Aberdaron on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aberdaron () is a

The church at Aberdaron had the ancient privilege of

The church at Aberdaron had the ancient privilege of

Aberdaron, Bardsey Island, Bodferin, Llanfaelrhys and Y Rhiw were

Aberdaron, Bardsey Island, Bodferin, Llanfaelrhys and Y Rhiw were

Aberdaron stands on the shore of Aberdaron Bay in a small valley at the confluence of the Afon Daron and Afon Cyll-y-Felin, between the headlands of Uwchmynydd to the west and Trwyn y Penrhyn to the east. At the mouth of the bay stand two islands, ''Ynys Gwylan-Fawr'' and ''Ynys Gwylan-Fach'', which are known together as Ynysoedd Gwylanod (). Gwylan-Fawr reaches 108 feet (33 metres) in height. The

Aberdaron stands on the shore of Aberdaron Bay in a small valley at the confluence of the Afon Daron and Afon Cyll-y-Felin, between the headlands of Uwchmynydd to the west and Trwyn y Penrhyn to the east. At the mouth of the bay stand two islands, ''Ynys Gwylan-Fawr'' and ''Ynys Gwylan-Fach'', which are known together as Ynysoedd Gwylanod (). Gwylan-Fawr reaches 108 feet (33 metres) in height. The  East of Y Rhiw is an extensive low-lying plateau between and above sea level. The coastal rock is softer here and the sea has been free to erode the rock and

East of Y Rhiw is an extensive low-lying plateau between and above sea level. The coastal rock is softer here and the sea has been free to erode the rock and

Sheep have been raised in the

Sheep have been raised in the

. Rhiw. Retrieved 16 August 2009 There were two fulling mills on the Afon Daron, in addition to three corn mills, and

. Rhiw. Retrieved 16 August 2009 Tourism began to develop after 1918. The first tourist guide to the village was published in 1910 and extolled the virtues of "the salubrious sea and mountain breezes"; in addition to the two hotels in the village, local farmhouses took in visitors, which provided an extra source of income. At the 2001 Census, 59.4% of the population were in employment, 23.5% were self-employed, the unemployment rate was 2.3% and 16.0% were retired. Of those employed, 17.7% worked in agriculture; 15.8% in the wholesale and retail trades; 10.7% in construction; and 10.5% in education. Those working from home amounted to 32.3%, 15.2% travelled less than to their place of work and 23.6% travelled more than . The community is included in ''Pwllheli and Llŷn Regeneration Area'' and was identified in the ''Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation 2005'' as the electoral division in

Two stone bridges, Pont Fawr () and Pont Fach (), built in 1823, cross the Afon Daron and Afon Cyll y Felin in the centre of Aberdaron. Beyond the bridges, the road opens up to create a small market square. The Old Post Office was designed by

Two stone bridges, Pont Fawr () and Pont Fach (), built in 1823, cross the Afon Daron and Afon Cyll y Felin in the centre of Aberdaron. Beyond the bridges, the road opens up to create a small market square. The Old Post Office was designed by

. BBC. 31 March 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2009 and a small

. BBC. 3 May 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2009 Bardsey Island Trust bought the island in 1979 after an appeal supported by the

Porth Ysgo, owned by the National Trust, is reached by a steep slope from Llanfaelrhys, east of Aberdaron, past a disused manganese mine in Nant y Gadwen. The mine employed 200 people in 1906; the ore was used as a strengthening agent for steel. The mine closed in 1927, and produced in its lifetime. Where the path from Ysgo reaches the beach, a waterfall, Pistyll y Gaseg, tumbles over the cliff. At the eastern end of the bay is Porth Alwm, where the stream from Nant y Gadwen flows into the sea. The south-facing beach is composed of fine, firm sand.

To the west,

Porth Ysgo, owned by the National Trust, is reached by a steep slope from Llanfaelrhys, east of Aberdaron, past a disused manganese mine in Nant y Gadwen. The mine employed 200 people in 1906; the ore was used as a strengthening agent for steel. The mine closed in 1927, and produced in its lifetime. Where the path from Ysgo reaches the beach, a waterfall, Pistyll y Gaseg, tumbles over the cliff. At the eastern end of the bay is Porth Alwm, where the stream from Nant y Gadwen flows into the sea. The south-facing beach is composed of fine, firm sand.

To the west,

Porthor () is a

Porthor () is a

. The National Trust. Retrieved 16 August 2009 On the hill summits that dot the headlands are heather and

. Gwynedd Archaeological Trust. Retrieved 16 August 2009 It provided fuel from peat cuttings, pasture for animals and accommodated squatters, mainly fishermen, who had encroached on the common with the tacit acceptance of the community. An

. Gwynedd Archaeological Trust. Retrieved 16 August 2009 Castell Odo, on Mynydd Ystum, is one of Europe's earliest Iron Age Settlements, standing above sea level. The

Cymunedau’n Gyntaf Pen Llŷn. Retrieved 16 August 2009 To the east of the village, Felin Uchaf is an educational centre exploring ways of living and working in partnership with the environment. Developed on a redundant farm, it provides residential courses in rural skills and sustainable agriculture. A traditional Iron Age roundhouse has been built on the site.

Cymunedau’n Gyntaf Pen Llŷn. Retrieved 16 August 2009 The former Coastguard lookout point, manned for almost 80 years before becoming redundant in 1990, provides views over Bardsey Sound to the island. The hut contains an exhibition to the natural history of the area and a mural created by local children.. The National Trust. 2 April 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2009 The headland at Braich y Pwll is the only known location on the British mainland of the spotted rock rose,"The Llŷn Peninsula"

. The National Trust. Retrieved 16 August 2009 which produces bright yellow petals that last only one day. The coast here has open grass heath land and mountain, giving way to rugged sea cliffs and coves. There is a profusion of wildlife; it is an ideal vantage point to watch the spring and autumn bird migrations. Above the sea cliffs are the remains of Capel Mair (),"Llŷn Coastal Path: Some Places of Interest Along the Path"

Above the sea cliffs are the remains of Capel Mair (),"Llŷn Coastal Path: Some Places of Interest Along the Path"

. Cyngor Gwynedd. Retrieved 16 August 2009 where it was customary for pilgrims to invoke the protection of the

Cymunedau’n Gyntaf Pen Llŷn. Retrieved 16 August 2009 The traditional embarkation point for pilgrims crossing to Bardsey Island was at Porth Meudwy (), now a lobster fishing cove. Further south is Porth y Pistyll, which has good views of Ynysoedd Gwylanod, home to puffin and guillemot colonies; and Pen y Cil, where the

. The National Trust. Retrieved 16 August 2009

The mountain-top hamlet of Y Rhiw is to the east. There are fine views of Llŷn Peninsula, Llŷn towards

The mountain-top hamlet of Y Rhiw is to the east. There are fine views of Llŷn Peninsula, Llŷn towards

. Cyngor Gwynedd. Retrieved 16 August 2009 and Neolithic quarries. Nearby on Mynydd y Graig are three hillforts in Britain, hillforts, several hut circles and terraced fields that are thought to date from the late Iron Age; in 1955, a

. Rhiw. Retrieved 16 August 2009 Bwlch y Garreg Wen at Y Rhiw, built in 1731, is a ''croglofft'' cottage, a type of agricultural worker's house found in Llŷn Peninsula, Llŷn.

Aberdaron lies at the western end of the B roads in Zone 4 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, B4413 road. The road runs east to Llanbedrog, where it connects with the A499 road, A499

Aberdaron lies at the western end of the B roads in Zone 4 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, B4413 road. The road runs east to Llanbedrog, where it connects with the A499 road, A499

Aberdaron is a predominantly Welsh-speaking community; 75.2% of the population speak the language. A mobile library visits a number of sites in the community each week; and :cy:Llanw Llŷn, Llanw Llŷn, a :cy:papur bro, papur bro published in Abersoch, serves the area; the local English newspapers are the ''Caernarfon and Denbigh Herald'', published in Caernarfon; and the ''Cambrian News'', published in Aberystwyth. Summer harp recitals and concerts are held in St Hywyn's Church; Gŵyl Pen Draw'r Byd () is an annual event, which includes beach side concerts and competitions on the shore, with an evening concert at Morfa Mawr Farm; Gŵyl Pentre Coll (), a festival of contemporary acoustic music, has been held since 2008 at Felin Uchaf in Rhoshirwaun; and a local eisteddfod, Eisteddfod Flynyddol Uwchmynydd, is held at Ysgol Crud y Werin.

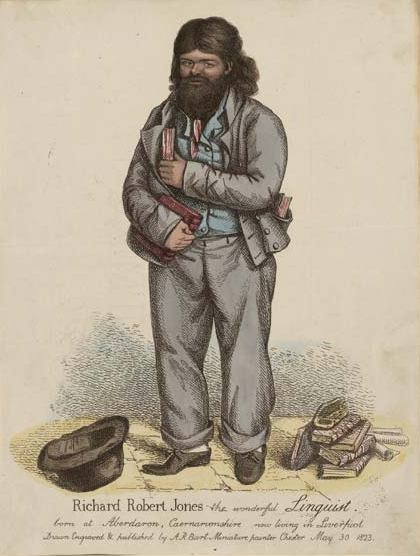

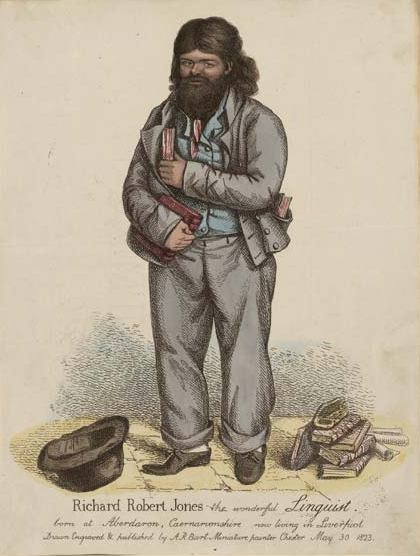

The poet R. S. Thomas was the vicar of St Hywyn's Church from 1967 to 1978; when he retired, he lived for some years in Y Rhiw. An ardent Welsh nationalist who learned to speak Welsh, his poetry was based on his religious faith. In 1995, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and he was widely regarded as the best religious poet of his time. A festival devoted to the work of RS Thomas and his wife, the artist ME Eldridge, takes place in the village every June. The subject of one of Thomas's poems, Richard Robert Jones, better known as "Dic Aberdaron", was born in the village in 1780. Despite very little formal education, he is said to have been fluent in 14 languages and spent years traveling the country accompanied by his books and his cat.

William Rowlands won a prize at the National Eisteddfod in 1922, for an adventure story written for boys. The book, ''Y Llong Lo'' (), was published in 1924, and told the story of two boys who stow away on one of the ships that brought coal to Porth Neigwl.

During the early 1920s, South African poetry, South African poet Roy Campbell (poet), Roy Campbell and his aristocratic English wife Mary Garman lived in a ''croglofft'' cottage" above Porth Ysgo."Love in a Hut"

Aberdaron is a predominantly Welsh-speaking community; 75.2% of the population speak the language. A mobile library visits a number of sites in the community each week; and :cy:Llanw Llŷn, Llanw Llŷn, a :cy:papur bro, papur bro published in Abersoch, serves the area; the local English newspapers are the ''Caernarfon and Denbigh Herald'', published in Caernarfon; and the ''Cambrian News'', published in Aberystwyth. Summer harp recitals and concerts are held in St Hywyn's Church; Gŵyl Pen Draw'r Byd () is an annual event, which includes beach side concerts and competitions on the shore, with an evening concert at Morfa Mawr Farm; Gŵyl Pentre Coll (), a festival of contemporary acoustic music, has been held since 2008 at Felin Uchaf in Rhoshirwaun; and a local eisteddfod, Eisteddfod Flynyddol Uwchmynydd, is held at Ysgol Crud y Werin.

The poet R. S. Thomas was the vicar of St Hywyn's Church from 1967 to 1978; when he retired, he lived for some years in Y Rhiw. An ardent Welsh nationalist who learned to speak Welsh, his poetry was based on his religious faith. In 1995, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and he was widely regarded as the best religious poet of his time. A festival devoted to the work of RS Thomas and his wife, the artist ME Eldridge, takes place in the village every June. The subject of one of Thomas's poems, Richard Robert Jones, better known as "Dic Aberdaron", was born in the village in 1780. Despite very little formal education, he is said to have been fluent in 14 languages and spent years traveling the country accompanied by his books and his cat.

William Rowlands won a prize at the National Eisteddfod in 1922, for an adventure story written for boys. The book, ''Y Llong Lo'' (), was published in 1924, and told the story of two boys who stow away on one of the ships that brought coal to Porth Neigwl.

During the early 1920s, South African poetry, South African poet Roy Campbell (poet), Roy Campbell and his aristocratic English wife Mary Garman lived in a ''croglofft'' cottage" above Porth Ysgo."Love in a Hut"

. Rhiw. Retrieved 16 August 2009 According to his biographer, Joseph Pearce, Roy and Mary Campbell shocked the local population with their flashy, colourful clothing, unkempt appearances and lack of bashfulness about nudity and sex. Furthermore, the Campbell's first child, their daughter Teresa, was born, with assistance of a local midwife, inside the cottage during the stormy night of 26 November 1922. Campbell's first widely successful and popular poem, ''The Flaming Terrapin'', was completed in the cottage and mailed to its publisher from Aberdaron, after which Campbell was widely praised and long afterward considered to be one of the best poets of the Interwar period. Considered one of the most significant Welsh poets of the 15th century, Dafydd Nanmor, in ''Gwallt Llio'', compared the striking yellow colour of the rocks at Uwchmynydd, covered by golden hair lichen, to the colour of his loved one's hair. Lewys Daron, a 16th-century poet best known for his elegy to friend and fellow poet Tudur Aled, is thought to have been born in Aberdaron. In the 18th century Alice Griffith, Anne Griffith was a local healer who was an early advocate of the use of fox-glove for heart conditions. She was born in 1734 and lived all her adult life at Bryn Canaid in Uwchmynydd, where she would collect plants, cheese, apple mold and local manganese to make remedies. She died in 1821, but details are known of her work due to a local historian.

Yorkshire-born poet Christine Evans (poet), Christine Evans lives half the year on Bardsey Island and spends the winters at Uwchmynydd. She moved to Pwllheli as a teacher and married into a Bardsey Island farming family. On maternity leave in 1976, she started writing poems; her first book was published seven years later. ''Cometary Phrases'' was Welsh Book of the Year 1989 and she was the winner of the inaugural Roland Mathias Prize in 2005.

Edgar Ewart Pritchard, an amateur film-maker from Brownhills, produced ''The Island in the Current'', a colour film of life on Bardsey Island, in 1953; a copy of the film is held by the National Screen and Sound Archive of Wales. A candle lantern, discovered in 1946 in a cowshed at Y Rhiw, is now displayed in St Fagans National History Museum;"Snippets VI"

Considered one of the most significant Welsh poets of the 15th century, Dafydd Nanmor, in ''Gwallt Llio'', compared the striking yellow colour of the rocks at Uwchmynydd, covered by golden hair lichen, to the colour of his loved one's hair. Lewys Daron, a 16th-century poet best known for his elegy to friend and fellow poet Tudur Aled, is thought to have been born in Aberdaron. In the 18th century Alice Griffith, Anne Griffith was a local healer who was an early advocate of the use of fox-glove for heart conditions. She was born in 1734 and lived all her adult life at Bryn Canaid in Uwchmynydd, where she would collect plants, cheese, apple mold and local manganese to make remedies. She died in 1821, but details are known of her work due to a local historian.

Yorkshire-born poet Christine Evans (poet), Christine Evans lives half the year on Bardsey Island and spends the winters at Uwchmynydd. She moved to Pwllheli as a teacher and married into a Bardsey Island farming family. On maternity leave in 1976, she started writing poems; her first book was published seven years later. ''Cometary Phrases'' was Welsh Book of the Year 1989 and she was the winner of the inaugural Roland Mathias Prize in 2005.

Edgar Ewart Pritchard, an amateur film-maker from Brownhills, produced ''The Island in the Current'', a colour film of life on Bardsey Island, in 1953; a copy of the film is held by the National Screen and Sound Archive of Wales. A candle lantern, discovered in 1946 in a cowshed at Y Rhiw, is now displayed in St Fagans National History Museum;"Snippets VI"

. Rhiw. Retrieved 16 August 2009 and

. Bardsey Island Trust. Retrieved 16 August 2009 Since 1999, Bardsey Island Trust has appointed an ''Artist in Residence'' to spend several weeks on the island producing work which is later exhibited on the mainland. A Welsh literary residence was created in 2002; singer-songwriter Fflur Dafydd spent six weeks working on a collection of poetry and prose. Her play ''Hugo'' was inspired by her stay, and she has produced two novels, ''Atyniad'' (), which won the prose medal at the 2006 Eisteddfod; and ''Twenty Thousand Saints'', winner of the Oxfam Hay Prize, which tells how the women of the island, starved of men, turn to each other. It was tradition for Bardsey Island to elect the "King of Bardsey" () and, from 1820 onwards, he would be crowned by Baron Newborough or his representative;"Kings of Bardsey"

. Cimwch. Retrieved 16 August 2009 the crown is now kept at Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool, although calls have been made for it to return to Gwynedd. At the outbreak of the First World War, the last king, Love Pritchard, offered himself and the men of the island for military service, but he was refused as he was considered too old at the age of 71; Pritchard took umbrage and declared the island to be a neutral power. In 1925 Pritchard left the island for the mainland, to seek a less laborious way of life, but died the following year. Owen Griffith, a qualified pharmacist from Penycaerau, who was known as the "Doctor of the Wild Wart", used a traditional herbalist remedy to cure basal cell carcinoma, also known as rodent ulcer; the remedy had supposedly been passed on to the family 300 years earlier by an Irish Traveller, Irish tinker. In 1932, a woman died while receiving treatment and, even though the inquest into her death found that no blame was apportioned to the treatment, the Chief Medical Officer for Caernarfonshire vociferously condemned the treatment in the press. Former patients came out in support of the pharmacist and petitions were sent to the Department of Health demanding that a medical licence be granted to Griffith and his cousin. There are several folk tales of the Tylwyth Teg, the fairy people who inhabited the area and an invisible land in Cardigan Bay. One tells of a farmer from Aberdaron who was in the habit of stepping outside his house before retiring to bed. One night, he was spoken to by a stranger, who asked why the farmer was annoyed by him. The farmer, confused, asked what the stranger meant and was told to stand with one foot on the stranger's. This he did and could see another house, just below his own, and that all the farm's slops went down the chimney of the invisible house. The stranger asked if the farmer would move his door to the other side of the house, which the farmer subsequently did, walling up the original door; from that day, the farmer's livestock flourished and he became one of the most prosperous men in the area.

A church was founded in Aberdaron in the 6th century by Saint Hywyn, a follower of

A church was founded in Aberdaron in the 6th century by Saint Hywyn, a follower of

. The Edge of Wales Walk. Retrieved 16 August 2009 it was a significant institution, a monastery and centre of religious learning, rather than simply a place of worship for the locals. The present double-naved Church of St Hywyn, Aberdaron, Church of St Hywyn (), built in 1137 and known as the "Cathedral of Llŷn", stands above the shore and was on the pilgrim route to

. BBC. 3 April 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2009 and in the churchyard stand Y Meini Feracius a Senagus (), the tombstones of two 5th-century Christian priests, found in the 18th century on farmland near Mynydd Anelog. In 2008, the church became the centre of controversy when the new vicar Reverend Jim Cotter, Jim Cotter, himself gay, blessed a gay civil partnership. The vicar was reprimanded by Barry Morgan (bishop), Barry Morgan, the Archbishop of Wales. Referring to the archbishop's protests, the vicar stated "There was a bit of a to-do about it". The church at Llanfaelrhys is the only one in the United Kingdom dedicated to Saint Maelrhys, the cousin of both Saint Cadfan and Saint Hywyn, who accompanied them to Wales from

. Rhiw. Retrieved 16 August 2009 Two of the earliest non-conformist chapels in the Llŷn Peninsula were established at Penycaerau, in 1768, and Uwchmynydd, in 1770; the Congregationalists opened Cephas Independent Chapel in 1829; and Capel Nebo was built at Y Rhiw in 1813; the Methodist Church of Great Britain, Wesleyan Methodists followed in 1832 at Capel Pisgah. By 1850, there were eight non-conformist chapels in Aberdaron, five in Y Rhiw and one on Bardsey Island; but more were to be built. The Calvinistic Methodists opened Capel Tan y Foel; and Capel Bethesda, the Baptist chapel at Rhoshirwaun, was built in 1904. Aberdaron is also home to a Seventh-day Adventist Church, Seventh-day Adventist youth camp named Glan-yr-afon, located from the village centre. At the 2001 census, 73.9% of the population claimed to be Christians, Christian and 15.0% stated that they had no religion.

. Wales Sea Angling. Retrieved 16 August 2009 Access is difficult at Uwchmynydd, but pollock, mackerel, wrasse and European conger, conger are caught; spiny dogfish, huss are plentiful; and common ling, ling are found occasionally. The village is a popular hiking, walking centre and lies on the Llŷn Coastal Path, which runs from Caernarfon to Porthmadog as part of the Wales Coast Path. Kayaking is possible from both Aberdaron and Porth Neigwl, and the south-facing sunshine coast is a major attraction; there are campsite, camping facilities for canoeists on the shores of Porth Neigwl. The area has excellent underwater diving, diving. Underwater visibility at Bardsey Island extends to and there is a rich variety of sea life; it is considered some of the best diving in Gwynedd. The Ynysoedd Gwylanod are particularly popular and the wreck of the ''Glenocum'', in Bae Aberdaron, is excellent for novices, having a maximum depth of ; an extremely large European conger, conger eel lives in the lower section of the boiler openings. There is spectacular diving at Pen y Cil, where there is a slate wreck and an unusual cave dive; nearby Carreg Ddu is an isolated rocky island in Bardsey Sound, although care must be taken as there are strong currents.

Beachgoing is popular along the coast. Aberdaron Beach, facing south-west, is sandy, gently shelving and safe; it received a Keep Wales Tidy, Seaside Award in 2008. Porthor also attracts bathers and has sands which squeak when walked on; the beach at Porth Neigwl was awarded a Green Coast Award in 2009.

Aberdaron Beach is a surfing and bodyboarding location for surfers of all levels, although it can be dangerous at high tide when the waves break directly onto boulders underneath the cliff. The better surfers head for the northern end.

The area has excellent underwater diving, diving. Underwater visibility at Bardsey Island extends to and there is a rich variety of sea life; it is considered some of the best diving in Gwynedd. The Ynysoedd Gwylanod are particularly popular and the wreck of the ''Glenocum'', in Bae Aberdaron, is excellent for novices, having a maximum depth of ; an extremely large European conger, conger eel lives in the lower section of the boiler openings. There is spectacular diving at Pen y Cil, where there is a slate wreck and an unusual cave dive; nearby Carreg Ddu is an isolated rocky island in Bardsey Sound, although care must be taken as there are strong currents.

Beachgoing is popular along the coast. Aberdaron Beach, facing south-west, is sandy, gently shelving and safe; it received a Keep Wales Tidy, Seaside Award in 2008. Porthor also attracts bathers and has sands which squeak when walked on; the beach at Porth Neigwl was awarded a Green Coast Award in 2009.

Aberdaron Beach is a surfing and bodyboarding location for surfers of all levels, although it can be dangerous at high tide when the waves break directly onto boulders underneath the cliff. The better surfers head for the northern end.

A Vision of Britain Through Time

British History Online

British Listed Buildings

*

Geograph

Historical Directories

Office for National Statistics

Y Rhiw

{{Good article Aberdaron, Surfing locations in Wales

community

A community is a social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant characteristic, such as place, set of norms, culture, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given g ...

, electoral ward

A ward is a local authority area, typically used for electoral purposes. In some countries, wards are usually named after neighbourhoods, thoroughfares, parishes, landmarks, geographical features and in some cases historical figures connected t ...

and former fishing village

A fishing village is a village, usually located near a fishing ground, with an economy based on catching fish and harvesting seafood. The continents and islands around the world have coastlines totalling around 356,000 kilometres (221,000 ...

at the western tip of the Llŷn Peninsula

The Llŷn Peninsula ( or , ) is a peninsula in Gwynedd, Wales, with an area of about , and a population of at least 20,000. It extends into the Irish Sea, and its southern coast is the northern boundary of the Tremadog Bay inlet of Cardigan Ba ...

in the Welsh county of Gwynedd

Gwynedd () is a county in the north-west of Wales. It borders Anglesey across the Menai Strait to the north, Conwy, Denbighshire, and Powys to the east, Ceredigion over the Dyfi estuary to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. The ci ...

. It lies west of Pwllheli

Pwllheli ( ; ) is a market town and community on the Llŷn Peninsula (), in Gwynedd, north-west Wales. It had a population of 4,076 in 2011, which declined slightly to 3,947 in 2021; a large proportion (81%) were Welsh language, Welsh speaking. ...

and south-west of Caernarfon

Caernarfon (; ) is a List of place names with royal patronage in the United Kingdom, royal town, Community (Wales), community and port in Gwynedd, Wales. It has a population of 9,852 (with Caeathro). It lies along the A487 road, on the easter ...

; as of 2021, it has a population of 896. The community includes Bardsey Island

Bardsey Island (), known as the legendary "Island of 20,000 Saints", is located off the Llŷn Peninsula in the Wales, Welsh county of Gwynedd. The Welsh language, Welsh name means "The Island in the Currents", while its English name refers to t ...

(), the coastal area around Porthor, and the villages of Anelog, Llanfaelrhys, Penycaerau, Rhoshirwaun, Rhydlios, Uwchmynydd and Y Rhiw. It covers an area of just under 50 square kilometres.

Y Rhiw and Llanfaelrhys have long been linked by sharing rectors and by their close proximity, but were originally ecclesiastical parishes in themselves. The parish of Bodferin/Bodverin was assimilated in the 19th century. The village was the last rest stop for pilgrims heading to Bardsey Island (Ynys Enlli), the legendary "island of 20,000 saints". In the 18th and 19th centuries, it developed as a shipbuilding centre and port. The mining and quarrying industries became major employers, and limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

, lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

, jasper

Jasper, an aggregate of microgranular quartz and/or cryptocrystalline chalcedony and other mineral phases, is an opaque, impure variety of silica, usually red, yellow, brown or green in color; and rarely blue. The common red color is due to ...

and manganese

Manganese is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese was first isolated in the 1770s. It is a transition m ...

(''Mango'') were exported. There are the ruins of an old pier running out to sea at Porth Simdde, which is the local name for the west end of Aberdaron Beach. After the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the mining industry collapsed and Aberdaron gradually developed into a holiday resort. The beach was awarded a Seaside Award

Keep Wales Tidy is a Welsh national voluntary environmental charity which works towards achieving "a clean, safe and tidy Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is border ...

in 2008.

The coastal waters are part of Pen Llŷn a'r Sarnau Special Area of Conservation, one of the largest marine designated sites in the United Kingdom. The coast itself forms part of the Aberdaron Coast and Bardsey Island Special Protection Area and was designated a Heritage Coast

A heritage coast is a strip of coastline in England and Wales, the extent of which is defined by agreement between the relevant statutory national agency and the relevant local authority. Such areas are recognised for their natural beauty, wildlife ...

in 1974. In 1956, the area was included in Llŷn Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty

An Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB; , AHNE) is one of 46 areas of countryside in England, Wales, or Northern Ireland that has been designated for conservation due to its significant landscape value. Since 2023, the areas in England an ...

. Conservation Areas have been created in Aberdaron, Bardsey Island and Y Rhiw; the area has been designated a Landscape of Historic Interest.

Etymology

''Aberdaron'' means "Mouth of the Daron river", a reference to the river () which flows into the sea at Aberdaron Bay. The river itself is named after ''Daron'', an ancient Celtic goddess of oak trees, with ''Dâr'' being an archaic Welsh word for oak. As such, the name shares an etymology withAberdare

Aberdare ( ; ) is a town in the Cynon Valley area of Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wales, at the confluence of the Rivers Dare (Dâr) and River Cynon, Cynon. Aberdare has a population of 39,550 (mid-2017 estimate). Aberdare is south-west of Merthyr Tydf ...

and the Dare river ().

Prehistory

The area around Aberdaron has been inhabited by people for millennia. Evidence from theIron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

hillfort

A hillfort is a type of fortification, fortified refuge or defended settlement located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typical of the late Bronze Age Europe, European Bronze Age and Iron Age Europe, Iron Age. So ...

at Castell Odo, on Mynydd Ystum, shows that some phases of its construction began unusually early, in the late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, between 2850 and 2650 years before present (BP). The construction was wholly defensive but, in later phases, defence appears to have been less important; in the last phase, the fort's ramparts were deliberately flattened, suggesting there was no longer a need for defence. The Bronze and Iron Age double-ringed fortification at Meillionnydd was occupied intensively from at least the 8/7th to the 3rd/2nd century BCE and was also deliberately flattened. It appears that Aberdaron became an undefended farming community. Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

calls the Llŷn Peninsula

The Llŷn Peninsula ( or , ) is a peninsula in Gwynedd, Wales, with an area of about , and a population of at least 20,000. It extends into the Irish Sea, and its southern coast is the northern boundary of the Tremadog Bay inlet of Cardigan Ba ...

''Ganganorum Promontorium'' (); the Gangani were a tribe of Celts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

also found in Ireland and it is thought there may have been strong ties with Leinster

Leinster ( ; or ) is one of the four provinces of Ireland, in the southeast of Ireland.

The modern province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige, which existed during Gaelic Ireland. Following the 12th-century ...

.

History

The church at Aberdaron had the ancient privilege of

The church at Aberdaron had the ancient privilege of sanctuary

A sanctuary, in its original meaning, is a sacred space, sacred place, such as a shrine, protected by ecclesiastical immunity. By the use of such places as a haven, by extension the term has come to be used for any place of safety. This seconda ...

. In 1094, Gruffudd ap Cynan

Gruffudd ap Cynan (–1137) was List of rulers of Gwynedd, King of Gwynedd from 1081 until his death in 1137. In the course of a long and eventful life, he became a key figure in Welsh resistance to House of Normandy, Norman rule.

As a descen ...

, the exiled King of Gwynedd, sought refuge in the church while attempting to recapture his throne; he escaped in the monastic community's boat to Ireland. He regained his territories in 1101 and, in 1115, Gruffydd ap Rhys

Gruffydd ap Rhys (c. 1090 – 1137) was Prince of Deheubarth, in Wales. His sister was the Princess Nest ferch Rhys. He was the father of Rhys ap Gruffydd, known as 'The Lord Rhys', who was one of the most successful rulers of Deheubarth during ...

, the exiled prince of Deheubarth

Deheubarth (; , thus 'the South') was a regional name for the Welsh kingdoms, realms of south Wales, particularly as opposed to kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd (Latin: ''Venedotia''). It is now used as a shorthand for the various realms united under ...

, took refuge at Aberdaron to escape capture by Gwynedd's ruler. Henry I of England

Henry I ( – 1 December 1135), also known as Henry Beauclerc, was King of England from 1100 to his death in 1135. He was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and was educated in Latin and the liberal arts. On William's death in 1087, Henr ...

had invaded Gwynedd the previous year and, faced by an overwhelming force, Gruffudd ap Cynan had been forced to pay homage and a substantial fine to Henry. The King of Gwynedd, seeking to give up the exiled prince to Henry, ordered that the fugitive prince be dragged from the church by force, but his soldiers were beaten back by the local clergy; Gruffydd ap Rhys escaped under cover of night and fled south to join up with his supporters in Ystrad Tywi

Ystrad Tywi (, ''Valley of the river Towy'') is a region of southwest Wales situated on both banks of the River Towy (), it contained places such as Cedweli, Carnwyllion, Loughor, Llandeilo, and Gwyr (although this is disputed). Although ...

.

Following the conquest of Gwynedd, in 1284, Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 125 ...

set about touring his new territories. He visited the castles at Conwy

Conwy (, ), previously known in English as Conway, is a walled market town, community and the administrative centre of Conwy County Borough in North Wales. The walled town and castle stand on the west bank of the River Conwy, facing Deganwy ...

and Caernarfon

Caernarfon (; ) is a List of place names with royal patronage in the United Kingdom, royal town, Community (Wales), community and port in Gwynedd, Wales. It has a population of 9,852 (with Caeathro). It lies along the A487 road, on the easter ...

. Court was held at Nefyn

Nefyn (, archaically anglicised as Nevin) is a town and community (Wales), community on the northwest coast of the Llŷn Peninsula, Gwynedd, Wales. Nefyn is popular with visitors for its sandy beach, and has one substantial hotel, a community pu ...

, at which his new subjects were expected to demonstrate their loyalty; he visited Aberdaron on his way to Bardsey Abbey.

The medieval townships of Aberdaron were Isseley (Bugelis, Rhedynfra, Dwyros, Anhegraig, Cyllyfelin, Gwthrian, Deuglawdd and Bodernabdwy), Uwchseley (Anelog, Pwlldefaid, Llanllawen, Ystohelig, Bodermid, Trecornen), Ultradaron (Penrhyn, Cadlan, Ysgo, Llanllawen) and Bodrydd (Penycaerau, Bodrydd, Bodwyddog). These locatives predate the idea of the modern ecclesiastical parish; some were or became hamlets in themselves, whereas others have subsequently been divided. for example, the modern Bodrydd Farm is only a part of the medieval township.

After the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, when the Parliamentarians under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

introduced a strongly Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

regime, Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

remained the dominant religion in the area. Catholics, who had largely supported the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

side, were often considered to be traitors and efforts were made to eradicate the religion. The persecution even extended to Aberdaron and, in 1657, Gwen Griffiths of Y Rhiw was summoned to the Quarter Sessions

The courts of quarter sessions or quarter sessions were local courts that were traditionally held at four set times each year in the Kingdom of England from 1388; they were extended to Wales following the Laws in Wales Act 1535. Scotland establ ...

as a "papist".

Agricultural improvement and the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

came to Aberdaron in the 19th century. The Inclosure (Consolidation) Act 1801 was intended to make it easier for landlords to enclose and improve common land, introduce increased efficiency, bring more land under the plough and reduce the high prices of agricultural production. Rhoshirwaun Common, following strong opposition, was enclosed in 1814; the process was not completed in Aberdaron, Llanfaelrhys and Y Rhiw until 1861. On the industrial front, mining developed as a major source of employment, especially at Y Rhiw, where manganese

Manganese is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese was first isolated in the 1770s. It is a transition m ...

was discovered in 1827.

During the Second World War, Y Rhiw played a vital role in preparations for the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and ...

. A team of electronic engineers set up an experimental ultra high frequency

Ultra high frequency (UHF) is the ITU designation for radio frequencies in the range between 300 megahertz (MHz) and 3 gigahertz (GHz), also known as the decimetre band as the wavelengths range from one meter to one tenth of a meter ...

radio station, from where they were able to make a direct link to stations in Fishguard

Fishguard (, meaning "Mouth of the River Gwaun") is a coastal town in Pembrokeshire, Wales, with a population of 3,400 (rounded to the nearest 100) as of the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 census. Modern Fishguard consists of two parts, Lowe ...

and Llandudno

Llandudno (, ) is a seaside resort, town and community (Wales), community in Conwy County Borough, Wales, located on the Creuddyn peninsula, which protrudes into the Irish Sea. In the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 UK census, the community � ...

. The system employed a frequency that the German forces were unable to either monitor or jam, and was used in the 1944 landings.

Governance

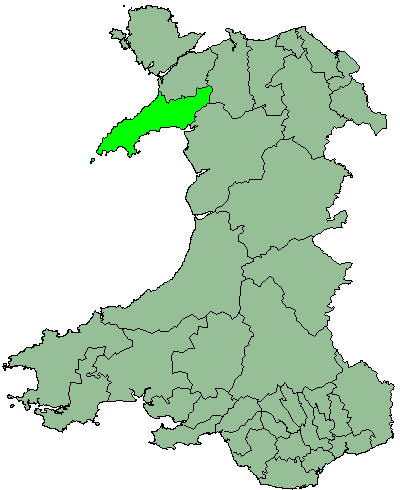

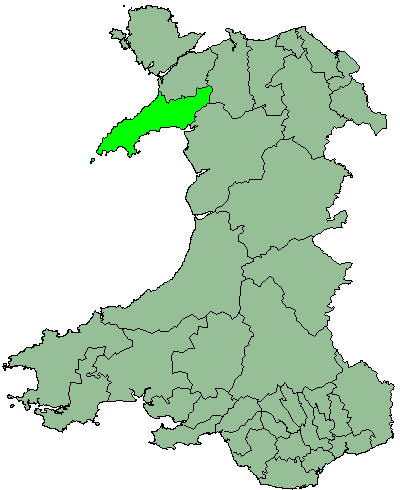

Aberdaron, Bardsey Island, Bodferin, Llanfaelrhys and Y Rhiw were

Aberdaron, Bardsey Island, Bodferin, Llanfaelrhys and Y Rhiw were civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government. Civil parishes can trace their origin to the ancient system of parishes, w ...

es in the commote

A commote (, sometimes spelt in older documents as , plural , less frequently )'' Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru'' (University of Wales Dictionary), p. 643 was a secular division of land in Medieval Wales. The word derives from the prefix ("together" ...

of Cymydmaen within Cantref Llŷn, in Caernarfonshire

Caernarfonshire (; , ), previously spelled Caernarvonshire or Carnarvonshire, was one of the thirteen counties of Wales that existed from 1536 until their abolishment in 1974. It was located in the north-west of Wales.

Geography

The county ...

. Following the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 (4 & 5 Will. 4. c. 76) (PLAA) known widely as the New Poor Law, was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed by the British Whig Party, Whig government of Charles ...

, parishes were grouped into "unions": Pwllheli Poor Law Union was created in 1837. Under the Public Health Act 1848

A local board of health (or simply a ''local board'') was a local authority in urban areas of England and Wales from 1848 to 1894. They were formed in response to cholera epidemics and were given powers to control sewers, clean the streets, regulat ...

the area of the poor law union became Pwllheli Rural Sanitary District, which from 1889 formed a second tier of local government under Caernarfonshire County Council. Y Rhiw was absorbed into the smaller Llanfaelrhys in 1886; and under the Local Government Act 1894

The Local Government Act 1894 ( 56 & 57 Vict. c. 73) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in England and Wales outside the County of London. The act followed the reforms carried out at county leve ...

the four remaining parishes became part of Llŷn Rural District. Bodferin, Llanfaelrhys, and parts of Bryncroes and Llangwnnadl, were amalgamated into Aberdaron in 1934. Llŷn Rural District was abolished in 1974 and Bardsey Island was absorbed into Aberdaron; this formed a community

A community is a social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant characteristic, such as place, set of norms, culture, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given g ...

within Dwyfor District in the new county

A county () is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesL. Brookes (ed.) '' Chambers Dictionary''. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, 2005. in some nations. The term is derived from the Old French denoti ...

of Gwynedd

Gwynedd () is a county in the north-west of Wales. It borders Anglesey across the Menai Strait to the north, Conwy, Denbighshire, and Powys to the east, Ceredigion over the Dyfi estuary to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. The ci ...

; Dwyfor was abolished as a local authority area when Gwynedd became a unitary authority

A unitary authority is a type of local government, local authority in New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Unitary authorities are responsible for all local government functions within its area or performing additional functions that elsewhere are ...

in 1996.

The community now forms an electoral division

An electoral (congressional, legislative, etc.) district, sometimes called a constituency, riding, or ward, is a geographical portion of a political unit, such as a country, state or province, city, or administrative region, created to provid ...

of Gwynedd Council

Gwynedd Council, which calls itself by its Welsh name , is the governing body for the county of Gwynedd, one of the principal areas of Wales. The council administrates internally using the Welsh language.

History

The county of Gwynedd was c ...

, electing one councillor; William Gareth Roberts of Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru ( ; , ; officially Plaid Cymru – the Party of Wales, and often referred to simply as Plaid) is a centre-left, Welsh nationalist list of political parties in Wales, political party in Wales, committed to Welsh independence from th ...

was re-elected in 2008. Aberdaron Community Council has 12 elected members, who represent three wards: Aberdaron De (), Aberdaron Dwyrain () and Aberdaron Gogledd (). Ten Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in Pennsylvania, United States

* Independentes (English: Independents), a Portuguese artist ...

councillors and one from Plaid Cymru were elected unopposed in the 2008 election.

From 1950, Aberdaron was part of Caernarfon

Caernarfon (; ) is a List of place names with royal patronage in the United Kingdom, royal town, Community (Wales), community and port in Gwynedd, Wales. It has a population of 9,852 (with Caeathro). It lies along the A487 road, on the easter ...

UK parliamentary constituency; in 2010, the community was transferred to Dwyfor Meirionnydd constituency. In the Senedd

The Senedd ( ; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, Its role is to scrutinise the Welsh Government and legislate on devolve ...

, it has formed part of the Dwyfor Meirionnydd constituency since 2007, represented by Dafydd Elis-Thomas

Dafydd Elis Elis-Thomas, Baron Elis-Thomas, (; 18 October 1946 – 7 February 2025) was a Welsh politician who served as the leader of Plaid Cymru from 1984 to 1991 and represented the Dwyfor Meirionnydd constituency in the Senedd from 199 ...

of Plaid Cymru, who was the Presiding Officer of the assembly until 2011. The constituency forms part of the electoral region of Mid and West Wales.

Geography

Aberdaron stands on the shore of Aberdaron Bay in a small valley at the confluence of the Afon Daron and Afon Cyll-y-Felin, between the headlands of Uwchmynydd to the west and Trwyn y Penrhyn to the east. At the mouth of the bay stand two islands, ''Ynys Gwylan-Fawr'' and ''Ynys Gwylan-Fach'', which are known together as Ynysoedd Gwylanod (). Gwylan-Fawr reaches 108 feet (33 metres) in height. The

Aberdaron stands on the shore of Aberdaron Bay in a small valley at the confluence of the Afon Daron and Afon Cyll-y-Felin, between the headlands of Uwchmynydd to the west and Trwyn y Penrhyn to the east. At the mouth of the bay stand two islands, ''Ynys Gwylan-Fawr'' and ''Ynys Gwylan-Fach'', which are known together as Ynysoedd Gwylanod (). Gwylan-Fawr reaches 108 feet (33 metres) in height. The Llŷn Peninsula

The Llŷn Peninsula ( or , ) is a peninsula in Gwynedd, Wales, with an area of about , and a population of at least 20,000. It extends into the Irish Sea, and its southern coast is the northern boundary of the Tremadog Bay inlet of Cardigan Ba ...

is a marine eroded platform, an extension of the Snowdonia

Snowdonia, or Eryri (), is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in North Wales. It contains all 15 mountains in Wales Welsh 3000s, over 3000 feet high, including the country's highest, Snowdon (), which i ...

massif, with a complex geology including Precambrian

The Precambrian ( ; or pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pC, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of t ...

rocks. The coastline is rocky, with crags, scree

Scree is a collection of broken rock fragments at the base of a cliff or other steep rocky mass that has accumulated through periodic rockfall. Landforms associated with these materials are often called talus deposits.

The term ''scree'' is ap ...

s and low cliffs; heather-covered hills are separated by valleys occupied by pastures.

To the east, Mynydd Rhiw, Mynydd y Graig and Mynydd Penarfynydd form a series of hog-back ridges of igneous

Igneous rock ( ), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rocks are formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava.

The magma can be derived from partial ...

rock that reaches the sea at Trwyn Talfarach. Above the ridges are topped by hard gabbro

Gabbro ( ) is a phaneritic (coarse-grained and magnesium- and iron-rich), mafic intrusive igneous rock formed from the slow cooling magma into a holocrystalline mass deep beneath the Earth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is ch ...

. At its northern end, Mynydd Rhiw rises to and is a Marilyn. The outcrop of Clip y Gylfinhir () looming above the village of Y Rhiw. Mynydd Penarfynydd is one of the best exposures of intrusive, layered, igneous rock in the British Isles.

boulder clay

Boulder clay is an unsorted agglomeration of clastic sediment that is unstratified and structureless and contains gravel of various sizes, shapes, and compositions distributed at random in a fine-grained matrix. The fine-grained matrix consists o ...

to form sand, resulting in the spacious beach of Porth Neigwl (or ''Hell's Mouth'').

West of Aberdaron, four peaks rise above the rocky shoreline at Uwchmynydd. ''Mynydd Anelog'' stands high and another Marilyn, ''Mynydd Mawr'' at ; ''Mynydd y Gwyddel'' rises to and ''Mynydd Bychestyn'' is above sea level.

Bardsey Island lies off Pen y Cil, where there is another Marilyn; ''Mynydd Enlli''. The island is wide and long. The north-east rises steeply from the sea to a height of . In contrast, the western plain comprises low and relatively flat, cultivated farmland; in the south, the island narrows to an isthmus

An isthmus (; : isthmuses or isthmi) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea count ...

, connecting to a peninsula.

The coast around Aberdaron has been the scene of many shipwrecks. In 1822, the Bardsey Island lighthouse tender was wrecked, with the loss of six lives; in 1752, the schooner ''John the Baptist'', carrying a cargo of oats from Wexford

Wexford ( ; archaic Yola dialect, Yola: ''Weiseforthe'') is the county town of County Wexford, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the ...

to Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, was wrecked on the beach at Aberdaron. The sailing ship ''Newry'', with 400 passengers bound from Warrenpoint to Québec

Quebec is Canada's largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, New Brunswick to the southeast and a coastal border ...

, was wrecked at Porth Orion in 1880. The crew abandoned the passengers, leaving just the captain, ship's mate and one sailor, assisted by three local men, to lead 375 men, women and children to safety. A great storm swept the country on 26 October 1859 and many ships were lost; nine were wrecked at Porthor, seven of them with complete loss of life. On the south coast, vessels were often driven ashore at Porth Neigwl by a combination of south westerly gales and treacherous offshore currents. The ''Transit'' was lost in 1839, the ''Arfestone'' in the following year and the ''Henry Catherine'' in 1866. The bay earned its English title, ''Hell's Mouth'', from its reputation for wrecks during the days of the sailing ship.

Aberdaron is noted for low levels of air pollution. The ''Gwynedd State of the Environment Report'' in 2004 found levels of sulphur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless gas with a pungent smell that is responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is r ...

, nitrogen dioxide

Nitrogen dioxide is a chemical compound with the formula . One of several nitrogen oxides, nitrogen dioxide is a reddish-brown gas. It is a paramagnetic, bent molecule with C2v point group symmetry. Industrially, is an intermediate in the s ...

and carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

to be very low, with particulates

Particulate matter (PM) or particulates are microscopic particles of solid or liquid matter suspension (chemistry), suspended in the atmosphere of Earth, air. An ''aerosol'' is a mixture of particulates and air, as opposed to the particulate ...

to be low. It is one of the few sites in the United Kingdom for golden hair lichen, a striking bright orange lichen that is very sensitive to air pollution. The climate is relatively mild and, because of the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude (North Carolin ...

, frosts are rare in winter.

Climate

Being situated at the west coast of the UK, Aberdaron has a distinctmaritime climate

An oceanic climate, also known as a marine climate or maritime climate, is the temperate climate sub-type in Köppen classification represented as ''Cfb'', typical of west coasts in higher middle latitudes of continents, generally featuring ...

, with mild winters and cool summers. That is not to say that extremes cannot occur; in fact, some extraordinary temperature extremes have been recorded:

* On 2 August 1995, Aberdaron equaled the highest ever August minimum temperature in Wales, at 22 °C, after recording the record high temperature for the village of 29.2 °C on the same day.

* On 20 December 1998, the maximum temperature at Aberdaron was below average at 5 °C. The very next day, the highest January temperature ever observed in the UK was recorded there, at 20.1 °C. Yet the average temperature for that day was just 6.4 °C.

* On 9 July 2009, Aberdaron equalled the lowest ever temperature for the UK for July, at -2.5 °C.

* All of the record lows, except for November and December, were recorded in 2009 and they were all below freezing.

Despite the fact that Aberdaron can have quite extreme weather, the number of frosts per year is very low, with an average of 5.9 days per year; this is comparable with coastal areas of Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

and Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

. The region, England NW and Wales N, averages 52.3 days, with December alone exceeding the average yearly amount of frost for Aberdaron. The village is generally quite windy throughout the year, particularly in autumn and winter. Sunshine amounts are higher than the Wales average. Rainfall is well below the Wales average.

Economy

Llŷn Peninsula

The Llŷn Peninsula ( or , ) is a peninsula in Gwynedd, Wales, with an area of about , and a population of at least 20,000. It extends into the Irish Sea, and its southern coast is the northern boundary of the Tremadog Bay inlet of Cardigan Ba ...

for over a thousand years; Aberdaron has produced and exported wool for many years. The main product locally was felt

Felt is a textile that is produced by matting, condensing, and pressing fibers together. Felt can be made of natural fibers such as wool or animal fur, or from synthetic fibers such as petroleum-based acrylic fiber, acrylic or acrylonitrile or ...

, produced by soaking the cloth in water and beating it with large wooden paddles until the wool formed a thick mat which could be flattened, dried and cut into lengths."Local Woollen Industry". Rhiw. Retrieved 16 August 2009 There were two fulling mills on the Afon Daron, in addition to three corn mills, and

lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

was gathered around Y Rhiw, from which a grey dye was extracted. Arable crops consisted mainly of wheat

Wheat is a group of wild and crop domestication, domesticated Poaceae, grasses of the genus ''Triticum'' (). They are Agriculture, cultivated for their cereal grains, which are staple foods around the world. Well-known Taxonomy of wheat, whe ...

, barley

Barley (), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikele ...

, oat

The oat (''Avena sativa''), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural). Oats appear to have been domesticated as a secondary crop, as their seeds ...

s and potato

The potato () is a starchy tuberous vegetable native to the Americas that is consumed as a staple food in many parts of the world. Potatoes are underground stem tubers of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'', a perennial in the nightshade famil ...

es. The field boundaries date back several centuries and are marked by walls, ''cloddiau'' and hedgerows: important habitats for a variety of wildlife.

Wrecking and smuggling supplemented local incomes. In 1743, John Roberts and Huw Bedward from Y Rhiw were found guilty of the murder of two shipwrecked sailors on the beach at Porth Neigwl on 6 January 1742 and were hanged; Jonathan Morgan had been killed by a knife thrust into the nape of his neck and Edward Halesham, described as a boy, had been choked to death. A ship claimed to be from France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

unloaded illicit tea and brandy at Aberdaron in 1767; it attempted to sell its cargo to the locals; a Revenue cutter discovered salt being smuggled at Porth Cadlan in 1809; a schooner en route from Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

to Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

was reported to have offloaded lace, tea, brandy and gin at Y Rhiw in 1824.

During the 19th century, good-quality limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

and a small amount of lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

ore were quarried in the village. Jasper

Jasper, an aggregate of microgranular quartz and/or cryptocrystalline chalcedony and other mineral phases, is an opaque, impure variety of silica, usually red, yellow, brown or green in color; and rarely blue. The common red color is due to ...

was mined at Carreg; granite was quarried at Porth y Pistyll; and there was a brickworks at Porth Neigwl. The main source of income, however, was herring fishing. A regular shipping service was operated to Liverpool, exporting pigs, poultry and eggs; the vessels returned laden with coal for the neighbourhood. Limestone was also imported and offloaded into the water at high tide, then collected from the beach when the tide went out. Lime was needed to reduce the acidity of the local soil and lime kilns

A lime kiln is a kiln used for the calcination of limestone (calcium carbonate) to produce the form of lime (material), lime called ''quicklime'' (calcium oxide). The chemical equation for this chemical reaction, reaction is: Calcium carbonat ...

were built on the beaches at Porthor, Porth Orion, Porth Meudwy, Aberdaron and Y Rhiw to convert the limestone to quicklime

Calcium oxide (formula: Ca O), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term '' lime'' connotes calcium-containin ...

. There was shipbuilding at Porth Neigwl, where the last ship, a sloop named the ''Ebenezer'', was built in 1841; at Porthor, which came to an end with the building of a schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

, the ''Sarah'', in 1842. Aberdaron's last ship, the sloop ''Victory'', had been built in 1792, and the last ship to come out of Porth Ysgo had been another sloop, the ''Grace'', in 1778.

The outbreak of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

resulted in a great demand for manganese

Manganese is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese was first isolated in the 1770s. It is a transition m ...

as a strengthening agent for steel. Ore had been discovered at Y Rhiw in 1827 and the industry became a substantial employer in the village; over of ore were extracted between 1840 and 1945, and in 1906 the industry employed 200 people."About". Rhiw. Retrieved 16 August 2009 Tourism began to develop after 1918. The first tourist guide to the village was published in 1910 and extolled the virtues of "the salubrious sea and mountain breezes"; in addition to the two hotels in the village, local farmhouses took in visitors, which provided an extra source of income. At the 2001 Census, 59.4% of the population were in employment, 23.5% were self-employed, the unemployment rate was 2.3% and 16.0% were retired. Of those employed, 17.7% worked in agriculture; 15.8% in the wholesale and retail trades; 10.7% in construction; and 10.5% in education. Those working from home amounted to 32.3%, 15.2% travelled less than to their place of work and 23.6% travelled more than . The community is included in ''Pwllheli and Llŷn Regeneration Area'' and was identified in the ''Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation 2005'' as the electoral division in

Gwynedd

Gwynedd () is a county in the north-west of Wales. It borders Anglesey across the Menai Strait to the north, Conwy, Denbighshire, and Powys to the east, Ceredigion over the Dyfi estuary to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. The ci ...

with least access to services; it was ranked 13th in Wales. An agricultural census in 2000 recorded 33,562 sheep, 4,380 calves, 881 beef cattle, 607 dairy cattle and 18 pigs; there were of growing crops.

Demography

Aberdaron had a population of 896 in 2021, of which 19.1% were below the age of 17 and 53.5% were over 65 years of age. In 2001, owner occupiers inhabited 53.7% of the dwellings, 21.7% were rented and 19.6% were holiday homes. Central heating was installed in 62.8% of dwellings, but 2.4% were without sole use of a bath, shower or toilet. The proportion of households without use of a vehicle was 14.3%, but 40.9% had two or more. The population was predominantly White British, 98.5% identified themselves as such in 2021, 71.9% were born in Wales and 26.9% in England. The 2021 census revealed that 70.4% of residents identify themselves as Welsh speakers.Landmarks

It is sometimes referred to as the "Land's End ofNorth Wales

North Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, region of Wales, encompassing its northernmost areas. It borders mid Wales to the south, England to the east, and the Irish Sea to the north and west. The area is highly mountainous and rural, with Snowdon ...

" or, in Welsh, ''Pendraw'r Byd'' (roughly "far end of the world").

Aberdaron

Portmeirion

Portmeirion (; ) is a folly*

*

* tourist village in Gwynedd, North Wales. It lies on the estuary of the River Dwyryd in the community (Wales), community of Penrhyndeudraeth, from Porthmadog and from Minffordd railway station. Portmeirion was d ...

architect Clough Williams-Ellis

Sir Bertram Clough Williams-Ellis, Order of the British Empire, CBE, Military Cross, MC (28 May 1883 – 9 April 1978) was a Welsh architect known chiefly as the creator of the Italianate architecture, Italianate village of Portmeirion in North ...

.

Y Gegin Fawr () was built in the 13th century, as a communal kitchen where pilgrims could claim a meal on their way to Bardsey Island. Aberdaron was the last place on the route for rest and refreshment and pilgrims often had to wait weeks in the village for a chance to cross the treacherous waters of Bardsey Sound ().

One mile up the road towards Porth Meudwy is Cae y Grogbren (), near to which is a large red rock. In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, the abbot from the monastery on Bardsey Island visited the rock to dispense justice to local criminals; if they were found guilty, the wrongdoer would be hanged and thrown into Pwll Ddiwaelod (). The pool is a kettle lake

A kettle (also known as a kettle hole, kettlehole, or pothole) is a depression or hole in an outwash plain formed by retreating glaciers or draining floodwaters. The kettles are formed as a result of blocks of dead ice left behind by retreating ...

, formed at the end of the Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages, and g ...

, when blocks of ice were trapped underground and melted to form round, deep pools.

Above the village, on the Afon Daron, stands ''Bodwrdda'', an early 16th-century stone-built house, which had a fulling

Fulling, also known as tucking or walking ( Scots: ''waukin'', hence often spelt waulking in Scottish English), is a step in woollen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of woven cloth (particularly wool) to eliminate ( lanolin) oils, ...

mill adjacent; two large brick-built wings were added later, giving an imposing three-storey facade containing 17th-century windows. To the south, Penrhyn Mawr is a substantial late-18th-century gable-fronted farmhouse.

The National Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

maintains a visitors' centre at Porth y Swnt, which was opened in 2014.

Bardsey Island

Bardsey Island, off the mainland, was inhabited inNeolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

times, and traces of hut circles remain. During the 5th century, the island became a refuge for persecuted Christians"Island of 20,000 Saints". BBC. 31 March 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2009 and a small

Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foot ...

monastery existed. Saint Cadfan

Cadfan (), was the 6th century founder-abbot of Tywyn (whose church is dedicated to him) and Bardsey, both in Gwynedd, Wales. He was said to have received the island of Bardsey from Einion Frenin, king of Llŷn, around 516 and to have serv ...

arrived from Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

in 516 and, under his guidance, St Mary's Abbey was built. For centuries, the island was important as "the holy place of burial for all the bravest and best in the land". Bards called it "the land of indulgences, absolution and pardon, the road to Heaven and the gate to Paradise", and, in medieval times, three pilgrimages to Bardsey Island were considered to be of equivalent benefit to the soul as one to Rome. In 1188, the abbey was still a Celtic institution but, by 1212 it belonged to the Augustinians

Augustinians are members of several religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written about 400 A.D. by Augustine of Hippo. There are two distinct types of Augustinians in Catholic religious orders dating back to the 12th–13 ...

. Many people still walk to Aberdaron and Uwchmynydd each year in the footsteps of the saints, although only ruins of the old abbey's 13th-century bell tower remain today. A Celtic cross

upright 0.75 , A Celtic cross symbol

The Celtic cross is a form of ringed cross, a Christian cross featuring a nimbus or ring, that emerged in the British Isles and Western Europe in the Early Middle Ages. It became widespread through its u ...

amidst the ruins commemorates the 20,000 saints reputed to be buried on the island.

The island was declared a national nature reserve in 1986 and is part of Aberdaron Coast and Bardsey Island Special Protection Area. It is now a favourite bird-watching

Birdwatching, or birding, is the observing of birds, either as a recreational activity or as a form of citizen science. A birdwatcher may observe by using their naked eye, by using a visual enhancement device such as binoculars or a telescop ...

location, on the migration routes of thousands of birds. Bardsey Bird and Field Observatory (), founded in 1953, nets and rings 8,000 birds each year to understand their migration patterns."Wildlife Haven". BBC. 3 May 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2009 Bardsey Island Trust bought the island in 1979 after an appeal supported by the

Church in Wales

The Church in Wales () is an Anglican church in Wales, composed of six dioceses.

The Archbishop of Wales does not have a fixed archiepiscopal see, but serves concurrently as one of the six diocesan bishops. The position is currently held b ...

and many Welsh academics and public figures. The trust is financed through membership subscriptions, grants and donations; it is dedicated to protecting the wildlife, buildings and archaeological sites of the island; promoting its artistic and cultural life; and encouraging people to visit as a place of natural beauty and pilgrimage. When, in 2000, the trust advertised for a tenant for the sheep farm on the island, they had 1,100 applications. The tenancy is now held by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) is a Charitable_organization#United_Kingdom, charitable organisation registered in Charity Commission for England and Wales, England and Wales and in Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator, ...

; and the land is managed to maintain the natural habitat. Oat

The oat (''Avena sativa''), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural). Oats appear to have been domesticated as a secondary crop, as their seeds ...

s, turnips and swedes

Swedes (), or Swedish people, are an ethnic group native to Sweden, who share a common ancestry, Culture of Sweden, culture, History of Sweden, history, and Swedish language, language. They mostly inhabit Sweden and the other Nordic countries, ...

are grown; goats

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a species of goat-antelope that is mostly kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the famil ...

, ducks

Duck is the common name for numerous species of waterfowl in the family (biology), family Anatidae. Ducks are generally smaller and shorter-necked than swans and goose, geese, which are members of the same family. Divided among several subfam ...

, geese

A goose (: geese) is a bird of any of several waterfowl species in the family Anatidae. This group comprises the genera '' Anser'' (grey geese and white geese) and ''Branta'' (black geese). Some members of the Tadorninae subfamily (e.g., Egyp ...

and chickens

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domesticated subspecies of the red junglefowl (''Gallus gallus''), originally native to Southeast Asia. It was first domesticated around 8,000 years ago and is now one of the most common and w ...

kept; and there is a mixed flock of sheep

Sheep (: sheep) or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are a domesticated, ruminant mammal typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to d ...

and Welsh Black cattle.

The Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society

Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC), formerly Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society in the UK, is a wildlife charity that is dedicated solely to the worldwide conservation and welfare of all whales, dolphins and porpoises (cetaceans). It ha ...

has been working on cetaceans

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

in the region. Several species, most notably bottlenose dolphin

The bottlenose dolphin is a toothed whale in the genus ''Tursiops''. They are common, cosmopolitan members of the family Delphinidae, the family of oceanic dolphins. Molecular studies show the genus contains three species: the common bot ...

s, can be observed from the shores.

Llanfaelrhys