1876 Presidential Election on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

File:President Rutherford Hayes 1870 - 1880 Restored (cropped).jpg,

William A. Wheeler from New York File:Honorable_Hamilton_Fish_Brady-Handy.jpg, Secretary of State

Hamilton Fish from New York

(declined to run) File:UlyssesGrant.jpg,

(declined in 1875)

It was widely assumed during the year 1875 that incumbent President

It was widely assumed during the year 1875 that incumbent President

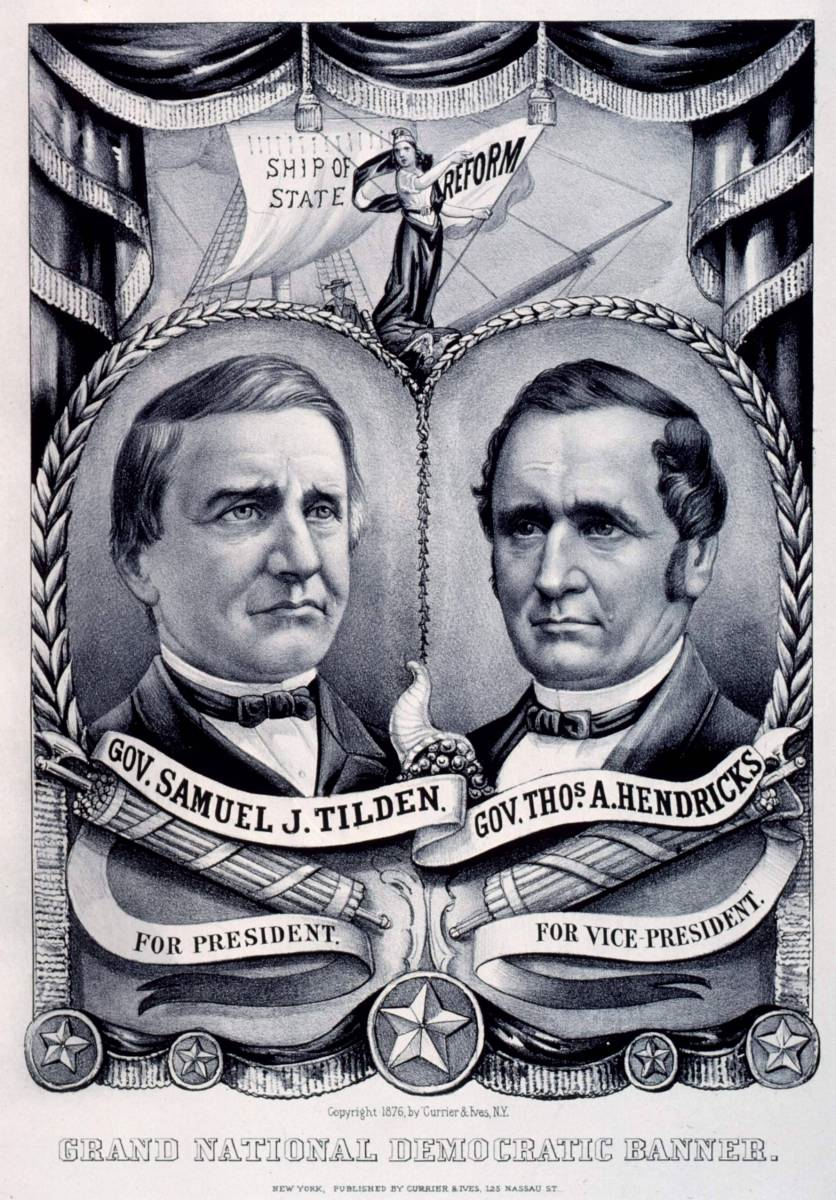

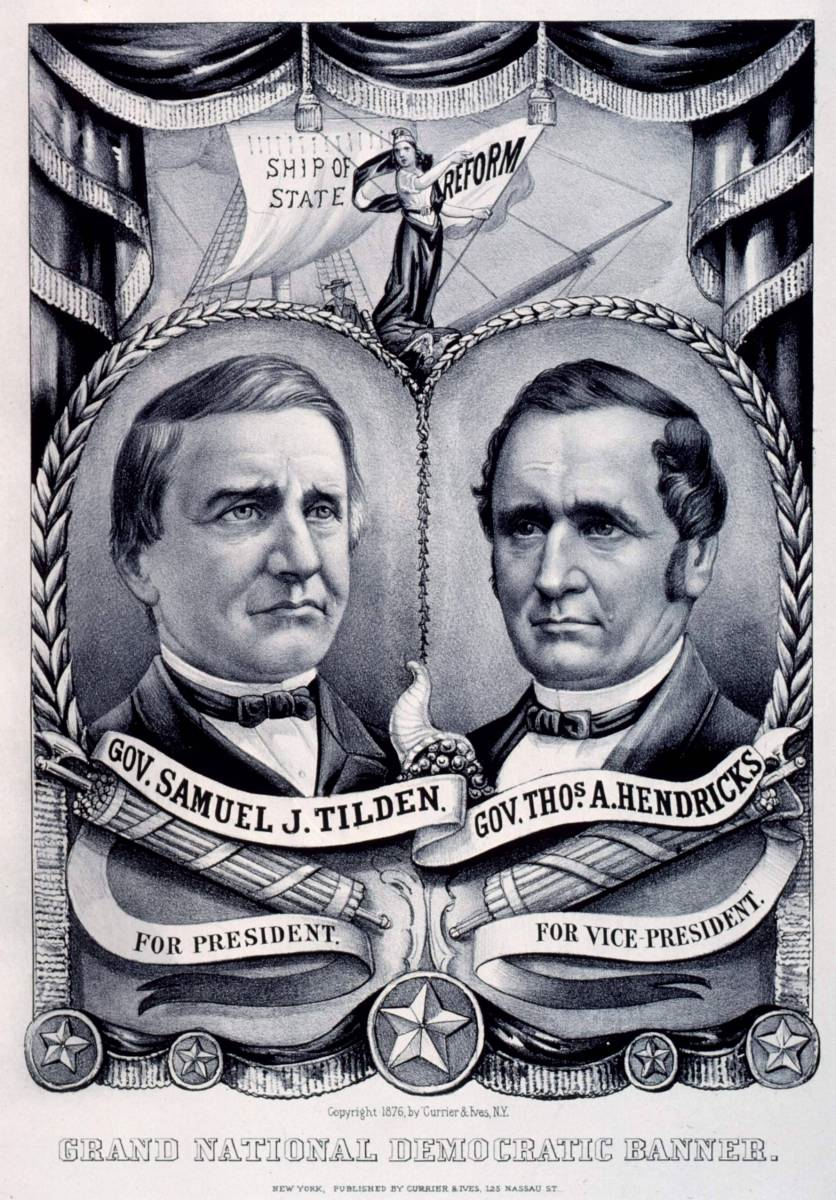

Democratic candidates:

* Samuel J. Tilden, governor of New York

* Thomas A. Hendricks, governor of

Democratic candidates:

* Samuel J. Tilden, governor of New York

* Thomas A. Hendricks, governor of

File:SamuelJonesTilden.jpg,

The Democratic Party's failure to nominate its own ticket in the previous presidential election, in which they had instead endorsed the Liberal Republican candidacy of

The Democratic Party's failure to nominate its own ticket in the previous presidential election, in which they had instead endorsed the Liberal Republican candidacy of

Official proceedings of the National Democratic convention, held in St. Louis, Mo., June 27th, 28th and 29th, 1876

'. (September 3, 2012). Source:

Official proceedings of the National Democratic convention, held in St. Louis, Mo., June 27th, 28th and 29th, 1876

'. (September 3, 2012). Source:

Official proceedings of the National Democratic convention, held in St. Louis, Mo., June 27th, 28th and 29th, 1876

' (September 3, 2012).

File:Peter Cooper Photograph.jpg,

The Greenback Party had been organized by agricultural interests in

Tilden, who had prosecuted machine politicians in New York and sent the political boss William M. Tweed to jail, ran as a reform candidate against the background of the corruption of the Grant administration. Both parties backed civil service reform. Both sides mounted mudslinging campaigns, with Democratic attacks on Republican corruption being countered by Republicans raising the Civil War issue, a tactic that was ridiculed by Democrats, who called it " waving the bloody shirt". Republicans chanted, "Not every Democrat was a rebel, but every rebel was a Democrat."

Hayes was a virtual unknown outside his home state of Ohio, where he had served two terms as a US Representative and then two terms as governor. Henry Adams called Hayes "a third-rate nonentity whose only recommendations are that he is obnoxious to no one". Hayes had served in the Civil War with distinction as colonel of the 23rd Ohio Regiment and was wounded several times, which made him marketable to veterans. He had later been brevetted as a major-general. His most important asset was his help to the Republican ticket in carrying Ohio, a crucial swing state. On the other side, the newspaperman John D. Defrees described Tilden as "a very nice, prim, little, withered-up, fidgety old bachelor, about one-hundred and twenty-pounds avoirdupois, who never had a genuine impulse for many nor any affection for woman".

The Democratic strategy for victory in the South relied on paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts and the White League. These groups saw themselves as the military wing of the Democrats. Using the strategy of the Mississippi Plan, they actively suppressed both black and white Republican voting. They violently disrupted meetings and rallies, attacked party organizers, and threatened potential voters with retaliation for voting Republican.

Because it was considered improper for a candidate to pursue the presidency actively, neither Tilden nor Hayes appeared publicly during the campaign. Speaking and leading rallies were left to their surrogates.

Tilden, who had prosecuted machine politicians in New York and sent the political boss William M. Tweed to jail, ran as a reform candidate against the background of the corruption of the Grant administration. Both parties backed civil service reform. Both sides mounted mudslinging campaigns, with Democratic attacks on Republican corruption being countered by Republicans raising the Civil War issue, a tactic that was ridiculed by Democrats, who called it " waving the bloody shirt". Republicans chanted, "Not every Democrat was a rebel, but every rebel was a Democrat."

Hayes was a virtual unknown outside his home state of Ohio, where he had served two terms as a US Representative and then two terms as governor. Henry Adams called Hayes "a third-rate nonentity whose only recommendations are that he is obnoxious to no one". Hayes had served in the Civil War with distinction as colonel of the 23rd Ohio Regiment and was wounded several times, which made him marketable to veterans. He had later been brevetted as a major-general. His most important asset was his help to the Republican ticket in carrying Ohio, a crucial swing state. On the other side, the newspaperman John D. Defrees described Tilden as "a very nice, prim, little, withered-up, fidgety old bachelor, about one-hundred and twenty-pounds avoirdupois, who never had a genuine impulse for many nor any affection for woman".

The Democratic strategy for victory in the South relied on paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts and the White League. These groups saw themselves as the military wing of the Democrats. Using the strategy of the Mississippi Plan, they actively suppressed both black and white Republican voting. They violently disrupted meetings and rallies, attacked party organizers, and threatened potential voters with retaliation for voting Republican.

Because it was considered improper for a candidate to pursue the presidency actively, neither Tilden nor Hayes appeared publicly during the campaign. Speaking and leading rallies were left to their surrogates.

HarpWeek As all of the remaining available Justices were Republicans, Republican Justice It was drawing perilously near to Inauguration Day, and thus the commission met on January 31. Each of the disputed state election cases (Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina) was respectively submitted to the commission by Congress. Eminent counsel appeared for each side, and there were double sets of returns from every one of the states named.

The commission first decided not to question any returns that were ''

It was drawing perilously near to Inauguration Day, and thus the commission met on January 31. Each of the disputed state election cases (Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina) was respectively submitted to the commission by Congress. Eminent counsel appeared for each side, and there were double sets of returns from every one of the states named.

The commission first decided not to question any returns that were ''

Image:1876 United States presidential election results map by county.svg, Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Image:PresidentialCounty1876Colorbrewer.gif, Map of presidential election results by county

Image:DemocraticPresidentialCounty1876Colorbrewer.gif, Map of Democratic presidential election results by county

Image:RepublicanPresidentialCounty1876Colorbrewer.gif, Map of Republican presidential election results by county

Image:OtherPresidentialCounty1876Colorbrewer.gif, Map of "other" presidential election results by county

Image:CartogramPresidentialCounty1876Colorbrewer.gif,

original 1895 edition

* Holt, Michael F. ''By One Vote: The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876'' (2008). 304 pages, * * Foley, Edward. 2016. ''Ballot Battles: The History of Disputed Elections in the United States''. Oxford University Press. * * * Huntzicker, William E. "Thomas Nast, Harper's Weekly, and the Election of 1876." in ''After The War'' (Routledge, 2017), pp. 53–68. * * * , popular account * Summers, Mark Wahlgren. ''The Press Gang: Newspapers and Politics, 1865–1878'' (1994) * Summers, Mark Wahlgren. ''The Era of Good Stealings'' (1993), covers corruption 1868–1877 * Richard White

"Corporations, Corruption, and the Modern Lobby: A Gilded Age Story of the West and the South in Washington, D.C."

''Southern Spaces'', April 16, 2009 *

online

* De Santis, Vincent P. "Rutherford B. Hayes and the Removal of the Troops and the End of Reconstruction", in ''Region, Race, and Reconstruction: Essays in Honor of C. Vann Woodward'', ed. by Morgan Kousser and James McPherson (Oxford University Press, 1982), 417–451. * Flynn, James Joseph. "The Disputed Election of 1876" (PhD dissertation, Fordham University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1953. 10992419). * Holt, Michael F. ''By one vote: the disputed presidential election of 1876'' (University Press of Kansas, 2008

online

* Palen, Marc-William. "Election of 1876/Compromise of 1877", in ''A Companion to the Reconstruction Presidents 1865–1881'' (2014): 415–430. * Peskin, Allan. "Was there a Compromise of 1877". ''Journal of American History'' 60.1 (1973): 63–75

online

** Woodward, C. Vann. "Yes, there was a Compromise of 1877". ''Journal of American History'' 60#2 (1973): 215–23. * Shofner, Jerrell H. "Fraud and Intimidation in the Florida Election of 1876". ''Florida Historical Quarterly'' 42.4 (1964): 321–330

online

* Simpson, Brooks D. "Ulysses S. Grant and the Electoral Crisis of 1876–77". ''Hayes Historical Journal'' 11 (1992): 5–17. * Sternstein, Jerome L. "The Sickles Memorandum: Another Look at the Hayes-Tilden Election-Night Conspiracy". ''Journal of Southern History'' (1966): 342–357

online

* Zuczek, Richard. "The last campaign of the Civil War: South Carolina and the revolution of 1876". ''Civil War History'' 42.1 (1996): 18–31

excerpt

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia ...for 1876''

(1885), comprehensive state-by-state coverage * * Chester, Edward W. ''A guide to political platforms'' (1977

online

* Porter, Kirk H., and Johnson, Donald Bruce, eds. ''National party platforms, 1840–1964'' (1965

online 1840–1956

Hayes Presidential Library

with essays by historians

from the Library of Congress

Rutherford B. Hayes On The Election of 1876: Original Letter

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

* ttp://www.countingthevotes.com/1876/ Election of 1876 in Counting the Votes {{Authority control

Presidential elections

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The ...

were held in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

on November 7, 1876. Republican Governor Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio very narrowly defeated Democratic Governor Samuel J. Tilden of New York. Following President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

's decision to retire after his second term, U.S. Representative James G. Blaine emerged as frontrunner for the Republican nomination; however, Blaine was unable to win a majority at the 1876 Republican National Convention, which settled on Hayes as a compromise candidate. The 1876 Democratic National Convention nominated Tilden on the second ballot.

The election was among the most contentious in American history, and was only resolved by the Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement, the Tilden-Hayes Compromise, the Bargain of 1877, or Corrupt bargain, the Corrupt Bargain, was a speculated unwritten political deal in the United States to settle the intense dispute ...

, in which Hayes agreed to end Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

in exchange for recognition of his presidency. In the first count, Tilden had 184 electoral votes (one vote short of a majority) to Hayes's 165, with the 20 votes from Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

, and Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

disputed. To address this constitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the constitution, political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variat ...

, Congress established the Electoral Commission

An election commission is a body charged with overseeing the implementation of electioneering process of any country. The formal names of election commissions vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and may be styled an electoral commission, a c ...

, which awarded all twenty votes and thus the presidency to Hayes in a strict party-line vote. Some Democratic representatives filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent a decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking ...

ed the commission's decision, hoping to prevent Hayes's inauguration; their filibuster was ultimately ended by party leader Samuel J. Randall. On March 2, 1877, the House and Senate confirmed Hayes as president. This was the last election taken under Reconstruction, in which some Southern states voted for a Republican candidate. Following the election Southern states were able to fully implement Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

laws, disenfranchising black Americans, beginning a period of Democrat domination known as the Solid South

The Solid South was the electoral voting bloc for the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party in the Southern United States between the end of the Reconstruction era in 1877 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the aftermath of the Co ...

. No Republican presidential nominee would win a former Confederate state until Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he was one of the most ...

in the 1920 United States presidential election

Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 2, 1920. The Republican ticket of senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio and governor Calvin Coolidge of Massachusetts defeated the Democratic ticket of governor James M. Cox of ...

.

It was the second of five U.S. presidential elections in which the winner did not win a plurality of the national popular vote, after the 1824 election. Although Tilden defeated Hayes in the official popular vote tally, the election involved substantial electoral fraud

Electoral fraud, sometimes referred to as election manipulation, voter fraud, or vote rigging, involves illegal interference with the process of an election, either by increasing the vote share of a favored candidate, depressing the vote share o ...

, voter intimidation by paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts, and disenfranchisement of black Republicans. The election had the highest voter turnout

In political science, voter turnout is the participation rate (often defined as those who cast a ballot) of a given election. This is typically either the percentage of Voter registration, registered voters, Suffrage, eligible voters, or all Voti ...

of the eligible voting-age population in American history, at 82.6%.Between 1828–1928: Tilden's 50.9% is the largest share of the popular vote received by a candidate who was not elected to the presidency, and this was the only presidential election in U.S. history in which the losing candidate won a majority of the popular vote. Tilden was also the last person to win an outright majority of the popular vote until William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

in 1896. As of 2024, this remains the only presidential election in which both candidates were sitting governors.

Nominations

Republican Party nomination

Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

File:JamesGBlaine.png, Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

James G. Blaine from Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

File:Benjamin Helm Bristow Brady - Handy U.S. Secretary of Treasury.jpg, Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Benjamin Bristow

File:Oliver Hazard Perry Morton - Brady-Handy.jpg, Senator Oliver P. Morton from Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

File:RConkling.jpg, Senator Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican Party (United States), Republican politician who represented New York (state), New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Se ...

from New York

File:JohnFHartranft.jpg, Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

John F. Hartranft of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

File:Marshall Jewell - Brady-Handy.jpg, Postmaster General Marshall Jewell

File:Elihu B. Washburne - Brady-Handy.jpg, Ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or so ...

Elihu B. Washburne from Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

File:VicePresident-WmAlWheeler.jpg, RepresentativeWilliam A. Wheeler from New York File:Honorable_Hamilton_Fish_Brady-Handy.jpg, Secretary of State

Hamilton Fish from New York

(declined to run) File:UlyssesGrant.jpg,

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

(declined in 1875)

It was widely assumed during the year 1875 that incumbent President

It was widely assumed during the year 1875 that incumbent President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

would run for a third term as president despite the poor economic conditions, the numerous political scandals that had developed since he assumed office in 1869, and despite a longstanding tradition set by George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

not to stay in office for more than two terms. Grant's inner circle advised him to go for a third term and he almost did so, but on December 15, 1875, the House, by a sweeping 233–18 vote, passed a resolution declaring that the two-term tradition was to prevent a dictatorship. Later that year, Grant ruled himself out of running in 1876. He instead tried to persuade Secretary of State Hamilton Fish to run for the presidency, but the 67-year-old Fish declined since he believed himself too old for that role. Grant nonetheless sent a letter to the convention imploring them to nominate Fish, but the letter was misplaced and never read to the convention. Fish later confirmed that he would have declined the presidential nomination even if it had been offered to him.

When the Sixth Republican National Convention assembled in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

, Ohio, on June 14, 1876, James G. Blaine appeared to be the presidential nominee. On the first ballot, Blaine was just 100 votes short of a majority. His vote began to slide after the second ballot, however, as many Republicans feared that Blaine could not win the general election. Anti-Blaine delegates could not agree on a candidate until his total rose to 41% on the sixth ballot. Leaders of the reform Republicans met privately and considered alternatives. They chose the reforming Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes, who had been gradually building support during the convention until he finished second on the sixth ballot. On the seventh ballot, Hayes was nominated for president with 384 votes, compared to 351 for Blaine and 21 for Benjamin Bristow. New York Representative William A. Wheeler was nominated for vice president by a much larger margin (366–89) over his chief rival, Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen, who later served as a member of the Electoral Commission, which awarded the election to Hayes.

Democratic Party nomination

Democratic candidates:

* Samuel J. Tilden, governor of New York

* Thomas A. Hendricks, governor of

Democratic candidates:

* Samuel J. Tilden, governor of New York

* Thomas A. Hendricks, governor of Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

* Winfield Scott Hancock, United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

major general from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

* William Allen, former governor of Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

* Thomas F. Bayard, U.S. senator from Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

* Joel Parker, former governor of New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

Samuel J. Tilden of New York

File:Thomas Andrews Hendricks.jpg, Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

File:WinfieldScottHancock2.jpg, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

File:William Allen governor Brady-Handy-crop.jpg, William Allen from Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

File:Thomas F. Bayard, Brady-Handy photo portrait, circa 1870-1880.jpg, Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

Thomas F. Bayard from Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

File:JoelParker-small.png, Joel Parker from New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

The Democratic Party's failure to nominate its own ticket in the previous presidential election, in which they had instead endorsed the Liberal Republican candidacy of

The Democratic Party's failure to nominate its own ticket in the previous presidential election, in which they had instead endorsed the Liberal Republican candidacy of Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congres ...

, had resulted in much debate about the party's viability. Any doubts about the party's future were dispelled firstly by the collapse of the Liberal Republicans in the aftermath of that election, and secondly by significant Democratic gains in the 1874 mid-term elections, which saw them take control of the House of Representatives for the first time in sixteen years.

The 12th Democratic National Convention assembled in St. Louis, Missouri, in June 1876, which was the first political convention ever held by one of the major American parties west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

. There were 5000 people jammed inside the auditorium in St. Louis amid hopes for the Democratic Party's first presidential victory in 20 years. The platform called for immediate and sweeping reforms in response to the scandals that had plagued the Grant administration. Tilden won more than 400 votes on the first ballot and the presidential nomination by a landslide on the second.

Tilden defeated Thomas A. Hendricks, Winfield Scott Hancock, William Allen, Thomas F. Bayard, and Joel Parker for the presidential nomination. Tilden overcame strong opposition from "Honest John" Kelly, the leader of New York's Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. It became the main local ...

, to obtain the presidential nomination. Thomas Hendricks was nominated for vice president since he was the only person to put forward for that position.

The Democratic platform pledged to replace the corruption of the Grant administration with honest, efficient government and to end "the rapacity of carpetbag tyrannies" in the South. It also called for treaty protection for naturalized United States citizens visiting their homelands, restrictions on Asian immigration, tariff reform, and opposition to land grants for railroads. It has been claimed that the voting Democrats received Tilden's presidential nomination with more enthusiasm than any leader since Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

.

Source: Official proceedings of the National Democratic convention, held in St. Louis, Mo., June 27th, 28th and 29th, 1876

'. (September 3, 2012). Source:

Official proceedings of the National Democratic convention, held in St. Louis, Mo., June 27th, 28th and 29th, 1876

'. (September 3, 2012). Source:

Official proceedings of the National Democratic convention, held in St. Louis, Mo., June 27th, 28th and 29th, 1876

' (September 3, 2012).

Greenback Party nomination

Greenback candidates: *Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper (February 12, 1791April 4, 1883) was an American industrialist, inventor, philanthropist, and politician. He designed and built the first American steam locomotive, the ''Tom Thumb (locomotive), Tom Thumb'', founded the Cooper Union ...

, U.S. philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

from New York

* Andrew Curtin, former governor of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

* William Allen, former governor of Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

* Alexander Campbell, U.S. representative from Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

Candidates gallery

Philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper (February 12, 1791April 4, 1883) was an American industrialist, inventor, philanthropist, and politician. He designed and built the first American steam locomotive, the ''Tom Thumb (locomotive), Tom Thumb'', founded the Cooper Union ...

from New York

File:Andrew Curtin2.jpg, Andrew Curtin from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

File:William Allen governor Brady-Handy-crop.jpg, William Allen from Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

File:AlexanderCampbell.png, Alexander Campbell from Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

, Indiana, in 1874 to urge the federal government to inflate the economy through the mass issuance of paper money called greenbacks. Its first national nominating convention was held in Indianapolis in the spring of 1876. Peter Cooper

Peter Cooper (February 12, 1791April 4, 1883) was an American industrialist, inventor, philanthropist, and politician. He designed and built the first American steam locomotive, the ''Tom Thumb (locomotive), Tom Thumb'', founded the Cooper Union ...

was nominated for president with 352 votes to 119 for three other contenders. The convention nominated Anti-Monopolist Senator Newton Booth of California for vice president. After Booth declined to run, the national committee chose Samuel Fenton Cary as his replacement on the ticket.

Prohibition Party nomination

TheProhibition Party

The Prohibition Party (PRO) is a Political parties in the United States, political party in the United States known for its historic opposition to the sale or consumption of alcoholic beverages and as an integral part of the temperance movemen ...

, in its second national convention in Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

, nominated Green Clay Smith as its presidential candidate and Gideon T. Stewart as its vice presidential candidate.

American National Party nomination

This small political party used several different names, often with different names in different states. It was a continuation of theAnti-Masonic Party

The Anti-Masonic Party was the earliest Third party (United States), third party in the United States. Formally a Single-issue politics, single-issue party, it strongly opposed Freemasonry in the United States. It was active from the late 1820s, ...

that met in 1872 and nominated Charles Francis Adams, Sr., for president. When Adams declined to run, the party did not contest the 1872 election.

The convention was held from June 8 to 10, 1875 in Liberty Hall, Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

, Pennsylvania. B.T. Roberts of New York served as chairman, and Jonathan Blanchard was the keynote speaker.

The platform supported the Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution, international arbitration, the reading of the scriptures in public schools, specie payments, justice for Native Americans, abolition of the Electoral College, and prohibition of the sale of alcoholic beverages. It declared the first day of the week to be a day of rest for the United States. The platform opposed secret societies and monopolies.

The convention considered three potential presidential candidates: Charles F. Adams, Jonathan Blanchard, and James B. Walker. When Blanchard declined to run, Walker was unanimously nominated for president. The convention then nominated Donald Kirkpatrick of New York unanimously for vice president.

General election

Campaign

Tilden, who had prosecuted machine politicians in New York and sent the political boss William M. Tweed to jail, ran as a reform candidate against the background of the corruption of the Grant administration. Both parties backed civil service reform. Both sides mounted mudslinging campaigns, with Democratic attacks on Republican corruption being countered by Republicans raising the Civil War issue, a tactic that was ridiculed by Democrats, who called it " waving the bloody shirt". Republicans chanted, "Not every Democrat was a rebel, but every rebel was a Democrat."

Hayes was a virtual unknown outside his home state of Ohio, where he had served two terms as a US Representative and then two terms as governor. Henry Adams called Hayes "a third-rate nonentity whose only recommendations are that he is obnoxious to no one". Hayes had served in the Civil War with distinction as colonel of the 23rd Ohio Regiment and was wounded several times, which made him marketable to veterans. He had later been brevetted as a major-general. His most important asset was his help to the Republican ticket in carrying Ohio, a crucial swing state. On the other side, the newspaperman John D. Defrees described Tilden as "a very nice, prim, little, withered-up, fidgety old bachelor, about one-hundred and twenty-pounds avoirdupois, who never had a genuine impulse for many nor any affection for woman".

The Democratic strategy for victory in the South relied on paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts and the White League. These groups saw themselves as the military wing of the Democrats. Using the strategy of the Mississippi Plan, they actively suppressed both black and white Republican voting. They violently disrupted meetings and rallies, attacked party organizers, and threatened potential voters with retaliation for voting Republican.

Because it was considered improper for a candidate to pursue the presidency actively, neither Tilden nor Hayes appeared publicly during the campaign. Speaking and leading rallies were left to their surrogates.

Tilden, who had prosecuted machine politicians in New York and sent the political boss William M. Tweed to jail, ran as a reform candidate against the background of the corruption of the Grant administration. Both parties backed civil service reform. Both sides mounted mudslinging campaigns, with Democratic attacks on Republican corruption being countered by Republicans raising the Civil War issue, a tactic that was ridiculed by Democrats, who called it " waving the bloody shirt". Republicans chanted, "Not every Democrat was a rebel, but every rebel was a Democrat."

Hayes was a virtual unknown outside his home state of Ohio, where he had served two terms as a US Representative and then two terms as governor. Henry Adams called Hayes "a third-rate nonentity whose only recommendations are that he is obnoxious to no one". Hayes had served in the Civil War with distinction as colonel of the 23rd Ohio Regiment and was wounded several times, which made him marketable to veterans. He had later been brevetted as a major-general. His most important asset was his help to the Republican ticket in carrying Ohio, a crucial swing state. On the other side, the newspaperman John D. Defrees described Tilden as "a very nice, prim, little, withered-up, fidgety old bachelor, about one-hundred and twenty-pounds avoirdupois, who never had a genuine impulse for many nor any affection for woman".

The Democratic strategy for victory in the South relied on paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts and the White League. These groups saw themselves as the military wing of the Democrats. Using the strategy of the Mississippi Plan, they actively suppressed both black and white Republican voting. They violently disrupted meetings and rallies, attacked party organizers, and threatened potential voters with retaliation for voting Republican.

Because it was considered improper for a candidate to pursue the presidency actively, neither Tilden nor Hayes appeared publicly during the campaign. Speaking and leading rallies were left to their surrogates.

Colorado

Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

was admitted to the Union as the 38th state on August 1, 1876; this was the first presidential election in which the state sent electors. There was insufficient time or money to organize a presidential election in the new state. Therefore, Colorado's state legislature selected the state's three members of the Electoral College. The Republican Party held a slim majority in the state legislature following a closely contested election on October 3, 1876. Many of the seats in that election had been decided by only a few hundred votes. On November 7, 1876, in a 50 to 24 vote, the state legislature chose Otto Mears, William Hadley, and Herman Beckurts to serve as the state's electors for president. All three of the state's electors cast their votes for Hayes. This was the last election in which any state chose electors through its state legislature, rather than by popular vote.

Electoral disputes and Compromise of 1877

Florida (with four electoral votes) and Louisiana (with eight) reported returns that favored Tilden, while Hayes led in South Carolina (with seven). However, the elections in each state were marked by electoral fraud and threats of violence against Republican voters. The most extreme case was in South Carolina, where an impossible 101 percent of all eligible voters in the state had their votes counted, and an estimated 150 Black Republicans were murdered. One of the points of contention revolved around the design of ballots. At the time, parties would print ballots or "tickets" to enable voters to support them in the open ballots. To aid illiterate voters, the parties would print symbols on the tickets, and in this election, many Democratic ballots were printed with the Republican symbol ofAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

on them. The Republican-dominated state electoral commissions subsequently rejected enough Democratic votes to award their electoral votes to Hayes.

In two Southern states, the governor recognized by the United States had signed the Republican certificates; the Democratic certificates from Florida were signed by the state attorney-general and the newly elected Democratic governor. Those from Louisiana were signed by the Democratic gubernatorial candidate and those from South Carolina by no state official. The Tilden electors in South Carolina claimed that they had been chosen by the popular vote although they were rejected by the state election board.

Meanwhile, in Oregon, the vote of a single elector was disputed. The statewide result clearly favored Hayes, but the state's Democratic governor, La Fayette Grover, claimed that one of the Republican electors, Ex-Postmaster John Watts, was ineligible under Article II, Section 1, of the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

since he had been a "person holding an office of trust or profit under the United States." Grover substituted a Democratic elector in Watts's place.

The two Republican electors dismissed Grover's action and reported three votes for Hayes. However, the Democratic elector, C. A. Cronin, reported one vote for Tilden and two votes for Hayes. The two Republican electors presented a certificate signed by the secretary of state of Oregon, and Cronin and the two electors whom he appointed (Cronin voted for Tilden while his associates voted for Hayes) presented a certificate signed by the governor and attested by the secretary of state.

Ultimately, all three of Oregon's votes were awarded to Hayes, who had a majority of one in the Electoral College. The Democrats claimed fraud, and suppressed excitement pervaded the country. Threats were even muttered that Hayes would never be inaugurated. In Columbus, Ohio

Columbus (, ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities in Ohio, most populous city of the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 United States census, 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the List of United States ...

, a shot was fired at Hayes's residence as he sat down to dinner. After supporters marched to his home to call for the President, Hayes urged the crowd that "it is impossible, at so early a time, to obtain the result".Morris, Roy, Jr. (2003). ''Fraud of the Century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden and the Stolen Election of 1876''. New York: Simon and Schuster, pp. 168, 239. Grant quietly strengthened the military force in and around Washington.

The Constitution provides that "the President of the Senate shall, in presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the lectoralcertificates, and the votes shall then be counted." The Republicans held that the power to count the votes lay with the President of the Senate, with the House and Senate being mere spectators. The Democrats objected to that construction, since the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, the Republican Thomas W. Ferry, could then count the votes of the disputed states for Hayes.

The Democrats insisted that Congress should continue the practice followed since 1865: no vote objected to should be counted except by the concurrence of both houses. Since the House had a solid Democratic majority, rejecting the vote of one state, therefore, would elect Tilden.

Facing an unprecedented constitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the constitution, political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variat ...

, the Congress passed a law on January 29, 1877, to form a 15-member Electoral Commission

An election commission is a body charged with overseeing the implementation of electioneering process of any country. The formal names of election commissions vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and may be styled an electoral commission, a c ...

, which would settle the result. Five members were selected from each house of Congress, and they were joined by five members of the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

, with William M. Evarts serving as counsel for the Republican Party.

The majority party in each house named three members and the minority party two members. As the Republicans controlled the Senate and the Democrats controlled the House of Representatives, that yielded five Democratic and five Republican members of the commission. Of the Supreme Court justices, two Republicans and two Democrats were chosen, with the fifth to be selected by those four.

The justices first selected the independent Justice David Davis. According to one historian, "No one, perhaps not even Davis himself, knew which presidential candidate he preferred." Just as the Electoral Commission Bill was passing Congress, the Illinois Legislature elected Davis to the Senate, and Democrats in the legislature believed that they had purchased Davis's support by voting for him. However, they had miscalculated, as Davis promptly excused himself from the commission and resigned as a Justice to take his Senate seat."Hayes v. Tilden: The Electoral College Controversy of 1876–1877."HarpWeek As all of the remaining available Justices were Republicans, Republican Justice

Joseph P. Bradley

Joseph Philo Bradley (March 14, 1813 – January 22, 1892) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1870 to 1892. He ...

, who was considered the most impartial remaining member of the court was selected. That selection proved decisive.

It was drawing perilously near to Inauguration Day, and thus the commission met on January 31. Each of the disputed state election cases (Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina) was respectively submitted to the commission by Congress. Eminent counsel appeared for each side, and there were double sets of returns from every one of the states named.

The commission first decided not to question any returns that were ''

It was drawing perilously near to Inauguration Day, and thus the commission met on January 31. Each of the disputed state election cases (Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina) was respectively submitted to the commission by Congress. Eminent counsel appeared for each side, and there were double sets of returns from every one of the states named.

The commission first decided not to question any returns that were ''prima facie

''Prima facie'' (; ) is a Latin expression meaning "at first sight", or "based on first impression". The literal translation would be "at first face" or "at first appearance", from the feminine forms of ' ("first") and ' ("face"), both in the a ...

'' lawful. Bradley then joined the other seven Republican committee members in a series of 8–7 votes that gave all 20 disputed electoral votes to Hayes, which gave Hayes a 185–184 electoral vote victory. The commission adjourned on March 2. Hayes privately took the oath of office the next day and was publicly sworn into office on March 5, 1877, and Hayes was inaugurated without disturbance.

The Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement, the Tilden-Hayes Compromise, the Bargain of 1877, or Corrupt bargain, the Corrupt Bargain, was a speculated unwritten political deal in the United States to settle the intense dispute ...

might be a reason for the Democrats accepting the Electoral Commission. During intense closed-door meetings, Democratic leaders agreed reluctantly to accept Hayes as president in return for the withdrawal of federal troops from the last two Southern states that were still occupied: South Carolina and Louisiana. Republican leaders in return agreed on a number of handouts and entitlements, including federal subsidies for a transcontinental railroad line through the South. Although some of the promises were not kept, particularly the railroad proposal, that was enough for the time being to avert a dangerous standoff.

The returns accepted by the Commission put Hayes's margin of victory in South Carolina at 889 votes, the second-closest popular vote margin in a decisive state in U.S. history, after the election of 2000, which was decided by 537 votes in Florida. In 2000, the margin of victory in the Electoral College for George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

was five votes, as opposed to Hayes' one vote.

Upon his defeat, Tilden said, "I can retire to public life with the consciousness that I shall receive from posterity the credit of having been elected to the highest position in the gift of the people, without any of the cares and responsibilities of the office."

Congress would eventually enact the Electoral Count Act

The Electoral Count Act of 1887 (ECA) (, later codified at Title 3 of the United States Code, Title 3, Chapter 1) is a United States federal law that added to procedures set out in the Constitution of the United States for the counting of Uni ...

in 1887 to provide more detailed rules for the counting of electoral votes, especially in cases of multiple slates of electors being received from a single state.

Results

37.1% of the voting age population and 82.6% of eligible voters participated in the election. According to the commission's rulings, of the 2,249 counties and independent cities making returns, Tilden won in 1,301 (57.9%), and Hayes carried only 947 (42.1%). One county (<0.1%) inNevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It borders Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the seventh-most extensive, th ...

split evenly between Tilden and Hayes.

The Greenback ticket did not have a major impact on the election's outcome by attracting slightly under one percent of the popular vote; nonetheless, Cooper had the strongest performance of any third-party presidential candidate since John Bell in 1860

Events

January

* January 2 – The astronomer Urbain Le Verrier announces the discovery of a hypothetical planet Vulcan (hypothetical planet), Vulcan at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences in Paris, France.

* January 10 &ndas ...

. The Greenbacks' best showings were in Kansas, where Cooper earned just over six percent of the vote, and in Indiana, where he earned 17,207 votes, which far exceeded Tilden's margin of victory of roughly 5,500 votes over Hayes in that state.

The election of 1876 was the last one held before the end of the Reconstruction era, which sought to protect the rights of African Americans in the South, who usually voted for Republican presidential candidates. No antebellum slave state would be carried by a Republican again until the 1896 realignment, which saw William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

carry Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia, and Kentucky. This is the closest electoral college result in American history, and the second-closest victory in the tipping point state with South Carolina being decided by 889 votes (only the 2000 election in Florida was closer).

No Republican presidential candidate until Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he was one of the most ...

in 1920

Events January

* January 1

** Polish–Soviet War: The Russian Red Army increases its troops along the Polish border from 4 divisions to 20.

** Kauniainen in Finland, completely surrounded by the city of Espoo, secedes from Espoo as its ow ...

would carry any states that seceded and joined the Confederacy. That year, he carried Tennessee, which had never experienced a long period of occupation by federal troops and had been completely "reconstructed" well before the first presidential election of the Reconstruction period ( 1868). None of the Southern states that experienced long periods of occupation by federal troops was carried by a Republican again until Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

in 1928

Events January

* January – British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith reports the results of Griffith's experiment, indirectly demonstrating that DNA is the genetic material.

* January 1 – Eastern Bloc emigration and defection: Boris B ...

, when he won Florida, North Carolina, Texas and Virginia. 1876 proved to be the last election until 1956

Events

January

* January 1 – The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Anglo-Egyptian Condominium ends in Sudan after 57 years.

* January 8 – Operation Auca: Five U.S. evangelical Christian Missionary, missionaries, Nate Saint, Roger Youderian, E ...

in which the Republican nominee carried Louisiana, as well as the last in which the Republican won South Carolina until 1964

Events January

* January 1 – The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland is dissolved.

* January 5 – In the first meeting between leaders of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches since the fifteenth century, Pope Paul VI and Patria ...

. Both states would not defect from the Democratic ticket again until 1948

Events January

* January 1

** The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is inaugurated.

** The current Constitutions of Constitution of Italy, Italy and of Constitution of New Jersey, New Jersey (both later subject to amendment) ...

, when they backed the " Dixiecrat" candidate Strom Thurmond.

18.33% of Hayes' votes came from the eleven states of the former Confederacy, with him taking 40.40% of the vote in that region. Although 1876 marked the last competitive two-party election in the South before the Democratic dominance of the South until 1948 and of the Border States until 1896, it was also the last presidential election (as of 2020) in which the Democrats won the wartime Unionist Mitchell County, North Carolina; Wayne County, Tennessee; Henderson County, Tennessee; and Lewis County, Kentucky

Lewis County is near the northeastern tip of the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 13,080. Its county seat is Vanceburg, Kentucky, Vanceburg.

History

Kentucky was part of Virginia unti ...

. Hayes was also the only Republican president ever to be elected who failed to carry Indiana, and the first to win without Connecticut.

Geography of results

Cartographic gallery

Cartogram

A cartogram (also called a value-area map or an anamorphic map, the latter common among German-speakers) is a thematic map of a set of features (countries, provinces, etc.), in which their geographic size is altered to be Proportionality (math ...

of presidential election results by county

Image:CartogramDemocraticPresidentialCounty1876Colorbrewer.gif, Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

Image:CartogramRepublicanPresidentialCounty1876Colorbrewer.gif, Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county

Image:CartogramOtherPresidentialCounty1876Colorbrewer.gif, Cartogram of "other" presidential election results by county

Results by state

Source: Data fromWalter Dean Burnham

Walter Dean Burnham (June 15, 1930 – October 4, 2022) was an American political scientist who was an expert on elections and voting patterns. He was known for his quantitative analysis of national trends and patterns in voting behavior, t ...

, ''Presidential ballots, 1836–1892'' (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955) pp 247–57.

States that flipped from Republican to Democratic

*Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

*Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

*Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

*Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

*Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

*Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

*New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

* New York

*North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

*Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

*West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

Close states

Margin of victory less than 1% (7 electoral votes): # ''South Carolina, 0.5% (889 votes) (tipping point state)'' Margin of victory less between 1% and 5% (164 electoral votes): #Ohio, 1.1% (7,516 votes) #Indiana, 1.3% (5,515 votes) #California, 1.8% (2,798 votes) #Florida, 2.0% (922 votes) #Pennsylvania, 2.4% (17,980 votes) #Connecticut, 2.4% (2,894 votes) #Wisconsin, 2.4% (6,141 votes) #New York, 3.2% (32,742 votes) #Louisiana, 3.3% (4,807 votes) #Oregon, 3.5% (1,057 votes) #Illinois, 3.5% (19,621 votes) #New Hampshire, 3.8% (3,030 votes) Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (33 electoral votes): #Nevada, 5.5% (1,075 votes) #New Jersey, 5.7% (12,445 votes) #North Carolina, 7.2% (16,943 votes) #Michigan, 7.9% (25,216 votes)Cultural references

*The presidential election of 1876 is a major theme ofGore Vidal

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal ( ; born Eugene Louis Vidal, October 3, 1925 – July 31, 2012) was an American writer and public intellectual known for his acerbic epigrammatic wit. His novels and essays interrogated the Social norm, social and sexual ...

's novel ''1876

Events

January

* January 1

** The Reichsbank opens in Berlin.

** The Bass Brewery Red Triangle becomes the world's first registered trademark symbol.

*January 27 – The Northampton Bank robbery occurs in Massachusetts.

February

* Febr ...

''.

See also

* American election campaigns in the 19th century *History of the United States (1865–1918)

The history of the present-day United States began in roughly 15,000 BC with the arrival of Peopling of the Americas, the first people in the Americas. In the late 15th century, European colonization of the Americas, European colonization beg ...

* Inauguration of Rutherford B. Hayes

* 1876–77 United States House of Representatives elections

* 1876–77 United States Senate elections

* Disputed government of South Carolina of 1876–77

* Third Party System

* Contested elections in American history

References

Works cited

* *Sources

* John Bigelow, Author, Edited by, Nikki Oldaker, ''The Life of Samuel J. Tilden'' (2009 Revised edition-retype-set-new photos). 444 pages,original 1895 edition

* Holt, Michael F. ''By One Vote: The Disputed Presidential Election of 1876'' (2008). 304 pages, * * Foley, Edward. 2016. ''Ballot Battles: The History of Disputed Elections in the United States''. Oxford University Press. * * * Huntzicker, William E. "Thomas Nast, Harper's Weekly, and the Election of 1876." in ''After The War'' (Routledge, 2017), pp. 53–68. * * * , popular account * Summers, Mark Wahlgren. ''The Press Gang: Newspapers and Politics, 1865–1878'' (1994) * Summers, Mark Wahlgren. ''The Era of Good Stealings'' (1993), covers corruption 1868–1877 * Richard White

"Corporations, Corruption, and the Modern Lobby: A Gilded Age Story of the West and the South in Washington, D.C."

''Southern Spaces'', April 16, 2009 *

Further reading

* Calhoun, Charles W. ''Conceiving a New Republic: The Republican Party and the Southern Question, 1869–1900'' (University Press of Kansas, 2006) * Clendenen, Clarence C. "President Hayes'" Withdrawal" of the Troops: An Enduring Myth". ''South Carolina Historical Magazine'' 70.4 (1969): 240–250online

* De Santis, Vincent P. "Rutherford B. Hayes and the Removal of the Troops and the End of Reconstruction", in ''Region, Race, and Reconstruction: Essays in Honor of C. Vann Woodward'', ed. by Morgan Kousser and James McPherson (Oxford University Press, 1982), 417–451. * Flynn, James Joseph. "The Disputed Election of 1876" (PhD dissertation, Fordham University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1953. 10992419). * Holt, Michael F. ''By one vote: the disputed presidential election of 1876'' (University Press of Kansas, 2008

online

* Palen, Marc-William. "Election of 1876/Compromise of 1877", in ''A Companion to the Reconstruction Presidents 1865–1881'' (2014): 415–430. * Peskin, Allan. "Was there a Compromise of 1877". ''Journal of American History'' 60.1 (1973): 63–75

online

** Woodward, C. Vann. "Yes, there was a Compromise of 1877". ''Journal of American History'' 60#2 (1973): 215–23. * Shofner, Jerrell H. "Fraud and Intimidation in the Florida Election of 1876". ''Florida Historical Quarterly'' 42.4 (1964): 321–330

online

* Simpson, Brooks D. "Ulysses S. Grant and the Electoral Crisis of 1876–77". ''Hayes Historical Journal'' 11 (1992): 5–17. * Sternstein, Jerome L. "The Sickles Memorandum: Another Look at the Hayes-Tilden Election-Night Conspiracy". ''Journal of Southern History'' (1966): 342–357

online

* Zuczek, Richard. "The last campaign of the Civil War: South Carolina and the revolution of 1876". ''Civil War History'' 42.1 (1996): 18–31

excerpt

Primary sources

''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia ...for 1876''

(1885), comprehensive state-by-state coverage * * Chester, Edward W. ''A guide to political platforms'' (1977

online

* Porter, Kirk H., and Johnson, Donald Bruce, eds. ''National party platforms, 1840–1964'' (1965

online 1840–1956

External links

*Hayes Presidential Library

with essays by historians

from the Library of Congress

Rutherford B. Hayes On The Election of 1876: Original Letter

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

* ttp://www.countingthevotes.com/1876/ Election of 1876 in Counting the Votes {{Authority control

1876 United States presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 7, 1876. Republican Party (United States), Republican Governor Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio very narrowly defeated Democratic Party (United Sta ...

Reconstruction Era

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

Presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

United States election controversies

Electoral fraud in the United States

William A. Wheeler

Thomas A. Hendricks