1946 Romanian Legislative Election on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

General elections were held in

General elections were held in

General elections were held in

General elections were held in Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

on 19 November 1946, in the aftermath of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. The official results gave a victory to the Romanian Communist Party

The Romanian Communist Party ( ro, Partidul Comunist Român, , PCR) was a communist party in Romania. The successor to the pro-Bolshevik wing of the Socialist Party of Romania, it gave ideological endorsement to a communist revolution that wou ...

(PCR), its allies inside the Bloc of Democratic Parties (''Blocul Partidelor Democrate'', BPD), together with its associates, the Hungarian People's Union (UPM or MNSZ) and the Democratic Peasants' Party–Lupu.Ștefan, p. 9; Tismăneanu, p. 323 The event marked a decisive step towards the disestablishment of the Romanian monarchy and the proclamation of a Communist regime

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Com ...

at the end of the following year. Breaking with the traditional universal male suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult male citizens within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification. It is sometimes summarized by the slo ...

confirmed by the 1923 Constitution, it was the first national election to feature women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to gran ...

, and the first to allow active public officials and army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

personnel the right to vote.Ștefan, p. 10; Țiu The BPD, representing the incumbent leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soc ...

government formed around Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Petru Groza

Petru Groza (7 December 1884 – 7 January 1958) was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian politician, best known as the first Prime Minister of the Communist Party-dominated government under Soviet occupation during the early stages of the Commu ...

, was an electoral alliance

An electoral alliance (also known as a bipartisan electoral agreement, electoral pact, electoral agreement, electoral coalition or electoral bloc) is an association of political parties or individuals that exists solely to stand in elections.

E ...

comprising the PCR, the Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Fo ...

(PSD), the Ploughmen's Front

The Ploughmen's Front ( ro, Frontul Plugarilor) was a Romanian left-wing agrarian-inspired political organisation of ploughmen, founded at Deva in 1933 and led by Petru Groza. At its peak in 1946, the Front had over 1 million members.

Hist ...

, the National Liberal Party–Tătărescu

The National Liberal Party–Tătărescu ( ro, Partidul Național Liberal-Tătărescu, PNL-Tătărescu) was a liberal and social liberal political party in the Kingdom of Romania and then in the Socialist Republic of Romania. It was established a ...

(PNL–Tătărescu), the National Peasants' Party–Alexandrescu (PNȚ–Alexandrescu) and the National Popular Party.

According to official results, the BPD won 69.8% of the vote, enough for an overwhelming majority of 347 seats in the 414-seat unicameral

Unicameralism (from ''uni''- "one" + Latin ''camera'' "chamber") is a type of legislature, which consists of one house or assembly, that legislates and votes as one.

Unicameral legislatures exist when there is no widely perceived need for multi ...

Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. ...

. Between them, the BPD and its allies won 379 seats, controlling over 91 percent of the chamber. The National Peasants' Party

The National Peasants' Party (also known as the National Peasant Party or National Farmers' Party; ro, Partidul Național Țărănesc, or ''Partidul Național-Țărănist'', PNȚ) was an agrarian political party in the Kingdom of Romania. It w ...

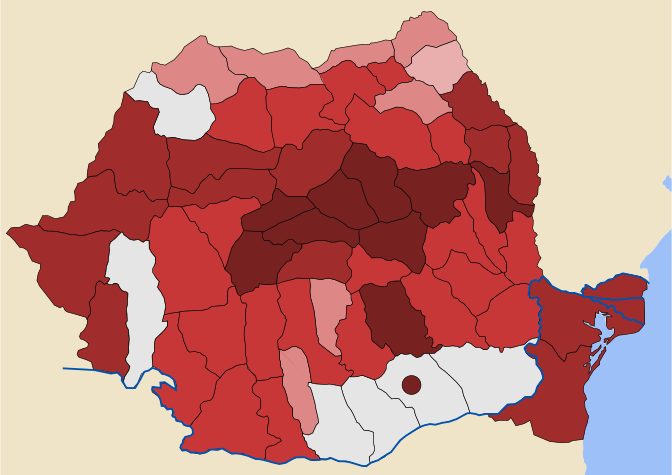

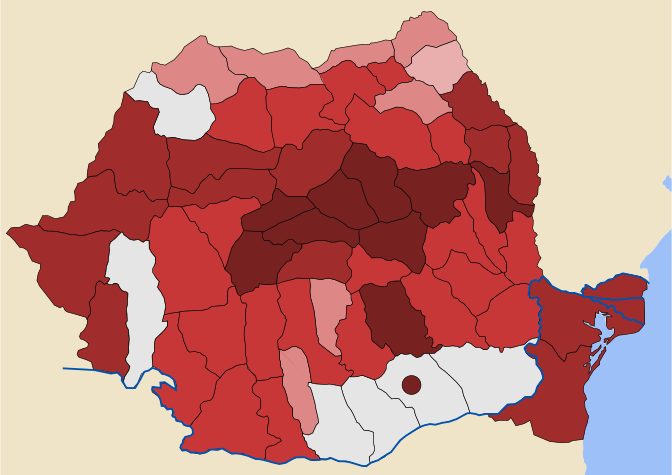

– Maniu (PNȚ–Maniu) won 32 seats and the National Liberal Party (PNL–Brătianu) only three.Ștefan, p. 9 In general, commentators agree that the BPD carried the vote through widespread intimidation tactics and electoral fraud, to the detriment of both the PNȚ–Maniu and the PNL–Brătianu. While there is disagreement over the exact results, it is contended that the BPD and its allies actually won no more than 48 percent of the total, with several authors assuming PNȚ–Maniu to be the overall winner. Journalist claims that the actual votes for the PNȚ–Maniu could have allowed it to form a government, either in its own right or as senior partner in a non-BPD coalition. Historian Marin Pop considers that this was the most fraudulent election in the history of Romanian politics. Various authors note however that the fraud has been mythologised by the opposition, including in its post-1990 installments. The 1946 elections were in many ways similar to the ones won by PNL–Brătianu or PNȚ before World War II: the governing party always used state resources in its campaign, ensuring for itself a comfortable majority, against clamorous accusations of fraud and violence coming from the opposition parties.

Carried out upon the close of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, under Romania's occupation by Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

troops, the elections have drawn comparisons to the similarly flawed elections held at the time in most of the emerging Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

(in Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Mac ...

, Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

), being considered, in respect to its formal system of voting, among the most permissive of the latter.Țârău, pp. 33–34

Background

Following its exit from theAxis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

in the wake of the coup d'état of 23 August 1944, Romania became subject to Allied supervision (''see Romania during World War II

Following the outbreak of World War II on 1 September 1939, the Kingdom of Romania under King Carol II officially adopted a position of neutrality. However, the rapidly changing situation in Europe during 1940, as well as domestic political uph ...

, Allied Commission

Following the termination of hostilities in World War II, the Allies were in control of the defeated Axis countries. Anticipating the defeat of Germany and Japan, they had already set up the European Advisory Commission and a proposed Far Easte ...

''). After the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

in February 1945, Soviet authorities had increased their presence in Romania, as Western Allied governments resorted to expressing largely inconsequential criticism of new procedures in place.Tismăneanu, p. 113 After the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

, the latter group initially refused to recognize Groza's administration, which had been imposed after Soviet pressure.

Consequently, King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the ...

Michael I Michael I may refer to:

* Pope Michael I of Alexandria, Coptic Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of the See of St. Mark in 743–767

* Michael I Rhangabes, Byzantine Emperor (died in 844)

* Michael I Cerularius, Patriarch Michael I of Constantin ...

refused to sign legislation advanced by the cabinet (this was the so-called ''Greva regală'', "Royal strike"). On 8 November 1945, authorities repressed a gathering of Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north ...

ers organized by the two main opposition parties in front of the Royal Palace

This is a list of royal palaces, sorted by continent.

Africa

* Abdin Palace, Cairo

* Al-Gawhara Palace, Cairo

* Koubbeh Palace, Cairo

* Tahra Palace, Cairo

* Menelik Palace

* Jubilee Palace

* Guenete Leul Palace

* Imperial Palace- Mass ...

.Cioroianu, ''Pe umerii...'', p. 62 Demonstrators, many of them young students, flocked to the plaza in front of the palace to express their solidarity with the monarch (on the Orthodox liturgics Saint Michael's Day); however, armed groups attacked the Ministries of Interior and Propaganda, as well as the headquarters of pro-government organisations, including the General Confederation of Labour and the Patriotic Defense."750.000 de cetățeni ai Capitalei au participat la manifestația de doliu național", pp. 1-4 in '' Scânteia'' (378). 13 November 1945 Following clashes with government supporters and troops, some 10 or 11 people were left dead and many injured. The government declared a national day of mourning

A national day of mourning is a day or days marked by mourning and memorial activities observed among the majority of a country's populace. They are designated by the national government. Such days include those marking the death or funeral of ...

, and state funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of Etiquette, protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive ...

s were held on 12 November for seven of the victims, hailed as fighters for democracy and independence, "assassinated by bands of fascist killers". Nevertheless, claims that, depicting the event as a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, ...

attempt, authorities had fired on the crowd. In January 1946, the "Royal strike" itself ended following the Moscow Conference, which made US and British recognition of the government dependent on the inclusion of two politicians from the main opposition parties. Consequently, the National Liberal and the National Peasants' Emil Hațieganu joined the cabinet as Minister without Portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet ...

.

In mid-December 1945, the representatives of the three major Allied Powers—Andrey Vyshinsky

Andrey Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (russian: Андре́й Януа́рьевич Выши́нский; pl, Andrzej Wyszyński) ( – 22 November 1954) was a Soviet politician, jurist and diplomat.

He is known as a state prosecutor of Josep ...

from the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, W. Averell Harriman from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

, and Archibald Clerk-Kerr from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

—visited the capital Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north ...

and agreed for elections to be convened in May 1946, on the basis of the Yalta Agreements. Nevertheless, the pro-Soviet Groza cabinet took the liberty to prolong the term, passing the required new electoral procedure on June 15.

On the same day, a royal decree was published abolishing the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

, turning the Parliament into a unicameral legislature

Unicameralism (from ''uni''- "one" + Latin ''camera'' "chamber") is a type of legislature, which consists of one house or assembly, that legislates and votes as one.

Unicameral legislatures exist when there is no widely perceived need for multi ...

, the ''Assembly of Deputies'' (''Adunarea Deputaților''). The new legislation, revising the 1923 Constitution, was made possible by the fact that Groza was governing without a parliament (the last legislature to have functioned, that of the National Renaissance Front

The National Renaissance Front ( ro, Frontul Renașterii Naționale, FRN; also translated as ''Front of National Regeneration'', ''Front of National Rebirth'', ''Front of National Resurrection'', or ''Front of National Renaissance'') was a Romani ...

, had been dissolved in 1941).Țiu The Senate was traditionally considered reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the '' status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abs ...

by the PCR, with historian Marian Ștefan arguing the measure was meant to facilitate control over the legislative processȘtefan, p. 10 The BPD government also removed the majority bonus

The majority bonus system (MBS) is a form of semi-proportional representation used in some European countries. Its feature is a majority bonus which gives extra seats or representation in an elected body to the party or to the joined parties with ...

, awarded since 1926 to the party that had obtained more than 40% of the total suffrage.

The election coincided with the deterioration of relations between the Soviet Union and the West at the start of the Cold War, notably marked by Winston Churchill's "Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its s ...

" speech at Westminster College on 5 March 1946,Macuc, p. 40 and the centering of Western Allied interest in turning the tide of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wit ...

. The intricate issues posed by the latter contributed to weakening ties between the Romanian opposition groups and their Western supporters.

The date of the election coincided with the fourth anniversary of Operation Uranus

Operation Uranus (russian: Опера́ция «Ура́н», Operatsiya "Uran") was the codename of the Soviet Red Army's 19–23 November 1942 strategic operation on the Eastern Front of World War II which led to the encirclement of Axi ...

, the moment when Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and Romania suffered a major defeat on the Eastern Front at the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later re ...

. According to his private notes, General Constantin Sănătescu, an adversary of the PCR and former Premier, presumed that this had been done on purpose ("in order to mock us").

BPD

Following Romania's exit from the war,left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in so ...

parties had increased their membership several times. The PCR, which held its first open and legal conference in October 1945, had begun a massive recruitment campaign. By 1947, it grew to 600,000-700,000 members from an initial 1,000 in 1944 (the constant growth in membership was by far the highest of all Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

countries).

Similarly, the Ploughmen's Front

The Ploughmen's Front ( ro, Frontul Plugarilor) was a Romanian left-wing agrarian-inspired political organisation of ploughmen, founded at Deva in 1933 and led by Petru Groza. At its peak in 1946, the Front had over 1 million members.

Hist ...

, which Groza presided, was estimated to have 1,000,000–1,500,000 members or just 800,000.PCR report, in Țurlea, p. 35 In early November 1946, Communist sources show that the BPD counted an important part of the gains in the rural areas to be obtained from the Front's electorate (the poor and middle peasant categories). By the time of the election, Groza's party had just been pressured into supporting Communist tenets, after it a brief conflict had erupted over the PCR's designs of collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

.

The Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Fo ...

(PSD), which had been drawn into close collaboration with the PCR as early as 1944 (as part of the United Workers' Front, ''Frontul Unic Muncitoresc''), had also seen a steady growth in numbers; the PSD was by then dominated by the pro-PCR wing of Ștefan Voitec and Lothar Rădăceanu, who purged the staunchly Reformist

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can ...

group of Constantin Titel Petrescu

Constantin Titel Petrescu (5 February 1888 – 2 September 1957) was a Romanian politician and lawyer. He was the leader of the Romanian Social Democratic Party.

He was born in Craiova, the son of an employee of the National Bank in Buchare ...

in March 1946 (leading the latter to establish his own independent group). The Communist Ana Pauker

Ana Pauker (born Hannah Rabinsohn; 13 February 1893 – 3 June 1960) was a Romanian communist leader and served as the country's foreign minister in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Ana Pauker became the world's first female foreign minister wh ...

noted with dissatisfaction that certain members of the PSD continued to remain hostile to her party (she cited the example of an unnamed intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator o ...

and low-ranking member of the PSD who, during a BPD meeting, shouted a slogan in support of the PNȚ's Iuliu Maniu

Iuliu Maniu (; 8 January 1873 – 5 February 1953) was an Austro-Hungarian-born lawyer and Romanian politician. He was a leader of the National Party of Transylvania and Banat before and after World War I, playing an important role in the U ...

).Pauker, quoted by Shutov, Document 234, 20 November 1946, in Pokivailova, p. 13

As a representative of the middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Co ...

, the National Liberal Party–Tătărescu

The National Liberal Party–Tătărescu ( ro, Partidul Național Liberal-Tătărescu, PNL-Tătărescu) was a liberal and social liberal political party in the Kingdom of Romania and then in the Socialist Republic of Romania. It was established a ...

itself had an uneasy relation with the PCR, having declared its support for capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

.

The Hungarian People's Union (UPM or MNSZ), which represented the Hungarian minority was instrumental in securing Transylvanian votes for the government coalition, as admitted by the PCR itself. Nevertheless, the pro-communist commander of the 4th Army Corps saw the overwhelming vote for the UPM among the soldiers and PCR members of Hungarian origin as an indication of "chauvinism

Chauvinism is the unreasonable belief in the superiority or dominance of one's own group or people, who are seen as strong and virtuous, while others are considered weak, unworthy, or inferior. It can be described as a form of extreme patriotism ...

".General Precup Victor, Nr.7 (23 November 1946), in Troncotă, p. 19 The BPD also won the endorsement of the Jewish Democratic Committee

The Jewish Democratic Committee or Democratic Jewish Committee ( ro, Comitetul Democrat Evreiesc, CDE, also ''Comitetul Democrat Evreesc'', ''Comitetul Democratic Evreiesc''; he, הוועד הדמוקרטי היהודי; hu, Demokrata Zsidó Komi ...

, which included members of Jewish-Romanian community favourable to the PCR.

With their organization banned in accordance with the 1944 armistice agreement, members of the fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

Iron Guard

The Iron Guard ( ro, Garda de Fier) was a Romanian militant revolutionary fascist movement and political party founded in 1927 by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu as the Legion of the Archangel Michael () or the Legionnaire Movement (). It was strong ...

adopted an entryist tactic, infiltrating all legally-existing parties. One of the most notable cases was that of underground leader Horaţiu Comaniciu, who urged former guardists to join the opposition National Peasants' Party

The National Peasants' Party (also known as the National Peasant Party or National Farmers' Party; ro, Partidul Național Țărănesc, or ''Partidul Național-Țărănist'', PNȚ) was an agrarian political party in the Kingdom of Romania. It w ...

. In a bid to escape punishment for their crimes some even joined the Communists. A report of November 1945 indicates that, of the 15,538 former Iron Guard members known to have joined political parties, 2,258 chose PCR, while 3,281 entered the PSD.

Historians suggest that, at the time, government-backed Communists had infiltrated the vast majority of the media and cultural institutions. On one occasion, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

general Ivan Susaykov warned Nicolae Carandino Nicolae Carandino (19 July 1905 – 16 February 1996) was a Romanian journalist, pamphleteer, translator, dramatist, and politician.

He was born in Brăila into a family of intellectuals, the son of a Romanian mother and Greek father. After com ...

, editor-in-chief of the PNȚ's ''Dreptatea

''Dreptatea'' was a Romanian newspaper that appeared between 17 October 1927 and 17 July 1947, as a newspaper of the National Peasants' Party. It was re-founded on February 5, 1990 as a publication of the Christian-Democratic National Peasants' ...

'', to tone down his criticism of the government, and reportedly argued that "the Groza government is Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

itself".

Electoral system

New legislation provided for the end ofuniversal male suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult male citizens within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification. It is sometimes summarized by the slo ...

, proclaiming the right to vote

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

for all citizens over the age of 21, while restricting it for all persons who had held important office during the wartime dictatorship of ''Conducător

''Conducător'' (, "Leader") was the title used officially by Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu during World War II, also occasionally used in official discourse to refer to Carol II and Nicolae Ceaușescu.

History

The word is derived from the Ro ...

'' Ion Antonescu

Ion Antonescu (; ; – 1 June 1946) was a Romanian military officer and marshal who presided over two successive wartime dictatorships as Prime Minister and '' Conducător'' during most of World War II.

A Romanian Army career officer who ma ...

. The latter requirement facilitated abuse, as power to decide over who had been supporting the regime fell to "purging commissions", all of them controlled by the PCR, and the Romanian People's Tribunals The two Romanian People's Tribunals ( ro, Tribunalele Poporului), the Bucharest People's Tribunal and the Northern Transylvania People's Tribunal (which sat in Cluj) were set up by the post-World War II government of Romania, overseen by the Allied ...

(investigating war crimes, and constantly supported by agitprop

Agitprop (; from rus, агитпроп, r=agitpróp, portmanteau of ''agitatsiya'', "agitation" and ''propaganda'', "propaganda") refers to an intentional, vigorous promulgation of ideas. The term originated in Soviet Russia where it referred ...

in the Communist press).

The decision to allow military men and public officials to vote was also intended to secure a grip on elections. At the time, Groza's cabinet exercised complete control over public administration at central and local levels, as well as the means of communication. Soviet sources cited PCR officials giving assurances that the respective categories were to provide as much as 1 million votes for the BPD.

A report of the Soviet Embassy in Bucharest, dated 15 August 1946, informed Andrey Vyshinsky

Andrey Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (russian: Андре́й Януа́рьевич Выши́нский; pl, Andrzej Wyszyński) ( – 22 November 1954) was a Soviet politician, jurist and diplomat.

He is known as a state prosecutor of Josep ...

of the legislative changes and made note of the fact that the two opposition leaders, Iuliu Maniu

Iuliu Maniu (; 8 January 1873 – 5 February 1953) was an Austro-Hungarian-born lawyer and Romanian politician. He was a leader of the National Party of Transylvania and Banat before and after World War I, playing an important role in the U ...

(leader of the PNȚ–Maniu) and Dinu Brătianu (leader of the PNL–Brătianu), had asked King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the ...

Michael I Michael I may refer to:

* Pope Michael I of Alexandria, Coptic Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of the See of St. Mark in 743–767

* Michael I Rhangabes, Byzantine Emperor (died in 844)

* Michael I Cerularius, Patriarch Michael I of Constantin ...

not to approve the new framework. The two parties had not been allowed to take any part in drafting the new legal framework.

Early estimates

Months before the election, Communist leaders expressed confidence in being able to carry the election by 70 or 80% (statement of theMinister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

Teohari Georgescu

Teohari Georgescu (January 31, 1908 – December 31, 1976) was a Romanian statesman and a high-ranking member of the Romanian Communist Party.

Early life

Born in Chitila, near Bucharest, he was the third of seven children of Constantin and An ...

during a party plenary, and Constantin Vișoianu's report about an alleged declaration of Minister of Justice Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu

Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu (; November 4, 1900 – April 17, 1954) was a Romanian communist politician and leading member of the Communist Party of Romania (PCR), also noted for his activities as a lawyer, sociologist and economist. For a while, he ...

), or even 90% ( Miron Constantinescu, head of the PCR's '' Scînteia'' newspaper).Giurescu, "Marea fraudă...", Part II As early as May, former Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between coun ...

Constantin Vișoianu complained to Adrian Holman

Sir Adrian Holman KBE CMG MC (22 December 1895 – 6 September 1974) was a British diplomat.

Early life

The son of Richard Haswell Holman, he was educated at Copthorne Preparatory School, Harrow School, and New College, Oxford.

Career

H ...

, the British Ambassador to Romania

The Ambassador of the United Kingdom to Romania is the United Kingdom's foremost diplomatic representative in Romania, and head of the UK's diplomatic mission in Romania. The official title is ''His Britannic Majesty's Ambassador to Romania''.

...

, that the BPD had ensured the means to win the elections through fraud. Writing in January, Archibald Clerk-Kerr assessed the results of his visit to Romania, arguing that no person he had met actually trusted that elections were going to be free; furthermore, in an interview published after Vyshinsky's death, former US ambassador W. Averell Harriman claimed the Soviet diplomat believed in January 1946 that, on its own, the PCR was not capable of gathering more than 10% of the vote.

According to the American diplomat Burton Y. Berry

Burton Yost Berry (August 31, 1901 – August 22, 1985) was an American diplomat and art collector.

Born in Fowler, Indiana, Berry studied at Indiana University. In 1928 he joined the United States Foreign Service. Berry served as Vice-Consul to ...

, Groza had admitted to this procedure during an alleged conversation with a third party, indicating that the fraudulent percentages were the goal of competition between two sides — him and the PCR's general secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derive ...

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (; 8 November 1901 – 19 March 1965) was a Romanian communist politician and electrician. He was the first Communist leader of Romania from 1947 to 1965, serving as first secretary of the Romanian Communist Party ...

formed one, while a "Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

ist section" around Emil Bodnăraș

Emil Bodnăraș (10 February 1904 – 24 January 1976) was a Romanian communist politician, an army officer, and a Soviet agent, who had considerable influence in the Romanian People's Republic.''Final Report'', p. 646

Early life

Bodnăraș was ...

represented the other; according to Berry, Groza and Gheorghiu-Dej were satisfied with a less intrusive fraud and, thus, a more realistic result (60%), while Bodnăraș aimed for 90%. W. Averell Harriman, recording his conversation with Vyshinsky, alleged that the latter backed the 70% estimate. Nevertheless, the Soviet Ambassador Sergey Kavtaradze

Sergey or Sergo Kavtaradze ( Georgian: სერგო ქავთარაძე, ''Sergo Kavtaradze''; Russian: Сергей Иванович Кавтарадзе, ''Sergey Ivanovich Kavtaradze''; 15 August 1885 – 17 October 1971) was a Sovi ...

stated that, while the party leadership estimated winning 60-70%, "through certain 'techniques'", the BPD could win up to 90%. A reference to "techniques" was also made by Ana Pauker

Ana Pauker (born Hannah Rabinsohn; 13 February 1893 – 3 June 1960) was a Romanian communist leader and served as the country's foreign minister in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Ana Pauker became the world's first female foreign minister wh ...

in conversation with Soviet officials; she nevertheless expressed her belief that, without such techniques, the overall result was not going to be upwards of 60% (Pauker also voiced concern that such a figure, while a victory for the BPD coalition, would result in a minority for the PCR itself).Pauker, quoted by Shutov, Document 234, 20 November 1946, in Pokivailova, p. 14

Historian Adrian Cioroianu assessed that the dissemination of optimistic rumors contributed to accustoming the public to the idea that the government could obtain the majority of the votes, and made the ultimate result less questionable in the eyes of observers.Cioroianu, p. 65

Other Soviet documents, dated November 6 and 12, summarize a conversation with Bodnăraș, who went on record indicating that fraud was being prepared to raise the percentage from 55-65% to 90%; compared to the mandates awarded to the BPD according to the official results, his estimation came within 1%, though this was not the case for the mandates obtained by other competitors. Kavtaradze expressed concern that information on this topic had leaked out to opposition parties in various locations, and that the PCR had thus failed to fully respect the "conspiratorial

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

character" it had decided to use.

Economic and social issues

An expectation shared by Groza and the PCR in postponing the elections was that the outcome of harvests was to ensure the most favorable attitude from peasant voters (" rozahas declared that the government will only organize elections «when the barns are filled with wheat»"). This tactic was consistently applied by parties in government during the interwar period. Conversely, the opposition wanted to postpone the elections until after the Peace Treaty with the Allies had been signed, hoping that the withdrawal of Soviet troops would allow greater intervention of the Western Allies in Romanian internal matters. The summer of 1946 brought an exceptionally severedrought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

, which led to famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accom ...

in some areas. In a discussion with Soviet embassy staff, PCR leader Ana Pauker

Ana Pauker (born Hannah Rabinsohn; 13 February 1893 – 3 June 1960) was a Romanian communist leader and served as the country's foreign minister in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Ana Pauker became the world's first female foreign minister wh ...

claimed that this had been worsened by administrative incompetence, which had led to insufficient supplies of wheat and bread at the central level, and to various irregularities in transport over the national railway system which she attributed to sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identiti ...

. Kavtaradze blamed the government itself for failing to prepare the economy for the elections. Pauker further mentioned that Communists were especially concerned about events related to the petroleum industry

The petroleum industry, also known as the oil industry or the oil patch, includes the global processes of hydrocarbon exploration, exploration, extraction of petroleum, extraction, oil refinery, refining, Petroleum transport, transportation (of ...

in Romania (centered on Prahova County

Prahova County () is a county (județ) of Romania, in the historical region Muntenia, with the capital city at Ploiești.

Demographics

In 2011, it had a population of 762,886 and the population density was 161/km². It is Romania's third most ...

), which was by then becoming much less lucrative. Tudor Ionescu

Tudor most commonly refers to:

* House of Tudor, English royal house of Welsh origins

** Tudor period, a historical era in England coinciding with the rule of the Tudor dynasty

Tudor may also refer to:

Architecture

* Tudor architecture, the fin ...

, the PSD's Minister of Mines and Petroleum, supported the initiative of American and British businessmen to withdraw their investments, but was opposed by the PCR, who argued that this was a move to undermine support for the government, by leaving thousands of people unemployed. Pauker also declared that a similar move was to be carried out by Ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

's Bucharest branch. Kavtaradze noted dissatisfaction among workers, civil servants, and Romanian Army

The Romanian Land Forces ( ro, Forțele Terestre Române) is the army of Romania, and the main component of the Romanian Armed Forces. In recent years, full professionalisation and a major equipment overhaul have transformed the nature of the La ...

personnel over their low incomes.Kavtaradze, Document 234, 20 November 1946, in Pokivailova, p. 14

In this context, the government began handing out food supplies. Pauker attested that, in several places, the state was frustrated in its attempt to purchase grain from peasants, who argued that the price was too low, and that this led to the supplies being insufficient. The government eventually took the decision to import grain (and especially maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn ( North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. ...

) in large quantities, an action overseen by Gheorghiu-Dej. According to Kavtardze, such measures were partly ineffective.

Pauker's testimony stressed that, while problems in applying the land reform damaged the BPD's image in some counties in rural regions, its main support came from the formerly landless peasantry. She also attested that, in several counties

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposes Chambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

in Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centra ...

, the absentee ballot

An absentee ballot is a vote cast by someone who is unable or unwilling to attend the official polling station to which the voter is normally allocated. Methods include voting at a different location, postal voting, proxy voting and online vot ...

was becoming an option among members of the latter social category ("Asked whom they would vote for, peasants answer: «We'll think about it some more» or «We shall not be voting»"). While disheartened by the government's apparent failure to provide help, the peasants also distrusted the opposition's PNȚ–Maniu, whom they saw as representative of the landlords and opposed to the land reform. According to Pauker, they were falling for PNȚ–Maniu's propaganda, which claimed the Groza cabinet had carried out the land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultur ...

only as a preliminary step to collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

("Peasants answer that in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

as well, in the beginning the land was divided, then taken away and ''kolkhoz

A kolkhoz ( rus, колхо́з, a=ru-kolkhoz.ogg, p=kɐlˈxos) was a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union. Kolkhozes existed along with state farms or sovkhoz., a contraction of советское хозяйство, soviet ownership o ...

y'' were set up. We have no convincing arguments against such objections from the peasants").Pauker, quoted by Shutov, Document 234, 20 November 1946, in Pokivailova, p. 14

The BPD took additional measures in regard to women voters in villages, most of them illiterate

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, hum ...

. According to Pauker, several agitprop

Agitprop (; from rus, агитпроп, r=agitpróp, portmanteau of ''agitatsiya'', "agitation" and ''propaganda'', "propaganda") refers to an intentional, vigorous promulgation of ideas. The term originated in Soviet Russia where it referred ...

campaigns were aimed at them, during which Communist activists stressed the positive aspects of the Groza government. Pauker stated: "a lot of things will depend on how the presidents of election bureaus treat women voters, since women have never voted, have never seen electoral laws and are not aware of voting procedures". The UPM also actively campaigned among women, with its propaganda considered to be better than PCR's even by government agents. In one incident, witnessed during the elections and occurring in Cluj

; hu, kincses város)

, official_name=Cluj-Napoca

, native_name=

, image_skyline=

, subdivision_type1 = County

, subdivision_name1 = Cluj County

, subdivision_type2 = Status

, subdivision_name2 = County seat

, settlement_type = City

, le ...

, "there was an unexpected turnout of Magyar women. Old women aged 70–80, carrying chairs, had queued, in rainy weather, awaiting their turn to vote. The slogan was: if one does not vote with the UPM, one does not receive sugar".

The women's suffrage was regarded with a level of hostility by the PNŢ–Maniu, and ''Dreptatea

''Dreptatea'' was a Romanian newspaper that appeared between 17 October 1927 and 17 July 1947, as a newspaper of the National Peasants' Party. It was re-founded on February 5, 1990 as a publication of the Christian-Democratic National Peasants' ...

'' frequently ridiculed Pauker's visits to women in various villages.

Conduct

General irregularities

The period of campaigning and the election itself were witness to widespread irregularities, with historian and politician Dinu C. Giurescu claiming violence and intimidation were carried out both by squads of the BPD and by those of the opposition. In one instance, in Piteşti, a local leader of the PNȚ was killed in the headquarters of the local prosecutor.Giurescu, "«Alegeri» după model sovietic", p. 18 Prior to the election,freedom of association

Freedom of association encompasses both an individual's right to join or leave groups voluntarily, the right of the group to take collective action to pursue the interests of its members, and the right of an association to accept or decline mem ...

had been severely curtailed through various laws; according to Burton Y. Berry

Burton Yost Berry (August 31, 1901 – August 22, 1985) was an American diplomat and art collector.

Born in Fowler, Indiana, Berry studied at Indiana University. In 1928 he joined the United States Foreign Service. Berry served as Vice-Consul to ...

, Groza had admitted to this, and had indicated that it was in answer to the need for order in the country. Expanding on this, he stated that the cabinet was attempting to prevent "provocations" from both the far right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

and far left, and that chaos during the elections would have resulted in his own sidelining and a dictatorship of the far left.Groza, quoted by Berry, in Giurescu, "«Alegeri» după model sovietic", p. 18 In regard to the arrest of several Romanian employees of the American Embassy in Bucharest, Groza reportedly claimed that he had tried to set them free, but the "extremists in the government" had opposed this move. According to the opposition PNȚ's newspaper, he had reportedly stated in a February 1946 meeting with workers: "If the reaction

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure:

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

*Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

* Chain reaction (disambiguation).

Biology and me ...

wins, do you think we'll let it live for nother

Amalie Emmy NoetherEmmy is the ''Rufname'', the second of two official given names, intended for daily use. Cf. for example the résumé submitted by Noether to Erlangen University in 1907 (Erlangen University archive, ''Promotionsakt Emmy Noethe ...

24 hours? We'll be getting our payback immediately. We'll get our hands on whatever we can and we'll strike".

According to Berry, the Premier had stated that he assessed Romania's commitment to freedom of election in opposition to the Western Allied requirements, and based on "the Russian interpretation of «free and unfettered»".

One effect of new legislative measures was that the intervention of judicial authorities as observers was much reduced; the task fell instead on local authorities, which Communist supporters had infiltrated in the previous two years.

From the start, state resources were employed in campaigning for the BPD. The numbers cited by Victor Frunză include, among other investments, over 4 million propaganda booklets, 28 million leaflets, 8.6 million printed caricatures, 2.7 million signs, and over 6.6 million posters.Frunză, p. 290

Army

There is evidence that the Army was a main agent of both political campaigning and the eventual fraud. In order to counteract malcontent in military ranks caused by serious housing and supply issues, as well as the high level of inflation, the Groza cabinet increased their revenues and supplies preferentially. In January, Armyagitprop

Agitprop (; from rus, агитпроп, r=agitpróp, portmanteau of ''agitatsiya'', "agitation" and ''propaganda'', "propaganda") refers to an intentional, vigorous promulgation of ideas. The term originated in Soviet Russia where it referred ...

sections of the "Education, Culture and Propaganda" Directorate (''Direcția Superioară pentru Educație, Cultură și Propagandă a Armatei'', or ECP), already employed in channeling political messages inside military ranks, were authorized to carry out "educational activities" outside of the facilities and in rural areas. PNȚ and PNL activists were barred entry to Army bases, while the ECP closely supervised soldiers who supported the opposition, and repeatedly complained about the "political backwardness" and "liberties in voting" of various Army institutions. While several Army officials guaranteed that their subordinates would vote for the BPD unanimously,Duțu, p. 38 low-ranking members occasionally expressed criticism over the violent quelling of PNȚ and PNL–Brătianu activities inside Army units.

Eventually, as the institution made use of its venues to campaign for the BPD,Macuc, p. 41 it encountered hostility. At a time when the airplanes of the Romanian Air Force

The Romanian Air Force (RoAF) ( ro, Forțele Aeriene Române) is the air force branch of the Romanian Armed Forces. It has an air force headquarters, an operational command, five airbases and an air defense brigade. Reserve forces include one ai ...

were used to drop pro-Groza leaflets over the city of Brașov

Brașov (, , ; german: Kronstadt; hu, Brassó; la, Corona; Transylvanian Saxon: ''Kruhnen'') is a city in Transylvania, Romania and the administrative centre of Brașov County.

According to the latest Romanian census ( 2011), Brașov has a po ...

, EPC activists were alarmed to find out that the manifestos had been secretly replaced with PNȚ–Maniu propaganda.

The Army was assigned its own Electoral Commission, placed under the leadership of two notoriously pro-Soviet generals, Nicolae Cambrea and Mihail Lascăr

Mihail Lascăr (; November 8, 1889 – July 24, 1959) was a Romanian general during World War II and Romania's Minister of Defense from 1946 to 1947.

He was born in Târgu Jiu, Gorj County, Kingdom of Romania, and

graduated from the Infantry ...

, both of whom had formerly served in Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

units of Romanian volunteers. This drew unanswered protests from the opposition, who called for another Commission to be appointed. By the time of the election, the Groza cabinet decided not to allow reserve and recently discharged soldiers to vote at special Army stations, in order to prevent "tainting" the "real results". In one report from Cluj County

Cluj County (; german: Kreis Klausenburg, hu, Kolozs megye) is a county (județ) of Romania, in Transylvania. Its seat ( ro, Oraș reședință de județ) is Cluj-Napoca (german: Klausenburg).

Name

In Hungarian, it is known as ''Kolozs megye' ...

, General Precup Victor stated that:

An electoral section for the military inCluj ; hu, kincses város) , official_name=Cluj-Napoca , native_name= , image_skyline= , subdivision_type1 = County , subdivision_name1 = Cluj County , subdivision_type2 = Status , subdivision_name2 = County seat , settlement_type = City , le ...��almost declared the voting invalid, citing for reason that the election was declared over between 6 and 7 o'clock, instead of 8 o'clock, as was required by law. ��It is only due to the immediate and energetic intervention of the prefect, ithMajor Nicolae Haralambie, and yours truly that the situation was saved.

In this section, where we believed we had the best comrade president, and thus expected the best result, we received the worst result of all voting stations for the military. ��/blockquote>All of this because of the attitude of Comrade Petrovici he section president If this section had not existed or if Comrade Petrovici, as its president, had listened to us, the army would have yielded a 99% result and not 92.06, as it came to be in Cluj."Immediately after the elections, pro-Communist General , commander of the Fourth Army Corps, ordered the arrest of General Drăgănescu of the Second Division of ''Vânători de munte Vânători may refer to several places: Romania * Vânători, Galați, a commune in Galați County * Vânători, Iași, a commune in Iaşi County * Vânători, Mehedinți, a commune in Mehedinţi County * Vânători, Mureș, a commune in Mureș ...'' in Dej, alleging that, during the voting, he exaggerated the extent of unrest among local peasant population in Dej, which was engaged inAntisemitic Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism. Ant ...and Anti-Hungarian violence, as a means to draw the interest of central authorities and Western Allied supervisors. In a secret note released at the same time, General Precup admitted that violent incidents against the government and its supporters had been occurring, and that the Army had been sent in to intervene. He also admitted that local supporters of the PNȚ–Maniu were upset with the official results.

Other testimonies

Writing at the time, the academicConstantin Rădulescu-Motru Constantin Rădulescu-Motru (; born Constantin Rădulescu, he added the surname ''Motru'' in 1892; February 15, 1868 – March 6, 1957) was a Romanian philosopher, psychologist, sociologist, logician, academic, dramatist, as well as left-nati ..., who had his electoral rights suspended due to wartime membership of the Romanian-German Association, reported rumours that authorities had been arbitrarily preventing people from voting, that many voters were not asked for their documents, and that electoral lists marked with the Sun symbol of the BPD had been shoved into urns before voting began. Such a rumour was that:Trucks filled with voters f the BPDtraveled from one section to the other and voted in all sections, that is to say several times. After voting, blank forms of official reports y observerswere sent to the central commission, and they were filled in by adding the number of votes desired by the government".According to Anton Rațiu and Nicolae Betea, two collaborators ofLucrețiu Pătrășcanu Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu (; November 4, 1900 – April 17, 1954) was a Romanian communist politician and leading member of the Communist Party of Romania (PCR), also noted for his activities as a lawyer, sociologist and economist. For a while, he ..., the elections inArad County Arad County () is an administrative division ( judeţ) of Romania roughly translated into county in the western part of the country on the border with Hungary, mostly in the region of Crișana and few villages in Banat. The administrative cente ...were organized by a group of 40 people (including Belu Zilber and Anton Golopenția); the president of the county electoral commission collected the votes from local stations and was required to read them aloud—irrespective of the option expressed, he called out the names of BPD candidates (Pătrășcanu andIon Vincze Ion Vincze (born Vincze János and also called Ion or Ioan Vințe; September 1, 1910 – 1996) was a Romanian communist politician and diplomat. An activist of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR), he was married to Constanța Crăciun, herself a ..., together with others). Nicolae Betea stated that the overall results for the BPD in Arad County, officially recorded at 58%, were closer to 20%. Throughout the country, voting bulletins were set fire to immediately after the official counting was completed, an action which prevented all alternative investigation.

Official results

Alternative results

Sometime after the elections, the PCR issued a confidential report called "Lessons from the Elections and the C mmunistP rtys Tasks after the Victory of 19 November 1946" (, Arhiva MApN, fond Materiale documentare diverse, dosar 1.742, f.12–13). It was compared by historian Petre Țurlea with the official version, and provides essentially different data on the results. Analyzing the report, Țurlea contended that, overall, the BPD actually won between 44.98% and 47% of the vote. This not only contradicted the official results, but also opposition claims that they actually won as much as 80% of the vote.Țurlea, p. 35 In Țurlea's interpretation, the result, although coming at the end of fraudulent elections, could be counted as a victory of the opposition. The report also confirms that the BPD's popularity had been much higher in the urban areas than with the peasantry, while, despite expectations, women in the villages, under the influence of the priests, preferred voting for the PNȚ. While securing the votes of the state apparatus and theJewish Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...''petite bourgeoisie ''Petite bourgeoisie'' (, literally 'small bourgeoisie'; also anglicised as petty bourgeoisie) is a French term that refers to a social class composed of semi-autonomous peasants and small-scale merchants whose politico-economic ideologica ...'', the BPD was not able to make notable gains inside the categories of traditional PNȚ supporters.

Reactions

Later the same month, the British government ofClement Attlee Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Min ..., represented byAdrian Holman Sir Adrian Holman KBE CMG MC (22 December 1895 – 6 September 1974) was a British diplomat. Early life The son of Richard Haswell Holman, he was educated at Copthorne Preparatory School, Harrow School, and New College, Oxford. Career H ..., issued a note informing Foreign MinisterGheorghe Tătărescu : ''For the artist, see Gheorghe Tattarescu.'' Gheorghe I. Tătărescu (also known as ''Guță Tătărescu'', with a slightly antiquated pet form of his given name; 2 November 1886 – 28 March 1957) was a Romanian politician who served twice as P ...that, due to the numerous infringements, it did not recognize the result of elections in Romania. In his 4 January 1947 conversation with theUnited States The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...Secretary of StateGeorge Marshall George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ..., Romania's Ambassador Mihai Ralea received an official American reproach for having "broken the spirit and letter" of the Moscow Conference and theYalta Agreement The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post .... Although Ralea, a Ploughmen's Front member and possibly an ally of the Communists, expressed concern over the fact that the United States were reproving Romania, he also appealed to the United States not to allow the country to be left behind theIron Curtain The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its s .... In August 1946, Berry attested that Groza intended to tighten connections with the other countries in theBalkans The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...andEastern Europe Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, wh ..., as the basis for acustoms union A customs union is generally defined as a type of trade bloc which is composed of a free trade area with a common external tariff.GATTArticle 24 s. 8 (a) Customs unions are established through trade pacts where the participant countries set up .... Giurescu compares this with the plan of a federation betweenBulgaria Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Mac ...andYugoslavia Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ..., advocated byGeorgi Dimitrov Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov (; bg, Гео̀рги Димитро̀в Миха̀йлов), also known as Georgiy Mihaylovich Dimitrov (russian: Гео́ргий Миха́йлович Дими́тров; 18 June 1882 – 2 July 1949), was a Bulgarian ...andJosip Broz Tito Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ..., which was frustrated by the opposition ofJoseph Stalin Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ..., and discarded altogether following the Tito-Stalin Split.

Aftermath

The election results effectively confirmed Romania's adherence to theEastern Bloc The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...and Soviet camp in the erupting Cold War. On 19 November the three opposition parties (theNational Peasants' Party The National Peasants' Party (also known as the National Peasant Party or National Farmers' Party; ro, Partidul Național Țărănesc, or ''Partidul Național-Țărănist'', PNȚ) was an agrarian political party in the Kingdom of Romania. It w ...–Maniu, the National Liberal Party–Brătianu andConstantin Titel Petrescu Constantin Titel Petrescu (5 February 1888 – 2 September 1957) was a Romanian politician and lawyer. He was the leader of the Romanian Social Democratic Party. He was born in Craiova, the son of an employee of the National Bank in Buchare ...'s splinter group from theSocial Democrats Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...) issued a formal protest, accusing the Groza government of having falsified the vote. Cabinet representatives of the two contender parties, the PNL–Brătianu's and the PNŢ–Maniu's Emil Hațieganu withdrew in protest soon after results were announced. Petre Ţurlea contends that the document was largely inconsequential due to theinterwar In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relativel ...tradition of similar protests for less problematic votes. On 1 December 1946, Premier Groza inaugurated the new unicameralParliament In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. .... In his speech on the occasion, while expressing a hope that elections had voted in a new type of legislative, he stressed that it was importantto eliminate the spectacle of useless blabber and personal issues from this Assembly and for these deputies to dedicate themselves, during the rather expensive session ��to an intensive activity.Groza, in Ioan, p. 16According to Groza:it is not the Parliament of old politicians, it is not a luxurious habit, an entertainment, an exercise of political gymnastics or an excuse for quarreling with others.In following months, Communists concentrated on silencing opposition and ensuring a monopoly on power. In summer 1947, the Tămădău Affair saw the end of the PNŢ–Maniu, banned afterIuliu Maniu Iuliu Maniu (; 8 January 1873 – 5 February 1953) was an Austro-Hungarian-born lawyer and Romanian politician. He was a leader of the National Party of Transylvania and Banat before and after World War I, playing an important role in the U ...and others were prosecuted during a show trial. The National Liberal Party-Tătărescu, which issued a critique of the Groza administration at around the same time, was forced out of the government and from the BPD, only to be implicated in the Tămădău scandal and have its leadership replaced with one more loyal to the PCR. The PCR ultimately merged with the PSD in late 1947 to form the Romanian Workers' Party (PMR), with the first dominating the leadership of the united party. According to journalist Victor Frunză, for all intents and purposes, however, the PMR was the PCR under a new name. In the last days of December 1947,King King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king. *In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the ...Michael I Michael I may refer to: * Pope Michael I of Alexandria, Coptic Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of the See of St. Mark in 743–767 * Michael I Rhangabes, Byzantine Emperor (died in 844) * Michael I Cerularius, Patriarch Michael I of Constantin ...was pressured intoabdication Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ .... The Communist-dominated legislature then abolished the monarchy and proclaimed Romania a "people's republic People's republic is an official title, usually used by some currently or formerly communist or left-wing states. It is mainly associated with soviet republics, socialist states following people's democracy, sovereign states with a democratic- r ...," marking the first stage of undisguised Communist rule in Romania.Cioroianu, pp. 97–101; Frunză, pp. 319–326

Notes

References

*Daniel Barbu, "Destinul colectiv, servitutea involuntară, nefericirea totalitară: trei mituri ale comunismului românesc" interbelică la communism" ("Collective Destiny, Involuntary Servitude, Totalitarian Misery: Three Myths of Romanian Communism"), pp. 175–197, inLucian Boia Lucian Boia (born 1 February 1944 in Bucharest Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the ..., ed., ''Miturile comunismului românesc'' ("The Myths of Romanian Communism"), Editura Nemira, Bucharest, 1998 *Lavinia Betea, "Portret în gri. Pătrășcanu – deputat de Arad" ("Portrait in Grey. Pătrășcanu – a Deputy for Arad"), in ''Magazin Istoric'', June 1998 * Adrian Cioroianu, ''Pe umerii lui Marx. O introducere în istoria comunismului românesc'' ("On the Shoulders of Marx. An Incursion into the History of Romanian Communism"), Editura Curtea Veche, Bucharest, 2005 * Dinu C. Giurescu, "Marea fraudă electorală din 1946" ("The Large-Scale Electoral Fraud of 1946")

Part II

an

Part VI