Acadia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Acadia (; ) was a colony of

Explorer

Explorer

From 1640 to 1645, Acadia was plunged into what some historians have described as a civil war. The war was between Port Royal, where the Governor of Acadia Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay was stationed, and present-day

From 1640 to 1645, Acadia was plunged into what some historians have described as a civil war. The war was between Port Royal, where the Governor of Acadia Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay was stationed, and present-day

During the escalation that preceded

During the escalation that preceded

Among the Acadian descendants in the Canadian Maritime provinces, there was a revival of cultural awareness which is recognized as an Acadian Renaissance, with a struggle for recognition of Acadians as a distinct group starting in the mid-nineteenth century. Some Acadian deputies were elected to legislative assemblies, starting in 1836 with

Among the Acadian descendants in the Canadian Maritime provinces, there was a revival of cultural awareness which is recognized as an Acadian Renaissance, with a struggle for recognition of Acadians as a distinct group starting in the mid-nineteenth century. Some Acadian deputies were elected to legislative assemblies, starting in 1836 with

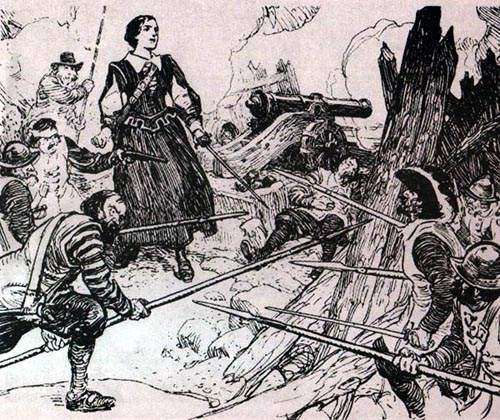

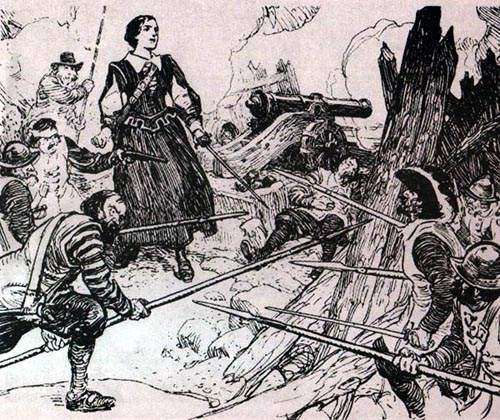

File:Charles d'Aulnay.jpg, Charles de Menou d'Aulnay – Civil War in Acadia

File:Portrait Françoise-Marie Jacquelin.jpg, Françoise-Marie Jacquelin – Civil War in Acadia

File:BaronDeStCastin1881byWill H Lowe Wilson Museum Archives.jpg, Baron de Saint-Castin – Castine's War

File:Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville.jpg, Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville –

A

A

Acadian Heritage Portal

– Acadian history, genealogy and folklore

National Society of Acadia

Acadian Ancestral Home by Lucie LeBlanc Consentino – a repository for Acadian history & genealogy

{{Coord, 46, N, 9=type:city_source:kolossus-dawiki, display=title, 64, W Culture of New Brunswick Culture of Prince Edward Island New Netherland Pre-Confederation New Brunswick Pre-Confederation Nova Scotia Pre-Confederation Prince Edward Island History of New Brunswick History of Nova Scotia History of Prince Edward Island 1604 establishments in New France 1713 disestablishments in New France States and territories established in 1604 States and territories disestablished in 1713

New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

in northeastern North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of ...

, the Gaspé Peninsula

The Gaspé Peninsula, also known as Gaspesia (, ; ), is a peninsula along the south shore of the St. Lawrence River that extends from the Matapedia Valley in Quebec, Canada, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. It is separated from New Brunswick on it ...

and Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

to the Kennebec River

The Kennebec River (Abenaki language, Abenaki: ''Kinəpékʷihtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 30, 2011 natural river within the U.S. state of Ma ...

. The population of Acadia included the various indigenous First Nations

First nations are indigenous settlers or bands.

First Nations, first nations, or first peoples may also refer to:

Indigenous groups

*List of Indigenous peoples

*First Nations in Canada, Indigenous peoples of Canada who are neither Inuit nor Mé ...

that comprised the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner"; also: Wabanakia, "Dawnland") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of five principal Eastern Algonquian nations ...

, the Acadian people and other French settlers.

The first capital of Acadia was established in 1605 as Port-Royal. Soon after, English forces of Captain Argall, an English ship's captain employed by the Virginia Company of London attacked and burned down the fortified habitation in 1613. A new centre for Port-Royal was established nearby, and it remained the longest-serving capital of French Acadia until the British siege of Port Royal in 1710.

There were six colonial wars in a 74-year period in which British interests tried to capture Acadia, starting with King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Allian ...

in 1689. French troops from Quebec, Acadians, the Wabanaki Confederacy, and French priests continually raided New England settlements along the border in Maine during these wars.

Acadia was conquered in 1710 during Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) or the Third Indian War was one in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Gr ...

, while New Brunswick and much of Maine remained contested territory. Prince Edward Island (Île Saint-Jean) and Cape Breton (Île Royale) remained under French control, as agreed under Article XIII of the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaty, peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vac ...

. The English took control of Maine by defeating the Wabanaki Confederacy and the French priests during Father Rale's War. During King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in ...

, France and New France made significant attempts to regain mainland Nova Scotia. The British took New Brunswick in Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Kingdo ...

, and they took Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean in 1758 following the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

. The territory was eventually divided into British colonies.

The term Acadia today refers to regions of North America that are historically associated with the lands, descendants, or culture of the former region. It particularly refers to regions of the Maritimes with Acadian roots, language, and culture, primarily in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, the Magdalen Islands and Prince Edward Island, as well as in Maine. "Acadia" can also refer to the Acadian diaspora in southern Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, a region also referred to as Acadiana

Acadiana (; French language, French and Cajun French language, Louisiana French: ''L'Acadiane'' or ''Acadiane''), also known as Cajun Country (Cajun French language, Louisiana French: ''Pays des Cadiens''), is the official name given to the ...

since the early 1960s. In the abstract, Acadia refers to the existence of an Acadian culture in any of these regions. People living in Acadia are called Acadians

The Acadians (; , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French colonial empire, French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Today, most descendants of Acadians live in either the Northern Americ ...

, which in Louisiana changed to Cajuns

The Cajuns (; Louisiana French language, French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana ''Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French people, Louisiana French ethnic group, ethnicity mainly found in t ...

, the more common, rural American, name of Acadians.

Etymology

Explorer

Explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano

Giovanni da Verrazzano ( , ; often misspelled Verrazano in English; 1491–1528) was an Italian ( Florentine) explorer of North America, who led most of his later expeditions, including the one to America, in the service of King Francis I of ...

is credited for originating the designation Acadia on his 16th-century map, where he applied the ancient Greek name "Arcadia" to the entire Atlantic coast north of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. "Arcadia" is derived from the Arcadia region in Greece, which had the extended meanings of "refuge" or "idyllic place". Henry IV of France

Henry IV (; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry (''le Bon Roi Henri'') or Henry the Great (''Henri le Grand''), was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 16 ...

chartered a colony south of the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (, ) is a large international river in the middle latitudes of North America connecting the Great Lakes to the North Atlantic Ocean. Its waters flow in a northeasterly direction from Lake Ontario to the Gulf of St. Lawren ...

between the 40th and 46th parallels in 1603, and he recognized it as ''La Cadie''. Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; 13 August 1574#Fichier]For a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see #Ritch, RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December ...

fixed its present orthography with the ''r'' omitted, and cartographer William Francis Ganong has shown its gradual progress northeastwards to its resting place in the Atlantic provinces of Canada.

As an alternative theory, some historians suggest that the name is derived from the indigenous Canadian Miꞌkmaq language

The Miꞌkmaq language ( ; ), or , is an Eastern Algonquian language spoken by nearly 11,000 Miꞌkmaq in Canada and the United States; the total ethnic Miꞌkmaq population is roughly 20,000. The native name of the language is , or (in some ...

, in which Cadie means "fertile land".

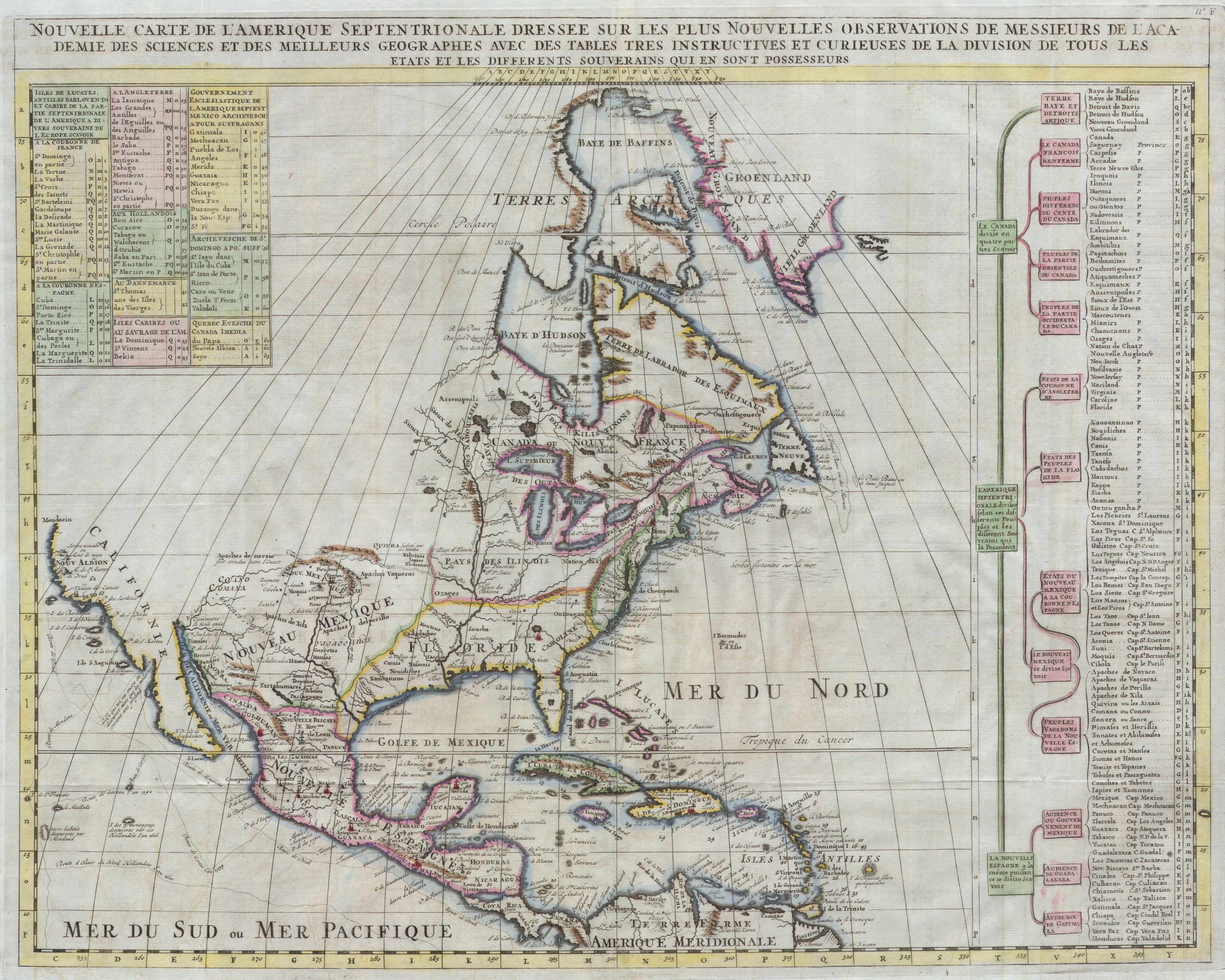

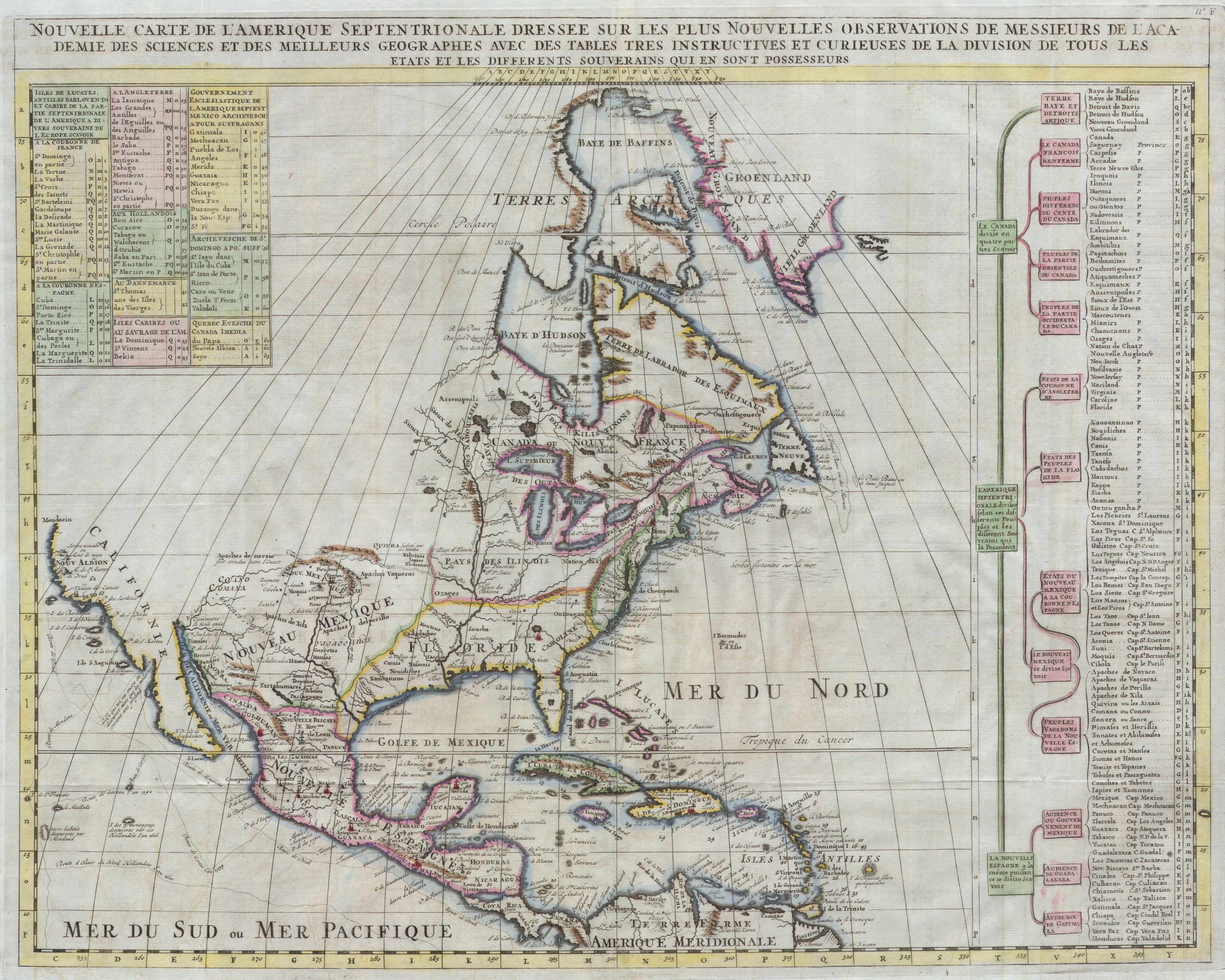

Territory

During much of the 17th and early 18th centuries,Norridgewock

Norridgewock (Abenaki language, Abenaki: ''Nanrantsouak'') was the name of both an Indigenous village and a Band society, band of the Abenaki ("People of the Dawn") Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans/First Nations in Canada, ...

on the Kennebec River

The Kennebec River (Abenaki language, Abenaki: ''Kinəpékʷihtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 30, 2011 natural river within the U.S. state of Ma ...

and Castine at the end of the Penobscot River

The Penobscot River (Abenaki: ''Pαnawάhpskewtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 22, 2011 river in the U.S. state of Maine. Including the river's W ...

were the southernmost settlements of Acadia.

The French government defined the borders of Acadia as roughly between the 40th and 46th parallels on the Atlantic coast.

The borders of French Acadia were not clearly defined, but the following areas were at some time part of French Acadia :

* Present-day mainland Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

, with Port Royal as its capital. Lost to Great Britain in 1713.

* Present-day New Brunswick

New Brunswick is a Provinces and Territories of Canada, province of Canada, bordering Quebec to the north, Nova Scotia to the east, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the northeast, the Bay of Fundy to the southeast, and the U.S. state of Maine to ...

, which remained part of Nova Scotia until becoming a separate colony in 1784. Lost to Great Britain in 1763.

* Île-Royale, later ''Cape Breton Island'', with the Fortress of Louisbourg

The Fortress of Louisbourg () is a tourist attraction as a National Historic Sites of Canada, National Historic Site and the location of a one-quarter partial reconstruction of an 18th-century Kingdom of France, French fortress at Louisbourg, Nov ...

. Lost to Great Britain in 1763.

* Île Saint-Jean, later ''Prince Edward Island''. Lost to Great Britain in 1763.

* The part of present-day Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

east of the Kennebec River

The Kennebec River (Abenaki language, Abenaki: ''Kinəpékʷihtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 30, 2011 natural river within the U.S. state of Ma ...

. Lost to Great Britain in 1763.

History

17th century

The history of Acadia was significantly influenced by the great power conflict between France and England, later Great Britain, that occurred in the 17th and 18th centuries. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Mi'kmaq had been living in Acadia for at least two to three thousand years. Early European settlers were French subjects primarily from the Poitou-Charentes andAquitaine

Aquitaine (, ; ; ; ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne (), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former Regions of France, administrative region. Since 1 January 2016 it has been part of the administ ...

regions of southwestern France, now known as Nouvelle-Aquitaine

Nouvelle-Aquitaine () is the largest Regions of France, administrative region in France by area, spanning the west and southwest of Metropolitan France. The region was created in 2014 by the merging of Aquitaine, Limousin, and Poitou-Charentes ...

. The first French settlement was established by Pierre Dugua de Mons, Governor of Acadia, under the authority of the French King, Henri IV, on Saint Croix Island in 1604. The following year, the settlement was moved across the Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy () is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its tidal range is the highest in the world.

The bay was ...

to Port Royal after a difficult winter on the island and deaths from scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

. There, they constructed a new habitation. In 1607, the colony received bad news as Henri IV revoked Sieur de Mons' royal fur monopoly, citing that the income was insufficient to justify supplying the colony further. Thus recalled, the last of the French left Port Royal in August 1607. Their allies, the Mi'kmaq, agreed to act as custodians of the settlement. When the former lieutenant governor, Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt et de Saint-Just

Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt et de Saint-Just (Jean Biencourt, Baron of Poutrincourt and Saint-Just) (1557–1615) was a member of the French nobility best remembered as a commander of the French colonial empire, one of those responsible for ...

, returned in 1610, he found the Port Royal habitation just as it was left.

During the first 80 years of the French presence in Acadia, there were numerous significant battles as the English, Scottish, and Dutch contested the French for possession of the colony. These battles happened at Port Royal, Saint John, Cap de Sable (present-day Port La Tour, Nova Scotia), Jemseg, Castine, and Baleine.

From the 1680s onward, there were six colonial wars that took place in the region (see the French and Indian Wars

The French and Indian Wars were a series of conflicts that occurred in North America between 1688 and 1763, some of which indirectly were related to the European dynastic wars. The title ''French and Indian War'' in the singular is used in the U ...

as well as Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Kingdo ...

). These wars were fought between New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

and New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

, and their respective native allies. After the British siege of Port Royal in 1710, mainland Nova Scotia was under the control of British colonial government, but both present-day New Brunswick

New Brunswick is a Provinces and Territories of Canada, province of Canada, bordering Quebec to the north, Nova Scotia to the east, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the northeast, the Bay of Fundy to the southeast, and the U.S. state of Maine to ...

and virtually all of present-day Maine remained contested territory between New England and New France, until the Treaty of Paris of 1763 confirmed British control over the region.

The wars were fought on two fronts: the southern border of Acadia, which New France defined as the Kennebec River

The Kennebec River (Abenaki language, Abenaki: ''Kinəpékʷihtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 30, 2011 natural river within the U.S. state of Ma ...

in southern Maine and in present-day peninsular Nova Scotia. The latter involved preventing the British from taking the capital of Acadia, Port Royal (See Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) or the Third Indian War was one in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Gr ...

), establishing themselves at Canso (See Father Rale's War) and founding Halifax (see Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Kingdo ...

).

Acadian Civil War

From 1640 to 1645, Acadia was plunged into what some historians have described as a civil war. The war was between Port Royal, where the Governor of Acadia Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay was stationed, and present-day

From 1640 to 1645, Acadia was plunged into what some historians have described as a civil war. The war was between Port Royal, where the Governor of Acadia Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay was stationed, and present-day Saint John, New Brunswick

Saint John () is a port#seaport, seaport city located on the Bay of Fundy in the province of New Brunswick, Canada. It is Canada's oldest Municipal corporation, incorporated city, established by royal charter on May 18, 1785, during the reign ...

, where Governor of Acadia Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour

Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour (1593–1666) was a Huguenot French colonist and fur trader who served as Governor of Acadia from 1631–1642 and again from 1653–1657.

Early life

Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour was born in France i ...

was stationed. There were four major battles in the war, and d'Aulnay ultimately prevailed over La Tour.

King Philip's War

DuringKing Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1678 between a group of indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodland ...

(1675–78), the governor was absent from Acadia (having first been imprisoned in Boston during the Dutch occupation of Acadia) and Jean-Vincent d'Abbadie de Saint-Castin was established at the capital of Acadia, Pentagouêt. From there he worked with the Abenaki of Acadia to raid British settlements migrating over the border of Acadia. British retaliation included attacking deep into Acadia in the Battle off Port La Tour (1677).

Wabanaki Confederacy

In response toKing Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1678 between a group of indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodland ...

in New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

, the native peoples in Acadia joined the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner"; also: Wabanakia, "Dawnland") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of five principal Eastern Algonquian nations ...

to form a political and military alliance with New France. The Confederacy remained significant military allies to New France through six wars. Until the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

the Wabanaki Confederacy remained the dominant military force in the region.

Catholic missions

There were tensions on the border between New England and Acadia, which New France defined as theKennebec River

The Kennebec River (Abenaki language, Abenaki: ''Kinəpékʷihtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 30, 2011 natural river within the U.S. state of Ma ...

in southern Maine. English settlers from Massachusetts (whose charter included the Maine area) had expanded their settlements into Acadia. To secure New France's claim to Acadia, it established Catholic missions (churches) among the four largest native villages in the region: one on the Kennebec River (Norridgewock

Norridgewock (Abenaki language, Abenaki: ''Nanrantsouak'') was the name of both an Indigenous village and a Band society, band of the Abenaki ("People of the Dawn") Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans/First Nations in Canada, ...

); one further north on the Penobscot River

The Penobscot River (Abenaki: ''Pαnawάhpskewtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 22, 2011 river in the U.S. state of Maine. Including the river's W ...

(Penobscot

The Penobscot (Abenaki: ''Pαnawάhpskewi'') are an Indigenous people in North America from the Northeastern Woodlands region. They are organized as a federally recognized tribe in Maine and as a First Nations band government in the Atlantic p ...

); one on the Saint John River ( Medoctec); and one at Shubenacadie (Saint Anne's Mission).

King William's War

DuringKing William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Allian ...

(1688–97), some Acadians, the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner"; also: Wabanakia, "Dawnland") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of five principal Eastern Algonquian nations ...

and the French Priests participated in defending Acadia at its border with New England, which New France defined as the Kennebec River

The Kennebec River (Abenaki language, Abenaki: ''Kinəpékʷihtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 30, 2011 natural river within the U.S. state of Ma ...

in southern Maine. Toward this end, the members of the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner"; also: Wabanakia, "Dawnland") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of five principal Eastern Algonquian nations ...

, on the Saint John River and in other places, joined the New France expedition against present-day Bristol, Maine (the siege of Pemaquid (1689)), Salmon Falls and present-day Portland, Maine

Portland is the List of municipalities in Maine, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine and the county seat, seat of Cumberland County, Maine, Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 at the 2020 census. The Portland metropolit ...

.

In response, the New Englanders retaliated by attacking Port Royal and present-day Guysborough. In 1694, the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner"; also: Wabanakia, "Dawnland") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of five principal Eastern Algonquian nations ...

participated in the Raid on Oyster River at present-day Durham, New Hampshire

Durham is a New England town, town in Strafford County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 15,490 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, up from 14,638 at the 2010 census.United States Census BureauU.S. Census website 2010 ...

. Two years later, New France, led by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

, returned and fought a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy before moving on to raid Bristol, Maine, again.

In retaliation, the New Englanders, led by Benjamin Church, engaged in a Raid on Chignecto (1696) and the siege of the Capital of Acadia at Fort Nashwaak.

At the end of the war England returned the territory to France in the Treaty of Ryswick and the borders of Acadia remained the same.

18th century

Queen Anne's War

DuringQueen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) or the Third Indian War was one in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Gr ...

, some Acadians, the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner"; also: Wabanakia, "Dawnland") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of five principal Eastern Algonquian nations ...

and the French priests participated again in defending Acadia at its border with New England. They made numerous raids on New England settlements along the border in the Northeast Coast Campaign and the famous Raid on Deerfield. In retaliation, Major Benjamin Church went on his fifth and final expedition to Acadia. He raided present-day Castine, Maine and continued with raids against Grand Pre, Pisiquid, and Chignecto. A few years later, defeated in the siege of Pemaquid (1696)

The siege of Pemaquid occurred during King William's War when French and Native forces from New France attacked the English overseas possessions, English settlement at Pemaquid (present-day Bristol, Maine), a community on the border with Acadia. ...

, Captain March made an unsuccessful siege on the Capital of Acadia, Port Royal (1707). British forces were successful with the siege of Port Royal (1710)

The siege of Port Royal (5–13 October 1710),Dates in this article are given in the New Style; many older English accounts use Old Style dates for this action: 24 September to 2 October also known as the Conquest of Acadia, was a military sie ...

, while the Wabanaki Confederacy were successful in the nearby Battle of Bloody Creek (1711) and continued raids along the Maine frontier.

The 1710 conquest of the Acadian capital of Port Royal during the war was confirmed by the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaty, peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vac ...

of 1713. The British conceded to the French "the island called Cape Breton

Cape Breton Island (, formerly '; or '; ) is a rugged and irregularly shaped island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18.7% of Nova Scotia's total area. Although ...

, as also all others, both in the mouth of the river of St. Lawrence, and in the gulph of the same name", and "all manner of liberty to fortify any place or places there." The French established a fortress at Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The harbour had been used by European mariners since at least the 1590s, when it was known as English Port and Havre à l'An ...

, Cape Breton, to guard the sea approaches to Quebec.

On 23 June 1713, the French residents of Nova Scotia were given one year to declare allegiance to Britain or leave the region. In the meantime, the French signalled their preparedness for future hostilities by beginning the construction of Fortress Louisbourg on Île Royale, now Cape Breton Island. The British grew increasingly alarmed by the prospect of disloyalty in wartime of the Acadians now under their rule. French missionaries worked to maintain the loyalty of Acadians, and to maintain a hold on the mainland part of Acadia.

Dummer's War

During the escalation that preceded

During the escalation that preceded Dummer's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) (also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War) was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the Wab ...

(1722–1725), some Acadians, the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner"; also: Wabanakia, "Dawnland") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of five principal Eastern Algonquian nations ...

and the French priests persisted in defending Acadia, which had been conceded to the British in the Treaty of Utrecht, at its border against New England. The Miꞌkmaq refused to recognize the treaty handing over their land to the English and hostilities resumed. The Miꞌkmaq raided the new fort at Canso, Nova Scotia in 1720. The Confederacy made numerous raids on New England settlements along the border into New England. Towards the end of January 1722, Governor Samuel Shute

Samuel Shute (January 12, 1662 – April 15, 1742) was an English military officer and royal governor of the provinces of Massachusetts and New Hampshire. After serving in the Nine Years' War and the War of the Spanish Succession, he was appo ...

chose to launch a punitive expedition against Sébastien Rale

Sébastien Rale (; also Racle, Râle, Rasle, Rasles, and Sebastian Rale; January 20, 1657 – August 23, 1724) was a French Society of Jesus, Jesuit missionary and lexicographer who preached amongst the Abenaki and encouraged their resistanc ...

, a Jesuit missionary, at Norridgewock

Norridgewock (Abenaki language, Abenaki: ''Nanrantsouak'') was the name of both an Indigenous village and a Band society, band of the Abenaki ("People of the Dawn") Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans/First Nations in Canada, ...

. This breach of the border of Acadia, which had at any rate been ceded to the British, drew all of the tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy into the conflict.

Under potential siege by the Confederacy, in May 1722, Lieutenant Governor John Doucett took 22 Miꞌkmaq hostage at Annapolis Royal to prevent the capital from being attacked. In July 1722, the Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pred ...

and Miꞌkmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Mi'kmaw'' or ''Mi'gmaw''; ; , and formerly Micmac) are an Indigenous group of people of the Northeastern Woodlands, native to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces, primarily Nova Scotia, New Bru ...

created a blockade of Annapolis Royal, with the intent of starving the capital. The natives captured 18 fishing vessels and prisoners from present-day Yarmouth to Canso. They also seized prisoners and vessels from the Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy () is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its tidal range is the highest in the world.

The bay was ...

.

As a result of the escalating conflict, Massachusetts Governor Shute officially declared war on 22 July 1722. The first battle of Father Rale's War happened in the Nova Scotia theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a Stage (theatre), stage. The performe ...

. In response to the blockade of Annapolis Royal, at the end of July 1722, New England launched a campaign to end the blockade and retrieve over 86 New England prisoners taken by the natives. One of these operations resulted in the Battle at Jeddore. The next was a raid on Canso in 1723. Then in July 1724 a group of sixty Miꞌkmaq and Wolastoqiyik raided Annapolis Royal.

As a result of Father Rale's War, present-day central Maine fell again to the British with the defeat of Sébastien Rale at Norridgewock and the subsequent retreat of the native population from the Kennebec and Penobscot rivers.

King George's War

King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in ...

began when the war declarations from Europe reached the French fortress at Louisbourg first, on May 3, 1744, and the forces there wasted little time in beginning hostilities. Concerned about their overland supply lines to Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

, they first raided the British fishing port of Canso on May 23, and then organized an attack on Annapolis Royal, then the capital of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

. However, French forces were delayed in departing Louisbourg, and their Miꞌkmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Mi'kmaw'' or ''Mi'gmaw''; ; , and formerly Micmac) are an Indigenous group of people of the Northeastern Woodlands, native to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces, primarily Nova Scotia, New Bru ...

and Wolastoqey allies decided to attack on their own in early July. Annapolis had received news of the war declaration, and was somewhat prepared when the Indians began besieging Fort Anne. Lacking heavy weapons, the Indians withdrew after a few days. Then, in mid-August, a larger French force arrived before Fort Anne, but was also unable to mount an effective attack or siege against the garrison, which had received supplies and reinforcements from Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

. In 1745, British colonial forces conducted the siege of Port Toulouse (St. Peter's) and then captured Fortress Louisbourg after a siege of six weeks. France launched a major expedition to recover Acadia in 1746. Beset by storms, disease, and finally the death of its commander, the Duc d'Anville, it returned to France in tatters without reaching its objective. French officer Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Roch de Ramezay also arrived from Quebec and conducted the Battle at Port-la-Joye on Île Saint-Jean and the Battle of Grand Pré.

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755)

Despite the British capture of the Acadian capital in thesiege of Port Royal (1710)

The siege of Port Royal (5–13 October 1710),Dates in this article are given in the New Style; many older English accounts use Old Style dates for this action: 24 September to 2 October also known as the Conquest of Acadia, was a military sie ...

, Nova Scotia remained primarily occupied by Catholic Acadians and Miꞌkmaq. To prevent the establishment of Protestant settlements in the region, Miꞌkmaq raided the early British settlements of present-day Shelburne (1715) and Canso (1720). A generation later, Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Kingdo ...

began when Edward Cornwallis arrived to establish Halifax with 13 transports on 21 June 1749. The British quickly began to build other settlements. To guard against Miꞌkmaq, Acadian and French attacks on the new Protestant settlements, they erected fortifications in Halifax (Citadel Hill) (1749), Dartmouth (1750), Bedford (Fort Sackville) (1751), Lunenburg (1753) and Lawrencetown (1754). There were numerous Miꞌkmaq and Acadian raids on these villages such as the Raid on Dartmouth (1751).

Within 18 months of establishing Halifax, the British also took firm control of peninsular Nova Scotia by building fortifications in all the major Acadian communities: present-day Windsor ( Fort Edward, 1750); Grand Pre ( Fort Vieux Logis, 1749) and Chignecto ( Fort Lawrence, 1750). (A British fort already existed at the other major Acadian centre of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia

Annapolis Royal is a town in and the county seat of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada. The community, known as Port Royal before 1710, is recognised as having one of the longest histories in North America, preceding the settlements at Ply ...

. Cobequid remained without a fort.) Numerous Miꞌkmaq and Acadian raids took place against these fortifications, such as the siege of Grand Pre (1749).

Deportation of the Acadians

In the years after the British conquest, the Acadians refused to swear unconditional oaths of allegiance to the British crown. During this time period some Acadians participated in militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to Fortress Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour. During theFrench and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

, the British sought to neutralize any military threat Acadians posed and to interrupt the vital supply lines Acadians provided to Louisbourg by deporting them.

This process began in 1755, after the British captured Fort Beauséjour and began the expulsion of the Acadians

The Expulsion of the Acadians was the forced removal of inhabitants of the North American region historically known as Acadia between 1755 and 1764 by Great Britain. It included the modern Canadian Maritime provinces of Nova Scotia, New Br ...

with the Bay of Fundy Campaign. Between six and seven thousand Acadians were expelled from Nova Scotia to the lower British American colonies. Some Acadians eluded capture by fleeing deep into the wilderness or into French-controlled Canada. The Quebec town of L'Acadie (now a sector of Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu

Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu () is a city in eastern Montérégie in the Canadian province of Quebec, about southeast of Montreal, located roughly halfway between Montreal and the Canada–United States border with the state of Vermont. It is sit ...

) was founded by expelled Acadians. After the siege of Louisbourg (1758)

The siege of Louisbourg was a pivotal operation of the French and Indian War in 1758 that ended French colonial dominance in Atlantic Canada and led to the subsequent British campaign to capture Quebec in 1759 and the remainder of New France ...

, a second wave of the expulsion began with the St. John River Campaign, Petitcodiac River Campaign, Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign and the Île Saint-Jean Campaign.

The Acadians and the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner"; also: Wabanakia, "Dawnland") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of five principal Eastern Algonquian nations ...

created a significant resistance to the British throughout the war. They repeatedly raided Canso, Lunenburg, Halifax, Chignecto and into New England.

Any pretense that France might maintain or regain control over the remnants of Acadia came to an end with the fall of Montreal in 1760 and the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which permanently ceded almost all of eastern New France to Britain. In 1763, Britain would designate lands west of the Appalachians as the "Indian Reserve", but did not respect Miꞌkmaq title to the Atlantic region, claiming title was obtained from the French. The Miꞌkmaq remain in Acadia to this day. After 1764, many exiled Acadians finally settled in Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, which had been transferred by France to Spain as part of the Treaty of Paris which formally ended conflict between France and Great Britain over control of North America (the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

, known as the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

in the United States),. The demonym

A demonym (; ) or 'gentilic' () is a word that identifies a group of people ( inhabitants, residents, natives) in relation to a particular place. Demonyms are usually derived from the name of the place ( hamlet, village, town, city, region, ...

''Acadian'' developed into ''Cajun

The Cajuns (; French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana ''Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French ethnicity mainly found in the US state of Louisiana and surrounding Gulf Coast states.

Whi ...

,'' which was first used as a pejorative term until its later mainstream acceptance.

Britain eventually moderated its policies and allowed Acadians to return to Nova Scotia. However, most of the fertile former Acadian lands were now occupied by British colonists. The returning Acadians settled instead in more outlying areas of the original Acadia, such as Cape Breton and the areas which are now New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.

19th century

Acadian Renaissance

Simon d'Entremont

Simon d'Entremont (October 28, 1788 – September 6, 1886) was a farmer and political figure in Nova Scotia of Acadian descent. He represented Argyle township in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly from 1836 to 1840. D'Entremont and Frederick ...

in Nova Scotia. Several other provincial and federal members followed in New Brunswick and in Prince Edward Island.

This period saw the founding of Acadian higher educational institutions: the Saint Thomas Seminary from 1854 to 1862 and then Saint Joseph's College from 1864, both in Memramcook, New Brunswick. This was followed by the founding of Acadian newspapers: the weekly in 1867 and the daily in 1887 ( fr), named after the epic poem

In poetry, an epic is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants. With regard to ...

by Longfellow.

In New Brunswick the 1870s saw a struggle against the Common Schools Act of 1871, which imposed a non-denominational school system and forbade religious instruction during school hours. This led to widespread Acadian protests and school-tax boycotts, culminating in the 1875 riots in the town of Caraquet. Finally in 1875 a compromise

To compromise is to make a deal between different parties where each party gives up part of their demand. In arguments, compromise means finding agreement through communication, through a mutual acceptance of terms—often involving variations fr ...

was reached allowing for some Catholic religious teaching in the schools.

In the 1880s there began a series of Acadian national conventions. The first in 1881 adopted Assumption Day (Aug.15) as the Acadian national holiday. The convention favored the argument of the priest Marcel-François Richard ( fr) that Acadians are a distinct people which should have a national holiday distinct from that of Quebec (Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day

Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day (), also known in English as ''St John the Baptist Day'', is a holiday celebrated on June 24 in the Canadian province of Quebec. It was brought to Canada by French settlers celebrating the traditional feast day of the Na ...

). The second convention in 1884 adopted other national symbols including the flag of Acadia

The flag of Acadia is a 2:3 ratioed symbolic flag representing the Acadia (region), Acadian community of Canada. It was adopted on 15 August 1884, at the Second Acadian National Convention held in Miscouche, Prince Edward Island, by nearly 5, ...

designed by Marcel-François Richard, and the anthem Ave maris stella. The third convention in 1890 created the Société nationale L'Assomption to promote the interests of the Acadian people in the Maritimes. Other Acadian national conventions continued until the fifteenth in 1972.

In 1885, the author, historian and linguist Pascal Poirier became the first Acadian member of the Senate of Canada

The Senate of Canada () is the upper house of the Parliament of Canada. Together with the Monarchy of Canada#Parliament (King-in-Parliament), Crown and the House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons, they compose the Bicameralism, bicameral le ...

.

20th century and beyond

By the early twentieth century, some Acadians were chosen for leadership positions in New Brunswick. In 1912, Monseigneur Édouard LeBlanc of Nova Scotia was named bishop of Saint John, after a campaign lasting many years to convince the Vatican to appoint an Acadian bishop. In 1917, the premier of Prince Edward Island resigned to accept a judicial position, and his Conservative Party chose Aubin-Edmond Arsenault as successor until the next election in 1919. Arsenault thus became the first Acadian provincial premier of any province in Canada. In 1923, Peter Veniot became the first Acadian premier of New Brunswick when he was chosen by the Liberal Party to complete the term of the retiring premier until 1925. The expansion of Acadian influence in the Catholic church continued in 1936 with the creation of the Archdiocese of Moncton whose first archbishop was Louis-Joseph-Arthur Melanson, and whose Cathédrale Notre-Dame de l’Assomption was completed in 1940. The new archdiocese was expanded to include new predominantly Acadian dioceses inBathurst, New Brunswick

Bathurst () is a city in northern New Brunswick with a population of 12,157 and the 4th largest metropolitan area in New Brunswick as defined by Census Canada with a population of 31,387 as of 2021. The City of Bathurst overlooks Nepisiguit Ba ...

(1938), in Edmundston

Edmundston () is a city in Madawaska County, New Brunswick, Canada. Established in 1850, it had a population of 16,437 as of 2021.

On January 1, 2023, Edmundston amalgamated with the village of Rivière-Verte, New Brunswick, Rivière-Verte and ...

(1944) and in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia

Yarmouth is a port town located on the Bay of Fundy in southwestern Nova Scotia, Canada. Yarmouth is the shire town of Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia, Yarmouth County and is the largest population centre in the region.

History

Originally inhab ...

(1953).

Government of Louis Robichaud

In 1960, Louis Robichaud became the first Acadian to be elected premier of a Canadian province. He was elected premier of New Brunswick in 1960 and served three terms until 1970. The Robichaud government created theUniversité de Moncton

The Université de Moncton is a Canadian French-language university in New Brunswick. It includes campuses in Edmundston, Moncton, and Shippagan.

The university was founded in 1963 following the recommendations of the royal commission on hig ...

in 1963 as a unilingual French-language university, corresponding to the much older unilingual English-language University of New Brunswick

The University of New Brunswick (UNB) is a public university with two primary campuses in Fredericton and Saint John, New Brunswick. It is the oldest English language, English-language university in Canada, and among the oldest public universiti ...

. In 1964, two different deputy ministers of education were named to direct English-language and French-language school systems respectively. In the next few years, the Université de Moncton absorbed the former Saint-Joseph's College, as well as the École Normale (teacher's college) which trained French-speaking teachers for the Acadian schools. In 1977, two French-speaking colleges in Northern New Brunswick were transformed into the Edmundston

Edmundston () is a city in Madawaska County, New Brunswick, Canada. Established in 1850, it had a population of 16,437 as of 2021.

On January 1, 2023, Edmundston amalgamated with the village of Rivière-Verte, New Brunswick, Rivière-Verte and ...

and Shippagan campuses of the Université de Moncton.

The New Brunswick Equal Opportunity program of 1967 introduced reforms of municipal structures, of health care, of education, and of the administration of justice. In general, these changes tended to reduce economic inequality between regions of the province, and therefore tended to favour the disadvantaged Acadian regions.

The New Brunswick Official Languages Act (1969) declared New Brunswick officially bilingual with English and French having equal status as official languages. Residents have the right to receive provincial government services in the official language of their choice.

After 1970

The New Brunswick government of Richard Hatfield (1970–87) cooperated with theGovernment of Canada

The Government of Canada (), formally His Majesty's Government (), is the body responsible for the federation, federal administration of Canada. The term ''Government of Canada'' refers specifically to the executive, which includes Minister of t ...

in including the right to linguistic equality in the province as a part of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The ''Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms'' (), often simply referred to as the ''Charter'' in Canada, is a bill of rights entrenched in the Constitution of Canada, forming the first part of the '' Constitution Act, 1982''. The ''Char ...

of 1982, so that it cannot be rescinded by any future provincial government.

Nova Scotia adopted Bill 65 in 1981 to give Acadian schools legal status, and also created a study program including Acadian history and culture. The Acadian schools were placed under separate management in 1996.

Prince Edward Island provided French-language schools in 1980 in areas with a sufficient number of Acadian students, followed by a French-language school commission for the province in 1990. In 2000 a decision of the Supreme Court of Canada

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC; , ) is the highest court in the judicial system of Canada. It comprises nine justices, whose decisions are the ultimate application of Canadian law, and grants permission to between 40 and 75 litigants eac ...

obliged the provincial government to build French schools at least in Charlottetown

Charlottetown is the capital and largest city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Prince Edward Island, and the county seat of Queens County, Prince Edward Island, Queens County. Named after Queen Charlotte, Charlott ...

and Summerside, the two largest communities.

The new French-language daily newspaper L'Acadie Nouvelle published in Caraquet appeared in 1984, replacing L’Évangeline which ceased publication in 1982.

The series of Acadian National Conventions from 1881 to 1972 was followed by an Acadian National Orientation Convention in 1979 at Edmundston

Edmundston () is a city in Madawaska County, New Brunswick, Canada. Established in 1850, it had a population of 16,437 as of 2021.

On January 1, 2023, Edmundston amalgamated with the village of Rivière-Verte, New Brunswick, Rivière-Verte and ...

. Since 1994, there has been a new series of Acadian World Congress

The Acadian World Congress, or Le Congrès Mondial Acadien, is a festival of Acadian and Cajun culture and history, held every five years. It is also informally known as the ''Acadian Reunion''. Its creator was André Boudreau (1945-2005).

Histor ...

es at five-year intervals starting with 1994 in southeastern New Brunswick and 1999 in Louisiana. The most recent was centered in Summerside, Prince Edward Island

Summerside is a Canadian city in Prince County, Prince Edward Island, Prince County, Prince Edward Island. It is the second largest city in the province and the primary service centre for the western part of the island.

History

Summerside was ...

in 2019.

Notable military figures of Acadia

The following list includes those who were born in Acadia (yet not necessarily of Acadian ethnicity) or those who becamenaturalized

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the ...

citizens prior to the fall of the French in the region in 1763. Those who came for brief periods from other countries are not included (e.g. John Gorham, Edward Cornwallis, James Wolfe

Major-general James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the French at the Battle of the Plains of ...

, Boishébert, etc.).

17th–18th century

Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) or the Third Indian War was one in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Gr ...

File:Daniel d'Auger de Subercase.jpg, Daniel d'Auger de Subercase, last governor of Acadia 1706–1710

File:Old Point Monument, Madison, ME.jpg, Sébastien Rale

Sébastien Rale (; also Racle, Râle, Rasle, Rasles, and Sebastian Rale; January 20, 1657 – August 23, 1724) was a French Society of Jesus, Jesuit missionary and lexicographer who preached amongst the Abenaki and encouraged their resistanc ...

– Father Rale's War

File:Jean-BaptisteCopeSignatureJPEG.jpg, Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope – Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Kingdo ...

File:Abbe Le Loutre.jpg, Jean-Louis Le Loutre – Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Kingdo ...

File:Thomaspichon.jpg, Thomas Pichon

Thomas Pichon (30 March 1700 – 22 November 1781), also known as Thomas Tyrell, was a French government agent during Father Le Loutre's War. Pichon is renowned for betraying the French, Acadian and Mi’kmaq forces by providing information to t ...

File:Joseph Broussard en Acadia HRoe 2009.jpg, Joseph (Beausoleil) Broussard

File:JosephGodin.jpg, Joseph Godin – French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

Others

*Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour

Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour (1593–1666) was a Huguenot French colonist and fur trader who served as Governor of Acadia from 1631–1642 and again from 1653–1657.

Early life

Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour was born in France i ...

– Civil War in Acadia

* Chief Madockawando – King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Allian ...

* John Gyles

John Gyles (1680 at Pemaquid, Maine1755 at Roxbury, Boston) was an interpreter and soldier, most known for captivity narrative, his account of his experiences with the Maliseet tribes at their headquarters at Meductic Indian Village / Fort Medu ...

– King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Allian ...

* Father Louis-Pierre Thury

Louis-Pierre Thury (; c. 1644, Notre Dame de Le Breuil-en-Auge, Breuil en Auge (Department of Calvados), France-June 3, 1699, City of Halifax, Halifax, Nova Scotia) was a French missionary (secular priest) who was sent to North America during the ...

– King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Allian ...

* Pierre Maisonnat dit Baptiste – Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) or the Third Indian War was one in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Gr ...

* Charles Morris (jurist) – King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in ...

* Pierre Maillard – Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Kingdo ...

* Joseph-Nicolas Gautier – Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Kingdo ...

* Pierre II Surette – French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

Government

Acadia was in territory disputed between France and Great Britain. England controlled the area from 1621 to 1632 (seeWilliam Alexander, 1st Earl of Stirling

William Alexander, 1st Earl of Stirling PC (c. 156712 February 1640) was a Scottish courtier and poet who was involved in the Scottish colonisation of Charles Fort, later Port-Royal, Nova Scotia in 1629 and Long Island, New York. His litera ...

) and again from 1654 until 1670 (see William Crowne and Thomas Temple), with control permanently regained by its successor state, the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

, in 1710 (ceded under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713). Although France controlled the territory in the remaining periods, French monarchs consistently neglected Acadia. Civil government under the French regime was held by a series of Governors (see List of governors of Acadia). The government of New France was in Quebec, but it had only nominal authority over the Acadians.

The Acadians implemented village self-rule. Even after Canada had given up its elected spokesmen, the Acadians continued to demand a say in their own government, as late as 1706 petitioning the monarchy to allow them to elect spokesmen each year by a plurality of voices. In a sign of his indifference to the colony, Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

agreed to their demand. This representative assembly was a direct offshoot of a government system that developed out of the seigneurial and church parish imported from Europe. The seigneurial system was a "set of legal regimes and practices pertaining to local landholding, politics, economics, and jurisprudence."

Many of the French governors of Acadia prior to Hector d'Andigné de Grandfontaine held seigneuries in Acadia. As Seigneur, in addition to the power held as governor, they held the right to grant land, collect their seigneurial rents, and act in judgement over disputes within their domain.

After Acadia came under direct Royal rule under Grandfontaine the Seigneurs continued to fulfill governance roles.

The Acadian seignuerial system came to an end when the British Crown bought the seigneurial rights in the 1730s.

The Catholic parish system along with the accompanying parish priest also aided in the development Acadian self-government. Priests, given their respected position, often assisted the community in representation with the civil government at Port Royal/Annapolis Royal. Within each parish the Acadians used the elected (wardens) of the '' conseil de fabrique'' to administer more than just the churches' affairs in the parishes. The Acadians extended this system to see to the administrative needs of the community in general. The Acadians protected this structure from the priests and were "No mere subordinates to clerical authority, wardens were 'always suspicious of any interference by the priests' in the life of the rural parish, an institution which was, ... , largely a creation of the inhabitants." During the British regime many of the deputies were drawn from this group.

The Acadians occupied a borderland region of the British and French empires. As such the Acadian homeland was subjected to the ravages of war on numerous occasions. Through experience the Acadians learned to distrust imperial authorities (British and French). This is evidenced in a small way when Acadians were uncooperative with census takers. Administrators complained of constant in-fighting among the population, which filed many petty civil suits with colonial magistrates. Most of these were over boundary lines, as the Acadians were very quick to protect their new lands.

Governance under the British after 1710

After 1710, the British military administration continued to utilize the deputy system the Acadians had developed under French colonial rule. Prior to 1732 the deputies were appointed by the governor from men in the districts of Acadian families "as ancientest and most considerable in Lands & possessions,". This appears to be in contravention of various British penal laws which made it nearly impossible for Roman Catholics and Protestant recusants to hold military and government positions. The need for effective administration and communication in many of the British colonies trumped the laws. In 1732, the governance institution was formalized. Under the formalized system the colony was divided into eight districts. Annually on October 11 free elections were to take place where each district, depending on its size, was to elect two, three, or four deputies. In observance of the Lord's Day, if October 11 fell on a Sunday the elections were to take place on the immediately following Monday. Notice of the annual election was to be given in all districts thirty days before the election date. Immediately following election, deputies, both outgoing and incoming, were to report to Annapolis Royal to receive the governor's approval and instructions. Prior to 1732 deputies had complained about the time and expense of holding office and carrying out their duties. Under the new elected deputy system each district was to provide for the expenses of their elected deputies. The duties of the deputies were broad and included reporting to the government in council the affairs of the districts, distribution of government proclamations, assistance in the settlement of various local disputes (primarily related to land), and ensuring that various weights and measures used in trade were "Conformable to the Standard". In addition to deputies, several other public positions existed. Each district had a clerk who worked closely with the deputies and under his duties recorded the records and orders of government, deeds and conveyances, and kept other public records. With the rapid expansion of the Acadian populace, there was also a growing number of cattle and sheep. The burgeoning herds and flocks, often free-ranging, necessitated the creation of the position of Overseer of Flocks. These individuals controlled where the flocks grazed, settled disputes and recorded the names of individuals slaughtering animals to ensure proper ownership. Skins and hides were inspected for brands. After the purchase by the British Crown of the seigniorial rights in Acadia, various rents and fees were due to the Crown. In the Minas, Piziquid and Cobequid Districts the seigniorial fees were collected by the "Collector & Receiver of All His Majesty's Quit Rents, Dues, or Revenues". The Collector was to keep a record of all rents and other fees collected, submit the rents to Annapolis Royal, and retain fifteen percent to cover his expenses.Population

Before 1654, trading companies and patent holders concerned with fishing recruited men in France to come to Acadia to work at the commercial outposts. The original Acadian population was a small number ofindentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of Work (human activity), labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as paymen ...

s and soldiers brought by the fur-trading companies.

Gradually, fishermen began settling in the area as well, rather than return to France with the seasonal fishing fleet. The majority of the recruiting took place at La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle'') is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime Departments of France, department. Wi ...

. Between 1653 and 1654, 104 men were recruited at La Rochelle. Of these, 31% were builders, 15% were soldiers and sailors, 8% were food preparers, 6.7% were farm workers, and an additional 6.7% worked in the clothing trades. Fifty-five percent of Acadia's first families came from western and southwestern France, primarily from Poitou

Poitou ( , , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical ...

, Aquitaine

Aquitaine (, ; ; ; ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne (), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former Regions of France, administrative region. Since 1 January 2016 it has been part of the administ ...

, Angoumois, and Saintonge. Over 85% of these (47% of the total), were former residents of the La Chaussée area of Poitou.

Many of the families who arrived in 1632 with Isaac de Razilly

Isaac de Razilly (1587–1635) was a member of the French nobility appointed a knight of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem at the age of 18. He was born at the Château d'Oiseaumelle in the Province of Touraine, France. A member of the French n ...

shared some blood ties; those not related by blood shared cultural ties with the others. The number of original immigrants was very small, and only about 100 surnames existed within the Acadian community.

Many of the earliest French settlers in Acadia intermarried with the local Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Mi'kmaw'' or ''Mi'gmaw''; ; , and formerly Micmac) are an Indigenous group of people of the Northeastern Woodlands, native to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces, primarily Nova Scotia, New Bru ...

tribe.

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

ian lawyer, Marc Lescarbot, who spent just over a year in Acadia, arriving in May 1606, described the Micmac as having "courage, fidelity, generosity, and humanity, and their hospitality is so innate and praiseworthy that they receive among them every man who is not an enemy. They are not simpletons. ... So that if we commonly call them Savages, the word is abusive and unmerited."

Most of the immigrants to Acadia were poor peasants in France, making them social equals in this new context. The colony had very limited economic support or cultural contacts with France, leaving a "social vacuum" that allowed "individual talents and industry ... o supplantinherited social position as the measure of a man's worth." Acadians lived as social equals, with the elderly and priests considered slightly superior.

Unlike the French colonists in Canada and the early English colonies in Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

and Jamestown, Acadians maintained an extended kinship system, and the large extended families assisted in building homes and barns, as well as cultivating and harvesting crops. They also relied on interfamily cooperation to accomplish community goals, such as building dikes to reclaim tidal marshes.

Marriages were generally not love matches but were arranged for economic or social reasons. Parental consent was required for anyone under 25 who wished to marry, and both the mother's and father's consent was recorded in the marriage deed. Divorce was not permitted in New France, and annulments were almost impossible to get. Legal separation was offered as an option but was seldom used.

The Acadians were suspicious of outsiders and on occasion did not readily cooperate with census takers. The first reliable population figures for the area came with the census of 1671, which noted fewer than 450 people. By 1714, the Acadian population had expanded to 2,528 individuals, mostly from natural increase rather than immigration. Most Acadian women in the 18th century gave birth to living children an average of eleven times. Although these numbers are identical to those in Canada, 75% of Acadian children reached adulthood, many more than in other parts of New France. The isolation of the Acadian communities meant the people were not exposed to many of the imported epidemics, allowing the children to remain healthier.

In 1714, a few Acadian families emigrated to Île Royale

The Salvation Islands ( French: ''Îles du Salut'', so called because the missionaries went there to escape plague on the mainland), sometimes mistakenly called the Safety Islands, are a group of small islands of volcanic origin about off the co ...

. These families had little property. But for the majority of Acadians, they could not be enticed by the French government to abandon their family lands for an area which was unknown and uncultivated.

Some Acadians migrated to nearby Île Saint-Jean (now Prince Edward Island) to take advantage of the fertile cropland. In 1732, the island had 347 settlers but within 25 years its population had expanded to 5000 Europeans. Much of the population surge on Île Saint-Jean took place in the 1750s, as Acadians left during the rising tensions on peninsular Nova Scotia after the settlement of Halifax in 1749. Le Loutre played a role in these removals through acts of encouragement and threats. The exodus to Île Saint-Jean became a flood with refugees fleeing British-held territory after the initial expulsions of 1755.

In contemporary Atlantic Canada, it is estimated that there are 300,000 French-speaking Acadians. In addition, there is a diaspora of over three million Acadian descendants in the world, primarily in the United States, in Canada outside the Atlantic region, and in France.

Economy