18th Century London on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 18th century was a period of rapid growth for London, reflecting an increasing national population, the early stirrings of the

New mansions built in this period include

New mansions built in this period include

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, and London's role at the centre of the evolving British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. It saw immigrants and visitors from all over the world, particularly Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

migrants from France. The built-up area of London increased dramatically in this period, particularly westward as areas such as Mayfair

Mayfair is an area of Westminster, London, England, in the City of Westminster. It is in Central London and part of the West End. It is between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane and one of the most expensive districts ...

and Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also ) is an area in London, England, and is located in the City of Westminster. It is in Central London and part of the West End. Oxford Street forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropo ...

were constructed. Grand aristocratic mansions such as Spencer House Spencer House may refer to:

* Spencer House, Westminster, Greater London, England

United States

* Spencer House (Hartford, Connecticut), listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in Hartford County

* Spencer House in Columbus, ...

were built, as well as churches such as St. Martin-in-the-Fields and Christ Church Spitalfields

Christ Church Spitalfields is an Anglican church built between 1714 and 1729 to a design by Nicholas Hawksmoor. On Commercial Street in the East End and in today's Central London it is in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, on its western bor ...

.

Crime such as armed robbery and sex work were particularly prevalent, leading to the development of early police forces such as the Bow Street Runners

The Bow Street Runners were the law enforcement officers of the Bow Street Magistrates' Court in the City of Westminster. They have been called London's first professional police force. The force originally numbered six men and was founded in 1 ...

and the Thames River Police

The Thames River Police was formed in 1800 to tackle theft and looting from ships anchored in the Pool of London and in the lower reaches and docks of the Thames. It replaced the Marine Police, a police force established in 1798 by magistrate ...

. Capital and corporal punishment such as hanging, penal transportation

Penal transportation (or simply transportation) was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies bec ...

and the pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, used during the medieval and renaissance periods for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. ...

were used, but the period also saw the development of penitentiary prisons such as that at Coldbath Fields. Londoners saw widespread violence during upheavals such as the Gordon Riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were several days' rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. They began with a large and orderly protest against the Papists Act 1778, which was intended to reduce official discrimination against British ...

.

Many modern-day cultural institutions come from 18th century London, such as the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, commonly known as the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), is a learned society that champions innovation and progress across a multitude of sectors by fostering creativity, s ...

, the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House in Piccadilly London, England. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its ...

, the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

, the Royal Thames Yacht Club

The Royal Thames Yacht Club (RTYC) is the oldest continuously operating yacht club in the world, and the oldest yacht club in the United Kingdom. Its headquarters are located at 60 Knightsbridge, London, England, overlooking Hyde Park. The clu ...

, Lord's Cricket Ground

Lord's Cricket Ground, commonly known as Lord's, is a cricket List of Test cricket grounds, venue in St John's Wood, Westminster. Named after its founder, Thomas Lord, it is owned by Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) and is the home of Middlesex C ...

, ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'', ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. First published in 1791, it is the world's oldest Sunday newspaper.

In 1993 it was acquired by Guardian Media Group Limited, and operated as a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' ...

,'' Theatre Royal Haymarket

The Theatre Royal Haymarket (also known as Haymarket Theatre or the Little Theatre) is a West End theatre in Haymarket in the City of Westminster which dates back to 1720, making it the third-oldest London playhouse still in use. Samuel Foote ...

, and the Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is a theatre in Covent Garden, central London. The building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. The ROH is the main home of The Royal Opera, The Royal Ballet, and the Orch ...

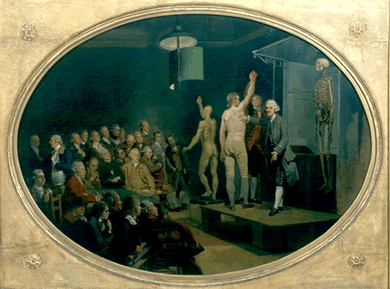

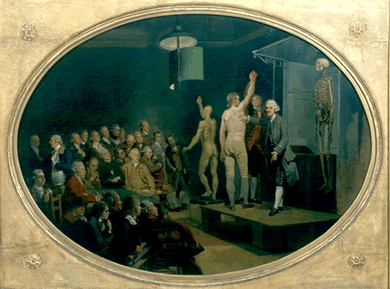

. London-based artists and writers included Thomas Gainsborough

Thomas Gainsborough (; 14 May 1727 (baptised) – 2 August 1788) was an English portrait and landscape painter, draughtsman, and printmaker. Along with his rival Sir Joshua Reynolds, he is considered one of the most important British artists o ...

, William Hogarth

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraving, engraver, pictorial social satire, satirist, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from Realism (visual arts), realistic p ...

, Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish writer, essayist, satirist, and Anglican cleric. In 1713, he became the Dean (Christianity), dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, and was given the sobriquet "Dean Swi ...

, Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft ( , ; 27 April 175910 September 1797) was an English writer and philosopher best known for her advocacy of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional ...

, and Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson ( – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

.

London's economy was massively boosted by its shipping industry, but other important industries included silkweaving. Many modern-day businesses trace their origins back to 18th-century London, including Sotheby's

Sotheby's ( ) is a British-founded multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine art, fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, an ...

, WHSmith

WH Smith plc, trading as WHSmith (also written WH Smith and formerly as W. H. Smith & Son), is a British retailer, with headquarters in Swindon, England, which operates a chain of railway station, airport, port, hospital and motorway service s ...

, and Schweppes

Schweppes ( , ) is a soft drink brand founded in the Republic of Geneva in 1783 by the German watchmaker and amateur scientist Johann Jacob Schweppe; it is now made, bottled, and distributed worldwide by multiple international conglomerates, de ...

. In order to transport goods and people, many new turnpikes and canals were constructed, and educational movements aimed at working-class children, such as Sunday school

]

A Sunday school, sometimes known as a Sabbath school, is an educational institution, usually Christianity, Christian in character and intended for children or neophytes.

Sunday school classes usually precede a Sunday church service and are u ...

s, were pioneered in this period.

Demography

At the beginning of the period, about 500,000 people lived in London. By 1713, this number had risen to 630,000; by 1760, it was 740,000, and by the end of the century, it was just over 1 million. The average height of a male Londoner was and the average height of a female Londoner was .Immigrant and disapora communities

African and Afro-Caribbean Londoners

In 1768, the abolitionistGranville Sharp

Granville Sharp (10 November 1735 – 6 July 1813) was an English scholar, philanthropist and one of the first campaigners for the Abolitionism in the United Kingdom, abolition of the slave trade in Britain. Born in Durham, England, Durham, he ...

estimated that there were 20,000 black people in domestic service in London. This included some who were enslaved, as evidenced by "for sale" or "runaway" notices in London newspapers. In the aftermath of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

in the 1780s, there was a small influx of black Americans who had fought for the British and were therefore no longer welcome in the United States, many of whom become homeless. Some black Londoners became well known through their writings, such as Ignatius Sancho

Charles Ignatius Sancho ( – 14 December 1780) was a British Abolitionism, abolitionist, writer and composer. Considered to have been born on a British slave ship in the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Sancho was sold by the British slave traders in ...

, Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano (; c. 1745 – 31 March 1797), known for most of his life as Gustavus Vassa (), was a writer and abolitionist. According to his memoir, he was from the village of Essaka in present day southern Nigeria. Enslaved as a child in ...

, Ottobah Cugoano

Ottobah Cugoano ( – ), also known as John Stuart, was a British abolitionist and activist who was born in the Gold Coast (modern-day Ghana). He was sold into slavery at the age of thirteen and shipped to Grenada in the West Indies. In 1772, h ...

, Robert Wedderburn, Ukawsaw Gronniosaw

Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (c. 1705 – 28 September 1775), ''The Chester Chronicle, or Commercial Intelligencer'', Monday 2 October 1775. also known as James Albert, was an enslaved African man who is considered the first published African in Brit ...

, Ayuba Suleiman Diallo

Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (17011773), also known as Job Ben Solomon, was a prominent Fulani Muslim prince from West Africa who was kidnapped and trafficked to the Americas during the Atlantic slave trade, having previously owned and sold slaves hi ...

, and Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley Peters, also spelled Phyllis and Wheatly ( – December 5, 1784), was an American writer who is considered the first African-American author of a published book of poetry. Gates Jr., Henry Louis, ''Trials of Phillis Wheatley: ...

. Other famous black figures of the day include the violinist George Bridgetower

George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower (11 October 1778 – 29 February 1860) was a British musician, of African and Polish descent. He was a virtuoso violinist who lived in England for much of his life. His playing impressed Beethoven, who ...

, the fencing master Julius Soubise

Julius Soubise (c. 1754 – 25 August 1798) was a formerly enslaved Afro-Caribbean man and a well-known fop in late eighteenth-century Britain. The satirized depiction of Soubise, ''A Mungo Macaroni'', is a relic of intersectionality between ra ...

, and the aristocrats Dido Belle and William Ansah Sessarakoo

William Ansah Sessarakoo ( 1736 – 1770), a prominent 18th-century Fante royal and diplomat, best known for his enslavement in the West Indies and diplomatic mission to England. He was both prominent among the Fante people and influential among ...

.

Asian Londoners

Around the docks in the East End was a population of sailors from India and east Asia known as "lascar

A lascar was a sailor or militiaman from the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, the Arab world, British Somaliland or other lands east of the Cape of Good Hope who was employed on European ships from the 16th century until the mid-20th centur ...

s" employed on ships belonging to the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

. The company ran a boarding house for them called Orchard House

Orchard House is a historic house museum in Concord, Massachusetts, United States, opened to the public on May 27, 1912. It was the longtime home of Amos Bronson Alcott (1799–1888) and his family, including his daughter Louisa May Alcott (183 ...

in Blackwall. In the wealthier West End of London, Indians were more likely to be employed as domestic servants by officers and former officers of the East India Company. In 1765, the ''munshi

During the Mughal Empire, ''Munshi'' () came to be used as a respected title for persons who achieved mastery over language and politics in the Indian subcontinent. Use in Bengal

The surname "Munshi" ( Bengali: মুন্সি) is used by bot ...

'' Mirza Sheikh I'tesamuddin became the first-known educated Indian to visit London. He wrote a book in Persian on his experiences in Europe which was later translated into English by James Edward Alexander.

European Londoners

London had populations of immigrants from various European countries. After the rights of French Protestants calledHuguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

were repealed in 1688, thousands fled to London. At the beginning of the period, there were an estimated 25,000 Huguenots in London, particularly in Soho

SoHo, short for "South of Houston Street, Houston Street", is a neighborhood in Lower Manhattan, New York City. Since the 1970s, the neighborhood has been the location of many artists' lofts and art galleries, art installations such as The Wall ...

and Spitalfields

Spitalfields () is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in East London and situated in the East End of London, East End. Spitalfields is formed around Commercial Street, London, Commercial Stre ...

. At their height, there were 23 French churches in London. Successful Huguenots included the sculptor Louis François Roubiliac and the optician John Dollond

John Dollond (30 November 1761) was an English optician, known for his successful optics business and his patenting and commercialization of achromatic doublets.

Biography

Dollond was the son of a Huguenot refugee, a silk-weaver at Spitalfie ...

. There was also a community of French Catholic immigrants, who ran French-language newspapers such as the ''Courier Politique et Littéraire'' and the ''Courier de Londres''. Well-known Londoners from other European countries include the painters Godfrey Kneller

Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1st Baronet (born Gottfried Kniller; 8 August 1646 – 19 October 1723) was a German-born British painter. The leading Portrait painting, portraitist in England during the late Stuart period, Stuart and early Georgian eras ...

, and Johan Zoffany

Johan / Johann Joseph Zoffany (born Johannes Josephus Zaufallij; 13 March 1733 – 11 November 1810) was a German Neoclassicism, neoclassical painter who was active mainly in England, Italy, and India. His works appear in many prominent Briti ...

; and the sculptors Peter Scheemakers

Peter Scheemakers or Pieter Scheemaeckers II or the Younger (10 January 1691 – 12 September 1781) was a Southern Netherlands, Flemish sculptor who worked for most of his life in London. His public and church sculptures in a classicism, classici ...

, Michael Rysbrack

Johannes Michel or John Michael Rysbrack, original name Jan Michiel Rijsbrack, often referred to simply as Michael Rysbrack (24 June 1694 – 8 January 1770), was an 18th-century Flemings, Flemish sculpture, sculptor, who spent most of his caree ...

and Giuseppe Ceracchi

Giuseppe Ceracchi, also known as ''Giuseppe Cirachi'', (4 July 1751 – 30 January 1801) was an Italian sculptor active in a Neoclassic style. He worked in Italy, England, and in the United States following the nation's emergence following the Am ...

. In 1750, a population of the Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

n Protestant sect called Moravians

Moravians ( or Colloquialism, colloquially , outdated ) are a West Slavs, West Slavic ethnic group from the Moravia region of the Czech Republic, who speak the Moravian dialects of Czech language, Czech or Czech language#Common Czech, Common ...

settled on Cheyne Walk

Cheyne Walk is a historic road in Chelsea, London, England, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. It runs parallel with the River Thames. Before the construction of Chelsea Embankment reduced the width of the Thames here, it fronted t ...

in Chelsea. They established a Moravian church and burial ground.

An estimated 30,000 Irish immigrants lived in London by the end of the period. Some were particularly successful, including Robert Barker Robert Barker may refer to:

Politicians

* Robert Barker (MP for Ipswich) (died 1571), English MP for Ipswich

* Robert Barker (MP for Thetford), English MP for Thetford

* Robert Barker (MP for Colchester) (1563–1618), English MP for Colchester

...

, Hans Sloane

Sir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet, (16 April 1660 – 11 January 1753), was an Irish physician, naturalist, and collector. He had a collection of 71,000 items which he bequeathed to the British nation, thus providing the foundation of the British ...

, James Barry, Charles Macklin

Charles Macklin (26 September 1699 – 11 July 1797), (Gaelic: Cathal MacLochlainn, English: Charles McLaughlin), was an Irish actor and dramatist who performed extensively at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Macklin revolutionised theatre in ...

, Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish writer, essayist, satirist, and Anglican cleric. In 1713, he became the Dean (Christianity), dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, and was given the sobriquet "Dean Swi ...

, Laurence Sterne

Laurence Sterne (24 November 1713 – 18 March 1768) was an Anglo-Irish novelist and Anglican cleric. He is best known for his comic novels ''The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman'' (1759–1767) and ''A Sentimental Journey Thro ...

, Oliver Goldsmith

Oliver Goldsmith (10 November 1728 – 4 April 1774) was an Anglo-Irish people, Anglo-Irish poet, novelist, playwright, and hack writer. A prolific author of various literature, he is regarded among the most versatile writers of the Georgian e ...

, and Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (30 October 17517 July 1816) was an Anglo-Irish playwright, writer and Whig politician who sat in the British House of Commons from 1780 to 1812, representing the constituencies of Stafford, Westminster and I ...

.

Theoretically, Romani people

{{Infobox ethnic group

, group = Romani people

, image =

, image_caption =

, flag = Roma flag.svg

, flag_caption = Romani flag created in 1933 and accepted at the 1971 World Romani Congress

, po ...

and travellers had been expelled from England since the 1560s, but there was nonetheless a community in London in the 18th century, particularly in Norwood. They were particularly associated with horse dealing and fortune-telling at London's fairs. Well-known travellers of the period included Jacob Rewbrey of Westminster, Margaret Finch of Norwood, and Diana Boswell from Dulwich

Dulwich (; ) is an area in south London, England. The settlement is mostly in the London Borough of Southwark, with parts in the London Borough of Lambeth, and consists of Dulwich Village, East Dulwich, West Dulwich, and the Southwark half of H ...

.

Historian Jerry White estimates that there were about 750 Jewish people living in London at the beginning of the period. By the end of the century, that number had risen to about 15,000. In 1701, Bevis Marks synagogue

Bevis Marks Synagogue, officially Qahal Kadosh Sha'ar ha-Shamayim (), is an Orthodox Judaism, Orthodox Judaism, Jewish congregation and synagogue, located off Bevis Marks, Aldgate, in the City of London, England, in the United Kingdom. The congr ...

opened to cater to Sephardic

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

Jews descended from Spanish and Portuguese immigrants. It is still a working synagogue to this day. Ashkenazi

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim) form a distinct subgroup of the Jewish diaspora, that Ethnogenesis, emerged in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium Common era, CE. They traditionally spe ...

Jews, descended from Dutch, German and central European immigrants, used the Great Synagogue in Duke's Place, the Hambro' Synagogue off Fenchurch Street

Fenchurch Street is a street in London, England, linking Aldgate at its eastern end with Lombard Street and Gracechurch Street in the west. It is a well-known thoroughfare in the City of London financial district and is the site of many cor ...

, and the New Synagogue on Leadenhall Street

__NOTOC__

Leadenhall Street () is a street in the City of London. It is about and links Cornhill, London, Cornhill in the west to Aldgate in the east. It was formerly the start of the A11 road (England), A11 road from London to Norwich, but th ...

. Practising Jews could not join the city's trade guilds, and so many Jewish business owners lived outside the city, in places like Aldgate

Aldgate () was a gate in the former defensive wall around the City of London.

The gate gave its name to ''Aldgate High Street'', the first stretch of the A11 road, that takes that name as it passes through the ancient, extramural Portsoken ...

and Whitechapel

Whitechapel () is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. It is the location of Tower Hamlets Town Hall and therefore the borough tow ...

. Michael Leoni was a famous Jewish singer, and Daniel Mendoza

Daniel Mendoza (5 July 1764 – 3 September 1836) (often known as Dan Mendoza) was an English prize fighter in the 1780s and 90s, and was also an instructor of pugilism. He was Sephardic of Portuguese Jewish descent.''The Jewish Boxer's Hall o ...

a famous Jewish boxer.

There were smaller numbers of people who came from further afield, such as Mehemet von Königstreu and Ernst August Mustapha, Turkish valets to George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George of Beltan (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgoruk ...

.

Other visitors

London also drew in people from all over the globe, even if they only visited for a short time. Examples include the Native American chiefTomochichi

Tomochichi (to-mo-chi-chi') (c. 1644 – October 5, 1741) was the head chief of a Yamacraw town on the site of present-day Savannah, Georgia, in the 18th century. He gave land on Yamacraw Bluff to James Oglethorpe to build the city of Savannah ...

and his retinue, who met George II in 1734; the Raiatean man Mai

Mai, or MAI, may refer to:

Names

* Mai (Chinese surname)

* Mai (Vietnamese surname)

* Mai (name)

* Mai (singer), J-Pop singer

Places

* Chiang Mai, largest city in northern Thailand

* Ma-i, a pre-Hispanic Philippine state

* Mai, Non Sung, Tha ...

, who visited in 1774 and had his portrait painted by the artist Joshua Reynolds; and the Aboriginal Australians Bennelong

Woollarawarre Bennelong ( 1764 – 3 January 1813) was a senior man of the Eora, an Aboriginal Australian people of the Port Jackson area, at the time of the first British settlement in Australia. Bennelong served as an interlocutor between ...

and Yemmerrawanne

Yemmerrawanne ( - 18 May 1794) was a member of the Wangal clan, part of the Dharug people in the Port Jackson area at the time of the first British settlement in Australia, in 1788. Along with another Aboriginal man, Bennelong, he accompani ...

, who visited in 1793.

Topography

Extent

London's growth in the 18th century was marked above all by the westward shift of the population away from theCity of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

. Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

was intensively developed, with new districts like Mayfair

Mayfair is an area of Westminster, London, England, in the City of Westminster. It is in Central London and part of the West End. It is between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane and one of the most expensive districts ...

housing Britain's wealthiest aristocratic families. Cavendish Square

Cavendish Square is a public square, public garden square in Marylebone in the West End of London. It has a double-helix underground commercial car park. Its northern road forms ends of four streets: of Wigmore Street that runs to Portman Square ...

and Hanover Square were both laid out in the 1710s, while the Portman Estate Portman may refer to:

* Portman (surname)

* Viscount Portman

Places

* Portmán, a town near Cartagena, Spain

* Orchard Portman, a village and civil parish in Somerset, England

* Portman Estate, 110 acres in Marylebone in London’s West End

* Por ...

, which occupies the western half of Marylebone, began its own building program in the 1750s with the granting of commercial leases, followed by the commencement of building on Portman Square

Portman Square is a garden square in Marylebone, central London, surrounded by townhouses. It was specifically for private housing let on long leases having a ground rent by the Portman Estate, which owns the private communal gardens. It mar ...

in 1764. Manchester Square

Manchester Square is an 18th-century garden square in Marylebone, central London. Centred north of Oxford Street it measures internally north-to-south, and across. It is a small Georgian square, predominantly 1770s-designed. Construction ...

was begun in 1776. Comparison of London maps made in the mid-17th century with ones made in the mid-18th century also reveal that the new developments were much more likely to be built along grid structures.

The most exclusive area, Mayfair, was intensively built up with luxury townhouses on an area occupied by seven different estates: the Grosvenor

Grosvenor may refer to:

People

* Grosvenor (surname), including a list of people with the surname Grosvenor

* Grosvenor Francis (1873–1944), Australian politician

* Grosvenor Hodgkinson (1818–1881), English lawyer and politician

Places, ...

, Burlington, Berkeley, Curzon, Milfield, Conduit Mead, and Albemarle Ground estates. The Grosvenor estate

Grosvenor Group Limited is an internationally diversified property group, which traces its origins to 1677 and has its headquarters in London, England. Previously (from 1841) based at 66-68 Brook Street & 53 Davies Street, it is now based at 7 ...

, in the northwest corner between Oxford Street and Park Lane, was the most substantial private plot of land, featuring an orderly grid network of streets constructed around Grosvenor Square

Grosvenor Square ( ) is a large garden square in the Mayfair district of Westminster, Greater London. It is the centrepiece of the Mayfair property of the Duke of Westminster, and takes its name from the duke's surname "Grosvenor". It was deve ...

in the early 1720s. By 1738 "nearly the whole space between Piccadilly and Oxford Street was covered with buildings as far as Tyburn Lane ark Lane except in the south-western corner about Berkeley Square and Mayfair". Further west, the Cadogan Estate

Cadogan Group Limited and its subsidiaries, including Cadogan Estates Limited, are British property investment and management companies that are owned by the Cadogan family, one of the richest families in the United Kingdom. They also hold the ...

began working on the area between Knightsbridge

Knightsbridge is a residential and retail district in central London, south of Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park. It is identified in the London Plan as one of two international retail centres in London, alongside the West End of London, West End. ...

and Sloane Square

Sloane Square is a small hard-landscaped square on the boundaries of the central London districts of Belgravia and Chelsea, London, Chelsea, located southwest of Charing Cross, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The area forms a ...

in 1777.

To the south, the area now known as Elephant & Castle

Elephant and Castle is an area of South London, England, in the London Borough of Southwark. The name also informally refers to much of Walworth and Newington, due to the proximity of the London Underground station of the same name. The nam ...

was also laid out in this period, with a road from Westminster Bridge connecting up to Borough High Street

Borough High Street is a road in Southwark, London, running south-west from London Bridge, forming part of the A3 road, A3 route which runs from London to Portsmouth, on the south coast of England.

Overview

Borough High Street continues sout ...

, and the New Kent Road

New Kent Road is a road in the London Borough of Southwark. The road was created in 1751 when the Turnpike trust, Turnpike Trust upgraded a local footpath. This was done as part of the general road improvements associated with the creation o ...

also constructed. To the north, new developments sprang up around between Paddington and Islington such as Pentonville

Pentonville is an area in North London, located in the London Borough of Islington. It is located north-northeast of Charing Cross on the London Inner Ring Road, Inner Ring Road. Pentonville developed in the northwestern edge of the ancient p ...

, named after its landlord, Henry Penton; and Somers Town, named after its landlord, Charles Cocks, 1st Baron Somers

Charles Cocks, 1st Baron Somers (29 June 1725 – 30 January 1806), known as Sir Charles Cocks, 1st Baronet, from 1772 to 1784, was a British politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1747 to 1784.

Life

Cocks was the son of John Cocks and ...

. Construction began on Bedford Square

Bedford Square is a garden square in the Bloomsbury district of the London Borough of Camden, Borough of Camden in London, England.

History

Built between 1775 and 1783 as an upper middle class residential area, the square has had many disti ...

in 1775, which has been called "the most perfect of the London squares of the period", and Finsbury Square

Finsbury Square is a square in Finsbury in central London which includes a six-rink grass bowling green. It was developed in 1777 on the site of a previous area of green space to the north of the City of London known as Finsbury Fields, in the p ...

was begun in 1777. Building started on Camden Town

Camden Town () is an area in the London Borough of Camden, around north-northwest of Charing Cross. Historically in Middlesex, it is identified in the London Plan as one of 34 major centres in Greater London.

Laid out as a residential distri ...

in 1791, named after the 1st Earl Camden.

Rural villages surrounding Westminster and the city also grew in population and were gradually incorporated into the metropolis: areas like Bethnal Green

Bethnal Green is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. The area emerged from the small settlement which developed around the common la ...

and Shadwell

Shadwell is an area in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London, England. It also forms part of the city's East End of London, East End. Shadwell is on the north bank of the River Thames between Wapping (to the west) and Ratcliff and ...

to the east, or Paddington

Paddington is an area in the City of Westminster, in central London, England. A medieval parish then a metropolitan borough of the County of London, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Paddington station, designed b ...

and St. Pancras to the northwest. In 1750 the London topographer John Noorthouck

John Noorthouck (1732–1816) was an English author, best known as a topographer of London.

Life

Born in London, he was the son of Herman Noorthouck, a bookseller who had a shop, the Cicero's Head, Great Piazza, Covent Garden, and whose stock was ...

reckoned that London proper consisted of 46 former villages, two cities (Westminster and the City of London proper), and one borough (Southwark). Westminster had a population of 162,077, the City 116,755, and Southwark 61,169.

New buildings

New mansions built in this period include

New mansions built in this period include Burgh House

Burgh House is a historic house located on New End Square in Hampstead, London, that includes the Hampstead Museum. The house is also listed as Burgh House & Hampstead Museum.

Brief history

Burgh House was constructed in 1704 during the r ...

in Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, England, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, located mainly in the London Borough of Camden, with a small part in the London Borough of Barnet. It borders Highgate and Golders Green to the north, Belsiz ...

(1703), Buckingham House (1705), Marlborough House

Marlborough House, a Grade I listed mansion on The Mall in St James's, City of Westminster, London, is the headquarters of the Commonwealth of Nations and the seat of the Commonwealth Secretariat. It is adjacent to St James's Palace.

The ...

(begun 1709), Marble Hill

Marble Hill is the name of:

Australia

*Marble Hill, South Australia, the vice-regal residence in the Adelaide Hills

Ireland

* Marble Hill, County Donegal, a village in County Donegal

United Kingdom

*Marble Hill House, a villa on the banks ...

and Chiswick House

Chiswick House is a Neo-Palladian style villa in the Chiswick district of London, England. A "glorious" example of Neo-Palladian architecture in west London, the house was designed and built by Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington (1694–1753 ...

(1729), Strawberry Hill Strawberry Hill may refer to:

United Kingdom

*Strawberry Hill, London, England

**Strawberry Hill House, Horace Walpole's Gothic revival villa

**Strawberry Hill railway station

* Strawberry Hill, a rewilded farm at Knotting Green, Bedfordshire

Uni ...

(begun 1747), Spencer House Spencer House may refer to:

* Spencer House, Westminster, Greater London, England

United States

* Spencer House (Hartford, Connecticut), listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in Hartford County

* Spencer House in Columbus, ...

(competed 1766), Albany (1770), Home House

Home House is a Georgian town house at 20 Portman Square, London. James Wyatt was appointed to design it by Elizabeth, Countess of Home in 1776, but by 1777 he had been dismissed and replaced by Robert Adam. Elizabeth left the completed h ...

(completed 1776), Apsley House

Apsley House is the London townhouse of the Dukes of Wellington. It stands alone at Hyde Park Corner, on the south-east corner of Hyde Park, facing towards the large traffic roundabout in the centre of which stands the Wellington Arch. It ...

(completed 1778), and Dover House

Dover House is a Grade I-listed mansion in Whitehall, and the London headquarters of the Scotland Office. The building also houses the Office of the Advocate General for Scotland and the Independent Commission for Aid Impact.

History

Dover H ...

(completed 1787). Buckingham House, later known as Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

, was bought by George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

in 1762. In 1783, work began on expanding and renovating Carlton House

Carlton House, sometimes Carlton Palace, was a mansion in Westminster, best known as the town residence of George IV, during the regency era and his time as prince regent, before he took the throne as king. It faced the south side of Pall M ...

for the then Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

, which took years to be completed as well as huge amounts of taxpayer money, only for the Prince to live there for a very short amount of time.

In 1732, part of no. 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street in London is the official residence and office of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister of the United Kingdom. Colloquially known as Number 10, the building is located in Downing Street, off Whitehall in th ...

was acquired by the Crown and offered to the Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (; 26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745), known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British Whigs (British political party), Whig statesman who is generally regarded as the ''de facto'' first Prim ...

. As he already had many houses and didn't want to pay to upkeep another, he accepted it as a perk of his position, beginning the tradition of passing the house down to each successive Prime Minister. It was substantially remodelled by the architect William Kent

William Kent (c. 1685 – 12 April 1748) was an English architect, landscape architect, painter and furniture designer of the early 18th century. He began his career as a painter, and became Principal Painter in Ordinary or court painter, b ...

. The residence of the Lord Mayor of the City of London

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

, Mansion House, was completed in 1753 after having been designed by architect George Dance the Elder

George Dance the Elder (1695 – 8 February 1768) was a British architect. He was the City of London Surveyor (surveying), surveyor and architect from 1735 until his death.

Life

Originally a mason, George Dance was appointed Clerk of the ci ...

. The current Treasury building was completed in 1736.

Bevis Marks Synagogue was one of the first new religious buildings of the period, opening in 1701. In 1710, the final stone was added to St. Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

, designed by Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren FRS (; – ) was an English architect, astronomer, mathematician and physicist who was one of the most highly acclaimed architects in the history of England. Known for his work in the English Baroque style, he was ac ...

. This cathedral replaced Old St. Paul's, which had been completely destroyed in the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Wednesday 5 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old London Wall, Roman city wall, while also extendi ...

. A flurry of church-building between 1711 and 1730 also saw the construction of Christ Church Spitalfields

Christ Church Spitalfields is an Anglican church built between 1714 and 1729 to a design by Nicholas Hawksmoor. On Commercial Street in the East End and in today's Central London it is in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, on its western bor ...

, St. Anne's Limehouse, St. George in the East, St. George's Bloomsbury, St. Mary Woolnoth, St. Mary-le-Strand, St. Paul's Deptford, St. Giles-in-the-Fields

St Giles in the Fields is the Anglican parish church of the St Giles district of London. The parish stands within the London Borough of Camden and forms part of the Diocese of London. The church, named for St Giles the Hermit, began as the c ...

, St. George's Hanover Square, St. Anne's Kew, St. Botolph-without-Bishopsgate, St. Mary's Rotherhithe, St. Peter's Vere Street, St. Martin-in-the-Fields, St. John's Smith Square, and Grosvenor Chapel

Grosvenor Chapel is an Anglican church in what is now the City of Westminster, in England, built in the 1730s. It inspired many churches in New England. It is situated on South Audley Street in Mayfair.

History

The foundation stone of the Grosve ...

. After this, further churches built in the period include St. George the Martyr, Southwark (1736), St. Mary's Ealing (1740), St. John-at-Hampstead (1747), Wesley's Chapel

Wesley's Chapel (originally the City Road Chapel) is a Methodist Church of Great Britain, Methodist church situated in the St Luke's, London, St Luke's area in the south of the London Borough of Islington. Opened in 1778, it was built under the ...

(1756), and the Portland Chapel (1766). Another burst of church-building occurred towards the end of the period, with new churches such as St. Mary's Paddington, St. James's Clerkenwell, and St. Patrick's Soho Square (1792), St. John-at-Hackney and St. Martin Outwich (1798).

The period also saw the construction of several bridges across the Thames alongside London Bridge

The name "London Bridge" refers to several historic crossings that have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark in central London since Roman Britain, Roman times. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 197 ...

. With the completion of Westminster Bridge

Westminster Bridge is a road-and-foot-traffic bridge crossing over the River Thames in London, linking Westminster on the west side and Lambeth on the east side.

The bridge is painted predominantly green, the same colour as the leather seats ...

in 1750, London gained a much needed second crossing onto the south bank, and Blackfriars Bridge

Blackfriars Bridge is a road and foot traffic bridge over the River Thames in London, between Waterloo Bridge and Blackfriars Railway Bridge, carrying the A201 road. The north end is in the City of London near the Inns of Court and Temple C ...

opened in 1769. To the west, Putney Bridge

Putney Bridge is a Grade II listed bridge over the River Thames in west London, linking Putney on the south side with Fulham to the north. Before the first bridge was built in 1729, a ferry had shuttled between the two banks.

The current for ...

was built in 1729, Kew

Kew () is a district in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Its population at the 2011 census was 11,436. Kew is the location of the Royal Botanic Gardens ("Kew Gardens"), now a World Heritage Site, which includes Kew Palace. Kew is ...

built its first bridge in 1759, and Richmond Bridge opened in 1777.

The first Freemasons' Hall was built on Great Queen Street

Great Queen Street is a street in the West End of central London in England. It is a continuation of Long Acre from Drury Lane to Kingsway. It runs from 1 to 44 along the north side, east to west, and 45 to about 80 along the south side, wes ...

in 1776. Severndroog Castle

Severndroog Castle is a folly designed by architect Richard Jupp, with the first stone laid on 2 April 1784.

While commonly referred to as a castle due to its turrets, it was built as a folly, as can be discerned by its small size and because it ...

was built in 1784 to commemorate the seagoing victories of Sir William James, who had died the previous year. Trinity House

The Corporation of Trinity House of Deptford Strond, also known as Trinity House (and formally as The Master, Wardens and Assistants of the Guild Fraternity or Brotherhood of the most glorious and undivided Trinity and of St Clement in the ...

was built for the body that governs English and Welsh lighthouses in 1795. Shop fronts also began to be built with large windows for passers-by to see the goods inside, examples of which can still be seen at 88 Dean Street

Dean Street is a street in Soho, central London, running from Oxford Street south to Shaftesbury Avenue. It crosses Old Compton Street and is linked to Frith Street by Bateman Street.

Culture

The Soho Theatre presents new plays and stand-u ...

and James Lock & Co

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

on St. James's Street

St James's Street is the principal street in the district of St James's, central London. It runs from Piccadilly downhill to St James's Palace and Pall Mall. The main gatehouse of the Palace is at the southern end of the road; in the 17th centu ...

. New government offices included Somerset House

Somerset House is a large neoclassical architecture, neoclassical building complex situated on the south side of the Strand, London, Strand in central London, overlooking the River Thames, just east of Waterloo Bridge. The Georgian era quadran ...

, the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Tra ...

, and Horse Guards.

Urban fabric

To accommodate the rapid growth of population, Parliament enacted building legislation and initiated important infrastructure projects. The Fleet River, which was so filled with rubbish and sewage that it had been a health hazard for many years, was finally covered over in 1733. The New Road running between Paddington and Islington was constructed beginning in 1756. Intended as adrover's road

A drovers' road, drove road, droveway, or simply a drove, is a route for droving livestock on foot from one place to another, such as to market or between summer and winter pasture (see transhumance). Many drovers' roads were ancient routes of ...

upon which livestock could be driven to Smithfield Market

Smithfield, properly known as West Smithfield, is a district located in Central London, part of Farringdon Without, the most westerly Wards of the City of London, ward of the City of London, England.

Smithfield is home to a number of City in ...

without encountering the congested road network of the city further south, the wide New Road was London's first bypass and served as the informal northern boundary for London for years to come. The City Road

City Road or The City Road is a road that runs through central London. The northwestern extremity of the road is at Angel where it forms a continuation of Pentonville Road. Pentonville Road itself is the modern name for the eastern part of Lo ...

was added in 1761, connecting the Angel

Angels are a type of creature present in many mythologies.

Angel or Angels may refer to:

Places

* Angel (river), in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

* Angel, London, an area of London

** Angel tube station

** The Angel, Islington, a building from ...

to Finsbury Square

Finsbury Square is a square in Finsbury in central London which includes a six-rink grass bowling green. It was developed in 1777 on the site of a previous area of green space to the north of the City of London known as Finsbury Fields, in the p ...

. To improve traffic, the houses on London Bridge

The name "London Bridge" refers to several historic crossings that have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark in central London since Roman Britain, Roman times. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 197 ...

were removed in 1757, the Holbein Gate

The Holbein Gate was a monumental gateway across Whitehall in Westminster, constructed in 1531–32 in the English Gothic style. The Holbein Gate and a second less ornate gate, Westminster Gate, were constructed by Henry VIII to connect parts ...

in Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

was removed in 1759, and the gates of the city were removed 1760–1777.

From 1707, buildings in London were no longer permitted with upper storeys overhanging the lower ones, so facades on future buildings were strictly vertical. After the Building Regulation Act 1709 (7 Ann.

This is a complete list of acts of the Parliament of Great Britain for the year 1708.

For acts passed until 1707, see the list of acts of the Parliament of England and the list of acts of the Parliament of Scotland. See also the list of acts o ...

c. 17), wooden window frames were required to be recessed at least 4 inches into the wall to prevent the spread of fire up a building's facade. In 1762, shop signs that hung down were banned in the City and Westminster, and had to be fixed flat to the building instead to prevent them blocking out sunlight and falling on people walking underneath. The Building Act 1777 set building requirements for new housing and sought to eliminate rampant jerry-building and shoddy construction work. Housing was divided into four "rates" based on ground rents, with each of the rates accorded their own strict building codes. The Building Act accounts for the remarkable uniformity of Georgian terraced housing and squares in London built in subsequent decades, which critics like John Summerson

Sir John Newenham Summerson (25 November 1904 – 10 November 1992) was one of the leading British architectural historians of the 20th century.

Early life

John Summerson was born at Barnstead, Coniscliffe Road, Darlington. His grandfather wo ...

criticized for their "inexpressible monotony".

Landmark legislation included the Westminster Paving Act 1765 (5 Geo. 3

This is a complete list of acts of the Parliament of Great Britain for the year 1765.

For acts passed until 1707, see the list of acts of the Parliament of England and the list of acts of the Parliament of Scotland. See also the list of acts of ...

. c. 50), which required streets be equipped with pavements, drainage, and lighting. The success of the legislation inspired the London Paving and Lighting Act 1766 ( 6 Geo. 3. c. 26), which extended the same provisions across the whole city and required that houses be numbered and streets and pavements be cleansed and swept regularly. Street lighting was more extensive than in any other city in Europe, something which amazed foreign visitors to the capital in the late 18th century. The practice of numbering houses also dates from this period, with some sources claiming it started in New Burlington Street

New Burlington Street (originally Little Burlington Street) is a street in central London that is on land that was once part of the Burlington Estate. The current architecture of the street bears little resemblance to the original design of the ...

. The practice of putting street names on signs at each corner was taken up by the city from 1765 onwards.

Crime and law enforcement

Armed robbery was particularly common in London, either byhighwaymen

A highwayman was a robber who stole from travellers. This type of thief usually travelled and robbed by horse as compared to a footpad who travelled and robbed on foot; mounted highwaymen were widely considered to be socially superior to foo ...

(on horseback) or footpad

In archaic terminology, a footpad is a robber or thief specialising in pedestrian victims. The term was used widely from the 16th century until the 19th century, but gradually fell out of common use. A footpad was considered a low criminal, as op ...

s (on foot). One gang, run by a man called Obadiah Lemon, used fishing hoods to steal hats and wigs through open coach windows, or leapt on top and cut through the roof. George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

himself was robbed of his shoe buckles and spare change while walking in Kensington Gardens

Kensington Gardens, once the private gardens of Kensington Palace, are among the Royal Parks of London. The gardens are shared by the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and sit immediately to the west of Hyde Pa ...

. During the 1750s, several outyling towns in London's suburbs organised their own guard patrols to combat robbers on their roads. For example, Blackheath residents offered rewards for information on highwaymen in 1753, and Kentish Town

Kentish Town is an area of northwest London, England, in the London Borough of Camden, immediately north of Camden Town, close to Hampstead Heath.

Kentish Town likely derives its name from Ken-ditch or Caen-ditch, meaning the "bed of a waterw ...

inhabitants paid to hire guards in 1756.

Pickpocketing was also particularly common in London, where large crowds often gathered at executions and theatre performances. There was also large amounts of theft on the river, as ships laden with valuable goods waited with skeleton crews for a berth in the Pool of London

The Pool of London is a stretch of the River Thames from London Bridge to below Limehouse.

Part of the Tideway of the Thames, the Pool was navigable by tall-masted vessels bringing coastal and later overseas goods—the wharves there were t ...

. £70,000 worth of sugar alone was stolen per year from boats on the river. Sex work was another common crime, particularly associated with Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

. In 1758, it was estimated that 3,000 sex workers lived in London. On one routine sweep, constables arrested 22 sex workers in Covent Garden, two of whom were men dressed as women. In 1757, a catalogue of London's sex workers was published called ''Harris's List of Covent Garden Ladies

''Harris's List of Covent Garden Ladies'', published from 1760 to 1794, was an annual directory of prostitutes then working in Georgian era, Georgian London. A small pocketbook, it was printed and published in Covent Garden, and sold ...

'', which detailed the names, locations, and descriptions of hundreds of workers in the capital.

Although the crime of buggery was punishable by death, London had several establishments known as "molly house

Molly house or molly-house was a term used in 18th- and 19th-century Britain for a meeting place for homosexual men and gender-nonconforming people. The meeting places were generally taverns, public houses, coffeehouses or even private rooms ...

s", where queer men could meet. According to one homophobic pamphlet of the time, men in molly houses took on female personas and performed mock weddings and birth ceremonies. The 18th century saw a huge backlash against molly houses, with the publication of pamphlets such as ''The Sodomites' Shame and Doom'', and groups such as the Society for the Reformation of Manners

The Society for the Reformation of Manners was founded in the Tower Hamlets area of London in 1691.Mother Clap's in

Throughout the period, the number of crimes, especially

Throughout the period, the number of crimes, especially  After the

After the

The

The

Towards the end of the period,

Towards the end of the period,

1728 saw the opening of ''

1728 saw the opening of ''

In 1720,

In 1720,

King's Cross had several springs which were thought to have medicinal qualities. In 1759, the Bagnigge Wells opened, with a pump room where visitors could drink the water, play skittles, and hear concerts. Water could be bought for 3d per gallon. In 1770, a spa was also founded in

King's Cross had several springs which were thought to have medicinal qualities. In 1759, the Bagnigge Wells opened, with a pump room where visitors could drink the water, play skittles, and hear concerts. Water could be bought for 3d per gallon. In 1770, a spa was also founded in

Several long-standing London business trace their history back to this period, including the department store

Several long-standing London business trace their history back to this period, including the department store

Holborn

Holborn ( or ), an area in central London, covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn (parish), St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Wards of the City of London, Ward of Farringdon Without i ...

, which was raided in 1726, resulting in 40 arrests and three hangings. Mother Clap herself was sentenced to the pillory and two years in prison.

Law enforcement

There was no organised police force in this period. In times of serious emergency, or in the case of organised gangs, the authorities could deploy the military, but this was deeply unpopular, both with citizens and with the military themselves. There were small, specialised forces, such as the King's Messengers (who dealt with sedition, particularly Jacobites), the Press Messengers (who dealt with seditious publishers) and the City Marshals (localised to the City of London). Local magistrates, or Justices of the Peace, could issue warrants for criminals; and their officers, constables, would apprehend them. Constables were also responsible for policing low-level criminals such as sex workers and fortune tellers, detecting crime, and raising the "hue and cry

In common law, a hue and cry is a process by which bystanders are summoned to assist in the apprehension of a criminal who has been witnessed in the act of committing a crime.

History

By the Statute of Winchester of 1285, 13 Edw. 1. St. 2. c. ...

". Below them, beadle

A beadle, sometimes spelled bedel, is an official who may usher, keep order, make reports, and assist in religious functions; or a minor official who carries out various civil, educational or ceremonial duties on the manor.

The term has pre- ...

s were responsible for making sure that those who qualified for "outdoor relief

Outdoor relief, an obsolete term originating with the Elizabethan Poor Law (1601), was a programme of social welfare and poor relief. Assistance was given in the form of money, food, clothing or goods to alleviate poverty without the requirem ...

" were receiving it, acting as town crier

A town crier, also called a bellman, is an officer of a royal court or public authority who makes public pronouncements as required.

Duties and functions

The town crier was used to make public announcements in the streets. Criers often dre ...

, and supervising the town watch

A neighborhood watch or neighbourhood watch (see spelling differences), also called a crime watch or neighbourhood crime watch, is an organized group of civilians devoted to crime and vandalism prevention within a neighborhood.

The aim of ne ...

; and the watch patrolled the streets at night armed with a lantern and a cudgel to discourage crime. Corruption was endemic, meaning that if one wanted someone prosecuted, one had to do all the leg-work oneself, bribing officers at every stage. In previous eras, Londoners had been able to claim sanctuary at monasteries and former monasteries in order to avoid the law, but by 1712 this practice had been eradicated.

Bow Street Magistrates' Court

Bow Street Magistrates' Court (formerly Bow Street Magistrates' court (England and Wales), Police Court) and Police Station each became one of the most famous magistrates' court (England and Wales), magistrates' courts and police stations in Eng ...

opened in 1740 in Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

. One of the magistrates, Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English writer and magistrate known for the use of humour and satire in his works. His 1749 comic novel ''The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling'' was a seminal work in the genre. Along wi ...

, established the Bow Street Runners

The Bow Street Runners were the law enforcement officers of the Bow Street Magistrates' Court in the City of Westminster. They have been called London's first professional police force. The force originally numbered six men and was founded in 1 ...

in 1749 as an early form of a police force. They took the form of six parish constables who acted as bounty hunters, being paid a regular salary plus bonuses for any criminal they apprehended who was successfully prosecuted. The Bow Street Runners were unusual in that they are generally agreed to have not been corrupt. In 1754, John Fielding

Sir John Fielding (16 September 1721 – 4 September 1780) was an English magistrate and social reformer of the 18th century. He was the younger half-brother of novelist, playwright and chief magistrate Henry Fielding. Despite being blinded i ...

took over as chief magistrate, and his writings on the model popularised the concept across the country as he advocated for a national police force. Fielding is even credited with popularising the word "police". By the end of the century, there were eight or nine other such groups belonging to magistrates' courts around London.

Inspired by the Bow Street Runners, in 1798 Patrick Colquhoun

Patrick Colquhoun ( ; 14 March 1745 – 25 April 1820) was a Scottish merchant, statistician, magistrate, and founder of the first regular preventive police force in England, the Thames River Police. He also served as Lord Provost of Glasgow 1 ...

set up the River Police

Water police, also called bay constables, coastal police, harbor patrols, marine/maritime police/patrol, nautical patrols, port police, or river police are a specialty law enforcement portion of a larger police organization, who patrol in wate ...

, sometimes called the first professional police force in the country, which tackled crime in the docks and Pool of London

The Pool of London is a stretch of the River Thames from London Bridge to below Limehouse.

Part of the Tideway of the Thames, the Pool was navigable by tall-masted vessels bringing coastal and later overseas goods—the wharves there were t ...

.

Punishments

Throughout the period, the number of crimes, especially

Throughout the period, the number of crimes, especially property crime

Property crime is a category of crime, usually involving private property, that includes, among other crimes, burglary, larceny, theft, motor vehicle theft, arson, shoplifting, and vandalism. Property crime is a crime to obtain money, property, ...

s, subject to the death penalty ballooned under a period of English law known as the Bloody Code

The "Bloody Code" was a series of laws in England, Wales and Ireland in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries which mandated the death penalty for a wide range of crimes. It was not referred to by this name in its own time; the name was g ...

. Of those executions, London played host to the vast majority. Hanging

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

was a common punishment for several crimes. In the period 1750–1775, 3.85 people per 100,000 were hanged per year on average, and only 12% of these were for murder, as the number of people executed for property crimes grew under the Bloody Code. Hangings were public, and could attract large crowds depending on the fame of the victims. When the thief Jack Sheppard

John Sheppard (4 March 1702 – 16 November 1724), nicknamed "Honest Jack", was a notorious English thief and prison escapee of early 18th-century London.

Born into a poor family, he was apprenticed as a carpenter, but began committing thef ...

, who had escaped from prison multiple times, was finally hanged at Tyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in London, Middlesex, England, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone. Tyburn took its name from the Tyburn Brook, a tributary of the River Westbourne. The name Tyburn, from Teo Bourne ...

in 200,000 people reportedly came to see it. In the 1780s, the authorities stopped use of Tyburn as London's main execution site in favour of Newgate Prison. The last person executed at Tyburn was a man called John Austin in 1782. London employed a chief hangman and an assistant for this job, at a salary of £50 per year plus a guinea per execution. The most famous of these was John Price, who was himself hanged for murder in 1718. As an extra punishment for particularly cold-blooded crimes, a hanged body would be publicly displayed in chains, such as a Mrs Phipoe in 1797, whose body was displayed at the Old Bailey.

Pirates were generally hanged at Execution Dock

Execution Dock was a site on the River Thames near the shoreline at Wapping, London, that was used for more than 400 years to Execution (legal), execute Pirate, pirates, smugglers and mutiny, mutineers who had been sentenced to death by Admiralt ...

on the foreshore of the Thames near Brewhouse Lane and Wapping High Street, and the bodies would be left there until they had been covered by three tides of the river. This was done to Captain William Kidd in 1701. Burning at the stake

Death by burning is an execution, murder, or suicide method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment for and warning agai ...

was used as a punishment for women who committed treason, as in the case of Katherine Hayes, who was burned in 1726 at Tyburn for murdering her husband. As the period went on, this sentence changed to include being hanged before the body was burned at the stake. Men who committed treason were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered was a method of torture, torturous capital punishment used principally to execute men convicted of High treason in the United Kingdom, high treason in medieval and early modern Britain and Ireland. The convi ...

, as was the case for several soldiers who supported the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion

The Jacobite rising of 1745 was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took place during the War of the Austrian Succession, when the bulk of the British Army was fightin ...

, who were executed on Kennington Common

Kennington Common was a swathe of common land mainly within the London Borough of Lambeth. It was one of the earliest venues for cricket around London, with matches played between 1724 and 1785. G B Buckley, ''Fresh Light on 18th Century Cric ...

. Nobles who committed treason were permitted to die by beheading. The last person to be executed by beheading in Britain was Lord Lovat

Lord Lovat () is a title of the rank Lord of Parliament in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1458 for Hugh Fraser by summoning him to the Scottish Parliament as Lord Fraser of Lovat, although the holder is referred to simply as Lo ...

on Tower Hill

Tower Hill is the area surrounding the Tower of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is infamous for the public execution of high status prisoners from the late 14th to the mid 18th century. The execution site on the higher gro ...

in 1747. Prisoners who refused to plead either guilty or not guilty would be "pressed" to death, otherwise known as ''peine forte et dure

' ( Law French for "hard and forceful punishment") was a method of torture formerly used in the common law legal system, in which a defendant who refused to plead ("stood mute") would be subjected to having heavier and heavier stones placed upon ...

,'' by being slowly crushed by large stones, a practice abolished in 1772.

After the

After the Transportation Act 1717

The Piracy Act 1717 ( 4 Geo. 1. c. 11), sometimes called the Transportation Act 1717 or the Felons' Act 1717 (1718 in New Style), was an act of the Parliament of Great Britain that established a regulated, bonded system to transport crimina ...

, transportation

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional Motion, movement of humans, animals, and cargo, goods from one location to another. Mode of transport, Modes of transport include aviation, air, land tr ...

became another common punishment. At the beginning of the period, convicts were transported to the American colonies, where their labour would be sold to a plantation for the duration of their sentence, but after the American Revolutionary War, the authorities looked for a new location. London's first shipment of convicts to Australia set off in 1787, and landed in Port Jackson

Port Jackson, commonly known as Sydney Harbour, is a natural harbour on the east coast of Australia, around which Sydney was built. It consists of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta ...

, in modern-day Sydney. Some crimes were punished by whipping

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed on ...

, which could take place either in public, tied to the back of a cart and being marched through the streets; or in the private confines of a prison. Another punishment designed to inflict public humiliation was the pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, used during the medieval and renaissance periods for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. ...

. As the century went on, those sentenced to the pillory would increasingly find themselves at the mercy of the mob, who could either protect them while they served their sentence or throw rotten vegetables, manure, dead animals, or rocks. Several people were killed by mobs while in the pillory.

Prisons

At the beginning of the period, there were three kinds of prison in London: gaols such as that on Horsemonger Lane, where arrestees were kept prior to a trial;debtors' prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, Lucinda"A Histor ...

s such as Marshalsea

The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, just south of the River Thames. Although it housed a variety of prisoners—including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition—it became known, ...

; and houses of correction such as Bridewell Prison for the "reformation" of those who had no employment- often sex workers and the homeless. In 1779, a new kind of prison was introduced called the pentitentiary, with an emphasis on forcing criminals to do hard labour. In 1794, London gained a new prison at Coldbath Fields, where prisoners worked at occupations such as oakum-picking or walking on a treadmill, in silence, for ten hours a day

London's prisons were often filthy and its officers corrupt. In 1726, an investigation into conditions in the Fleet Prison

Fleet Prison was a notorious London prison by the side of the River Fleet. The prison was built in 1197, was rebuilt several times, and was in use until 1844. It was demolished in 1846.

History

The prison was built in 1197 off what is now ...

revealed that families had to bribe the warden to hand over the bodies of their family members who had died inside; and that one man called Jacob Solas had been chained up next to a sewer and a rubbish heap for two months. In 1750, an outbreak of "jail fever" at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

next to Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey, just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, the pr ...

killed at least 50 people.

War and uprisings

In 1715, claimant to the throne James Stuart landed in Scotland in what is known as theJacobite Rebellion

Jacobitism was a political ideology advocating the restoration of the senior line of the House of Stuart to the British throne. When James II of England chose exile after the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, the Parliament of England rule ...

. In London, his supporters rioted, burning a portrait of William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily ()