1964–1965 Scripto Strike on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Workers for the

In 1946, the USW again tried to organize a union at the Scripto plant, and following a union vote, they began to officially represent the workers in February of that year. The USW's success was due in large part to support from local

In 1946, the USW again tried to organize a union at the Scripto plant, and following a union vote, they began to officially represent the workers in February of that year. The USW's success was due in large part to support from local

By August 1963, the ICWU had obtained enough authorization cards that they could petition for an NLRB election. The company agreed to an election in late September. In the meantime, hoping to prevent a successful union vote, the company instituted several changes, including the formation of an employee committee and the removal of racial segregation signs from the plant's bathrooms and water fountains. In the ensuing six weeks, the union focused on building

By August 1963, the ICWU had obtained enough authorization cards that they could petition for an NLRB election. The company agreed to an election in late September. In the meantime, hoping to prevent a successful union vote, the company instituted several changes, including the formation of an employee committee and the removal of racial segregation signs from the plant's bathrooms and water fountains. In the ensuing six weeks, the union focused on building

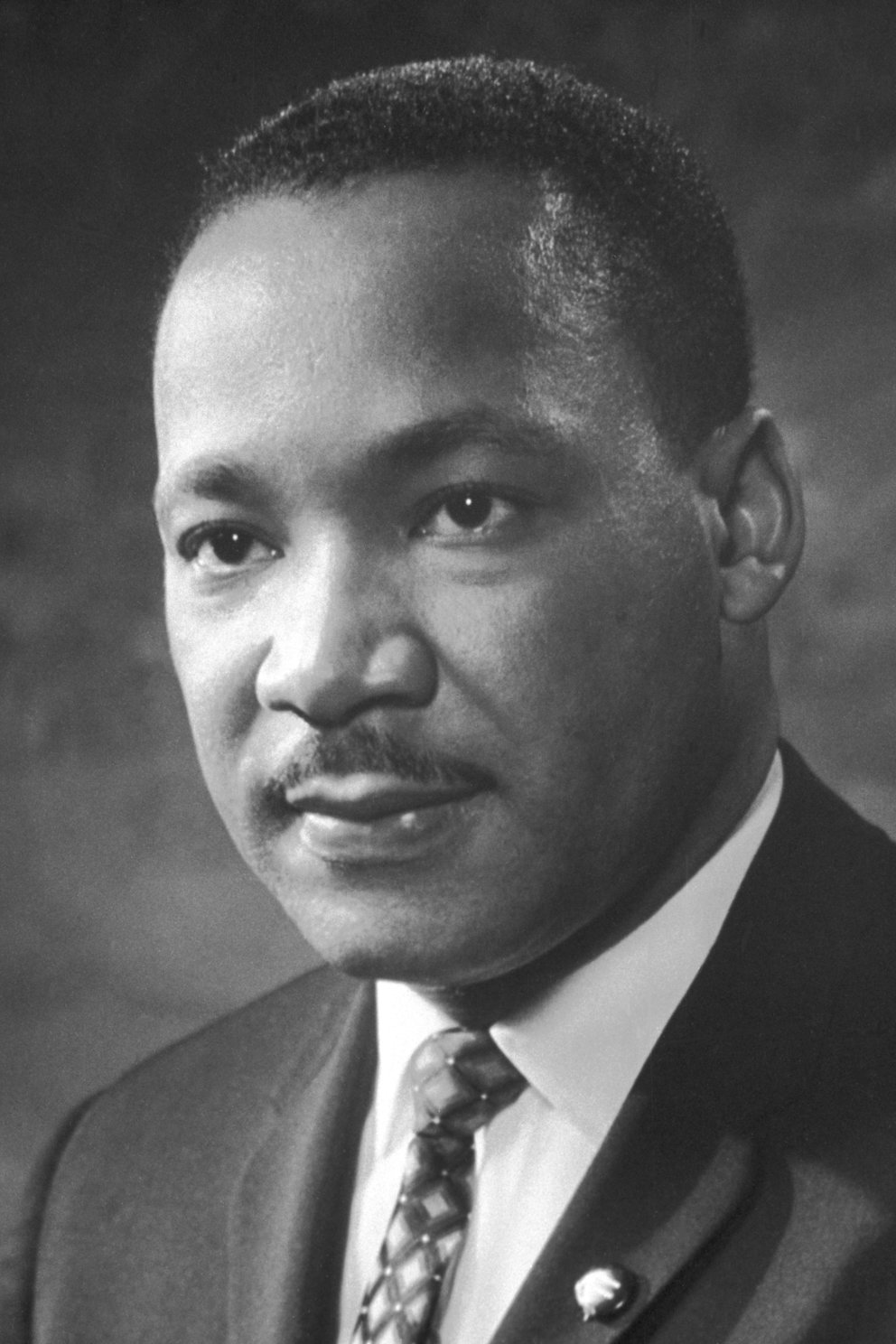

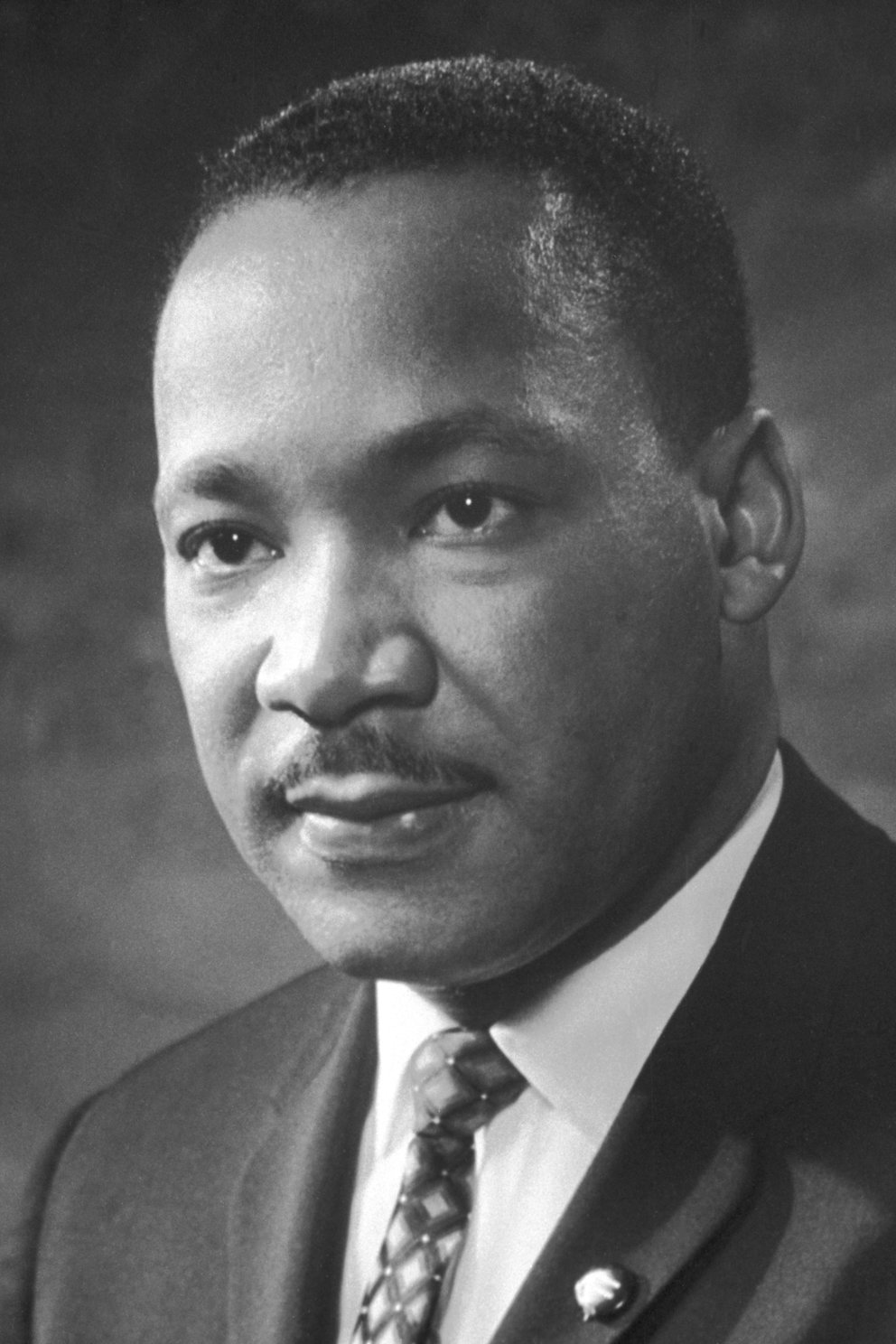

From the early days of the union drive, both King Jr. and King Sr., who were co-pastors at Ebenezer Baptist, voiced their support for the ICWU's efforts and kept up to date on the ongoings at Scripto. The younger King had grown up in the same neighborhood that the plant was in, which was only a few blocks from his house, and many of the employees who were involved in the union drive were church congregants, such as Mary Gurley, who was a leader of the strike and an influential member of the church. King Jr., who by this time was an internationally recognized leader in the civil rights movement, had returned to Atlanta in 1960 to pastor at Ebenezer. At that time, many members of Atlanta's

From the early days of the union drive, both King Jr. and King Sr., who were co-pastors at Ebenezer Baptist, voiced their support for the ICWU's efforts and kept up to date on the ongoings at Scripto. The younger King had grown up in the same neighborhood that the plant was in, which was only a few blocks from his house, and many of the employees who were involved in the union drive were church congregants, such as Mary Gurley, who was a leader of the strike and an influential member of the church. King Jr., who by this time was an internationally recognized leader in the civil rights movement, had returned to Atlanta in 1960 to pastor at Ebenezer. At that time, many members of Atlanta's

Unbeknownst to Levine and others in the union, over the course of several weeks, Singer and King had been in contact with each other and had discussed ways to bring the strike to an end. Singer, who had been unwilling to negotiate with the union, had telephoned King directly to negotiate with him, despite King having no authorization from the ICWU to act as a negotiator. Over the course of several weeks, King and Singer had four meetings at Scripto's headquarters, with very few people on either side being made aware of these meetings. During the discussions, both sides came to an agreement wherein King would have the SCLC end its boycott if the company agreed to give the workers their Christmas bonuses. King may have been willing to accept this agreement in part because he and the SCLC were planning for a campaign in

Unbeknownst to Levine and others in the union, over the course of several weeks, Singer and King had been in contact with each other and had discussed ways to bring the strike to an end. Singer, who had been unwilling to negotiate with the union, had telephoned King directly to negotiate with him, despite King having no authorization from the ICWU to act as a negotiator. Over the course of several weeks, King and Singer had four meetings at Scripto's headquarters, with very few people on either side being made aware of these meetings. During the discussions, both sides came to an agreement wherein King would have the SCLC end its boycott if the company agreed to give the workers their Christmas bonuses. King may have been willing to accept this agreement in part because he and the SCLC were planning for a campaign in

Scripto

Scripto is an American company that was founded in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1924 by Monie A. Ferst. At one time the largest producer of writing instruments in the world, it now produces butane lighters.

History Early years

The company was originall ...

company in Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,71 ...

, United States, held a labor strike

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became common during the I ...

from November 27, 1964, to January 9, 1965. It ended when the company and union agreed to a three-year contract that included wage increases and improved employee benefits. The strike was an important event in the history of the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

, as both civil rights leaders and organized labor activists worked together to support the strike.

Scripto produced writing implements

A writing implement or writing instrument is an object used to produce writing. Writing consists of different figures, lines, and or forms. Most of these items can be also used for other functions such as painting, drawing and technical drawing

...

and lighters

A lighter is a portable device which creates a flame, and can be used to ignite a variety of items, such as cigarettes, gas lighter, fireworks, candles or campfires. It consists of a metal or plastic container filled with a flammable liquid or c ...

in the 1960s. Its main production facility was based in Sweet Auburn

Sweetness is a basic taste most commonly perceived when eating foods rich in sugars. Sweet tastes are generally regarded as pleasurable. In addition to sugars like sucrose, many other chemical compounds are sweet, including aldehydes, ketones, ...

, an African-American neighborhood

African-American neighborhoods or black neighborhoods are types of ethnic enclaves found in many cities in the United States. Generally, an African American neighborhood is one where the majority of the people who live there are African America ...

of Atlanta, and the company's workforce was primarily made up of black women

Black women are women of sub-Saharan African and Afro-diasporic descent, as well as women of Australian Aboriginal and Melanesian descent. The term 'Black' is a racial classification of people, the definition of which has shifted over time and ...

. Since 1940, there had been various attempts to unionize the factory, including an effort by the United Steelworkers

The United Steel, Paper and Forestry, Rubber, Manufacturing, Energy, Allied Industrial and Service Workers International Union, commonly known as the United Steelworkers (USW), is a general trade union with members across North America. Headquar ...

in the 1940s. By and large, unionization efforts were supported by members of Atlanta's black elite and by black church leaders in the area, who believed that a union could help improve the working conditions and wages for the workers. In 1963, the International Chemical Workers Union The International Chemical Workers' Union (ICWU) was a labor union representing workers in the chemical industry in the United States and Canada.

History

The union's origins lay in the Chemical Workers' Council, established by the American Federati ...

(ICWU) was able to unionize the plant. This came during the civil rights movement, and union organizers succeeded in part by tying their union drive to the larger fight for civil rights that was occurring throughout the country and especially in the southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, where the plant was located. Following the unionization, the ICWU sought to secure a labor contract with Scripto, but the company instead challenged the union in court, arguing that the union election had been unfair. After the National Labor Relations Board

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is an independent agency of the federal government of the United States with responsibilities for enforcing U.S. labor law in relation to collective bargaining and unfair labor practices. Under the Nati ...

ruled against the company, they remained reluctant to negotiate with the union, and negotiations continued into November 1964. The main point of contention regarded wage increases, as the union wanted an eight-percent raise across the board while the company pushed for a four-percent wage increase for "skilled" employees and a two-percent raise for "unskilled" employees. The union argued that this was racially discriminatory, as almost all of the factory's white

White is the lightness, lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully diffuse reflection, reflect and scattering, scatter all the ...

employees were considered skilled and nearly all of the African American employees were considered unskilled.

On November 25, the day before Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in the United States, Canada, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Philippines. It is also observed in the Netherlander town of Leiden ...

, many workers gathered and announced plans for a labor strike

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became common during the I ...

. Working over the holiday to prepare picket signs and coordinate logistics, they began their strike on November 27, with about 700 workers performing a walkout

In labor disputes, a walkout is a labor strike, the act of employees collectively leaving the workplace and withholding labor as an act of protest.

A walkout can also mean the act of leaving a place of work, school, a meeting, a company, or an ...

. From the onset, the strike had the support of several civil rights organizations, including the A. Philip Randolph Institute

The A. Philip Randolph Institute (APRI) is an organization for African-American trade unionists. APRI advocates social, labor, and economic change at the state and federal level, using legal and legislative means.

History

In response to the 1963 ...

, Operation Breadbasket, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segreg ...

, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civ ...

(SCLC), the latter of which was led by Martin Luther King Jr. King was an avid supporter of the strike, as many of the strikers were congregants of his Ebenezer Baptist Church, and he helped coordinate a nationwide boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict s ...

of Scripto products. However, as the strike continued, both the union and company remained at an impasse in negotiations, and eventually, King began to negotiate in secret with company president Carl Singer over an agreement to end the strike. After several weeks of discussions, King agreed to call off the boycott if Singer agreed to give the striking employees their Christmas bonuses. This deal, which was made without the knowledge of the union, was announced on December 24 and saw an end to King or the SCLC's involvement in the strike. Union representatives were upset with King's actions, which some historians say may have constitute an unfair labor practice

An unfair labor practice (ULP) in United States labor law refers to certain actions taken by employers or unions that violate the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (49 Stat. 449) (also known as the NLRA and the Wagner Act after NY Senator ...

. However, by this time, the union's strike fund

Strike pay is a payment made by a trade union to workers who are on strike to help in meeting their basic needs while on strike, often out of a special reserve known as a ''strike fund''. Union workers reason that the availability of strike pay inc ...

had been nearly depleted, and without the SCLC's support, they were willing to negotiate a compromise with the company. On January 9, 1965, the union and company signed a three-year labor contract that saw an across-the-board wage increase of $0.04 per hour for every year of the contract. Additionally, workers improved employee benefits, such as additional vacation days and increased pay for working afternoon shifts.

In the aftermath of the strike, King received criticism from many different groups for his involvement, including labor activists and business leaders, and as a result, King and the SCLC refrained from involvement in another major labor dispute until the Memphis sanitation strike

The Memphis sanitation strike began on February 12, 1968, in response to the deaths of sanitation workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker.Estes, S. (2000). `I AM A MAN A MAN?’: Race, Masculinity, and the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike. ''Labor ...

in 1968. Meanwhile, the company and the union developed a better relationship and jointly worked on a replacement to the "skilled"/"unskilled" system that had been at the root of the labor dispute. However, in 1977, with the Sweet Auburn facility considered outdated and the company facing increased competition, Scripto closed the plant and relocated to another facility in the Atlanta metropolitan area. The plant was eventually demolished and today the site is a parking lot for the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park. Discussing the strike in 2018, historian Joseph M. Thompson stated that, while it is primarily viewed by historians in the context of King's involvement and the larger civil rights movement, it also represents a longstanding history of labor organizing among African American women in Atlanta, comparing it to other events such as the 1881 Atlanta washerwomen strike

The Atlanta washerwomen strike of 1881 was a labor strike in Atlanta, Georgia involving African American washerwomen. It began on July 19, 1881, and lasted into August 1881. The strike began as an effort to establish better pay, more respect an ...

and saying, "Within this broader context, the 1964 Scripto strike looks less like a product of the midcentury civil rights movements and more like a victory in the long fight for black women's economic rights in Atlanta".

Background

Scripto

The company now known as Scripto can trace its history back to the establishment of the National Pencil Company inAtlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,71 ...

in 1908. In 1913, a young girl named Mary Phagan

Leo Max Frank (April 17, 1884August 17, 1915) was an American factory superintendent who was convicted in 1913 of the murder of a 13-year-old employee, Mary Phagan, in Atlanta, Georgia. His trial, conviction, and appeals attracted national ...

was found dead in the company's factory, and in the ensuing firestorm that followed, Leo Frank

Leo Max Frank (April 17, 1884August 17, 1915) was an American factory superintendent who was convicted in 1913 of the murder of a 13-year-old employee, Mary Phagan, in Atlanta, Georgia. His trial, conviction, and appeals attracted national at ...

, the factory's superintendent, was lynched

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

. The company's reputation suffered immensely from this series of events, and by the late 1910s, it had declared bankruptcy. However, local businessman Monie Ferst, who was the son-in-law of National Pencil's owner Sigmund Montag, believed that the company's factory on Forsyth Street in downtown Atlanta

Downtown Atlanta is the central business district of Atlanta, Georgia, United States. The larger of the city's two other commercial districts ( Midtown and Buckhead), it is the location of many corporate and regional headquarters; city, county, ...

was still valuable and purchased the company from Montag in 1919, renaming it Atlantic Pen. Ferst was already the owner of M. A. Ferst Ltd., the only manufacturer of pencil lead

A graphite pencil, also called a lead pencil, is a type of pencil in which a thin graphite core is embedded in a shell of other material. The pencil shell is typically wooden, but can be made of plastic or recycled paper.

History

A large deposi ...

in the United States at that time, and Atlantic Pen became a manufacturer of mechanical pencils

A mechanical pencil, also clutch pencil, is a pencil with a replaceable and mechanically extendable solid pigment core called a "lead" . The lead, often made of graphite, is not bonded to the outer casing, and can be mechanically extended as its ...

. The company changed its name to Scripto in the 1920s. In 1931, the company built a new production facility east of downtown. The new plant was located at 425 Houston Street (now known as John Wesley Dobbs

John Wesley Dobbs (March 26, 1882 – August 30, 1961) was an African-American civic and political leader in Atlanta, Georgia. He was often referred to as the unofficial "mayor" of Auburn Avenue, the spine of the black community in the city. ...

Avenue) in Sweet Auburn

Sweetness is a basic taste most commonly perceived when eating foods rich in sugars. Sweet tastes are generally regarded as pleasurable. In addition to sugars like sucrose, many other chemical compounds are sweet, including aldehydes, ketones, ...

, an African-American neighborhood

African-American neighborhoods or black neighborhoods are types of ethnic enclaves found in many cities in the United States. Generally, an African American neighborhood is one where the majority of the people who live there are African America ...

of Atlanta. From the 1930s through the 1960s, Scripto significantly expanded its operations, becoming a manufacturer of not only mechanical pencils, but also of pens

A pen is a common writing instrument that applies ink to a surface, usually paper, for writing or drawing. Early pens such as reed pens, quill pens, dip pens and ruling pens held a small amount of ink on a nib or in a small void or cavity w ...

and lighters

A lighter is a portable device which creates a flame, and can be used to ignite a variety of items, such as cigarettes, gas lighter, fireworks, candles or campfires. It consists of a metal or plastic container filled with a flammable liquid or c ...

. Additionally, from 1951 to 1954, the company operated an ordnance plant that produced artillery shells

A shell, in a military context, is a projectile whose payload contains an explosive, incendiary, or other chemical filling. Originally it was called a bombshell, but "shell" has come to be unambiguous in a military context. Modern usage s ...

for the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is ...

during the Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top: ...

. By the 1960s, Scripto was one of the largest pen manufacturers in the country and one of the largest employers in the city. The company was selling its products internationally and was the world's largest producer of writing implements

A writing implement or writing instrument is an object used to produce writing. Writing consists of different figures, lines, and or forms. Most of these items can be also used for other functions such as painting, drawing and technical drawing

...

.

Unionization efforts in the 1940s and 1950s

Following the company's relocation to Sweet Auburn, Scripto began to recruit employees from the local African American community for low-wage positions. Manyblack women

Black women are women of sub-Saharan African and Afro-diasporic descent, as well as women of Australian Aboriginal and Melanesian descent. The term 'Black' is a racial classification of people, the definition of which has shifted over time and ...

viewed a job at Scripto as preferable to being a domestic worker

A domestic worker or domestic servant is a person who works within the scope of a residence. The term "domestic service" applies to the equivalent occupational category. In traditional English contexts, such a person was said to be "in service ...

for white Americans

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone. This represente ...

, and the company began to employ hundreds of black women at the factory. By 1940, roughly 80 percent of the plant's workforce was made up of African Americans. However, despite the perception of Scripto as a better employer than other options in the city, workplace discrimination

Employment discrimination is a form of illegal discrimination in the workplace based on legally protected characteristics. In the U.S., federal anti-discrimination law prohibits discrimination by employers against employees based on age, race, ...

against African American workers there was still persistent, and the company's management was still made up entirely of white people. In light of these issues, starting in the 1940s, there were several unionization efforts among the plant employees. In 1940, the United Steelworkers

The United Steel, Paper and Forestry, Rubber, Manufacturing, Energy, Allied Industrial and Service Workers International Union, commonly known as the United Steelworkers (USW), is a general trade union with members across North America. Headquar ...

(USW) became the first labor union to attempt to organize the Scripto workers. Their efforts ultimately failed, with union organizers accusing the few white employees who worked in the factory of undermining support for the union.

In 1946, the USW again tried to organize a union at the Scripto plant, and following a union vote, they began to officially represent the workers in February of that year. The USW's success was due in large part to support from local

In 1946, the USW again tried to organize a union at the Scripto plant, and following a union vote, they began to officially represent the workers in February of that year. The USW's success was due in large part to support from local black church

The black church (sometimes termed Black Christianity or African American Christianity) is the faith and body of Christian congregations and denominations in the United States that minister predominantly to African Americans, as well as thei ...

leaders in the area, such as Martin Luther King Sr.

Martin Luther King (born Michael King; December 19, 1899November 11, 1984) was an African-American Baptist pastor, missionary, and an early figure in the Civil Rights Movement. He was the father and namesake of the civil rights leader Martin Lut ...

King's church, Ebenezer Baptist Church, was located only a few blocks from the Scripto plant, and many of the Scripto employees were congregants of the church. USW official W. H. Crawford later wrote to King to express his gratitude, saying that King's support of the unionization effort resulted in its success. However, Scripto disputed the results of the union election and refused to collectively bargain

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and rights for workers. The i ...

with the union. As a result, the USW called for a strike on October 7, and over 500 of the company's 600 African American workers took part in picketing

Picketing is a form of protest in which people (called pickets or picketers) congregate outside a place of work or location where an event is taking place. Often, this is done in an attempt to dissuade others from going in (" crossing the pic ...

. The union's demands included a union contract, increased wages, paid vacations, and eight-hour shifts. The strike lasted for about six months, during which time the strikers were subjected to harassment from members of the Atlanta Police Department

The Atlanta Police Department (APD) is a law enforcement agency in the city of Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.

The city shifted from its rural-based Marshal and Deputy Marshal model at the end of the 19th century. In 1873, the department was formed with 2 ...

, which at the time included known members of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Ca ...

. However, on March 22, 1947, with little to no progress made on achieving their goals, the USW called off the strike. Of the 400 workers who had remained on strike until the end, only 19 were rehired by Scripto, prompting the USW to file charges against the company with the National Labor Relations Board

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is an independent agency of the federal government of the United States with responsibilities for enforcing U.S. labor law in relation to collective bargaining and unfair labor practices. Under the Nati ...

(NLRB), though the board later found the company free of any legal wrongdoing.

In 1947, following the end of the USW strike, local businessman and former politician James V. Carmichael

James Vinson Carmichael (October 2, 1910 – November 28, 1972) was member of the Georgia General Assembly, an attorney, business executive, and candidate for Governor of Georgia.

Early life

Carmichael was born, in Cobb County, Georgia to parent ...

became the president of Scripto. As a politician, Carmichael had served in the Georgia General Assembly

The Georgia General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is bicameral, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives.

Each of the General Assembly's 236 members serve two-year terms and are directly ...

in the 1930s and was a candidate in the 1946 Georgia gubernatorial election

The 1946 Georgia gubernatorial election took place on November 5, 1946, in order to elect the Governor of Georgia.

Incumbent Democratic Governor Ellis Arnall was term-limited, and ineligible to run for a second term.

As was common at the time, ...

against Eugene Talmadge

Eugene Talmadge (September 23, 1884 – December 21, 1946) was an attorney and American politician who served three terms as the 67th governor of Georgia, from 1933 to 1937, and then again from 1941 to 1943. Elected to a fourth term in November ...

. Despite winning a plurality

Plurality may refer to:

Voting

* Plurality (voting), or relative majority, when a given candidate receives more votes than any other but still fewer than half of the total

** Plurality voting, system in which each voter votes for one candidate and ...

of votes, Carmichael lost the election to Talmadge due to Georgia's county unit system

The county unit system was a voting system used by the U.S. state of Georgia to determine a victor in statewide primary elections from 1917 until 1962.

History

Though the county unit system had informally been used since 1898, it was formally enac ...

that was used in elections. As a businessman, Carmichael is known for his role in aircraft manufacturing

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines ...

, as he was an assistant general manager of the Bell Bomber Plant in Marietta, Georgia

Marietta is a city in and the county seat of Cobb County, Georgia, United States. At the 2020 census, the city had a population of 60,972. The 2019 estimate was 60,867, making it one of Atlanta's largest suburbs. Marietta is the fourth largest ...

, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and later convinced the Lockheed Corporation

The Lockheed Corporation was an American aerospace manufacturer. Lockheed was founded in 1926 and later merged with Martin Marietta to form Lockheed Martin in 1995. Its founder, Allan Lockheed, had earlier founded the similarly named but ...

to locate a plant in the city. He viewed himself as a benevolent employer and took a paternalistic

Paternalism is action that limits a person's or group's liberty or autonomy and is intended to promote their own good. Paternalism can also imply that the behavior is against or regardless of the will of a person, or also that the behavior expres ...

approach to management. In 1952, before a speech at his alma mater of Emory University

Emory University is a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1836 as "Emory College" by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory, Emory is the second-oldest private institution of h ...

, he stated that workers had been exploited by business owners in the past and that unionization was one way that workers attempted to fight back against those abuses but also criticized workers for "blindly" following union leaders and advocated instead for an "enlightened management" that would eliminate the need for unions altogether. On issues regarding race, Carmichael was viewed as either a moderate, and in the 1946 election, he openly criticized Talmadge, a white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

, calling his previous administration a "ranting dictatorship" and saying, "No one is going to invest money in industry when you have in the governor’s office a man who is continually stirring up race and class hatred and creating unrest in labor’s ranks". Additionally, Carmichael took pride in Scripto's hiring policies, as it was one of the first companies in the city to employ African Americans in production roles. During the 1950s, when Sweet Auburn was experiencing an economic downturn, Scripto was one of the few companies to continue to grow. During this same time, Carmichael turned down several offers to relocate the plant outside of the city, and company executives made it a point to continue to hire black women. However, during a unionization effort at the company's ordnance plant in 1953, Carmichael fired several of the workers who were involved before the plant shut down the following year.

ICWU unionization

In late 1962, theInternational Chemical Workers Union The International Chemical Workers' Union (ICWU) was a labor union representing workers in the chemical industry in the United States and Canada.

History

The union's origins lay in the Chemical Workers' Council, established by the American Federati ...

(ICWU), an AFL–CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL–CIO) is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 56 national and international unions, together representing more than 12 million ac ...

-affiliated union that had had recent success in organizing smaller production facilities in the Atlanta metropolitan area, began a union drive at Scripto. The ICWU believed that the organization effort would be difficult, as the plant's overwhelmingly majority workforce of black women constituted a demographic that the union felt was not typically responsive to organized labor efforts. In an attempt to win support, the ICWU ensured that the drive focused not only on traditional labor activism topics but also on civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

. The union called on James Hampton, an African American labor activist and Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christianity, Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe ...

preacher, to go to Atlanta and help with their organizing efforts. In discussions with the workers, Hampton compared his own work in labor organizing to the work of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., drawing a connection between the ICWU's organizing efforts and the activities of the nationwide civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

. 1963 had been a momentous year for the civil rights movement, as many landmark events had taken place around the time that the ICWU was organizing the Scripto workers, including the Birmingham campaign

The Birmingham campaign, also known as the Birmingham movement or Birmingham confrontation, was an American movement organized in early 1963 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to bring attention to the integration efforts o ...

in nearby Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

, the Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

The Stand in the Schoolhouse Door took place at Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963. George Wallace, the Governor of Alabama, in a symbolic attempt to keep his inaugural promise of "George Wallace's 1963 Inaugural A ...

following the desegregation

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact o ...

of the University of Alabama

The University of Alabama (informally known as Alabama, UA, or Bama) is a public research university in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Established in 1820 and opened to students in 1831, the University of Alabama is the oldest and largest of the publi ...

, and the assassination of NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

field secretary Medgar Evers

Medgar Wiley Evers (; July 2, 1925June 12, 1963) was an American civil rights activist and the NAACP's first field secretary in Mississippi, who was murdered by Byron De La Beckwith. Evers, a decorated U.S. Army combat veteran who had served ...

in Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Mis ...

. Hampton also worked with black church leaders in Atlanta, such as King Sr., to get their support for the strike. Hampton was overall successful in getting African American clergy to support the ICWU's efforts, though one notable exception was William Holmes Borders Rev. William Holmes Borders, Sr (24 February 1905 – 23 November 1993) was a civil rights activist and leader and pastor of Wheat Street Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia from 1937 to 1988.

Borders' influence in the black community was the trigge ...

, the pastor of Wheat Street Baptist Church, who declined to support the union drive because of his personal friendship with Carmichael.

By August 1963, the ICWU had obtained enough authorization cards that they could petition for an NLRB election. The company agreed to an election in late September. In the meantime, hoping to prevent a successful union vote, the company instituted several changes, including the formation of an employee committee and the removal of racial segregation signs from the plant's bathrooms and water fountains. In the ensuing six weeks, the union focused on building

By August 1963, the ICWU had obtained enough authorization cards that they could petition for an NLRB election. The company agreed to an election in late September. In the meantime, hoping to prevent a successful union vote, the company instituted several changes, including the formation of an employee committee and the removal of racial segregation signs from the plant's bathrooms and water fountains. In the ensuing six weeks, the union focused on building solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dicti ...

among the employees and assuaging fears over company reprisals against those involved in the union efforts, while the company focused on appealing to the goodwill that they felt they had fostered with longtime employees. On September 11, about two weeks before the vote was scheduled to take place, Carmichael gathered about 1,000 employees and gave a speech wherein he highlighted his progressive stance on race and urged the employees to vote against unionization, saying in part that "a vote for the union ould be Ould is an English surname and an Arabic name ( ar, ولد). In some Arabic dialects, particularly Hassaniya Arabic, ولد (the patronymic, meaning "son of") is transliterated as Ould. Most Mauritanians have patronymic surnames.

Notable p ...

a slap in the face of one of the truest friends the Negro

In the English language, ''negro'' is a term historically used to denote persons considered to be of Black African heritage. The word ''negro'' means the color black in both Spanish and in Portuguese, where English took it from. The term can be ...

ever had in Georgia or in the entire South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

". However, to many workers, support for the union drive was tied to the civil rights movement, and in the weeks leading up to the vote, other notable events, such as King Jr.'s " I Have a Dream" at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing

The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing was a white supremacist terrorist bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on Sunday, September 15, 1963. Four members of a local Ku Klux Klan chapter planted 19 sticks of dynam ...

in Birmingham, Alabama

Birmingham ( ) is a city in the north central region of the U.S. state of Alabama. Birmingham is the seat of Jefferson County, Alabama's most populous county. As of the 2021 census estimates, Birmingham had a population of 197,575, down 1% fr ...

, contributed to an atmosphere of heightened racial partisanship among the workers. On September 27, the election was held, and of the 1,005 employees who were eligible to vote, 953, or approximately 95 percent, did. Of these 1,005, 855 were African American. In a 519–428 result, the union won and became the official representative of the workers. Scripto employees were grouped under the local union

A local union (often shortened to local), in North America, or union branch (known as a lodge in some unions), in the United Kingdom and other countries, is a local branch (or chapter) of a usually national trade union. The terms used for sub-bran ...

of ICWU Local 754, which was made up almost entirely of black women.

A week after the election had taken place, Thomas C. Shelton of the Atlanta-based law firm

A law firm is a business entity formed by one or more lawyers to engage in the practice of law. The primary service rendered by a law firm is to advise clients (individuals or corporations) about their legal rights and responsibilities, and to ...

Kilpatrick, Cody, Rogers, McClatchey & Regenstein, Scripto's legal counsel

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solicitor ...

, filed objections with the NLRB, arguing that the union's use of racial rhetoric and drawing connections to the larger civil rights movement had caused the "sober, informed exercise of the employees' vote" to be impossible, rendering the election null. While the Regional Director of the NLRB rejected the objection, Shelton continued to argue that the results of the election was unfair, citing previous NLRB rulings regarding the use of race-related issues in influencing union votes. For instance, in 1962, the NLRB ruled in an election involving the Sewell Manufacturing Company that "appeals to racial prejudice in matters unrelated to the election issues ... have no place in Board electoral campaigns". Additionally, in a 1957 case involving the Westinghouse Electric Corporation

The Westinghouse Electric Corporation was an American manufacturing company founded in 1886 by George Westinghouse. It was originally named "Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company" and was renamed "Westinghouse Electric Corporation" i ...

, the NLRB stated that "the consequences of injecting the racial issue where racial prejudices are likely to exist is to pit race against race and thereby distort a clear expression of choice on the issue of unionism". Shelton also argued that the characterization of Carmichael and Scripto by the union was unfair and inaccurate and collected testimony from several prominent individuals that highlighted Carmichael's and the company's stance on race. Benjamin Mays

Benjamin Elijah Mays (August 1, 1894 – March 28, 1984) was an American Baptist minister and American rights leader who is credited with laying the intellectual foundations of the American Civil rights movement (1896–1954), civil rights movem ...

, president of Morehouse College

, mottoeng = And there was light (literal translation of Latin itself translated from Hebrew: "And light was made")

, type = Private historically black men's liberal arts college

, academic_affiliation ...

and a longtime friend of Carmichael, spoke positively of his positions on racial issues, while former mayor of Atlanta

Here is a list of mayors of Atlanta, Georgia. The mayor is the highest elected official in Atlanta. Since its incorporation in 1847, the city has had 61 mayors. The current mayor is Andre Dickens who was elected in the 2021 election and took o ...

William B. Hartsfield

William Berry Hartsfield Sr. (March 1, 1890 – February 22, 1971), was an American politician who served as the 49th and 51st Mayor of Atlanta, Georgia. His tenure extended from 1937 to 1941 and again from 1942 to 1962, making him the longest-s ...

said that Scripto was well known for their progressive stance on hiring African Americans. Finally, on June 9, 1964, after about ten months of petitioning, the NLRB denied Shelton's requests and awarded the ICWU a certificate of representation for Scripto.

Contract negotiations

Despite the NLRB's awarding of a certificate of representation, the ICWU expressed dismay over the negotiations they were having with the company over the terms of a newlabor contract

An employment contract or contract of employment is a kind of contract used in labour law to attribute rights and responsibilities between parties to a bargain.

The contract is between an "employee" and an "employer". It has arisen out of the old ...

. Jerry Levine, a labor activist from New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

who had joined the ICWU in October 1963, served as the representative for the ICWU in their negotiations with Scripto. Levine said that the contract negotiations lasted for about six months, during which time he said the company was "going through the motions" of bargaining in good faith

In human interactions, good faith ( la, bona fides) is a sincere intention to be fair, open, and honest, regardless of the outcome of the interaction. Some Latin phrases have lost their literal meaning over centuries, but that is not the case ...

, often spending weeks at a time discussing the contents of a couple of paragraphs. Additionally, important issues such as wages and other economic policies were not being addressed. As the negotiations continued, Levine began to believe that strike action

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Labor (economics), work. A strike usually takes place in response to grievance (labour), employee grievance ...

was the only way to convince the company to agree to a contract, and while negotiations were ongoing, the union sought to strengthen its ties and increase support in the local community. Also during this time, Carmichael had been removed from his position of president by Ferst and placed in the ceremonial role of chairman. The move came due to Carmichael's poor health and a steady decline in Scripto's sales. For two years leading up to 1964, Scripto had had declining profits, which were attributed to labor costs and increased competition. In his new role, Carmichael was not involved in the contract negotiations and functioned mostly as a spokesperson

A spokesperson, spokesman, or spokeswoman, is someone engaged or elected to speak on behalf of others.

Duties and function

In the present media-sensitive world, many organizations are increasingly likely to employ professionals who have receiv ...

for the brand. Carl Singer, a businessman who had previously worked in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

for the Sealy Mattress Company

Sealy (formerly the Sealy Corporation) is an American brand of mattresses marketed and sold by Tempur Sealy International. It draws its name from the city where the Sealy Corporation originally started, Sealy, Texas, United States.

History

In ...

, was brought in to replace Carmichael as Scripto's president and chief executive officer

A chief executive officer (CEO), also known as a central executive officer (CEO), chief administrator officer (CAO) or just chief executive (CE), is one of a number of corporate executives charged with the management of an organization especial ...

. At the time, Singer was aware that there were contract negotiations, but was not made aware of the issues the company was having with the union. This corporate shakeup was kept private from the general public.

By November 1964, the company's proposal to the union would have seen a four-percent wage increase for workers categorized as "skilled" and two-percent wage increases for "unskilled" workers. At the time, unskilled workers at the factory were earning between $1.25 and $1.30 per hour, and the two-percent wage increase would have amounted to about $0.03 more per hour. The union rebuffed with a proposal of an eight-percent wage increase across the board. The union also alleged that the company's proposed wage increase was not an actual pay increase, as the company was planning to offer the raises at the expense of its Christmas bonus

A thirteenth salary, or end-of-year bonus, is an extra payment given to employees at the end of December. Although the amount of the payment depends on a number of factors, it usually matches an employee's monthly salary and can be paid in ...

es, which often amounted to about a week's pay. Additionally, the union called the company's proposal discriminatory, as only six African American workers at Scripto were considered skilled. The remainder of the company's skilled employees were white, while the rest of the African American employees were classified as unskilled. At the time, Scripto had about 700 African American employees, most of whom were women, and about 200 white workers. On average, these unskilled workers at Scripto earned $400 below the national poverty threshold

The poverty threshold, poverty limit, poverty line or breadline is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country. The poverty line is usually calculated by estimating the total cost of one year's worth of necessities for t ...

.

Move toward strike action

On November 25, 1964, the day beforeThanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in the United States, Canada, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Philippines. It is also observed in the Netherlander town of Leiden ...

, workers constituting almost the entirety of the first shift met at the ICWU union hall on Edgewood Avenue

Edgewood Avenue is a street in Atlanta, Georgia, United States which runs from Five Points in Downtown Atlanta, eastward through the Old Fourth Ward. The avenue runs in the direction of the Edgewood neighborhood, and stops just short of it ...

, near the factory, and demanded that a strike be commenced. The action caught Levine off guard, and he was unsure what had prompted the sudden movement, though he speculated that it stemmed from disappointment from the workers' bargaining unit

A bargaining unit, in labor relations, is a group of employees with a clear and identifiable community of interests who is (under US law) represented by a single labor union in collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negot ...

that had spread to the rank-and-file employees. While Levine felt that the timing was not right for the strike, he nonetheless acquiesced to the workers' demands, and they began to prepare for a strike. The employees worked over the holiday in order to have picket sign

Picketing is a form of protest in which people (called pickets or picketers) congregate outside a place of work or location where an event is taking place. Often, this is done in an attempt to dissuade others from going in (" crossing the pic ...

s made for when the plant reopened on November 27, the day after Thanksgiving. Company executives who were on holiday vacations were alerted to the strike preparations, and many returned to Atlanta early.

Course of the strike

Early strike activities

The strike began on November 27, 1964, the day after Thanksgiving, with awalkout

In labor disputes, a walkout is a labor strike, the act of employees collectively leaving the workplace and withholding labor as an act of protest.

A walkout can also mean the act of leaving a place of work, school, a meeting, a company, or an ...

. Approximately 85 percent of the plant's workforce participated in the strike, made up primarily of about 700 black women. However, 117 skilled workers, which included six black men, did not participate in the strike. Under Georgia's right-to-work law

In the context of labor law in the United States, the term "right-to-work laws" refers to state laws that prohibit union security agreements between employers and labor unions which require employees who are not union members to contribute t ...

s, the plant remained open during the strike, and according to the plant's general manager

A general manager (GM) is an executive who has overall responsibility for managing both the revenue and cost elements of a company's income statement, known as profit & loss (P&L) responsibility. A general manager usually oversees most or all ...

, the factory was continuing to operate under its three-shift schedule without interruption. Outside the plant, the striking employees carried picket signs with slogans such as "We're Human Beings — Not Machines" and "We Won't Be Slaves No More" and sang protest song

A protest song is a song that is associated with a movement for social change and hence part of the broader category of ''topical'' songs (or songs connected to current events). It may be folk, classical, or commercial in genre.

Among social mov ...

s including "We Shall Not Be Moved

"I Shall Not Be Moved", also known as "We Shall Not Be Moved", is an African-American slave spiritual, hymn, and protest song dating to the early 19th century American south. It was likely originally sung at revivalist camp-meetings as a slave ...

" and "We Shall Overcome

"We Shall Overcome" is a gospel song which became a protest song and a key anthem of the American civil rights movement. The song is most commonly attributed as being lyrically descended from "I'll Overcome Some Day", a hymn by Charles Albert ...

". In the first week of the strike, the ''Atlanta Daily World

The ''Atlanta Daily World'' is the oldest black newspaper in Atlanta, Georgia, founded in 1928. Currently owned by Real Times Inc., it publishes daily online.

It was "one of the earliest and most influential black newspapers."

History Establ ...

'', the city's African-American newspaper

African-American newspapers (also known as the Black press or Black newspapers) are news publications in the United States serving African-American communities. Samuel Cornish and John Brown Russwurm started the first African-American periodi ...

, reported on the strike with front-page coverage. National news agencies

A news agency is an organization that gathers news reports and sells them to subscribing news organizations, such as newspapers, magazines and radio and television broadcasters. A news agency may also be referred to as a wire service, newswi ...

also covered the strike, with their reporting focusing primarily on the racial issues at play. Through the course of the strike, Scripto hired replacement workers to keep the plant running, and they placed "Help Wanted" advertisements in many local newspapers, including the ''Daily World'', which prompted controversy among the paper's primarily black readership. Meanwhile, strikers received a weekly strike pay

Strike pay is a payment made by a trade union to workers who are on strike to help in meeting their basic needs while on strike, often out of a special reserve known as a ''strike fund''. Union workers reason that the availability of strike pay ...

of $57 from the union, in addition to fringe benefits

Employee benefits and (especially in British English) benefits in kind (also called fringe benefits, perquisites, or perks) include various types of non-wage compensation provided to employees in addition to their normal wages or salaries. Inst ...

. The ICWU did not initially have the provisions in place to fund the strike, and for the first two weeks, Levine met with local labor leaders and activist groups to help fund the strike. While labor leaders were largely supportive of the strike and offered financial support, rank-and-file union members were less supportive.

Initial attempts at mediation

A week after the strike began, representatives from the union and the company met with William S. Bradford, amediator

Mediator may refer to:

*A person who engages in mediation

* Business mediator, a mediator in business

*Vanishing mediator, a philosophical concept

*Mediator variable, in statistics

Chemistry and biology

* Mediator (coactivator), a multiprotein ...

for the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, to attempt to resolve their issues. The main point of discussion in the meetings regarded the differences in pay increases between unskilled and skilled employees. The union viewed the issue as a racial one, as the company's proposal would have resulted in a vast majority of the African American workforce receiving a substantially lower raise than their white counterparts. Additionally, the union alleged that a reason for this was that the company did not offer training to African Americans that would have allowed them to be classified as skilled workers. The company rejected the union's view that the matter was primarily racial and instead argued that the dispute was a purely economic one. Throughout the strike, the company continued to downplay the racial aspect of the labor dispute. During these mediation sessions, both sides held to the same pay raise proposals that they had made before the strike. Additionally, the company's proposal would not have seen workers' union dues

Union dues are a regular payment of money made by members of unions. Dues are the cost of membership; they are used to fund the various activities which the union engages in. Nearly all unions require their members to pay dues.

Variation

Many ...

withheld from their paychecks. As a result, during the first few weeks of the strike, the two sides remained at an impasse in negotiations.

Involvement of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

From the early days of the union drive, both King Jr. and King Sr., who were co-pastors at Ebenezer Baptist, voiced their support for the ICWU's efforts and kept up to date on the ongoings at Scripto. The younger King had grown up in the same neighborhood that the plant was in, which was only a few blocks from his house, and many of the employees who were involved in the union drive were church congregants, such as Mary Gurley, who was a leader of the strike and an influential member of the church. King Jr., who by this time was an internationally recognized leader in the civil rights movement, had returned to Atlanta in 1960 to pastor at Ebenezer. At that time, many members of Atlanta's

From the early days of the union drive, both King Jr. and King Sr., who were co-pastors at Ebenezer Baptist, voiced their support for the ICWU's efforts and kept up to date on the ongoings at Scripto. The younger King had grown up in the same neighborhood that the plant was in, which was only a few blocks from his house, and many of the employees who were involved in the union drive were church congregants, such as Mary Gurley, who was a leader of the strike and an influential member of the church. King Jr., who by this time was an internationally recognized leader in the civil rights movement, had returned to Atlanta in 1960 to pastor at Ebenezer. At that time, many members of Atlanta's black elite

The Black elite is any elite, either political or economic in nature, that is made up of people who identify as of Black African descent. In the Western World, it is typically distinct from other national elites, such as the United Kingdom's aris ...

, which included Jesse Hill

Jesse Hill Jr. (May 30, 1926 – December 17, 2012) was an African American civil rights activist. He was active in the civic and business communities of the city for more than five decades. Hill was president and chief executive officer of the A ...

, Samuel Woodrow Williams

Samuel Woodrow Williams was a Baptist minister, professor of philosophy and religion, and Civil Rights activist. Williams was born on February 12, 1912, in Sparkman (Dallas County) then grew up in Chicot County, Arkansas. An African American, ...

, and the younger King's father, among others, did not want to see him engage in the same type of high-profile activism that he had been involved in elsewhere. The city's African American power brokers had spent years crafting agreements with the city's white power structure for racial progress, and many were fearful that the younger King's actions could jeopardize the status quo. While the younger King had kept a primarily low-profile during most of his time in Atlanta, he nonetheless engaged in civil rights activism within the city, such as his involvement in the Atlanta sit-ins

The Atlanta sit-ins were a series of sit-ins that took place in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Occurring during the sit-in movement of the larger civil rights movement, the sit-ins were organized by the Committee on Appeal for Human Right ...

in 1960. Early in the strike, ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

'' reported that the younger King was among several prominent African American leaders who supported the strike.

On November 29, the younger King, acting in his role as the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civ ...

(SCLC), an Atlanta-based civil rights organization whose headquarters were only a few blocks from the plant, sent a telegram to Carmichael wherein he expressed his support for the strikers, criticized the company for being anti-union

Union busting is a range of activities undertaken to disrupt or prevent the formation of trade unions or their attempts to grow their membership in a workplace.

Union busting tactics can refer to both legal and illegal activities, and can range ...

and racially discriminatory, and said that he would call for a boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict s ...

of Scripto products if the strike persisted. On December 1, King was scheduled to speak to a large group of strikers at a rally held across the street from the factory, but he was unable to attend the meeting due to a meeting he had with Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

that same day in Washington, D.C. The Reverend C. T. Vivian

Cordy Tindell Vivian (July 30, 1924July 17, 2020) was an American minister, author, and close friend and lieutenant of Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights movement. Vivian resided in Atlanta, Georgia, and founded the C. T. Vivian Leade ...

, who had moved to Atlanta in 1963 to become an executive in the SCLC, took his place, while other speakers included the Reverend Joseph E. Boone

Joseph Everhart Boone (September 19, 1922 – July 15, 2006) was an American civil rights activist and organizer who marched together with Martin Luther King Jr.

Biography

Joseph E. Boone was the son of John L. and Mattie Roberts Boone.

He at ...

, Georgia State Senator

The Georgia State Senate is the upper house of the Georgia General Assembly, in the U.S. state of Georgia.

Legal provisions

The Georgia State Senate is the upper house of the Georgia General Assembly, with the lower house being the Georgia H ...

Leroy Johnson, and union negotiator Phil Whitehead. SCLC executive Ralph Abernathy

Ralph David Abernathy Sr. (March 11, 1926 – April 17, 1990) was an American civil rights activist and Baptist minister. He was ordained in the Baptist tradition in 1948. As a leader of the civil rights movement, he was a close friend and ...

also became involved in the strike effort at this time and participated in picketing with protesting workers.

Vivian had been the primary voice within the SCLC for supporting the strike, as he viewed unions as a way for African Americans to attain economic equality

Equity, or economic equality, is the concept or idea of fairness in economics, particularly in regard to taxation or welfare economics. More specifically, it may refer to a movement that strives to provide equal life chances regardless of identit ...

based on his previous work experience in civil rights organizing in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Roc ...

. By contrast, King's view of organized labor was more mixed. While he was a vocal advocate for economic justice

Justice in economics is a subcategory of welfare economics. It is a "set of moral and ethical principles for building economic institutions". Economic justice aims to create opportunities for every person to have a dignified, productive and creativ ...

and often solicited unions for financial support, he was also often critical of unions as hindrances to economic mobility for African Americans, as many unions in the United States at the time discriminated against black people and barred them from membership. Additionally, while some unions had supported King's March on Washington the previous year, the AFL–CIO did not, and many of their associated unions were not active in organizing workers in the southern United States. Overall, most of the support for the strike from black clergy and civil rights leaders in the city stemmed less from their support for organized labor and more from the fact that many of the strikers were members of their congregations. However, in a December 4 television interview, King stated, "We have decided that now is the time to identify our movement very closely with labor". While Vivian viewed the strike as a way to strengthen the bond between organized labor and the civil rights movement, SCLC executive Hosea Williams

Hosea Lorenzo Williams (January 5, 1926 – November 16, 2000) was an American civil rights leader, activist, ordained minister, businessman, philanthropist, scientist, and politician. He is best known as a trusted member of fellow famed civil ...

saw the strike as a way for King to buck the local black leadership and lead a demonstration in Atlanta, which was viewed as a major center for African American culture in the United States.

On December 4, King left Atlanta to travel to Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

to accept the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

. He spent about two weeks traveling during this time, including to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, New York City, and Washington, D.C., before returning to Atlanta on December 18. The next day, within 24 hours of returning, King marched in a picket line with several other protestors, including a union representative from the ICWU's international headquarters in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

. Coming so soon after his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance, the action helped to bring international attention to the strike. The following day, on December 20, King spoke to about 250 striking employees at a rally at Ebenezer Baptist. During the speech, he reiterated the SCLC's support for the strike and stressed the interconnectedness of the labor movement and the civil rights movement, saying, "Along with the struggle to desegregate, we must engage in the struggle for better jobs". Throughout the strike, King's involvement was highly criticized by many conservative groups. Local businessman and politician Lester Maddox

Lester Garfield Maddox Sr. (September 30, 1915 – June 25, 2003) was an American politician who served as the 75th governor of the U.S. state of Georgia from 1967 to 1971. A populist Democrat, Maddox came to prominence as a staunch segregati ...

placed an advertisement in ''The Atlanta Journal

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the only major daily newspaper in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the result of the merger between ...

'' that called King and the SCLC activists "Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

inspired racial agitators", while Calvin Craig, a grand dragon

Ku Klux Klan (KKK) nomenclature has evolved over the order's nearly 160 years of existence. The titles and designations were first laid out in the original Klan's prescripts of 1867 and 1868, then revamped with William J. Simmons's '' Kloran'' of ...

of the United Klans of America

The United Klans of America Inc. (UKA), based in Alabama, is a Ku Klux Klan organization active in the United States. Led by Robert Shelton, the UKA peaked in membership in the late 1960s and 1970s,Abby Ferber. '' White Man Falling: Race, Gender, ...

, said that King was "overstepping the bounds of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

" by getting involved in the strike.

Boycott

One of the biggest contributions that the SCLC had to the strike effort was in organizing a national boycott of Scripto products as a way to apply pressure to Scripto. Vivian contacted 2,500 SCLC affiliates to inform them of the boycott, and the organization made requests to merchants to remove Scripto displays from their stores. In addition, several other civil rights and labor organizations supported the boycott, including theStudent Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segreg ...

(SNCC), the A. Philip Randolph Institute

The A. Philip Randolph Institute (APRI) is an organization for African-American trade unionists. APRI advocates social, labor, and economic change at the state and federal level, using legal and legislative means.

History

In response to the 1963 ...

, Operation Breadbasket, and the Atlanta Labor Council. Over 500,000 leaflets were printed and distributed to local unions across the United States asking them to respect the boycott. These leaflets featured a crying Santa Claus

Santa Claus, also known as Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Kris Kringle, or simply Santa, is a legendary figure originating in Western Christian culture who is said to bring children gifts during the late evening and overnigh ...

with a printed message reading, "Don't buy Scripto products". John Lewis

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American politician and civil rights activist who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960 Nashvill ...

, the chairman of the SNCC, wrote a letter to the General Services Administration

The General Services Administration (GSA) is an independent agency of the United States government established in 1949 to help manage and support the basic functioning of federal agencies. GSA supplies products and communications for U.S. gove ...

(an independent agency of the United States government

Independent agencies of the United States federal government are agencies that exist outside the federal executive departments (those headed by a Cabinet secretary) and the Executive Office of the President. In a narrower sense, the term refers ...

) urging them to also honor the boycott. At the time, Scripto held two contracts with the federal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

, and Lewis stated in his letter that Scripto had been able to underbid other manufacturers for these contracts by engaging in "economic slavery

Wage slavery or slave wages refers to a person's dependence on wages (or a salary) for their livelihood, especially when wages are low, treatment and conditions are poor, and there are few chances of upward mobility.

The term is often used ...

" with their African American workers. The GSA responded that they would investigate the matter, specifically concerning whether Scripto was in violation of Executive Order 10925

Executive Order 10925, signed by President John F. Kennedy on March 6, 1961, required government contractors to "take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed and that employees are treated during employment without regard to thei ...

, which mandated equal opportunity

Equal opportunity is a state of fairness in which individuals are treated similarly, unhampered by artificial barriers, prejudices, or preferences, except when particular distinctions can be explicitly justified. The intent is that the important ...

in the workforce. However, nothing came of this investigation by the time the boycott ended.

Negotiations between Singer and King and the end of the strike