A Brief History Of Time on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes'' is a book on

Hawking begins with an anecdote about a scientist lecturing on the universe. An old woman got up and said, "What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise." The scientist asked what the tortoise was standing on. She replied, "You're very clever young man, very clever. But it's turtles all the way down!" Hawking goes on to explain why we know better.

He discusses the history of

Hawking begins with an anecdote about a scientist lecturing on the universe. An old woman got up and said, "What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise." The scientist asked what the tortoise was standing on. She replied, "You're very clever young man, very clever. But it's turtles all the way down!" Hawking goes on to explain why we know better.

He discusses the history of

Hawking describes how physicists and astronomers calculated the relative distance of stars from the Earth. Sir

Hawking describes how physicists and astronomers calculated the relative distance of stars from the Earth. Sir

Hawking discusses how Heisenberg's uncertainty principle implies the

Hawking discusses how Heisenberg's uncertainty principle implies the  He describes the phenomenon of

He describes the phenomenon of

Hawking introduces the spin of particles. Particles can be divided into two groups. Fermions, or matter particles, have a spin of 1/2. Fermions follow

Hawking introduces the spin of particles. Particles can be divided into two groups. Fermions, or matter particles, have a spin of 1/2. Fermions follow  Gravity is thought to be carried by gravitons, massless particles with spin 2. The

Gravity is thought to be carried by gravitons, massless particles with spin 2. The

Hawking discusses

Hawking discusses

Hawking recalls a conference on cosmology at the Vatican, where he was given an audience with

Hawking recalls a conference on cosmology at the Vatican, where he was given an audience with

Photos of the first edition of ''A Brief History of Time''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Brief History Of Time, A 1988 non-fiction books Books by Stephen Hawking English-language non-fiction books Popular physics books Cosmology books Bantam Books books

cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

by the physicist Stephen Hawking

Stephen William Hawking (8January 194214March 2018) was an English theoretical physics, theoretical physicist, cosmologist, and author who was director of research at the Centre for Theoretical Cosmology at the University of Cambridge. Between ...

, first published in 1988.

Hawking writes in non-technical terms about the structure, origin, development and eventual fate of the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

. He talks about basic concepts like space

Space is a three-dimensional continuum containing positions and directions. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions. Modern physicists usually consider it, with time, to be part of a boundless ...

and time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

, building blocks that make up the universe (such as quark

A quark () is a type of elementary particle and a fundamental constituent of matter. Quarks combine to form composite particles called hadrons, the most stable of which are protons and neutrons, the components of atomic nucleus, atomic nuclei ...

s) and the fundamental forces that govern it (such as gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

). He discusses two theories, general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity, and as Einstein's theory of gravity, is the differential geometry, geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of grav ...

and quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

that form the foundation of modern physics. Finally, he talks about the search for a unified theory that consistently describes everything in the universe.

The book became a bestseller

A bestseller is a book or other media noted for its top selling status, with bestseller lists published by newspapers, magazines, and book store chains. Some lists are broken down into classifications and specialties (novel, nonfiction book, cookb ...

and has sold more than 25 million copies in 40 languages. It was included on ''Time'''s list of the 100 best nonfiction books since the magazine's founding. Errol Morris made a documentary, '' A Brief History of Time'' (1991) which combines material from Hawking's book with interviews featuring Hawking, his colleagues, and his family.

An illustrated version was published in 1996. In 2006, Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow published an abridged version, ''A Briefer History of Time''.

Publication

In 1983, Hawking approached Simon Mitton, the editor in charge ofastronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

books at Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

, with his ideas for a popular book on cosmology. Mitton was doubtful about all the equations in the draft manuscript, which he felt would put off the buyers in airport bookshops that Hawking wished to reach. In the acknowledgements, Hawking says he was warned that for every equation

In mathematics, an equation is a mathematical formula that expresses the equality of two expressions, by connecting them with the equals sign . The word ''equation'' and its cognates in other languages may have subtly different meanings; for ...

in the book, the readership would be halved. So it includes only a single equation: .

Contents

Chapter 1: Our Picture of the Universe

Hawking begins with an anecdote about a scientist lecturing on the universe. An old woman got up and said, "What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise." The scientist asked what the tortoise was standing on. She replied, "You're very clever young man, very clever. But it's turtles all the way down!" Hawking goes on to explain why we know better.

He discusses the history of

Hawking begins with an anecdote about a scientist lecturing on the universe. An old woman got up and said, "What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise." The scientist asked what the tortoise was standing on. She replied, "You're very clever young man, very clever. But it's turtles all the way down!" Hawking goes on to explain why we know better.

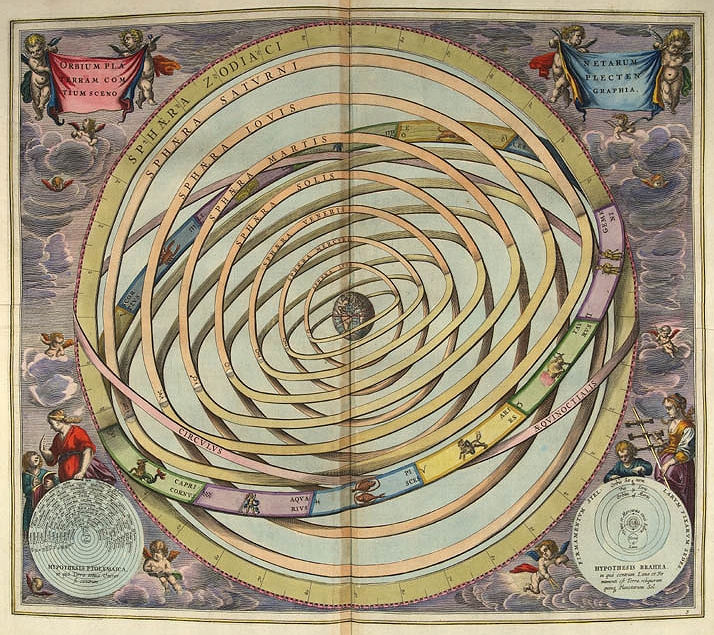

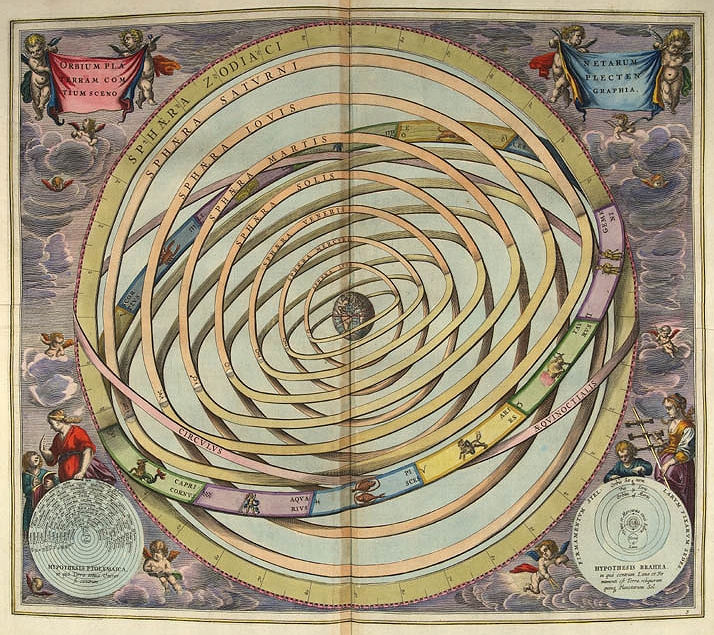

He discusses the history of astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, starting with Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's conclusions about a spherical Earth

Spherical Earth or Earth's curvature refers to the approximation of the figure of the Earth as a sphere. The earliest documented mention of the concept dates from around the 5th century BC, when it appears in the writings of Ancient Greek philos ...

and a circular geocentric model

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded scientific theories, superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric m ...

of the universe, later elaborated upon by the second-century Greek astronomer Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

. He discusses the development of the heliocentric model of the Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

by the Polish astronomer Nicholas Copernicus in 1514. A century later, the Italian Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

turned a Dutch spyglass to the heavens. His observations of Jupiter's moons provided support for Copernicus. The German astronomer Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

formulated his laws of planetary motion, in which planets move in ellipses. Kepler's laws were explained by English physicist Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

in his ''Principia Mathematica

The ''Principia Mathematica'' (often abbreviated ''PM'') is a three-volume work on the foundations of mathematics written by the mathematician–philosophers Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell and published in 1910, 1912, and 1 ...

'' (1687).

Hawking discusses how the subject of the origin of the universe has been debated over time: the perennial existence of the universe hypothesized by Aristotle and other early philosophers was opposed by St. Augustine and other theologians' belief in its creation at a specific time in the past. Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

argued that time had no beginning. In our time, the discovery of the expanding universe implied that between 10 billion and 20 billion years ago, the entire universe was contained in one singular extremely dense place, and that it doesn't make sense to ask what happened before. He writes: "An expanding universe does not preclude a creator, but it does place limits on when he might have carried out his job!"

Chapter 2: Space and Time

Hawking describes the evolution of scientific thought regarding the nature ofspace

Space is a three-dimensional continuum containing positions and directions. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions. Modern physicists usually consider it, with time, to be part of a boundless ...

and time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

. He starts with the Aristotelian idea that the naturally preferred state of a body is to be at rest, and it can only be moved by force

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an Physical object, object to change its velocity unless counterbalanced by other forces. In mechanics, force makes ideas like 'pushing' or 'pulling' mathematically precise. Because the Magnitu ...

, implying that heavier objects will fall faster. However, Galileo experimentally disproved Aristotle's theory by observing the motion of objects of different weights and concluding that all objects would fall at the same rate. This led to Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three physical laws that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws, which provide the basis for Newtonian mechanics, can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body re ...

and gravity. However, Newton's laws implied that there is no such thing as absolute state of rest or absolute space: whether an object is 'at rest' or 'in motion' depends on the observer's inertial frame of reference

In classical physics and special relativity, an inertial frame of reference (also called an inertial space or a Galilean reference frame) is a frame of reference in which objects exhibit inertia: they remain at rest or in uniform motion relative ...

.

Hawking describes the classical belief in absolute time, that observers in motion will measure the same time. However, Hawking writes that this commonsense notion does not work at or near the speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant exactly equal to ). It is exact because, by international agreement, a metre is defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time i ...

. That light travels at a finite speed was discovered by Ole Rømer through his observations of Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

and its moons. Scottish scientist James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

's equations unifying electricity and magnetism predicted the existence of waves moving at a fixed speed, the same speed that had been measured for light. Physicists believed that light must travel through a luminiferous aether

Luminiferous aether or ether (''luminiferous'' meaning 'light-bearing') was the postulated Transmission medium, medium for the propagation of light. It was invoked to explain the ability of the apparently wave-based light to propagate through empt ...

, and that the speed of light was relative to that of the aether. The Michelson–Morley experiment

The Michelson–Morley experiment was an attempt to measure the motion of the Earth relative to the luminiferous aether, a supposed medium permeating space that was thought to be the carrier of light waves. The experiment was performed between ...

, designed to detect the speed of light through the aether, got a null result. Michelson and Morley found that the speed of light was constant regardless of the motion of the source or the observer. In 1905, Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

argued that the aether is superfluous if we abandon absolute time. His special theory of relativity is based on two postulates: the laws of physics are the same for all observers moving relative to one another, and the speed of light is a universal constant.

Remarkable consequences follow. Mass and energy are related by the equation , which means that an infinite amount of energy is needed for any object with mass to travel at the speed of light (c = 3×10⁸m/s). It follows that no material body can travel at or beyond the speed of light. A 4-dimensional spacetime

In physics, spacetime, also called the space-time continuum, is a mathematical model that fuses the three dimensions of space and the one dimension of time into a single four-dimensional continuum. Spacetime diagrams are useful in visualiz ...

is described, in which 'space' and 'time' are intrinsically linked. The motion of an object through space inevitably impacts the way in which it experiences time.

In 1915, Einstein published general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity, and as Einstein's theory of gravity, is the differential geometry, geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of grav ...

, which explains gravity as the curvature of spacetime. Matter and energy (including light) follow geodesics. Einstein's theory of gravity predicts a dynamic universe.

Chapter 3: The Expanding Universe

Hawking describes how physicists and astronomers calculated the relative distance of stars from the Earth. Sir

Hawking describes how physicists and astronomers calculated the relative distance of stars from the Earth. Sir William Herschel

Frederick William Herschel ( ; ; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline Herschel. Born in the Electorate of Hanover ...

confirmed the positions and distances of many stars in the night sky. In 1924, Edwin Hubble

Edwin Powell Hubble (November 20, 1889 – September 28, 1953) was an American astronomer. He played a crucial role in establishing the fields of extragalactic astronomy and observational cosmology.

Hubble proved that many objects previously ...

discovered a method to measure the distance using the brightness

Brightness is an attribute of visual perception in which a source appears to be radiating/reflecting light. In other words, brightness is the perception dictated by the luminance of a visual target. The perception is not linear to luminance, and ...

of Cepheid variable stars as viewed from Earth. The luminosity

Luminosity is an absolute measure of radiated electromagnetic radiation, electromagnetic energy per unit time, and is synonymous with the radiant power emitted by a light-emitting object. In astronomy, luminosity is the total amount of electroma ...

and distance of these stars are related by a simple mathematical formula. Using this, he showed that ours is not the only galaxy.

In 1929, Hubble discovered that light from most galaxies was shifted to the red, and that the degree of redshift is directly proportional to distance. From this, he determined that the universe is expanding. This possibility had not been seriously considered. Einstein was so sure of a static universe that he added the cosmological constant

In cosmology, the cosmological constant (usually denoted by the Greek capital letter lambda: ), alternatively called Einstein's cosmological constant,

is a coefficient that Albert Einstein initially added to his field equations of general rel ...

to his equations. Many astronomers also tried to avoid the implications of general relativity, with one notable exception: the Russian physicist Alexander Friedmann.

In 1922, Friedmann made two very simple assumptions: the universe is identical wherever we are, (homogeneity

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts relating to the Uniformity (chemistry), uniformity of a Chemical substance, substance, process or image. A homogeneous feature is uniform in composition or character (i.e., color, shape, size, weight, ...

), and that it is identical in every direction that we look, (isotropy

In physics and geometry, isotropy () is uniformity in all orientations. Precise definitions depend on the subject area. Exceptions, or inequalities, are frequently indicated by the prefix ' or ', hence ''anisotropy''. ''Anisotropy'' is also u ...

). It follows that the universe is non-static. Support was found when two physicists at Bell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, commonly referred to as ''Bell Labs'', is an American industrial research and development company owned by Finnish technology company Nokia. With headquarters located in Murray Hill, New Jersey, Murray Hill, New Jersey, the compa ...

, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, found unexpected microwave radiation coming from all parts of the sky.

At around the same time, Robert H. Dicke and Jim Peebles were also working on microwave radiation. They argued that radiation from the early universe should be detectable as the cosmic microwave background

The cosmic microwave background (CMB, CMBR), or relic radiation, is microwave radiation that fills all space in the observable universe. With a standard optical telescope, the background space between stars and galaxies is almost completely dar ...

. This was what Penzias and Wilson had found.

In 1965, Roger Penrose

Sir Roger Penrose (born 8 August 1931) is an English mathematician, mathematical physicist, Philosophy of science, philosopher of science and Nobel Prize in Physics, Nobel Laureate in Physics. He is Emeritus Rouse Ball Professor of Mathematics i ...

used general relativity to prove that a collapsing star could result in a singularity. Hawking and Penrose proved together that the universe should have arisen from a singularity. Hawking later argued this need not be the case once quantum effects are taken into account.

Chapter 4: The Uncertainty Principle

Hawking begins by discussing nineteenth-century French mathematicianLaplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

's belief in scientific determinism, where scientific law

Scientific laws or laws of science are statements, based on repeated experiments or observations, that describe or predict a range of natural phenomena. The term ''law'' has diverse usage in many cases (approximate, accurate, broad, or narrow ...

s would be able to perfectly predict the future of the universe. A crack in classical physics appeared with the ultraviolet catastrophe

The ultraviolet catastrophe, also called the Rayleigh–Jeans catastrophe, was the prediction of late 19th century and early 20th century classical physics that an ideal black body at thermal equilibrium would emit an unbounded quantity of en ...

: according to the calculations of British scientists Lord Rayleigh and James Jeans

Sir James Hopwood Jeans (11 September 1877 – 16 September 1946) was an English physicist, mathematician and an astronomer. He served as a secretary of the Royal Society from 1919 to 1929, and was the president of the Royal Astronomical Soci ...

, a hot body should radiate an infinite amount of energy. In 1900, the ultraviolet catastrophe was averted by Max Planck

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck (; ; 23 April 1858 – 4 October 1947) was a German Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist whose discovery of energy quantum, quanta won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.

Planck made many substantial con ...

, who proposed that energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

must be absorbed or emitted in discrete packets called quanta.

Hawking discusses Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg (; ; 5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist, one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics and a principal scientist in the German nuclear program during World War II.

He pub ...

's uncertainty principle

The uncertainty principle, also known as Heisenberg's indeterminacy principle, is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics. It states that there is a limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties, such as position a ...

, according to which the speed and the position of a particle

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscle in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

cannot be precisely known due to Planck's quantum hypothesis: increasing the accuracy in measuring its speed will decrease the certainty of its position and vice versa. This overturned Laplace's idea of a completely deterministic theory of the universe. Hawking describes the development by Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger

Erwin Rudolf Josef Alexander Schrödinger ( ; ; 12 August 1887 – 4 January 1961), sometimes written as or , was an Austrian-Irish theoretical physicist who developed fundamental results in quantum field theory, quantum theory. In particul ...

and Paul Dirac

Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac ( ; 8 August 1902 – 20 October 1984) was an English mathematician and Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who is considered to be one of the founders of quantum mechanics. Dirac laid the foundations for bot ...

of quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

, a theory which introduced an irreducible element of unpredictability into science, and despite Einstein's strong objections, has proven to be very successful in describing the universe at small scales.

Hawking discusses how Heisenberg's uncertainty principle implies the

Hawking discusses how Heisenberg's uncertainty principle implies the wave–particle duality

Wave–particle duality is the concept in quantum mechanics that fundamental entities of the universe, like photons and electrons, exhibit particle or wave (physics), wave properties according to the experimental circumstances. It expresses the in ...

of light (and particles in general).  He describes the phenomenon of

He describes the phenomenon of interference

Interference is the act of interfering, invading, or poaching. Interference may also refer to:

Communications

* Interference (communication), anything which alters, modifies, or disrupts a message

* Adjacent-channel interference, caused by extra ...

, where multiple light waves interfere with each other to give rise to a single light wave with properties different from those of the component waves, as well as the interference within particles, exemplified by the two-slit experiment. Hawking writes that American scientist Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of t ...

's sum over histories is a useful way of visualize quantum behavior. Hawking explains that Einstein's general theory of relativity is a classical, non-quantum theory as it ignores the uncertainty principle and that it has to be reconciled with quantum theory in situations where gravity is very strong, as in a singularity.

Chapter 5: Elementary Particles and Forces of Nature

Hawking traces the history of investigation into the nature ofmatter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic pa ...

: Aristotle's four elements, Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

's indivisible atoms

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished from each other ...

, John Dalton

John Dalton (; 5 or 6 September 1766 – 27 July 1844) was an English chemist, physicist and meteorologist. He introduced the atomic theory into chemistry. He also researched Color blindness, colour blindness; as a result, the umbrella term ...

's idea of atoms combining to form molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

s, J. J. Thomson's discovery of the electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

, Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both Atomic physics, atomic and nuclear physics. He has been described as "the father of nu ...

's discovery of the atomic nucleus

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford at the Department_of_Physics_and_Astronomy,_University_of_Manchester , University of Manchester ...

, James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English nuclear physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1935 for his discovery of the neutron. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspired t ...

's discovery of the neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The Discovery of the neutron, neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nucle ...

and finally Murray Gell-Mann

Murray Gell-Mann (; September 15, 1929 – May 24, 2019) was an American theoretical physicist who played a preeminent role in the development of the theory of elementary particles. Gell-Mann introduced the concept of quarks as the funda ...

's theorizing of quark

A quark () is a type of elementary particle and a fundamental constituent of matter. Quarks combine to form composite particles called hadrons, the most stable of which are protons and neutrons, the components of atomic nucleus, atomic nuclei ...

s which constitute protons and neutrons (collectively called hadrons

In particle physics, a hadron is a composite subatomic particle made of two or more quarks held together by the strong nuclear force. Pronounced , the name is derived . They are analogous to molecules, which are held together by the electric ...

). Hawking discusses the six different "flavors" ( up, down, strange, charm, bottom, and top

Top most commonly refers to:

* Top, a basic term of orientation, distinguished from bottom, front, back, and sides

* Spinning top, a ubiquitous traditional toy

* Top (clothing), clothing designed to be worn over the torso

* Mountain top, a moun ...

) and three different "colors

Color (or colour in Commonwealth English; see spelling differences) is the visual perception based on the electromagnetic spectrum. Though color is not an inherent property of matter, color perception is related to an object's light absorpt ...

" of quarks (red, green, and blue). Later he discusses anti-quarks, which are outnumbered by quarks due to the expansion and cooling of the universe.

Wolfgang Pauli

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli ( ; ; 25 April 1900 – 15 December 1958) was an Austrian theoretical physicist and a pioneer of quantum mechanics. In 1945, after having been nominated by Albert Einstein, Pauli received the Nobel Prize in Physics "for the ...

's exclusion principle: they cannot share the same quantum state

In quantum physics, a quantum state is a mathematical entity that embodies the knowledge of a quantum system. Quantum mechanics specifies the construction, evolution, and measurement of a quantum state. The result is a prediction for the system ...

(for example, two "spin up" protons cannot occupy the same location in space). Without this rule, atoms could not exist. Bosons

In particle physics, a boson ( ) is a subatomic particle whose spin quantum number has an integer value (0, 1, 2, ...). Bosons form one of the two fundamental classes of subatomic particle, the other being fermions, which have half odd-integer ...

, or the force-carrying particles, have a spin of 0, 1, or 2 and do not follow the exclusion principle.

electromagnetic force

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. It is the dominant force in the interac ...

is carried by photons

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless particles that ...

. The weak nuclear force is responsible for radioactivity

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is conside ...

and is carried by W and Z bosons

In particle physics, the W and Z bosons are vector bosons that are together known as the weak bosons or more generally as the intermediate vector bosons. These elementary particles mediate the weak interaction; the respective symbols are , , an ...

. The strong nuclear force, which binds quarks into hadrons and binds hadrons together into atomic nuclei, is carried by the gluon

A gluon ( ) is a type of Massless particle, massless elementary particle that mediates the strong interaction between quarks, acting as the exchange particle for the interaction. Gluons are massless vector bosons, thereby having a Spin (physi ...

. Hawking writes that color confinement

In quantum chromodynamics (QCD), color confinement, often simply called confinement, is the phenomenon that color-charged particles (such as quarks and gluons) cannot be isolated, and therefore cannot be directly observed in normal conditions b ...

prevents the discovery of quarks and gluons on their own (except at extremely high temperature) as they remain confined within hadrons.

Hawking writes that at extremely high temperature, the electromagnetic force and weak nuclear force behave as a single electroweak force, giving rise to the speculation that at even higher temperatures, the electroweak force and strong nuclear force would also behave as a single force. Theories which attempt to describe the behaviour of this "combined" force are called Grand Unified Theories, which may help us explain many of the mysteries of physics.

Chapter 6: Black Holes

Hawking discusses

Hawking discusses black hole

A black hole is a massive, compact astronomical object so dense that its gravity prevents anything from escaping, even light. Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass will form a black hole. Th ...

s, regions of spacetime

In physics, spacetime, also called the space-time continuum, is a mathematical model that fuses the three dimensions of space and the one dimension of time into a single four-dimensional continuum. Spacetime diagrams are useful in visualiz ...

where extremely strong gravity prevents everything, including light, from escaping them. The term black hole was coined by John Archibald Wheeler

John Archibald Wheeler (July 9, 1911April 13, 2008) was an American theoretical physicist. He was largely responsible for reviving interest in general relativity in the United States after World War II. Wheeler also worked with Niels Bohr to e ...

in 1969, although the idea is older. The Cambridge clergyman John Michell

John Michell (; 25 December 1724 – 21 April 1793) was an English natural philosopher and clergyman who provided pioneering insights into a wide range of scientific fields including astronomy, geology, optics, and gravitation. Considered "on ...

imagined stars so massive that light could not escape their gravitational pull. Hawking explains stellar evolution

Stellar evolution is the process by which a star changes over the course of time. Depending on the mass of the star, its lifetime can range from a few million years for the most massive to trillions of years for the least massive, which is consi ...

: how main sequence stars shine by fusing hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

into helium

Helium (from ) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, non-toxic, inert gas, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. Its boiling point is ...

, staving off gravitational collapse. A collapsed star may form a white dwarf

A white dwarf is a Compact star, stellar core remnant composed mostly of electron-degenerate matter. A white dwarf is very density, dense: in an Earth sized volume, it packs a mass that is comparable to the Sun. No nuclear fusion takes place i ...

, supported by electron degeneracy, or a neutron star

A neutron star is the gravitationally collapsed Stellar core, core of a massive supergiant star. It results from the supernova explosion of a stellar evolution#Massive star, massive star—combined with gravitational collapse—that compresses ...

, supported by the exclusion principle. Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (; 19 October 1910 – 21 August 1995) was an Indian Americans, Indian-American theoretical physicist who made significant contributions to the scientific knowledge about the structure of stars, stellar evolution and ...

found that for a collapsed star of more than 1.4 solar masses, there would be nothing to halt complete gravitational collapse. He was dissuaded from this thinking by Arthur Eddington, though it later won him the Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

. The critical mass is known as the Chandrasekhar limit.

He describes the event horizon

In astrophysics, an event horizon is a boundary beyond which events cannot affect an outside observer. Wolfgang Rindler coined the term in the 1950s.

In 1784, John Michell proposed that gravity can be strong enough in the vicinity of massive c ...

, the black hole's boundary from which no particle can escape. He writes: "One could well say of the event horizon what the poet Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

said of the entrance to Hell: 'All hope abandon, ye who enter here.'" Hawking discusses non-rotating black holes with spherical symmetry

In geometry, circular symmetry is a type of continuous symmetry for a planar object that can be rotated by any arbitrary angle and map onto itself.

Rotational circular symmetry is isomorphic with the circle group in the complex plane, or the ...

and rotating ones with axisymmetry. The discovery of quasars

A quasar ( ) is an extremely Luminosity, luminous active galactic nucleus (AGN). It is sometimes known as a quasi-stellar object, abbreviated QSO. The emission from an AGN is powered by accretion onto a supermassive black hole with a mass rangi ...

by Maarten Schmidt in 1963 and pulsars by Jocelyn Bell-Burnell in 1967 gave hope that black holes might be detected. Even though black holes (by definition) do not emit light, astronomers can observe them through their interactions with visible matter. A star falling into a black hole would be a powerful source of X-rays

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

. Cygnus X-1, a powerful source of X-rays, was the earliest plausible candidate for a black hole. Hawking concludes by mentioning his 1974 bet with American physicist Kip Thorne. Hawking argued that Cygnus X-1 does not contain a black hole. Hawking conceded the bet as evidence for black holes proved overwhelming.

Chapter 7: Black Holes Ain't So Black

Hawking discusses an aspect of black holes' behavior that he discovered in the 1970s. According to earlier theories, black holes can only become larger because nothing which enters a black hole can come out. This was similar toentropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, most commonly associated with states of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynamics, where it was first recognized, to the micros ...

, a measure of disorder which, per the second law of thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law based on Universal (metaphysics), universal empirical observation concerning heat and Energy transformation, energy interconversions. A simple statement of the law is that heat always flows spont ...

, always increases. Hawking and his student Jacob Bekenstein suggested that the area of a black hole's event horizon is a measure of its entropy.

But if a black hole has entropy, it must have a temperature, and must emit radiation. In 1974, Hawking published a new theory which argued that black holes can emit radiation. He imagined what might happen if a pair of virtual particles

A virtual particle is a theoretical transient particle that exhibits some of the characteristics of an ordinary particle, while having its existence limited by the uncertainty principle, which allows the virtual particles to spontaneously emer ...

appeared near the edge of a black hole. Virtual particles briefly 'borrow' energy from the vacuum, then annihilate each other, returning the borrowed energy and ceasing to exist. However, at the edge of a black hole, one virtual particle might be trapped by the black hole while the other escapes. Thus, the particle takes energy from the black hole instead of from the vacuum, and escape from the black hole as Hawking radiation

Hawking radiation is black-body radiation released outside a black hole's event horizon due to quantum effects according to a model developed by Stephen Hawking in 1974.

The radiation was not predicted by previous models which assumed that onc ...

. According to Hawking, black holes must very slowly shrink over time and eventually "evaporate" because of this radiation.

Chapter 8: The Origin and Fate of the Universe

Hawking recalls a conference on cosmology at the Vatican, where he was given an audience with

Hawking recalls a conference on cosmology at the Vatican, where he was given an audience with Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

. The Pope said it was fine to study the early universe, but scientists should not study the Big Bang itself, as that was the moment of Creation and the work of God. Hawking writes: "I was glad then that he did not know the subject of the talk I had just given at the conference -- the possibility that space-time was finite but had no boundary, which means that it had no beginning, no moment of Creation. I had no desire to share the fate of Galileo, with whom I feel a strong sense of identity, partly because of the coincidence of having been born exactly 300 years after his death!"

At the Big Bang, the universe had an extremely high temperature, which prevented the formation of complex structures like stars, or even very simple ones like atoms. George Gamow predicted that radiation from the Big Bang should still fill the present universe. This was the cosmic microwave background discovered by Penzias and Wilson. The Big Bang created hydrogen and helium, and heavier elements were forged in stars.

The Big Bang model was supported by the redshift of galaxies, the cosmic microwave background and the relative abundance of hydrogen and helium. But mysteries remained: Why is the universe isotropic? Why is the cosmic microwave background so homogenous? Widely separated parts of the universe have the same temperature, but there would not have been time for these regions to have come into contact. Alan Guth's model of cosmic Inflation provided an answer to this horizon problem. Inflation explains other characteristics of the universe that had previously greatly confused researchers. After inflation, the universe continued to expand at a slower pace. It became much colder, eventually allowing for the formation of such stars.

Hawking discusses how the universe might have appeared if it had expanded slower or faster than it actually has. If the universe expanded too slowly, it would collapse, and there would not be enough time for life to form. If the universe expanded too quickly, it would have become almost empty. He discusses the anthropic principle

In cosmology, the anthropic principle, also known as the observation selection effect, is the proposition that the range of possible observations that could be made about the universe is limited by the fact that observations are only possible in ...

, which states that the universe has laws of physics that allow for the evolution of life because, if it didn't, we wouldn't be here.

Hawking suggests the no boundary proposal: that the universe is finite but has no beginning in imaginary time. It might merely exist.

Chapter 9: The Arrow of Time

Hawking discusses three " arrows of time". The first is the thermodynamic arrow of time: the direction in which entropy increases. This is given as the explanation for why we never see the broken pieces of a cup gather themselves together to form a whole cup. The second is the psychological arrow of time, whereby our subjective sense of time seems to flow in one direction, which is why we remember the past and not the future. The third is the cosmological arrow of time: the direction in which the universe is expanding rather than contracting. Hawking claims that the psychological arrow is intertwined with the thermodynamic arrow. According to Hawking, during a contraction phase of the universe, the thermodynamic and cosmological arrows of time would not agree. Hawking then claims that the "no boundary proposal" for the universe implies that the universe will expand for some time before contracting back again. He goes on to argue that the no boundary proposal is what drives entropy and that it predicts the existence of a well-defined thermodynamic arrow of time if and only if the universe is expanding, as it implies that the universe must have started in a smooth and ordered state that must grow toward disorder as time advances. He argues that, because of the no boundary proposal, a contracting universe would not have a well-defined thermodynamic arrow and therefore only a universe that is in an expansion phase can support intelligent life. Using the weak anthropic principle, Hawking goes on to argue that the thermodynamic arrow must agree with the cosmological arrow in order for either to be observed by intelligent life. This, in Hawking's view, is why humans experience these three arrows of time going in the same direction.Chapter 10: Wormholes and Time Travel

Hawking discusses whethertime travel

Time travel is the hypothetical activity of traveling into the past or future. Time travel is a concept in philosophy and fiction, particularly science fiction. In fiction, time travel is typically achieved through the use of a device known a ...

is possible. He shows how physicists have attempted to devise possible methods by humans with advanced technology may be able to travel faster than the speed of light, or travel backwards in time. Kurt Gödel

Kurt Friedrich Gödel ( ; ; April 28, 1906 – January 14, 1978) was a logician, mathematician, and philosopher. Considered along with Aristotle and Gottlob Frege to be one of the most significant logicians in history, Gödel profoundly ...

presented Einstein with a solution to general relativity that allowed for time travel in a rotating universe. Einstein–Rosen bridges were proposed early in the history of the theory. These wormholes would appear identical to black holes from the outside, but matter which entered would be relocated to a different location in spacetime, potentially in a distant region of space, or even backwards in time. However, later research demonstrated that such a wormhole would not allow any material to pass through before turning back into a regular black hole. The only way that a wormhole could theoretically remain open, and thus allow faster-than-light travel or time travel, would require the existence of exotic matter

There are several proposed types of exotic matter:

* Hypothetical particles and states of matter that have not yet been encountered, but whose properties would be within the realm of mainstream physics if found to exist.

* Several particles who ...

with negative energy density

In physics, energy density is the quotient between the amount of energy stored in a given system or contained in a given region of space and the volume of the system or region considered. Often only the ''useful'' or extractable energy is measure ...

, which violates the energy conditions of general relativity. As such, almost all physicists agree that faster-than-light travel and travel backwards in time are not possible.

Chapter 11: The Unification of Physics

Quantum mechanics and general relativity describe the universe with astounding accuracy within their own domains of applicability (atomic and cosmic scales, respectively). However, these two theories run into problems when combined. For example, the uncertainty principle is incompatible with Einstein's theory. This contradiction has led physicists to search for a theory ofquantum gravity

Quantum gravity (QG) is a field of theoretical physics that seeks to describe gravity according to the principles of quantum mechanics. It deals with environments in which neither gravitational nor quantum effects can be ignored, such as in the v ...

.

Hawking is cautiously optimistic that such a unified theory of the universe may be found soon, in spite of significant challenges. At the time the book was written, superstring theory

Superstring theory is an attempt to explain all of the particles and fundamental forces of nature in one theory by modeling them as vibrations of tiny supersymmetric strings.

'Superstring theory' is a shorthand for supersymmetric string t ...

had emerged as the most popular theory of quantum gravity, but this theory and related string theories were still incomplete and had not yielded testable predictions (this remains the case as of 2021). String theory proposes that particles behave like one-dimensional "strings", rather than as dimensionless particles. These strings "vibrate" in many dimensions. Superstring theory requires a total of 10 dimensions. The nature of the six "hyperspace" dimensions required by superstring theory are difficult if not impossible to study.

Hawking thus proposes three possibilities: 1) there exists a complete unified theory that we will eventually find; 2) the overlapping characteristics of different landscapes will allow us to gradually explain physics more accurately with time and 3) there is no ultimate theory. The third possibility has been sidestepped by acknowledging the limits set by the uncertainty principle. The second possibility describes what has been happening in physical sciences so far, with increasingly accurate partial theories.

Hawking believes that such refinement has a limit and that by studying the very early stages of the universe in a laboratory setting, a complete theory of Quantum Gravity will be found in the 21st century allowing physicists to solve many of the currently unsolved problems in physics.

Conclusion

Hawking summarises the efforts made by humans through their history to understand the universe and their place in it: starting from the belief in anthropomorphic spirits controlling nature, followed by the recognition of regular patterns in nature, and finally with the understanding of the inner workings of the universe. He recalls Laplace's suggestion that the universe's structure and evolution could eventually be precisely explained by a set of laws whose origin is left in God's domain. However, Hawking states that the uncertainty principle introduced by quantum theory has set limits on knowledge. Hawking comments that historically, the study of cosmology has been primarily motivated by a search for philosophical and religious insights, for instance, to better understand the nature of God, or even whether God exists at all. However, for Hawking, most scientists today who work on these theories approach them with mathematical calculation and empirical observation, rather than asking such philosophical questions. In his mind, the increasingly technical nature of these theories have caused modern cosmology to become increasingly divorced from philosophy. Hawking nonetheless expresses hope that one day everybody would understand the true origin and nature of the universe. "That would be the ultimate triumph of human reason—for then we know would know the mind of God".Editions

* 1988: The first edition included an introduction byCarl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is his research on the possibility of extraterrestrial life, including e ...

that tells the following story: Sagan was in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

for a scientific conference in 1974, and between sessions he wandered into a different room, where a larger meeting was taking place. "I realized that I was watching an ancient ceremony: the investiture of new fellows into the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, one of the most ancient scholarly organizations on the planet. In the front row, a young man in a wheelchair was, very slowly, signing his name in a book that bore on its earliest pages the signature of Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

... Stephen Hawking was a legend even then." In his introduction, Sagan goes on to add that Hawking is the "worthy successor" to Newton and Paul Dirac

Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac ( ; 8 August 1902 – 20 October 1984) was an English mathematician and Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who is considered to be one of the founders of quantum mechanics. Dirac laid the foundations for bot ...

, both former Lucasian Professors of Mathematics.

The introduction was removed after the first edition, as it was copyright

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive legal right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, ...

ed by Sagan, rather than by Hawking or the publisher, and the publisher did not have the right to reprint it in perpetuity. Hawking wrote his own introduction for later editions.

* 1994, A brief history of time – An interactive adventure. A CD-Rom with interactive video material created by S. W. Hawking, Jim Mervis, and Robit Hairman (available for Windows 95, Windows 98, Windows ME, and Windows XP).

* 1996, Illustrated, updated and expanded edition: This hardcover edition contained full-color illustrations and photographs to help further explain the text, as well as the addition of topics that were not included in the original book.

* 1998, Tenth-anniversary edition: It features the same text as the one published in 1996, but was also released in paperback and has only a few diagrams included.

* 2005, '' A Briefer History of Time'': a collaboration with Leonard Mlodinow of an abridged version of the original book. It was updated again to address new issues that had arisen due to further scientific development.

Film

In 1991, Errol Morris directed adocumentary film

A documentary film (often described simply as a documentary) is a nonfiction Film, motion picture intended to "document reality, primarily for instruction, education or maintaining a Recorded history, historical record". The American author and ...

about Hawking; although they share a title, the film is a biographical study of Hawking, and not a filmed version of the book.

Apps

"Stephen Hawking's Pocket Universe: A Brief History of Time Revisited" is based on the book. The app was developed by Preloaded for Transworld publishers, a division of thePenguin Random House

Penguin Random House Limited is a British-American multinational corporation, multinational conglomerate (company), conglomerate publishing company formed on July 1, 2013, with the merger of Penguin Books and Random House. Penguin Books was or ...

group.

The app was produced in 2016. It was designed by Ben Courtney and produced by Jemma Harris and is available on iOS

Ios, Io or Nio (, ; ; locally Nios, Νιός) is a Greek island in the Cyclades group in the Aegean Sea. Ios is a hilly island with cliffs down to the sea on most sides. It is situated halfway between Naxos and Santorini. It is about long an ...

only.

Opera

TheMetropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera is an American opera company based in New York City, currently resident at the Metropolitan Opera House (Lincoln Center), Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Referred ...

commissioned an opera to premiere in the 2015–2016 season based on Hawking's book. It was to be composed by Osvaldo Golijov with a libretto by Alberto Manguel

Alberto Manguel (born March 13, 1948, in Buenos Aires) is an Argentine Canadian, Argentine-Canadian anthologist, translator, essayist, novelist, editor, and a former director of the National Library of Argentina. He is a cosmopolitan and polyglo ...

in a production by Robert Lepage

Robert Lepage (born December 12, 1957) is a Canadian playwright, actor, film director, and stage director.

Early life

Lepage was raised in Quebec City. At age five, he was diagnosed with a rare form of alopecia, which caused complete hair lo ...

. The planned opera was changed to be about a different subject and eventually canceled completely.

Reception

''A Brief History of Time'' was included on ''Time'' magazine's list of the 100 best nonfiction books since the magazine's founding. Jeffrey Kluger wrote:The genius of Hawking was to understand that while people weren’t losing much sleep over such matters as event horizons, space-time geodesics and stellar contraction, they were deeply, primally interested in such questions as “Why does the universe go to all the bother of existing?” as he elegantly put it. In that riddle lives the smaller but more anthropocentrically relevant one, Why do we exist? Hawking provided answers — with hard physics, gentle metaphor, and ideas so big they fill up space itself. And you know what? We got it — and we’re smarter and better because of that.

See also

* * Hawking Index – a mock mathematical measurement of how far people will read a book before giving up, named in reference to Hawking's book. * List of textbooks in thermodynamics and statistical mechanics * List of textbooks on classical mechanics and quantum mechanics * Turtles all the way down – a jocular expression of theinfinite regress

Infinite regress is a philosophical concept to describe a series of entities. Each entity in the series depends on its predecessor, following a recursive principle. For example, the epistemic regress is a series of beliefs in which the justi ...

problem in cosmology that appears in Hawking's book

* '' The Road to Reality'' (2004), a guide to physics by Roger Penrose

Sir Roger Penrose (born 8 August 1931) is an English mathematician, mathematical physicist, Philosophy of science, philosopher of science and Nobel Prize in Physics, Nobel Laureate in Physics. He is Emeritus Rouse Ball Professor of Mathematics i ...

References

External links

Photos of the first edition of ''A Brief History of Time''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Brief History Of Time, A 1988 non-fiction books Books by Stephen Hawking English-language non-fiction books Popular physics books Cosmology books Bantam Books books