13 Colonies on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Thirteen Colonies were the

In 1606, King

In 1606, King

#

#

Beginning in 1609, Dutch traders established fur trading posts on the

Beginning in 1609, Dutch traders established fur trading posts on the

In 1738, an incident involving a Welsh mariner named Robert Jenkins sparked the

In 1738, an incident involving a Welsh mariner named Robert Jenkins sparked the

In response, the colonies formed bodies of elected representatives known as Provincial Congresses, and colonists began to boycott imported British merchandise. Later in 1774, 12 colonies sent representatives to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. During the Second Continental Congress, the remaining colony of Georgia sent delegates as well.

Massachusetts Governor Thomas Gage feared a confrontation with the colonists; he requested reinforcements from Britain, but the British government was not willing to pay for the expense of stationing tens of thousands of soldiers in the Thirteen Colonies. Gage was instead ordered to seize Patriot arsenals. He dispatched a force to march on the arsenal at Concord, Massachusetts, but the Patriots learned about it and blocked their advance. The Patriots repulsed the British force at the April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, then lay Siege of Boston, siege to Boston.

By spring 1775, all royal officials had been expelled, and the

In response, the colonies formed bodies of elected representatives known as Provincial Congresses, and colonists began to boycott imported British merchandise. Later in 1774, 12 colonies sent representatives to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. During the Second Continental Congress, the remaining colony of Georgia sent delegates as well.

Massachusetts Governor Thomas Gage feared a confrontation with the colonists; he requested reinforcements from Britain, but the British government was not willing to pay for the expense of stationing tens of thousands of soldiers in the Thirteen Colonies. Gage was instead ordered to seize Patriot arsenals. He dispatched a force to march on the arsenal at Concord, Massachusetts, but the Patriots learned about it and blocked their advance. The Patriots repulsed the British force at the April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, then lay Siege of Boston, siege to Boston.

By spring 1775, all royal officials had been expelled, and the

Higher education was available for young men in the north, and most students were aspiring Protestant ministers. Nine institutions of higher education were chartered during the colonial era. These colleges, known collectively as the colonial colleges were Harvard College, New College (Harvard), the College of William & Mary, Yale University, Yale College (Yale), the Princeton College, College of New Jersey (Princeton), Columbia University, King's College (Columbia), the University of Pennsylvania, College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania), the Brown University, College of Rhode Island (Brown), Rutgers College, Queen's College (Rutgers) and Dartmouth College. The College of William & Mary and Queen's College later became public institutions while the other institutions account for seven of the eight private Ivy League universities.

With the exception of the College of William and Mary, these institutions were all located in New England and the Middle Colonies. The southern colonies held the belief that the family had the responsibility of educating their children, mirroring the common belief in Europe. Wealthy families either used tutors and governesses from Britain or sent children to school in England. By the 1700s, university students based in the colonies began to act as tutors.

Most New England towns sponsored public schools for boys, but public schooling was rare elsewhere. Girls were educated at home or by small local private schools, and they had no access to college. Aspiring physicians and lawyers typically learned as apprentices to an established practitioner, although some young men went to medical schools in Scotland.

Higher education was available for young men in the north, and most students were aspiring Protestant ministers. Nine institutions of higher education were chartered during the colonial era. These colleges, known collectively as the colonial colleges were Harvard College, New College (Harvard), the College of William & Mary, Yale University, Yale College (Yale), the Princeton College, College of New Jersey (Princeton), Columbia University, King's College (Columbia), the University of Pennsylvania, College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania), the Brown University, College of Rhode Island (Brown), Rutgers College, Queen's College (Rutgers) and Dartmouth College. The College of William & Mary and Queen's College later became public institutions while the other institutions account for seven of the eight private Ivy League universities.

With the exception of the College of William and Mary, these institutions were all located in New England and the Middle Colonies. The southern colonies held the belief that the family had the responsibility of educating their children, mirroring the common belief in Europe. Wealthy families either used tutors and governesses from Britain or sent children to school in England. By the 1700s, university students based in the colonies began to act as tutors.

Most New England towns sponsored public schools for boys, but public schooling was rare elsewhere. Girls were educated at home or by small local private schools, and they had no access to college. Aspiring physicians and lawyers typically learned as apprentices to an established practitioner, although some young men went to medical schools in Scotland.

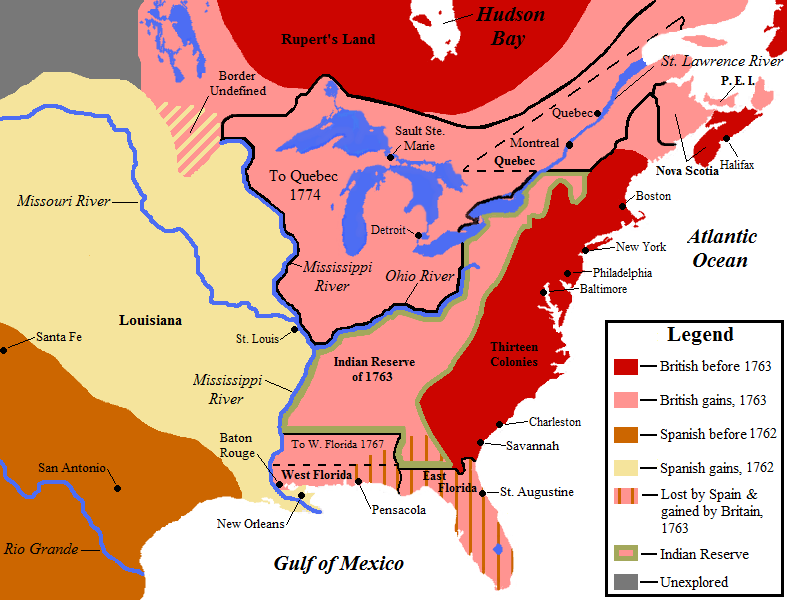

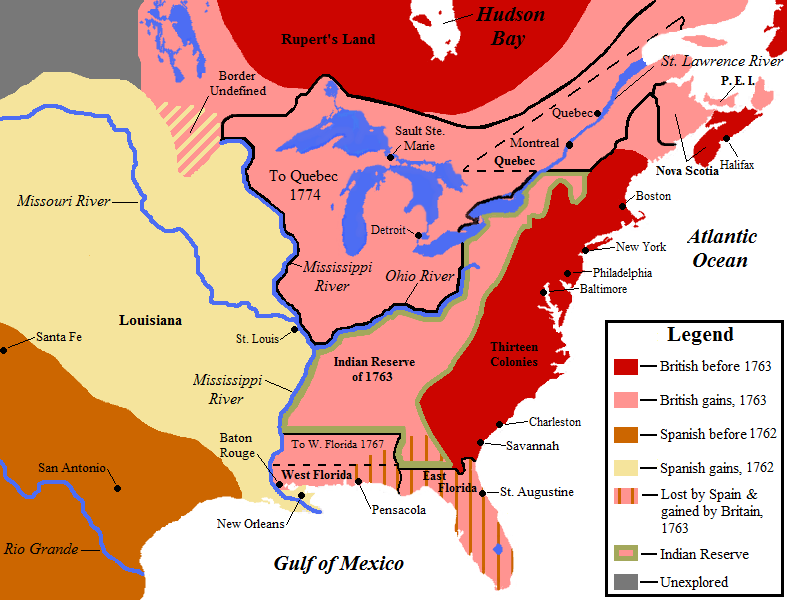

Besides the grouping that became known as the "thirteen colonies",

Britain in the late-18th century had another dozen colonial possessions in the British America, New World surrounding the 13 colonies. The British West Indies, Newfoundland Colony, Newfoundland, the Province of Quebec (1763–1791), Province of Quebec,

Besides the grouping that became known as the "thirteen colonies",

Britain in the late-18th century had another dozen colonial possessions in the British America, New World surrounding the 13 colonies. The British West Indies, Newfoundland Colony, Newfoundland, the Province of Quebec (1763–1791), Province of Quebec,

online

* Landsman, Ned C. ''Crossroads of Empire: The Middle Colonies in British North America'' (2011). * * * * * * Ratcliffe, Donald. "The right to vote and the rise of democracy, 1787–1828." ''Journal of the Early Republic'' 33.2 (2013): 219–254

online

* * * * * *

Alt URL

* * * *

Alt URL

* *

* [http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/mb?a=listis;c=855228657 840+ volumes of colonial records]; useful for advanced scholarship {{Authority control Thirteen Colonies, 1732 establishments in the British Empire 1776 disestablishments in the British Empire Colonial settlements in North America Colonial United States (British) English colonization of the Americas Former British colonies and protectorates in the Americas Former colonies in North America Former regions and territories of the United States Former territorial entities in North America States and territories disestablished in 1776

British colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by England, and then Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English and later British Empire. There was usually a governor to represent the Crown, appointed by the British monarch on ...

on the Atlantic coast of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

(1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 contiguo ...

.

The Thirteen Colonies in their traditional groupings were: the New England Colonies (New Hampshire

New Hampshire ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

, Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

, and Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

); the Middle Colonies ( New York, New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, and Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

); and the Southern Colonies

The Southern Colonies within British America consisted of the Province of Maryland, the Colony of Virginia, the Province of Carolina (in 1712 split into North and South Carolina), and the Province of Georgia. In 1763, the newly created colonies ...

(Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

, and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

). These colonies were part of British America

British America collectively refers to various British colonization of the Americas, colonies of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and its predecessors states in the Americas prior to the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War in 1 ...

, which also included territory in The Floridas, the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

, and what is today Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

.

The Thirteen Colonies were separately administered under the Crown, but had similar political, constitutional, and legal systems, and each was dominated by Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

English-speakers. The first of the colonies, Virginia, was established at Jamestown, in 1607. Maryland, Pennsylvania, and the New England Colonies were substantially motivated by their founders' concerns related to the practice of religion. The other colonies were founded for business and economic expansion. The Middle Colonies were established on the former Dutch colony of New Netherland

New Netherland () was a colony of the Dutch Republic located on the East Coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva Peninsula to Cape Cod. Settlements were established in what became the states ...

.

Between 1625 and 1775, the colonial population grew from 2 thousand to 2.4 million, largely displacing the region's Native Americans. The population included people subject to a system of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, which was legal in all of the colonies. In the 18th century, the British government operated under a policy of mercantilism

Mercantilism is a economic nationalism, nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources ...

, in which the central government administered its colonies for Britain's economic benefit.

The 13 colonies had a degree of self-governance and active local elections, and they resisted London's demands for more control over them. The French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

(1754–1763) against France and its Indian allies led to growing tensions between Britain and the 13 colonies. During the 1750s, the colonies began collaborating with one another instead of dealing directly with Britain. With the help of colonial printers and newspapers, these inter-colonial activities and concerns were shared and led to calls for protection of the colonists' " Rights as Englishmen", especially the principle of " no taxation without representation".

Late 18th century conflicts with the British government over taxes and rights led to the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

, in which the Thirteen Colonies joined for the first time to form the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

and raised the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

, declaring independence in 1776. They fought the Revolutionary War with the aid of the Kingdom of France and, to a much lesser degree, the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

and the Kingdom of Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

.

British colonies

In 1606, King

In 1606, King James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 unti ...

granted charters to both the Plymouth Company

The Plymouth Company, officially known as the Virginia Company of Plymouth, was a company chartered by King James in 1606 along with the Virginia Company of London with responsibility for colonizing the east coast of America between latitud ...

and the London Company

The Virginia Company of London (sometimes called "London Company") was a division of the Virginia Company with responsibility for colonizing the east coast of North America between latitudes 34° and 41° N.

History Origins

The territory ...

for the purpose of establishing permanent settlements in America. The London Company established the Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia was a British Empire, British colonial settlement in North America from 1606 to 1776.

The first effort to create an English settlement in the area was chartered in 1584 and established in 1585; the resulting Roanoke Colo ...

in 1607, the first permanently settled English colony on the continent. The Plymouth Company founded the Popham Colony on the Kennebec River

The Kennebec River (Abenaki language, Abenaki: ''Kinəpékʷihtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 30, 2011 natural river within the U.S. state of Ma ...

, but it was short-lived. The Plymouth Council for New England

The Council for New England was a 17th-century English joint stock company to which James I of England awarded a royal charter, with the purpose of expanding his realm over parts of North America by establishing colonial settlements.

The Coun ...

sponsored several colonization projects, culminating with Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes spelled Plimouth) was the first permanent English colony in New England from 1620 and the third permanent English colony in America, after Newfoundland and the Jamestown Colony. It was settled by the passengers on t ...

in 1620 which was settled by English Puritan separatists, known today as the Pilgrims. The Dutch, Swedish, and French also established successful American colonies at roughly the same time as the English, but they eventually came under the English crown. The Thirteen Colonies were complete with the establishment of the Province of Georgia

The Province of Georgia (also Georgia Colony) was one of the Southern Colonies in colonial-era British America. In 1775 it was the last of the Thirteen Colonies to support the American Revolution.

The original land grant of the Province of G ...

in 1732, although the term "Thirteen Colonies" became current only in the context of the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

.

In London, beginning in 1660, all colonies were governed through a state department known as the Southern Department, and a committee of the Privy Council called the Board of Trade and Plantations. In 1768, a specific state department was created for America, but it was disbanded in 1782 when the Home Office

The Home Office (HO), also known (especially in official papers and when referred to in Parliament) as the Home Department, is the United Kingdom's interior ministry. It is responsible for public safety and policing, border security, immigr ...

took responsibility.

New England colonies

Province of Massachusetts Bay

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a colony in New England which became one of the thirteen original states of the United States. It was chartered on October 7, 1691, by William III and Mary II, the joint monarchs of the kingdoms of Eng ...

, chartered as a royal colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by England, and then Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English and later British Empire. There was usually a governor to represent the Crown, appointed by the British monarch on ...

in 1691

#* Popham Colony, established in 1607; abandoned in 1608

#* Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes spelled Plimouth) was the first permanent English colony in New England from 1620 and the third permanent English colony in America, after Newfoundland and the Jamestown Colony. It was settled by the passengers on t ...

, established in 1620; merged with Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1691

#* Province of Maine

The Province of Maine refers to any of the various English overseas possessions, English colonies established in the 17th century along the northeast coast of North America, within portions of the present-day U.S. states of Maine, New Hampshire ...

, patent issued in 1622 by Council for New England; patent reissued by Charles I in 1639; absorbed by Massachusetts Bay Colony by 1658

#* Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of M ...

, established in 1628; merged with Plymouth Colony in 1691

#Province of New Hampshire

The Province of New Hampshire was an English colony and later a British province in New England. It corresponds to the territory between the Merrimack and Piscataqua rivers on the eastern coast of North America. It was named after the Englis ...

, established in 1629; merged with Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1641; chartered as royal colony in 1679

#Connecticut Colony

The Connecticut Colony, originally known as the Connecticut River Colony, was an English colony in New England which later became the state of Connecticut. It was organized on March 3, 1636, as a settlement for a Puritans, Puritan congregation o ...

, established in 1636; chartered as royal colony in 1662

#*Saybrook Colony

The Saybrook Colony was a short-lived English colony established in New England in 1635 at the mouth of the Connecticut River in what is today Old Saybrook, Connecticut. Saybrook was founded by a group of Puritan noblemen as a potential politic ...

, established in 1635; merged with Connecticut Colony in 1644

#*New Haven Colony

New Haven Colony was an English colony from 1638 to 1664 that included settlements on the north shore of Long Island Sound, with outposts in modern-day New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. The colony joined Connecticut Colony in 16 ...

, established in 1638; merged with Connecticut Colony in 1664

#Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was an English colony on the eastern coast of America, founded in 1636 by Puritan minister Roger Williams after his exile from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It became a haven for religious d ...

chartered as royal colony in 1663

#*Providence Plantations established by Roger Williams

Roger Williams (March 1683) was an English-born New England minister, theologian, author, and founder of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Pl ...

in 1636

#*Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

established in 1638 by John Clarke, William Coddington, and others

#* Newport established in 1639 after a disagreement and split among the settlers in Portsmouth

#*Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon, Warwickshire, River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined wit ...

established in 1642 by Samuel Gorton

#*These four settlements merged into a single Royal colony in 1663

Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, and New Haven Colonies formed the New England Confederation

The United Colonies of New England, commonly known as the New England Confederation, was a confederal alliance of the New England colonies of Massachusetts Bay Colony, Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth Colony, Plymouth, Saybrook Colony, Saybrook (Conn ...

in 1643, and all New England colonies were included in the Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was a short-lived administrative union of English colonies covering all of New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies, with the exception of the Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvani ...

(1686–1689).

Middle colonies

- Delaware Colony The Delaware Colony, officially known as the three Lower Counties on the Delaware, was a semiautonomous region of the proprietary Province of Pennsylvania and a '' de facto'' British colony in North America. Although not royally sanctioned, ...(before 1776, the ''Lower Counties on Delaware''), established in 1664 asproprietary colony Proprietary colonies were a type of colony in English America which existed during the early modern period. In English overseas possessions established from the 17th century onwards, all land in the colonies belonged to the Crown, which held ul ...

- Province of New York The Province of New York was a British proprietary colony and later a royal colony on the northeast coast of North America from 1664 to 1783. It extended from Long Island on the Atlantic, up the Hudson River and Mohawk River valleys to ..., established as a proprietary colony in 1664; chartered as royal colony in 1686; included in theDominion of New England The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was a short-lived administrative union of English colonies covering all of New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies, with the exception of the Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvani ...(1686–1689)

- Province of New Jersey The Province of New Jersey was one of the Middle Colonies of Colonial history of the United States, Colonial America and became the U.S. state of New Jersey in 1776. The province had originally been settled by Europeans as part of New Netherla ..., established as a proprietary colony in 1664; chartered as a royal colony in 1702 *East Jersey The Province of East Jersey, along with the Province of West Jersey, between 1674 and 1702 in accordance with the Quintipartite Deed, were two distinct political divisions of the Province of New Jersey, which became the U.S. state of New Jersey. ..., established in 1674; merged with West Jersey to re-form Province of New Jersey in 1702; included in the Dominion of New England *West Jersey West Jersey and East Jersey were two distinct parts of the Province of New Jersey. The political division existed for 28 years, between 1674 and 1702. Determination of an exact location for a border between West Jersey and East Jersey was often ..., established in 1674; merged with East Jersey to re-form Province of New Jersey in 1702; included in the Dominion of New England

- Province of Pennsylvania The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn, who received the land through a grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania was derived from ..., established in 1681 as a proprietary colony

Southern colonies

- Colony of Virginia The Colony of Virginia was a British Empire, British colonial settlement in North America from 1606 to 1776. The first effort to create an English settlement in the area was chartered in 1584 and established in 1585; the resulting Roanoke Colo ..., established in 1607 as a proprietary colony; chartered as a royal colony in 1624.

- Province of Maryland The Province of Maryland was an Kingdom of England, English and later British colonization of the Americas, British colony in North America from 1634 until 1776, when the province was one of the Thirteen Colonies that joined in supporting the A ..., established 1632 as a proprietary colony.

- Province of North Carolina The Province of North Carolina, originally known as the Albemarle Settlements, was a proprietary colony and later royal colony of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776.(p. 80) It was one of the five Southern col ..., previously part of the Carolina province (see below) until 1712; chartered as a royal colony in 1729.

- Province of South Carolina The Province of South Carolina, originally known as Clarendon Province, was a province of the Kingdom of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the Thirteen Colonies i ..., previously part of the Carolina province (see below) until 1712; chartered as a royal colony in 1729.

- Province of Georgia The Province of Georgia (also Georgia Colony) was one of the Southern Colonies in colonial-era British America. In 1775 it was the last of the Thirteen Colonies to support the American Revolution. The original land grant of the Province of G ..., established as a proprietary colony in 1732; royal colony from 1752.

Province of Carolina

The Province of Carolina was a colony of the Kingdom of England (1663–1707) and later the Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until the Carolinas were partitioned into North and Sou ...

was initially chartered in 1629 and initial settlements were established after 1651. That charter was voided in 1660 by Charles II and a new charter was issued in 1663, making it a proprietary colony. The Carolina province was divided into separate proprietary colonies, north and south in 1712, before both became royal colonies in 1729.

Earlier, along the coast, the Roanoke Colony

The Roanoke Colony ( ) refers to two attempts by Sir Walter Raleigh to found the first permanent English settlement in North America. The first colony was established at Roanoke Island in 1585 as a military outpost, and was evacuated in 1586. ...

was established in 1585, re-established in 1587, and found abandoned in 1590.

17th century

Southern colonies

The first British colony was Jamestown, established on May 14, 1607, nearChesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

. The business venture was financed and coordinated by the London Virginia Company, a joint-stock company looking for gold. Its first years were extremely difficult, with very high death rates from disease and starvation, wars with local Indians, and little gold. The colony survived and flourished by turning to tobacco as a cash crop.

In 1632, King Charles I granted the charter for the Province of Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an Kingdom of England, English and later British colonization of the Americas, British colony in North America from 1634 until 1776, when the province was one of the Thirteen Colonies that joined in supporting the A ...

to Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore

Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore (8 August 1605 – 30 November 1675) was an English politician and lawyer who was the first List of Proprietors of Maryland, proprietor of Maryland. Born in Kent, England in 1605, he inherited the proprietorsh ...

. Calvert's father had been a prominent Catholic official who encouraged Catholic immigration to the English colonies. The charter offered no guidelines on religion.

The Province of Carolina

The Province of Carolina was a colony of the Kingdom of England (1663–1707) and later the Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until the Carolinas were partitioned into North and Sou ...

was the second attempted English settlement south of Virginia, the first being the failed attempt at Roanoke. It was a private venture, financed by a group of English Lords Proprietors

A lord proprietor is a person granted a royal charter for the establishment and government of an English colony in the 17th century. The plural of the term is "lords proprietors" or "lords proprietary".

Origin

In the beginning of the Europe ...

who obtained a Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

to the Carolinas in 1663, hoping that a new colony in the south would become profitable like Jamestown. Carolina was not settled until 1670, and even then the first attempt failed because there was no incentive for emigration to that area. Eventually, however, the Lords combined their remaining capital and financed a settlement mission to the area led by Sir John Colleton. The expedition located fertile and defensible ground at Charleston, originally Charles Town for Charles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651 and King of England, Scotland, and King of Ireland, Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest su ...

.

Middle colonies

Beginning in 1609, Dutch traders established fur trading posts on the

Beginning in 1609, Dutch traders established fur trading posts on the Hudson River

The Hudson River, historically the North River, is a river that flows from north to south largely through eastern New York (state), New York state. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains at Henderson Lake (New York), Henderson Lake in the ...

, Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and is the longest free-flowing (undammed) river in the Eastern United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for a ...

, and Connecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges into Long Isl ...

, seeking to protect their interests in the fur trade. The Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company () was a Dutch chartered company that was founded in 1621 and went defunct in 1792. Among its founders were Reynier Pauw, Willem Usselincx (1567–1647), and Jessé de Forest (1576–1624). On 3 June 1621, it was gra ...

established permanent settlements on the Hudson River, creating the Dutch colony of New Netherland

New Netherland () was a colony of the Dutch Republic located on the East Coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva Peninsula to Cape Cod. Settlements were established in what became the states ...

.

In 1626, Peter Minuit

Peter Minuit (French language, French: ''Pierre Minuit'', Dutch language, Dutch: ''Peter Minnewit''; 1580 – August 5, 1638) was a Walloons, Walloon merchant and politician who was the 3rd Director of New Netherland, Director of the Dutch Nort ...

purchased the island of Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

from the Lenape

The Lenape (, , ; ), also called the Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada.

The Lenape's historica ...

Indians and established the outpost of New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam (, ) was a 17th-century Dutch Empire, Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''Factory (trading post), fac ...

. Relatively few Dutch settled in New Netherland, but the colony came to dominate the regional fur trade. It also served as the base for extensive trade with the English colonies, and many products from New England and Virginia were carried to Europe on Dutch ships. The Dutch also engaged in the burgeoning Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

, bringing some enslaved Africans to the English colonies in North America, although many more were sent to Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

and Brazil. The West India Company desired to grow New Netherland as it became commercially successful, yet the colony failed to attract the same level of settlement as the English colonies did. Many of those who did immigrate to the colony were English, German, Walloon, or Sephardim

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendan ...

.

In 1638, Sweden established the colony of New Sweden

New Sweden () was a colony of the Swedish Empire between 1638 and 1655 along the lower reaches of the Delaware River in what is now Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Established during the Thirty Years' War when Sweden was a g ...

in the Delaware Valley

The Philadelphia metropolitan area, also known as Greater Philadelphia and informally called the Delaware Valley, the Philadelphia tri-state area, and locally and colloquially Philly–Jersey–Delaware, is a major metropolitan area in the Nor ...

. The operation was led by former members of the Dutch West India Company, including Peter Minuit. New Sweden established extensive trading contacts with English colonies to the south and shipped much of the tobacco produced in Virginia. The colony was conquered by the Dutch in 1655, while Sweden was engaged in the Second Northern War

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of ...

.

Beginning in the 1650s, the English and Dutch engaged in a series of wars, and the English sought to conquer New Netherland. Richard Nicolls

Richard Nicolls ( – 28 May 1672) was an English military officer and colonial administrator who served as the first governor of the Province of New York from 1664 to 1668.

Early life

Richard Nicolls was born in in Ampthill, Bedfordshire. He ...

captured the lightly defended New Amsterdam in 1664, and his subordinates quickly captured the remainder of New Netherland. The 1667 Treaty of Breda ended the Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War, began on 4 March 1665, and concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Breda (1667), Treaty of Breda on 31 July 1667. It was one in a series of Anglo-Dutch Wars, naval wars between Kingdom of England, England and the D ...

and confirmed English control of the region. The Dutch briefly regained control of parts of New Netherland in the Third Anglo-Dutch War

The Third Anglo-Dutch War, began on 27 March 1672, and concluded on 19 February 1674. A naval conflict between the Dutch Republic and England, in alliance with France, it is considered a related conflict of the wider 1672 to 1678 Franco-Dutch W ...

but surrendered claim to the territory in the 1674 Treaty of Westminster, ending the Dutch colonial presence in America.

The British renamed the colony of New Amsterdam to "York City" or "New York". Large numbers of Dutch remained in the colony, dominating the rural areas between Manhattan and Albany, while people from New England started moving in as well as immigrants from Germany. New York City attracted a large polyglot population, including a large black slave population. In 1674, the proprietary colonies of East Jersey

The Province of East Jersey, along with the Province of West Jersey, between 1674 and 1702 in accordance with the Quintipartite Deed, were two distinct political divisions of the Province of New Jersey, which became the U.S. state of New Jersey. ...

and West Jersey

West Jersey and East Jersey were two distinct parts of the Province of New Jersey. The political division existed for 28 years, between 1674 and 1702. Determination of an exact location for a border between West Jersey and East Jersey was often ...

were created from lands formerly part of New York.

Pennsylvania was founded in 1681 as a proprietary colony of Quaker William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer, religious thinker, and influential Quakers, Quaker who founded the Province of Pennsylvania during the British colonization of the Americas, British colonial era. An advocate of democracy and religi ...

. The main population elements included the Quaker population based in Philadelphia, a Scotch-Irish population on the Western frontier, and numerous German colonies in between. Philadelphia became the largest city in the colonies with its central location, excellent port, and a population of about 30,000.

New England

The Pilgrims were a small group ofPuritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

separatists who felt that they needed to distance themselves physically from the Church of England, which they perceived as corrupted. They initially moved to the Netherlands, but eventually sailed to America in 1620 on the ''Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English sailing ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, reac ...

''. Upon their arrival, they drew up the Mayflower Compact

The Mayflower Compact, originally titled Agreement Between the Settlers of New Plymouth, was the first governing document of Plymouth Colony. It was written by the men aboard the ''Mayflower,'' consisting of Separatist Puritans, adventurers, a ...

, by which they bound themselves together as a united community, thus establishing the small Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes spelled Plimouth) was the first permanent English colony in New England from 1620 and the third permanent English colony in America, after Newfoundland and the Jamestown Colony. It was settled by the passengers on t ...

. William Bradford was their main leader. After its founding, other settlers traveled from England to join the colony.

More Puritans immigrated in 1629 and established the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of M ...

with 400 settlers. They sought to reform the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

by creating a new, ideologically pure church in the New World. By 1640, 20,000 had arrived; many died soon after arrival, but the others found a healthy climate and an ample food supply. The Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies together spawned other Puritan colonies in New England, including the New Haven

New Haven is a city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound. With a population of 135,081 as determined by the 2020 U.S. census, New Haven is the third largest city in Co ...

, Saybrook, and Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

colonies. During the 17th century, the New Haven and Saybrook colonies were absorbed by Connecticut.

Roger Williams

Roger Williams (March 1683) was an English-born New England minister, theologian, author, and founder of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Pl ...

established Providence Plantations in 1636 on land provided by Narragansett sachem Canonicus. Williams was a Puritan who preached religious tolerance, separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

, and a complete break with the Church of England. He was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony over theological disagreements; he founded the settlement based on an egalitarian constitution, providing for majority rule "in civil things" and "liberty of conscience" in religious matters.

In 1637, a second group including Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (; July 1591 – August 1643) was an English-born religious figure who was an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her strong religious formal d ...

established a second settlement on Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

, today called Aquidneck. Samuel Gorton and others established a settlement near Providence Plantations which they called Shawomet. However, Massachusetts Bay attempted to seize the land and put it under their own authority, so Gorton travelled to London to gain a charter from the King. Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, praise, reno ...

assisted him in gaining the charter, so he changed the name of the settlement to Warwick. Roger Williams secured a Royal Charter from the King in 1663 which united all four settlements into the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was an English colony on the eastern coast of America, founded in 1636 by Puritan minister Roger Williams after his exile from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It became a haven for religious d ...

.

Other colonists settled to the north, mingling with adventurers and profit-oriented settlers to establish more religiously diverse colonies in New Hampshire

New Hampshire ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

and Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

. Massachusetts absorbed these small settlements when it made significant land claims in the 1640s and 1650s, but New Hampshire was eventually given a separate charter in 1679. Maine remained a part of Massachusetts until achieving statehood in 1820.

In 1685, King James II of England

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II of England, Charles II, on 6 February 1 ...

closed the legislatures and consolidated the New England colonies into the Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was a short-lived administrative union of English colonies covering all of New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies, with the exception of the Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvani ...

, putting the region under the control of Governor Edmund Andros. In 1688, the colonies of New York, West Jersey, and East Jersey were added to the dominion. Andros was overthrown and the dominion was closed in 1689, after the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

deposed King James II; the former colonies were re-established. According to Guy Miller, the Rebellion of 1689 was the "climax of the 60-year-old struggle between the government in England and the Puritans of Massachusetts over the question of who was to rule the Bay colony."

18th century

In 1702, East and West Jersey were combined to form theProvince of New Jersey

The Province of New Jersey was one of the Middle Colonies of Colonial history of the United States, Colonial America and became the U.S. state of New Jersey in 1776. The province had originally been settled by Europeans as part of New Netherla ...

.

The northern and southern sections of the Carolina colony operated more or less independently until 1691 when Philip Ludwell

Philip Cottington Ludwell ( 1638 – 1723) was an English-born planter and politician in colonial Virginia who sat on the Virginia Governor's Council, the first of three generations of men with the same name to do so, and briefly served as s ...

was appointed governor of the entire province. From that time until 1708, the northern and southern settlements remained under one government. However, during this period, the two halves of the province began increasingly to be known as North Carolina and South Carolina, as the descendants of the colony's proprietors fought over the direction of the colony. The colonists of Charles Town finally deposed their governor and elected their own government. This marked the start of separate governments in the Province of North-Carolina and the Province of South Carolina

The Province of South Carolina, originally known as Clarendon Province, was a province of the Kingdom of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the Thirteen Colonies i ...

. In 1729, the king formally revoked Carolina's colonial charter and established both North Carolina and South Carolina as crown colonies.

In the 1730s, Parliamentarian James Oglethorpe

Lieutenant-General James Edward Oglethorpe (22 December 1696 – 30 June 1785) was a British Army officer, Tory politician and colonial administrator best known for founding the Province of Georgia in British North America. As a social refo ...

proposed that the area south of the Carolinas be colonized with the "worthy poor" of England to provide an alternative to the overcrowded debtors' prisons. Oglethorpe and other English philanthropists secured a royal charter as the Trustees of the colony of Georgia on June 9, 1732. Oglethorpe and his compatriots hoped to establish a utopian colony that banned slavery and recruited only the most worthy settlers, but by 1750 the colony remained sparsely populated. The proprietors gave up their charter in 1752, at which point Georgia became a crown colony.

The population of the Thirteen Colonies grew immensely in the 18th century. According to historian Alan Taylor, the population was 1.5 million in 1750, which represented four-fifths of the population of British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

. More than 90 percent of the colonists lived as farmers, though some seaports also flourished. In 1760, the cities of Philadelphia, New York, and Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

had a population of more than 16,000, which was small by European standards. By 1770, the economic output of the Thirteen Colonies made up forty percent of the gross domestic product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the total market value of all the final goods and services produced and rendered in a specific time period by a country or countries. GDP is often used to measure the economic performanc ...

of the entire British Empire.

As the 18th century progressed, colonists began to settle far from the Atlantic coast. Pennsylvania, Virginia, Connecticut, and Maryland all laid claim to the land in the Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

valley. The colonies engaged in a scramble to purchase land from Indian tribes, as the British insisted that claims to land should rest on legitimate purchases. Virginia was particularly intent on western expansion, and most of the elite Virginia families invested in the Ohio Company

The Ohio Company, formally known as the Ohio Company of Virginia, was a land speculation company organized for the settlement by Virginians of the Ohio Country (approximately the present U.S. state of Ohio) and to trade with the Native Ameri ...

to promote the settlement of the Ohio Country

The Ohio Country (Ohio Territory, Ohio Valley) was a name used for a loosely defined region of colonial North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and south of Lake Erie.

Control of the territory and the region's fur trade was disputed i ...

.

Global trade and immigration

The British American colonies became part of the global British trading network, as the value tripled for exports from America to Britain between 1700 and 1754. The colonists were restricted in trading with other European powers, but they found profitable trade partners in the other British colonies, particularly in the Caribbean. The colonists traded foodstuffs, wood, tobacco, and various other resources for Asian tea, West Indian coffee, and West Indian sugar, among other items. American Indians far from the Atlantic coast supplied the Atlantic market with beaver fur and deerskins. America had an advantage in natural resources and established its own thriving shipbuilding industry, and many American merchants engaged in the transatlantic trade. Improved economic conditions and easing of religious persecution in Europe made it more difficult to recruit labor to the colonies, and many colonies became increasingly reliant on slave labor, particularly in the South. The population of slaves in America grew dramatically between 1680 and 1750, and the growth was driven by a mixture of forced immigration and the reproduction of slaves. Slaves supported vast plantation economies in the South, while slaves in the North worked in a variety of occupations. There were a few local attempted slave revolts, such as the Stono Rebellion and the New York Conspiracy of 1741, but these uprisings were suppressed. A small proportion of the English population migrated to America after 1700, but the colonies attracted new immigrants from other European countries. These immigrants traveled to all of the colonies, but the Middle Colonies attracted the most and continued to be more ethnically diverse than the other colonies. Numerous settlers immigrated from Ireland, both Catholic and Protestant—particularly " New Light"Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

. Protestant Germans also immigrated in large numbers, particularly to Pennsylvania. In the 1740s, the Thirteen Colonies underwent the First Great Awakening

The First Great Awakening, sometimes Great Awakening or the Evangelical Revival, was a series of Christian revivals that swept Britain and its thirteen North American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s. The revival movement permanently affected Pro ...

.

French and Indian War

In 1738, an incident involving a Welsh mariner named Robert Jenkins sparked the

In 1738, an incident involving a Welsh mariner named Robert Jenkins sparked the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear was fought by Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and History of Spain (1700–1808), Spain between 1739 and 1748. The majority of the fighting took place in Viceroyalty of New Granada, New Granada and the Caribbean ...

between Britain and Spain. Hundreds of North Americans volunteered for Admiral Edward Vernon

Admiral Edward Vernon (12 November 1684 – 30 October 1757) was a Royal Navy officer and politician. He had a long and distinguished career, rising to the rank of admiral after 46 years service. As a vice admiral during the War of Jenkins' E ...

's assault

In the terminology of law, an assault is the act of causing physical harm or consent, unwanted physical contact to another person, or, in some legal definitions, the threat or attempt to do so. It is both a crime and a tort and, therefore, may ...

on Cartagena de Indias

Cartagena ( ), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Region of Colombia, Caribbean Coast Region, along the Caribbean Sea. Cartagena's past ...

, a Spanish city in South America. The war against Spain merged into a broader conflict known as the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession was a European conflict fought between 1740 and 1748, primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italian Peninsula, Italy, the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Related conflicts include King Ge ...

, but most colonists called it King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in ...

. In 1745, British and colonial forces captured the town of Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The harbour had been used by European mariners since at least the 1590s, when it was known as English Port and Havre à l'An ...

, and the war came to an end with the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. However, many colonists were angered when Britain returned Louisbourg to France in return for Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

and other territories. In the aftermath of the war, both the British and French sought to expand into the Ohio River valley.

The French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

(1754–1763) was the American extension of the general European conflict known as the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

. Previous colonial wars in North America had started in Europe and then spread to the colonies, but the French and Indian War is notable for having started in North America and spread to Europe. One of the primary causes of the war was increasing competition between Britain and France, especially in the Great Lakes and Ohio valley.

The French and Indian War took on a new significance for the British North American colonists when William Pitt the Elder

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British Whig statesman who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him "Chatham" or "Pitt the Elder" to distinguish him from his son ...

decided that major military resources needed to be devoted to North America in order to win the war against France. For the first time, the continent became one of the main theaters of what could be termed a world war

A world war is an international War, conflict that involves most or all of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World War I ...

. During the war, it became increasingly apparent to American colonists that they were under the authority of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

, as British military and civilian officials took on an increased presence in their lives.

The war also increased a sense of American unity in other ways. It caused men to travel across the continent who might otherwise have never left their own colony, fighting alongside men from decidedly different backgrounds who were nonetheless still American. Throughout the course of the war, British officers trained Americans for battle, most notably George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, which benefited the American cause during the Revolution. Also, colonial legislatures and officials had to cooperate intensively in pursuit of the continent-wide military effort. The relations were not always positive between the British military establishment and the colonists, setting the stage for later distrust and dislike of British troops.

At the 1754 Albany Congress

The Albany Congress (June 19 – July 11, 1754), also known as the Albany Convention of 1754, was a meeting of representatives sent by the legislatures of seven of the British colonies in British America: Connecticut Colony, Connecticut, Prov ...

, Pennsylvania colonist Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

proposed the Albany Plan which would have created a unified government of the Thirteen Colonies for coordination of defense and other matters, but the plan was rejected by the leaders of most colonies.

In the Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Kingdom of France, France and Spanish Empire, Spain, with Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal in agree ...

, France formally ceded to Britain the eastern part of its vast North American empire, having secretly given to Spain the territory of Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

west of the Mississippi River the previous year. Before the war, Britain held the thirteen American colonies, most of present-day Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

, and most of the Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay, sometimes called Hudson's Bay (usually historically), is a large body of Saline water, saltwater in northeastern Canada with a surface area of . It is located north of Ontario, west of Quebec, northeast of Manitoba, and southeast o ...

watershed. Following the war, Britain gained all French territory east of the Mississippi River, including Quebec, the Great Lakes, and the Ohio River valley. Britain also gained Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida () was the first major European land-claim and attempted settlement-area in northern America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and th ...

, from which it formed the colonies of East

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

and West Florida

West Florida () was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. Great Britain established West and East Florida in 1763 out of land acquired from France and S ...

. In removing a major foreign threat to the thirteen colonies, the war also largely removed the colonists' need for colonial protection.

The British and colonists triumphed jointly over a common foe. The colonists' loyalty to the mother country was stronger than ever before. However, disunity was beginning to form. British Prime Minister William Pitt the Elder had decided to wage the war in the colonies with the use of troops from the colonies and tax funds from Britain itself. This was a successful wartime strategy but, after the war was over, each side believed that it had borne a greater burden than the other. The British elite, the most heavily taxed of any in Europe, pointed out angrily that the colonists paid little to the royal coffers. The colonists replied that their sons had fought and died in a war that served European interests more than their own. This dispute was a link in the chain of events that soon brought about the American Revolution.

Growing dissent

The British were left with large debts following the French and Indian War, so British leaders decided to increase taxation and control of the Thirteen Colonies. They imposed several new taxes, beginning with the Sugar Act 1764. Later acts included the Currency Act 1764, the Stamp Act 1765, and the Townshend Acts of 1767. Early American publishers and printers, Colonial newspapers and printers in particular took strong exception against the Stamp Act which imposed a tax on newspapers and official documents, and played a central role in disseminating literature among the colonists against such taxes and the idea of taxation without colonial representation. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 restricted settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, as this was designated an Indian Reserve (1763), Indian Reserve. Some groups of settlers disregarded the proclamation, however, and continued to move west and establish farms. The proclamation was modified and was no longer a hindrance to settlement, but the fact angered the colonists that it had been promulgated without their prior consultation.American Revolution

Parliament had directly levied duties and excise taxes on the colonies, bypassing the colonial legislatures, and Americans began to insist on the principle of " no taxation without representation" with intense protests over the Stamp Act of 1765. They argued that the colonies had no representation in the British Parliament, so it was a violation of their rights as Englishmen for taxes to be imposed upon them. Parliament rejected the colonial protests and asserted its authority by passing new taxes. Colonial discontentment grew with the passage of the 1773 Tea Act, which reduced taxes on tea sold by the East India Company in an effort to undercut the competition, and Prime Minister North's ministry hoped that this would establish a precedent of colonists accepting British taxation policies. Trouble escalated over the tea tax, as Americans in each colony boycotted the tea, and those in Boston dumped the tea in the harbor during the Boston Tea Party in 1773 when the Sons of Liberty dumped thousands of pounds of tea into the water. Tensions escalated in 1774 as Parliament passed the laws known as the Intolerable Acts, which greatly restricted self-government in the colony of Massachusetts. These laws also allowed British military commanders to claim colonial homes for the quartering of soldiers, regardless of whether the American civilians were willing or not to have soldiers in their homes. The laws further revoked colonial rights to hold trials in cases involving soldiers or crown officials, forcing such trials to be held in England rather than in America. Parliament also sent Thomas Gage to serve as Governor of Massachusetts and as the commander of British forces in North America. By 1774, colonists still hoped to remain part of the British Empire, but discontentment was widespread concerning British rule throughout the Thirteen Colonies. Colonists elected delegates to the First Continental Congress, which convened in Philadelphia in September 1774. In the aftermath of the Intolerable Acts, the delegates asserted that the colonies owed allegiance only to the king; they would accept royal governors as agents of the king, but they were no longer willing to recognize Parliament's right to pass legislation affecting the colonies. Most delegates opposed an attack on the British position in Boston, and the Continental Congress instead agreed to the imposition of a boycott known as the Continental Association. The boycott proved effective and the value of British imports dropped dramatically. The Thirteen Colonies became increasingly divided between Patriot (American Revolution), Patriots opposed to British rule and Loyalist (American Revolution), Loyalists who supported it.American Revolutionary War

Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

hosted a convention of delegates for the Thirteen Colonies. It raised an army to fight the British and named George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

its commander, made treaties, declared independence, and recommended that the colonies write constitutions and become states, later enumerated in the 1777 Articles of Confederation.

In May 1775, the Second Continental Congress, assembled in the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia, began recruiting soldiers for the Revolutionary War against the British, printing its own money, and appointing George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

as commander of Patriot militias. Those from New England that had launched the Siege of Boston, which forced British Army during the American Revolutionary War, British troops to withdraw from Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

. The patriot militias later were formalized into the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

under Washington's command.

Declaration of Independence

The Second Continental Congress charged the Committee of Five, including John Adams,Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

, Thomas Jefferson, Robert R. Livingston, and Roger Sherman, with authoring the United States Declaration of Independence, Declaration of Independence. The committee, in turn, asked Jefferson to author the first draft, which Jefferson largely wrote in isolation between June 11, 1776, and June 28, 1776, from the second floor of a three-story home he was renting at 700 Market Street (Philadelphia), Market Street in Philadelphia, now called the Declaration House and within walking distance of Independence Hall. Considering Congress's busy schedule, Jefferson probably had limited time for writing over these 17 days, and he likely wrote his first draft quickly.

On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress unanimously adopted and issued the Declaration as a letter of grievances to King George III;

With the help chiefly of France, they defeated the British in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. The decisive victory came at the Siege of Yorktown (1781), Siege of Yorktown in 1781. In the Treaty of Paris (1783), Britain officially recognized the independence of the United States of America.#mays2019, Mays 2019, p. 8#wallaceray2015, Wallace 2015, "American Revolution"

Population of Thirteen Colonies