|

Guangxitoxin

Guangxitoxin, also known as GxTX, is a peptide toxin found in the venom of the tarantula '' Plesiophrictus guangxiensis''. It primarily inhibits outward voltage-gated Kv2.1 potassium channel currents, which are prominently expressed in pancreatic β-cells, thus increasing insulin secretion. Sources Guangxitoxin is found in the venom of the tarantula '' Plesiophrictus guangxiensis'', which lives mainly in Guangxi province of southern China. Chemistry Subtypes Guangxitoxin consists of multiple subtypes, including GxTX-1D, GxTX-1E and GxTX-2. GxTX-2 shows sequence similarities with Hanatoxin (HaTX), Stromatoxin-1 (ScTx1), and ''Scodra griseipes'' toxin (SGTx) peptides. GxTX-1 shows sequence similarities with Jingzhaotoxin-III (JZTX-III), ''Grammostola spatulata'' mechanotoxin-4 (GsMTx-4), and Voltage-sensor toxin-1 (VSTX1) peptides. GxTX-1 consists of two variants, GxTX-1D and GxTX-1E, of which GxTX-1E is a more potent inhibitor of Kv2.1. Sequence GxTX-1D and GxTX-1E consist of ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tarantula

Tarantulas comprise a group of large and often hairy spiders of the family Theraphosidae. , 1,100 species have been identified, with 166 genera. The term "tarantula" is usually used to describe members of the family Theraphosidae, although many other members of the same infraorder ( Mygalomorphae) are commonly referred to as "tarantulas" or "false tarantulas". Some of the more common species have become popular in the exotic pet trade. Many New World species kept as pets have setae known as urticating hairs that can cause irritation to the skin, and in extreme cases, cause damage to the eyes. Overview Like all arthropods, the tarantula is an invertebrate that relies on an exoskeleton for muscular support.Pomeroy, R. (2014, February 4). Pub. Real Clear Science, "Spiders, and Their Amazing Hydraulic Legs and Genitalia". Retrieved October 13, 2019, from https://www.realclearscience.com/blog/2013/02/spiders-their-amazing-hydraulic-legs-and-genitals.html. Like other Arachni ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

KCNB1

Potassium voltage-gated channel, Shab-related subfamily, member 1, also known as KCNB1 or Kv2.1, is a protein that, in humans, is encoded by the ''KCNB1'' gene. Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily B member one, or simply known as KCNB1, is a delayed rectifier and voltage-gated potassium channel found throughout the body. The channel has a diverse number of functions. However, its main function, as a delayed rectifier, is to propagate current in its respective location. It is commonly expressed in the central nervous system, but may also be found in pulmonary arteries, auditory outer hair cells, stem cells, the retina, and organs such as the heart and pancreas. Modulation of K+ channel activity and expression has been found to be at the crux of many profound pathophysiological disorders in several cell types. Potassium channels are among the most diverse of all ion channels in eukaryotes. With over 100 genes coding numerous functions, many isoforms of potassium channels are ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Beta Cell

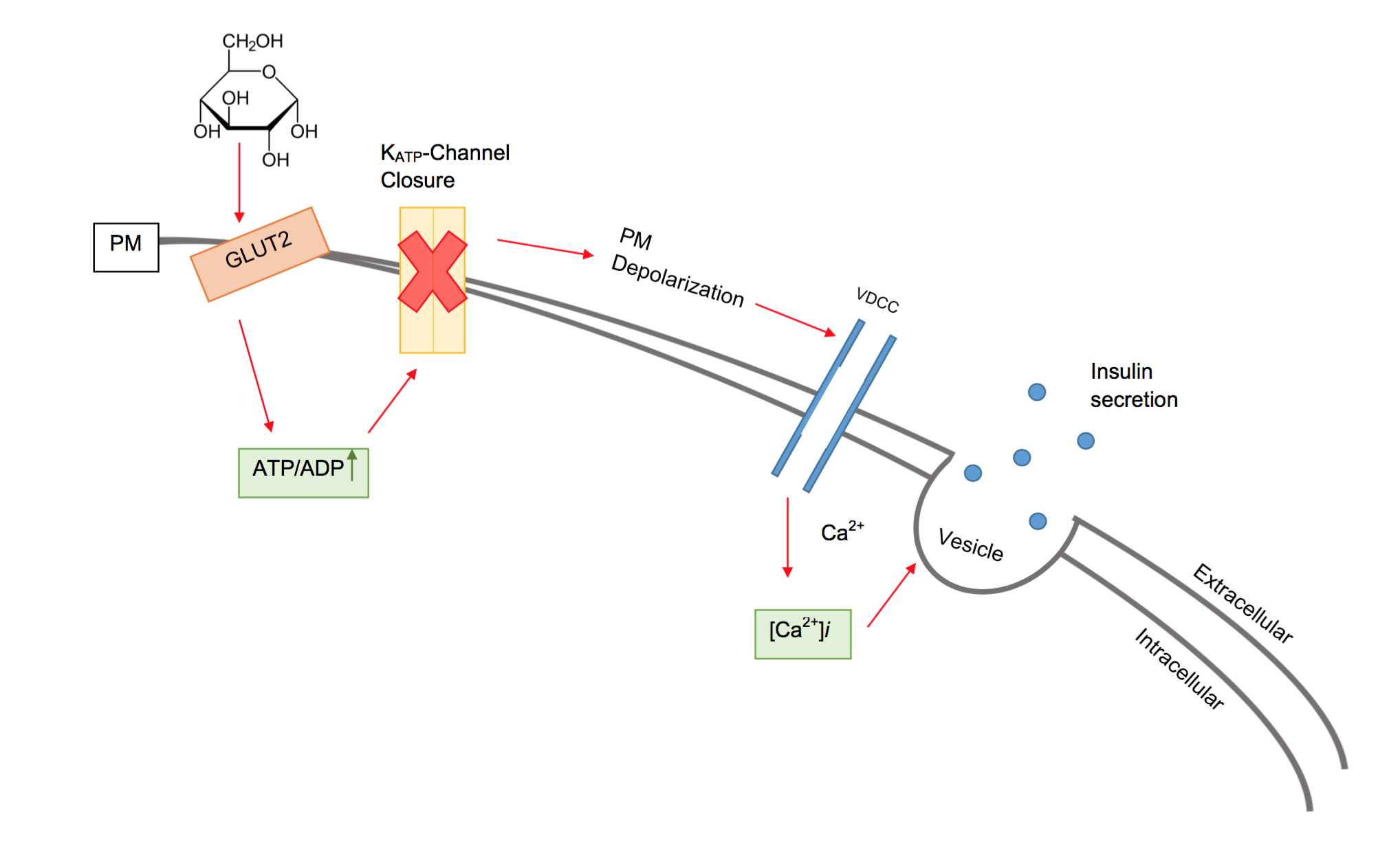

Beta cells (β-cells) are specialized endocrine cells located within the pancreatic islets of Langerhans responsible for the production and release of insulin and amylin. Constituting ~50–70% of cells in human islets, beta cells play a vital role in maintaining blood glucose levels. Problems with beta cells can lead to disorders such as diabetes. Function The function of beta cells is primarily centered around the synthesis and secretion of hormones, particularly insulin and amylin. Both hormones work to keep blood glucose levels within a narrow, healthy range by different mechanisms. Insulin facilitates the uptake of glucose by cells, allowing them to use it for energy or store it for future use. Amylin helps regulate the rate at which glucose enters the bloodstream after a meal, slowing down the absorption of nutrients by inhibit gastric emptying. Insulin synthesis Beta cells are the only site of insulin synthesis in mammals. As glucose stimulates insulin secretion, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Inhibitor Cystine Knot

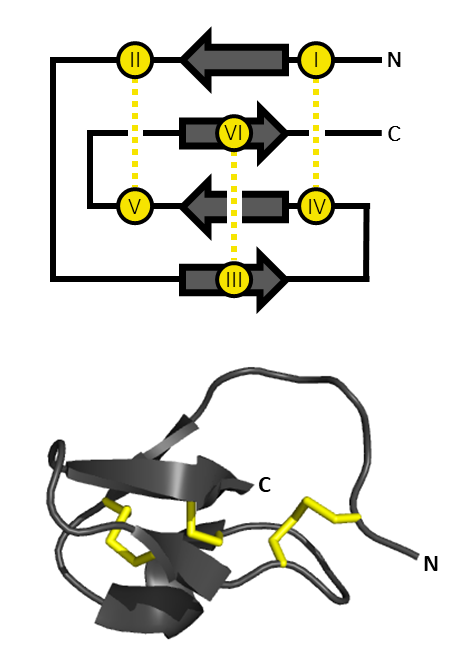

An inhibitor cystine knot (also known as ICK or Knottin) is a protein structural motif containing three disulfide bridges. Knottins are one of three folds in the cystine knot motif; the other closely related knots are the growth factor cystine knot (GFCK) and the cyclic cystine knot (CCK; cyclotide). Types include a) cyclic mobius, b) cyclic bracelet, c) acyclic inhibitor knottins. Cystine knot motifs are found frequently in nature in a plethora of plants, animals, and fungi and serve diverse functions from appetite suppression to anti-fungal activity. Along with the sections of polypeptide between them, two disulfides form a loop through which the third disulfide bond (linking the 3rd and 6th cysteine in the sequence) passes, forming a knot. The motif is common in invertebrate toxins such as those from arachnids and molluscs. The motif is also found in some inhibitor proteins found in plants, but the plant and animal motifs are thought to be a product of convergent evolution. Th ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Jingzhaotoxin

Jingzhaotoxin proteins are part of a venom secreted by '' Chilobrachys jingzhao'', the Chinese tarantula. and act as neurotoxins. There are several subtypes of jingzhaotoxin, which differ in terms of channel selectivity and modification characteristics. All subspecies act as gating modifiers of sodium channels and/or, to a lesser extent, potassium channels. Sources ''Chilobrachys jingzhao'', also known as the Chinese earth tiger tarantula or ''Chilobrachys guangxiensis'', can be found in China and Asia. This large tarantula belongs to the family of Theraphosidae.Taxonomy Chilobrachys Jingzhao Chemistry Jingzhaotoxins reported on this page are 29-36-residue polypeptides with varying numbers of stabilizing disulfide bridges.Liao, Z., Cao, J., Li, S., Yan, X., Hu, W., He, Q., Chen, J., Tang, J., Xie, J., & Liang, S. (2007). Proteomic and peptidomic analysis of the venom from Chinese tarantula Chilobrachys jingzhao. ''Proteomics, 7'', 1892-1907.Chen, J., Zhang, Y., Rong, M., Zhao, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Plesiophrictus Guangxiensis

''Plesiophrictus'' is a genus of tarantulas that was first described by Reginald Innes Pocock in 1899. Species it contains eight species, found in Sri Lanka, India, and Micronesia: *'' Plesiophrictus fabrei'' (Simon, 1892) – India *'' Plesiophrictus linteatus'' (Simon, 1891) – India *''Plesiophrictus meghalayaensis'' Tikader, 1977 – India *''Plesiophrictus millardi'' Pocock, 1899 (type) – India *''Plesiophrictus nilagiriensis'' Siliwal, Molur & Raven, 2007 – India *''Plesiophrictus senffti'' (Strand, 1907) – Micronesia *''Plesiophrictus sericeus'' Pocock, 1900 – India *''Plesiophrictus tenuipes'' Pocock, 1899 – Sri Lanka Formerly included: *''P. bhori'' Gravely, 1915 (Transferred to ''Heterophrictus'') *''P. blatteri'' Gravely, 1935 (Transferred to ''Heterophrictus'') *''P. collinus'' Pocock, 1899 (Transferred to ''Sahydroaraneus'') *''P. guangxiensis'' Yin & Tan, 2000 (Transferred to ''Chilobrachys'') *''P. madraspatanus'' Gravely, 1935 (Transferred to ''Neohete ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Disulfide Bonds

In chemistry, a disulfide (or disulphide in British English) is a compound containing a functional group or the anion. The linkage is also called an SS-bond or sometimes a disulfide bridge and usually derived from two thiol groups. In inorganic chemistry, the anion appears in a few rare minerals, but the functional group has tremendous importance in biochemistry. Disulfide bridges formed between thiol groups in two cysteine residues are an important component of the tertiary and quaternary structure of proteins. Compounds of the form are usually called '' persulfides'' instead. Organic disulfides Structure Disulfides have a C–S–S–C dihedral angle approaching 90°. The S–S bond length is 2.03 Å in diphenyl disulfide, similar to that in elemental sulfur. Disulfides are usually symmetric but they can also be unsymmetric. Symmetrical disulfides are compounds of the formula . Most disulfides encountered in organosulfur chemistry are symmetrical disulfides. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Hydrophobe

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the chemical property of a molecule (called a hydrophobe) that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water. In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water. Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, thus, prefer other neutral molecules and nonpolar solvents. Because water molecules are polar, hydrophobes do not dissolve well among them. Hydrophobic molecules in water often cluster together, forming micelles. Water on hydrophobic surfaces will exhibit a high contact angle. Examples of hydrophobic molecules include the alkanes, oils, fats, and greasy substances in general. Hydrophobic materials are used for oil removal from water, the management of oil spills, and chemical separation processes to remove non-polar substances from polar compounds. The term ''hydrophobic''—which comes from the Ancient Greek (), "having a fear of water", constructed Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Acidic

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis acid. The first category of acids are the proton donors, or Brønsted–Lowry acids. In the special case of aqueous solutions, proton donors form the hydronium ion H3O+ and are known as Arrhenius acids. Brønsted and Lowry generalized the Arrhenius theory to include non-aqueous solvents. A Brønsted–Lowry or Arrhenius acid usually contains a hydrogen atom bonded to a chemical structure that is still energetically favorable after loss of H+. Aqueous Arrhenius acids have characteristic properties that provide a practical description of an acid. Acids form aqueous solutions with a sour taste, can turn blue litmus red, and react with bases and certain metals (like calcium) to form salts. The word ''acid'' is derived from the Latin , meaning 'sour'. An aqueous solution of an ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Base (chemistry)

In chemistry, there are three definitions in common use of the word "base": '' Arrhenius bases'', '' Brønsted bases'', and '' Lewis bases''. All definitions agree that bases are substances that react with acid An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...s, as originally proposed by Guillaume-François Rouelle, G.-F. Rouelle in the mid-18th century. In 1884, Svante Arrhenius proposed that a base is a substance which dissociates in aqueous solution to form hydroxide ions OH−. These ions can react with Hydron (chemistry), hydrogen ions (H+ according to Arrhenius) from the dissociation of acids to form water in an acid–base reaction. A base was therefore a metal hydroxide such as NaOH or Calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)2. Such aqueous hydroxide solutions were also described by ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Protein Domain

In molecular biology, a protein domain is a region of a protein's Peptide, polypeptide chain that is self-stabilizing and that Protein folding, folds independently from the rest. Each domain forms a compact folded Protein tertiary structure, three-dimensional structure. Many proteins consist of several domains, and a domain may appear in a variety of different proteins. Molecular evolution uses domains as building blocks and these may be recombined in different arrangements to create proteins with different functions. In general, domains vary in length from between about 50 amino acids up to 250 amino acids in length. The shortest domains, such as zinc fingers, are stabilized by metal ions or Disulfide bond, disulfide bridges. Domains often form functional units, such as the calcium-binding EF-hand, EF hand domain of calmodulin. Because they are independently stable, domains can be "swapped" by genetic engineering between one protein and another to make chimera (protein), chimeric ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Lipid Membranes

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many viruses are made of a lipid bilayer, as are the nuclear membrane surrounding the cell nucleus, and membranes of the membrane-bound organelles in the cell. The lipid bilayer is the barrier that keeps ions, proteins and other molecules where they are needed and prevents them from diffusing into areas where they should not be. Lipid bilayers are ideally suited to this role, even though they are only a few nanometers in width, because they are impermeable to most water-soluble (hydrophilic) molecules. Bilayers are particularly impermeable to ions, which allows cells to regulate salt concentrations and pH by transporting ions across their membranes using proteins called ion pumps. Biological bilayers are usually composed of amphiphilic phospholipids that have a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |