A. M. Azahari on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sheikh Ahmad M. Azahari bin Sheikh Mahmud (28 August 1928 – 30 May 2002), better known as A. M. Azahari, was a Bruneian politician, businessman and nationalist of Arab descent who fought against Dutch colonialism in the

The PRB saw the Constitution as a setback to their hopes, viewing it as a tool of colonialism that gave Brunei self-rule instead of self-administration. The PRB felt that the Constitution will only help a select few Bruneians and the British, rendering the party powerless and confined to press release protests. In spite of this, he accepted the Sultan's nomination to the temporary Legislative Council out of respect to him. His resolution for his Kalimantan Utara plan was defeated after he took office on 16 April 1958. This prompted him to denounce the council as undemocratic and a colonial relic that may push people toward

The PRB saw the Constitution as a setback to their hopes, viewing it as a tool of colonialism that gave Brunei self-rule instead of self-administration. The PRB felt that the Constitution will only help a select few Bruneians and the British, rendering the party powerless and confined to press release protests. In spite of this, he accepted the Sultan's nomination to the temporary Legislative Council out of respect to him. His resolution for his Kalimantan Utara plan was defeated after he took office on 16 April 1958. This prompted him to denounce the council as undemocratic and a colonial relic that may push people toward  To keep the PRB together, Azahari responded to the various goals of his supporters, with the backing of the together ''Barisan Buruh Bersatu Brunei'' (4B), which promised to support the PRB's initiatives. Tensions increased as the party stepped up its verbal assaults on the administration. To aid in the establishment of a state in North Kalimantan, the PRB started a joint campaign in the middle of June 1961 and established the TNKU. To keep the PRB together, he appealed to the various goals of his supporters, with the backing of the together 4B.

Given his socialist leanings, Azahari was able to establish contact with

To keep the PRB together, Azahari responded to the various goals of his supporters, with the backing of the together ''Barisan Buruh Bersatu Brunei'' (4B), which promised to support the PRB's initiatives. Tensions increased as the party stepped up its verbal assaults on the administration. To aid in the establishment of a state in North Kalimantan, the PRB started a joint campaign in the middle of June 1961 and established the TNKU. To keep the PRB together, he appealed to the various goals of his supporters, with the backing of the together 4B.

Given his socialist leanings, Azahari was able to establish contact with

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

, the chairman of the Parti Rakyat Brunei

Brunei People's Party (BPR), also known as (PRB), was a political party in Brunei, now believed to be defunct. It won Brunei’s council elections in 1962 but disputes soon after led to a failed revolt. The party continued in exile for a few ...

(Brunei People's Party) from 1947 to 1962, and the Prime Minister of the North Borneo Federation

The North Borneo Federation, also known as North Kalimantan (), was a proposed political entity which would have comprised the British colonies of Sarawak, British North Borneo (now known as the Malaysian state of Sabah) and the protectorate o ...

in 1962.

Having trained under the Japanese, Azahari elevated Brunei's political opposition to colonialism to unprecedented levels. After serving as an anti-colonialist

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholars of decolon ...

soldier in Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

, he returned in 1952 and became the catalyst for the Brunei revolt

The Brunei revolt () or the Brunei rebellion of 1962 was a December 1962 insurrection in the British protectorate of Brunei by opponents of its monarchy's proposed inclusion in the Federation of Malaysia. The insurgents were members of the ...

against British colonial interests. During the 20th century, he was arguably the most charismatic politician in Brunei. He was an instrument of Indonesian imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

and is known to have publicly opposed Brunei's admission into the Federation of Malaysia

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia. Featuring the Tanjung Piai, southernmost point of continental Eurasia, it is a federation, federal constitutional monarchy consisting of States and federal territories of Malaysia, 13 states and thre ...

.

Early life and education

A. M. Azahari, also known as Sheikh Ahmad M. Azahari bin Sheikh Mahmud, was born in theCrown Colony of Labuan

The Crown Colony of Labuan was a Crown colony off the northwestern shore of the island of Borneo established in 1848 after the acquisition of the island of Labuan from the Sultanate of Brunei in 1846. Apart from the main island, Labuan consist ...

on 28 August 1928. His mother was Bruneian Malay

The Brunei Malay, also called Bruneian Malay (; Jawi: ), is the most widely spoken language in Brunei Darussalam and a lingua franca in some parts of Sarawak and Sabah, such as Labuan, Limbang, Lawas, Sipitang, and Papar.Clynes, A. (2014). ...

, while his grandfather, Sheikh Abdul Hamid, was of Arab descent hence the Sheikh

Sheikh ( , , , , ''shuyūkh'' ) is an honorific title in the Arabic language, literally meaning "elder (administrative title), elder". It commonly designates a tribal chief or a Muslim ulama, scholar. Though this title generally refers to me ...

moniker. He has three brothers who are Sheikh Nikman, Sheikh Muhammad and Sheikh Osman. In addition, Mahmud Saedon

Mahmud Saedon bin Othman (20 December 1943 – 24 June 2002) was a Bruneian writer and Muslim scholar. His proficiency in the legal and Islamic domains, served as the foundation for the nation's giving of diplomas in law and Syar'ie law. Additi ...

is his nephew. He was raised in a family with ties to the Bruneian sultan, whose ancestry predates the initial waves of European colonisation. According to historian Bachamiya A. Hussainmiya, it is not possible to verify the truth about his 'Brunei birth'. Many people claimed he was born in Labuan, but Azahari strongly denied the claims and said he was born in Brunei Town in a house on the site where the Churchill Memorial Museum (currently Royal Regalia Museum) was later built.

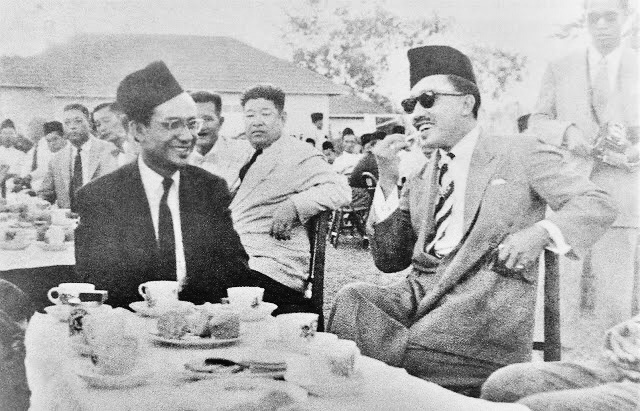

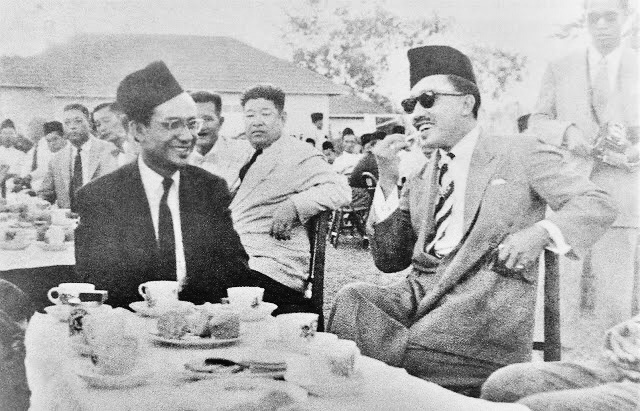

In pre-war Brunei, Azahari had known Omar Ali Saifuddin, the younger brother of the 27th Sultan of Brunei

The Sultan of Brunei is the monarchical head of state of Brunei and head of government in his capacity as prime minister of Brunei. Since independence from the British in 1984, only one sultan has reigned, though the royal institution dates bac ...

, Ahmad Tajuddin. He attended the Brunei Town Catholic mission school (later St. George's School) and studied English there. The Japanese occupation of Brunei

Before the outbreak of World War II in the Pacific, the island of Borneo was divided into five territories. Four of the territories were in the north and under British control – Sarawak, Brunei, Labuan, an island, and British North Borneo; w ...

, they chose Azahari, then fifteen years old, to go to school in the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

and pursue a career in veterinary medicine

Veterinary medicine is the branch of medicine that deals with the prevention, management, medical diagnosis, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, disorder, and injury in non-human animals. The scope of veterinary medicine is wide, covering all a ...

.

Despite going against his parents' wishes, he arrived alone in Jakarta

Jakarta (; , Betawi language, Betawi: ''Jakartè''), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta (; ''DKI Jakarta'') and formerly known as Batavia, Dutch East Indies, Batavia until 1949, is the capital and largest city of Indonesia and ...

with what appeared to be inadequate documentation to sustain his claim he was on a Japanese scholarship, he was temporarily detained by the ''Kempeitai

The , , was the military police of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). The organization also shared civilian secret police that specialized in clandestine and covert operation, counterinsurgency, counterintelligence, HUMINT, interrogated suspects ...

''. He was only allowed to continue south to Buitenzorg

Bogor City (), or Bogor (, ), is a landlocked city in the West Java, Indonesia. Located around south of the national capital of Jakarta, Bogor is the 6th largest city in the Jakarta metropolitan area and the 14th overall nationwide.

when a military administrator from Jakarta interfered. As the only delegate from Brunei, Azahari quickly got to know Ahmad Zaidi Adruce

Ahmad Zaidi Adruce bin Muhammed Noor (; 29 March 1924 – 5 December 2000) was a Malaysian politician who served as the 5th Yang di-Pertua Negeri (Governor) of Sarawak. He was the longest-serving governor in consecutive terms from a single ap ...

, the delegate from Sarawak

Sarawak ( , ) is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia. It is the largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia. Sarawak is located in East Malaysia in northwest Borneo, and is ...

. He did not finish his official training in Java, he stayed on and enrolled at the (Economics School) in 1947, where he spent two of his four years course studying business-related courses.

Independence of Indonesia

Azahari joined theIndonesian independence movement

The Indonesian National Awakening () is a term for the period in the first half of the 20th century, during which people from many parts of the archipelago of Indonesia first began to develop a national consciousness as "Indonesians".

In the ...

against the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

after meeting Mohammad Hatta

Mohammad Hatta ( ; 12 August 1902 – 14 March 1980) was an Indonesian statesman, nationalist, and independence activist who served as the country's first Vice President of Indonesia, vice president as well as the third prime minister. Known as ...

in Java. He became friends with Ahmad Zaidi Adruce

Ahmad Zaidi Adruce bin Muhammed Noor (; 29 March 1924 – 5 December 2000) was a Malaysian politician who served as the 5th Yang di-Pertua Negeri (Governor) of Sarawak. He was the longest-serving governor in consecutive terms from a single ap ...

of Sarawak

Sarawak ( , ) is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia. It is the largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia. Sarawak is located in East Malaysia in northwest Borneo, and is ...

at Bogor

Bogor City (), or Bogor (, ), is a landlocked city in the West Java, Indonesia. Located around south of the national capital of Jakarta, Bogor is the 6th largest city in the Jakarta metropolitan area and the 14th overall nationwide.

, and the two of them started an independence movement for the British-ruled areas of North Borneo

North Borneo (usually known as British North Borneo, also known as the State of North Borneo) was a British Protectorate, British protectorate in the northern part of the island of Borneo, (present-day Sabah). The territory of North Borneo wa ...

. After Sukarno

Sukarno (6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of the Indonesian struggle for independenc ...

and Hatta unilaterally declared Indonesian independence on 17 August 1945, Azahari entered the fight against the Dutch and fought in the Battle of Palembang

The Battle of Palembang was a battle of the Pacific War, Pacific theatre of World War II. It occurred near Palembang, on Sumatra, on 13–15 February 1942. The Royal Dutch Shell oil refineries at nearby Plaju (then Pladjoe) were the major obje ...

and Battle of Surabaya

The Battle of Surabaya () was a major battle in the Indonesian National Revolution fought between regular infantry and militia of the Indonesian nationalist movement and British and British Indian Army, British Indian troops against the re-imp ...

. He enlisted in the '' Badan Keamanan Rakyat'' (BKR), which was General Sudirman

Sudirman (; 24 January 1916 – 29 January 1950) was an Indonesian military officer and revolutionary during the Indonesian National Revolution and the first commander of the Indonesian National Armed Forces.

Born in Purbalingga, Dutch East Ind ...

's predecessor to the Indonesian Army

The Indonesian Army ( (TNI-AD), ) is the army, land branch of the Indonesian National Armed Forces. It has an estimated strength of 300,400 active personnel. The history of the Indonesian Army has its roots in 1945 when the (TKR) "People's Se ...

, in the middle of 1945.

He stayed in the Dutch East Indies for the duration of the Indonesian National Revolution

The Indonesian National Revolution (), also known as the Indonesian War of Independence (, ), was an armed conflict and diplomatic struggle between the Republic of Indonesia and the Dutch Empire and an internal social revolution during A ...

. When Dutch and British soldiers landed in Tanjung Priok

Tanjung Priok is a district in the administrative city of North Jakarta, Indonesia. It hosts the western part of the city's main harbor, the Port of Tanjung Priok (located in Tanjung Priok District and Koja District). The district of Tanjung Prio ...

in September and October 1945, he took part in demonstrations and fighting. Using Japanese weaponry, the BKR—later renamed '' Tentara Keamanan Rakyat'' (TKR)—fought in several clashes at Tanah Tinggi. To make his first mission in Banten

Banten (, , Pegon alphabet, Pegon: بنتن) is the westernmost Provinces of Indonesia, province on the island of Java, Indonesia. Its capital city is Serang and its largest city is Tangerang. The province borders West Java and the Special Capi ...

easier, he learned the Sundanese language

Sundanese ( ; , Sundanese script: , ) is an Austronesian language spoken in Java, primarily by the Sundanese. It has approximately 32 million native speakers in the western third of Java; they represent about 15% of Indonesia's total pop ...

and taught a group of twenty-seven recruits. An important incident that happened while he was there was the killing of an Indonesian commander and seven other people while fighting Dutch soldiers close to Tangerang

Tangerang (Sundanese script, Sundanese: , ) is the List of regencies and cities of Indonesia, city with the largest population in the province of Banten, Indonesia. Located on the western border of Jakarta, it is the sixth largest city proper in ...

. Even though their remains were only found a week after the war, he performed a ceremony for their burial in front of a mosque.

While on a visit to Jakarta, he was captured by the Dutch and sent into British captivity, where he fully revealed to British officials his role in the Indonesian independence movement before being freed. Under the leadership of Raden Muliarwan and Colonel Sambas Atmadinata, Azahari operated in Purwakarta

Purwakarta () is a town and an administrative district () in West Java, Indonesia which serves as the regency seat of the Purwakarta Regency (not to be confused with the district of the same name in Cilegon city). It covers a land area of 24.39& ...

from 1946 to 1950, mostly obtaining intelligence on Dutch operations. For over a month and a half, he covered a large region on foot to report on enemy operations southeast of Jakarta. Because of his commitment to Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

during these operations, he gained respect from Islamic insurgents who ran their own separate operations alongside the nationalist movement.

He participated in the motorcade parade celebrating Indonesian independence

The Proclamation of Indonesian Independence (, or simply ''Proklamasi'') was read at 10:00 Tokyo Standard Time on Friday 17 August 1945 in Jakarta. The declaration marked the start of the diplomatic and armed resistance of the Indonesian Nati ...

from Purwakarta in 1949. In an effort to avoid factional conflicts following victory, district military commanders were entrusted with ensuring an easy transition to Indonesian governance. Despite the considerable Islamic separatist presence in the region, Azahari's nomination as head of the administrative committee for West Java acknowledged his relationship with Darul Islam leaders. Sambas, who had first welcomed his appointment, was taken aback when he foresaw continued instability in the event that talks with Darul Islam would not begin. He quit when Sambas accused him of advocating, but a number of influential people, including the chief of police, the government secretary, and the leader of the West Java Masjumi

The Council of Indonesian Muslim Associations Party (), better known as the Masyumi Party, was a major Islamic political party in Indonesia during the Liberal Democracy Era in Indonesia. It was banned in 1960 by President Sukarno for supporti ...

, pushed him to change his mind. However, he declined. In an additional act of protest, he resigned as a captain in the Indonesian Armed Forces

The Indonesian National Armed Forces (; abbreviated as TNI) are the military forces of the Republic of Indonesia. It consists of the Army (''TNI-AD''), Navy (''TNI-AL''), and Air Force (''TNI-AU''). The President of Indonesia is the Supreme ...

. As soon as he completed this task, he was contacted by Sukamto, the head of the national police, and his deputy to join Captain Soeprapto.

Return to Brunei

After five years, Azahari finally returned to Brunei, but not before encountering challenges organised byBritish Resident

A resident minister, or resident for short, is a government official required to take up permanent residence in another country. A representative of his government, he officially has diplomatic functions which are often seen as a form of in ...

Eric Ernest Falk Pretty, who at first denied his request to come back even after his identity was known. Pretty, who had known his family prior to the war, attempted to convince his uncle, Pengiran Mohammad, not to help arrange for his return, arguing that Sukarno had had a bad effect on him. In the end, he got a travel visa

A visa (; also known as visa stamp) is a conditional authorization granted by a polity to a foreigner that allows them to enter, remain within, or leave its territory. Visas typically include limits on the duration of the foreigner's stay, area ...

from the British embassy in Jakarta and went to Singapore, where he stayed with a Bruneian family until money was supplied, with the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created in 1768 from the Southern Department to deal with colonial affairs in North America (particularly the Thirteen Colo ...

delegating the choice to the Sultan. Only a select handful were originally aware of his covert return to Brunei; he arrived by ship to Labuan

Labuan (), officially the Federal Territory of Labuan (), is an island federal territory of Malaysia. It includes and six smaller islands off the coast of the state of Sabah in East Malaysia. Labuan's capital is Victoria, which is best kno ...

, where he saw his father before being transported by his uncle. Despite this, he arrived in Brunei in October 1952 and once obtaining Sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

Omar Ali Saifuddien III

Omar Ali Saifuddien Sa'adul Khairi Waddien (Jawi script, Jawi: ; 23 September 1914 – 7 September 1986) was the 28th Sultan of Brunei, reigning from 1950 until his abdication in 1967 to his oldest son, Hassanal Bolkiah.

Over the course of his ...

's approval.

Hales, the manager of BMPC, was eager to deport the last forty Indonesian workers in 1953, so he purposefully portrayed them, Azahari, and the dissatisfaction among Bruneian Malay labour force as a danger to the company's ability to produce oil. Azahari's involvement in the independence struggle and his exploits during the Indonesian revolution won him great admiration from the younger generation. However, British oil interests aimed to throw doubt on his intentions and damage his standing with the Sultan. He was seen as a danger to the British Malayan Petroleum Company

Brunei Shell Petroleum (BSP) is a joint venture between the Royal Dutch/Shell Group and government of Brunei, primarily responsible for the exploration and production of oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG). Originally known as the British Mala ...

's (BMPC) economic interests in Brunei, and they described him as a "communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

troublemaker and promoter of Indonesian interests."

Azahari's attempt to form the Brunei Film Production Company (BRUFICO) on 28 October 1952, was a calculated move to draw attention to Brunei's injustices committed by the British. He suggested issuing shares to raise M$250,000. His application was denied because Bruneians were not permitted to independently create these kinds of businesses under the rules in effect at the time. The colonial officials interfered, refusing registration despite the Sultan's original desire to become a stakeholder and igniting a protest against Brunei's restrictive business laws. Together with a sizable group of people, Azahari and his brothers petitioned British Resident J.C.H. Barcroft on 23 January 1953, asking him to reevaluate their application for the Brunei Film Company. The assembly was authorised by State Treasurer E.Q. Cousins at first since the European police officer was not there, but Barcroft eventually declared it to be illegal.

Azahari and his brothers were persuaded to come outside by police officials to prevent any legal complications with their arrests inside their father's home. Once outside, they were taken into custody. On 29 January, Azahari and seven other people—among them his third brother, Sheikh Nikman—were accused of being participants of an unlawful assembly

Unlawful assembly is a legal term to describe a group of people with the mutual intent of deliberate disturbance of the peace. If the group is about to start an act of disturbance, it is termed a rout; if the disturbance is commenced, it is then t ...

and breach of the peace

Breach of the peace or disturbing the peace is a legal term used in constitutional law in English-speaking countries and in a public order sense in the United Kingdom. It is a form of disorderly conduct.

Public order England, Wales and Norther ...

. He was given a six-month sentence imprisonment by the magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judi ...

, Assistant Resident G.A.T. Shaw. Shaw declared that he would not allow Brunei's calm to be disturbed. Despite being in jail, his popularity grew, and an underground movement () began forming, with plans to organize a revolt, take over police stations, release Azahari, and establish a provisional government under his leadership. After his release, from 1953 to 1956, Azahari focused on business activities, frequently traveling between Singapore and Malaya.

His father, Sheikh Mahmud, asked Singaporean attorney David Marshall, to handle an appeal, which was heard on 4 March 1953. His sentence was lowered from six months in prison and a M$500 fine to just three months. Two days before the appeal, a false rumour circulated claiming that his loyal forces were about to rebel, creating a crisis. The rumour stemmed from the desertion of six constables from the oilfield detachment, who left a note indicating they were joining the resistance forces in the jungle. Another rumor suggested all police were poised to surrender their weapons to the Indonesian labour force and carry out mass desertion

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ...

. Early 1953 BMPC investigations revealed that him, with direct help from Indonesia, was aiming to take over police stations, acquire weapons, and gather the European people.

Deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people by a state from its sovereign territory. The actual definition changes depending on the place and context, and it also changes over time. A person who has been deported or is under sen ...

was an option for Azahari in Brunei, but it would require taking the natural-born citizen of Brunei and transferring him to Indonesia. Instead, the chief secretary of Anthony Abell

Anthony Foster Abell (11 December 1906 – 8 October 1994) was a British colonial administrator who served as the governor of Sarawak and concurrently as high commissioner to Brunei from 1950 to 1959. With nine years in office, he held the r ...

suggested a different strategy for handling him. He recommended that Azahari be sent to a secluded area in Brunei and " rusticated." seemed unaware of the consequences of colonial authoritarian control. Despite being highly controversial, Brunei passed rustication laws 'without much trouble,' keeping Azahari in mind. Azahari became close friends with British Resident John Orman Gilbert and concentrated on managing his bus company, which employed 72 people and provided support to many in the oilfields. Gilbert stated that Azahari was no longer a problem and was actively involved in a number of companies, such as a stationery store, a quarry

A quarry is a type of open-pit mining, open-pit mine in which dimension stone, rock (geology), rock, construction aggregate, riprap, sand, gravel, or slate is excavated from the ground. The operation of quarries is regulated in some juri ...

, a stone-crushing company, and a newspaper known as ''Suara Bakti'' (Voice of Service). With the help of Mesir Karuddin, his old prison warden

The warden ( US, Canada) or governor ( UK, Australia), also known as a superintendent (US, South Asia) or director (UK, New Zealand), is the official who is in charge of a prison.

Name

In the United States, Mexico, and Canada, warden is the m ...

, Azahari persisted in pursuing his political objectives despite his commercial endeavours.

Based on the Indonesian revolution, Azahari created a strategic plan for Brunei's anti-colonial uprising. He started by infiltrating the local security system, creating secret groups to educate activists, and looking for a reason for a widespread rebellion. He organised the populace against any oppression by the British government and promoted trade union activities to sabotage the BMPC. He was passionate about gaining independence, but he was torn between supporting the Brunei monarchy and opposing the colonisers. He knew that the monarchy was an essential symbol of Malay unity and that it could not be directly challenged in his fight. In addition to being the head of state, the Sultan of Brunei served as the main authority figure for the British government. As a result, his goal of overthrowing the Sultan and establishing a republic was unlikely to have much support, according to a 1953 report by Abell.

Partai Rakyat Brunei

Azahari's aspirations in politics were triggered by the Alliance Party's overwhelming electoral win in Malaya in 1955 and the call for ''Merdeka

''Merdeka'' ( Jawi: ; , ) is a term in Indonesian and Malay which means "independent" or " free". It is derived from the Sanskrit ''maharddhika'' (महर्द्धिक) meaning "rich, prosperous, and powerful". In the Malay Archipelag ...

'', or independence. He backed Tunku Abdul Rahman

Tunku Abdul Rahman (8 February 19036 December 1990), commonly referred to as Tunku, was a Malaysian statesman who served as prime minister of Malaysia from 1957 to 1970. He previously served as the only chief minister of Federation of Malaya ...

's demand for a unified front for independence that included Northern Borneo by attending the UMNO

The United Malays National Organisation ( abbrev: UMNO; , PEKEMBAR) is a conservative, Malay nationalist political party in Malaysia. As the oldest national political party in the country (since its inception in 1946), UMNO has been known as ...

congress in Kuala Lumpur

Kuala Lumpur (KL), officially the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, is the capital city and a Federal Territories of Malaysia, federal territory of Malaysia. It is the largest city in the country, covering an area of with a census population ...

. In contrast to Tunku's pro-British position, Azahari was more in line with the left-leaning

Centre-left politics is the range of left-wing political ideologies that lean closer to the political centre. Ideologies commonly associated with it include social democracy, social liberalism, progressivism, and green politics. Ideas commonl ...

Partai Rakyat Malaya (PRM), which was anti-British

Anti-British sentiment is the prejudice against, persecution of, discrimination against, fear of, dislike of, or hatred against the British Government, British people, or the culture of the United Kingdom.

Argentina

Historically, anti- ...

and advocated for an enlarged Indonesian–Malay homeland. Disagreements among local leaders and the government's unwillingness to recognise the party caused Azahari's effort to form a PRM branch in Brunei in January 1955 to fail.

He had been contacts with Che'gu Harun Mohammed Amin, also known as Harun Rashid, who had been in Brunei for a long time, from 1955. Harun was the one who initially introduced him to Dr. Burhanuddin al-Helmy

Dato' Seri Dr. Burhanuddin bin Muhammad Nur al-Hilmi ( Jawi: ; 29 August 1911 – 25 October 1969), commonly known as Burhanuddin al-Helmy, was a Malaysian Islamic thinker, anti-colonial nationalist, and politician. He served as the third Pres ...

and Ahmad Boestamam

Ahmad Boestamam (30 November 1920 – 19 January 1983), or Abdullah Thani bin Raja Kechil, was a Malaysian freedom fighter and politician. He was the founding president of Parti Rakyat Malaysia and Parti Marhaen Malaysia and former chairmen of ...

, two left-leaning Malayan politicians, in 1955. He was present during the PRM's debut in Perak

Perak (; Perak Malay: ''Peghok'') is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. Perak has land borders with the Malaysian states of Kedah to the north, Penang to the northwest, Kel ...

on 11 November 1955, which was led by Ahmad. To establish a "Malay Homeland" and rebel against colonial control, the PRM made an appeal to all of the Malays living across the archipelago. Since Azahari wanted an independent Brunei to reject neo-capitalism

Neo-capitalism is an economic ideology which blends some elements of capitalism with other systems. This form of capitalism was new compared to the capitalism in the era before World War II.

Social and economic ideology that arose in the second ...

and "accept Socialist-Nationalist-Democracy" as his slogan, naming his party the Nationalist Socialist Party, its motto connected with him more than that of UMNO.

British Resident Gilbert, Anthony Abell, and Malcolm MacDonald

Malcolm John MacDonald (17 August 1901 – 11 January 1981) was a British politician and diplomat. He was initially a Labour Party (UK), Labour Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP), but in 1931 followed his father ...

were among the people with whom Azahari and his supporters had conversations. He was seen as the most suitable candidate for party head, and the administrators, who were passionate supporters of democratic customs, probably saw the PRB as a good thing. In spite of his anti-colonialist views, Azahari held the British government in high regard, stressing in his first PRB address that they appreciated the British as educators rather than disliking them, particularly if the British acknowledged their rights. The politically underdeveloped bordering regions of Sarawak and North Borneo shared more parallels with Brunei than with the Malayan Federation.

Eventually, on 15 August 1956, Azahari and H.M. Salleh collaborated to establish the Partai Rakyat Brunei (PRB), which became the first political party in Brunei and Northern Borneo and attracted about 10,000 local members rapidly. The party called for Brunei's independence through constitutional routes and condemned all kinds of colonialism in the political, economic, and social sectors. It promised to uphold the Sultan's constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

and attempted to bring together all the states inside the Malay Archipelago

The Malay Archipelago is the archipelago between Mainland Southeast Asia and Australia, and is also called Insulindia or the Indo-Australian Archipelago. The name was taken from the 19th-century European concept of a Malay race, later based ...

into a single Malay country. In terms of economics, the PRB supported the welfare of workers and the fair allocation of public resources. The PRB also pressed the British to grant the locals political

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

and economic rights

Economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR) are socio-economic human rights, such as the right to education, right to housing, right to an adequate standard of living, right to health, victims' rights and the right to science and culture. Econo ...

.

The first written Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

was to be introduced by the Sultan in May 1953, but the process took longer than expected because of multiple requests from the colonial government, the PRB, and the monarch. Seeking to maintain his rule, the Sultan rejected attempts by the British and allies of the Azahari to limit his authority. its advancement was slowed by the PRB's initial refusal to take part in the nominated Local Councils under the 1956 Enactment, despite its desire for a larger involvement in the intended legislative

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers ...

and executive councils. A dissatisfied Azahari, whom the British considered an important political ally, threatened to revolt after long discussions between 1957 and 1959 failed to achieve the democratic goals of the PRB and preserved the Sultan's prerogatives. British officials Gilbert and Abell, viewing Azahari as the only reasonable politician they could negotiate with, discouraged him from quitting politics despite his occasional threats to do so.

Maintaining the Sultan's goodwill required the British government to strike a cautious balance, refraining from actively supporting Azahari's cause. It had little bearing on the discussions because the PRB engaged British attorney Walter Raeburn in May 1957 to deliver their ''Merdeka'' statement, which supported electoral ideals and representative rights, to the Colonial Office. In a failed effort to promote a popular government, he gatecrashed the Colonial Office during the September 1957 London discussions. After Abell rejected his plans for a ministerial style of government, Azahari felt demoralized and considered quitting politics to concentrate on his faltering companies. In the meantime, the Sultan vigorously refuted the PRB's propaganda and separated himself from them.

The PRB saw the Constitution as a setback to their hopes, viewing it as a tool of colonialism that gave Brunei self-rule instead of self-administration. The PRB felt that the Constitution will only help a select few Bruneians and the British, rendering the party powerless and confined to press release protests. In spite of this, he accepted the Sultan's nomination to the temporary Legislative Council out of respect to him. His resolution for his Kalimantan Utara plan was defeated after he took office on 16 April 1958. This prompted him to denounce the council as undemocratic and a colonial relic that may push people toward

The PRB saw the Constitution as a setback to their hopes, viewing it as a tool of colonialism that gave Brunei self-rule instead of self-administration. The PRB felt that the Constitution will only help a select few Bruneians and the British, rendering the party powerless and confined to press release protests. In spite of this, he accepted the Sultan's nomination to the temporary Legislative Council out of respect to him. His resolution for his Kalimantan Utara plan was defeated after he took office on 16 April 1958. This prompted him to denounce the council as undemocratic and a colonial relic that may push people toward communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, signaling his irreversible departure from representative politics. Following his resignation, an irate Azahari complained,

To keep the PRB together, Azahari responded to the various goals of his supporters, with the backing of the together ''Barisan Buruh Bersatu Brunei'' (4B), which promised to support the PRB's initiatives. Tensions increased as the party stepped up its verbal assaults on the administration. To aid in the establishment of a state in North Kalimantan, the PRB started a joint campaign in the middle of June 1961 and established the TNKU. To keep the PRB together, he appealed to the various goals of his supporters, with the backing of the together 4B.

Given his socialist leanings, Azahari was able to establish contact with

To keep the PRB together, Azahari responded to the various goals of his supporters, with the backing of the together ''Barisan Buruh Bersatu Brunei'' (4B), which promised to support the PRB's initiatives. Tensions increased as the party stepped up its verbal assaults on the administration. To aid in the establishment of a state in North Kalimantan, the PRB started a joint campaign in the middle of June 1961 and established the TNKU. To keep the PRB together, he appealed to the various goals of his supporters, with the backing of the together 4B.

Given his socialist leanings, Azahari was able to establish contact with anti-capitalist

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and Political movement, movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. Anti-capitalists seek to combat the worst effects of capitalism and to eventually replace capitalism ...

people, nations, and organisations via collaborating with like-minded Malayan mentors and peers. His travels to Indonesia, Kuching

Kuching ( , ), officially the City of Kuching, is the capital and the most populous city in the States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Sarawak in Malaysia. It is also the capital of Kuching Division. The city is on the Sarawak Ri ...

, and Singapore in 1961 and 1962 put him in touch with groups who were suspected of having ties to communist parties: Partindo

The Indonesia Party (), better known as Partindo, was a nationalist political party in Indonesia that existed before independence and was revived in 1957 as a leftist party.

Pre-independence party

In 1927, future Indonesian president Sukarno esta ...

, the Sarawak United Peoples' Party

The Sarawak United Peoples' Party ( abbrev: SUPP; ) is a multiracial local political party of Malaysia based in Sarawak. The SUPP president is Dr. Sim Kui Hian. He succeeded the post from his predecessor, Peter Chin Fah Kui in 2014. Establish ...

, and the Barisan Sosialis

Barisan Sosialis (BS), also known as the Socialist Front, is a defunct left-wing political party in Singapore. It was formed on 29 July 1961 and was officially registered on 13 August 1961 by the leftist faction of the People's Action Party (PA ...

. By this unintentional link, he was accused of being a communist despite was not being one. In light of Indonesia's Konfrontasi, a Sarawak that supported Azahari would also endanger British access to Brunei's oil deposits.

The British authorities were concerned about his growing closer with Indonesia as he depended on Indonesian assistance for TNKU soldier financing and training and looked to the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

for moral support. He had been traveling to Indonesia since 1959, balancing with old revolutionary comrades who had backed his anti-colonial initiatives. A senior PRB leader visited Jakarta in mid-August 1961 to seek support for him. By October 1961, almost every significant member of the PRB was in Jakarta, and a delegation from the PRB attended the Partindo conference on 23 February 1962.

In August 1962, the district council election were held. With resistance to the Malaysia plan as the centerpiece of its election agenda, the PRB secured 22 out of 23 seats and achieved an unambiguous win. This triumph proved the PRB's enormous popularity and its authority to speak for Bruneians both locally and nationally. The PRB said in January 1961, during its Fifth Annual General Assembly, that it would declare independence in 1963 if it won a sizable majority in the elections.

Brunei revolt

Amidst concerns that a member appointed by the government may turn against the Brunei administration and support PRB resolutions, the Bruneian government repeatedly stopped Legislative Council meetings to stall PRB initiatives. Disappointed by the lack of progress, leaders of the PRB, such as Azahari, looked at other options in light of the political standstill, including possible violent intervention by the TNKU, and pushed for quick democratic changes. This would also be followed by communist protests both directly and indirectly across Malaya, including Singapore. After Zahari Azahari forManila

Manila, officially the City of Manila, is the Capital of the Philippines, capital and second-most populous city of the Philippines after Quezon City, with a population of 1,846,513 people in 2020. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on ...

on 8 December 1962, at two in the morning, Brunei revolt

The Brunei revolt () or the Brunei rebellion of 1962 was a December 1962 insurrection in the British protectorate of Brunei by opponents of its monarchy's proposed inclusion in the Federation of Malaysia. The insurgents were members of the ...

, an armed uprising led by the TNKU, broke out in Brunei. At this point, his British passport

The British passport (or UK passport) is a travel document issued by the United Kingdom or other British dependencies and territories to individuals holding any form of British nationality. It grants the bearer international passage in acco ...

was revoked. He was unlikely to have had much influence over the TNKU's daily operations. However, in his capacity as the spokesperson for Bruneian politics, he made clear that the uprising was really against British colonialism and the Malaysia plan, with the goal of creating a Unitary State of North Borneo led by the Sultan. While in Manila, he declared the formation of his government's war cabinet for Kalimantan Utara, or North Kalimantan. The Philippines Government stayed uncommitted to Azahari, the leader of the Brunei revolt, despite the fact that he was in Manila when it broke out, receiving unofficial financial support and sympathetic hearings from high officials. Azahari's plans for a unitary Bornean state ran embarrassingly counter to the Philippines' claim to Sabah

Sabah () is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia located in northern Borneo, in the region of East Malaysia. Sabah has land borders with the Malaysian state of Sarawak to the southwest and Indonesia's North Kalima ...

. Notably, he has maintained communication with Said Zahari

Said Zahari ( – ) was a Singaporean writer and journalist. He was a former editor-in-chief of the Malay language newspaper '' Utusan Melayu'', and an advocate of unbiased freedom of the press. Although he resided in Malaysia with his family, he ...

and Lim Chin Siong

Lim Chin Siong (; 28 February 1933 – 5 February 1996) was a Singaporean politician and union leader active in Singapore in the 1950s and 1960s. He was one of the founders of the governing People's Action Party (PAP), which has governed the ...

of Barisan Sosialis.

After seizing control of the Seria oil fields quickly and capturing many Europeans as prisoners, the Yassin Affandi

Muhammad Yasin bin Abdul Rahman (19 May 1922 – 18 July 2012), also known as Yassin Affandi, was a Bruneian politician who served as the president of the National Development Party from 2005 to 2010. He worked with A.M. Azahari during the B ...

-led rebels targeted Brunei Town

Bandar Seri Begawan (BSB) is the capital and largest city of Brunei. It is officially a municipal area () with an area of and an estimated population of 100,700 as of 2007. It is part of Brunei–Muara District, the smallest yet most populous ...

's government facilities, including the police station. Sarawak's neighboring regions of North Borneo also saw incidents." After a failed attempt to apprehend the Sultan and force him to accept the revolution, the Sultan went on to request British support. Two companies of the 1/2nd Gurkha Rifles were quickly dispatched from Singapore to Brunei Airport, which was empty on the first night of the uprising, despite early uncertainty. After securing the airport, the Gurkhas advanced on the city and discovered the Sultan in his palace ( Istana Darul Hana) uninjured. The resistance quickly crumbled because the TNKU volunteers, who were just lightly equipped, were unable to hold out against strong force. The Queen's Own Highlanders

The Queen's Own Highlanders (Seaforth and Camerons), officially abbreviated "QO HLDRS," was an infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the Scottish Division. It was in existence from 1961 to 1994.

History 1961–1970

The regiment was ...

and Royal Marines

The Royal Marines provide the United Kingdom's amphibious warfare, amphibious special operations capable commando force, one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighting arms of the Royal Navy, a Company (military unit), company str ...

42 Commando

42 Commando is a unit within the UK Commando Force. Based at Norton Manor, Royal Marines Condor and 42 Commando are based at Bickleigh Barracks, Plymouth. Personnel regularly deploy outside the United Kingdom on operations or training. All Roya ...

were among the British forces that later successfully retook Seria

Seria or officially known as Seria Town (), is a town in Belait District, Brunei. It is located about west from the country's capital Bandar Seri Begawan. The total population was 3,625 in 2016. It was where oil was first struck in Brunei i ...

and other regions. By 16 December, most major settlements were once again under government authority, putting an end to the uprising.

The cause for the defeat of the revolt was believed to be his departure. Despite the British military's superiority, Zaini Ahmad

Zaini bin Haji Ahmad (born 21 January 1935) is a Bruneian civil servant, writer, and nationalist activist who played a significant role in the country's political history. A founding member of the (PRB), Zaini was considered one of A. M. Azaha ...

, his colleague who accompanied Azahari to Manila

Manila, officially the City of Manila, is the Capital of the Philippines, capital and second-most populous city of the Philippines after Quezon City, with a population of 1,846,513 people in 2020. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on ...

, thought that Azahari had to have spearheaded the revolution himself. Later on, Zaini attributed his supporters' turnabout on Azahari's absence. Among the chaos, the rebels perceived the Sultan as the new face of group leadership and, naturally, the center of allegiance. Azahari traveled to Indonesia, where he was given support, encouragement, and safety but was not given official government recognition.

The failed rebellion destroyed any goals for democratic progress and blocked Azahari's plan to establish a Northern Kalimantan State ruled by the Sultan as a constitutional monarchy. Rather, Brunei gave up on democracy and returned to a traditional Malay monarchy. After that, the state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state before, during, o ...

was imposed and is still in place, and Britain gave up trying to set up a representative government.

Life in exile and death

After his defeat, Azahari fled toJakarta

Jakarta (; , Betawi language, Betawi: ''Jakartè''), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta (; ''DKI Jakarta'') and formerly known as Batavia, Dutch East Indies, Batavia until 1949, is the capital and largest city of Indonesia and ...

where he was granted asylum by President Sukarno

Sukarno (6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of the Indonesian struggle for independenc ...

in 1963 and lived in Bogor, West Java. With assistance from Malaysia and Indonesia, he and his allies established an exile government following the failed revolt. Up until around 1975, Malaysia supported his cause in the United Nations, which strained relations with Brunei. But with the conclusion of Konfrontasi and the formation of ASEAN

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations,

commonly abbreviated as ASEAN, is a regional grouping of 10 states in Southeast Asia "that aims to promote economic and security cooperation among its ten members." Together, its member states r ...

, regional diplomatic ties improved, and his goals diminished. The United States' stance on the rebellion contributed to Azahari's inability to secure a visa for the country.

At the age of 75, Azahari passed away in Bogor, Indonesia, on 30 May 2002, while residing in exile.

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* World History Study Guide. "Parti Rakyat Brunei History Summary". Retrieved 15 December 2005. * Sejarah Indonesia "The Sukarno years: 1950 to 1965". Retrieved 15 December 2005. *US Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

. "Brunei". Retrieved 17 September 2010.

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Azahari, A.M. 1928 births 2002 deaths Bruneian people of Arab descent Bruneian rebels Brunei People's Party politicians Naturalised citizens of Indonesia People from Labuan Bruneian Muslims Politicians from the Dutch East Indies