–С–Њ—А–Њ–і–Є–љ –Р–ї–µ–Ї—Б–∞–љ–і—А –Я–Њ—А—Д–Є—А—М–µ–≤–Є—З on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

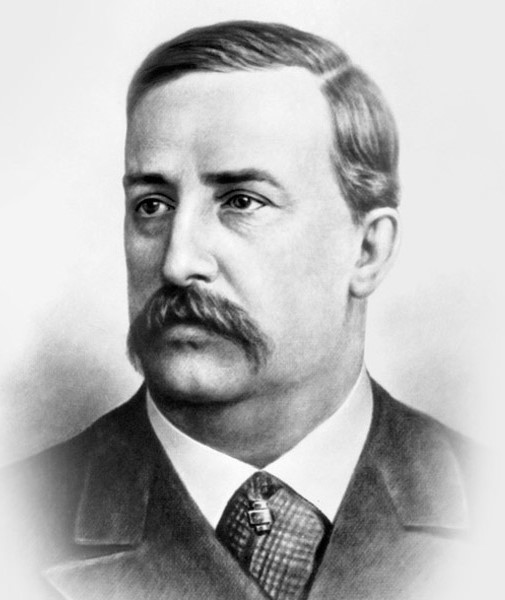

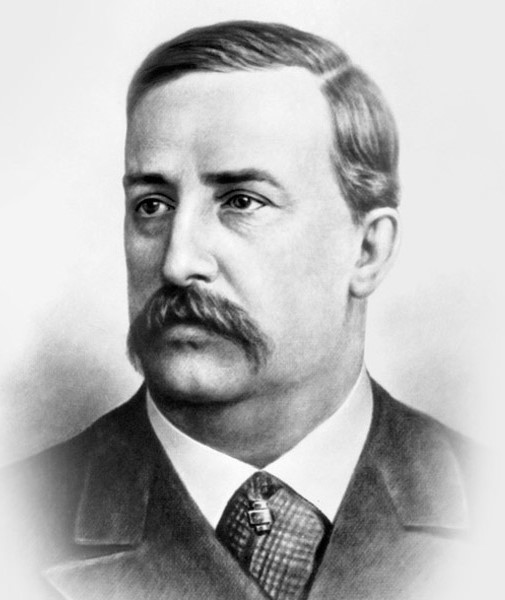

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin (12 November 183327 February 1887) was a Russian Romantic composer and

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin (12 November 183327 February 1887) was a Russian Romantic composer and

Borodin met

Borodin met

Borodin's tomb

{{DEFAULTSORT:Borodin, Alexander 1833 births 1887 deaths Burials at Tikhvin Cemetery Composers for piano 19th-century chemists 19th-century classical composers 19th-century male musicians Chemists from the Russian Empire Composers from the Russian Empire Male feminists Male opera composers Feminists from the Russian Empire Scientists from Saint Petersburg People from Sankt-Peterburgsky Uyezd Russian male classical composers Russian opera composers Russian Romantic composers Composers from Saint Petersburg Ballets Russes composers String quartet composers

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin (12 November 183327 February 1887) was a Russian Romantic composer and

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin (12 November 183327 February 1887) was a Russian Romantic composer and chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chƒУm(√≠a)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a graduated scientist trained in the study of chemistry, or an officially enrolled student in the field. Chemists study the composition of ...

of GeorgianвАУRussian parentage. He was one of the prominent 19th-century composers known as " The Five", a group dedicated to producing a "uniquely Russian" kind of classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be #Relationship to other music traditions, distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical mu ...

. Abraham, Gerald. ''Borodin: the Composer and his Music''. London, 1927. Borodin is known best for his symphonies, his two string quartet

The term string quartet refers to either a type of musical composition or a group of four people who play them. Many composers from the mid-18th century onwards wrote string quartets. The associated musical ensemble consists of two Violin, violini ...

s, the symphonic poem

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music, usually in a single continuous movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source. The German term ( ...

'' In the Steppes of Central Asia'' and his opera '' Prince Igor''.

A doctor

Doctor, Doctors, The Doctor or The Doctors may refer to:

Titles and occupations

* Physician, a medical practitioner

* Doctor (title), an academic title for the holder of a doctoral-level degree

** Doctorate

** List of doctoral degrees awarded b ...

and chemist by profession and training, Borodin made important early contributions to organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic matter, organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain ...

. Although he is presently known better as a composer, he regarded medicine and science as his primary occupations, only practising music and composition in his spare time or when he was ill. As a chemist, Borodin is known best for his work concerning organic synthesis

Organic synthesis is a branch of chemical synthesis concerned with the construction of organic compounds. Organic compounds are molecules consisting of combinations of covalently-linked hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen atoms. Within the gen ...

, including being among the first chemists to demonstrate nucleophilic substitution

In chemistry, a nucleophilic substitution (SN) is a class of chemical reactions in which an electron-rich chemical species (known as a nucleophile) replaces a functional group within another electron-deficient molecule (known as the electrophile) ...

, as well as being the co-discoverer of the aldol reaction

The aldol reaction (aldol addition) is a Chemical reaction, reaction in organic chemistry that combines two Carbonyl group, carbonyl compounds (e.g. aldehydes or ketones) to form a new ќ≤-hydroxy carbonyl compound. Its simplest form might invol ...

. Borodin was a promoter of education in Russia and founded the School of Medicine for Women in Saint Petersburg, where he taught until 1885.

In the 1880s pressures of work and ill health left him little time for composition. He died suddenly in 1887 while at a ball.

Life and profession

Family and personal life

Borodin was born inSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

as an illegitimate son of a 62-year-old Georgian nobleman, Luka Stepanovich Gedevanishvili, and a married 25-year-old Russian woman, Evdokia Konstantinovna Antonova. Due to the circumstances of Alexander's birth, the nobleman had him registered as the son of one of his Russian serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed dur ...

, Porfiry Borodin, hence the composer's Russian last name. As a result of this registration, both Alexander and his nominal Russian father Porfiry were officially serfs of Alexander's biological father Luka. The Georgian father emancipated Alexander from serfdom when he was 7 years old and provided housing and money for him and his mother. Despite this, Alexander was never publicly recognized by his mother, who was referred to by young Borodin as his "aunt".Lewis, David E. ''Early Russian Organic Chemists and Their Legacy.'' Springer Science & Business Media

Springer Science+Business Media, commonly known as Springer, is a German multinational publishing company of books, e-books and peer-reviewed journals in science, humanities, technical and medical (STM) publishing.

Originally founded in 1842 in ...

, 3 April 2012, p. 61

Despite his status as a commoner, Borodin was well provided for by his Georgian father and grew up in a large four-storey house, which was gifted to Alexander and his "aunt" by the nobleman. Although his registration prevented enrollment in a proper gymnasium, Borodin received good education in all of the subjects through private tutors at home. During 1850 he enrolled in the MedicalвАУSurgical Academy in Saint Petersburg, which was later the workplace of Ivan Pavlov

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (, ; 27 February 1936) was a Russian and Soviet experimental neurologist and physiologist known for his discovery of classical conditioning through his experiments with dogs. Pavlov also conducted significant research on ...

, and pursued a career in chemistry. On graduation he spent a year as surgeon in a military hospital, followed by three years of advanced scientific study in western Europe.

During 1862, Borodin returned to Saint Petersburg to begin a professorship of chemistry at the Imperial Medical-Surgical Academy and spent the remainder of his scientific career in research, lecturing and overseeing the education of others. Eventually, he established medical courses for women in 1872.

He began taking lessons in composition from Mily Balakirev

Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev ( , ; ,BGN/PCGN romanization of Russian, BGN/PCGN romanization: ; ALA-LC romanization of Russian, ALA-LC system: ; ISO 9, ISO 9 system: . ; вАУ )Russia was still using Adoption of the Gregorian calendar#Adoption in E ...

during 1862. He married Ekaterina Protopopova, a pianist, during 1863, with whom he adopted several daughters. Music remained a secondary vocation for Borodin besides his main career as a chemist and physician. He suffered poor health, having overcome cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

and several minor heart failures. He died suddenly during a ball at the academy, and was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg.

Career as a chemist

In his profession Borodin gained great respect, being particularly noted for his work onaldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

s. Between 1859 and 1862 Borodin had a postdoctoral position at Heidelberg University

Heidelberg University, officially the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg (; ), is a public research university in Heidelberg, Baden-W√Љrttemberg, Germany. Founded in 1386 on instruction of Pope Urban VI, Heidelberg is Germany's oldest unive ...

. He worked in the laboratory of Emil Erlenmeyer

Richard August Carl Emil Erlenmeyer (28 June 1825 вАУ 22 January 1909), known simply as Emil Erlenmeyer, was a German chemist known for contributing to the early development of the theory of chemical structure and formulating the Erlenmeyer rul ...

working on benzene derivatives. He also spent time in Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

, working on halocarbon

Halocarbon compounds are chemical compounds in which one or more carbon atoms are linked by covalent bonds with one or more halogen atoms (fluorine, chlorine, bromine or iodine вАУ ) resulting in the formation of organofluorine compounds, or ...

s. One experiment published during 1862 described the first nucleophilic displacement of chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between ...

by fluorine

Fluorine is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol F and atomic number 9. It is the lightest halogen and exists at Standard temperature and pressure, standard conditions as pale yellow Diatomic molecule, diatomic gas. Fluorine is extre ...

in benzoyl chloride. The radical halodecarboxylation of aliphatic carboxylic acids was first demonstrated by Borodin during 1861 by his synthesis of methyl bromide

Bromomethane, commonly known as methyl bromide, is an organobromine compound with chemical formula, formula Carbon, CHydrogen, H3Bromine, Br. This colorless, odorless, nonflammable gas is Bromine cycle, produced both industrially and biologically ...

from silver acetate. It was Heinz Hunsdiecker and his wife Cläre, however, who developed Borodin's work into a general method, for which they were granted a US patent

Under United States law, a patent is a right granted to the inventor of a (1) process, machine, article of manufacture, or composition of matter, (2) that is new, useful, and non-obvious. A patent is the right to exclude others, for a limit ...

during 1939, and which they published in the journal ''Chemische Berichte

''Chemische Berichte'' (usually abbreviated as ''Ber.'' or ''Chem. Ber.'') was a German-language scientific journal of all disciplines of chemistry founded in 1868. It was one of the oldest scientific journals in chemistry, until it merged with ' ...

'' during 1942. The method is generally known as either the Hunsdiecker reaction or the Hunsdiecker–Borodin reaction.

During 1862, Borodin returned to the MedicalвАУSurgical Academy (now known as the S. M. Kirov Military Medical Academy), and accepted a professorship of chemistry. He worked on self-condensation

Condensation is the change of the state of matter from the gas phase into the liquid phase, and is the reverse of vaporization. The word most often refers to the water cycle. It can also be defined as the change in the state of water vapor ...

of small aldehydes in a process now known as the aldol reaction

The aldol reaction (aldol addition) is a Chemical reaction, reaction in organic chemistry that combines two Carbonyl group, carbonyl compounds (e.g. aldehydes or ketones) to form a new ќ≤-hydroxy carbonyl compound. Its simplest form might invol ...

, the discovery of which is jointly credited to Borodin and Charles Adolphe Wurtz. Borodin investigated the condensation of valerian aldehyde and oenanth aldehyde, which was reported by von Richter during 1869. During 1873, he described his work to the Russian Chemical Society and noted similarities with compounds recently reported by Wurtz.

He published his last full article during 1875 on reactions of amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a chemical compound, compound with the general formula , where R, R', and RвА≥ represent any group, typically organyl functional group, groups or hydrogen at ...

s and his last publication concerned a method for the identification of urea

Urea, also called carbamide (because it is a diamide of carbonic acid), is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two Amine, amino groups (вАУ) joined by a carbonyl functional group (вАУC(=O)вАУ). It is thus the simplest am ...

in animal urine.

His successor as chemistry professor of the Medical-Surgical academy was his son-in-law and fellow chemist, Aleksandr Dianin

Aleksandr Pavlovich Dianin (; 20 April 1851 вАУ 6 December 1918) was a Russians, Russian chemist from Saint Petersburg. He carried out studies on phenols and discovered a phenol derivative (chemistry), derivative now known as bisphenol A and the ...

.

Musical avocation

Opera and orchestral works

Borodin met

Borodin met Mily Balakirev

Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev ( , ; ,BGN/PCGN romanization of Russian, BGN/PCGN romanization: ; ALA-LC romanization of Russian, ALA-LC system: ; ISO 9, ISO 9 system: . ; вАУ )Russia was still using Adoption of the Gregorian calendar#Adoption in E ...

during 1862. While under Balakirev's tutelage in composition he began his Symphony No. 1 in E-flat major; it was first performed during 1869, with Balakirev conducting. During that same year Borodin started on his Symphony No. 2 in B minor, which was not particularly successful at its premiere during 1877 under Eduard Nápravník, but with some minor re-orchestration received a successful performance during 1879 by the Free Music School under Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov. At the time, his name was spelled , which he romanized as Nicolas Rimsky-Korsakow; the BGN/PCGN transliteration of Russian is used for his name here; ALA-LC system: , ISO 9 system: .. (18 March 1844 вАУ 2 ...

's direction. During 1880 he composed the popular symphonic poem

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music, usually in a single continuous movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source. The German term ( ...

'' In the Steppes of Central Asia''. Two years later he began composing a third symphony, but left it unfinished at his death; two movements of it were later completed and orchestrated by Alexander Glazunov

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov ( вАУ 21 March 1936) was a Russian composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Russian Romantic period. He was director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 and 1928 and was instrumental i ...

.

During 1868, Borodin became distracted from initial work on the second symphony by preoccupation with the opera

Opera is a form of History of theatre#European theatre, Western theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by Singing, singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically ...

'' Prince Igor'', which is considered by some to be his most significant work and one of the most important historical Russian operas. It contains the '' Polovtsian Dances'', often performed as a stand-alone concert work forming what is probably Borodin's best-known composition. Borodin left the opera (and a few other works) incomplete at his death.

'' Prince Igor'' was completed posthumously by Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov ( вАУ 21 March 1936) was a Russian composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Russian Romantic period. He was director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 and 1928 and was instrumental i ...

. It is set in the 12th century, when the Russians, commanded by Prince Igor of Seversk, determined to conquer the barbarous Polovtsians by travelling eastward across the Steppes. The Polovtsians were apparently a nomadic tribe originally of Turkic origin who habitually attacked southern Russia. A full solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs approximately every six months, during the eclipse season i ...

early during the first act foreshadows an ominous outcome to the invasion. Prince Igor's troops are defeated. The story tells of the capture of Prince Igor, and his son, Vladimir, of Russia by Polovtsian chief Khan Konchak, who entertains his prisoners lavishly and orders his slaves to perform the famous 'Polovtsian Dances', which provide a thrilling climax to the second act. The second half of the opera finds Prince Igor returning to his homeland, but rather than finding himself in disgrace, he is welcomed home by the townspeople and by his wife, Yaroslavna. Although for a while rarely performed in its entirety outside of Russia, this opera has received two notable new productions recently, one at the Bolshoi State Opera and Ballet Company in Russia during 2013, and one at the Metropolitan Opera Company of New York City during 2014.

Chamber music

No other member of the Balakirev circle identified himself so much withabsolute music

Absolute music (sometimes abstract music) is music that is not explicitly "about" anything; in contrast to program music, it is non- representational.M. C. Horowitz (ed.), ''New Dictionary of the History of Ideas'', , Vol. 1, p. 5 The idea of ab ...

as did Borodin in his two string quartets, in addition to his many earlier chamber compositions. As a cellist, he was an enthusiastic chamber music player, an interest that increased during his chemical studies in Heidelberg between 1859 and 1861. This early period yielded, among other chamber works, a string sextet and a piano quintet. Borodin based the thematic structure and instrumental texture of his pieces on those of Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic music, Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions inc ...

.

During 1875 Borodin started his First String Quartet, much to the displeasure of Mussorgsky and Vladimir Stasov; the other members of The Five were known to be hostile to chamber music. The First Quartet demonstrates mastery of the string quartet form. Borodin's Second Quartet, written in 1881, displays strong lyricism, as in the third movement's popular " Nocturne." While the First Quartet is richer in changes of mood, the Second Quartet has a more uniform atmosphere and expression.

Musical legacy

Borodin's fame outside theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

was made possible during his lifetime by Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt (22 October 1811 вАУ 31 July 1886) was a Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor and teacher of the Romantic music, Romantic period. With a diverse List of compositions by Franz Liszt, body of work spanning more than six ...

, who arranged a performance of the Symphony No. 1 in Germany during 1880, and by the Comtesse de Mercy-Argenteau in Belgium and France. His music is noted for its strong lyricism and rich harmonies. Along with some influences from Western composers, as a member of The Five, his music is also characteristic of the Russian style. His passionate music and unusual harmonies proved to have a lasting influence on the younger French composers Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 вАУ 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

and Ravel (in homage, the latter composed during 1913 a piano piece entitled "√А la mani√®re de Borodine").

The evocative characteristics of Borodin's musicвАФspecifically ''In the Steppes of Central Asia'', his Symphony No. 2, ''Prince Igor'' вАУ made possible the adaptation of his compositions in the 1953 musical

Musical is the adjective of music.

Musical may also refer to:

* Musical theatre, a performance art that combines songs, spoken dialogue, acting and dance

* Musical film

Musical film is a film genre in which songs by the Character (arts), charac ...

'' Kismet'', by Robert Wright and George Forrest, notably in the songs " Stranger in Paradise", " And This Is My Beloved" and " Baubles, Bangles, & Beads". In 1954, Borodin was posthumously awarded a Tony Award

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as a Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual ce ...

for this show.

Subsequent references

*The Borodin Quartet was named in his honour. *The chemistAlexander Shulgin

Alexander Theodore "Sasha" Shulgin (June 17, 1925 вАУ June 2, 2014) was an American biochemist, broad researcher of synthetic psychoactive compounds, and author of works regarding these, who independently explored the organic chemistry and ph ...

uses the name "Alexander Borodin" as a fictional persona in the books ''PiHKAL

''PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story'' is a book by Alexander Shulgin and Ann Shulgin published in 1991. The subject of the work is Psychoactive drug, psychoactive phenethylamine Derivative (chemistry), chemical derivatives, notably those that act ...

'' and '' TiHKAL''.

*In his book ''Burning in Water, Drowning in Flame'' (1974) Charles Bukowski

Henry Charles Bukowski ( ; born Heinrich Karl Bukowski, ; August 16, 1920 вАУ March 9, 1994) was a German Americans, German-American poet, novelist, and short story writer. His writing was influenced by the social, cultural, and economic ambien ...

wrote a poem about the composer entitled "The Life of Borodin".

*The asteroid previously known by its provisional designation 1990 ES3 was assigned the permanent name (6780) Borodin, in honor of Alexander Borodin. (6780) Borodin is a main-belt asteroid with an estimated diameter of 4 km and an orbital period of 3.37 years.

*The score of the 1953 musical '' Kismet'' and the subsequent '' film version'' was based extensively on compositions by Borodin, such as the second string quartet, second symphony and piano works.

*On 12 November 2018, Google

Google LLC (, ) is an American multinational corporation and technology company focusing on online advertising, search engine technology, cloud computing, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, consumer electronics, and artificial ...

recognized him with a doodle

A doodle is a drawing made while a person's attention is otherwise occupied. Doodles are simple drawings that can have concrete representational meaning or may just be composed of random and abstract art, abstract lines or shapes, generally w ...

.

Notes

References

Sources * *Further reading

* * * * Willem G. Vijvers, ''Alexander Borodin; Composer, Scientist, Educator'' (Amsterdam: The American Book Center, 2013). .External links

* * * *, in the film '' Moscow Clad in Snow''Borodin's tomb

{{DEFAULTSORT:Borodin, Alexander 1833 births 1887 deaths Burials at Tikhvin Cemetery Composers for piano 19th-century chemists 19th-century classical composers 19th-century male musicians Chemists from the Russian Empire Composers from the Russian Empire Male feminists Male opera composers Feminists from the Russian Empire Scientists from Saint Petersburg People from Sankt-Peterburgsky Uyezd Russian male classical composers Russian opera composers Russian Romantic composers Composers from Saint Petersburg Ballets Russes composers String quartet composers