|

Merozoite Surface Protein

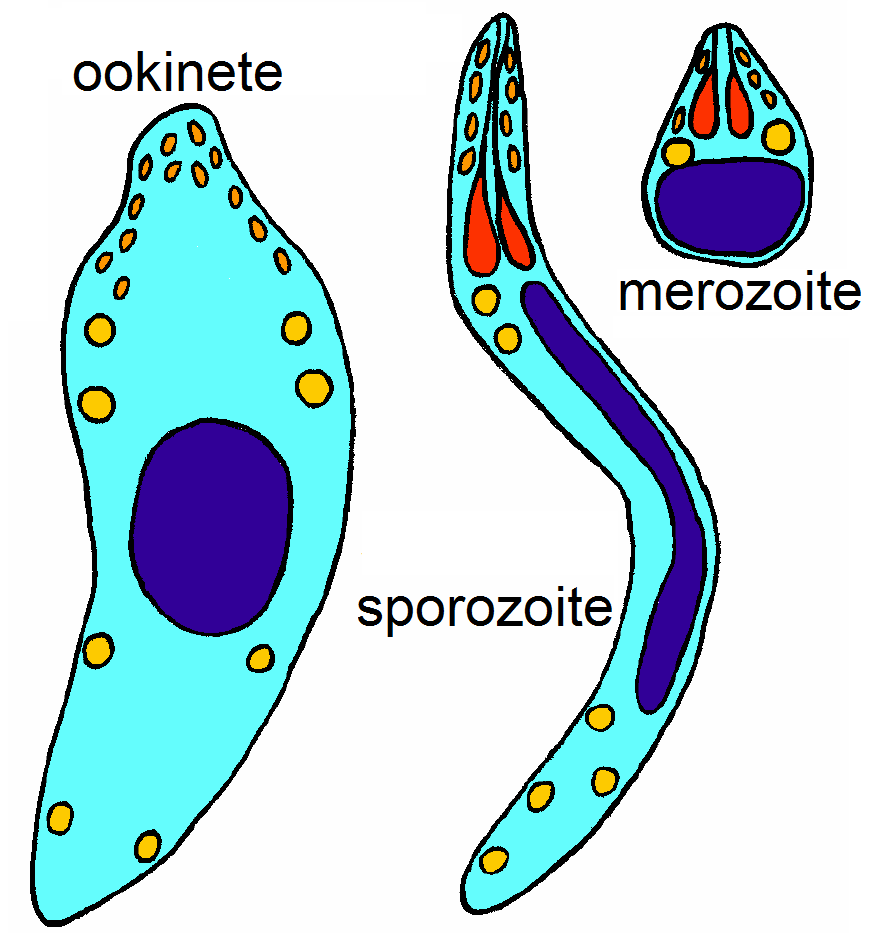

Merozoite surface proteins are both integral and peripheral membrane proteins found on the surface of a merozoite, an early life cycle stage of a protozoan. Merozoite surface proteins, or MSPs, are important in understanding malaria, a disease caused by protozoans of the genus Plasmodium. During the asexual blood stage of its life cycle, the malaria parasite enters red blood cells to replicate itself, causing the classic symptoms of malaria. These surface protein complexes are involved in many interactions of the parasite with red blood cells and are therefore an important topic of study for scientists aiming to combat malaria. Forms The most common form of MSPs are anchored to the merozoite surface with glycophosphatidylinositol, a short glycolipid often used for protein anchoring. Additional forms include integral membrane proteins and peripherally associated proteins, which are found to a lesser extent than glycophosphatidylinositol anchored proteins, or (GPI)-anchored protein ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, responding to stimuli, providing structure to cells and organisms, and transporting molecules from one location to another. Proteins differ from one another primarily in their sequence of amino acids, which is dictated by the nucleotide sequence of their genes, and which usually results in protein folding into a specific 3D structure that determines its activity. A linear chain of amino acid residues is called a polypeptide. A protein contains at least one long polypeptide. Short polypeptides, containing less than 20–30 residues, are rarely considered to be proteins and are commonly called peptides. The individual amino acid residues are bonded together by peptide bonds and adjacent amino acid residues. The sequence of amino acid resid ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Food Vacuole

The food vacuole, or digestive vacuole, is an organelle found in simple eukaryotes such as protists. This organelle is essentially a lysosome. During the stage of the symbiont parasites' lifecycle where it resides within a human (or other mammalian) red blood cell, it is the site of haemoglobin digestion and the formation of the large haemozoin crystals that can be seen under a light microscope. See also * Protists * Eukaryote * Amoeba * Lysosome * Enzymes * Euglenid Euglenids (euglenoids, or euglenophytes, formally Euglenida/Euglenoida, ICZN, or Euglenophyceae, ICBN) are one of the best-known groups of flagellates, which are excavate eukaryotes of the phylum Euglenophyta and their cell structure is typical ...s * Paramecia References Malaria {{Eukaryote-stub ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Parasitology

Parasitology is the study of parasites, their hosts, and the relationship between them. As a biological discipline, the scope of parasitology is not determined by the organism or environment in question but by their way of life. This means it forms a synthesis of other disciplines, and draws on techniques from fields such as cell biology, bioinformatics, biochemistry, molecular biology, immunology, genetics, evolution and ecology. Fields The study of these diverse organisms means that the subject is often broken up into simpler, more focused units, which use common techniques, even if they are not studying the same organisms or diseases. Much research in parasitology falls somewhere between two or more of these definitions. In general, the study of prokaryotes falls under the field of bacteriology rather than parasitology. Medical The parasitologist F.E.G. Cox noted that "Humans are hosts to nearly 300 species of parasitic worms and over 70 species of protozoa, some derived ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution. ::"The chromosomal or genomic location of a gene or any other genetic element is called a locus (plural: loci) and alternative DNA sequences at a locus are called alleles." The simplest alleles are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP). but they can also be insertions and deletions of up to several thousand base pairs. Popular definitions of 'allele' typically refer only to different alleles within genes. For example, the ABO blood grouping is controlled by the ABO gene, which has six common alleles (variants). In population genetics, nearly every living human's phenotype for the ABO gene is some combination of just these six alleles. Most alleles observed result in little or no change in the function of the gene product it codes for. However, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. The term ''antigen'' originally referred to a substance that is an antibody generator. Antigens can be proteins, peptides (amino acid chains), polysaccharides (chains of monosaccharides/simple sugars), lipids, or nucleic acids. Antigens are recognized by antigen receptors, including antibodies and T-cell receptors. Diverse antigen receptors are made by cells of the immune system so that each cell has a specificity for a single antigen. Upon exposure to an antigen, only the lymphocytes that recognize that antigen are activated and expanded, a process known as clonal selection. In most cases, an antibody can only react to and bind one specific antigen; in some instances, however, antibodies may cross-reactivity, cross-react and bind more tha ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Suramin

Suramin is a medication used to treat African sleeping sickness and river blindness. It is the treatment of choice for sleeping sickness without central nervous system involvement. It is given by injection into a vein. Suramin causes a fair number of side effects. Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, skin tingling, and weakness. Sore palms of the hands and soles of the feet, trouble seeing, fever, and abdominal pain may also occur. Severe side effects may include low blood pressure, decreased level of consciousness, kidney problems, and low blood cell levels. It is unclear if it is safe when breastfeeding. Suramin was made at least as early as 1916. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. In the United States it can be acquired from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). In regions of the world where the disease is common suramin is provided for free by the World Health Organization (WHO). Medical uses Suramin ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Erythrocytic

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "hollow vessel", with ''-cyte'' translated as "cell" in modern usage), are the most common type of blood cell and the vertebrate's principal means of delivering oxygen (O2) to the body tissues—via blood flow through the circulatory system. RBCs take up oxygen in the lungs, or in fish the gills, and release it into tissues while squeezing through the body's capillaries. The cytoplasm of a red blood cell is rich in hemoglobin, an iron-containing biomolecule that can bind oxygen and is responsible for the red color of the cells and the blood. Each human red blood cell contains approximately 270 million hemoglobin molecules. The cell membrane is composed of proteins and lipids, and this structure provides properties essential fo ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Vaccine

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe, its toxins, or one of its surface proteins. The agent stimulates the body's to recognize the agent as a threat, destroy it, and to further recognize and destroy any of the microorganisms associated with that agent that it may encounter in the future. Vaccines can be prophylactic (to pr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Merozoite Surface Protein-1 Segments From Sequence Processing

Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organism is typified by a ''cellular variety'' with a distinct morphology and biochemistry. Not all apicomplexa develop all the following cellular varieties and division methods. This presentation is intended as an outline of a hypothetical generalised apicomplexan organism. Methods of asexual replication Apicomplexans (sporozoans) replicate via ways of multiple fission (also known as schizogony). These ways include , and , although the latter is sometimes referred to as schizogony, despite its general meaning. Merogony is an asexually reproductive process of apicomplexa. After infecting a host cell, a trophozoite ( see glossary below) increases in size while repeatedly replicating its nucleus and other organelles. During this process, the orga ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

C-terminus

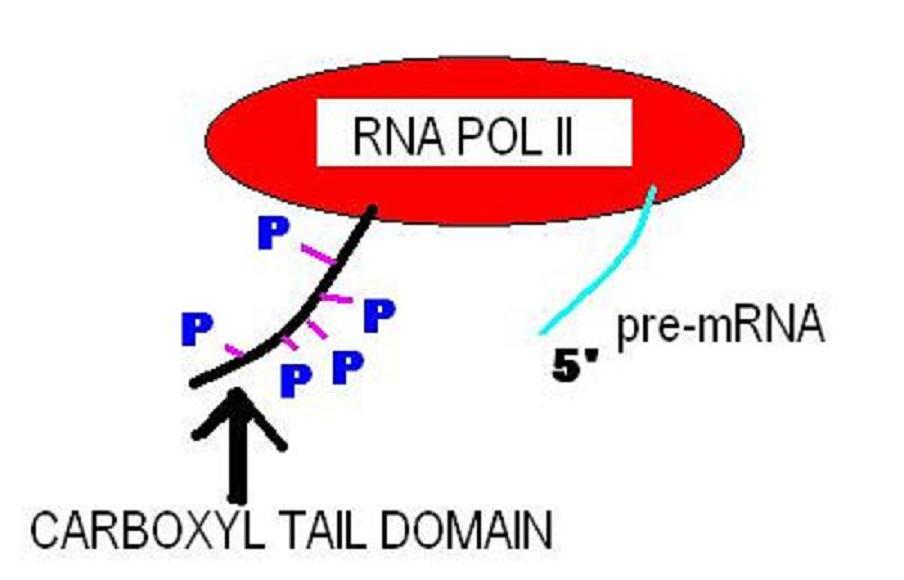

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When the protein is translated from messenger RNA, it is created from N-terminus to C-terminus. The convention for writing peptide sequences is to put the C-terminal end on the right and write the sequence from N- to C-terminus. Chemistry Each amino acid has a carboxyl group and an amine group. Amino acids link to one another to form a chain by a dehydration reaction which joins the amine group of one amino acid to the carboxyl group of the next. Thus polypeptide chains have an end with an unbound carboxyl group, the C-terminus, and an end with an unbound amine group, the N-terminus. Proteins are naturally synthesized starting from the N-terminus and ending at the C-terminus. Function C-terminal retention signals While the N-terminus of a protein often co ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Merozoite

Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organism is typified by a ''cellular variety'' with a distinct morphology and biochemistry. Not all apicomplexa develop all the following cellular varieties and division methods. This presentation is intended as an outline of a hypothetical generalised apicomplexan organism. Methods of asexual replication Apicomplexans (sporozoans) replicate via ways of multiple fission (also known as schizogony). These ways include , and , although the latter is sometimes referred to as schizogony, despite its general meaning. Merogony is an asexually reproductive process of apicomplexa. After infecting a host cell, a trophozoite ( see glossary below) increases in size while repeatedly replicating its nucleus and other organelles. During this process, the orga ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Spectrin

Spectrin is a cytoskeletal protein that lines the intracellular side of the plasma membrane in eukaryotic cells. Spectrin forms pentagonal or hexagonal arrangements, forming a scaffold and playing an important role in maintenance of plasma membrane integrity and cytoskeletal structure. The hexagonal arrangements are formed by tetramers of spectrin subunits associating with short actin filaments at either end of the tetramer. These short actin filaments act as junctional complexes allowing the formation of the hexagonal mesh. The protein is named spectrin since it was first isolated as a major protein component of human red blood cells which had been treated with mild detergents; the detergents lysed the cells and the hemoglobin and other cytoplasmic components were washed out. In the light microscope the basic shape of the red blood cell could still be seen as the spectrin-containing submembranous cytoskeleton preserved the shape of the cell in outline. This became known as a re ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |