A. V. Dicey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

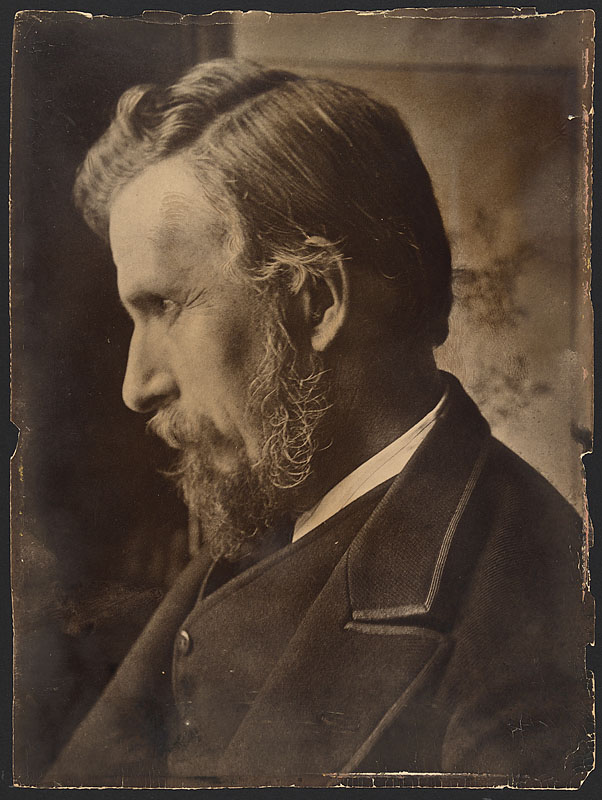

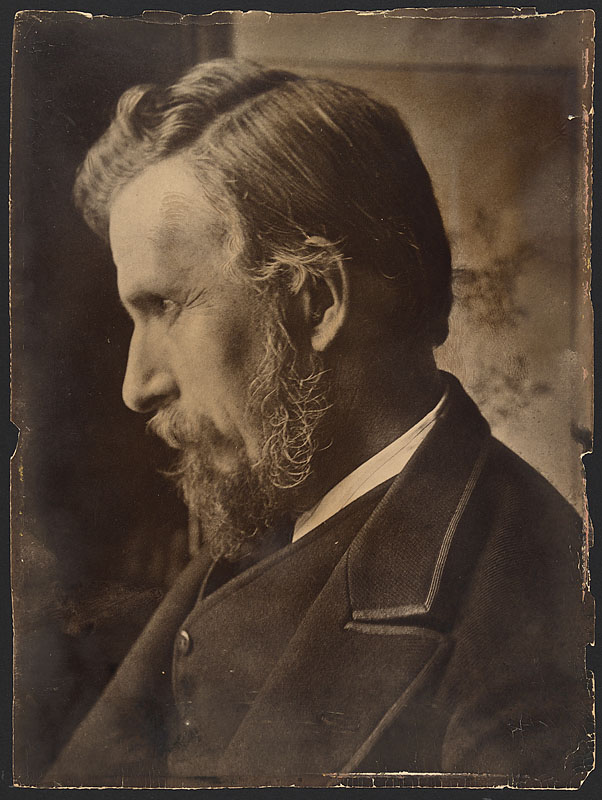

Albert Venn Dicey, (4 February 1835 – 7 April 1922) was a British Whig

Dicey was receptive to

Dicey was receptive to

''A digest of the law of England with reference to the conflict of laws''

(1st ed. 1896, 2nd ed. 1908); ** later expanded in various editions of Dicey Morris & Collins * * ''A Fool's Paradise: Being a Constitutionalist's Criticism of the Home Rule Bill of 1912'' (1913) * * * * * Vol. 1 includes the first edition of ''Introduction'', with the main addenda in later editions; vol. 2, ''The Comparative Study of Constitutions'', provides largely unpublished lectures on comparative constitutional law, intended for a further book; both volumes have extensive editorial commentary.

Grave of Albert Venn Dicey and his wife Eleanor in St Sepulchre's Cemetery, Oxford, with biographyGreat Thinkers: Vernon Bogdanor FBA on A.V. Dicey FBA

podcast, The British Academy * {{DEFAULTSORT:Dicey, A. V. 1835 births 1922 deaths Academics of the London School of Economics Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford Scholars of constitutional law English constitutionalists English legal scholars English legal writers Conflict of laws scholars People educated at King's College School, London Vinerian Professors of English Law English King's Counsel Members of the Inner Temple Fellows of Trinity College, Oxford Fellows of the British Academy Presidents of the Oxford Union People from Lutterworth Burials at St Sepulchre's Cemetery

jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyzes and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal education in law (a law degree) and often a Lawyer, legal prac ...

and constitutional theorist. He is most widely known as the author of '' Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution'' (1885). The principles it expounds are considered part of the uncodified British constitution. He became Vinerian Professor of English Law at Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, one of the first Professors of Law at the LSE Law School

A law school (also known as a law centre/center, college of law, or faculty of law) is an institution, professional school, or department of a college or university specializing in legal education, usually involved as part of a process for b ...

, and a leading constitutional scholar of his day. Dicey popularised the phrase "rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

", although its use goes back to the 17th century.

Biography

Dicey was born on 4 February 1835. His father was Thomas Edward Dicey, senior wrangler in 1811 and proprietor of the '' Northampton Mercury'' and Chairman of theMidland Railway

The Midland Railway (MR) was a railway company in the United Kingdom from 1844 in rail transport, 1844. The Midland was one of the largest railway companies in Britain in the early 20th century, and the largest employer in Derby, where it had ...

. His mother was Annie Marie Stephen, daughter of James Stephen, Master in Chancery. Per his own words, Dicey owed everything to the wisdom and firmness of his mother. His elder brother was Edward James Stephen Dicey. He was also a cousin of Leslie Stephen and Sir James Fitzjames Stephen.

Dicey was educated at King's College School in London and Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1263 by nobleman John I de Balliol, it has a claim to be the oldest college in Oxford and the English-speaking world.

With a governing body of a master and aro ...

, graduating with Firsts in classical moderations in 1856 and in '' literae humaniores'' in 1858. In 1860 he won a fellowship at Trinity College, Oxford, which he forfeited upon his marriage in 1872.

He was called to the bar by the Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional association for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practice as a barrister in England and Wa ...

in 1863, subscribed to the Jamaica Committee around 1865, and was appointed to the Vinerian Chair of English Law

English law is the common law list of national legal systems, legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly English criminal law, criminal law and Civil law (common law), civil law, each branch having its own Courts of England and Wales, ...

at Oxford in 1882, a post he held until 1909. In his first major work, the seminal ''Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution'', he outlined the principles of parliamentary sovereignty for which he is most known. He argued that the British Parliament was "an absolutely sovereign legislature" with the "right to make or unmake any law". In the book, he defined the term ''constitutional law

Constitutional law is a body of law which defines the role, powers, and structure of different entities within a state, namely, the executive, the parliament or legislature, and the judiciary; as well as the basic rights of citizens and, in ...

'' as including "all rules which directly or indirectly affect the distribution or the exercise of the sovereign power in the state". He understood that the freedom British subjects enjoyed was dependent on the sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

of Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, the impartiality of the courts free from governmental interference and the supremacy of the common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

. In 1890, he was appointed Queen's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

.

He later left Oxford and went on to become one of the first Professors of Law at the then-new London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), established in 1895, is a public research university in London, England, and a member institution of the University of London. The school specialises in the social sciences. Founded ...

. There he published in 1896 his ''Conflict of Laws''. Upon his death on 7 April 1922, Harold Laski memorialised him as "the most considerable figure in English jurisprudence since Maitland."

Political views

Dicey was receptive to

Dicey was receptive to Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February Dual dating, 1747/8 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S.– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of mo ...

's brand of individualist liberalism and welcomed the extension of the franchise in 1867. He was affiliated with the group known as the "University Liberals", who composed the ''Essays on Reform'' and was not ashamed to be labeled a Radical. Dicey held that "personal liberty is the basis of national welfare." He treated Parliamentary sovereignty as the central premise of the British constitution.

A member of the Liberal Unionist Party, Dicey was a strong opponent of the Irish Home Rule movement

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to ...

, writing and speaking against it extensively from 1886 until shortly before his death, advocating that no concessions be made to Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cult ...

in relation to the government of any part of Ireland as an integral part of the United Kingdom. In March 1914 Dicey stated that if a Home Rule Bill was passed it "would be a political crime lacking all moral and constitutional authority...the voice of the present House of Commons was not the voice of the nation." He was thus bitterly disillusioned by the Anglo-Irish Treaty agreement in 1921 that Southern Ireland should become a self-governing dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

(the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

), separate from the United Kingdom.

Dicey was also vehemently opposed to women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

, proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to any electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to political divisions (Political party, political parties) amon ...

(while acknowledging that the existing first-past-the-post system was not perfect), and to the notion that citizens have the right to ignore unjust laws. Dicey viewed the necessity of establishing a stable legal system

A legal system is a set of legal norms and institutions and processes by which those norms are applied, often within a particular jurisdiction or community. It may also be referred to as a legal order. The comparative study of legal systems is th ...

as more important than the potential injustice that would occur from following unjust laws. In spite of this, he did concede that there were circumstances in which it would be appropriate to resort to an armed rebellion but stated that such occasions are extremely rare.

Bibliography

* ''Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution'' (8th Edition with new Introduction) (1915) * ''A Leap in the Dark, or Our New Constitution'' (an examination of the leading principles of the Home Rule Bill of 1893) (1893) * ''A Treatise on the Rules for the Selection of the Parties to an Action'' (1870) * ''England's Case against Home Rule'' (1887) * ''The Privy Council: The Arnold Prize Essay'' (1887) * ''Letters on unionist delusions'' (1887)''A digest of the law of England with reference to the conflict of laws''

(1st ed. 1896, 2nd ed. 1908); ** later expanded in various editions of Dicey Morris & Collins * * ''A Fool's Paradise: Being a Constitutionalist's Criticism of the Home Rule Bill of 1912'' (1913) * * * * * Vol. 1 includes the first edition of ''Introduction'', with the main addenda in later editions; vol. 2, ''The Comparative Study of Constitutions'', provides largely unpublished lectures on comparative constitutional law, intended for a further book; both volumes have extensive editorial commentary.

Biographies

* * *References

External links

* * * * * *Grave of Albert Venn Dicey and his wife Eleanor in St Sepulchre's Cemetery, Oxford, with biography

podcast, The British Academy * {{DEFAULTSORT:Dicey, A. V. 1835 births 1922 deaths Academics of the London School of Economics Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford Scholars of constitutional law English constitutionalists English legal scholars English legal writers Conflict of laws scholars People educated at King's College School, London Vinerian Professors of English Law English King's Counsel Members of the Inner Temple Fellows of Trinity College, Oxford Fellows of the British Academy Presidents of the Oxford Union People from Lutterworth Burials at St Sepulchre's Cemetery