|

Mindâbody Dualism

In the philosophy of mind, mindâbody dualism denotes either that mental phenomena are non-physical, Hart, W. D. 1996. "Dualism." pp. 265â267 in ''A Companion to the Philosophy of Mind'', edited by S. Guttenplan. Oxford: Blackwell. or that the mind and body are distinct and separable. Thus, it encompasses a set of views about the relationship between mind and matter, as well as between subject and object, and is contrasted with other positions, such as physicalism and enactivism, in the mindâbody problem. Aristotle shared Plato's view of multiple souls and further elaborated a hierarchical arrangement, corresponding to the distinctive functions of plants, animals, and humans: a nutritive soul of growth and metabolism that all three share; a perceptive soul of pain, pleasure, and desire that only humans and other animals share; and the faculty of reason that is unique to humans only. In this view, a soul is the hylomorphic form of a viable organism, wherein each ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Substance Theory

Substance theory, or substanceâattribute theory, is an ontological theory positing that objects are constituted each by a ''substance'' and properties borne by the substance but distinct from it. In this role, a substance can be referred to as a ''substratum'' or a '' thing-in-itself''. ''Substances'' are particulars that are ontologically independent: they are able to exist all by themselves. Another defining feature often attributed to substances is their ability to ''undergo changes''. Changes involve something existing ''before'', ''during'' and ''after'' the change. They can be described in terms of a persisting substance gaining or losing properties. ''Attributes'' or ''properties'', on the other hand, are entities that can be exemplified by substances. Properties characterize their bearers; they express what their bearer is like. ''Substance'' is a key concept in ontology, the latter in turn part of metaphysics, which may be classified into monist, dualist, or plural ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

René Descartes

RenĂ© Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 â 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramount to his method of inquiry, and he connected the previously separate fields of geometry and algebra into analytic geometry. Descartes spent much of his working life in the Dutch Republic, initially serving the Dutch States Army, and later becoming a central intellectual of the Dutch Golden Age. Although he served a Dutch Reformed Church, Protestant state and was later counted as a Deism, deist by critics, Descartes was Roman Catholicism, Roman Catholic. Many elements of Descartes's philosophy have precedents in late Aristotelianism, the Neostoicism, revived Stoicism of the 16th century, or in earlier philosophers like Augustine of Hippo, Augustine. In his natural philosophy, he differed from the Scholasticism, schools on two major point ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Politicus

The ''Statesman'' (, ''Politikós''; Latin: ''Politicus''), also known by its Latin title, ''Politicus'', is a Socratic dialogue written by Plato. The text depicts a conversation among Socrates, the mathematician Theodorus, another person named Socrates (referred to as "Socrates the Younger"), and an unnamed philosopher from Elea referred to as "the Stranger" (, ''xénos''). It is ostensibly an attempt to arrive at a definition of "statesman," as opposed to "sophist" or "philosopher" and is presented as following the action of the ''Sophist''. The ''Sophist'' had begun with the question of whether the sophist, statesman, and philosopher were one or three, leading the Eleatic Stranger to argue that they were three but that this could only be ascertained through full accounts of each (''Sophist'' 217b). But though Plato has his characters give accounts of the sophist and statesman in their respective dialogues, it is most likely that he never wrote a dialogue about the philos ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sophist (dialogue)

The ''Sophist'' (; Henri Estienne (ed.), ''Platonis opera quae extant omnia'', Vol. 1, 1578p. 217) is a Platonic dialogue from the philosopher's late period, most likely written in 360 BC. In it the interlocutors, led by Eleatic Stranger employ the method of division in order to classify and define the sophist and describe his essential attributes and differentia vis a vis the philosopher and statesman. Like its sequel, the '' Statesman'', the dialogue is unusual in that Socrates is present but plays only a minor role. Instead, the Eleatic Stranger takes the lead in the discussion. Because Socrates is silent, it is difficult to attribute the views put forward by the Eleatic Stranger to Plato, beyond the difficulty inherent in taking any character to be an author's "mouthpiece". Background The main objective of the dialogue is to identify what a sophist is and how a sophist differs from a philosopher and statesman. Because each seems distinguished by a particular form of knowl ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Theaetetus (dialogue)

The ''Theaetetus'' (; ''TheaĂtÄtos'', Latinisation of names, lat. ''Theaetetus'') is a philosophical work written by Plato in the early-middle 4th century BCE that investigates the definitions of knowledge, nature of knowledge, and is considered one of the founding works of epistemology. Like many of Plato's works, the ''Theaetetus'' is written in the form of a Socratic dialogue, dialogue, in this case between Socrates and the young mathematician Theaetetus (mathematician), Theaetetus and his teacher Theodorus of Cyrene. In the dialogue, Socrates and Theaetetus attempt to come up with a definition of ''episteme'', or knowledge, and discuss three definitions of knowledge: knowledge as nothing but ''perception'', knowledge as ''true judgment'', and, finally, knowledge as a ''Belief#Justified true belief, true judgment with an account.'' Each of these definitions is shown to be unsatisfactory as the dialogue ends in aporia as Socrates leaves to face a hearing for his trial for ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cratylus (dialogue)

''Cratylus'' ( ; , ) is the name of a dialogue by Plato. Most modern scholars agree that it was written mostly during Plato's so-called middle period. In the dialogue, Socrates is asked by two men, Cratylus and Hermogenes (philosopher), Hermogenes, to tell them whether names are "conventional" or "natural", that is, whether language is a system of arbitrary signs or whether words have an intrinsic relation to the things they signify. The individual Cratylus was the first intellectual influence on Plato. Aristotle states that Cratylus influenced Plato by introducing to him the teachings of Heraclitus, according to M. W. Riley. Summary The subject of Cratylus is ''on'' ''the correctness of names'' (), in other words, it is a critique on the subject of naming (Baxter). When discussing an (''Wikt:áœÎœÎżÎŒÎ±, onoma'') and how it would relate to its subject, Socrates compares the original creation of a word to the work of an artist. An artist uses color to express the essence of hi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Phaedo

''Phaedo'' (; , ''PhaidĆn'') is a dialogue written by Plato, in which Socrates discusses the immortality of the soul and the nature of the afterlife with his friends in the hours leading up to his death. Socrates explores various arguments for the soul's immortality with the Pythagorean philosophers Simmias and Cebes of Thebes in order to show that there is an afterlife in which the soul will dwell following death. The dialogue concludes with a mythological narrative of the descent into Tarturus and an account of Socrates' final moments before his execution. Background The dialogue is set in 399 BCE, in an Athenian prison, during the last hours prior to the death of Socrates. It is presented within a frame story by Phaedo of Elis, who is recounting the events to Echecrates, a Pythagorean philosopher. Characters Speakers in the frame story: * Phaedo of Elis: a follower of Socrates, a youth allegedly enslaved as a prisoner of war, whose freedom was purchased at Soc ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Crito

''Crito'' ( or ; ) is a dialogue written by the ancient Greece, ancient Greek philosopher Plato. It depicts a conversation between Socrates and his wealthy friend Crito of Alopece regarding justice (''ÎŽÎčÎșαÎčÎżÏÏΜη''), injustice (''áŒÎŽÎčÎșία''), and the appropriate response to injustice. It follows Socrates' imprisonment, just after the events of the ''Apology (Plato), Apology''. In ''Crito'', Socrates believes injustice may not be answered with injustice, personifies the Laws of Athens to prove this, and refuses Crito's offer to finance his escape from prison. The dialogue contains an ancient statement of the social contract theory of government. In contemporary discussions, the meaning of ''Crito'' is debated to determine whether it is a plea for unconditional obedience to the laws of a society. The text is one of the few Platonic dialogues that appear to be unaffected by Plato's opinions on the matter; it is dated to have been written around the same time as the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Apologia Sokratous

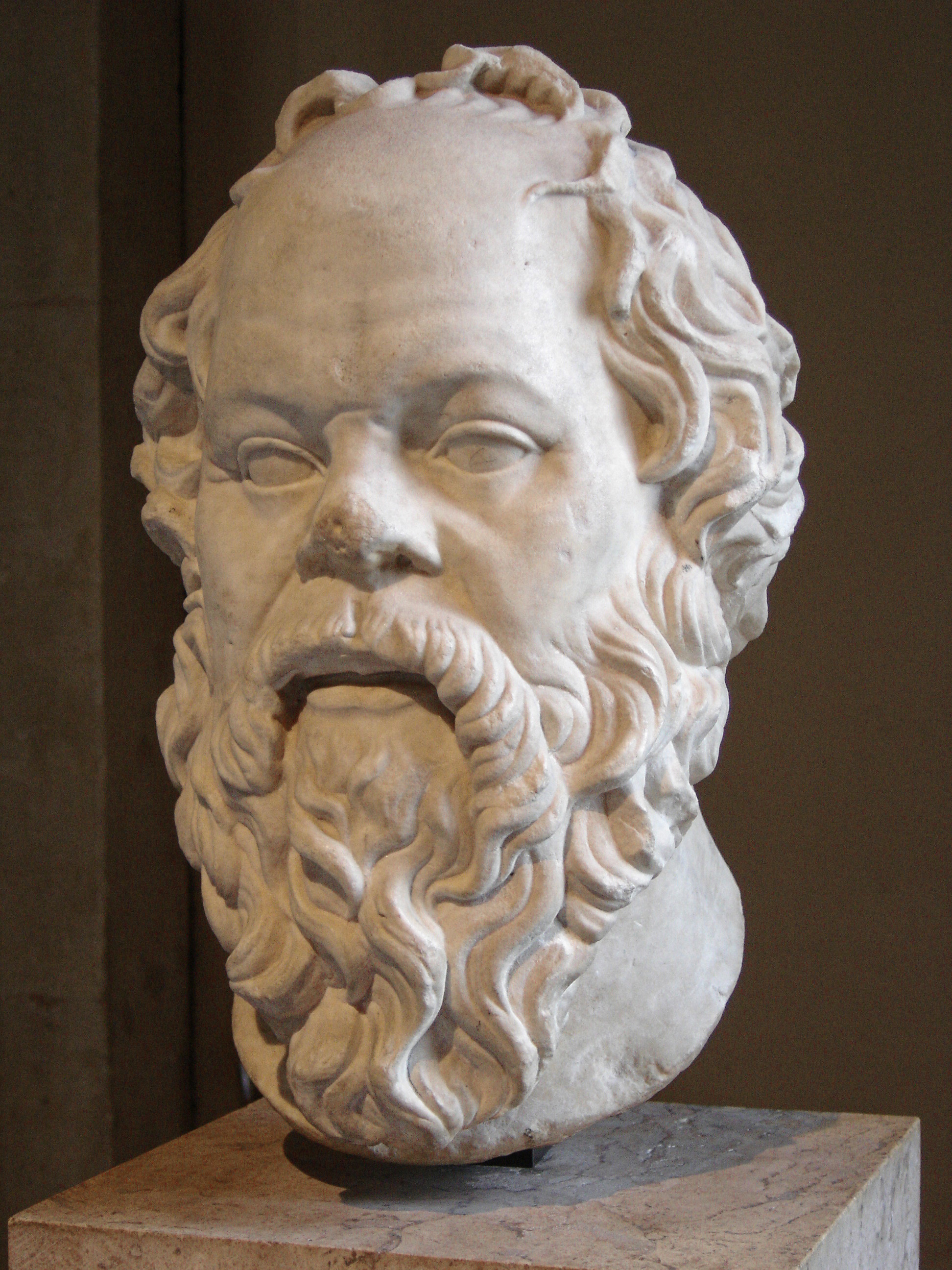

The ''Apology of Socrates'' (, ''ApologĂa SokrĂĄtous''; ), written by Plato, is a Socratic dialogue of the speech of legal self-defence which Socrates (469â399 BC) spoke at his trial for impiety and corruption in 399 BC. Specifically, the ''Apology of Socrates'' is a defence against the charges of "corrupting the youth" and " not believing in the gods in whom the city believes, but in other '' daimonia'' that are novel" to Athens (24b). Among the primary sources about the trial and death of the philosopher Socrates, the ''Apology of Socrates'' is the dialogue that depicts the trial, and is one of four Socratic dialogues, along with ''Euthyphro'', ''Phaedo'', and ''Crito'', through which Plato details the final days of the philosopher Socrates. There are debates among scholars as to whether we should rely on the ''Apology'' for information about the trial itself. The text of ''Apology'' The ''Apology of Socrates'', by the philosopher Plato (429â347 BC), was one of man ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Euthyphro

''Euthyphro'' (; ), is a philosophical work by Plato written in the form of a Socratic dialogue set during the weeks before the trial of Socrates in 399 BC. In the dialogue, Socrates and Euthyphro attempt to establish a definition of '' piety''. This however leads to the main dilemma of the dialogue when the two cannot come to a satisfactory conclusion. Is something pious because the gods approve of it? Or do the gods approve of it because it is pious? This aporetic ending has led to one of the longest theological and meta-ethical debates in history. Characters *Socrates Socrates (; ; â 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ..., the Athenian philosopher, currently waiting at the Porch of the King Archon to attend a preliminary hearing for his trial for impiety. He questions the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Oxford Classical Texts

Oxford Classical Texts (OCT), or Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis, is a series of books published by Oxford University Press. It contains texts of ancient Greek and Latin literature, such as Homer's ''Odyssey'' and Virgil's ''Aeneid'', in the original language with a critical apparatus. Works of science and mathematics, such as Euclid's '' Elements'', are generally not represented. Since the books are meant primarily for serious students of the classics, the prefaces and notes have traditionally been in Latin (so that the books are written in the classical languages from the title page to the index), and no translations or explanatory notes are included. Several recent volumes, beginning with Lloyd-Jones and Wilson's 1990 edition of Sophocles, have broken with tradition and feature introductions written in English (though the critical apparatus is still in Latin). In format, Oxford Classical Texts have always been published in British Crown octavo (7œ by 5Œ inches) ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |