1968 Polish Political Crisis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A series of major student, intellectual and other

/ref> ''Encyclopedia of the Cold War'', Volume 1 By Ruud van Dijk. Page 374.

Taylor & Francis, 2008. . 987 pages. The anti-Zionist campaign began in 1967, and was carried out in conjunction with the

"The Anti-Zionist Campaign in Poland of 1967–1968."

The American Jewish Committee research grant. See: D. Stola, Fighting against the Shadows (reprint), in Robert Blobaum, ed., ''Antisemitism and Its Opponents in Modern Poland''.

/ref> At least 13,000 Poles of Jewish origin emigrated in 1968–1972 as a result of being fired from their positions and various other forms of harassment. Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968 he Anti-Zionist Campaign in Poland 1967–1968 pp. 213, 414, published by Instytut Studiów Politycznych Polskiej Akademii Nauk, Warsaw 2000, Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991 he Political History of Poland 1944–1991 pp. 346–347, Wydawnictwo Literackie, Kraków 2011,

''Book review at Historia.org.pl.''

/ref>Monika Krawczyk (March 2013)

Nie zapomnę o Tobie, Polsko! (I will not forget you, Poland).

Forum Żydów Polskich.

Will 2018 Be as Revolutionary as 1968?

Opowieści o pokoleniu 1968.

''Dwutygodnik'' No. 09/2009. A decade earlier, Poland was a scene of the Poznań 1956 protests and the

The outbreak of the March 1968 unrest was seemingly triggered by a series of events in Warsaw, but in reality, it was a culmination of trends accumulating in Poland over several years. The economic situation was deteriorating and a drastic increase in the prices of meat came into effect in 1967. In 1968, the market was destabilized further by rumors of upcoming currency exchange and the ensuing panic. Higher norms were enforced for industrial productivity with wages reduced at the same time. First Secretary Gomułka was afraid of all changes. The increasingly heavy censorship stifled intellectual life, the boredom of stagnation and the mood of hopelessness (lack of career prospects) generated social conflict.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 346 The disparity between the expectations raised by the

The outbreak of the March 1968 unrest was seemingly triggered by a series of events in Warsaw, but in reality, it was a culmination of trends accumulating in Poland over several years. The economic situation was deteriorating and a drastic increase in the prices of meat came into effect in 1967. In 1968, the market was destabilized further by rumors of upcoming currency exchange and the ensuing panic. Higher norms were enforced for industrial productivity with wages reduced at the same time. First Secretary Gomułka was afraid of all changes. The increasingly heavy censorship stifled intellectual life, the boredom of stagnation and the mood of hopelessness (lack of career prospects) generated social conflict.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 346 The disparity between the expectations raised by the

Marzec '68

. wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 10 March 2014. Dejmek was expelled from the party and subsequently fired from the National Theatre. He left Poland and returned in 1973, to continue directing theatrical productions. In mid-February, a petition signed by 3,000 people (or over 4,200, depending on the source) protesting the censorship of ''Dziady'' was submitted to parliament by student protester Irena Lasota. Gathered for an extraordinary meeting on 29 February with over 400 attendees, the Warsaw chapter of the Polish Writers' Union condemned the ban and other encroachments on free speech rights.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 338 The speakers blamed the faction of Minister Moczar and the party in general for antisemitic incidents, as that campaign was gaining traction. On 4 March, the removal from the

Pytania, które należy postawić. O Marcu '68 z Andrzejem Chojnowskim i Pawłem Tomasikiem rozmawia Barbara Polak.

Pages 2 through 14 of the ''Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej'', nr 3 (86), Marzec 2008. PDF file, direct download 4.79 MB. Internet Archive. The storming of Warsaw University by the (fake) factory worker activists thus came as a total surprise to the students.Dariusz Gawin (19 Sep 2005)

''Marzec 1968 – potęga mitu'' ('March 1968 – the power of the myth')

Ośrodek Myśli Politycznej. The participants of the 8 March rally were met with violent beatings from ORMO volunteer reserve and ZOMO riot squads just as they were about to go home.Piotr Osęka (08.03.2008), .

protest

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration, or remonstrance) is a public act of objection, disapproval or dissent against political advantage. Protests can be thought of as acts of cooperation in which numerous people cooperate ...

s against the ruling Polish United Workers' Party

The Polish United Workers' Party (, ), commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the communist party which ruled the Polish People's Republic as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other legally permitted subordinate minor parti ...

of the Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic (1952–1989), formerly the Republic of Poland (1947–1952), and also often simply known as Poland, was a country in Central Europe that existed as the predecessor of the modern-day democratic Republic of Poland. ...

took place in Poland in March 1968. The crisis led to the suppression of student strikes by security forces

Security forces are statutory organizations with internal security mandates. In the legal context of several countries, the term has variously denoted police and military units working in concert, or the role of irregular military and paramilitar ...

in all major academic centres across the country and the subsequent repression of the Polish dissident movement. It was also accompanied by mass emigration following an antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

(branded "anti-Zionist

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionism. Although anti-Zionism is a heterogeneous phenomenon, all its proponents agree that the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, and the movement to create a sovereign Jewish state in the Palestine (region) ...

") campaign waged by the minister of internal affairs, General Mieczysław Moczar

Mieczysław Moczar (; birth name Mikołaj Diomko, pseudonym ''Mietek'', 23 December 1913 – 1 November 1986) was a Polish communist politician who played a prominent role in the history of the Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's R ...

, with the approval of First Secretary Władysław Gomułka

Władysław Gomułka (; 6 February 1905 – 1 September 1982) was a Polish Communist politician. He was the ''de facto'' leader of Polish People's Republic, post-war Poland from 1947 until 1948, and again from 1956 to 1970.

Born in 1905 in ...

of the Polish United Workers' Party

The Polish United Workers' Party (, ), commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the communist party which ruled the Polish People's Republic as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other legally permitted subordinate minor parti ...

(PZPR). The protests overlapped with the events of the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring (; ) was a period of liberalization, political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected Secretary (title), First Secre ...

in neighboring Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

– raising new hopes of democratic reforms among the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

. The Czechoslovak unrest culminated in the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

On 20–21 August 1968, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four fellow Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Republic of Bulgaria, and the Hungarian People's Republic. The ...

on 20 August 1968. ''Excel HSC modern history'' By Ronald E. Ringer. Page 384./ref> ''Encyclopedia of the Cold War'', Volume 1 By Ruud van Dijk. Page 374.

Taylor & Francis, 2008. . 987 pages. The anti-Zionist campaign began in 1967, and was carried out in conjunction with the

USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

's withdrawal of all diplomatic relations with Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

after the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

, but also involved a power struggle within the PZPR itself. The subsequent purges within the ruling party, led by Moczar and his faction, failed to topple Gomułka's government but resulted in an exile from Poland of thousands of communist individuals of Jewish ancestry, including professionals, party officials and secret police functionaries appointed by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

following the Second World War. In carefully staged public displays of support, factory workers across Poland were assembled to publicly denounce Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

. Dariusz Stola."The Anti-Zionist Campaign in Poland of 1967–1968."

The American Jewish Committee research grant. See: D. Stola, Fighting against the Shadows (reprint), in Robert Blobaum, ed., ''Antisemitism and Its Opponents in Modern Poland''.

Cornell University Press

The Cornell University Press is the university press of Cornell University, an Ivy League university in Ithaca, New York. It is currently housed in Sage House, the former residence of Henry William Sage. It was first established in 1869, maki ...

, 2005.''The world reacts to the Holocaust'' By David S. Wyman, Charles H. Rosenzveig. Ibidem. Pages 120-122./ref> At least 13,000 Poles of Jewish origin emigrated in 1968–1972 as a result of being fired from their positions and various other forms of harassment. Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968 he Anti-Zionist Campaign in Poland 1967–1968 pp. 213, 414, published by Instytut Studiów Politycznych Polskiej Akademii Nauk, Warsaw 2000, Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991 he Political History of Poland 1944–1991 pp. 346–347, Wydawnictwo Literackie, Kraków 2011,

''Book review at Historia.org.pl.''

/ref>Monika Krawczyk (March 2013)

Nie zapomnę o Tobie, Polsko! (I will not forget you, Poland).

Forum Żydów Polskich.

Background

The political turmoil of the late 1960s was exemplified in theWest

West is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some Romance langu ...

by increasingly violent protests against the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

and included numerous instances of protest and revolt, especially among students, that reverberated across Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

in 1968. The movement was reflected in the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

by the events of the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring (; ) was a period of liberalization, political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected Secretary (title), First Secre ...

, beginning 5 January 1968. A wave of protests in Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

marked the high point of a broader series of dissident social mobilization. According to Ivan Krastev, the 1968 movement in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, emphasizing individual sovereignty, was fundamentally different from that in the Eastern Bloc, concerned primarily with national sovereignty.Krastev, Ivan. (21 February 2018)Will 2018 Be as Revolutionary as 1968?

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

In Poland, a growing crisis having to do with communist party control over universities, the literary community, and intellectuals in general, marked the mid-1960s. Those persecuted for political activism on campus included Jacek Kuroń, Karol Modzelewski, Adam Michnik

Adam Michnik (; born 17 October 1946) is a Polish historian, essayist, former Anti-communist resistance in Poland (1944–1989), dissident, Intellectual#Public intellectual, public intellectual, as well as co-founder and editor-in-chief of the P ...

and Barbara Toruńczyk, among others.Barbara ToruńczykOpowieści o pokoleniu 1968.

''Dwutygodnik'' No. 09/2009. A decade earlier, Poland was a scene of the Poznań 1956 protests and the

Polish October

The Polish October ( ), also known as the Polish thaw or Gomułka's thaw, also "small stabilization" () was a change in the politics of the Polish People's Republic that occurred in October 1956. Władysław Gomułka was appointed First Secretar ...

events.

Reaction to Arab–Israeli war of 1967

The events of 1967 and Polish communist leaders' necessity to follow theSoviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

lead altered the relatively benign relations between People's Poland and Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

. The combination of international and domestic factors gave rise in Poland to a campaign of hate against purported internal enemies, among whom the Jews would become the most salient target.Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 7–14

As the Israeli–Arab Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

started on 5 June 1967, the Polish Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

met the following day and made policy determinations, declaring condemnation of "Israel's aggression" and full support for the "just struggle of the Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

countries". First Secretary Władysław Gomułka

Władysław Gomułka (; 6 February 1905 – 1 September 1982) was a Polish Communist politician. He was the ''de facto'' leader of Polish People's Republic, post-war Poland from 1947 until 1948, and again from 1956 to 1970.

Born in 1905 in ...

and Prime Minister Józef Cyrankiewicz went to Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

on 9 June for a Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

conference of communist leaders. The participants deliberated in a depressing atmosphere. The decisions made included the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

's continuation of military and financial support for the Arab states and the breaking of diplomatic relations with Israel, in which only Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

refused to participate.Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 29–46

A media campaign commenced in Poland and was soon followed by "anti-Israeli imperialism" rallies held in various towns and places of employment. After the government delegation's return to Warsaw, Gomułka, pessimistic and fearful of a possible nuclear confrontation and irritated by the reports of support for Israel among many Polish Jews, on 19 June proclaimed at the Trade Union Congress that Israel's aggression had been "met with applause in Zionist circles of Jews – Polish citizens." Gomułka specifically invited "those who feel that these words are addressed to them" to emigrate, but Edward Ochab and some other Politburo members objected and the statement was deleted before the speech's publication. Gomułka did not issue a call for anti-Jewish personnel purges, but the so-called "anti-Zionist" campaign got underway anyway, supported by his close associates Zenon Kliszko and Ignacy Loga-Sowiński. It was eagerly amplified by General Mieczysław Moczar

Mieczysław Moczar (; birth name Mikołaj Diomko, pseudonym ''Mietek'', 23 December 1913 – 1 November 1986) was a Polish communist politician who played a prominent role in the history of the Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's R ...

, minister of internal affairs, by some military leaders who had long been waiting for an opportunity to "settle with the Jews", and by other officials. A list of 382 "Zionists" was presented at the ministry on 28 June and the purge slowly developed, beginning with Jewish generals and other high-ranking officers of the Polish armed forces.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, pp. 334–336 About 150 Jewish military officers were fired in 1967–1968, including Czesław Mankiewicz, national air defense chief. Minister of Defense Marian Spychalski tried to defend Mankiewicz and by doing so compromised his own position.Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 69–78 The Ministry of Internal Affairs renewed its proposal to ban the Jewish organizations from receiving foreign contributions from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Advert

Where and how does this article resemble an WP:SOAP, advert and how should it be improved? See: Wikipedia:Spam (you might trthe Teahouseif you have questions).

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, also known as Joint or JDC, is a J ...

. This time, unlike on previous occasions, the request was quickly granted by the Secretariat of the PZPR's Central Committee and the well-developed Jewish social, educational and cultural organized activities in Poland faced stiff reductions or even practical liquidation.Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 47–68

About 200 people lost their jobs and were removed from the party top leadership in 1967, including Leon Kasman, chief editor of ''Trybuna Ludu

''Trybuna Ludu'' (; ''People's Tribune'') was one of the largest newspapers in communist Poland, which circulated between 1948 and 1990. It was the official media outlet of the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) along with the televised news ...

'', the party's main daily newspaper. Kasman was Moczar's hated rival from the time of the war when he arrived from the Soviet Union and was parachuted into Poland. After March 1968, when Moczar's ministry was finally given the freehand it had long sought, 40 employees were fired from the editorial staff of the Polish Scientific Publishers (PWN). This major state publishing house had produced a number of volumes of the official '' Great Universal Encyclopedia''. Moczar and others protested in the fall of 1967 the supposedly unbalanced treatment of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

issues, namely stressing Jewish martyrdom and the disproportionate numbers of Jews killed in Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe, primarily in occupied Poland, during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocau ...

s.

In the words of Polish scholar Włodzimierz Rozenbaum, the Six-Day War "provided Gomułka with an opportunity 'to kill several birds with one stone': he could use an "anti-Zionist" policy to undercut the appeal of the liberal wing of the party; he could bring forward the Jewish issue to weaken the support for the nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

faction (in the party) and make his own position even stronger..." while securing political prospects for his own supporters.Włodzimierz Rozenbaum, CIAO: Intermarium, ''National Convention of the American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies'', Atlanta, Ga., 8–11 October 1975.

On 19 June 1967, Gomułka warned in his speech: "We don't want an establishment of a fifth column

A fifth column is a group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. The activities of a fifth column can be overt or clandestine. Forces gathered in secret can mobilize ...

in our country". The sentence was deleted from a published version,Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, p. 274 but such views he repeated and developed further in successive speeches, for example on 19 March 1968. On 27 June 1967, the first secretary characterized Romania's position as shameful, predicted production of nuclear arms by Israel and spoke generally of consequences faced by people who had "two souls and two fatherlands".Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 277–279 Following Gomułka's anti-Israel and anti-Jewish rhetoric, the security services began screening officials of Jewish origin and looking for 'hidden Zionists' in Polish institutions.

Protest in Warsaw

The outbreak of the March 1968 unrest was seemingly triggered by a series of events in Warsaw, but in reality, it was a culmination of trends accumulating in Poland over several years. The economic situation was deteriorating and a drastic increase in the prices of meat came into effect in 1967. In 1968, the market was destabilized further by rumors of upcoming currency exchange and the ensuing panic. Higher norms were enforced for industrial productivity with wages reduced at the same time. First Secretary Gomułka was afraid of all changes. The increasingly heavy censorship stifled intellectual life, the boredom of stagnation and the mood of hopelessness (lack of career prospects) generated social conflict.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 346 The disparity between the expectations raised by the

The outbreak of the March 1968 unrest was seemingly triggered by a series of events in Warsaw, but in reality, it was a culmination of trends accumulating in Poland over several years. The economic situation was deteriorating and a drastic increase in the prices of meat came into effect in 1967. In 1968, the market was destabilized further by rumors of upcoming currency exchange and the ensuing panic. Higher norms were enforced for industrial productivity with wages reduced at the same time. First Secretary Gomułka was afraid of all changes. The increasingly heavy censorship stifled intellectual life, the boredom of stagnation and the mood of hopelessness (lack of career prospects) generated social conflict.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 346 The disparity between the expectations raised by the Polish October

The Polish October ( ), also known as the Polish thaw or Gomułka's thaw, also "small stabilization" () was a change in the politics of the Polish People's Republic that occurred in October 1956. Władysław Gomułka was appointed First Secretar ...

movement of 1956 and the actuality of the " real socialism" life of the 1960s led to mounting frustration.Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 13–27

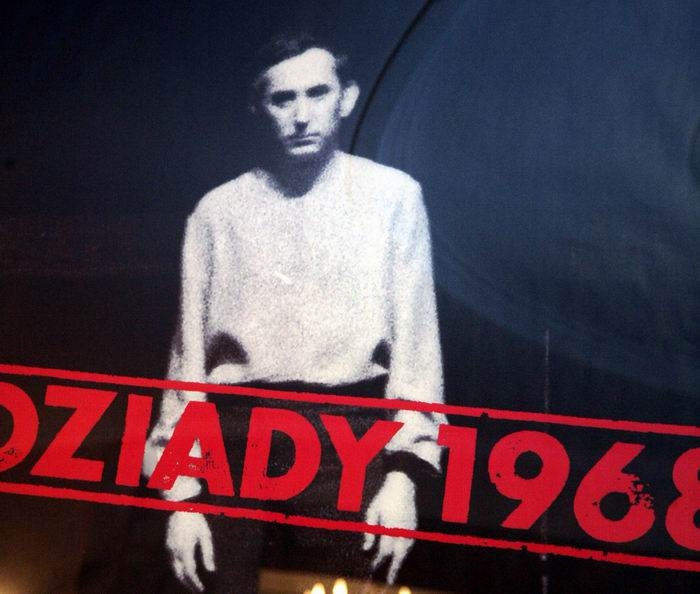

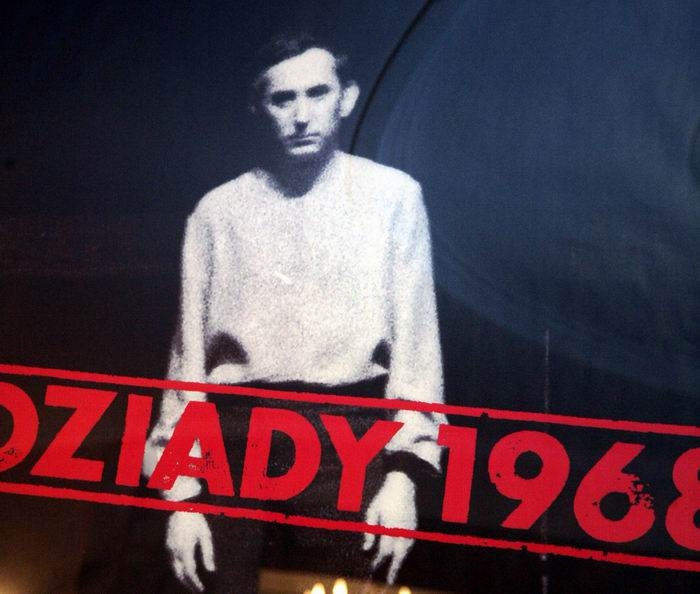

At the end of January 1968, after its poor reception by the Central Committee of the ruling PZPR, the government authorities banned the performance of a Romantic play by Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. He also largely influenced Ukra ...

called '' Dziady'' (written in 1824), directed by Kazimierz Dejmek at the National Theatre, Warsaw

The National Theatre () in Warsaw, Poland, was founded in 1765, during the Polish Enlightenment, by that country's List of Polish monarchs, monarch, Stanisław August Poniatowski. The theatre shares the Grand Theatre, Warsaw, Grand Theatre compl ...

. It was claimed that the play contained Russophobic and anti-Soviet references and represented an unduly pro-religion stance. ''Dziady'' had been staged 11 times, the last time on 30 January. The ban was followed by a demonstration after the final performance, which resulted in numerous police detentions.Adam Leszczyński, ''Marzec '68'' arch 68 7 March 2014Marzec '68

. wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 10 March 2014. Dejmek was expelled from the party and subsequently fired from the National Theatre. He left Poland and returned in 1973, to continue directing theatrical productions. In mid-February, a petition signed by 3,000 people (or over 4,200, depending on the source) protesting the censorship of ''Dziady'' was submitted to parliament by student protester Irena Lasota. Gathered for an extraordinary meeting on 29 February with over 400 attendees, the Warsaw chapter of the Polish Writers' Union condemned the ban and other encroachments on free speech rights.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 338 The speakers blamed the faction of Minister Moczar and the party in general for antisemitic incidents, as that campaign was gaining traction. On 4 March, the removal from the

University of Warsaw

The University of Warsaw (, ) is a public university, public research university in Warsaw, Poland. Established on November 19, 1816, it is the largest institution of higher learning in the country, offering 37 different fields of study as well ...

of dissident

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 2 ...

s Adam Michnik

Adam Michnik (; born 17 October 1946) is a Polish historian, essayist, former Anti-communist resistance in Poland (1944–1989), dissident, Intellectual#Public intellectual, public intellectual, as well as co-founder and editor-in-chief of the P ...

and Henryk Szlajfer, members of the '' Komandosi'' group, was announced by officials. A crowd of some 500 (or about 1,000) students rallying at the university on 8 March was attacked violently by organized "worker activists" (probably plainclothes police) and by police in uniform. Nonetheless, other institutions of higher learning in Warsaw joined the protest a day later.

Student- and intellectual-led movement

Dariusz Gawin of thePolish Academy of Sciences

The Polish Academy of Sciences (, PAN) is a Polish state-sponsored institution of higher learning. Headquartered in Warsaw, it is responsible for spearheading the development of science across the country by a society of distinguished scholars a ...

pointed out that the March 1968 events have been mythologized in subsequent decades beyond their modest original aims, under the lasting influence of former members of '' Komandosi'', a left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

student political activity group. During the 1968 crisis, the dissident academic circles produced very little in terms of written accounts or programs. They experienced a moral shock because of propaganda misrepresentations of their intentions and actions and the unexpectedly violent repressions. They also experienced an ideological shock, caused by the reaction of the authorities (aggression) and society (indifference) to their idealistic attempts to bring about revolutionary reform in the Polish People's Republic. The alienation of the reform movement from the ostensibly socialist system (and their own leftist views) had begun.

The students were naïve in terms of practical politics, but their leaders professed strongly leftist convictions, expressed in brief proclamations distributed in 1968. Following the spirit of the 1964 " revisionist" manifesto by Karol Modzelewski and Jacek Kuroń, they demanded respect for the ideals of the Marxist–Leninist "dictatorship of the proletariat" and principles of socialism. The protesting students sang "The Internationale

"The Internationale" is an international anthem that has been adopted as the anthem of various anarchist, communist, socialist, democratic socialist, and social democratic movements. It has been a standard of the socialist movement since ...

" anthem.Barbara PolakPytania, które należy postawić. O Marcu '68 z Andrzejem Chojnowskim i Pawłem Tomasikiem rozmawia Barbara Polak.

Pages 2 through 14 of the ''Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej'', nr 3 (86), Marzec 2008. PDF file, direct download 4.79 MB. Internet Archive. The storming of Warsaw University by the (fake) factory worker activists thus came as a total surprise to the students.Dariusz Gawin (19 Sep 2005)

''Marzec 1968 – potęga mitu'' ('March 1968 – the power of the myth')

Ośrodek Myśli Politycznej. The participants of the 8 March rally were met with violent beatings from ORMO volunteer reserve and ZOMO riot squads just as they were about to go home.Piotr Osęka (08.03.2008), .

Gazeta Wyborcza

(; ''The Electoral Gazette'' in English) is a Polish nationwide daily newspaper based in Warsaw, Poland. It was launched on 8 May 1989 on the basis of the Polish Round Table Agreement and as a press organ of the Solidarity (Polish trade union), t ...

. The disproportionately brutal reaction of the security forces appeared to many observers to be a provocation perpetrated to aggravate the unrest and facilitate further rounds of repression, in the self-interest of political leaders. A comparable demonstration originated on 9 March at the Warsaw University of Technology

The Warsaw University of Technology () is one of the leading institutes of technology in Poland and one of the largest in Central Europe. It employs 2,453 teaching faculty, with 357 professors (including 145 titular professors). The student body ...

and was also followed by confrontations with the police and arrests. Kuroń, Modzelewski and Michnik were imprisoned again and a majority of the ''Komandosi'' members were detained.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, pp. 339–340 In later accounts, however, the founding mythology of Poland's civil society

Civil society can be understood as the "third sector" of society, distinct from government and business, and including the family and the private sphere.

Within a few days protests spread to

Protesty studenckie. Historia.

Marzec1968.pl IPN.

Marcowy rechot Gomułki

wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 14 March 2014. National coordination by the students was attempted through a 25 March meeting in Wrocław; most of its attendees were jailed by the end of April. On 28 March, students at the University of Warsaw reacted to the firing of prominent faculty by adopting the Declaration of the Student Movement, which presented an outline of mature systemic reforms for Poland. The document formulated a new framework for opposition activities and established a conceptual precedent for the future Solidarity opposition movement postulates. The authorities responded by eliminating several university departments and enlisting many students in the military.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, pp. 344–345 The student protest activities, planned for 22 April, were prevented by the arrest campaign conducted in Warsaw, Kraków and Wrocław. At least 2,725 people were arrested between 7 March and 6 April. According to internal government reports, the suppression was effective, although students were still able to disrupt the

In March 1968, the anti-Zionist campaign, loud propaganda and mass mobilization were greatly intensified. The process of purging Jewish officials, ex-Stalinists, high-ranking rival communists and moral supporters of the current liberal opposition movement, was accelerated.Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 79–114 Roman Zambrowski, Stefan Staszewski, Edward Ochab, Adam Rapacki and Marian Spychalski were among the top echelon party leaders removed or neutralized. Zambrowski, a Jewish veteran of the Polish communist movement, was singled out and purged from the party first (13 March), even though he had been politically inactive for several years and had nothing to do with the current crisis. Former First Secretary Ochab resigned his several high offices to protest "against the antisemitic campaign".Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 344 On 11 April 1968, the ''Sejm'' instituted changes in some major leadership positions. Spychalski, leaving the Ministry of Defense, replaced Ochab in the more titular role as the chairman of the Council of State.

In March 1968, the anti-Zionist campaign, loud propaganda and mass mobilization were greatly intensified. The process of purging Jewish officials, ex-Stalinists, high-ranking rival communists and moral supporters of the current liberal opposition movement, was accelerated.Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 79–114 Roman Zambrowski, Stefan Staszewski, Edward Ochab, Adam Rapacki and Marian Spychalski were among the top echelon party leaders removed or neutralized. Zambrowski, a Jewish veteran of the Polish communist movement, was singled out and purged from the party first (13 March), even though he had been politically inactive for several years and had nothing to do with the current crisis. Former First Secretary Ochab resigned his several high offices to protest "against the antisemitic campaign".Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 344 On 11 April 1968, the ''Sejm'' instituted changes in some major leadership positions. Spychalski, leaving the Ministry of Defense, replaced Ochab in the more titular role as the chairman of the Council of State.

Przegląd socjalistyczny www.przeglad-socjalistyczny.pl. Retrieved 28 March 2014. Moczar himself campaigned ruthlessly in an ultimately failed attempt to become Gomułka's replacement or successor.

/ref> According to Dariusz Stola of the

In Poland, a Grass-Roots Jewish Revival Endures

Poland.

In: David S. Wyman, Charles H. Rosenzveig. ''The World Reacts to the Holocaust''. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996. . An additional 30,000 arrived from the Soviet Union in 1957, but almost 50,000, typically people actively expressing Jewish identity, left Poland in 1957–59, under Gomułka and with his government's encouragement. Approximately 25,000–30,000 Jews lived in Poland by 1967. As a group, they had become increasingly assimilated and secular and had well-developed and functioning Jewish secular institutions. Of the Jews who stayed in Poland, many did so for political and career reasons. Their situation changed after the 1967 Arab–Israeli war and the 1968 Polish academic revolt when the Jews were used as scapegoats by the warring party factions and pressured to emigrate ''en masse'' once more. According to Engel, some 25,000 Jews left Poland during the 1968–70 period, leaving only between 5,000 and 10,000 Jews in the country. Some 11,200 Jews from Poland immigrated to Israel during 1968 and 1969.Communiqué: Investigation regarding communist state officers who publicly incited hatred towards people of different nationality.

''

Nationalism and Ethnosymbolism: History, Culture and Ethnicity in the Formation of Nations.

' Edinburgh University Press, 2007. Page 137-139. See also Michlic (2006), pp 271-277. For complex historical reasons, Jews held many positions of repressive authority under the post-war Polish communist administrations. In March 1968, some of those officials became the center of an organized campaign to equate Jewish origins with Stalinist sympathies and crimes. The political purges, often ostensibly directed at functionaries of the Stalinist era, affected all Polish Jews regardless of background. Prior to the 1967–68 events, Polish-Jewish relations had been a taboo subject in communist Poland. Available information was limited to the dissemination of shallow and distorted official versions of historical events, while much of the traditional social antisemitic resentment was brewing under the surface, despite the scarcity of Jewish targets. Popular antisemitism of the post-war years was closely linked to anticommunist and anti-Soviet attitudes and as such was resisted by the authorities. Because of this historically right-wing orientation of Polish antisemitism, the Jews generally felt safe in communist Poland and experienced a "March shock" when many in the ruling regime adopted the antisemitic views of pre-war Polish nationalists to justify an application of aggressive propaganda and psychological terror. The outwardly Stalinist character of the campaign was paradoxically combined with anti-Stalinist and anti-Żydokomuna rhetoric.Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 145–150 The media "exposed" various past and present Jewish conspiracies directed against socialist Poland, often using prejudicial Jewish stereotypes, which supposedly added up to a grand Jewish anti-Polish scheme.

Stalinowscy uciekinierzy

Bibula, 2011, Baltimore-Washington, DC, ISSN 1542-7986, reprinted from Antysocjalistyczne Mazowsze, 2006''Nakaz aresztowania stalinowskiego sędziego już w Szwecji'' ('The arrest warrant for the Stalinist judge already in Sweden'). Gazeta.pl, 27 October 2010. Between 1961 and 1967, the average rate of Jewish emigration from Poland was 500–900 persons per year. In 1968, a total of 3,900 Jews applied to leave the country. Between January and August 1969, the number of emigrating Jews was almost 7,300, all according to records of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The security organs maintained comprehensive data on persons with "family background in Israel" or of Jewish origin, including those dismissed from their positions and those who did not hold any official positions but applied for emigration to Israel.

Komunizm, intelektualiści, Kościół

13 October 2010,

March '68, Institute of National Remembrance

at Prague Writers' Festival

The Limits of Interpretation: Umberto Eco on Poland's 1968 Student Protests

Andrea Genest, ''From Oblivion to Memory. Poland, the Democratic Opposition and 1968''

Tom Junes, ''The Polish 1968 Student Revolt''

Antisemitism and Its Opponents in Modern Poland

', Robert Blobaum,

Poland marks 50 years since 1968 anti-Semitic purge

' {{DEFAULTSORT:1968 Polish Political Crisis 1968 in Poland, Polish political crisis 1968 protests, Poland Antisemitism in Poland Dissident movement in the People's Republic of Poland History of the Jews in the Polish People's Republic Anti-Zionism in Poland Protests in Poland Anti-communism in Poland 1968 in politics, Polish political crisis March 1968 in Europe Left-wing antisemitism Democratic backsliding in Poland Expulsions of Jews 1968 labor disputes and strikes Socialist antisemitism Anti-Israeli sentiment in Europe

Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

, Lublin

Lublin is List of cities and towns in Poland, the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the centre of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin i ...

, Gliwice

Gliwice (; , ) is a city in Upper Silesia, in southern Poland. The city is located in the Silesian Highlands, on the Kłodnica river (a tributary of the Oder River, Oder). It lies approximately 25 km west from Katowice, the regional capital ...

, Katowice

Katowice (, ) is the capital city of the Silesian Voivodeship in southern Poland and the central city of the Katowice urban area. As of 2021, Katowice has an official population of 286,960, and a resident population estimate of around 315,000. K ...

, and Łódź

Łódź is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located south-west of Warsaw. Łódź has a population of 655,279, making it the country's List of cities and towns in Polan ...

(from 11 March), Wrocław

Wrocław is a city in southwestern Poland, and the capital of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. It is the largest city and historical capital of the region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the Oder River in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Eu ...

, Gdańsk

Gdańsk is a city on the Baltic Sea, Baltic coast of northern Poland, and the capital of the Pomeranian Voivodeship. With a population of 486,492, Data for territorial unit 2261000. it is Poland's sixth-largest city and principal seaport. Gdań ...

, and Poznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

(12 March). The frequent demonstrations at the above locations were brutally suppressed by the police. Mass student strikes took place in Wrocław on 14–16 March, Kraków on 14–20 March, and Opole. A student committee at Warsaw University (11 March) and an inter-university committee in Kraków (13 March) were formed; attempts to organize were also made in Łódź and Wrocław. Efforts aimed at getting industrial workers involved, for example, employees of the state enterprises in Gdańsk, Wrocław and Kraków's Nowa Huta produced no tangible effects. But on 15 March in Gdańsk, 20,000 students and workers marched and fought several types of security forces totalling 3,700 men, into the late evening.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 342

University students comprised less than 25% of those arrested for participating in opposition activities in March and April 1968 (their numerical predominance in the movement was a part of the subsequent myth, wrote historian Łukasz Kamiński). The leading role in the spreading countrywide street protests was played by young factory workers and secondary school students. Łukasz KamińskiProtesty studenckie. Historia.

Marzec1968.pl IPN.

Repressions

A media campaign besmirching targeted groups and individuals was conducted from 11 March. The Stalinist and Jewish ("non-Polish") roots of the supposed instigators were "exposed" and most printed press participated in the propagation of slander, with the notable exceptions of '' Polityka'' and ''Tygodnik Powszechny

''Tygodnik Powszechny'' (, ''The Common Weekly'') is a Polish Roman Catholic weekly magazine, published in Kraków, which focuses on social, cultural and political issues. It was established in 1945 under the auspices of Cardinal Adam Stefan Sap ...

''. Mass "spontaneous" rallies at places of employment and in squares of major cities took place. The participants demanded "Students resume their studies, writers their writing", "Zionists go to Zion

Zion (; ) is a placename in the Tanakh, often used as a synonym for Jerusalem as well as for the Land of Israel as a whole.

The name is found in 2 Samuel (), one of the books of the Tanakh dated to approximately the mid-6th century BCE. It o ...

!", or threatened "We'll tear off the head of the anti-Polish hydra". On 14 March, regional party secretary Edward Gierek in Katowice

Katowice (, ) is the capital city of the Silesian Voivodeship in southern Poland and the central city of the Katowice urban area. As of 2021, Katowice has an official population of 286,960, and a resident population estimate of around 315,000. K ...

used strong language addressing the Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( ; ; ; ; Silesian German: ; ) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located today mostly in Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic. The area is predominantly known for its heav ...

n crowds: (people who want to) "make our peaceful Silesian water more turbid ... those Zambrowskis, Staszewskis, Słonimskis and the company of the Kisielewski and Jasienica kind ... revisionists, Zionists, lackeys of imperialism ... Silesian water will crush their bones ...".Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, pp. 340–341 Jerzy Eisler, ''Siedmiu wspaniałych poczet pierwszych sekretarzy KC PZPR'' he Magnificent Seven: First Secretaries of KC PZPR Wydawnictwo Czerwone i Czarne, Warszawa 2014, , pp. 272-275 Gierek introduced a new element during his speech: a statement of support for First Secretary Gomułka, who so far had been silent on the student protests, Zionism and other currently pressing issues.

This initial reluctance of the top leadership to express their position ended with a speech by Gomułka on 19 March. He eliminated the possibility of government negotiations with the strikers, extinguishing the participants' hope for a quick favorable settlement. Gomułka's speech, delivered before three thousand ("outstanding during the difficult days") party activists, was full of anti-intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

accusations. The party management realized, he made it clear, that it was too early to fully comprehend and evaluate the nature and scope of the present difficulties. Gomułka sharply attacked the opposition leaders and named the few writers he particularly abhorred (Kisielewski, Jasienica and Szpotański), but offered a complex and differentiated analysis of the situation in Poland (Słonimski was named as an example of a Polish citizen whose sentiments were "cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Internationalism

* World citizen, one who eschews traditional geopolitical divisions derived from national citizenship

* Cosmopolitanism, the idea that all of humanity belongs to a single moral community

* Cosmopolitan ...

").Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 115–135 The first secretary attempted to pacify the growing antisemitic wave, asserting that most citizens of Jewish origin were loyal to Poland and were not a threat. Loyalty to Poland and socialism, not ethnicity, was the only criterion, the party valued highly those who had contributed and was opposed to any phenomena of antisemitic nature. It was understood that some people could feel ambivalent about where they belonged, and if some felt definitely more closely connected with Israel, Gomułka expected them to eventually emigrate. However, it may have been too late for such reasoned arguments and the carefully screened audience did not react positively: their collective display of hatred was shown on national television. Gomułka's remarks (reviewed, corrected and approved in advance by members of the Politburo and the Central Committee) were criticized a few days later at the meeting of first secretaries of the provincial party committees and the anti-Zionist campaign continued unabated.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 343 The internal bulletin of Mieczysław Moczar

Mieczysław Moczar (; birth name Mikołaj Diomko, pseudonym ''Mietek'', 23 December 1913 – 1 November 1986) was a Polish communist politician who played a prominent role in the history of the Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's R ...

's Ministry of Internal Affairs spoke of a lack of clear declaration on Zionism on Gomułka's part and of "public hiding of criminals". Such criticism of the top party leader was unheard of and indicated the increasing influence and determination of Moczar's faction. In public, Moczar concentrated on issuing condemnations of the communists who came after the war from the Soviet Union and persecuted Polish patriots (including, from 1948, Gomułka himself, which may in part explain the first secretary's failure to dissociate himself from and his tacit approval of anti-Jewish excesses). The purges and attempts to resolve the power struggle at top echelons of the party entered their accelerated phase.

The mass protest movement and the repressions continued throughout March and April. The revolt was met with the dissolution of entire academic departments, the expulsion of thousands of students and many sympathizing faculty members (including Zygmunt Bauman

Zygmunt Bauman (; ; 19 November 1925 – 9 January 2017) was a Polish–British sociologist and philosopher. He was driven out of the Polish People's Republic during the 1968 Polish political crisis and forced to give up his Polish citizenship. ...

, Leszek Kołakowski

Leszek Kołakowski (; ; 23 October 1927 – 17 July 2009) was a Polish philosopher and historian of ideas. He is best known for his critical analysis of Marxism, Marxist thought, as in his three-volume history of Marxist philosophy ''Main Current ...

and Stefan Żółkiewski), arrests and court trials.Andrzej Brzeziecki, ''Marcowy rechot Gomułki'' omułka's March gurgle of laughter 12 March 2013Marcowy rechot Gomułki

wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 14 March 2014. National coordination by the students was attempted through a 25 March meeting in Wrocław; most of its attendees were jailed by the end of April. On 28 March, students at the University of Warsaw reacted to the firing of prominent faculty by adopting the Declaration of the Student Movement, which presented an outline of mature systemic reforms for Poland. The document formulated a new framework for opposition activities and established a conceptual precedent for the future Solidarity opposition movement postulates. The authorities responded by eliminating several university departments and enlisting many students in the military.Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, pp. 344–345 The student protest activities, planned for 22 April, were prevented by the arrest campaign conducted in Warsaw, Kraków and Wrocław. At least 2,725 people were arrested between 7 March and 6 April. According to internal government reports, the suppression was effective, although students were still able to disrupt the

May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the Northern Hemisphere's March equinox, spring equinox and midsummer June solstice, solstice. Festivities ma ...

ceremonies in Wrocław. Except for the relatively few well-recognized protest leaders, the known participants of the 1968 revolt generally did not reappear in later waves of opposition movement in Poland. Andrzej Friszke,, Intermarium, Volume 1, Number 1, 1997; translated from Polish. Original published in Wiez (March 1994).

By mid-March, the protest campaign had spread to smaller towns. The distribution of fliers was reported in one hundred towns in March, forty in April, and, despite numerous arrests, continued even during the later months. Street demonstrations occurred in several localities in March. In different cities, the arrests and trials proceeded at a different pace, in part because of the discretion exercised by local authorities. Gdańsk had by far the highest rate of both the "penal-administrative procedures" and the cases that actually went to courts. The largest proportion of the arrested and detained nationwide during the March/April unrest belonged to the "workers" category.

A few dared to openly defend the students, including some writers, bishops, and the small parliamentary group of Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

deputies '' Znak'', led by Jerzy Zawieyski. ''Znak'' submitted an official interpellation on 11 March, addressed to the prime minister. They questioned the brutal anti-student interventions by the police and inquired about the government's intentions regarding the democratic demands of the students and of the "broad public opinion".

Following the Politburo meeting on 8 April, during which Stefan Jędrychowski strongly criticized the antisemitic campaign but a majority of the participants expressed the opposite view or supported Gomułka's "middle" course, a ''Sejm

The Sejm (), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (), is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of the Third Polish Republic since the Polish People' ...

'' session indirectly dealt with the crisis from the 9th to the 11th of April. Prime Minister Józef Cyrankiewicz asserted that the Radio Free Europe

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) is a media organization broadcasting news and analyses in 27 languages to 23 countries across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Middle East. Headquartered in Prague since 1995, RFE/RL ...

used the ''Znak'' interpellation for its propaganda. Other speakers claimed that the interpellation was primarily aimed at getting the hostile foreign interests involved in Poland's affairs. Zawieyski spoke in a conciliatory tone, directing his comments and appealing to Gomułka and Zenon Kliszko, recognizing them as victims of the past ( Stalinist) political persecution. He interpreted the recent beating by "unknown assailants" of Stefan Kisielewski

Stefan Kisielewski (7 March 1911 in Warsaw – 27 September 1991 in Warsaw, Poland), nicknames Kisiel, Julia Hołyńska, Teodor Klon, Tomasz Staliński, was a Polish writer, publicist, composer and politician, and one of the members of Znak, one ...

, a Catholic publicist, as an attack on a representative of the Polish culture. The party leaders responded by terminating Zawieyski's membership in the Polish Council of State

The Council of State of the Polish People's Republic, Republic of Poland () was introduced by the Small Constitution of 1947 as an organ of executive (government), executive power. The Council of State consisted of the President of Poland, Presid ...

, a collective head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...

organ, and banning him from holding a political office in the future. The participants in the public ''Sejm'' debate concentrated on attacking ''Znak'' and avoided altogether discussing the events and issues of the March protests or their suppression (the subjects of the interpellation).

The effectiveness of the ORMO interventions on university campuses and the eruption of further citizen discontent (see 1970 Polish protests) prompted the Ministry of Public Security

Ministry of Public Security can refer to:

* Ministry of Justice and Public Security (Brazil)

* Ministry of Public Security of Burundi

* Ministry of Public Security (Chile)

* Ministry of Public Security (China)

* Ministry of Public Security of Co ...

to engage in massive expansion of this force, which at its peak in 1979 reached over 450,000 members.

Anti-Zionist/Jewish mobilization and purges, party politics

In March 1968, the anti-Zionist campaign, loud propaganda and mass mobilization were greatly intensified. The process of purging Jewish officials, ex-Stalinists, high-ranking rival communists and moral supporters of the current liberal opposition movement, was accelerated.Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 79–114 Roman Zambrowski, Stefan Staszewski, Edward Ochab, Adam Rapacki and Marian Spychalski were among the top echelon party leaders removed or neutralized. Zambrowski, a Jewish veteran of the Polish communist movement, was singled out and purged from the party first (13 March), even though he had been politically inactive for several years and had nothing to do with the current crisis. Former First Secretary Ochab resigned his several high offices to protest "against the antisemitic campaign".Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 344 On 11 April 1968, the ''Sejm'' instituted changes in some major leadership positions. Spychalski, leaving the Ministry of Defense, replaced Ochab in the more titular role as the chairman of the Council of State.

In March 1968, the anti-Zionist campaign, loud propaganda and mass mobilization were greatly intensified. The process of purging Jewish officials, ex-Stalinists, high-ranking rival communists and moral supporters of the current liberal opposition movement, was accelerated.Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 79–114 Roman Zambrowski, Stefan Staszewski, Edward Ochab, Adam Rapacki and Marian Spychalski were among the top echelon party leaders removed or neutralized. Zambrowski, a Jewish veteran of the Polish communist movement, was singled out and purged from the party first (13 March), even though he had been politically inactive for several years and had nothing to do with the current crisis. Former First Secretary Ochab resigned his several high offices to protest "against the antisemitic campaign".Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia polityczna Polski 1944–1991, p. 344 On 11 April 1968, the ''Sejm'' instituted changes in some major leadership positions. Spychalski, leaving the Ministry of Defense, replaced Ochab in the more titular role as the chairman of the Council of State. Wojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski ( ; ; 6 July 1923 – 25 May 2014) was a Polish military general, politician and ''de facto'' leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1981 until 1989. He was the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party ...

became the new minister of defense. Rapacki, another opponent of antisemitic purges, was replaced by Stefan Jędrychowski at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A new higher education statute was designed to give the government greater control over the academic environment.

Gomułka considered revisionism rather than "Zionism" to be the main "danger". According to historian Dariusz Stola, the first secretary, whose wife was Jewish, harbored no antisemitic prejudices. But he opportunistically and instrumentally allowed and accepted the anti-Jewish initiative of Minister Moczar and the secret services Moczar controlled. The campaign gave Gomułka the tools he needed to combat the intellectual rebellion, prevent it from spreading into the worker masses (by "mobilizing" them and channelling their frustration against the stealth and alien "enemy"), resolve the party rivalries ultimately to his own advantage and stabilize the situation in Poland at the dangerous for the party time of the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring (; ) was a period of liberalization, political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected Secretary (title), First Secre ...

liberalizing movement in Czechoslovakia. Many Poles (irrespective of ethnic background) were accused of being Zionists. They were expelled from the party and/or had their careers terminated by policies that were cynical, prejudicial, or both. Long (sometimes conducted over several days) party meetings and discussions took place at the end of March and in early April within various state institutions and enterprises. They dealt with the "Zionism" issue and were devoted to the identification of those responsible and guilty (within the institution's own ranks), their expulsion from the party and demands for their removal from the positions they held.

Attempts were made to steer the attention of the general public away from the student movement and advocacy for social reform, centered around the defense of freedom of speech for intellectuals and artists and the right to criticize the regime and its policies. Moczar, the leader of the hardline Stalinist faction of the party, blamed the student protests on "Zionists" and used the protest activity as a pretext for a larger antisemitic campaign (officially described as "anti-Zionist") and party purges. In reality, the student and intellectual protests were generally not related to Zionism or other Jewish issues. The propagated idea of the "Zionist inspiration" of student rebellion originated in part from the presence of children of Jewish communists among those contesting the political order, including especially members of the ''Komandosi'' group. To augment their numbers, figures of speech such as the "Michniks, Szlajfers, Zambrowskis" were used. The national strike call from Warsaw (13 March) opposed both antisemitism and Zionism.George Katsiaficas, ''The Imagination of the New Left: A Global Analysis of 1968'', pp. 66–70. One banner hung at a Rzeszów

Rzeszów ( , ) is the largest city in southeastern Poland. It is located on both sides of the Wisłok River in the heartland of the Sandomierz Basin. Rzeszów is the capital of the Subcarpathian Voivodeship and the county seat, seat of Rzeszów C ...

high school on 27 April read: "We hail our Zionist comrades."

However, Gomułka warned that "Zionism and antisemitism are two sides of the same nationalist medal" and insisted that communism rejects all forms of nationalism. According to Gomułka, who rejected the Western allegations of antisemitism, "Official circles in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

have involved themselves in the dirty anti-Polish campaign by making statements accusing Poland of antisemitism. We propose that the ruling circles in the United States check whether American citizens of Polish descent have ever had or have now the same opportunities that Polish citizens of Jewish descent have for good living conditions and education and for occupying positions of responsibility. Then it would emerge clearly who might accuse whom of national discrimination." He went on to say that "the Western Zionist centers that today charge us with antisemitism failed to lift a finger when Hitler's genocide policies exterminated Jews in subjugated Poland, punishing Poles who hid and helped the Jews with death." The party leader was responding to a wave of Western criticism and took advantage of some published reports that were incompatible with the Polish collective memory of historical events, World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

in particular.

The Moczar challenge, often presented in terms of competing political visions (he was the informal head of the nationalist communist party faction known as "the Partisans"), reflected, according to historian Andrzej Chojnowski, primarily a push for a generational change in the party leadership and at other levels, throughout the country. By 1968 Gomułka, whose public relations skills were poor, was unpopular and had lost touch with the population he ruled. Personnel changes, resisted by Gomułka, were generally desired and expected, and in the party, General Moczar was the alternative. Large numbers of generally younger functionaries mobilized behind him, motivated by the potential opportunity to advance their stagnant careers. Finding scapegoats (possibly by just claiming that someone was enthusiastic about the Israeli victory) and becoming their replacements meant in 1968 progress in that direction. The Moczar faction's activity was one of the major factors that contributed to the 1968 uproar, but the overdue generational change within the party materialized fully only when Edward Gierek replaced Gomułka in December 1970.Andrzej Werblan, ''Miejsce ekipy Gierka w dziejach Polski Ludowej'' he role of the Gierek's team in the history of People's Polandbr>The role of the Gierek's teamPrzegląd socjalistyczny www.przeglad-socjalistyczny.pl. Retrieved 28 March 2014. Moczar himself campaigned ruthlessly in an ultimately failed attempt to become Gomułka's replacement or successor.

Emigration of Polish citizens of Jewish origin

In a parliamentary speech on 11 April 1968, Prime Minister Cyrankiewicz spelled out the government's official position: "Loyalty to socialist Poland and imperialist Israel is not possible simultaneously. ... Whoever wants to face these consequences in the form of emigration will not encounter any obstacle." The departing had their Polish citizenship revoked. Historian David Engel of theYIVO

YIVO (, , short for ) is an organization that preserves, studies, and teaches the cultural history of Jewish life throughout Eastern Europe, Germany, and Russia as well as orthography, lexicography, and other studies related to Yiddish. Estab ...

Institute wrote: "The Interior Ministry compiled a card index of all Polish citizens of Jewish origin, even those who had been detached from organized Jewish life for generations. Jews were removed from jobs in public service, including from teaching positions in schools and universities. The pressure was placed upon them to leave the country by bureaucratic actions aimed at undermining their sources of livelihood and sometimes even by physical brutality."The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe: ''Poland since 1939'' by David Engel/ref> According to Dariusz Stola of the

Polish Academy of Sciences

The Polish Academy of Sciences (, PAN) is a Polish state-sponsored institution of higher learning. Headquartered in Warsaw, it is responsible for spearheading the development of science across the country by a society of distinguished scholars a ...

, "the term 'anti-Zionist campaign' is misleading in two ways since the campaign began as an anti-Israeli policy but quickly turned into an anti-semitic campaign, and this evident anti-Jewish character remained its distinctive feature". The propaganda equated Jewish origins with Zionist sympathies and thus disloyalty to communist Poland. Antisemitic slogans were used in rallies. Prominent Jews, supposedly of Zionist beliefs, including academics, managers and journalists, lost their jobs. According to the Polish state's Institute of National Remembrance

The Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation (, abbreviated IPN) is a Polish state research institute in charge of education and archives which also includes two public prosecutio ...

(IPN), which investigated events that took place in 1968–69 in Łodź, "in each case the decision of dismissal was preceded by a party resolution about expelling from the party".

According to Jonathan Ornstein, of the 3.5 million Polish Jews prior to World War II, 350,000 or fewer remained after the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

.Ornstein, Jonathan. (26 February 2018)In Poland, a Grass-Roots Jewish Revival Endures

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

. Retrieved 17 March 2018. Most survivors who claimed their Jewish nationality status at the end of World War II, including those who registered with the Central Committee of Polish Jews in 1945, had emigrated from postwar Poland already in its first years of existence. According to David Engel's estimates, of the fewer than 281,000 Jews present in Poland at different times before July 1946, only about 90,000 were left in the country by the middle of 1947. Fewer than 80,000 remained by 1951, when the government prohibited emigration to Israel.Michael C. Steinlauf.Poland.

In: David S. Wyman, Charles H. Rosenzveig. ''The World Reacts to the Holocaust''. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996. . An additional 30,000 arrived from the Soviet Union in 1957, but almost 50,000, typically people actively expressing Jewish identity, left Poland in 1957–59, under Gomułka and with his government's encouragement. Approximately 25,000–30,000 Jews lived in Poland by 1967. As a group, they had become increasingly assimilated and secular and had well-developed and functioning Jewish secular institutions. Of the Jews who stayed in Poland, many did so for political and career reasons. Their situation changed after the 1967 Arab–Israeli war and the 1968 Polish academic revolt when the Jews were used as scapegoats by the warring party factions and pressured to emigrate ''en masse'' once more. According to Engel, some 25,000 Jews left Poland during the 1968–70 period, leaving only between 5,000 and 10,000 Jews in the country. Some 11,200 Jews from Poland immigrated to Israel during 1968 and 1969.Communiqué: Investigation regarding communist state officers who publicly incited hatred towards people of different nationality.

''

Institute of National Remembrance

The Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation (, abbreviated IPN) is a Polish state research institute in charge of education and archives which also includes two public prosecutio ...

'', Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

. Publication on Polish site of IPN: 25 July 2007.

From the end of World War II, the Soviet-imposed government in Poland, lacking strong popular support, found it expedient to depend disproportionately on Jews for performing clerical and administrative jobs and many Jews rose to high positions within the political and internal security ranks. Consequently, as noted by historian Michael C. Steinlauf – "their group profile ever more closely resembled the mythic Żydokomuna" (see also Jewish Bolshevism

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an antisemitic and anti-communist conspiracy theory that claims that the Russian Revolution of 1917 was a Jewish plot and that Jews controlled the Soviet Union and international communist moveme ...

).Steven Elliott Grosby, Athena S. Leoussi. Nationalism and Ethnosymbolism: History, Culture and Ethnicity in the Formation of Nations.

' Edinburgh University Press, 2007. Page 137-139. See also Michlic (2006), pp 271-277. For complex historical reasons, Jews held many positions of repressive authority under the post-war Polish communist administrations. In March 1968, some of those officials became the center of an organized campaign to equate Jewish origins with Stalinist sympathies and crimes. The political purges, often ostensibly directed at functionaries of the Stalinist era, affected all Polish Jews regardless of background. Prior to the 1967–68 events, Polish-Jewish relations had been a taboo subject in communist Poland. Available information was limited to the dissemination of shallow and distorted official versions of historical events, while much of the traditional social antisemitic resentment was brewing under the surface, despite the scarcity of Jewish targets. Popular antisemitism of the post-war years was closely linked to anticommunist and anti-Soviet attitudes and as such was resisted by the authorities. Because of this historically right-wing orientation of Polish antisemitism, the Jews generally felt safe in communist Poland and experienced a "March shock" when many in the ruling regime adopted the antisemitic views of pre-war Polish nationalists to justify an application of aggressive propaganda and psychological terror. The outwardly Stalinist character of the campaign was paradoxically combined with anti-Stalinist and anti-Żydokomuna rhetoric.Dariusz Stola, Kampania antysyjonistyczna w Polsce 1967 - 1968, pp. 145–150 The media "exposed" various past and present Jewish conspiracies directed against socialist Poland, often using prejudicial Jewish stereotypes, which supposedly added up to a grand Jewish anti-Polish scheme.

West German

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republic after its capital c ...

-Israeli and American-Zionist anti-Poland blocs were also "revealed". In Poland, it was claimed, the old Jewish Stalinists were secretly preparing their own return to power, to thwart the Polish October