õ¿š¥šÝ on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kim Il Sung (born Kim Song Ju; 15 April 1912 ã 8 July 1994) was a North Korean politician and the founder of North Korea, which he led as its first

Kim's family, part of the Jeonju Kim clan, is said to have originated in

Kim's family, part of the Jeonju Kim clan, is said to have originated in

The Soviet Union declared war on Japan on 8 August 1945, and the Red Army entered Pyongyang on 24 August 1945. Stalin had instructed

The Soviet Union declared war on Japan on 8 August 1945, and the Red Army entered Pyongyang on 24 August 1945. Stalin had instructed

In February 1946, Kim Il Sung decided to introduce a number of reforms. Over 50% of the

In February 1946, Kim Il Sung decided to introduce a number of reforms. Over 50% of the

Archival material suggestsWeathersby, Kathryn, "The Soviet Role in the Early Phase of the Korean War", ''The Journal of American-East Asian Relations'' 2, no. 4 (Winter 1993): 432Goncharov, Sergei N., Lewis, John W. and Xue Litai, ''Uncertain Partners: Stalin, Mao, and the Korean War'' (1993)Mansourov, Aleksandr Y., ''Stalin, Mao, Kim, and China's Decision to Enter the Korean War, 16 September ã 15 October 1950: New Evidence from the Russian Archives'', Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issues 6ã7 (Winter 1995/1996): 94ã107 that North Korea's decision to invade South Korea was Kim's initiative, not a Soviet one. Evidence suggests that

Archival material suggestsWeathersby, Kathryn, "The Soviet Role in the Early Phase of the Korean War", ''The Journal of American-East Asian Relations'' 2, no. 4 (Winter 1993): 432Goncharov, Sergei N., Lewis, John W. and Xue Litai, ''Uncertain Partners: Stalin, Mao, and the Korean War'' (1993)Mansourov, Aleksandr Y., ''Stalin, Mao, Kim, and China's Decision to Enter the Korean War, 16 September ã 15 October 1950: New Evidence from the Russian Archives'', Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issues 6ã7 (Winter 1995/1996): 94ã107 that North Korea's decision to invade South Korea was Kim's initiative, not a Soviet one. Evidence suggests that  On 25 October 1950, after sending various warnings of their intent to intervene if UN forces did not halt their advance,David Halberstam. Halberstam, David (25 September 2007). The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. Hyperion. Kindle Edition. Chinese troops in the thousands crossed the Yalu River and entered the war as allies of the KPA. There were nevertheless tensions between Kim and the Chinese government. Kim had been warned of the likelihood of an amphibious landing at Incheon, which was ignored. There was also a sense that the North Koreans had paid little in war compared to the Chinese who had fought for their country for decades against foes with better technology. The UN troops were forced to withdraw and Chinese troops retook Pyongyang in December and Seoul in January 1951. In March, UN forces began a new offensive, retaking Seoul and advanced north once again halting at a point just north of the 38th Parallel. After a series of offensives and counter-offensives by both sides, followed by a grueling period of largely static

On 25 October 1950, after sending various warnings of their intent to intervene if UN forces did not halt their advance,David Halberstam. Halberstam, David (25 September 2007). The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. Hyperion. Kindle Edition. Chinese troops in the thousands crossed the Yalu River and entered the war as allies of the KPA. There were nevertheless tensions between Kim and the Chinese government. Kim had been warned of the likelihood of an amphibious landing at Incheon, which was ignored. There was also a sense that the North Koreans had paid little in war compared to the Chinese who had fought for their country for decades against foes with better technology. The UN troops were forced to withdraw and Chinese troops retook Pyongyang in December and Seoul in January 1951. In March, UN forces began a new offensive, retaking Seoul and advanced north once again halting at a point just north of the 38th Parallel. After a series of offensives and counter-offensives by both sides, followed by a grueling period of largely static

13 April 2016.

As he aged, starting in the 1970s, Kim developed a

As he aged, starting in the 1970s, Kim developed a

Kim Il Sung is believed to have married 3 times, although virtually nothing is known about his first wife. His second wife, Kim Jong Suk (1917ã1949), gave birth to two sons and one daughter before her death in childbirth during the delivery of a stillborn girl. Kim Jong Il was his oldest son. The other son (

Kim Il Sung is believed to have married 3 times, although virtually nothing is known about his first wife. His second wife, Kim Jong Suk (1917ã1949), gave birth to two sons and one daughter before her death in childbirth during the delivery of a stillborn girl. Kim Jong Il was his oldest son. The other son (

Kim Il Sung was the author of many works. According to North Korean sources, these amount to approximately 10,800 speeches, reports, books, treatises, and others. Some, such as the 100-volume ''Complete Collection of Kim Il Sung's Works'' (), are published by the Workers' Party of Korea Publishing House. Shortly before his death, he published an eight-volume autobiography, ''

Kim Il Sung was the author of many works. According to North Korean sources, these amount to approximately 10,800 speeches, reports, books, treatises, and others. Some, such as the 100-volume ''Complete Collection of Kim Il Sung's Works'' (), are published by the Workers' Party of Korea Publishing House. Shortly before his death, he published an eight-volume autobiography, ''

online

NKIDP: Crisis and Confrontation on the Korean Peninsula: 1968ã1969, A Critical Oral History

* Oh, Kong Dan. ''Leadership Change in North Korean Politics: The Succession to Kim Il Sung'' (RAND, 1988

online

* Shen, Zhihua, and Yafeng Xia. ''A Misunderstood Friendship: Mao Zedong, Kim Il-sung, and Sino-North Korean Relations, 1949-1976'' (Revised Edition. Columbia University Press, 2020). * Szalontai, BalûÀzs, ''Kim Il Sung in the Khrushchev Era: SovietãDPRK Relations and the Roots of North Korean Despotism, 1953ã1964''. Stanford: Stanford University Press; Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press (2005)

online

Nicolae Ceausescu's visit to Pyongyang, North Korea, in 1971

"Conversations with Kim Il Sung"

at the Wilson Center Digital Archive

Kim Il Sung's works

at Publications of the DPRK {{DEFAULTSORT:Kim, Il-sung Kim Il Sung, 1912 births 1994 deaths 20th-century North Korean writers Anti-capitalists Anti-Japanese sentiment in North Korea Collars of the Order of the White Lion Former Presbyterians Generalissimos Grand Crosses of the National Order of Mali Grand Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland Heads of state of North Korea Juche Korean communists Korean expatriates in the Soviet Union Korean revolutionaries Socialist feminists Leaders of political parties in North Korea, Kim Il Sung Leaders of the Workers' Party of Korea and its predecessors Members of the Presidium of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 1st Central Committee of the Workers' Party of North Korea Members of the 2nd Central Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 1st Political Committee of the Workers' Party of North Korea Members of the 1st Standing Committee of the Workers' Party of North Korea Members of the 2nd Political Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 2nd Standing Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 3rd Standing Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 4th Political Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 5th Political Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 6th Politburo of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 6th Presidium of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 3rd Central Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 4th Central Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 5th Central Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 6th Central Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea Members of the 1st Supreme People's Assembly Members of the 2nd Supreme People's Assembly Members of the 3rd Supreme People's Assembly Members of the 4th Supreme People's Assembly Members of the 5th Supreme People's Assembly Members of the 6th Supreme People's Assembly Members of the 7th Supreme People's Assembly Members of the 8th Supreme People's Assembly Members of the 9th Supreme People's Assembly Heroes of the Republic (North Korea) Critics of religions North Korean atheists North Korean communists North Korean people of the Korean War North Korean people of the Vietnam War People from Pyongyang People of 88th Separate Rifle Brigade People of the Cold War Politicide perpetrators Prime ministers of North Korea Recipients of the Eduardo Mondlane Order Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of Polonia Restituta (1944ã1989) Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner Recipients of the Order of the Star of the Romanian Socialist Republic Soviet military personnel of World War II Stalinism Anti-American sentiment in North Korea Vice Chairmen of the Workers' Party of Korea and its predecessors Resistance members against Imperial Japan Anti-revisionists Korean resistance members Korean war criminals

supreme leader

A supreme leader or supreme ruler typically refers to powerful figures with an unchallenged authority, such as autocrats, dictators to spiritual and revolutionary leaders. Historic examples are Adolf Hitler () of Nazi Germany, Francisco ...

from its establishment in 1948 until his death in 1994. Afterwards, he was succeeded by his son Kim Jong Il

Kim Jong Il (born Yuri Kim; 16 February 1941 or 1942 ã 17 December 2011) was a North Korean politician who was the second Supreme Leader (North Korean title), supreme leader of North Korea from Death and state funeral of Kim Il Sung, the de ...

and was declared Eternal President.

He held the posts of the Premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of govern ...

from 1948 to 1972 and President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' PrûÎsident ...

from 1972 to 1994. He was the leader of the Workers' Party of Korea

The Workers' Party of Korea (WPK), also called the Korean Workers' Party (KWP), is the sole ruling party of North Korea. Founded in 1949 from a merger between the Workers' Party of North Korea and the Workers' Party of South Korea, the WPK is ...

(WPK) from 1949 to 1994 (titled as chairman from 1949 to 1966 and as general secretary after 1966). Coming to power after the end of Japanese rule over Korea in 1945 following Japan's surrender in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 ã 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he authorized the invasion of South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

in 1950, triggering an intervention in defense of South Korea by the United Nations led by the United States. Following the military stalemate in the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 ã 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, a ceasefire was signed in July 1953. He was the third-longest serving non-royal head of state/government in the 20th century, in office for more than 45 years.

Under his leadership, North Korea was established as a totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

personalist dictatorship

A dictatorship is an autocratic form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, who hold governmental powers with few to no limitations. Politics in a dictatorship are controlled by a dictator, and they are faci ...

with a centrally planned economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, ...

. It had very close political and economic relations with the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. By the 1960s, North Korea had a slightly higher standard of living

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available to an individual, community or society. A contributing factor to an individual's quality of life, standard of living is generally concerned with objective metrics outsid ...

than the South, which was suffering from political chaos and economic crises. The situation was reversed in the 1970s, as a newly stable South Korea became an economic powerhouse while North Korea's economy stagnated and then collapsed. Differences emerged between North Korea and the Soviet Union; chief among them was Kim Il Sung's philosophy of ''Juche

''Juche'', officially the ''Juche'' idea, is a component of Ideology of the Workers' Party of Korea#KimilsungismãKimjongilism, KimilsungismãKimjongilism, the state ideology of North Korea and the official ideology of the Workers' Party o ...

'', which focused on Korean nationalism

Korean nationalism can be viewed in two different contexts. One encompasses various movements throughout history to maintain a Korean cultural identity, history, and ethnicity (or "race"). This ethnic nationalism was mainly forged in opposition ...

and self-reliance

"Self-Reliance" is an 1841 essay written by American transcendentalist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson. It contains the most thorough statement of one of his recurrent themes: the need for each person to avoid conformity and false consistency, ...

. Despite this, the country received funds, subsidies and aid from the USSR and the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

until the dissolution of the USSR

Dissolution may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Dissolution'', a 2002 novel by Richard Lee Byers in the War of the Spider Queen series

* Dissolution (Sansom novel), ''Dissolution'' (Sansom novel), by C. J. Sansom, 2003

* Dissolution (Binge no ...

in 1991.

The resulting loss of economic aid negatively affected North Korea's economy, contributing to widespread famine in 1994. During this period, North Korea also remained critical of the United States defense force's presence in the region, which it considered imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

, having seized the American ship in 1968. This was part of an infiltration and subversion campaign to reunify the peninsula

A peninsula is a landform that extends from a mainland and is only connected to land on one side. Peninsulas exist on each continent. The largest peninsula in the world is the Arabian Peninsula.

Etymology

The word ''peninsula'' derives , . T ...

under North Korea's rule. Kim outlived his allies, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

and Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

, by over four and almost two decades, respectively, and remained in power during the terms of office of six South Korean Presidents and ten United States Presidents

The president of the United States is the head of state and head of government of the United States, indirectly elected to a four-year term via the Electoral College. Under the U.S. Constitution, the officeholder leads the executive branc ...

. Known as the Great Leader ('' Suryong''), he established a far-reaching personality cult which dominates domestic politics in North Korea. At the 6th WPK Congress in 1980, his oldest son Kim Jong Il

Kim Jong Il (born Yuri Kim; 16 February 1941 or 1942 ã 17 December 2011) was a North Korean politician who was the second Supreme Leader (North Korean title), supreme leader of North Korea from Death and state funeral of Kim Il Sung, the de ...

was elected to be a Presidium

A presidium or praesidium is a council of executive officers in some countries' political assemblies that collectively administers its business, either alongside an individual president or in place of one. The term is also sometimes used for the ...

member and chosen to be his successor, thus establishing the Kim dynasty.

Early life

Family background

Kim was born Kim Sung Ju to father Kim Hyong Jik and motherKang Pan Sok

Kang Pan Sok (; 21 April 1892 ã 31 July 1932) was the mother of North Korean leader Kim Il Sung, the paternal grandmother of Kim Jong Il, and a great grandmother of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

Biography

She came from the village ...

. Kim had two younger brothers, Kim Chol Ju and Kim Yong-ju

Kim Yong-ju (; 21 September 1920 ã 13 December 2021) was a North Korean politician and the younger brother of Kim Il Sung, who ruled North Korea from 1948 to 1994. Under his brother's rule, Kim Yong-ju held key posts including Politburo membe ...

. Kim Hyong Jik also had an adopted son Kim Ryong-ho, born in 1911. Kim Chol Ju died while fighting the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

and Kim Yong-ju came to be involved in the North Korean government; he was considered as an heir to his brother before he fell out of favor.

Kim's family, part of the Jeonju Kim clan, is said to have originated in

Kim's family, part of the Jeonju Kim clan, is said to have originated in Jeonju

Jeonju (, , ) is the capital and List of cities in South Korea, largest city of North Jeolla Province, South Korea. It is both urban and rural due to the closeness of Wanju County which almost entirely surrounds Jeonju (Wanju County has many resi ...

, North Jeolla Province

North Jeolla Province, officially Jeonbuk State (), is a Special Self-governing Province of South Korea in the Honam region in the southwest of the Korean Peninsula. Jeonbuk borders the provinces of South Chungcheong to the north, North Gyeo ...

. In 1860, his great-grandfather, Kim é˜ngu, settled in the Mangyongdae

Mangyongdae () is a neighborhood in Mangyongdae-guyok, Pyongyang, North Korea. North Korean propaganda claims Mangyongdae is the birthplace of North Korean leader Kim Il Sung, although in his memoirs

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narra ...

neighborhood of Pyongyang. Kim was reportedly born in the small village of Mangyungbong (then called Namni) near Pyongyang on 15 April 1912. According to a 1964 semi-official biography of Kim, he was born in his mother's home in Chingjong, and later grew up in Mangyungbong.

According to Kim, his family was always a step away from poverty. Kim said that he was raised by a very active Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

Christian family. His maternal grandfather was a Protestant minister, and his father had gone to a missionary school and he was also an elder in the Presbyterian Church. According to an official North Korean government account, Kim's family participated in anti-Japanese activities and fled to Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

in 1920. Like most Korean families, they resented the Japanese occupation of the Korean peninsula (which had begun on 29 August 1910). Japanese repression of Korean opposition was harsh, resulting in the arrest and detention of more than 52,000 Korean citizens in 1912 alone. This repression had forced many Korean families to flee the Korean peninsula, and settle in Manchuria.

Nevertheless, Kim's parents, especially his mother, played a role in the anti-Japanese struggle that was sweeping the peninsula. Their exact involvementwhether their cause was missionary, nationalist, or bothis unclear.

Communist and guerrilla activities

North Korean government sources credit Kim with founding theDown-with-Imperialism Union

The Down-with-Imperialism Union (DIU; ) was allegedly founded on 17 October 1926 in Hwatian County, Kirin, China, in order to fight against Japanese imperialism and to promote MarxismãLeninism. It is considered by the Workers' Party of Korea ...

in 1926. He attended Whasung Military Academy in 1926, but found the academy's training methods outdated and quit it in 1927. He then attended Yuwen Middle School in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

's Jilin province

)

, image_skyline = Changbaishan Tianchi from western rim.jpg

, image_alt =

, image_caption = View of Heaven Lake

, image_map = Jilin in China (+all claims hatched).svg

, mapsize = 275px

, map_a ...

until 1930, when he rejected the feudal traditions of older-generation Koreans and became interested in communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

ideologies. Seventeen-year-old Kim became the youngest member of the , an underground Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

organization with fewer than twenty members. It was led by Hé So (), who belonged to the . The police discovered the group three weeks after it formed in 1929, and jailed Kim for several months. Kim's formal education ended after his arrest and imprisonment.

In 1931, Kim joined the Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

(CCP)the Communist Party of Korea

The Communist Party of Korea () was a communist party in Korea founded during a secret meeting in Seoul in 1925. The Governor-General of Korea had banned communist and socialist parties under the Peace Preservation Law (see: history of Korea), s ...

had been founded in 1925, but had been thrown out of the Communist International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internationa ...

in the early 1930s for being too nationalist. He joined various anti-Japanese guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

groups in northern China. Feelings against the Japanese ran high in Manchuria, but as of May 1930 the Japanese had not yet occupied Manchuria. On 30 May 1930, a spontaneous violent uprising in eastern Manchuria arose in which peasants attacked some local villages in the name of resisting "Japanese aggression". The authorities easily suppressed this impromptu uprising. Because of the attack, the Japanese began to plan an occupation of Manchuria. In a speech Kim allegedly made before a meeting of Young Communist League delegates on 20 May 1931 in Yenchi County in Manchuria, he warned the delegates against such unplanned uprisings as the 30 May 1930 uprising in eastern Manchuria.

Four months later, on 18 September 1931, the " Mukden Incident" occurred, in which a relatively weak dynamite explosive charge went off near a Japanese railroad in the town of Mukden in Manchuria. Although no damage occurred, the Japanese used the incident as an excuse to send armed forces into Manchuria and to appoint a puppet government

A puppet state, puppet rûˋgime, puppet government or dummy government is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its ord ...

. In 1935, Kim became a member of the Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army

The Northeast Counter-Japanese United Army, also known as the NAJUA or Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army, was the main Counter-Japanese guerrilla army in Northeast China (Manchuria) after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Its prede ...

, a guerrilla group led by the CCP. Kim was appointed the same year to serve as political commissar for the 3rd detachment of the second division, consisting of around 160 soldiers. Here Kim met the man who would become his mentor as a communist, Wei Zhengmin, Kim's immediate superior officer, who at the time was chairman of the Political Committee of the Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army. Wei reported directly to Kang Sheng

Kang Sheng (; 4 November 1898 ã 16 December 1975), born Zhang Zongke (), was a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) official, politician and calligrapher best known for having overseen the work of the CCP's internal security and intelligence appara ...

, a high-ranking party member close to Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

in Yan'an

Yan'an; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi Province of China, province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several c ...

, until Wei's death on 8 March 1941.

Kim's actions during the Minsaengdan incident helped solidify his leadership. The CCP operating in Manchuria had become suspicious that any Korean in Manchuria could secretly be a member of the pro-Japanese Minsaengdan. A purge resulted: over 1,000 Koreans were expelled from the CCP, including Kim (who was arrested in late 1933 and exonerated in early 1934), and 500 were killed. Kim Il Sung's memoirsand those of the guerrillas who fought alongside himcite Kim's seizing and burning the suspect files of the Purge Committee as key to solidifying his leadership. After the destruction of the suspect files and the rehabilitation of suspects, those who had fled the purge rallied around Kim. As historian Suzy Kim summarizes, Kim Il Sung "emerged from the purge as a definitive leader, not only for the bold move but also for his compassion."

In 1935, Kim took the name ''Kim Il Sung'', meaning "Kim become the sun". Kim was appointed commander of the 6th division in 1937, at the age of 24, controlling a few hundred men in a group that came to be known as "Kim Il Sung's division". On 4 June 1937, he led 200 guerrillas in a raid on Poch'onbo, destroying the local government offices and setting fire to a Japanese police station and post office. The success of the raid demonstrated Kim's talents as a military leader. Even more significant than the military success itself was the political coordination and organization between the guerrillas and the Korean Fatherland Restoration Association, an anti-Japanese united front group based in Manchuria. These accomplishments would grant Kim some measure of fame among Chinese guerrillas, and North Korean biographies would later exploit it as a great victory for Korea.

For their part, the Japanese regarded Kim as one of the most effective and popular Korean guerrilla leaders ever. He appeared on Japanese wanted lists as the "Tiger". The Japanese "Maeda Unit" was sent to hunt him in February 1940. Later in 1940, the Japanese kidnapped a woman named Kim Hye-sun, believed to have been Kim Il Sung's first wife. After using her as a hostage to try to convince the Korean guerrillas to surrender, she was killed. Kim was appointed commander of the 2nd operational region for the 1st Army, but by the end of 1940 he was the only 1st Army leader still alive. Pursued by Japanese troops, in late 1940, Kim and a dozen of his fighters escaped by crossing the Amur River

The Amur River () or Heilong River ( zh, s=Õ£ÕƒÌÝ) is a perennial river in Northeast Asia, forming the natural border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China (historically the Outer and Inner Manchuria). The Amur ''proper'' is ...

into the Soviet Union. Kim was sent to a camp at Vyatskoye near Khabarovsk

Khabarovsk ( ) is the largest city and the administrative centre of Khabarovsk Krai, Russia,Law #109 located from the ChinaãRussia border, at the confluence of the Amur and Ussuri Rivers, about north of Vladivostok. As of the 2021 Russian c ...

, where the Soviets retrained the Korean communist guerrillas. In August 1942, Kim and his army were assigned to a special unit known as the 88th Separate Rifle Brigade

The 88th Separate Rifle Brigade (, , ), also known as the Northeast Anti-Japanese Allied Forces Teaching Brigade or the 88th International Brigade, was an international military unit of the Red Army created during World War II. It was unique in t ...

, which belonged to the Soviet Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of Peop ...

. Kim's immediate superior was Zhou Baozhong

Zhou Baozhong (; 1902ã1964) was a commander of the 88th Separate Rifle Brigade and Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army resisting the pacification of Manchukuo by the Empire of Japan.

After the Chinese Civil War he was made Vice Governor of Yu ...

. Kim became a Captain in the Soviet Red Army and served in it until the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 ã 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in 1945.

Claims that Kim Il Sung was an impostor

Several sources claim the name "Kim Il Sung" had previously been used by a prominent early leader of the Korean resistance, Kim Kyung-cheon. The Soviet officer Grigory Mekler, who worked with Kim during theSoviet occupation

During World War II, the Soviet Union occupied and annexed several countries effectively handed over by Nazi Germany in the secret MolotovãRibbentrop Pact of 1939. These included the eastern regions of Poland (incorporated into three differe ...

, said that Kim took this name from a former commander who had died. However, historian Andrei Lankov

Andrei Nikolaevich Lankov (; born 26 July 1963) is a Russian scholar of Asia and specialist in Korean studies and Director of Korea Risk Group, the parent company of NK News and NK Pro.

Early life and education

Lankov was born on 26 July 1963 ...

has argued that this is unlikely to be true. Several witnesses knew Kim before and after his time in the Soviet Union, including his superior, Zhou Baozhong

Zhou Baozhong (; 1902ã1964) was a commander of the 88th Separate Rifle Brigade and Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army resisting the pacification of Manchukuo by the Empire of Japan.

After the Chinese Civil War he was made Vice Governor of Yu ...

, who dismissed the claim of a "second" Kim in his diaries. Historian Bruce Cumings

Bruce Cumings (born September 5, 1943) is an American historian of East Asia, professor, lecturer and author. He is the Gustavus F. and Ann M. Swift Distinguished Service Professor in History, and the former chair of the history department at ...

pointed out that Japanese officers from the Kwantung Army

The Kwantung Army (Japanese language, Japanese: ÕÂÌÝÒ£, ''Kanté-gun'') was a Armies of the Imperial Japanese Army, general army of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1919 to 1945.

The Kwantung Army was formed in 1906 as a security force for th ...

have attested to his fame as a resistance figure.

On 12 August 2009, Yonhap News Agency

Yonhap News Agency (; ) is a major news agency in South Korea. It is based in Seoul, South Korea. Yonhap provides news articles, pictures, and other information to newspapers, TV networks and other media in South Korea.

History

Yonhap was esta ...

revealed that U.S. Army Military Government in Korea

The United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) was the official ruling body of the southern half of the Korean Peninsula from 9 September 1945 to 15 August 1948.

The country during this period was plagued with political and econ ...

had already acknowledged that Kim Il Sung was in fact pretended by his nephew Kim Song-ju. In 2019, investigative journalist Annie Jacobsen

Annie Jacobsen (born June 28, 1967) is an American investigative journalist, author, and a 2016 Pulitzer Prize finalist. She writes for and produces television programs, including ''Tom Clancy's Jack Ryan'' for Amazon Studios, and ''Clarice'' f ...

published the book ''Surprise, Kill, Vanish'', which further expounded that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

(CIA) once concluded that Kim Il Sung was a blackmail

Blackmail is a criminal act of coercion using a threat.

As a criminal offense, blackmail is defined in various ways in common law jurisdictions. In the United States, blackmail is generally defined as a crime of information, involving a thr ...

ed imposter operated by the Soviet Union. The dossier titled "The Identity of Kim Il Sung" ascribed the leader's true identity to Kim Song-ju, an orphaned child caught stealing money from a classmate who killed his classmate to avoid embarrassment. The dossier alleges Soviet intelligence officers identified the opportunity to blackmail Kim Song-ju into leading the North Korean Communist Party as a Soviet puppet under the name of the real war hero Kim-Il Sung, whom Stalin had disappeared. Jacobsen also writes that the CIA learned "specific instructions ere

Ere or ERE may refer to:

* ''Environmental and Resource Economics'', a peer-reviewed academic journal

* ERE Informatique, one of the first French video game companies

* Ere language, an Austronesian language

* Ebi Ere (born 1981), American-Nigeria ...

given to the leaders of the regime that there should be no questions raised about Kim l Sungs identity."

Historians generally accept the view that, while Kim's exploits were exaggerated by the personality cult

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristû°bal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an ideali ...

which was built around him, he was a significant guerrilla leader.

Leader of North Korea

Return to Korea

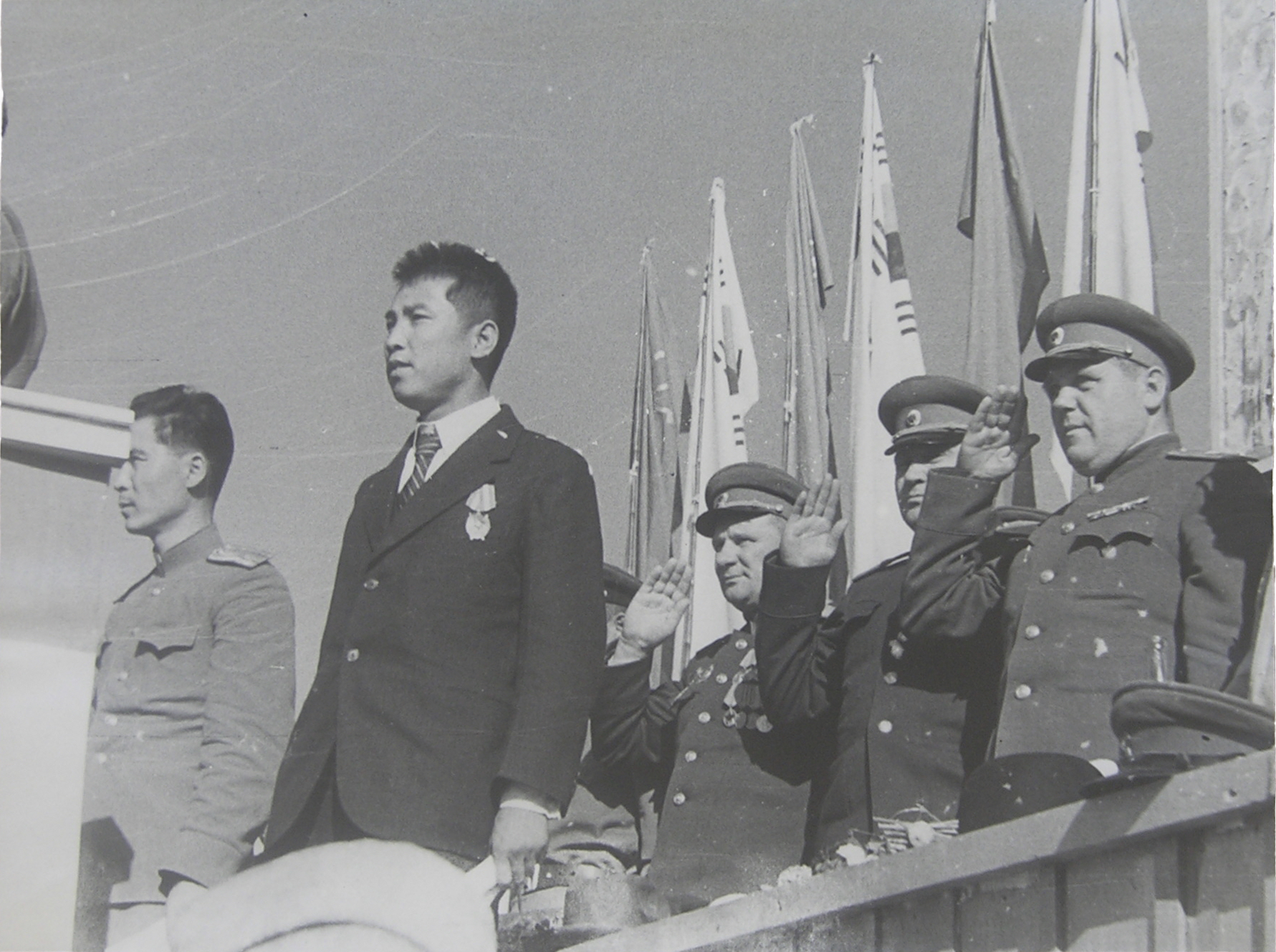

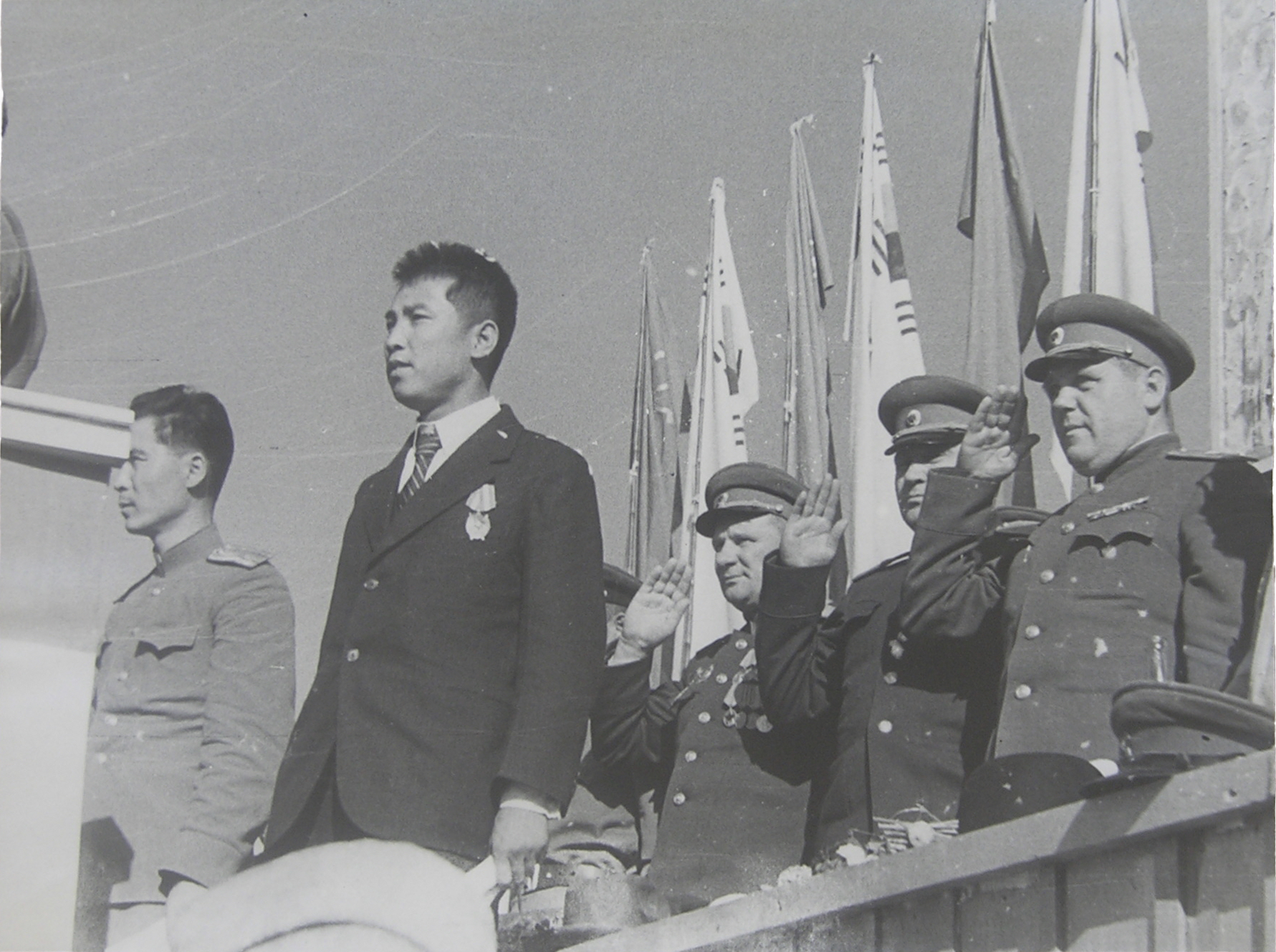

The Soviet Union declared war on Japan on 8 August 1945, and the Red Army entered Pyongyang on 24 August 1945. Stalin had instructed

The Soviet Union declared war on Japan on 8 August 1945, and the Red Army entered Pyongyang on 24 August 1945. Stalin had instructed Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria ka, ÃÃÃà ÃÃÃÂà ÃÃÃÃÃÃÀ èà ÃÃà ÃÃ} ''Lavrenti Pavles dze Beria'' ( ã 23 December 1953) was a Soviet politician and one of the longest-serving and most influential of Joseph ...

to recommend a communist leader for the Soviet-occupied territories and Beria met Kim several times before recommending him to Stalin.

Captain Kim Il Sung, a 33-year-old officer of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

, arrived at the Korean port of Wonsan

Wonsan (), previously known as Wonsanjin (), is a port city and naval base located in Kangwon Province (North Korea), Kangwon Province, North Korea, along the eastern side of the Korean Peninsula, on the Sea of Japan and the provincial capital. ...

on 19 September 1945 after 26 years in exile. According to Leonid Vassin, an officer with the Soviet MVD

The Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation (MVD; , ''Ministerstvo vnutrennikh del'') is the interior ministry of Russia.

The MVD is responsible for law enforcement in Russia through its agencies the Police of Russia, Migration ...

, Kim was essentially "created from zero". For one, his Korean was marginal at best; he only had eight years of formal education, all of it in Chinese. He needed considerable coaching to read a speech (which the MVD prepared for him) at a Communist Party congress three days after he arrived.

In December 1945, the Soviets installed Kim as first secretary of the North Korean Branch Bureau

The North Korean Branch Bureau (NKBB) of the Communist Party of Korea (CPK; ) was established by a CPK conference on 13 October 1945. It changed its name to the Communist Party of North Korea () on 10 April 1946 and became independent of the CP ...

of the Communist Party of Korea

The Communist Party of Korea () was a communist party in Korea founded during a secret meeting in Seoul in 1925. The Governor-General of Korea had banned communist and socialist parties under the Peace Preservation Law (see: history of Korea), s ...

. Originally, the Soviets preferred Cho Man-sik

Cho Man-sik (; 1 February 1883 ã possibly October 1950), also known by his art name Godang (), was a Korean independence activist.

He became involved in the power struggle that enveloped North Korea in the months following the Japanese su ...

to lead a popular front government, but Cho refused to support a Soviet-backed trusteeship and clashed with Kim. General Terentii Shtykov, who led the Soviet occupation of northern Korea, supported Kim over Pak Hon-yong

Pak Hon-yong (; 28 May 1900 ã 18 December 1955), courtesy name Togyong (), was a Korean independence activist, politician, philosopher, communist activist and one of the main leaders of the Communist Party of Korea, Korean communist movement ...

to lead the Provisional People's Committee for North Korea

The Provisional People's Committee of North Korea () was the provisional government of North Korea.

The committee was established on 8 February 1946 in response for the need of the Soviet Civil Administration and the communists to have centraliz ...

on 8 February 1946. As chairman of the committee, Kim was "the top Korean administrative leader in the North," though he was still ''de facto'' subordinate to General Shtykov until the Chinese intervention in the Korean War.

On 1 March 1946, while giving a speech to commemorate an anniversary of the March First Movement

The March First Movement was a series of protests against Korea under Japanese rule, Japanese colonial rule that was held throughout Korea and internationally by the Korean diaspora beginning on March 1, 1919. Protests were largely concentrated in ...

, a member of the anti-communist terrorist group the White Shirts Society attempted to assassinate Kim by lobbing a grenade at his podium. However, Soviet military officer Yakov Novichenko grabbed the grenade and absorbed the blast with his body, leaving Kim and other bystanders unharmed.

To solidify his control, Kim established the Korean People's Army

The Korean People's Army (KPA; ) encompasses the combined military forces of North Korea and the armed wing of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK). The KPA consists of five branches: the Korean People's Army Ground Force, Ground Force, the Ko ...

(KPA), aligned with the Communist Party, and he recruited a cadre of guerrillas and former soldiers who had gained combat experience in battles against the Japanese and later against Nationalist Chinese

The Nationalist government, officially the National Government of the Republic of China, refers to the government of the Republic of China from 1 July 1925 to 20 May 1948, led by the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) party.

Following the outbreak ...

troops. Using Soviet advisers and equipment, Kim constructed a large army skilled in infiltration tactics and guerrilla warfare. Prior to Kim's invasion of the South in 1950, which triggered the Korean War, Stalin equipped the KPA with modern, Soviet-built medium tanks, trucks, artillery, and small arms. Kim also formed an air force, equipped at first with Soviet-built propeller-driven fighters and attack aircraft. Later, North Korean pilot candidates were sent to the Soviet Union and China to train in MiG-15

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 (; USAF/DoD designation: Type 14; NATO reporting name: Fagot) is a jet fighter aircraft developed by Mikoyan-Gurevich for the Soviet Union. The MiG-15 was one of the first successful jet fighters to incorporate s ...

jet aircraft at secret bases.

Early years

AfterNorth Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

rejected the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

' plans to conduct nationwide elections in Korea, on 15 August 1948, the Republic of Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

, which claimed sovereignty over all of Korea, was established. In response, the Soviets held elections of their own in their northern occupation zone on 25 August 1948 for a Supreme People's Assembly

The Supreme People's Assembly (SPA; ) is the legislature of North Korea. It is ostensibly the highest organ of state power and the only branch of government in North Korea, with all state organs subservient to it under the principle of unified ...

. The Democratic People's Republic of Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

was proclaimed on 9 September 1948, with Kim as the Soviet-designated premier.

On 12 October, the Soviet Union recognized Kim's government as the sovereign government of the entire peninsula, including the south. The Communist Party merged with the New People's Party of Korea to form the Workers' Party of North Korea, with Kim as vice-chairman. In 1949, the Workers' Party of North Korea merged with its southern counterpart to become the Workers' Party of Korea

The Workers' Party of Korea (WPK), also called the Korean Workers' Party (KWP), is the sole ruling party of North Korea. Founded in 1949 from a merger between the Workers' Party of North Korea and the Workers' Party of South Korea, the WPK is ...

(WPK) with Kim as party chairman

In politics, a party chair (often party chairperson/-man/-woman or party president) is the presiding officer of a political party. The nature and importance of the position differs from country to country, and also between political parties.

Th ...

. By 1949, Kim and the communists had consolidated their rule in North Korea. Around this time, Kim began promoting an intense personality cult

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristû°bal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an ideali ...

. The first of many statues of him appeared, and he began calling himself "Great Leader".

In February 1946, Kim Il Sung decided to introduce a number of reforms. Over 50% of the

In February 1946, Kim Il Sung decided to introduce a number of reforms. Over 50% of the arable land

Arable land (from the , "able to be ploughed") is any land capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops.''Oxford English Dictionary'', "arable, ''adj''. and ''n.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. Alternatively, for the purposes of a ...

was redistributed, an 8-hour work day was proclaimed and all heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

was to be nationalized

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with priv ...

. There were improvements in the health of the population after he nationalized healthcare and made it available to all citizens.

Korean War

Archival material suggestsWeathersby, Kathryn, "The Soviet Role in the Early Phase of the Korean War", ''The Journal of American-East Asian Relations'' 2, no. 4 (Winter 1993): 432Goncharov, Sergei N., Lewis, John W. and Xue Litai, ''Uncertain Partners: Stalin, Mao, and the Korean War'' (1993)Mansourov, Aleksandr Y., ''Stalin, Mao, Kim, and China's Decision to Enter the Korean War, 16 September ã 15 October 1950: New Evidence from the Russian Archives'', Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issues 6ã7 (Winter 1995/1996): 94ã107 that North Korea's decision to invade South Korea was Kim's initiative, not a Soviet one. Evidence suggests that

Archival material suggestsWeathersby, Kathryn, "The Soviet Role in the Early Phase of the Korean War", ''The Journal of American-East Asian Relations'' 2, no. 4 (Winter 1993): 432Goncharov, Sergei N., Lewis, John W. and Xue Litai, ''Uncertain Partners: Stalin, Mao, and the Korean War'' (1993)Mansourov, Aleksandr Y., ''Stalin, Mao, Kim, and China's Decision to Enter the Korean War, 16 September ã 15 October 1950: New Evidence from the Russian Archives'', Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issues 6ã7 (Winter 1995/1996): 94ã107 that North Korea's decision to invade South Korea was Kim's initiative, not a Soviet one. Evidence suggests that Soviet intelligence

This is a list of historical secret police organizations. In most cases they are no longer current because the regime that ran them was overthrown or changed, or they changed their names. Few still exist under the same name as legitimate police fo ...

, through its espionage sources in the US government and British SIS

Sis or SIS may refer to:

People

*Michael Sis (born 1960), American Catholic bishop

Places

* Sis (ancient city), historical town in modern-day Turkey, served as the capital of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.

* Kozan, Adana, the current name ...

, had obtained information on the limitations of US atomic bomb stockpiles as well as defense program cuts, leading Stalin to conclude that the Truman administration would not intervene in Korea.

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

acquiesced only reluctantly to the idea of Korean reunification after being told by Kim that Stalin had approved the action. The Chinese did not provide North Korea with direct military support (other than logistics channels) until United Nations troops, largely US forces, had nearly reached the Yalu River

The Yalu River () or Amnok River () is a river on the border between China and North Korea. Together with the Tumen River to its east, and a small portion of Paektu Mountain, the Yalu forms the border between China and North Korea. Its valle ...

late in 1950. At the outset of the war in June and July, North Korean forces captured Seoul

Seoul, officially Seoul Special Metropolitan City, is the capital city, capital and largest city of South Korea. The broader Seoul Metropolitan Area, encompassing Seoul, Gyeonggi Province and Incheon, emerged as the world's List of cities b ...

and occupied most of the South, save for a small section of territory in the southeast region of the South that was called the Pusan Perimeter

The Battle of the Pusan Perimeter, known in Korean as the Battle of the Naktong River Defense Line (), was a large-scale battle between United Nations Command (UN) and North Korean forces lasting from August 4 to September 18, 1950. It was one ...

. But in September, the North Koreans were driven back by the US-led counterattack that started with the UN landing in Incheon

Incheon is a city located in northwestern South Korea, bordering Seoul and Gyeonggi Province to the east. Inhabited since the Neolithic, Incheon was home to just 4,700 people when it became an international port in 1883. As of February 2020, ...

, followed by a combined South Korean-US-UN offensive from the Pusan Perimeter. By October, UN forces had retaken Seoul and invaded the North to reunify the country under the South. On 19 October, US and South Korean troops captured Pyongyang, forcing Kim and his government to flee north, first to Sinuiju

SinéÙiju (; ) is a city in North Korea which faces Dandong, Liaoning, China, across the international border of the Yalu River. It is the capital of North Pyongan Province, North P'yéngan province. Part of the city is included in the Sinuiju Spe ...

and eventually into Kanggye

Kanggye (; ) is the provincial capital of Chagang, North Korea and has a population of 251,971. Because of its strategic importance, derived from its topography, it has been of military interest from the time of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910).

H ...

.

On 25 October 1950, after sending various warnings of their intent to intervene if UN forces did not halt their advance,David Halberstam. Halberstam, David (25 September 2007). The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. Hyperion. Kindle Edition. Chinese troops in the thousands crossed the Yalu River and entered the war as allies of the KPA. There were nevertheless tensions between Kim and the Chinese government. Kim had been warned of the likelihood of an amphibious landing at Incheon, which was ignored. There was also a sense that the North Koreans had paid little in war compared to the Chinese who had fought for their country for decades against foes with better technology. The UN troops were forced to withdraw and Chinese troops retook Pyongyang in December and Seoul in January 1951. In March, UN forces began a new offensive, retaking Seoul and advanced north once again halting at a point just north of the 38th Parallel. After a series of offensives and counter-offensives by both sides, followed by a grueling period of largely static

On 25 October 1950, after sending various warnings of their intent to intervene if UN forces did not halt their advance,David Halberstam. Halberstam, David (25 September 2007). The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. Hyperion. Kindle Edition. Chinese troops in the thousands crossed the Yalu River and entered the war as allies of the KPA. There were nevertheless tensions between Kim and the Chinese government. Kim had been warned of the likelihood of an amphibious landing at Incheon, which was ignored. There was also a sense that the North Koreans had paid little in war compared to the Chinese who had fought for their country for decades against foes with better technology. The UN troops were forced to withdraw and Chinese troops retook Pyongyang in December and Seoul in January 1951. In March, UN forces began a new offensive, retaking Seoul and advanced north once again halting at a point just north of the 38th Parallel. After a series of offensives and counter-offensives by both sides, followed by a grueling period of largely static trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising Trench#Military engineering, military trenches, in which combatants are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from a ...

that lasted from the summer of 1951 to July 1953, the front was stabilized along what eventually became the permanent " Armistice Line" of 27 July 1953. Over 2.5 million people died during the Korean War.

Chinese and Russian documents from that time reveal that Kim became increasingly desperate to establish a truce, since the likelihood that further fighting would successfully unify Korea under his rule became more remote with the UN and US presence. Kim also resented the Chinese taking over the majority of the fighting in his country, with Chinese forces stationed at the center of the front line, and the Korean People's Army being mostly restricted to the coastal flanks of the front.

Consolidation of power

With the end of the Korean War, despite the failure to unify Korea under his rule, Kim Il Sung proclaimed the war a victory in the sense that he had remained in power in the north. However, the three-year war left North Korea devastated, and Kim immediately embarked on a large reconstruction effort. He launched a five-year national economic plan (akin to Soviet Union's five-year plans) to establish acommand economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, ...

, with all industry owned by the state and all agriculture collectivized

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member-o ...

. The economy was focused on heavy industry and arms production. By the 1960s, North Korea enjoyed a standard of living which was higher than the standard of living in the South, which was fraught with political instability and economic crises.

In the ensuing years, Kim established himself as an independent leader of international communism

World communism, also known as global communism or international communism, is a form of communism placing emphasis on an international scope rather than being individual communist states. The long-term goal of world communism is an unlimited ...

. In 1956, he joined Mao in the " anti-revisionist" camp, which did not accept Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (ã 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

's program of de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

, yet he did not become a Maoist

Maoism, officially Mao Zedong Thought, is a variety of MarxismãLeninism that Mao Zedong developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China (1912ã1949), Republic o ...

himself. At the same time, he consolidated his power over the Korean communist movement. Rival leaders were eliminated. Pak Hon-yong

Pak Hon-yong (; 28 May 1900 ã 18 December 1955), courtesy name Togyong (), was a Korean independence activist, politician, philosopher, communist activist and one of the main leaders of the Communist Party of Korea, Korean communist movement ...

, leader of the Korean Communist Party, was purged and executed in 1955. Choe Chang-ik

Choe Chang-ik (, 1896ã1960) was a Korean politician in the Japanese colonial era. He was a member of the Korean independence movement. He was also known by the names Choe Chang-sok (), Choe Chang-sun (), Choe Tong-u (), and Ri Kon-u.

Early li ...

appears to have been purged as well. Yi Sang-Cho, North Korea's ambassador to the Soviet Union and a critic of Kim who defected to the Soviet Union in 1956, was declared a factionalist and a traitor. The 1955 ''Juche'' speech, which stressed Korean independence, debuted in the context of Kim's power struggle against leaders such as Pak, who had Soviet backing. This was little noticed at the time until state media started talking about it in 1963. Kim developed the policy and ideology of ''Juche

''Juche'', officially the ''Juche'' idea, is a component of Ideology of the Workers' Party of Korea#KimilsungismãKimjongilism, KimilsungismãKimjongilism, the state ideology of North Korea and the official ideology of the Workers' Party o ...

'' in opposition to the idea of North Korea as a satellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbiting a larger ob ...

of China or the Soviet Union.

Kim transformed North Korea into what Wonjun Song and Joseph Wright consider a personalist dictatorship, where power was centralized in Kim personally. Kim Il Sung's cult of personality

The North Korean cult of personality surrounding the Kim family has existed in North Korea for decades and can be found in many examples of North Korean culture. Although not acknowledged by the North Korean government, many defectors and Weste ...

had initially been criticized by some members of the government. The North Korean ambassador to the USSR, Li Sangjo, a member of the Yan'an faction

The Yan'an faction () were a group of pro-China communists in the North Korean government after the division of Korea following World War II.

The group was involved in a power struggle with pro-Soviet factions but Kim Il Sung was eventually able ...

, reported that it had become a criminal offense to so much as write on Kim's picture in a newspaper and that he had been elevated to the status of Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 ã 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, Mao, and Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

in the communist pantheon. He also charged Kim with rewriting history so it would appear as if his guerrilla faction had single-handedly liberated Korea from the Japanese, completely ignoring the assistance of the Chinese People's Volunteers

The People's Volunteer Army (PVA), officially the Chinese People's Volunteers (CPV), was the armed expeditionary forces deployed by the People's Republic of China during the Korean War. Although all units in the PVA were actually transferred ...

. In addition, Li stated that in the process of agricultural collectivization, grain was being forcibly confiscated from the peasants, leading to "at least 300 suicides" and he also stated that Kim made nearly all major policy decisions and appointments himself. Li reported that over 30,000 people were in prison for completely unjust and arbitrary reasons which were as trivial as not printing Kim Il Sung's portrait on sufficient quality paper or using newspapers with his picture to wrap parcels. Grain confiscation and tax collection were also conducted with force, which consisted of violence, beatings, and threats of imprisonment.

During the 1956 August faction incident, Kim Il Sung successfully resisted Soviet and Chinese efforts to depose him in favor of pro-Soviet Koreans or Koreans who belonged to the pro-Chinese Yan'an faction.Chung, Chin O. ''Pyongyang Between Peking and Moscow: North Korea's Involvement in the Sino-Soviet Dispute, 1958ã1975''. University of Alabama, 1978, p. 45. The last Chinese troops withdrew from the country in October 1958, which is the consensus as the latest date when North Korea became effectively independent, though some scholars believe that the 1956 August incident demonstrated North Korea's independence.

During his rise and his consolidation of power, Kim created the ''songbun

''Songbun'' (), formally chulsin-songbun (, from Sino-Korean ͤҤ¨, "origin" and ÌÍ, "constituent"), is the system of ascribed status used in North Korea. According to the U.S. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea and the American ...

'', a caste

A caste is a Essentialism, fixed social group into which an individual is born within a particular system of social stratification: a caste system. Within such a system, individuals are expected to marry exclusively within the same caste (en ...

system in which the North Korean people were divided into three groups. Each person was classified as belonging to the "core", "wavering", or "hostile" class, based on his or her political, social, and economic backgroundãthis caste system persists today. Songbun was used to decide all aspects of a person's existence in North Korean society, including access to education, housing, employment, food rationing, ability to join the ruling party, and even where a person was allowed to live. Large numbers of people from the so-called hostile class, which included intellectuals, land owners, and former supporters of Japan's occupying government during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 ã 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, were forcibly relocated to the country's isolated and impoverished northern provinces. When years of famine ravaged the country in the 1990s, those people who lived in its marginalized and remote communities were hardest hit.North Korea: Kim Il-Sung's Catastrophic Rights Legacy13 April 2016.

Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. Headquartered in New York City, the group investigates and reports on issues including War crime, war crimes, crim ...

, 2016.

During his rule, North Korea's government was responsible for widespread human rights abuses

Human rights are universally recognized moral principles or norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both national and international laws. These rights are considered inherent and inalienable, meaning t ...

. Kim Il Sung punished real and perceived dissent through purge

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertaking such an ...

s which included public execution

A public execution is a form of capital punishment which "members of the general public may voluntarily attend." This definition excludes the presence of only a small number of witnesses called upon to assure executive accountability. The purpose ...

s and enforced disappearances

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person with the support or acquiescence of a State (polity), state followed by a refusal to acknowledge the person's fate or whereabouts with the i ...

. Not only dissenters but their entire extended families were punished

''Punished'', also known as ''Bou ying'', is a 2011 Hong Kong thriller film directed by Law Wing-cheung. The film stars Anthony Wong, Richie Jen, and Janice Man.

Plot

The story starts with a real estate tycoon, Wong Ho-chiu (Anthony Wong), w ...

by being reduced to the lowest songbun rank, and many of them were also incarcerated in a secret system of political prison camps. These camps or '' kwanliso'', a part of Kim's vast network of abusive penal and forced labor institutions, were fenced and heavily guarded colonies which were located in mountainous areas of the country, where prisoners were forced to perform back-breaking labor such as logging, mining, and picking crops. Most of the prisoners were incarcerated in these camps for their entire lives, and inside the camps, their living and working conditions were usually deadly. For example, prisoners were nearly starved to death, they were denied medical care, they were denied proper housing and clothes, they were subjected to sexual violence, they were regularly mistreated, and they were torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

d and executed by guards.

Later years

Despite his opposition to de-Stalinization, Kim never officially severed relations with the Soviet Union, and he did not take part in theSino-Soviet split

The Sino-Soviet split was the gradual worsening of relations between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) during the Cold War. This was primarily caused by divergences that arose from their ...

. After Khrushchev was replaced by Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

in 1964, Kim's relations with the Soviet Union became closer. At the same time, Kim was increasingly alienated by Mao's unstable style of leadership, especially during the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a Social movement, sociopolitical movement in the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). It was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 and lasted until his de ...

in the late 1960s. Kim in turn was denounced by Mao's Red Guards

The Red Guards () were a mass, student-led, paramilitary social movement mobilized by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 until their abolition in 1968, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes

According to a ...

. At the same time, Kim reinstated relations with most of Eastern Europe's communist countries, primarily with Erich Honecker

Erich Ernst Paul Honecker (; 25 August 1912 ã 29 May 1994) was a German communist politician who led the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) from 1971 until shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. He held the post ...

's East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

and Nicolae Ceauàescu

Nicolae Ceauàescu ( ; ; ã 25 December 1989) was a Romanian politician who was the second and last Communism, communist leader of Socialist Romania, Romania, serving as the general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 u ...

's Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

. Ceauàescu was heavily influenced by Kim's ideology, and the personality cult

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristû°bal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an ideali ...

which grew around him in Romania was very similar to that of Kim.

In the 1960s, Kim became impressed with the efforts of North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; ; VNDCCH), was a country in Southeast Asia from 1945 to 1976, with sovereignty fully recognized in 1954 Geneva Conference, 1954. A member of the communist Eastern Bloc, it o ...

ese Leader Ho Chi Minh

(born ; 19 May 1890 ã 2 September 1969), colloquially known as Uncle Ho () among other aliases and sobriquets, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and politician who served as the founder and first President of Vietnam, president of the ...

to reunify Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

through guerrilla warfare and thought that something similar might be possible in Korea. Infiltration and subversion efforts were thus greatly stepped up against US forces and the leadership in South Korea. These efforts culminated in an attempt to storm the Blue House and assassinate President Park Chung Hee

Park Chung Hee (; ; November14, 1917October26, 1979) was a South Korean politician and army officer who served as the third president of South Korea from 1962 after he seized power in the May 16 coup of 1961 until Assassination of Park Chung ...

. North Korean troops thus took a much more aggressive stance toward US forces in and around South Korea, engaging US Army troops in fire-fights along the Demilitarized Zone. The 1968 capture of the crew of the spy ship USS ''Pueblo'' was a part of this campaign.

Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

's Enver Hoxha

Enver Halil Hoxha ( , ; ; 16 October 190811 April 1985) was an Albanian communist revolutionary and politician who was the leader of People's Socialist Republic of Albania, Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985. He was the Secretary (titl ...

(another independent-minded communist leader) was a fierce enemy of the country and Kim Il Sung, writing in June 1977 that "genuine Marxist-Leninists" will understand that the "ideology which is guiding the Korean Workers' Party and the Communist Party of China ... is revisionist" and later that month he added that "in Pyongyang, I believe that even Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, ÅŃîÅ¡Å¢ ÅîŃÅñ, ; 7 May 1892 ã 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito ( ; , ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and politician who served in various positions of national leadership from 1943 until his death ...

will be astonished at the proportions of the cult of his host im Il sung which has reached a level unheard of anywhere else, either in past or present times, let alone in a country which calls itself socialist." He further claimed that "the leadership of the Communist Party of China has betrayed he working people In Korea, too, we can say that the leadership of the Korean Workers' Party is wallowing in the same waters" and claimed that Kim Il Sung was begging for aid from other countries, especially among the Eastern Bloc and non-aligned countries like Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918ã19921941ã1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

. As a result, relations between North Korea and Albania would remain cold and tense right up until Hoxha's death in 1985.

Although a resolute anti-communist, Zaire

Zaire, officially the Republic of Zaire, was the name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1971 to 18 May 1997. Located in Central Africa, it was, by area, the third-largest country in Africa after Sudan and Algeria, and the 11th-la ...

's Mobutu Sese Seko

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa za Banga ( ; born Joseph-Dûˋsirûˋ Mobutu; 14 October 1930 ã 7 September 1997), often shortened to Mobutu Sese Seko or Mobutu and also known by his initials MSS, was a Congolese politician and military officer ...

was also heavily influenced by Kim's style of rule.

The North Korean government's practice of abducting foreign nationals, such as South Koreans

Demographic features of the population of South Korea include population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations, and other aspects of the population. The common language and especiall ...

, Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

, Chinese

Chinese may refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people identified with China, through nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**Han Chinese, East Asian ethnic group native to China.

**'' Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic ...

, Thais

Thais can be the plural of ''Thai'' and refer to:

* The Thai people, the main ethnic group of Thailand

* The Thai peoples or Tai peoples, the ethnic groups of southern China and Southeast Asia

In the singular, Thais may refer to:

People Ancien ...

, and Romanians

Romanians (, ; dated Endonym and exonym, exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group and nation native to Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Sharing a Culture of Romania, ...