dated to 1869 ± 160 BC. The species involved was thought to be '' Moniliformis clarki'' which is still common in the area.

The first report of an isolate in historic times was by Lambl in 1859 when he isolated ''Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus

''Macracanthorhynchus'', also known as the giant thorny-headed worm of swine, is a member of the Oligacanthorhynchidae which contains four species. Taxonomy

Phylogenetic analysis has been conducted on at least one of the four species in the gen ...

'' from a child in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

. Lindemann in 1865 reported that this organism was commonly isolated in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. The reason for this was discovered by Schneider in 1871 when he found that an intermediate host, the scarabaeid beetle grub, was commonly eaten raw.

The first report of clinical symptoms was by Calandruccio who in 1888 while in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

infected himself by ingesting larvae. He reported gastrointestinal disturbances and shed eggs in two weeks. Subsequent natural infections have since been reported.

Eight species have been isolated from humans to date. ''Moniliformis moniliformis

''Moniliformis moniliformis'' is a parasite of the Acanthocephala phylum in the family Moniliformidae. The adult worms are usually found in intestines of rodents or carnivores such as cats and dogs. The species can also infest humans, though thi ...

'' is the most common isolate. Other isolates include '' Acanthocephalus bufonis'' and ''Corynosoma strumosum

''Corynosoma'' is a genus of parasitic worms belonging to the family Polymorphidae.

The genus has almost cosmopolitan distribution.

Species:

*'' Corynosoma alaskensis''

*'' Corynosoma australe''

*'' Corynosoma beaglense''

*'' Corynosoma bu ...

''.

See also

*Cestoda

Cestoda is a class of parasitic worms in the flatworm phylum (Platyhelminthes). Most of the species—and the best-known—are those in the subclass Eucestoda; they are ribbon-like worms as adults, commonly known as tapeworms. Their bodies co ...

* Digenea

Digenea (Gr. ''Dis'' – double, ''Genos'' – race) is a class of trematodes in the Platyhelminthes phylum, consisting of parasitic flatworms (known as ''flukes'') with a syncytial tegument and, usually, two suckers, one ventral and one or ...

* Monogenea

Monogeneans, members of the class Monogenea, are a group of ectoparasitic flatworms commonly found on the skin, gills, or fins of fish. They have a direct lifecycle and do not require an intermediate host. Adults are hermaphrodites, meaning they ...

References

Further reading

* * * *External links

{{Authority controlAcanthocephalans

Acanthocephala ( Greek , ' 'thorn' + , ' 'head') is a group of parasitic worms known as acanthocephalans, thorny-headed worms, or spiny-headed worms, characterized by the presence of an eversible proboscis, armed with spines, which it uses t ...

Protostome phyla

Veterinary parasitology

Mind-altering parasites

Suicide-inducing parasitism

Taxa named by Joseph Gottlieb Kölreuter