1837 Upper Canada Rebellion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Upper Canada Rebellion was an insurrection against the

Sir

Sir

On July 10, 1832, US President Andrew Jackson vetoed the bill for the refinancing of the

On July 10, 1832, US President Andrew Jackson vetoed the bill for the refinancing of the

The rebels from Toronto travelled to the United States in groups of two. Mackenzie, Duncombe, Rolph and 200 supporters fled to

The rebels from Toronto travelled to the United States in groups of two. Mackenzie, Duncombe, Rolph and 200 supporters fled to

The British government was concerned about the rebellion, especially in light of the strong popular support for the rebels in the United States and the

The British government was concerned about the rebellion, especially in light of the strong popular support for the rebels in the United States and the

/ref> so that Arthur reported to Durham. Durham was assigned to report on the grievances among the British North American colonists and find a way to appease them. His report eventually led to greater autonomy in the Canadian colonies and the union of Upper and Lower Canada into the

William Lyon Mackenzie

Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, Biographi.ca * "Rebellion in Upper Canada, 1837" by J. Edgar Re

"MHS Transactions: Rebellion in Upper Canada, 1837"

Mhs.mb.ca * Brown, Richard. ''Rebellion in Canada, 1837–1885: Autocracy, Rebellion and Liberty'' (Vol. 1) (2012)

excerpt volume 1

''Rebellion in Canada, 1837–1885, Volume 2: The Irish, the Fenians and the Metis'' (2012

excerpt for vol. 2

* Ducharme, Michel

"Closing the Last Chapter of the Atlantic Revolution: The 1837–38 Rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada,"

''Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society'' 116(2): 413–430; (2006) * Dunning, Tom. "The Canadian Rebellions of 1837 and 1838 as a Borderland War: A Retrospective," ''Ontario History'' (2009) 101#2 pp 129–141. * Mann, Michael. ''A Particular Duty: The Canadian Rebellions, 1837–1839'' (1986) * Read, Colin. ''The rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada'' (The Canadian Historical Association historical booklet) (1988), short pamphlet * Tiffany, Orrin Edward. ''The Relations of the United States to the Canadian Rebellion of 1837–1838'' (2010)

"The story of the Upper Canadian rebellion

. C. Blackett Robinson, Toronto * Charles Lindsey, ''The Life and Times of William Lyon Mackenzie and the Rebellion of 1837–38.'' 1862; cited by Betsy Dewar Boyce, ''The Rebels of Hastings'', 1992.

Proceedings of the Legislative Council of Upper Canada on the bill sent up from the House of Assembly, entitled, An act to amend the jury laws of this province

(February 25, 1836) * Colin Read and Ronald J. Stagg, eds.

The Rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada: A collection of documents

' (The Publications of the Champlain Society, Ontario Series XII, 1985), 471pp (with free online access). * Greenwood,F. Murray, and Barry Wright (2 vol 1996, 2002

Canadian state trials – Rebellion and invasion in the Canadas, 1837–1839

Society for Canadian Legal History by University of Toronto Press,

by William Lyon Mackenzie, 1839 from th

Ontario Time Machine

Samuel Lount Film

an

Samuel Lount's History

The feature film is about the injustice of the system under the Family Compact's rule. * . by Serge Gorelsky

"Upper canada rebellion

. www.canadianencyclopedia.ca {{British colonial campaigns Political history of Canada December 1837 Political violence in Canada

oligarchic

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or throug ...

government of the British colony of Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada () was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the Province of Queb ...

(present-day Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

) in December 1837. While public grievances had existed for years, it was the rebellion

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

in Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada () was a British colonization of the Americas, British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence established in 1791 and abolished in 1841. It covered the southern portion o ...

(present-day Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

), which started the previous month, that emboldened rebels in Upper Canada to revolt.

The Upper Canada Rebellion was largely defeated shortly after it began, although resistance lingered until 1838. While it shrank, it became more violent, mainly through the support of the Hunters' Lodges, a secret United States–based militia that emerged around the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

, and launched the Patriot War

The Patriot War was a conflict along the Canada–United States border in which bands of raiders attacked the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British colony of Upper Canada more than a dozen times between December 1837 and Decemb ...

in 1838.

Some historians suggest that although they were not directly successful or large, the rebellions in 1837 should be viewed in the wider context of the late-18th- and early-19th-century Atlantic Revolutions

The Age of Revolution is a period from the late-18th to the mid-19th centuries during which a number of significant revolutionary movements occurred in most of Europe and the Americas. The period is noted for the change from Absolutism (Europea ...

including the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

in 1776, the French Revolution of 1789–99, the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution ( or ; ) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolution was the only known Slave rebellion, slave up ...

of 1791–1804, the Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 (; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ''The Turn out'', ''The Hurries'', 1798 Rebellion) was a popular insurrection against the British Crown in what was then the separate, but subordinate, Kingdom of Ireland. The m ...

, and the independence struggles of Spanish America (1810–1825). While these rebellions differed in that they also struggled for republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

, they were inspired by similar social problems stemming from poorly regulated oligarchies, and sought the same democratic ideals, which were also shared by the United Kingdom's Chartists

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of ...

.

The rebellion in Lower Canada, followed by its Upper Canada counterpart, led directly to Lord Durham's Report on the Affairs of British North America

The ''Report on the Affairs of British North America'', (, 1839) commonly known as the ''Durham Report'' or ''Lord Durham's Report'', is an important document in the history of Quebec, Ontario, Canada and the British Empire.

The notable Briti ...

, and to The British North America Act, 1840, which partially reformed the British provinces into a unitary system, leading to the formation of Canada as a nation in 1867.

Background

Political structure of Upper Canada

Many of the grievances which underlay the Rebellion involved the provisions of the Constitutional Act of 1791, which had created Upper Canada's political framework. TheFamily Compact

The Family Compact was a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in Upper Canada (today's Ontario) from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was the Upper Canadian equivalent of the Château Clique in L ...

dominated the government of Upper Canada and the financial and religious institutions associated with it. They were the leading members of the administration: executive councillors, legislative councillors, senior officials and some members of the judiciary. Their administrative roles were intimately tied to their business activities. For example, William Allan "was an executive councillor, a legislative councillor, President of the Toronto and Lake Huron Railroad, Governor of the British American Fire and Life Assurance Company and President of the Board of Trade." Members of the Family Compact utilized their official positions for monetary gain, especially through corporations such as the Bank of Upper Canada

The Bank of Upper Canada was established in 1821 under a charter granted by the legislature of Upper Canada in 1819 to a group of Kingston merchants. The charter was appropriated by the more influential Executive Councillors to the Lt. Governor, t ...

, and the two land companies (the Clergy Corporation and the Canada Company

The Canada Company was a private British land development company that was established to aid in the colonization of a large part of Upper Canada. It was incorporated by royal charter on August 19, 1826, under the ( 6 Geo. 4. c. 75) of the B ...

) that between them controlled two-sevenths of the land in the province. Lacking the minimum capital needed to found the bank, the corporate leaders persuaded the government to subscribe for a quarter of its shares. During the 1830s, a third of the bank's board were Legislative or Executive Councillors, and the remainder all magistrates. Despite repeated attempts, the elected Legislature – which had chartered the bank – could not obtain details on the bank's workings. Politician and former journalist William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie (March12, 1795 August28, 1861) was a Scottish-born Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the Family Compact, a term used to identify the establishment of Upper Canada. He represe ...

saw the bank as a prop of the Government and demanded farmers withdraw the money they had deposited in the bank and public confidence in the bank decreased.

Demographic changes

The government of Upper Canada feared a growing interest in American-inspiredrepublicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

in the province because of the increase in immigration of American settlers to the province. The large number of migrants led American legislators to speculate that bringing Upper Canada into the American fold would be a "mere matter of marching". After the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

the colonial government prevented Americans from swearing allegiance, thereby making them ineligible to obtain land grants. Relations between the appointed Legislative Council

A legislative council is the legislature, or one of the legislative chambers, of a nation, colony, or subnational division such as a province or state. It was commonly used to label unicameral or upper house legislative bodies in the Brit ...

and the elected Legislative Assembly became increasingly strained in the years after the war, over issues of immigration, taxation, banking and land speculation.

Political unions

The Upper Canada Central Political Union was organized in 1832–33 by Thomas David Morrison and collected 19,930 signatures on a petition protesting William Lyon Mackenzie's expulsion from the House of Assembly. TheReformers

A reformer is someone who works for reform.

Reformer may also refer to:

* Catalytic reformer, in an oil refinery

*Methane reformer, producing hydrogen

* Steam reformer

* Hydrogen reformer, extracting hydrogen

*Methanol reformer, producing hydrogen ...

won a majority in the elections held in 1834 for the Legislative Assembly of the 12th Parliament of Upper Canada but the Family Compact held the majority in the Legislative Council. The union was reorganized as the Canadian Alliance Society in 1835 and adopted much of the platform of the Owenite

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperativ ...

National Union of the Working Classes in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, England, that were to be integrated into the Chartist movement in England. In pursuit of this democratic goal, the Chartists eventually staged a similar armed rebellion, the Newport Rising

The Newport Rising was the last large-scale armed rising in Wales, by Chartism, Chartists whose demands included democracy and the right to vote with a secret ballot.

On Monday 4 November 1839, approximately 4,000 Chartist sympathisers, under ...

, in Wales in 1839. The Canadian Alliance Society was reborn as the Constitutional Reform Society in 1836, and led by the more moderate reformer, William W. Baldwin. The Society took its final form as the Toronto Political Union in 1837 and they organized local "Vigilance Committees" to elect delegates to a Constitutional Convention in July 1837. This became the organizational structure for the Rebellion and most of the rebel organizers were elected Constitutional Convention delegates.

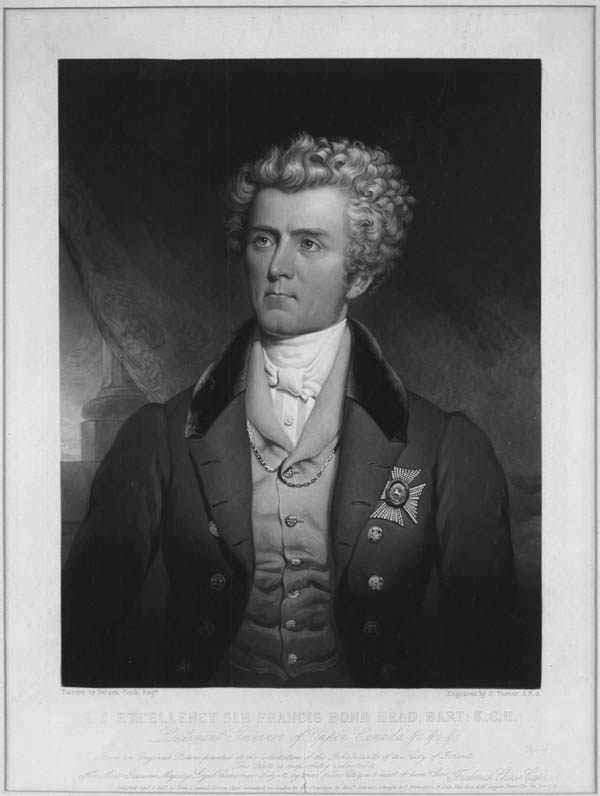

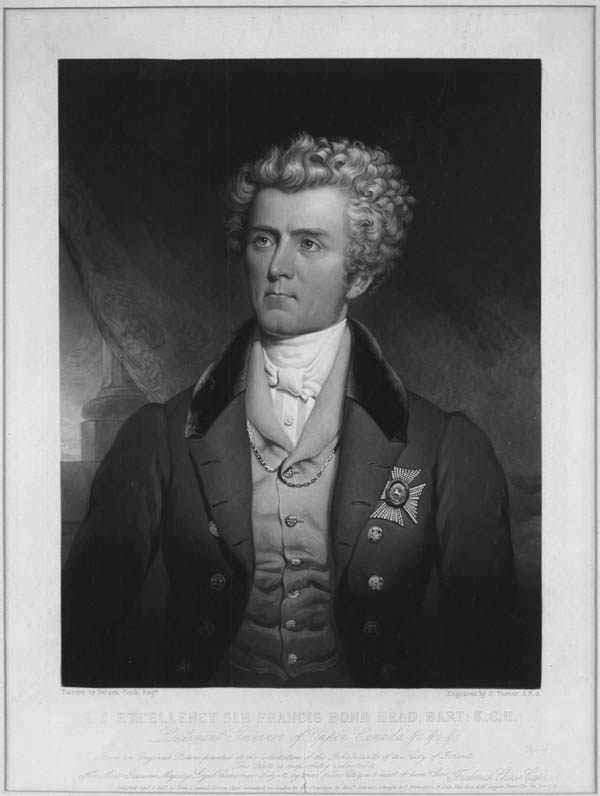

Francis Bond Head and the elections of 1836

Sir

Sir Francis Bond Head

Sir Francis Bond Head, 1st Baronet KCH PC (7 December 1793 – 20 July 1875) was Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada during the rebellion of 1837.

Biography

Head was an officer in the corps of Royal Engineers of the British Army from 181 ...

was appointed as Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a " second-in-com ...

and the Reform movement believed he would support their ideas. After meeting with Reformers, Bond Head concluded that they were disloyal to the British Empire and allied himself with the Family Compact. He refused proposals to bring responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

to Upper Canada, responding in a sarcastic tone that belittled reformers. The Reform-dominated Assembly responded by refusing to pass the money bill

In the Westminster system (and, colloquially, in the United States), a money bill or supply bill is a bill that solely concerns taxation or government spending (also known as appropriation of money), as opposed to changes in public law.

Con ...

, which halted the payment of salaries and pensions to many government workers. Bond Head then refused to pass any legislation from that government session including major public works projects. This caused a recession in Upper Canada. The movement was disappointed when Bond Head made it clear he had no intention of consulting the Executive Council in the daily operations of the administration. The Executive Council resigned, provoking widespread discontent and an election in 1834.

Unlike previous Lt. Governors, Bond Head actively supported Tory candidates and utilized Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants. It also has lodges in England, Grand Orange Lodge of ...

violence in order to ensure their election. He appealed to the people's desire to remain part of the British Empire and a paternalistic attitude of the Crown providing goods for the people. Reformers such as Mackenzie and Samuel Lount

Samuel Lount (September 24, 1791 – April 12, 1838) was a blacksmith, farmer, magistrate and member of the Legislative Assembly in the province of Upper Canada for Simcoe County from 1834 to 1836. He was an organizer of the failed Upper Ca ...

lost their seats in the Legislature and they alleged that the election was fraudulent. They prepared a petition to the Crown protesting the abuses, carried to London by Charles Duncombe Charles Duncombe may refer to:

* Charles Duncombe (English banker) (1648–1711), English banker, MP and Lord Mayor

* Charles Duncombe, 1st Baron Feversham (1764–1841), English MP

*Charles Duncombe (Upper Canada Rebellion) (1792–1867), American ...

, but the Colonial Office refused to hear him. The new Tory-dominated Legislature passed laws that exacerbated tensions including continuing the Legislative session after the death of the King, prohibiting members of the Legislature from serving as Executive Councillors, making it easier to sue indebted farmers, protecting the Bank of Upper Canada from bankruptcy, and giving Legislative Councillors charters for their own banks.

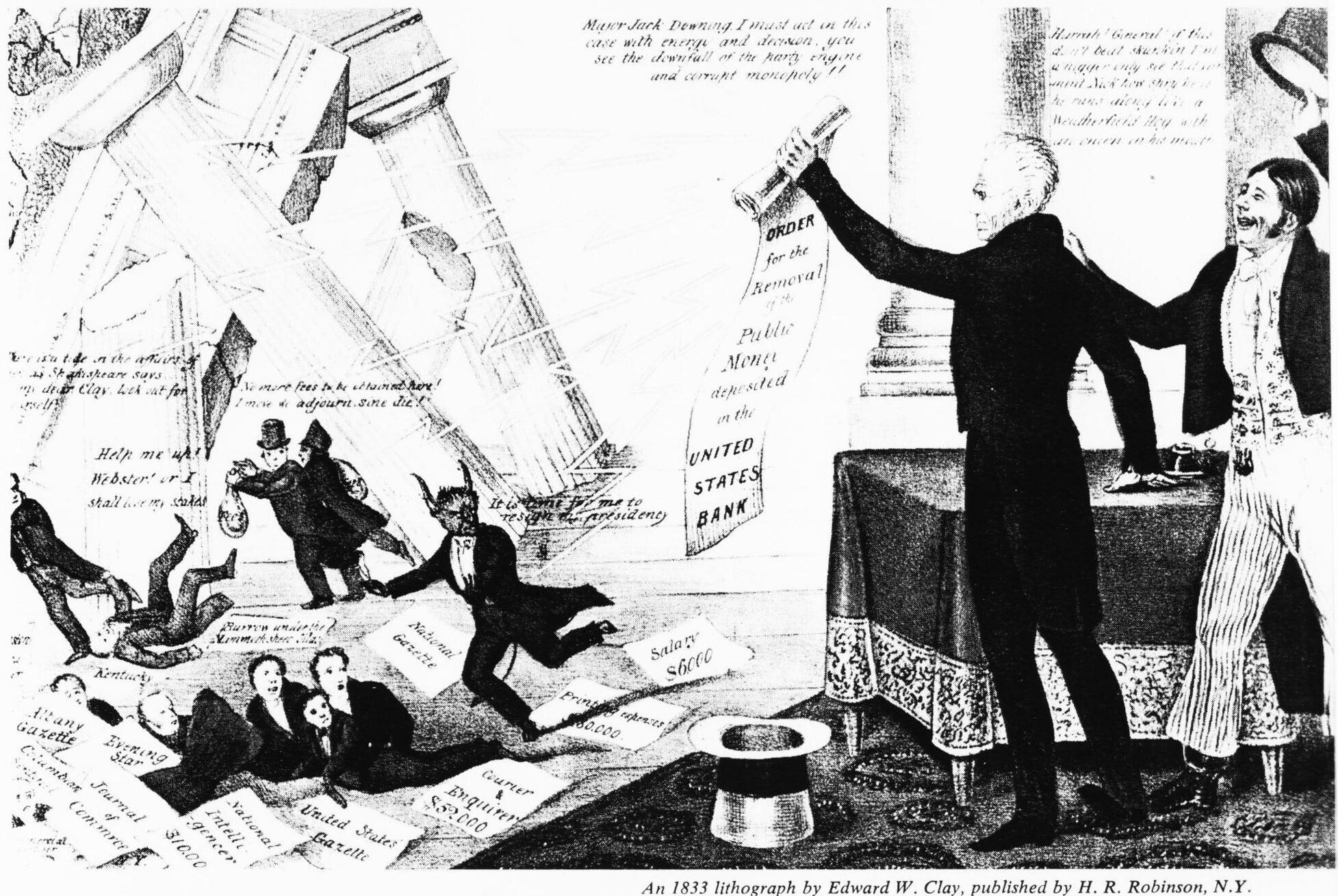

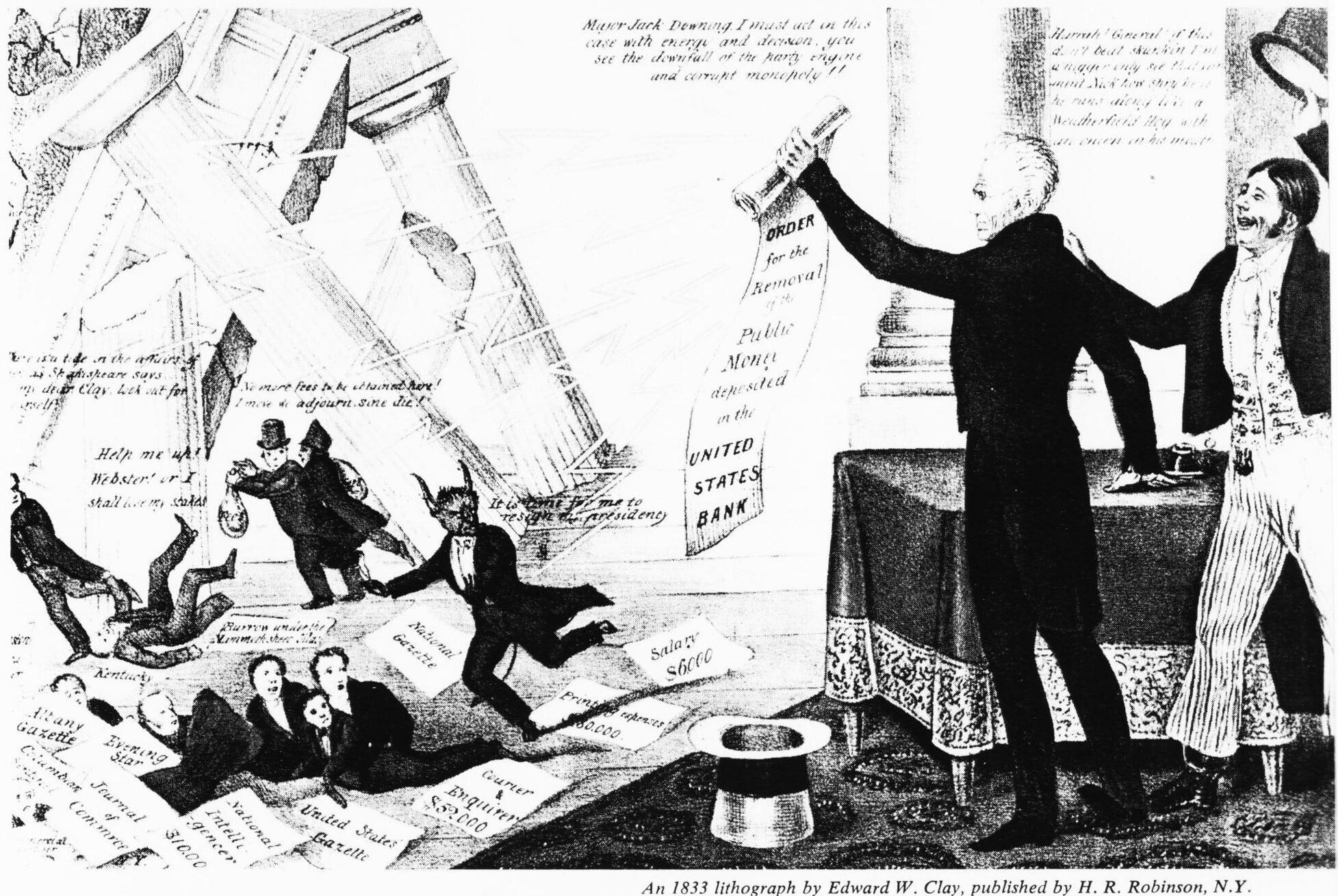

Collapse of the international financial system

On July 10, 1832, US President Andrew Jackson vetoed the bill for the refinancing of the

On July 10, 1832, US President Andrew Jackson vetoed the bill for the refinancing of the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Second Report on Public Credit, Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January ...

, causing a depression in the Anglo-American world. This was worsened in Upper Canada by bad wheat harvests in 1836 and farmers were unable to pay their debts. Most banks – including the Bank of Upper Canada – suspended payments by July 1837 and successfully obtained government support while ordinary farmers and the poor did not. One fifth of British immigrants to Upper Canada were impoverished and most immigrant farmers lacked the capital to pay for purchased land. Debt collection laws allowed them to be jailed indefinitely until they paid their loans to merchants. In March 1837 the Tories passed a law making it cheaper to sue farmers by allowing city merchants to sue in the middle of harvest. If the farmer refused to come to court in Toronto, they would automatically forfeit the case and their property subjected to a sheriff's sale.

Among the more than 150 lawsuits they launched that year, the Bank of Upper Canada, sued Sheldon, Dutcher & Co., a foundry and Toronto's largest employer with over 80 employees in late 1836, bankrupting the company. Mackenzie's first plan for rebellion involved calling on Sheldon & Dutcher's men to storm the city hall, where the militia's guns were stored.

Budget of Upper Canada

The Reformers were incensed at the debt that theFamily Compact

The Family Compact was a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in Upper Canada (today's Ontario) from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was the Upper Canadian equivalent of the Château Clique in L ...

incurred as the results of general improvements to the province, such as the Welland Canal

The Welland Canal is a ship canal in Ontario, Canada, and part of the St. Lawrence Seaway and Great Lakes Waterway. The canal traverses the Niagara Peninsula between Port Weller, Ontario, Port Weller on Lake Ontario, and Port Colborne on Lak ...

.

The Upper Canada legislature refused to pass a supply bill

In the Westminster system (and, colloquially, in the United States), a money bill or supply bill is a bill that solely concerns taxation or government spending (also known as appropriation of money), as opposed to changes in public law.

Conv ...

in 1836 after Bond Head refused to implement responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

reforms. In retaliation Bond Head refused to sign any bills passed by the assembly, including public work projects. This contributed to economic hardship and increased unemployment throughout the province.

Planning

Mackenzie gathered reformers on July 28 and 31, 1837 to discuss their grievances with the government. The meeting created the Committee of Vigilance and signed a declaration urging every community to send delegates to a congress inToronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

and discuss remedies for their concerns. Mackenzie printed the declaration in his newspaper and toured communities north of Toronto to encourage citizens to make similar declarations. Farmers organised target practice sessions and forges in the Home District

The Home District was one of four districts of the Province of Quebec created in 1788 in the western reaches of the Montreal District and detached in 1791 to create the new colony of Upper Canada. It was abolished with the adoption of the county ...

and Simcoe County

Simcoe County is a county and census division located in the central region of Ontario, Canada. The county is located north of the Greater Toronto Area, and forms the north western edge of the Golden Horseshoe. The county seat is located in Mi ...

created weapons for the rebellion.

On October 9, 1837, a messenger from the Patriotes of Lower Canada informed Mackenzie that the rebellion in Lower Canada was going to begin. Mackenzie gathered reformers at John Doel's brewery and proposed kidnapping Bond Head, bringing him to city hall and forcing him to let the Legislature choose the members of the Executive Council. If Bond refused, they would declare independence from the British Empire. Reformers such as Thomas David Morrison opposed this plan and the meeting ended without consensus on what to do next.

The next day Mackenzie convinced John Rolph

John Rolph (4 March 1793 – 19 October 1870) was a Canadian physician, lawyer, and political figure. As a politician, he was considered the leader of the Reform faction in the 1820s and helped plan the Upper Canada Rebellion. As a doctor, h ...

that a rebellion could be successful and happen without anyone being killed. Rolph convinced Morrison to support the rebellion but they also told Mackenzie to get confirmation of support from rural communities. Mackenzie sought out support in rural communities but he also proclaimed that an armed rebellion would happen on December 7 and assigned Samuel Lount

Samuel Lount (September 24, 1791 – April 12, 1838) was a blacksmith, farmer, magistrate and member of the Legislative Assembly in the province of Upper Canada for Simcoe County from 1834 to 1836. He was an organizer of the failed Upper Ca ...

and Anthony Anderson as commanders. Rolph and Morrison were reluctant about the plan so Mackenzie sought Anthony Van Egmond

Anthony Van Egmond (born Antonij Jacobi Willem Gijben, 10 March 17785 January 1838) was purportedly a Dutch Napoleonic War veteran. He became one of the first settlers and business people in the Huron Tract in present-day southwestern Ontario ...

to help lead the armed forces.

In November 1837, in the lead-up to the Political Union's Constitutional Convention, Mackenzie published a satire in the ''Constitution'', a round table discussion by John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

, George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, Oliver Goldsmith

Oliver Goldsmith (10 November 1728 – 4 April 1774) was an Anglo-Irish people, Anglo-Irish poet, novelist, playwright, and hack writer. A prolific author of various literature, he is regarded among the most versatile writers of the Georgian e ...

and William Pitt and others. As part of this satire, he published a draft republican constitution for the State of Upper Canada that closely resembled the objectives in the constitution of the Canadian Alliance Society in 1834. Mackenzie printed broadsheets listing grievances and a call to arms to communities surrounding Toronto. Mackenzie also printed handbills declaring independence which were distributed to citizens north of Toronto.

Counter-rebellion planning

Bond Head did not believe the reports that stated the severity of resources and discontent gathered by the rebels. In November 1837, James Fitzgibbon was concerned about soldiers leaving Upper Canada going to quell theLower Canada Rebellion

The Lower Canada Rebellion (), commonly referred to as the Patriots' Rebellion () in French, is the name given to the armed conflict in 1837–38 between rebels and the colonial government of Lower Canada (now southern Quebec). Together wit ...

and urged Bond Head to keep some troops for protection, which was refused. Fitzgibbon's call to arm a militia was also denied and he refused an armed guard at the Government's House and City Hall. After the Battle of Saint-Denis Fitzgibbon prepared a list of men that he could contact personally if a rebellion began in Toronto. The mayor of Toronto

The mayor of Toronto is the head of Toronto City Council and chief executive officer of the Municipal government of Toronto, municipal government. The mayor is elected alongside city council every four years on the fourth Monday of October; t ...

refused to ring the City Hall bell if a rebellion began because he felt Fitzgibbon was causing unnecessary concern over a possible revolt.

A Tory supporter obtained a copy of Mackenzie's declaration and showed it to authorities in Toronto. Government officials met at the Lieutenant Governor's residence on December 2 to discuss how to stop rumours of a rebellion. Fitzgibbon warned the men of rebels forging pikes north of the city and he was appointed adjutant general of the militia.

Confrontation

Toronto Rebellion

Rolph tried to warn Mackenzie about the warrant for his arrest but could not find him so delivered the message to Lount instead. Upon receiving Rolph's message Lount marched a group of rebels into Toronto for December 4. When hearing about this change, Mackenzie quickly tried to send a messenger to Lount to tell him not to arrive until December 7 but was unable to reach Lount in time. The men gathered at Montgomery's Tavern but were disappointed at the lack of preparation and the failure of the Lower Canada rebels. Although Lount wanted to launch an attack that night, other rebels leaders rejected that plan so that the troops could rest after their march and they could get information from Rolph about the status of rebels who lived in Toronto. A loyalist named Robert Moodie saw the large gathering at Montgomery's Tavern and rode towards Toronto to warn the officials. The rebels set up a roadblock south of the tavern on Yonge Street that Moodie tried riding through. He was wounded in an ensuing battle and taken to the tavern, where he died several hours later in severe pain. Another horseman saw the rebel's march into Toronto and notified Fitzgibbon, who tried unsuccessfully to have officials take action. On December 4, Mackenzie and other rebels were patrolling the area and encountered Alderman John Powell and Archibald Macdonald. Mackenzie took both men prisoner but did not search them for weapons as they gave their word that they did not have any. As they were approaching Montgomery's Tavern Powell mortally shot Anthony Anderson in the neck and escaped back to Toronto to report to Bond Head. The rebel leaders met that night to discuss who would become the rebellion's leader after the death of Anderson and Lount's refusal to lead on his own. It was decided that Mackenzie would become the leader. At noon on December 5, Mackenzie gathered the rebels and marched them towards Toronto. Meanwhile, Bond Head proposed a negotiating session with rebel leaders to Marshall Spring Bidwell, who declined. Bond Head then offered a negotiation with Rolph, who accepted. Rolph andRobert Baldwin

Robert Baldwin (May 12, 1804 – December 9, 1858) was an Upper Canadian lawyer and politician who with his political partner Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine of Lower Canada, led the first responsible government ministry in the Province of Canada. ...

met the rebel troops at Gallows Hill and stated the government's proposal of full amnesty to the rebels if they dispersed immediately. Lount and Mackenzie asked that this offer be presented in a written document and a convention be organised to discuss the province's policies. When Rolph and Baldwin returned to Bond Head, they were informed that the government's offer had been withdrawn. Rolph and Baldwin relayed the rejection to the rebels, and Rolph told Mackenzie that they should attack as soon as possible because the city was poorly defended. Instead, Mackenzie spent the day burning down the house of Bank of Upper Canada official and questioning the loyalty of his troops.

A few hours later Rolph sent a messenger to Mackenzie that Toronto rebels were ready for their arrival to the city and Mackenzie marched his troops towards Toronto. A group of twenty-six men led by Samuel Jarvis met the rebels on their march and fired upon them before running away. The rebels believed there were several battalions of troops firing upon them and several ran away. Lount encouraged some riflemen to return fire before realising that the enemy had left the battlefield. Lount and the riflemen marched to find the rebels who fled and found Mackenzie trying to convince the rebels to continue their path towards Toronto. The rebels refused to march until daylight.

On Tuesday night MacNab arrived in Toronto with sixty men from the Hamilton area. Morrison was arrested and charged with treason while Rolph sent a letter encouraging Mackenzie to send the rebels home then fled to the United States. Mackenzie ignored the letter and continued his plan for rebellion.

On Wednesday morning Peter Matthews arrived at the tavern with sixty men, but Mackenzie could still not convince the rebel forces to march towards Toronto. Instead, they decided to wait for Anthony Van Egmond

Anthony Van Egmond (born Antonij Jacobi Willem Gijben, 10 March 17785 January 1838) was purportedly a Dutch Napoleonic War veteran. He became one of the first settlers and business people in the Huron Tract in present-day southwestern Ontario ...

to lead the rebellion into Toronto. The rebels raided a mail coach, stole the passenger's money and looked for information about the progress of the rebellion in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, Upper Canada. Mackenzie also attacked other travellers and robbed them or questioned them about the revolt.

The government organised a council of war and agreed to attack the rebels on December 7. Fitzgibbon was appointed commander of the government's forces. Although initially believing the government's position was untenable he was inspired by a company of men that formed to defend the government. At noon Bond Head ordered that the troops, consisting of 1200 men and two cannons, march towards the rebels.

Battle of Montgomery's Tavern

Anthony Van Egmond

Anthony Van Egmond (born Antonij Jacobi Willem Gijben, 10 March 17785 January 1838) was purportedly a Dutch Napoleonic War veteran. He became one of the first settlers and business people in the Huron Tract in present-day southwestern Ontario ...

arrived at the tavern on December 7 and encouraged the rebel leaders to disperse, as he felt the rebellion would not be a success. His advice was rejected, so he proposed entrenching and defending their position at the tavern. Mackenzie disagreed and wanted to attack the government troops. They agreed to send sixty men to the Don Bridge to divert government troops. That afternoon a sentinel reported the government force's arrival from Gallows Hill. At this point only 200 men at Montgomery's Tavern were armed. The armed forces were split into two companies and went to fields on both sides of Yonge Street. The rebels without arms were sent to the tavern with their prisoners.

The government forces also split into two companies when the rebels fired upon them. The rebels dispersed in a panic after the first round of firing thinking the rebel's front row had been killed when they were simply dropping to the ground to allow those behind them to fire. The government continued their march and at Montgomery's Tavern a cannon shot into the dining room window. The rebels fled north and the morale of the rebellion was irreparably broken. Bond Head ordered the tavern to be burned down and the rebels arrested.

London Rebellion

News of the intended rebellion had reached London, Upper Canada and its surrounding townships by December 7. It was initially thought that the Toronto rebellion was successful, contributing toCharles Duncombe Charles Duncombe may refer to:

* Charles Duncombe (English banker) (1648–1711), English banker, MP and Lord Mayor

* Charles Duncombe, 1st Baron Feversham (1764–1841), English MP

*Charles Duncombe (Upper Canada Rebellion) (1792–1867), American ...

wanting to rise up as well. Upon hearing more details about the rebellion in Toronto, Duncombe convened a series of public meetings to spread news of the supposed atrocities committed by Bond Head against all suspected reformers to help increase anti-government support. It is estimated that there were between 400 and 500 rebels who assembled under Duncombe.

Colonel Allan MacNab

Sir Allan Napier MacNab, 1st Baronet (19 February 1798 – 8 August 1862) was a Canadian political leader, land speculator and property investor, lawyer, soldier, and militia commander who served in the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada t ...

, who had just finished leading Upper Canadian militiamen during the Battle of Montgomery's Tavern, was sent to engage Duncombe's uprising. He left Hamilton, Ontario

Hamilton is a port city in the Canadian Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Ontario. Hamilton has a 2021 Canadian census, population of 569,353 (2021), and its Census Metropolitan Area, census metropolitan area, which encompasses ...

on December 12 and arrived in Brantford

Brantford ( 2021 population: 104,688) is a city in Ontario, Canada, founded on the Grand River in Southwestern Ontario. It is surrounded by Brant County but is politically separate with a municipal government of its own that is fully indep ...

on December 13. Although many rebels, including Duncombe, had fled prior to the upcoming battle due to hearing about the failure of Mackenzie in Toronto and general disorganization, there were still some present in Scotland, Ontario and MacNab commenced his attack on Scotland on December 14, causing the remaining rebels to flee after only a few shots were fired. The victorious Tory supporters burned homes and farms of known rebels and suspected supporters. In the 1860s, some of the former rebels were compensated by the Canadian government for their lost property in the rebellion aftermath.

Patriot war

The rebels from Toronto travelled to the United States in groups of two. Mackenzie, Duncombe, Rolph and 200 supporters fled to

The rebels from Toronto travelled to the United States in groups of two. Mackenzie, Duncombe, Rolph and 200 supporters fled to Navy Island

Navy Island is a small, uninhabited island in the Niagara River in the province of Ontario, managed by Parks Canada as a National Historic Sites of Canada, National Historic Site of Canada. It is located about 4.5 kilometres (2+3⁄4 miles) ups ...

in the Niagara River

The Niagara River ( ) flows north from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario, forming part of the border between Ontario, Canada, to the west, and New York, United States, to the east. The origin of the river's name is debated. Iroquoian scholar Bruce T ...

and declared themselves the Republic of Canada

The Republic of Canada was a government proclaimed by William Lyon Mackenzie on December 5, 1837. The self-proclaimed government was established on Navy Island in the Niagara River in the latter days of the Upper Canada Rebellion.

History

In t ...

on December 13. They obtained supplies from supporters in the United States, resulting in British reprisals (see Caroline affair). On January 13, 1838, under attack by British armaments, the rebels fled. Mackenzie went to the United States mainland where he was arrested for violating the Neutrality Act.

The rebels continued their raids into Canada using the U.S. as a base of operations and, in cooperation with the U.S. Hunters' Lodges, dedicated themselves to the overthrow of British rule in Canada. The raids did not end until the rebels and Hunters were defeated at the Battle of the Windmill, just eleven months after the initial battle at Montgomery's Tavern.

Consequences: execution or transportation

The British government was concerned about the rebellion, especially in light of the strong popular support for the rebels in the United States and the

The British government was concerned about the rebellion, especially in light of the strong popular support for the rebels in the United States and the Lower Canada Rebellion

The Lower Canada Rebellion (), commonly referred to as the Patriots' Rebellion () in French, is the name given to the armed conflict in 1837–38 between rebels and the colonial government of Lower Canada (now southern Quebec). Together wit ...

. Bond Head was recalled in late 1837 and replaced with Sir George Arthur

Sir George Arthur, 1st Baronet (21 June 1784 – 19 September 1854) was a British colonial administrator who was Lieutenant Governor of British Honduras from 1814 to 1822 and of Van Diemen's Land (present-day Tasmania) from 1824 to 1836. ...

who arrived in Toronto in March 1838. Parliament also sent Lord Durham to become Governor-in-Chief of the British North American colonies,Lambton, John George, 1st Earl of Durham, in the ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online'', University of Toronto, Université Laval, 2000/ref> so that Arthur reported to Durham. Durham was assigned to report on the grievances among the British North American colonists and find a way to appease them. His report eventually led to greater autonomy in the Canadian colonies and the union of Upper and Lower Canada into the

Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in British North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report ...

in 1840.

Over 800 people were arrested after the rebellion for being Reform sympathisers. Van Egmond died of an illness he acquired while imprisoned while Lount and Peter Matthews were sentenced to the gallows for leading the rebellion. Other rebels were also sentenced to hang and ninety-two men were sent to Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

. A group of rebels escaped their prison at Fort Henry and travelled to the United States. A general pardon for everyone but Mackenzie was issued in 1845, and Mackenzie himself was pardoned in 1849 and allowed to return to Canada, where he resumed his political career.

Historical significance

John Charles Dent, writing in 1885, said the rebellion was a reaction from the public of the government mismanagement of the minority ruling elite. Frederick Armstrong believed the rebellion was a reaction to patronage afforded to members of the Family Compact after winning the 1836 election. Dent wrote that the rebellion caused England to notice the concerns of Canadian reformers and reconsider their colonial rule of the province. He thought the rebellion hastened the changes Reformers advocated by drawing attention to the province from theColonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created in 1768 from the Southern Department to deal with colonial affairs in North America (particularly the Thirteen Colo ...

and the production of the ''Durham Report''.

Paul Romney argued that the above assessments are a failure of historical imagination and the outcome of an explicit strategy adopted by reformers in the face of charges of disloyalty to Britain in the wake of the Rebellions of 1837. In recounting the “myths of responsible government”, Romney opined that after the ascendancy of Loyalism as the dominant political ideology of Upper Canada any demand for democracy or for responsible government became a challenge to colonial sovereignty. In his view, the linkage of the "fight for responsible government" with disloyalty was solidified by the Rebellion of 1837, as reformers took up arms to finally break the "baneful domination" of the mother country. Struggling to avoid the charge of sedition, reformers later purposefully obscured their true aims of independence from Britain and focused on their grievances against the Family Compact. Thus, responsible government became a "pragmatic" policy of alleviating local abuses, rather than a revolutionary anti-colonial moment.

William Kilbourn stated that the removal of Radicals from Upper Canada politics, either through execution or their retreat to the United States, allowed the Clear Grits to be formed as a more moderate political force that had fewer disagreements with the Tories than the reformers.

See also

* Benjamin Milliken II *History of Canada

The history of Canada covers the period from the arrival of the Paleo-Indians to North America thousands of years ago to the present day. The lands encompassing present-day Canada have been inhabited for millennia by Indigenous peoples, with d ...

* Rebellions of 1837

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * *Further reading

William Lyon Mackenzie

Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, Biographi.ca * "Rebellion in Upper Canada, 1837" by J. Edgar Re

"MHS Transactions: Rebellion in Upper Canada, 1837"

Mhs.mb.ca * Brown, Richard. ''Rebellion in Canada, 1837–1885: Autocracy, Rebellion and Liberty'' (Vol. 1) (2012)

excerpt volume 1

''Rebellion in Canada, 1837–1885, Volume 2: The Irish, the Fenians and the Metis'' (2012

excerpt for vol. 2

* Ducharme, Michel

"Closing the Last Chapter of the Atlantic Revolution: The 1837–38 Rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada,"

''Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society'' 116(2): 413–430; (2006) * Dunning, Tom. "The Canadian Rebellions of 1837 and 1838 as a Borderland War: A Retrospective," ''Ontario History'' (2009) 101#2 pp 129–141. * Mann, Michael. ''A Particular Duty: The Canadian Rebellions, 1837–1839'' (1986) * Read, Colin. ''The rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada'' (The Canadian Historical Association historical booklet) (1988), short pamphlet * Tiffany, Orrin Edward. ''The Relations of the United States to the Canadian Rebellion of 1837–1838'' (2010)

"The story of the Upper Canadian rebellion

. C. Blackett Robinson, Toronto * Charles Lindsey, ''The Life and Times of William Lyon Mackenzie and the Rebellion of 1837–38.'' 1862; cited by Betsy Dewar Boyce, ''The Rebels of Hastings'', 1992.

Primary sources

Proceedings of the Legislative Council of Upper Canada on the bill sent up from the House of Assembly, entitled, An act to amend the jury laws of this province

(February 25, 1836) * Colin Read and Ronald J. Stagg, eds.

The Rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada: A collection of documents

' (The Publications of the Champlain Society, Ontario Series XII, 1985), 471pp (with free online access). * Greenwood,F. Murray, and Barry Wright (2 vol 1996, 2002

Canadian state trials – Rebellion and invasion in the Canadas, 1837–1839

Society for Canadian Legal History by University of Toronto Press,

External links

by William Lyon Mackenzie, 1839 from th

Ontario Time Machine

Samuel Lount Film

an

Samuel Lount's History

The feature film is about the injustice of the system under the Family Compact's rule. * . by Serge Gorelsky

"Upper canada rebellion

. www.canadianencyclopedia.ca {{British colonial campaigns Political history of Canada December 1837 Political violence in Canada